#sepp dietrich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Documentaries: “The waffen SS were so dangerous, tf you mean⁉️😡😭💦”

The Waffen SS:

“Look grandpa dietrich, a donkey :D”

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sepp Dietrich always gives me grandpa vibes

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nazis with cats day 10: SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer Josef "Sepp" Dietrich with two adorable kittens on his lap.

(The image was taken before his promotion; he is seen here in an SS-Gruppenführer uniform).

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kurt ‘Panzer’ Meyer, Joachim Peiper, and Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich after the war.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A BATALHA DO BULGE - Histórias da Segunda Guerra Mundial - Parte 2

Nota do Autor do Blog: Conforme escrevi no post anterior e é sabido por todos os leitores e estudiosos das batalhas da Segunda Guerra Mundial, a Batalha em questão foi considerada uma das maiores da história, se eu fosse abordá-la aqui por inteiro, seriam necessárias muitas postagens, sugiro aos que se interessaram em saber mais detalhes depois de lerem estas duas partes resumidas que procurem em livros ou na internet pois encontrarão muitas coisas mais para completarem as informações sobre este fato.

ALGUNS ASPECTOS DA BATALHA

Planejamento

O Oberkomando decidiu em meados de setembro, por insistência de Hitler, que a ofensiva seria montada nas Ardenas, como foi feito em 1940. Em 1940, as forças alemãs passaram pelas Ardenas em três dias antes de envolver o inimigo, mas o plano de 1944 pedia a batalha na própria floresta. As principais forças iriam avançar para o oeste no rio Meuse, em seguida, virar para noroeste até Antuérpia e Bruxelas. O terreno próximo das Ardenas dificultaria o movimento rápido, embora o terreno aberto além do Meuse oferecesse a perspectiva de uma corrida bem-sucedida à costa. Quatro exércitos foram selecionados para a operação. Adolf Hitler selecionou pessoalmente para a contra-ofensiva no lado norte da frente ocidental as melhores tropas disponíveis e oficiais em quem confiava. O papel principal no ataque foi dado ao 6º Exército Panzer, comandado pelo SS Oberstgruppenfhrer Sepp Dietrich. Incluía a formação mais experiente da Waffen-SS: a 1ª Divisão Panzer SS Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. Também continha a 12ª Divisão Panzer SS de Hitlerjugend. Eles receberam prioridade para o fornecimento e equipamento e atribuíram a rota mais curta para o objetivo principal da ofensiva, Antuérpia, a partir do ponto mais ao norte na frente de batalha pretendida, mais perto do importante centro da rede rodoviária de Monschau. O Quinto Exército Panzer sob o General Hasso von Manteuffel foi designado para o setor médio com o objetivo de capturar Bruxelas. O Sétimo Exército, sob o General Erich Brandenberger, foi designado para o setor mais meridional, perto da cidade luxemburguesa de Echternach, com a tarefa de proteger o flanco. Este exército era composto de apenas quatro divisões de infantaria, sem formações de armadura em grande escala para usar como uma unidade de ponta de lança. Como resultado, eles fizeram pouco progresso durante a batalha.

Para que a ofensiva fosse bem-sucedida, quatro critérios foram considerados críticos: o ataque teria que ser uma surpresa completa; as condições climáticas tinham que ser pobres para neutralizar a superioridade aérea aliada e os danos que poderia infligir à ofensiva alemã e suas linhas de abastecimento; o progresso tinha que ser rápido - o rio Meuse, a meio caminho de Antuérpia, teria que ser alcançado até o dia 4; e os suprimentos de combustível aliados teriam que ser capturados intactos. O Estado-Maior estimou que eles só tinham combustível suficiente para cobrir um terço da metade do caminho para Antuérpia em condições de combate pesadas.

O abastecimento de combustível alemão era precário – esses materiais e suprimentos que não podiam ser transportados diretamente pela ferrovia, tinham que ser puxados por cavalos para economizar combustível, e as divisões mecanizadas e panzers dependeriam fortemente do combustível capturado. Como resultado, o início da ofensiva foi adiado de 27 de novembro até 16 de dezembro. Antes da ofensiva, os Aliados estavam praticamente cegos para o movimento de tropas alemãs. Durante a libertação da França, a extensa rede da Resistência Francesa tinha fornecido informações valiosas sobre as disposições alemãs. Quando chegaram à fronteira alemã, essa fonte secou. Na França, as ordens foram transmitidas dentro do exército alemão usando mensagens de rádio codificadas pela máquina Enigma, e estas poderiam ser recolhidas e descriptografadas por decifradores de códigos aliados com sede em Bletchley Park, na Inglaterra.

As unidades alemãs que se reuniram utilizavam carvão em vez de madeira para cozinhar para reduzir a fumaça e reduzir as chances de observadores aliados deduzir que um acúmulo de tropas estava em andamento. Por estas razões, o Alto Comando Aliado considerou as Ardenas um setor silencioso, contando com avaliações de seus serviços de inteligência e que os alemães não conseguiriam lançar nenhuma grande operação ofensiva no final da guerra. Eles levaram os Aliados a acreditarem precisamente no que os alemães queriam que eles acreditassem, que os preparativos estavam sendo realizados apenas para operações defensivas, não ofensivas. Os Aliados confiaram demais na máquina de decodificar códigos inglesa Ultra, não no reconhecimento humano. Na verdade, por causa dos esforços dos alemães, os Aliados foram levados a acreditar que um novo exército defensivo estava sendo formado em torno de Dusseldorf, no norte da Renânia, possivelmente para se defender contra o ataque britânico.

Deslocamentos de Tropas Alemãs

Essas previsões foram amplamente descartadas pelos americanos e embora ao 12º Grupo de Exércitos, Strong havia informado em dezembro de suas suspeitas. Bedell Smith então enviou Strong para avisar o Tenente-General Omar Bradley, o comandante do 12º Grupo de Exércitos, do perigo. A resposta de Bradley foi sucinta: "Deixe-os vir." O historiador Patrick K. O'Donnell escreve que em 8 de dezembro de 1944 os Rangers, com grande custo, tomaram a Colina 400 durante a Batalha da Floresta de Hertgen.

Como as Ardenas eram consideradas um setor tranquilo, levaram-na a ser usada como um campo de treinamento para novas unidades e uma área de descanso para unidades que tinham vindo de combates difíceis. As unidades americanas deixadas nas Ardenas eram, portanto, uma mistura de tropas inexperientes e tropas endurecidas por batalhas enviadas para esse setor para se recuperar. Duas grandes operações especiais alemãs foram planejadas para a ofensiva. Em outubro, foi decidido que Otto Skorzeny, o SS-Commando que havia resgatado o ex-ditador italiano Benito Mussolini, lideraria uma força-tarefa de soldados alemães de língua inglesa na Operação Greif. Esses soldados deveriam estar vestidos com uniformes americanos e britânicos e usar etiquetas tiradas de cadáveres e prisioneiros de guerra. Seu trabalho era ir atrás das linhas americanas e mudar as placas de sinalização, direcionar o tráfego, geralmente causar perturbações e tomar pontes através do rio Meuse. No final de novembro, outra operação especial ambiciosa foi adicionada. Friedrich August von der Heydte lideraria um Fallschirmjoger - Kampfgruppe (grupo de combate paraquedista) na Operação Stússer, um lançamento de para-quedistas à noite atrás das linhas aliadas destinadas a capturar um cruzamento de estrada vital perto de Malmedy.

Massacres de Malmedy

As 4:30 da manhã de 17 de dezembro de 1944, a 1ª Divisão Panzer SS estava aproximadamente 16 horas atrasada quando os comboios partiram da aldeia de Lanzerath, a caminho do oeste, para a cidade de Honsfeld. Depois de capturar Honsfeld, Peiper desviou de sua rota designada para apreender um pequeno depósito de combustível em Bollingen, onde a infantaria Waffen-SS executou sumariamente dezenas de soldados americanos. Depois, Peiper avançou para o oeste, em direção ao rio Meuse e capturou Ligneuville, contornando as cidades de Medersheid, Schoppen, Ondenval e Thirimont. O terreno e a má qualidade das estradas dificultaram o avanço do Kampfgruppe Peiper; na saída para a aldeia de Thirimont, a ponta de lança blindada foi incapaz de percorrer a estrada diretamente para Ligneuville, e Peiper desviou-se da rota planejada, e em vez de virar para a esquerda, a ponta de lança blindada virou-se para a direita, e avançou em direção às encruzilhadas de Baugnez, que era equidistante da cidade de Waimes de Ligne.

No dia 17 de dezembro, às 12h30, o Kampfgruppe Peiper estava perto da aldeia de Baugnez, na altura a meio caminho entre a cidade de Malmedy e Ligneuville, quando encontraram elementos do 285º Batalhão de Observação de Artilharia de Campo, a 7ª Divisão Blindada Americana. Depois de uma breve batalha, os americanos levemente armados se renderam. Eles foram desarmados e, com alguns outros americanos capturados anteriormente (aproximadamente 150 homens), enviados para ficar em um campo perto da encruzilhada. Cerca de quinze minutos depois que a guarda avançada de Peiper passou, um Corpo de Soldados sob o comando da SS- Sturmbannf-hrer Werner Ptschke chegou. Os soldados da SS de repente abriram fogo contra os prisioneiros. Assim que o tiroteio começou, os prisioneiros entraram em pânico. A maioria foi baleada onde estavam, embora alguns conseguiram fugir. Os relatos do assassinato variam, mas pelo menos 84 dos prisioneiros de guerra foram assassinados. Alguns sobreviveram, e as notícias dos assassinatos de prisioneiros de guerra se espalharam pelas linhas aliadas. Após o fim da guerra, soldados e oficiais de Kampfgruppe Peiper, incluindo Peiper e o General da SS Dietrich, foram julgados pelo incidente no julgamento do massacre de Malmedy.

Massacre de Malmedy

Wereth

Outro massacre menor foi cometido em Wereth, na Bélgica, aproximadamente 6,5 milhas (10,5 km) a nordeste de Saint-Vith em 17 de dezembro de 1944. Onze soldados negros americanos foram torturados depois de se renderem e depois baleados por homens da 1ª Divisão Panzer da SS pertencentes ao Schnellgruppe Knittel. Alguns dos ferimentos sofridos antes da morte incluíam ferimentos de baioneta na cabeça, pernas quebradas e seus dedos cortados. Os perpetradores nunca foram punidos por este crime. Em 2001, um grupo de pessoas começou a trabalhar em uma homenagem aos onze soldados negros americanos para lembrar seus sacrifícios.

OUTRAS AÇÕES ALEMÃS

O Kampfgruppe Peiper chegou em frente a Stavelot. As forças de Peiper já estavam atrasadas em seu cronograma por causa da forte resistência americana que recuou, seus engenheiros explodiram pontes e esvaziaram depósitos de combustíveis. Eles levaram 36 horas para avançar da região de Eifel para Stavelot, enquanto o mesmo avanço exigia nove horas em 1940. O Kampfgruppe Peiper atacou Stavelot em 18 de dezembro, mas não foi capaz de capturar a cidade antes que os americanos evacuassem um grande depósito de combustível. Três tanques tentaram pegar a ponte, mas o veículo foi desativado por uma mina. Depois disso, 60 granadeiros avançaram, mas foram parados por fogo defensivo americano concentrado. Depois de uma feroz batalha de tanques no dia seguinte, os alemães finalmente entraram na cidade quando os engenheiros americanos não conseguiram explodir a ponte.

Os americanos da 99ª Divisão de Infantaria, superada em número de cinco para um, infligiu baixas na proporção de 18 para um. A divisão perdeu cerca de 20% de sua força efetiva, incluindo 465 mortos e 2.524 evacuados devido a ferimentos, fadiga ou pé de trincheira. As perdas alemãs foram muito maiores. No setor norte oposto ao 99ª mais de 4.000 mortes e a destruição de 60 tanques e grandes armas:

O historiador John S. D. A. Eisenhower escreveu:"... a ação da 2ª e 99ª Divisões no lado norte poderia ser considerada a mais decisiva da campanha das Ardenas."

A defesa americana rígida impediu os alemães de alcançar a vasta gama de suprimentos perto das cidades belgas de Liége e Spa e da rede rodoviária a oeste da Cordilheira Elsenborn, levando ao rio Meuse. Depois de mais de 10 dias de intensa batalha, eles expulsaram os americanos das aldeias, mas foram incapazes de desalocá-los do cume, onde elementos do V Corpo do Exército Americano impediu as forças alemãs de chegar à rede rodoviária para oeste.

Massacre de Chenogne

Após o massacre de Malmedy, no dia de Ano Novo de 1945, depois de ter recebido anteriormente ordens para não fazer prisioneiros, soldados americanos executaram cerca de sessenta prisioneiros de guerra alemães perto da aldeia belga de Chenogne (8 km de Bastogne).

Pontes do Rio Meuse

Para proteger as travessias do rio no Meuse em Givet, Dinant e Namur, Montgomery ordenou que essas poucas unidades disponíveis mantivessem as pontes em 19 de dezembro. Isso levou a uma força reunida às pressas, incluindo tropas de alto escalão, policiais militares e pessoal da Força Aérea do Exército. A 29ª Brigada Blindada Britânica da 11ª Divisão Blindada Britânica, que havia entregue seus tanques para reequipar, foi orientada a recuperar seus tanques e ir para a área. O British XXX Corps. foi significativamente reforçado para este esforço. As unidades do corpo que lutaram nas Ardenas foram as 51ª (Highland) e a 53ª Divisões de Infantaria (galesa), a 6ª Divisão Aerotransportada Britânica, as 29ª e 33ª Brigadas Blindadas e a 34ª Brigada de Tanques.

O Cerco de Bastogne

Altos comandantes aliados se reuniram em um bunker em Verdun em 19 de dezembro. O Gen. Eisenhower, percebendo que os Aliados poderiam destruir as forças alemãs muito mais facilmente quando estavam a céu aberto e na ofensiva do que se estivessem na defensiva, disse a seus generais:

"A situação atual deve ser considerada como uma oportunidade para nós e não de desastre. Haverá apenas rostos alegres nesta mesa.”

Patton, percebendo o que Eisenhower sugeriu, respondeu:

"Inferno, vamos ter a coragem de deixar os bastardos irem até Paris. Então, vamos cortá-los e mastigá-los."

Eisenhower, depois de dizer que não estava tão otimista, perguntou a Patton quanto tempo levaria para transportar seu Terceiro Exército, localizado no nordeste da França, para contra-atacar. Para a descrença dos outros generais presentes, Patton respondeu que ele poderia atacar com duas divisões dentro de 48 horas. Desconhecido por outros oficiais presentes, antes de sair, Patton ordenou que sua equipe preparasse três planos de contingência para uma virada para o norte, pelo menos, força. No momento em que Eisenhower perguntou-lhe quanto tempo levaria, o movimento já estava em andamento. Em 20 de dezembro, Eisenhower removeu o primeiro e o nono exércitos norte-americanos. O 12º Grupo de Exércitos do Gen. Omar Bradley foi deslocado para o 21º Grupo de Exércitos de Montgomery.

Em 21 de dezembro, os alemães cercaram Bastogne, que foi defendida pela 101ª Divisão Aerotransportada, o 969º Batalhão de Artilharia Afro-Americano e o Comando de Combate B da 10ª Divisão Blindada. As condições dentro do perímetro eram difíceis, a maioria dos suprimentos médicos e o pessoal médico havia sido capturado. A comida era escassa e, em 22 de dezembro, a munição de artilharia era restrita a 10 cartuchos por arma por dia. O tempo limpou no dia seguinte e os suprimentos (principalmente munição) foram lançados em quatro dos cinco dias seguintes. A temperatura durante esse mês de janeiro foi extremamente baixa, o que exigia que as armas fossem mantidas aquecidas e os motores de caminhões ligados a cada meia hora para evitar que seu óleo se congelasse. A ofensiva avançou independentemente disso.

Pensamentos de Hitler O plano e o momento para o ataque de Ardenas surgiram da mente de Adolf Hitler. Ele acreditava que existia uma linha de falha crítica entre os comandos militares britânicos e americanos, e que um duro golpe na Frente Ocidental iria quebrar esta aliança. O planejamento para a ofensiva "Watch on the Rhine" enfatizou o sigilo e o compromisso de força esmagadora, através de comunicações terrestres dentro da Alemanha, corredores motorizados carregando ordens, e ameaças draconianas de Hitler.

Infelizmente para os planos alemães as forças empregadas não resultaram em sucesso.

PERDAS

A Batalha do Bulge foi a batalha mais sangrenta para as forças dos USA durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial. Um relatório preliminar do Exército restrito ao Primeiro e Terceiro Exécitos dos USA listaram 75.482 vítimas (8.407 mortos, 46.170 feridos e 20.905 desaparecidos). As perdas britânicas do XXX Corpo até 17 de janeiro de 1945 foram registradas como 1.408 (200 mortos, 969 feridos e 239 desaparecidos). Dupuy, David Bongard e Richard Anderson listam as vítimas nessas unidades de combate em 1.462, incluindo 222 mortos, 977 feridos e 263 desaparecidos até 16 de janeiro de 1945.

As baixas entre as divisões americanas (excluindo elementos anexados, corpo e apoio de combate ao nível do exército e pessoal da área traseira) totalizaram 62.439 de 16 de dezembro de 1944 a 16 de janeiro de 1945, inclusive: 6.238 mortos, 32712 feridos e 23.399 desaparecidos. O historiador Charles B. MacDonald lista 81.000 vítimas americanas, 41.315 durante a fase defensiva e 39.672 durante o esforço para achatar o "Bulge" até 28 de janeiro.

Um relatório oficial do Departamento do Exército dos Estados Unidos lista 105.102 baixas para toda a campanha "Ardenas-Alsácia", incluindo 19.246 mortos, 62.489 feridos e 26.612 mortos ou desaparecidos; este número incorpora perdas não apenas para a Batalha do Bulge, mas também todas as perdas sofridas durante o período por unidades com o crédito de batalha "Ardenas-Alsace" (todos os USA). Primeiro, Terceiro e Sétimo Exércitos, que inclui perdas sofridas durante a ofensiva alemã na Alsácia, Operação Nordwind, bem como forças envolvidas nas campanhas do Sarre e Lorena, e a Batalha da Floresta de Fortrgen durante esse período de tempo. Para o período de dezembro de 1944 - janeiro de 1945 em toda a frente ocidental, Forrest Pogue dá um total de 28.178 militares dos USA capturados.

O Alto Comando alemão estimou que eles perderam entre 81.834 e 98.024 homens na Frente Ocidental entre 16 de dezembro de 1944 e 25 de janeiro de 1945; o número aceito foi de 81.834, dos quais 12.652 foram mortos, 38.600 foram feridos e 30.582 estavam desaparecidos. As estimativas aliadas sobre as baixas alemãs variam de 81.000 a 103.900. As estimativas de Dupuy baseadas em registros alemães fragmentados e testemunhos orais sugerem que as baixas entre divisões e brigadas sozinhas (excluindo elementos anexados, corpo e apoio de combate ao nível do exército e pessoal da área traseira) totalizaram 75.459 de 16 de dezembro de 1944 a 16 de janeiro de 1945, inclusive: 11.048 mortos, 34.168 feridos e 29.243 desaparecidos. O historiador alemão Hermann Jung lista 67.675 baixas de 16 de dezembro de 1944 até o final de janeiro de 1945 para os três exércitos alemães que participaram da ofensiva. Os relatórios de vítimas alemãs para os exércitos envolvidos contam com 63.222 derrotas de 10 de dezembro de 1944 a 31 de janeiro de 1945. Os números oficiais do Centro de Exército dos Estados Unidos da História Militar são 75.000 vítimas americanas e 100.000 vítimas alemãs.

Soldados Prisioneiros Americanos na região das batalhas

Soldados Aliados em deslocamento pela floresta gelada

Resultado

Embora os alemães tenham conseguido começar sua ofensiva com total surpresa e tenham desfrutado de alguns sucessos iniciais, eles não conseguiram aproveitar a iniciativa na Frente Ocidental. Embora o comando alemão não tenha alcançado seus objetivos, a Operação Ardenas infligiu pesadas perdas e atrasou a invasão aliada da Alemanha por várias semanas. O Alto Comando das forças aliadas tinha planejado retomar a ofensiva no início de janeiro de 1945, após as chuvas da estação chuvosa e geadas severas, mas esses planos tiveram que ser adiados até 29 de janeiro de 1945 em conexão com as mudanças inesperadas na frente.

As derrotas alemãs na batalha foram especialmente críticas: suas últimas reservas já haviam desaparecido, a Luftwaffe havia sido quebrada e as forças remanescentes em todo o Ocidente estavam sendo empurradas para trás para defender a Linha Siegfried.

Durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, a maioria dos soldados negros dos USA ainda serviam apenas em cargos de manutenção ou serviços, ou em unidades segregadas. Por causa da escassez de tropas durante a Batalha do Bulge, Eisenhower decidiu integrar o serviço pela primeira vez. Este foi um passo importante para um exército desagregado dos Estados Unidos. Mais de 2.000 soldados negros se ofereceram para ir para a frente. Um total de 708 negros americanos foram mortos em combate durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Créditos de Batalha

Após o fim da guerra o Exército Americano emitiu crédito de batalha na forma da citação da campanha Ardenas-Alsace para unidades e indivíduos que participaram de operações no noroeste da Europa. A citação cobriu as tropas no setor de Ardenas, onde a principal batalha ocorreu, bem como unidades mais ao sul no setor, incluindo aquelas no norte da Alsácia que preencheram o vácuo criado pelo exército americano.

RESUMO DA EVOLUÇÃO DA BATALHA Entre idas e vindas os avanços e retrocessos de ambas as partes elevaram ainda mais o tempo de conflito. Os próprios desentendimentos entre o Alto Comando Alemão sugerindo à Hitler mudanças nos planos que este não quis fazê-lo. Entre os Aliados as brigas entre os seus Generais Americanos e Ingleses pelas preferências e vaidades sobre prioridades e abastecimentos principalmente, atrasaram muito o encerramento desta batalha.

No momento preciso o Gen. Eisenhower Comandante em Chefe do SHAEF acabou colocando Montgomery, Patton e Bradley nos lugares corretos pela preferência no fornecimento.

-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-

No próximo post o início de um novo trabalho.

Até lá!

Forte Abraço

Osmarjun

0 notes

Photo

me drinking my 3rd coffee, trying to convince myself that THIS ONE will surely help me waking up

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max, one more time, where yo clothes at⁉️

This goes to kurt, dietrich and fritz too, where all of yo clothes at😭

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grandpa Dietrich

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Desert Fox: Separating the myth and the man of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Sweat saves blood, blood saves lives, and brains saves both.

- Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

War hero or Nazi villain? Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is, to this day, the subject of heated debate. He was the “Desert Fox,” revered by Allied Forces for his supposed chivalry, and allegedly implicated in the “Valkyrie” plot to assassinate Hitler.

But present day historians have increasingly come to re-examine the life and the legend of this most iconic of World War Two generals.

I first became interested in this question after reading Corelli Barnett’s magisterial account ‘The Desert Generals’ back when I was in Sandhurst. I read other World War Two books before then of course but it was only at Sandhurst did I first give serious consideration towards Rommel as ‘the Good German’ general. I read other books too like General Sir David Fraser’s ‘Knight’s Cross: a life of Field Marshal Rommel’ as a stand out one on military stuff but a very cursory examination of his early life and beliefs.

Rommel was a legend in the making.

Whichever side of the debate one falls on there is no doubt that Erwin Rommel, was one of the most celebrated and respected generals of the Second World War and indeed, some even say one of the greatest generals of all time. His prowess on the battlefield earned him more than a battlefield earned him the admiration of both his men and his enemies alike, with adversaries lining up to pay tribute to their greatest foe in the field.

“We have a very daring and skilful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general,” said no less than Winston Churchill himself of Rommel, just after the war ended in his book on the conflict, The Second World War.

When Churchill came under fire in the press for praising a man seen as a Nazi, he doubled down, commenting “He also deserves our respect because, although a loyal German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his works, and took part in the conspiracy to rescue Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant.

For this, Rommel paid the forfeit of his life. In the sombre wars of modern democracy, chivalry finds no place�� Still, I do not regret or retract the tribute I paid to Rommel, unfashionable though it was judged.”

Indeed, the extent to which Rommel was a Nazi is one of the great questions that has been asked since the war and one that is debated to this day. Rommel, while respected by those who fought him from afar as generals and indeed, thought of a genius to many of those who fought beneath him in the Wehrmacht, has often faced criticism of his tactics and his decision making, with some post-war writers holding him up as a man prone to erratic behaviour on the battlefield and a great sufferer from the stresses of the job.

“Rommel was jumpy, wanted to do everything at once, then lost interest. Rommel was my superior in command in Normandy. I cannot say Rommel wasn’t a good general. When successful, he was good; during reverses, he became depressed,” said Sepp Dietrich, who fought under Rommel in France and ended the war as the most senior figure in the Waffen-SS.

A similar sentiment was expressed by Luftwaffe field marshal Albert Kesselring, a contemporary of Rommel’s and an officer of similar rank, who later wrote: “He was the best leader of fast-moving troops but only up to army level. Above that level it was too much for him. Rommel was given too much responsibility. He was a good commander for a corps of army but he was too moody, too changeable. One moment he would be enthusiastic, next moment depressed.”

Who was this great man then? We know him today as a great tactician, a charismatic leader, a respected general and the last German participant in the so-called “clean war”. But how true are those assessments? Was the Desert Fox as chivalrous as his enemies thought him to be?

Rommel was far from just a Second World War hero – he distinguished himself in World War One too.

Rommel graduated from the military academy in Gdansk – then known as Danzig and an integral part of Germany – in 1912 and was immediately posted back to his home region of Baden-Württemberg.

When war broke out in 1914, Rommel was ready to face his first major conflict posting. As a battery commander within the 124th division of the German army, he would distinguish himself and gain his first recognition from the higher-ups.

Erwin saw his first action at the age of 23 on August 22, 1914, near the French town of Verdun. Rommel led his platoon into a French garrison, catching them by surprise and personally leading the charge ahead of the rest of his men, earning credits for bravery and ingenuity. He would be awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, for his actions, a promotion to First Lieutenant and a transfer into the Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion as a company – rather than platoon – commander.

Rommel would go on to fight in the German campaigns in Italy and Romania, with particular note being taken by the German Army hierarchy of his conduct in the Italian campaign. The Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion fought at the Battle of Caporetto, the twelfth battle to be fought along the Isonzo River in modern-day Slovenia, and one that would go down as probably the largest military defeat in the history of Italy.

Rommel would play a central role, leading the Royal Württemberg, with just 150 men, to capture an estimated 9,000 Italians, complete with all their guns, for a cost of just 6 of his own men.

The young Rommel used the challenging, mountainous terrain of Caporetto – now known as Kobarid – to outflank the Italians and convince them that they were totally encircled by Germans, when in fact there was just one battalion. Fearing that they were surrounded, the Italians surrendered en masse and were surprised to find that so few men were able to capture them.

The efforts of the German Army to break into the Italian Front through the Slovenian Alps – at the time, part of Italy – were vital in furthering an advance towards Venice, though the Germans were eventually stopped and turned back.

Rommel was awarded the Pour Le Merite award by the Kaiser for his leadership at Caporetto, but also gained the respect and loyalty of his men, who were not only impressed by the way in which his tactics had won the battle, but also by the way that he had stood up to the German Army high command and argued for more and better food for his men. The legend of Rommel was growing apace.

Rommel was an effective teacher as well as a military leader.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that Rommel was a capable teacher: his father had been a headmaster, while the ability to communicate his ideas effectively in the field would lead to some of his most enduring military victories. There was no point coming up with a revolutionary tactic to win a battle if you couldn’t then inform and inspire your men well enough for them to then go and carry it out.

At the end of the First World War, Rommel was entering his late 20s and had already been widely feted for his military prowess. While it might have seemed a little dull compared to the derring-do on the Isonzo, the role of the Royal Württenberg Mountain Battalion lay much closer to home, with German society slowly disintegrating into civil wars between, on the left, socialists who wanted Germany to undergo a revolution similar to that which had recently occurred in Russia, and on the right, groups such as the Freikorps, disgruntled ex-soldiers and nationalist, anti-communist paramilitaries that would go on to form the kernel of the Nazi Party.

Rommel, recently promoted again to the rank of Captain, was ordered to use his soldiers in a policing capacity, putting down insurrections all over southern Germany. It was during this period that he showed some of the sense of restraint that would distinguish his conduct in North Africa during World War Two, trying to avoid the use of force against crowds of civilians where possible.

After the Weimar Republic took hold, however, the country somewhat stabilised and Rommel found himself in Dresden, teaching new recruits. He had been promoted in turn to Major, then Lieutenant Colonel, placing him in the very highest echelons of the Treaty of Versailles-reduced German Army.

He was recognised as one of the prime instructors in that army and wrote a book, “Infantry Attacks”, that furthered his theories on warfare and explained his experiences in the Izonzo – it sold incredibly well and increased Rommel’s personal fame, as well as bringing him to the attention of Adolf Hitler, who was known to have read the book.

Rommel met Hitler in Goslar, Germany in 1934, while Rommel was posted as battalion commander. Hitler’s charisma and promises to reestablish Germany as a world power after the crippling results of World War I inspired Rommel to become a fervent supporter of the Nazi Party.

The two men had several encounters following this, and Rommel rose through the ranks on Hitler’s personal recommendation. But it was ultimately Hitler’s liking for Rommel’s book Infantry Attacks that led to his becoming the commander of Hitler’s personal guards during his tour of the Sudetenland.

By the 1930s with Hitler fully secured in power, the German Army, for whom Rommel worked, and the Nazi state were more and more inseparable. It would be this coming together that prompted a major dilemma for the career soldiers such as Rommel: did the duty lie to their country, and whoever might be governing it, or to the party, that was coming to define what that country was about?

Rommel was a committed Nazi and not the “decent face” of the German Army.

Rommel’s antagonism wasn’t so much against Nazism as it was towards the Nazis in leadership who led it. His committment to Nazism eroded as the war took a wrong turn and as Hitler increasingly became erratic in his military decision making that Rommel grew increasingly frustrated.

Just how much of a Nazi Rommel was is one of the biggest questions that is debated about him to this day. It is largely due to the Rommel myth that was perpetuated by the likes of Winston Churchill after the war that Rommel was taken by the victorious Allies as “the good Nazi”, or the honest general who happened to be being ordered about by the Nazis, merely a career soldier who followed orders and stayed out of politics.

Let’s put that one to bed, here and now. Rommel was an early adopter of the Nazi Party and a committed believer in the ideals of National Socialism, while also being an officer who regularly disobeyed orders – making both commonly held assumptions wrong.

That said, he is one of the few figures of that period who is still revered in Germany, who still has streets named after him and memorials in his honour. It seems that the myth persists in his homeland too, despite countless books and articles to the contrary.

One such author attempting to shake this idea from the public consciousness is Wolfgang Proske, a historian and history professor from Rommel’s hometown on Heidenheim, who has written 16 books about his town’s most famous son. “Rommel was a deeply convinced Nazi and, contrary to popular opinion, he was also an anti-Semite. It is not only the Germans who have fallen into the trap of believing that Rommel was chivalrous. The British have been convinced by these stories as well,” he told British newspaper The Independent in 2011 when a new memorial to the Field Marshal was unveiled.

“At the time when Rommel marched into Tripoli, more than a quarter of the city’s population were Jews,” Proske continued, “There is evidence which shows that Rommel forbad his troops to buy anything from Jewish traders. Later on, he used the Jews as slave laborers. Some of them were even used as so-called ‘mine dogs’ who were ordered to walk over minefields ahead of his advancing troops.”

While Rommel was never a member of the Nazi Party, it is widely known that Wehrmacht figures, particularly high-ranking ones such as Rommel, welcomed Hitler coming to power. Those, like Rommel, whose backgrounds had shut them off from the highest ranks of the Kaiser’s forces, saw the new government as one that would see them move to the top of the tree and as such were generally in favor of it.

Goebbels himself wrote in 1942, when Rommel was in the running for the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, that the Field Marshal was ”ideologically sound, is not just sympathetic to the National Socialists. He is a National Socialist; he is a troop leader with a gift for improvisation, personally courageous and extraordinarily inventive. These are the kinds of soldiers we need.”

Rommel owes a large part of his fame to the fact that he made fools of opposing general - well almost (Patton would disagree).

Rommel’s prowess as a general is unquestioned. On the back of his heroics as a low-level officer in World War One added to by his role teaching at the forefront of modern military tactics, he was perfectly positioned to lead the Nazi war machine into the second conflict.

When the war began, he was leading Hitler’s personal protection battalion – so much for a man who kept a distance from the center of Nazi power – and thus was privy to the highest levels of discussions regarding tactics, particularly the way in which to use mechanized infantry such as tanks. After the early successes in Poland, Rommel moved with the front to France and commanded Panzer units, before distinguishing himself against the British at Arras and leading the drive towards Dunkirk.

With the British regrouping on the other side of the Channel after a crushing defeat – which, lest we forget, Dunkirk was – the focus turned to North Africa, where Rommel would lead the newly-established Afrika Korps. He was the superstar of the German Army, a reputation largely built on his ability to vanquish the British, whom he would now face again in the desert. It was at this time that his nickname, The Desert Fox, was coined by the British press, who sought to create a figure against which the war could be fought.

The legacy of Rommel as the acceptable Nazi could be seen to stem from this point when the media in Britain saw fit to create a worthy adversary for their troops to combat. Rommel was thought to be an old-style soldier rather than an out-and-out Nazi: though we have seen that he was a Nazi, and he had arguably committed war crimes by summarily executing prisoners in France just weeks before.

Come the victory of the British at Tobruk and El Alamein, the British propaganda machine had even more than a noble adversary. They had a noble adversary against whom they had lost in Europe and then subsequently defeated: when the characters of the British side, Auchinleck and Montgomery, were spoken of, they needed someone of equal weight to make their victories seem even more heroic, a role that fit Rommel perfectly.

With morale at home low after the Dunkirk evacuation, the victories in North Africa were vital to keeping spirits up, and a glorious victory against an equally glorious enemy sounded even better. Churchill himself called Rommel an “extraordinary bold and clever opponent” and a “great field commander” in the House of Commons in 1942 – after he had just been defeated.

Rommel’s reputation for chivalry in North Africa might not just be down to his own intentions.

Of course, some aspects the Allied propaganda about Rommel – that he was a fair fighter, that he respected the ideals of chivalry when other Germans didn’t – were generally true.

It is undoubted that, by and large, Rommel adhered to the rules of war when plenty of Nazi generals didn’t, but it bears mentioning that the reason that so many German generals were so callous is that they were ordered to be like that. Orders within the Nazi war machine came down from high and were often brutal in their nature: summary execution of prisoners, rounding up of Jews and other minorities, scorched earth policies. That was just the orders aimed at enemies: often generals would be ordered to stand their ground to the death when all military logic told them to make a tactical retreat.

Rommel’s dedication to upholding the “war without hate” as he called the more traditional methods of war is up for debate, but certainly, he did take measure to negate the harsher aspects. That said, there are other factors that question whether his commitment to the “war without hate” was intentional, circumstantial or ideologically-driven.

When most German generals were likely to commit acts of ethnic cleansing, Rommel was not generally faced with the question. North Africa, where this reputation was developed, had hardly any Jews, for example, and other potential targets for Nazi aggression were protected by being citizens of Italy and Rommel was wary of standing on the toes of their allies. That said, many within the North African Jewish community are reported as having felt that they were spared from the horrors suffered by Jews in Europe by the actions of the Afrika Korps, led by Rommel.

It is also widely accepted that he refused to execute captured Jewish prisoners and hated the use of slave labour. As far as his own troops were concerned, Rommel repeatedly refused orders directly from Hitler. When, at the end of the second Battle of El Alamein, Hitler commanded him directly not to retreat and to show his soldiers “no other road than that to victory or death.”

Knowing that it was impossible for him to defeat the advancing British, who massively outnumbered his forces, Rommel chose to ignore the letter from the Fuhrer and fled all the way across North Africa to Tunisia rather than face death in the sand. While he was way too politically powerful to be censured by Hitler, actions such as this were contributory to a wider feeling among the Nazi hierarchy that Rommel was not one of them.

He was a PR superstar in Germany, but was both respected and later suspected by the Nazi leadership.

Rommel’s reputation within Germany might well have made him untouchable for the Nazi hierarchy, even when he did things that were in direct contradiction of the ideological and military strategy of the regime. They had invested so much time and so much weight in making him the poster boy of their propaganda regime that, when Rommel turned out to be less than what they had hoped for, they could not easily dispose of him.

On paper, he was the perfect fit for their media machine: he was an early adopter of Nazism, already a hero from the First World War and an excellent general, with victories aplenty. Moreover, they could cite the Allies reverence for him in their favor, and Rommel himself was comfortable in the spotlight and relished the attention.

Hitler was always wary of building up any one single figure too far – lest he be challenged himself – but Goebbels, the chief propagandist, knew an opportunity when he saw it and Rommel could not be passed up. As Rommel’s media image grew and grew, he became the darling of the public back home, but in the corridors of power in Berlin, there were plenty of higher-ups who were less convinced of his powers.

Even from the early days of the war in 1941, when Rommel was in France, some of those who fought alongside him were doubting just how effective he actually was a general. By the time that the war in North Africa had turned against him in 1943, the German furthest expansions were contracting: the Battle of Stalingrad had been lost in February and Rommel departed Tunisia in May.

It might have made sense if the Nazis had thought Rommel their best general, to send him to the Eastern Front where the war was being lost. Perhaps, too, the brutal nature of the war on the Ostfront was seen as beyond Rommel’s nature: this was not the time or place for “war without hate”, in the eyes of the Nazi leadership.

Instead, he was dispatched to Italy. As Italy fell, Rommel was demoted from the head of the campaign to second in command to Albert Kesselring, alongside whom he had served throughout the North Africa campaigns.

Later in France, Rommel was the man in charge of building the Atlantic Wall that would protect Nazi-occupied France from Allied invasion: though he had warned heavily that his experiences in North Africa had taught him that land and sea defences would be nothing if air supremacy allowed the Allies to destroy the Nazi army from above, Rommel was ignored.

After the defeat in North Africa, the retreat through Greece and Italy and the failure to stop the D-Day invasions, his reputation as a superstar general back home was in tatters.

Rommel’s reputation got a huge boost because of a 1951 film.

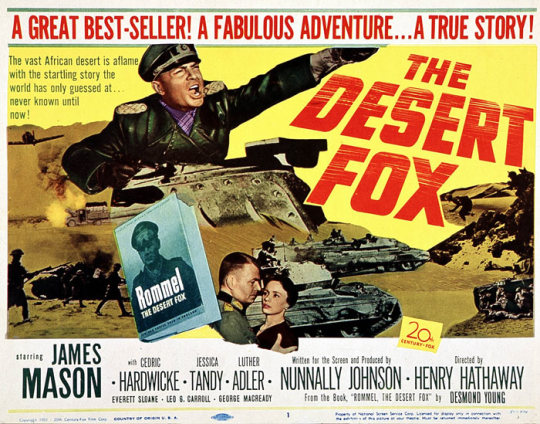

If Rommel’s reputation as a great leader was undermined by the catastrophic defeats on the African, Italian and Western Fronts in the last two years of the war, why was it that the so-called “Rommel Myth” was so pervasive after the war? The theories are numerous, but one major contributing factor must be the success of the 1951 film, The Desert Fox. Rommel was played by the iconic actor James Mason who won critical acclaim for his role.

Rommel was a well-known figure in Allied countries and in 1950, the first biography of the “good German” was released in the UK. Written by Desmond Young, a British brigadier-general who had himself been captured by Rommel during the war, “Rommel: The Desert Fox” was incredibly popular in Britain and cemented the position of the vanquished general as the acceptable enemy.

His later involvement in the 1944 plot against Hitler did a lot to wash Rommel of the stain of Nazism – conveniently forgetting the decade or so that he had spent close to the top of the regime – and his position as the general who was beaten “fair and square” endeared him to a British audience. After all, it’s much easier to build heroes of your own generals when they have beaten a general that you also respect.

The 1951 film of The Desert Fox further spread the myth and was widely popular in the UK. The narrative of Rommel, the good German, being defeated by the heroic British in the clean war in North Africa was a far more palatable one in the burgeoning Cold War than one that emphasised the horrible destruction that had come through the Soviet victory in the East.

There could be little appetite for a war with Russia when people were constantly being reminded of the horrific images that had emerged from the Eastern Front. Thus, the clean general of the fair fight in North Africa was an enticing idea.

The Germans, too, were all too pleased to go along with Rommel as their figurehead. Their army had been severely curtailed after their defeat, but there was a clamour to de-Nazify the Wehrmacht and remove the stigma from the German armed forces. The Bundeswehr, the new German army, was more palatable to a post-war world when it could be seen as the legacy of good soldiers lead by bad politicians rather than an integral and vital part of the Nazi war machine.

Thus, the idea of The Desert Fox was created and, to a large extent, still persists. He remains the only Nazi to be lionised within Germany: public squares and streets bear his name, as does the largest barracks of the Bundeswehr. Whether such a status is deserved, however, is still a question about which historians continue to argue.

During the first half of 2020 many countries have been reconsidering the roles of their historical figures - remembered in statue form - due to their controversial views or actions from today’s point of view. In Britain, France and Belgium, statues of figures associated with the colonial past have become the target of public criticism in some quarters. In the United States, not only statues of Confederate figures who defended slavery during the American Civil War were destroyed or even demolished, but also, for example, the discoverer of America, Christopher Columbus.

In Germany a similar process was also underway. The monument to the Wehrmacht Marshal Erwin Rommel in Heidenheim came under severe renewed scrutiny.

Germany's memorial to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is perched on a hillside overlooking the middle-class town of Heidenheim an der Brenz where he was born 120 years ago. The words inscribed on the white limestone monument describe the legendary Second World War general as "chivalrous", "brave" and as a "victim of tyranny"

The monument, which was built in 1961 by the German Afrikakorps Association, aroused long-term controversy and in the past was repeatedly damaged by inscriptions that called Rommel a Nazi. In 2014, Heidenheim City Hall expressed its intention to contrast the monument with another memorial building. By 2020 those calls took on a greater momentum.

The German artist Rainer Jooss was brought in by the municipal authorities to re-interpret the existing monument without having to destroy it completely. Jooss took as his starting point to focus on other parts of Rommel’s legacy. It was little known that Rommel had large minefields laid during the campaign of German troops in North Africa during World War II. In Libya and Tunisia alone, at least 3,300 people have lost their legs and another 7,500 have been maimed since the statistics were kept in the 1980s. So Jooss designed black silhouette cut out of a maimed child victim of war to complement the monument.

“The monument does not represent the truth, but encourages us to look for it,” said Bernhard Ilg, Mayor of Baden-Württemberg, at the presentation of the monument’s design unveiling in July 2020. Jooss was more stoic. Joos believed it would be a mistake to remove the Rommel monument altogether,"If we let grass grow over it, that would mean the end of the important task of dealing with history.”

The artist behind the modification to the Heidenheim monument said his statue was purposefully made to look small next to the impressive limestone bloc."I wanted to confront the monumental (features) of the original memorial with the fragility of a land mine victim.” Jooss wanted and hoped that it was up to “the next generations to make a picture of themselves based on factual histography.”

Yet eminent historians have since dismissed the fresh silhouette plaque as a transparent attempt to avoid addressing the deep seated questions about Rommel. Indeed Rommel’s privileged position to being seen as the ideal role model for the Bundeswehr (the unified armed forces of Germany and their civil administration and procurement authorities). While recognising his great talents as a commander, they point out several problems: such as Rommel's involvement with a criminal regime and his political naivete. However, there are also many supporters of the continued commemoration of Rommel by the Bundeswehr, and there remains military buildings and streets named after him and portraits of him displayed.

The politician scientist Ralph Rotte called for his replacement with Manfred von Richthofen. Historian Cornelia Hecht opined that whatever judgement history will pass on Rommel – who was the idol of World War II as well as the integration figure of the post-war Republic – it was now the time in which the Bundeswehr should rely on its own history and tradition, and not any Wehrmacht commander. Jürgen Heiducoff, a retired Bundeswehr officer, had written that the maintenance of the Rommel barracks' names and the definition of Rommel as a German resistance fighter are capitulation before neo-Nazi tendencies. Heiducoff agreed with Bundeswehr generals that Rommel was one of the greatest strategists and tacticians, both in theory and practice, and a victim of contemporary jealous colleagues, but argued that such a talent for aggressive, destructive warfare was not a suitable model for the Bundeswehr, a primarily defensive army. Heiducoff criticised those Bundeswehr generals for pressuring the Federal Ministry of Defence into making decisions in favour of the man who they openly admire.

Rommel has had his supporters from this avalanche of revisionist criticism. Historian Michael Wolffsohn supported the Ministry of Defense's decision to continue recognition of Rommel, although he thought the focus should be put on the later stage of Rommel's life, when he began thinking more seriously about war and politics, and broke with the regime. Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) reported that, "Wolffsohn declares the Bundeswehr wants to have politically thoughtful, responsible officers from the beginning, thus a tradition of 'swashbuckler' and 'humane rogue' is not intended".

According to authors like Ulrich vom Hagen and Sandra Mass though, the Bundeswehr (as well as NATO) deliberately endorses the ideas of chivalrous warfare and apolitical soldiering associated with Rommel. At a German Ministry conference soliciting input on the matter, Dutch general Ton van Loon advised the German Ministry that, although there can be historical abuses hidden under the guise of military tradition, tradition is still essential for the esprit de corps, and part of that tradition should be the leadership and achievements of Rommel. Historian Christian Hartmann opined that not only Rommel's legacy was worthy of tradition but the Bundeswehr "urgently needs to become more Rommel".

There are other historians who have tried to take a middle path on the continued controversy of Rommel’s legacy. Historian Johannes Hürter believed that instead of being the symbol for an alternative Germany, Rommel should be the symbol for the willingness of the military elites to become instrumentalised by the Nazi authorities. As for whether he can be treated as a military role model, Hürter writes that each soldier can decide on that matter for themselves. Historian Ernst Piper argued that it was totally conceivable that the Resistance saw Rommel as someone with whom they could build a new Germany. According to Piper though, Rommel was a loyal national socialist without crime rather than a democrat, thus unsuitable to hold a central place among role models, although he should be integrated as a major military leader.

Whether one is for and against Rommel such debates take place because he is dead in conveniently ambiguous circumstances.

Recovering from skull fractures in hospital, he missed the main event - the 20 July Bomb Plot 1944 - insitigated by other senior German army officers. Hitler survived the blast, and immediately set about executing the plotters.

While Rommel had lots of contact with many key conspirators and was generally aware of the movement(s) to assassinate Hitler, there is no direct evidence that he knew about the July 20th plot in advance, let alone was involved in any detailed planning. Several conspirators allegedly confessed during interrogation that he was involved and, like Speer, his name was found on Goerdeler’s list of possible participants in a new German government.

Rommel was listed among various possibilities for Reich President. Unfortunately for him, there was no question mark or other notation, as in Speer’s case, which indicated that he was unaware of the designation.

He maintained his innocence when confronted by General Burgdorff on the day he died and also told his wife and son that he had played no part in the events of July 20th. But ultimately, there’s no way to know what he was or was not aware of. He took that with him to the grave.

The list of members of the 20 July plot doesn´t name Rommel as part of the attempt to kill Adolf Hitler. But: Rommel was blamed of having known of plans to do so. So he was forced to commit suicide.

On 19 th October 1944 Rommel met two german generals at his home. They showed him pretended evidence about his paticipation in “operation valkyrie”, which he denied to be true. They accompanied him away from his home, where he swallowed a capsule filled with potassium cyanide and died. The two generals Wilhelm Burgdorf and Ernst Maisel , members of german court of military honour, who had handed over the capsule to Rommel, drove back to his home and contended that Rommel had died because of ramifications of an injury he received on 17th of July during an allied bombardement.

Given a choice between a trial, involving his disgrace, execution and his family’s impoverishment - and suicide - he chose the latter.

The story given to the public was that he’d died of wounds sustained in the air attack. He was named a “german hero”, was “honoured” with a state funeral an d buried in Herrlingen, Germany.

Had he lived who knows what his real fate might have been at the hands of the Allies. At the main Nuremberg trials, the two army generals prosecuted were Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Alfred Jodl. Both were accused of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity. Both were convicted on all four charges and hanged.

The principal charge against Keitel was the infamous 13 May 1941 Barbarossa Decree, which condemned captured prisoners and ensured a high level of brutality by German soldiers against Soviet civilians. Jodl was the author of the Commando decree – ordering that any Allied commandos encountered in Europe and Africa should be killed immediately without trial, even if in proper uniforms or if they attempted to surrender.

General Heinz Guderian is an example of a prominent German general who did survive the war but was not prosecuted for war crimes.

Another prominent example is Field Marshall Kesselring, who had commanded the defence of Italy after the Allies invaded. Kesselring was not prosecuted at Nuremburg, but did face a British military court in Italy. The Moscow declaration of October 1943 had stated that those accused of war crimes would be prosecuted in the country where they had committed their crimes. Although the trial was conducted in Italy, Italian judges did not participate as Italy was not considered an ally. Kesselring was prosecuted for the shooting of hundreds of Italian prisoners in retaliation for attacks on German soldiers. Kesselring was found guilty and condemned to death. British General Alexander, who had run the Italian campaign, and Winston Churchill pleaded for the sentence to be commuted - which it was. Kesselring was released in 1952 and lived until 1970.

By comparison Rommel was never accused of issuing similar decrees. Many felt that he was an honourable soldier. Nor was he ever accused of shooting prisoners in the way Kesselring was. Rommel’s military reputation is that of a highly professional soldier who carried out his duties according to a military code of ethics. His record is untainted by atrocities or unsavoury tactics against the enemy or civilian populations. He tended to live a charmed life early in the war.

Had he lived one can only speculate as to his fate and his legacy. Speculation regarding a possible role for him in the rebuilding of German forces for NATO, had he survived, is unrealistic. Rommel was never a strategically-minded commander. Indeed it is well known that Quartermasters hated him for his habit of outrunning his supplies on the battlefield.

The likelihood is he might well have been allowed to live without any kind of Allied retribution for war crimes as he was never guilty of any such departures from a strict military code of behaviour. But in trial - he would surely would have been put on trial even if he would be found not guilty - the messy details of his involvement with the Nazi regime would come to light. It would show that Rommel certainly benefited from the regime he served, and I think would have been considered guilty by association, even if his enthusiasm for Hitler waned in his final days.

Post-war, it would not have surprised me at all if the Allies had sought to build a West German government around Rommel. Staunchly anti-Communist, he nevertheless was seen widely as honourable and pro-West. But what role he would have been given - or what role the allies might have been able to make palatable to a war ravaged population - can only be speculated.

I suspect he would have served in some official capacity within the Bundeswehr before retiring to write his highly expected memoirs. It’s telling that Rommel’s chief of staff, Hans Speidel, drove the creation of the Bundeswehr and was the first to be named a generaloberst in that force. Later he was Supreme Commander of all NATO ground forces in Central Europe (which was almost all of it). It’s an intriguiing thought what Rommel might have played in a post-war Cold War Germany and Europe. Speidel and Rommel were inseparable and cut from the same bolt of cloth. Indeed it was Hans Speidel, who had been involved in the July 20 plot, wrote after the war that Rommel was a member of the resistance, (for which there is no evidence) that contributed towards Rommel and ‘The Good German’ Myth.

Given all that was “overlooked” by both the Allies and the German people after World War Two. There’s no logical reason to think that Rommel would not have been as honoured, if not more so, after the war. After all, one of the main Bundeswehr barracks continues to be named after him in 1965.

To me he was a great general rightly lauded by his peers and military historians - but not the best. Rommel was a highly competent tactical commander, but there were many such commanders in the Wehrmacht. His prominence is due to a number of things. Firstly, he was always Hitler favourite; secondly Goebbels played him up in his propaganda; and thirdly he fought the British and Americans and thus received much more attention in the Western press and historians after the War than the German commanders fighting the Soviets.

Indeed an argument can be made that by fighting in the Western Desert in a sector that the British had logistical and material superiority (and thus difficult to defeat), Rommel essentially taught the British and the Americans Blitzkrieg tactics - essentially modern warfare. His very inflated legacy saved the British from admitting their military performance in North Africa was abysmal until the Axis forces overextended their supply lines and the American supply of goods was able to compensate for substandard British equipment.

It’s also forgotten that Rommel also oversaw the building of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall which was essentially a fiction when he took over. Immense resources were poured into the project. The impact was to delay the Anglo-Americn invasion about 5 hours and only on one beach (Omaha).

And no matter how humane and honourable he was, Rommel was ultimately a weak man who chose to look away when it was convenient to his career to do so. Indeed I agree with many historians today that he was primarily bent on serving Hitler to advance his career. He was a man who believed he was serving a king and realises too late that he was a devil. I have little doubt that he was conflicted by that especially as it grew during the seven months of his life leading up to his death. Perhaps the best tactical military manoeuvre he made was to take the poison forced upon him and thereby save his family but also secure his legacy, even if that legacy remains mostly intact if a little more tarnished to this day.

#rommel#nazism#nazi#german history#war#second world war#battle#soldier#general#erwin rommel#allies#germany#afrikacorps#statues#culture#society#history#military#military history

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SS-Obergruppenführer & General of the SS Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich, 1942 by Walter Frentz. https://www.instagram.com/p/CJV520-JqXj/?igshid=bb991xhasc0y

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

• 1st SS Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler

The 1st SS Panzer Division "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler", short LSSAH, began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard, responsible for guarding the Führer's person, offices, and residences. Initially the size of a regiment, the LSSAH eventually grew into an elite division-sized unit during World War II.

In the early days of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), the leadership realized that a bodyguard unit composed of reliable men was needed. Adolf Hitler in early 1923, ordered the formation of a small separate bodyguard dedicated to his service rather than "a suspect mass", such as the the Sturmabteilung (SA) under Ernst Röhm. Originally the unit was composed of only eight men, commanded by Julius Schreck and Joseph Berchtold. It was designated the Stabswache (staff guard). The Stabswache were issued unique badges, but at this point was still under SA control. In May 1923, the unit was renamed Stoßtrupp (Shock Troop)–Hitler. The unit numbered no more than 20 members at that time. On November 9th, 1923, the Stoßtrupp, along with the SA and several other Nazi paramilitary units, took part in the abortive Beer Hall Putsch in Munich. In the aftermath, Hitler was imprisoned and his party and all associated formations, including the Stoßtrupp, were disbanded. Later in 1925, Hitler ordered the formation of a new bodyguard unit, the Schutzkommando (protection command). The unit was renamed the Sturmstaffel (assault squadron) and in November was renamed the Schutzstaffel, abbreviated to SS. By 1933 the SS had grown from a small bodyguard unit to a formation of over 50,000 men. The decision was made to form a new bodyguard unit, again called the Stabswache, which was mostly made up of men from the 1st SS-Standarte. By 1933 this unit was placed under the command of Sepp Dietrich, who selected 117 men to form the SS-Stabswache Berlin on March 17th, 1933. The unit replaced the army guards at the Reich Chancellery.

Out of this initial group, three eventually became divisional commanders, at least eight would become regimental commanders, fifteen became battalion commanders, and over thirty became company commanders in the Waffen-SS. Later in 1933, two further training units were formed: SS-Sonderkommando Zossen on 10 May, and a second unit, designated SS-Sonderkommando Jüterbog in July. These were the only SS units to receive military training at that time. Most of the training staff came from the ranks of the army. On September 3rd, 1933 the two Sonderkommando merged into the SS-Sonderkommando Berlin under Dietrich's command. Most of their duties involved providing outer security for Hitler at his residences, public appearances and guard duty at the Reich Chancellery. In November 1933, on the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the Sonderkommando took part in the rally and memorial service for the NSDAP members who had been killed during the putsch. During the ceremony, the members of the Sonderkommando swore personal allegiance to Hitler. At the conclusion the unit received the new title, "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler" (LAH). The term Leibstandarte was derived partly from Leibgarde, a somewhat archaic German translation of "Guard of Corps" or personal bodyguard of a military leader. On April 13th, 1934, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler ordered the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH) to be renamed "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler" (LSSAH). Himmler inserted the SS initials into the name to make it clear that the unit was independent from the army. Although nominally under Himmler, Dietrich was the real commander and handled day-to-day administration. Hitler ordered all SA leaders to attend a meeting at the Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiessee, near Munich. Hitler along with Sepp Dietrich and a unit from the LSSAH travelled to Bad Wiessee to personally oversee Röhm's arrest on June 30th. Later at around 17:00 hours, Dietrich received orders from Hitler for the LSSAH to form an "execution squad" and go to Stadelheim prison where certain SA leaders were being held. There in the prison courtyard, the LSSAH firing squad shot five SA generals and an SA colonel. This action succeeded in effectively decapitating the SA and removing Röhm's threat to Hitler's leadership. In recognition of their actions, both the LSSAH and the Landespolizeigruppe General Göring were expanded to regimental size and motorized. In addition, the SS became an independent organization, no longer part of the SA.

The LSSAH provided the honor guard at many of the Nuremberg Rallies, and in 1935 took part in the reoccupation of the Saarland. On June 6th, 1935, the LSSAH officially adopted a field-grey uniform to identify itself more with the army, which wore a similar uniform. The LSSAH was later in the vanguard of the march into Austria as part of the Anschluss, and in 1938 the unit took part in the occupation of the Sudetenland. By 1939, the LSSAH was a full infantry regiment with three infantry battalions, an artillery battalion, and anti-tank, reconnaissance and engineer sub-units. Soon after its involvement in the annexation of Bohemia and Moravia, the LSSAH was redesignated "Infanterie-Regiment Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (mot.)". When Hitler ordered the formation of an SS division in mid-1939, the Leibstandarte was designated to form its own unit. The Polish crisis of August 1939 put these plans on hold, and the LSSAH was ordered to join XIII. Armeekorps, a part of Army Group South, which was preparing for the attack on Poland. The Leibstandarte division's symbol was a skeleton key, in honor of its first commander, Josef "Sepp" Dietrich (Dietrich is German for skeleton key or lock pick); it was retained and modified to later serve as the symbol for I SS Panzer Corps. During the initial stages of the invasion of Poland, the LSSAH was attached to the 17.Infanterie-Division and tasked with providing flank protection for the southern pincer. The regiment was involved in several battles against Polish cavalry brigades attempting to hit the flanks of the German advance. At Pabianice, a town near Łódź, the LSSAH fought elements of the Polish 28th Infantry Division and the Wołyńska Cavalry Brigade in close combat. Throughout the campaign, the unit was notorious for burning villages. In addition, members of the LSSAH committed atrocities in numerous Polish towns, including the murder of 50 Jews in Błonie and the massacre of 200 civilians, including children, who were machine gunned in Złoczew. After the success at Pabianice, the LSSAH was sent to the area near Warsaw and attached to the 4.Panzer-Division under then Generalmajor (brigadier general) Georg-Hans Reinhardt. The unit saw action preventing encircled Polish units from escaping, and repelling several attempts by other Polish troops to break through. In spite of the swift military victory over Poland, the regular army had reservations about the performance of the LSSAH due to their higher casualty rate than the army units.

In early 1940 the LSSAH was expanded into a full independent motorized infantry regiment and a Sturmgeschütz (Assault Gun) battery was added to their establishment. The regiment was shifted to the Dutch border for the launch of Fall Gelb. It was to form the vanguard of the ground advance into the Netherlands, tasked with capturing a vital bridge over the IJssel, attacking the main line of defense at the Grebbeberg (the Grebbeline), and linking up with the Fallschirmjäger of Generaloberst Kurt Student's airborne forces, the 7.Flieger-Division. On May 10th, 1940 the LSSAH crossed the Dutch border, covered over 75 kilometres (47 mi), and secured a crossing over the IJssel near Zutphen after discovering that their target bridge had been destroyed. Over the next four days, the LSSAH covered over 215 kilometres (134 mi), and upon entering Rotterdam, several of its soldiers accidentally shot at and seriously wounded General Student. After the surrender of Rotterdam, the LSSAH left for the Hague, which they reached on May 15th, after capturing 3,500 Dutch soldiers as prisoners of war. After the surrender of the Netherlands on May 15th, the regiment was then moved south to France. After the British counterattack at Arras, the LSSAH, along with the SS-Verfügungs-Division, were moved to hold the perimeter around Dunkirk and reduce the size of the pocket containing the encircled British Expeditionary Force and French forces. The LSSAH took up a position 15 miles south west of Dunkirk along the line of the Aa Canal, facing the Allied defensive line near Watten. However, on the following day of May 25th, in defiance of Hitler's orders, Dietrich ordered his 3rd battalion to cross the canal and take the Wattenberg Heights beyond, where British artillery observers were putting the regiment at risk. They assaulted the heights and drove the observers off. Instead of being censured for his act of defiance, Dietrich was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. On May 26th the German advance resumed. By the 28th the LSSAH had taken the village of Wormhout, only ten miles from Dunkirk. After their surrender, soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, along with some other units (including French soldiers) were taken to a barn in La Plaine au Bois near Wormhout and Esquelbecq. It was there that troops of the LSSAH 2nd battalion, under the command of SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilhelm Mohnke committed the Wormhoudt massacre, where 80 British and French prisoners of war were killed. After the conclusion of the Western campaign on June 22nd, 1940, the LSSAH spent six months in Metz (Moselle). It was expanded to brigade size (6,500 men). A 'Flak battalion' and a StuG Batterie were among the units added to the LSSAH. A new flag was presented by Heinrich Himmler in September 1940.

During the later months of 1940, the regiment trained in amphibious assaults on the Moselle River in preparation for Operation Seelöwe, the invasion of England. After the Luftwaffe's failure in the Battle of Britain and the cancellation of the planned invasion, the LSSAH was shifted to Bulgaria in February 1941 in preparation for Operation Marita, part of the planned invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia. The operation was launched on April 6th, 1941 by aerial bombings of central-southern Yugoslavia, specially over Belgrade causing enormous destructions and thousands of victims and woundeds. After the LSSAH entered on April 12th into the Yugoslavian capital, then to follow the route of the 9.Panzer-Division. The LSSAH crossed the border near Bitola and was soon deep in Greek territory. The LSSAH captured Vevi on April 10th. LSSAH was tasked with clearing resistance from the Kleisoura Pass south-west of Vevi and driving through to the Kastoria area to cut off retreating Greek and British Commonwealth forces. The brigade participated in the clearing the Klidi Pass just south of Vevi, which was defended by a "scratch force" of Greek, Australian, British and New Zealand troops. With the fall of the two passes the main line of resistance of the Greek Epirus army was broken, and the campaign became a battle to prevent the escape of the enemy. On April 20th, following a pitched battle in the 5,000-foot-high (1,500 m) Metsovon Pass in the Pindus Mountains, the commander of the Greek Epirus army surrendered the entire force to Dietrich. By April 30th, the last British Commonwealth troops had either been captured or escaped. The LSSAH occupied a position of honor in the victory parade through Athens. After Operation Marita, the LSSAH was ordered north to join the forces of Army Group South massing for the launch of Operation Barbarossa.

Following LSSAH's outstanding performance during Marita, Himmler ordered that it should be upgraded to divisional status. The regiment, already the size of a reinforced brigade, was to be given motorized transport and redesignated "SS-Division (mot.) Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler". It was moved to Czechoslovakia in mid May for reorganization until being ordered to assemble in Poland for Operation Barbarossa, as part of Gerd von Rundstedt's, Army Group South. There was not enough time to deliver all its equipment and refit it to full divisional status before the launch of the invasion of the Soviet Union, so the new "division" remained the size of a reinforced brigade, even though its expansion and development was of concern. Through July it was attached to III Panzer Corps before finishing August as part of XLVIII Panzer Corps. During this time, the LSSAH was involved in the Battle of Uman and the subsequent capture of Kiev. In early September, the division was shifted to LIV Army Corps, as part of the 11th Army, during the advance east after the fall of Kiev. Hoping to capitalize on the collapse of the Red Army defense on the Dnepr River the reconnaissance battalion of LSSAH was tasked with making a speedy advance to capture the strategically vital choke point of the Perekop Isthmus but were rebuffed by entrenched defenders at the town of Perekop. In October, the LSSAH was transferred back north to help solidify the Axis line against fresh Soviet attacks against the Romanian 3rd Army and later took part in the heavy fighting for the city of Rostov-on-Don, which was captured in late November; there, the LSSAH took over 10,000 Red Army prisoners. However by the end of the year, the German advance faltered as Soviet resistance grew stronger. Under pressure from heavy Soviet counterattacks during the winter, the LSSAH and Army Group South retreated from Rostov to defensive lines on the river Mius.[47] After the spring rasputitsa (seasonal mud) had cleared, the division joined in Fall Blau, participating in the fighting to retake Rostov-on-Don, which fell in late July 1942. Severely understrength, the LSSAH was transferred to the Normandy region of occupied France to join the newly formed SS Panzer Corps and to be reformed as a Panzergrenadier division. The LSSAH spent the remainder of 1942 refitting as a panzergrenadier division.