#she also pirated Computer drawing and drawn with a mouse for a while before saving up for a drawing tablet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

💫👁️👁️

I'm still figuring Estelle out but Estelle is the type of person to try out different hobbies for a short time before sticking to Games on her MacBook, and printing flowers in her small collection of books is one of them

#oc shit#i know for a fact she read manga during her middle school and highschool era#she also pirated Computer drawing and drawn with a mouse for a while before saving up for a drawing tablet#****computer drawing software

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Introduction to Gothic Games

In this short essay, we’re going to take a layperson’s look at Gothic video games, how they draw on their literary predecessors, and what they offer to the genre that no other medium has managed.

The components of the gothic tale are at this point well-worn tropes in literature, comfortable to slip into and easy to digest. Gothic iconography – the mouldering manor, the decayed bloodline, the horrific creature – has become the symbol of mass-market consumerism, cropping up every October to implore us to purchase candy and decorations. Draculas and Frankenstein’s Monsters grin out from cereal boxes, while zombies creep their way out of film-screens and into works of literature where they did not originally exist, such as in Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009). It should be no surprise that the largest grossing entertainment industry in the United States, the video game industry, also shares this preoccupation with the Gothic. Even before it ballooned to the size it is today, some of the earliest games were based upon the generic moves and tropes originated in gothic novels. In this paper, I will provide a brief overview of the history of “horror games” before examining several titles classified as such in the popular imagination, drawing from a broad range of years and developers, in order to comment on how some of the most popular titles utilize the conventions of the Gothic to produce works of interactive media.

The immediate and obvious difference between Gothic novels and games is the interactive nature of the latter, which faces the challenge of interface. This problem is not unique to the “horror” game genre – and throughout this paper I refer to games alternately as “horror” or “Gothic” interchangeably – but it has been handled differently from the vast majority of other genres by developers. When developing a video game, the primary goal of the developer, when designing the physical control scheme that one uses to play the game (be it mouse, keyboard, controller or other input) is to remove, as much as possible, any sense of friction between the player executing a command and their onscreen avatar carrying it out. This is primarily due to the fact that most modern video games are power fantasies – the player-character is the best soldier in the world, or a superhero, or a powerful wizard. Any time the player feels hindered in their control, it creates a psychological dissonance that disconnects him or her from the state of play and causes frustration. Over decades, a series of best practices has emerged so that, within a genre, designers understand what the easiest and most intuitive control schemes are. For horror games, however, this is less true, because unlike most other game genres, horror games are not empowerment fantasies. The protagonist of a horror game is often pursued by monsters, lost and confused, deprived of resources and subjected to all sorts of physical and psychological trauma from which they will be lucky to escape alive. As a result, many styles of control that have become obsolete over the years persist in horror. The most famous example of this creative choice are so-called “tank controls,” which feature as the control method for the first three case studies presented below. Tank controls are a form of avatar locomotion where, appropriately, the player-character controls like a tank: in order to change direction, the character must pivot in place to face the direction of intended movement before being able to step forward. The camera is static, and does not follow the player. This is in contrast to games where the player may press a directional input and their avatar will immediately move without first having to go through a pivoting process, and the camera dynamically changes angles to always be behind the avatar. The original reason for the tank control implementation was due to technological deficits: early three-dimensional environments utilized pre-rendered images generated on powerful computers that could be drawn to the screen on a lower-powered game console as static backgrounds. Because these backgrounds were, in essence, flat photographs, the camera could not move around without exposing the artifice of the game’s environment and breaking the illusion. As technology advanced and the ability to freely move the camera in a three-dimensional environment became standard, many horror game developers felt that despite their outdated design, the frustration of having to grapple with unintuitive controls increases the tension felt by a player, heightening their sense of stress and fear in hairy moments. Robin Hunicke’s MDA Framework[1] posits that games can be viewed through a triumvirate set of lenses that work together to create a unified experience: “the mechanics give rise to dynamic system behavior, which in turn leads to particular aesthetic experiences. From the player ís perspective, aesthetics set the tone, which is born out in observable dynamics and eventually, operable mechanics” (emphasis mine.) Interestingly, artificially restricting the player-character’s movement straddles all three categories. It is one thing to run from a monster, but it is quite another to do so with one’s metaphorical legs tied together. It is in the horror game genre that one of the golden rules of interactive design can be found suspended with frequency, acting as an exception that proves the rule: it is not always better to provide a frictionless control experience to players.

Example screen of Haunted House

The horror game genre began in earnest the 1980s, with an increasingly-rapid number of releases designed to scare players. One of the earliest of these titles is Haunted House (1981) for the Atari 2600. As will become apparent, the traditional Gothic locale of the haunted house was immediately seen as an attractive setting for staging a game, and the play of Haunted House involved attempting to escape from the titular house while avoid monsters like bats and ghosts – though the visuals were so primitive that it was unlikely any player would truly feel their spine tingling. A series of haunted house games followed, however, such as Terror House(1982, Bandai LCD Solar) and Ghost House (1986, SEGA Master System), while other horror titles looked directly to classic works of gothic literature for inspiration, producing games such as Castlevania (1986, Nintendo Entertainment System) and Frankenstein (1987, Commodore 64) adapting or drawing upon Dracula and Frankenstein respectively. While text-based games could do a reasonable job of evoking the sense of dread and foreboding that the Gothic has come to be known for, these were not popular in the marketplace, and most of the best-selling titles were held back by technical limitations. A limited amount of memory restricted the number of colors that could appear onscreen, causing monsters to be rendered as blobs that were difficult to parse or laughably cartoonish. Developers focusing on providing the player with compelling gameplay at the expense of the game’s theme led to titles like Castlevania trading scares for action. It was not until the early 1990s that the power of computers advanced to the point where games could focus on telling a complex narrative of any type through more than simply printing text on the screen – a crucial element in producing a “Gothic” video game.

Carnby explores one of the haunted halls of Derceto

One of the forefathers of the modern horror game is the classic title Alone in the Dark (1992, DOS). The French developer Infogrames drew inspiration from the works of authors such as Edgar Allan Poe and H. P. Lovecraft in producing the title. Set in the year 1920, Alone in the Dark follows in the tradition of earlier haunted house games by trapping the player within the walls of the decaying Louisiana mansion Derceto. Taking on the role of an investigator [2] arriving at the mansion to determine what could have caused the prior owner, artist Jeremy Hartwood, to suddenly decide to take his own life, the player is drawn into intrigue surrounding the death of the mansion’s original owner, pirate Ezechial Pregzt, who was murdered during the civil war and now wishes to return to life to unleash all manner of terrifying beasts upon the unsuspecting world. From the roof of the mansion down into the system of caves below, the investigator must fend off supernatural assaults while working to lay Pregzt’s spirit to rest. The art direction of the game draws upon an aesthetic of romanticism, placing the investigators in an environment that, while not a natural wilderness (save for brief forays outside the manor’s confines,) still conveys via the environmental design a sense of untamed wildness, a darkness that is at once foreboding and irresistible. The manor itself is filled with haunts and ghouls, and the narrative climax, wherein the caverns below the house collapse, is reminiscent of the Fall of the House of Usher, despite the fact that Derceto remains standing for the player to continue exploring following the story’s conclusion, should he or she choose. Alone in the Dark spawned multiple sequels, but its most popular and famous progeny was not one of them. The most successful haunted house game of all time would come not from France but from Japan.

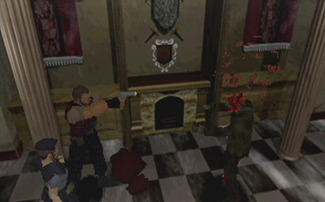

In 1996, Capcom released Resident Evil, known as Bio Hazard in Japan. Doubling down on the horror aspects, Resident Evil, much like Alone in the Dark, allows the player to select from either a male or female protagonist, both operatives with the task force S.T.A.R.S. investigating the disappearance of their fellows at a mysterious abandoned mansion on the outskirts of the Midwest town, Raccoon City. After being harried by dogs that would put the Hound of the Baskervilles to shame, the agents take refuge in the decaying house only to discover that it is infested with zombies. Making their way into the bowels of the mansion, they discover a conspiracy, contend with a traitor in their midst, and ultimately, as all Gothic manors must, the house collapses in on itself. Superficially, it appears that Resident Evil makes many of the same thematic moves as Alone in the Dark, relying on a mansion, supernatural phenomena within it, and a mystery to unravel to build tension. However, there are several factors that account for both this game’s mass-market success and its successful intervention into the Gothic genre. The same graphical improvements that had allowed Alone to stand out from its predecessors had, in the intervening four years, catapulted forward, and Resident Evil’s live-action opening before transitioning into then-cutting edge full three-dimensional explorable environments gave the title a cinematic flair unusual for the era. The second factor was the game’s narrative, unlike Alone in the Dark, grappled with social anxieties in a classic Gothic fashion. Fears over identity and betrayal from within sit alongside more modern tensions such as medical experimentation and government conspiracies.

The protagonists of Resident Evil defeat one of many zombies.

These fears were alive and well not only in the Japanese psyche but worldwide, though within a few months The House of the Dead, another Japanese title involving special agents investigating a mansion full of zombies to uncover a medical conspiracy was blowing up arcades. As has been pointed out, the shift in zombie narratives from supernatural to scientific origin had been underway for some time, and although “it would be a challenge to pinpoint the exact moment,” critics have pointed to Night of the Living Dead, I Am Legend and the research of ethnobotanist Wade Davis for pushing zombies from magic to medicine. [3] The Resident Evil franchise continued into the present, branching out into box-office megahit films while becoming less gothic with each successive title, veering into more of a military fantasy with Resident Evil 4 during the years of the Iraq war when the enemies became infected foreigners, and staying there until 2017’s Resident Evil 7, which took the series back to its roots and harkened back to Alone – the setting is a Faulkneresque dilapidated southern plantation home where the darkness comes not primarily from the undead, but from the family that inhabits its collapsing structure – a redneck version of the Compson family, perhaps, but one that speaks to the class tensions in modern America. Resident Evil’s continual reinvention of itself demonstrates not only the ability of Gothic, as a genre, to take on whatever might be plaguing the collective unconscious of the era, but also how the anxieties of past Gothics – whether foreigners in Dracula or class in Wuthering Heights – return to the modern era wearing new clothing.

The horror game genre fully embraced anxiety and psychological manifestation three years after Resident Evil in the franchise Silent Hill. Expanding the haunted house concept to an entire abandoned town, the city of Silent Hill was notable for having a dual nature: the vaguely unsettling abandoned fog-filled streets would suddenly and without warning transform into an industrial nightmare world of rusting metal beams and horrifying monsters. While the story of a man searching for his lost daughter laid considerable worldbuilding groundwork, it was not until the sequel that the franchise reached its heights. Silent Hill 2 “features a woman’s blanched face on its cover, begins in an isolated, vile public toilet, and is about the spiritual purgatory of a grieving husband.”[4] Protagonist James Sunderland receives a letter from his wife, dead some three years, telling him that she is still alive, and that he must meet her in Silent Hill. When he arrives there, he finds his deepest repressions made manifest on the streets, constantly tormenting him. The environments are filled with hospital beds adorned with crisp white sheets and pillows, the monsters take the form of nurses and even a seemingly-real women he meets appears identical to his wife, despite having a wildly different personality.

James confronts his repressions in a straightforward manner

All the while, Sunderland is stalked by a violent and sexually aggressive creature known as “Pyramid Head.” Furthermore, other people trapped in Silent Hill appear to see the town completely differently – a teenage runaway named Angela, for example, perceives the town as being on fire, whereas Eddie, who has a history of violence, experiences the haunts not as nurses but as people laughing at and taunting him. As the player progresses through the narrative, it slowly becomes apparent that James’ wife did not die from an illness, but was smothered in her hospital bed by none other than James himself in an act that he himself is unsure how to classify – was it an act of mercy, or was it because he had come to resent the burden of caring for her? The trauma and repressed memories James grapples with created the Silent Hill that he experiences, and the murderous Pyramid Head grew out of James’ desire to be punished for his actions, and at the end of the game, with James now fully aware of his mental state, two Pyramid Heads commit suicide in front of him, their function no longer required. This banishment of the monster is a major differentiating factor that separates the gothic horror game from its literary progenitors: “While inhabiting Silent Hill… the challenge is to survive these monsters. Although you can run away from many of them, you cannot escape the boss monsters—you cannot if you wish to carry on your quest and continue to fall into the abyss of the player characters’ tortured souls. Unlike fiction where the question is “whether the creature can be destroyed” (Carroll 1990, 182), the player characters absolutely must destroy them or, for the Pyramid Head(s) of SH2, hold out long enough to make them kill themselves.” [5] The game can end in a variety of ways, ranging from James leaving Silent Hill in peace to following in the steps of Pyramid Head and driving his car into a lake. These variable ending states incentivize players to replay the game, finding different paths through the story in order to try and free James from his demons.

Unlike the Gothic novel, which must end in the way the author has written it, the ability for Gothic games to alter to fit the choices of their players allows designers to drive home psychological horror in a way books may struggle with: the characters descend into their own personal hells by the player’s hand and should they fail to emerge, it is the player’s fault. While readers may be complicit in the reading of a book with an unhappy or particularly traumatic ending, achieving a “bad” ending in a game, especially if a “good” ending is available, doubles the moral burden upon the player – not only are they complicit in acts of abuse against the fictional characters onscreen, but they also failed to guide the narrative to a positive conclusion. Some games, such as Until Dawn (2015) which features teenagers vacationing in cabin in haunted mountains, have made variable endings their main conceit. More of an interactive film than a traditional game, the player is presented with numerous split-second decisions to make with the goal of preserving the lives of every protagonist through the night – it is possible for them all to survive, or for each to meet a grisly death. If any of the protagonists fails to survive, the game drives home the guilt in the ending, as the rest weep about how they were not smart, strong, or fast enough to save their friend(s). Of course, it is the player who is the failure, and has caused the deaths of these teenagers - alongside, of course, the game designer, a puppetmaster who has orchestrated the scenario.

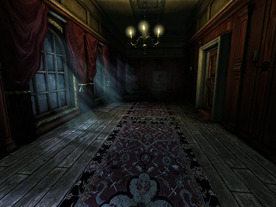

The final case study presented for examination is Amnesia: The Dark Descent (2010). Perhaps the most obviously Gothic of any game herein discussed, Amnesia is set in 1839 and follows the story of the London archeologist Daniel as he finds himself trapped within the walls of Brennenburg Castle in Prussia. Suffering from memory loss and terrorized by the castle’s inhuman inhabitants, Daniel seeks to regain his memories, discover why he inflicted amnesia upon himself, and ultimately escape from Brennenburg. Unlike the games discussed above, Amnesia is played from a first-person perspective instead of a third-person perspective, and more than any other is concerned with the generic convention of a gothic protagonist being disempowered.

Brennenburg’s architecture appears like a modern version of Derceto.

Although it does not feature tank controls, Amnesia’s control scheme still aims to frustrate the player, as all actions must be completed in a realistic fashion. For example, whereas in most games all one needs to do in order to open the door is click on the door, in Amnesia the player must click and hold the mouse cursor on the door handle, then pull the mouse back as if they are pulling on a door. In a similar fashion, cabinets must be opened and closed, cranks must be turned, and drawers must be pulled. The ironic unintuitive nature of this control scheme (it too closely mimics real life physical object interaction for many players, and is considered tedious) causes the player to clumsily fumble with their objectives in tense moments when the game’s monsters are bearing down upon them. The second and perhaps most important way that Amnesia deals with disempowerment is via omission: unlike in any of the prior games discussed, there is no combat. While games such as Resident Evil or Silent Hill often discouraged fighting due to high enemy resiliency and low access to resources such as ammunition or health restoratives, Amnesia prevents combat entirely: if confronted by a monster, the protagonist’s only option is to run and hide, and being caught inevitably leads to a swift demise. Hiding itself is dangerous, however, due to the protagonist’s fear of the dark. If too much time is spent in dark places, the Daniel’s sanity will begin to drop and he will begin to whimper, drawing enemies to his hiding location or resulting in a game over due to going insane. Of course, lighting a match also alerts enemies to Daniel’s presence, so the player is in a constant state of tension, balancing Daniel’s sanity with his physical safety. Furthermore, as Daniel’s sanity drops, he begins to see and hear things that are not real, further confusing the player and making it unclear as to what is a real threat and what is simply an illusion of the mind. Developer Frictional Games’ innovation in showing it was possible to create an environment of Gothic disempowerment via an act of subtraction rather than addition, led to massive critical acclaim and revolutionized the way that horror games were made: both Silent Hills (a now-canceled title) and Resident Evil 7 changed their camera style to a first-person perspective and significantly scaled back their respective combat sequences, the latter even venturing into virtual reality to deliver more immersion and thus deliver more intense scares. Although “survival-horror” existed as a term describing a subgenre within horror games that focused more on stealth and puzzle solving than combat before Amnesia, the subgenre blossomed into its own with the title’s release.

What, then, can be concluded about the gothic genre as it manifests in video games as opposed to books? Obviously, the generalities related to the differing mediums apply – interactivity versus passivity, multimedia versus text, and so forth – but within Gothic specifically, placing horror games next to their literary counterparts reveals the strengths and weaknesses of the form. The kinesthetics of movement tied to play allow games to deliver to modern audiences a visceral feeling of tension more effortlessly than novels, though the written word excels at telling complex narratives that game storytelling still struggles to match. This is to be expected, of course – games are a young medium and the basic tools of signification are not fully understood. Although some would argue that “the best interactive stories are still worse than even middling books and films” and thus “if there is a future of games, let alone a future in which they discover their potential as a defining medium of an era, it will be one in which games abandon the dream of becoming narrative,[6]” horror games show that despite a lack of written narrative complexity to match older media, their ability to deliver narrative experiences on an emotional level – via engagement in an environment, be it solely through the physical manipulation of an onscreen avatar or through total sensory immersion in virtual reality – remains unmatched even at this early date. Gothic games may be the best evidence for this: their focus on the physical input device allows the mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics of a game to work together in a way most other genres do not achieve.

[1] Hunicke, Robin, Marc LeBlanc, Robert Zubek. MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. Game Developer Conference, 2004.

[2] One potential choice for investigator, Edward Carnby, is named for Clark Ashton Smith’s John Carnby, a character found in “Cthulhu Mythos.”

[3] Jones, Tanya Carinae Pell. “From Necromancy to Necrotrophic: Resident Evil’s Influence on the Zombie Origin Shift from Supernatural to Science.” In Unraveling Resident Evil: Essays on the Complex Universe of the Games and Films, ed. Nadine Farghaly. McFarland & Company Publishers, Jefferson: North Carolina. 2014. 19.

[4] Alexander, Leigh. “Why Silent Hill mattered.” Offworld: 1 May 2015 (Web).

[5] Perron, Bernard. Silent Hill: The Terror Engine. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011. 42-43.

[6] Bogost, Ian. “Video Games Are Better Without Stories.” The Atlantic. 25 April 2017.

#red pages podcast news#video games#videogames#horror#game design#indiedev#gamedev#gothic#literature#scary#spooky#amnesia#resident evil#silent hill#until dawn#alone in the dark

0 notes