#separate skill sets with different methods and reasons for existing that sometimes overlap in their use

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yes. This. We tend to associate tailoring with men because when it became popular in fashion, it was seen as more prestigious and required more skills than plain sewing. So men were more likely to dominate the market. But there have always been women tailors, just like there’s always been women who embroidered and knit and made lace for a living. (Interestingly, by the time corsets rolled around, they were more likely to be made by men than women, though women still did that work, too. It takes a lot of hand strength to get a needle through that many layers of fabric.)

The “tailoring revolution” of the 1300s (in Europe, not sure if or when a similar thing happened independently in other parts of the world but would love to hear about it if any of y’all know) refers to the time when the wealthy started to wear garments that were more than just rectangles with occasional shaping for the sleeves. As it progresses we see things like fully formed sleeve heads, shaped dress panels that incorporate godets and gores directly into the pieces, jackets/doublets etc with multiple shaped panel pieces, and so on. This was a blatant display of wealth: fabric was extremely expensive, so using these techniques (which result in a lot of fabric waste, even when piecing) was a way to signal how much money you could afford to waste on your clothes.

While these patterns were still draped in the early part of the revolution - we have wardrobe accounts of various monarchs buying X ells of muslin fabric to drape gowns for them and their family - by the 1500s we start to see the emergence of flat patterning. I believe the earliest evidence we have of this is from a 1580 Spanish tailoring manual that describes how to draft various garments (The Modern Maker has done a lot of work translating the system and laying it out for a modern audience).

From what I can tell, this is where tailoring and dressmaking started to really diverge. (I could be wrong about this part of the timeline, my wheelhouse is pretty solidly pre-1500 unless I get stuck in a hyperfocus.) And then mantua makers came along doing a different thing again - there were some pitched battles over whether they needed their own guild or if they were taking work away from the dressmakers and tailors, so it’s reasonably well documented.

Somehow there are still way too many people who think a tailor is someone who makes clothes for men (or worse, just a male clothing-maker). Tailoring is a specific trade with a specific set of techniques—historically, the difference has less to do with gender than it does to do with flat-drafting vs. draping methods of pattern-making and fitting. Tailor is not the male version of seamstress, it is gender-neutral and it refers to its own history (and seamstressing/mantua making is ALSO a trade with its own techniques and history fwiw)

#sewing#fashion history#it feels a lot like the conflation of quilting and patchwork tbh#separate skill sets with different methods and reasons for existing that sometimes overlap in their use

620 notes

·

View notes

Text

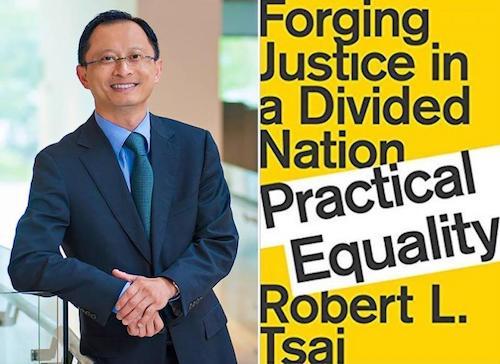

A Mighty Fine Aspiration: An Interview with Robert L. Tsai

Robert L. Tsai, a Professor of Law at American University, graciously took the time last week to answer questions regarding his new book Practical Equality. Between his busy schedule of TV appearances and book talks, I am grateful for the kindness he showed in answering my questions. Before we get to those, I want to tell you a bit about how reading his book made me feel.

Since graduating from college, I have been burying my head in fiction like an ostrich, giving my brain a rest from brain-stretching academia. Reading Practical Equality reminded me not only how much I love to learn but also how important understanding your country’s legal system is. I had so many “so that’s why this happens!” or “so that’s what that was all about!” moments while reading his book.

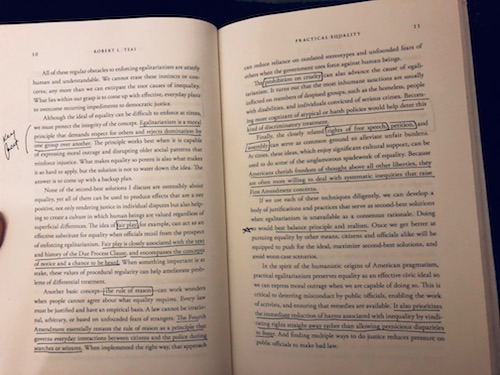

Boxing key concepts in the introduction

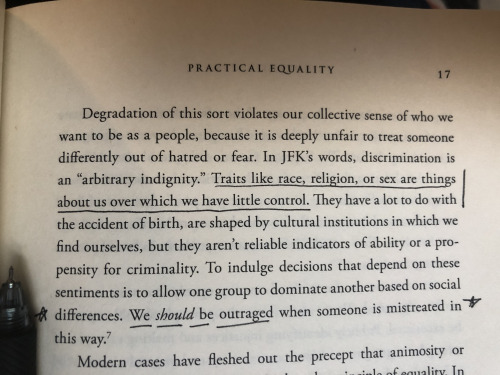

With a pen in hand, I annotated the first half of the book to track my reactions, important passages I wanted to return to, or questions I had about the material. I remembered that note-taking skills were life skills. Needless to say, I had fun being a student again. The reading experience was enlightening and incredible.

Practical Equality goes over court cases aimed at equality, and how historically arguments alternative to equality have won civil and human rights cases. As Tsai said in one of his answers, “That’s a mighty fine aspiration, but in reality it’s a very hard promise to keep.” No matter what side of the political line you fall on, Tsai tries to appeal towards all readers dissatisfied with the status of social politics through facts and circumstances.

The most exciting aspect about this book is its scope: while he shares aspirations of a truly equal society, he integrates historical, social, and political contexts into his accounts of various court cases or social issues. He doesn’t shy away from hard-to-swallow pills, but he doesn’t cast anyone as a villain. His easygoing yet knowledgeable tone taught me more about myself through my reactions to the facts.

I found his insight invaluable, hence the hefty set of interview questions below...

Island Books: You use the word egalitarian frequently throughout the book. What does an egalitarian society look like to you? How far are we in America from that ideal?

Robert Tsai: For me personally, an egalitarian society is one that takes seriously the promise that each person living in that society is worthy of being treated with respect. That’s a mighty fine aspiration, but in reality it’s a very hard promise to keep. Some think that all we need to care about is political equality: a handful of rights that are closely associated with citizenship like the vote. Others think that we only need to care about equality among citizens but can mistreat non-citizens whose labor we extract to maintain the American lifestyle. I believe in a certain amount of reciprocity, so even non-citizens who contribute to our society deserve to be treated with respect. I also think that people who commit crimes don’t give up their basic humanity, and, while they are in prison, and especially when they’ve done their time, certain kinds of conditions shouldn’t follow them forever. In my book I spend some time thinking about felon disenfranchisement, which is an abomination in a democratic society like ours.

"The key is the social meaning of an act, not merely how the action is intended but also how it is received.” - Tsai on discriminatory laws.

IB: While you show that there is a way to communicate between conservative and liberal political agents without talking about social morals, you make clear which side of the moral and political argument you fall. Have you received political, social, or general backlash for your book?

RT: I haven’t yet received any backlash for anything I’ve written about the book, but I expect that not everyone will agree with what I have to say! I do hope they give the book a try, though, since I wrote it with an eye toward appealing to a broad cross-section of readers who might not always agree with where we are in terms of social progress. I think that’s a broader lesson when it comes to struggles over equality. We do have to take sides, and that will naturally cause social friction. Sometimes, though, we can shift our arguments slightly and find a more receptive audience. And history has shown that you can’t expect to get everyone on your side, but you do need to convince a handful of people to come your way, especially those in power, if you want to help the most vulnerable in society.

IB: In Practical Equality, you utilize terms such as “fair play," “reason,” etc... in place of the word “equality” to persuade judges to see your argument for equality. Why do you think it is difficult for people to understand that “equality” and “fair play” are one in the same? Do you think that eventually judges will catch on to this as a tactic for helping them understand the importance of equality? If so, do you expect backlash or open arms?

RT: A lot of the alternative arguments I talk about in the book already share some commonalities with the traditional idea of equality. They’re also all deeply rooted ideas in our political and legal culture. But each of them has a slightly different structure and appeals to progressive and conservatives a bit differently. It’s not that these arguments lack morality, but they might emphasize a different kind of morality (for instance, fairness arguments stress procedural morality). One thing I want to point out is that although many of the historical examples in the book are in the courts, a number of my examples are out-of-court battles over equality. And my broader argument is that these arguments can be made to judges, but also to other people who have outsized influence over our lives: principals, teachers, mayors, city council members, legislators, governors. The point I try to make is that you have to build coalitions if you want to get anything done about inequality, but they don’t always have to be massive endeavors. On a three-judge panel, you have to get one judge to slide over and join a progressive judge (if there is one). On today’s very conservative U.S. Supreme Court, you need to convince Chief Justice Roberts, who is already an institutional and social conservative, to join the liberals. At the state level, you might need only convince an attorney general or governor about the righteousness of your cause and, say in the criminal context, a great deal of inequality could be ameliorated that way.

The location of the final say on many of the cases Tsai discusses in his book.

IB: When I first started your book, I wondered if pursuing these other arguments for the sake of justice would be putting aside the work of equality. Though we were still holding to its message, the idea of equality and the moral ground would be left out of the media and the judges’ responses. Many people feel as though the system of justice is not successful unless the offenders are told that they were wrong. How would respond to someone who argued that your book was not doing the moral work of equality?

RT: I try to make clear that accepting my argument about how to do practical equality doesn’t mean giving up one’s closely held moral views about who deserves equality. It doesn’t mean that we should stop arguing, for instance, that people who don’t look like us deserve to be treated like full moral beings like the rest of us. It just means that you need to recognize that conflicts will arise, and that you can’t convince everyone, or even most people, to adopt your moral view of things. I say that we should look into alternative arguments as backups, so we can reduce the suffering of vulnerable segments of society whenever we can, while we continue to have our important moral arguments.

IB: What do you see as the most common method from your book for dealing with justice?

RT: At the moment, arguments about fairness and avoiding cruelty are capable of doing tremendous work. And as I say, sometimes these arguments can help reduce existing inequities even though we aren’t talking about equality in a full-throated sense. These ideas overlap with equality and can have broad appeal even when people disagree over who deserves to be treated equally. Right now, we are going through a trying time as refugees and visitors from Hispanic and Muslim countries are being treated unequally by the Trump administration. We might not all agree in a deep sense that foreigners should be treated exactly the same as U.S. citizens, but many of us think that these populations should be treated fairly, and that abusive conditions must be avoided. The administration is dealing with different migrants and refugees differently, it has separated migrant children from parents, and even plans to speed up asylum applications and deportations. These arguments can do some good in reducing disparities in how people are treated.

To learn more about Robert L. Tsai and his research, join us Friday, March 8th at 6:00pm for a Mercer Island Democratic Association. He will discuss his book and have a Q&A session about the his research and the current state of affairs in America and the world.

-Kelleen

#robert l. tsai#robert tsai#american university#politcs#political literature#island books#interview#kelleen#kelleen cummings#MIDA

0 notes

Text

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media?: Sometimes I wonder how I'm still allowed to write a regular column on social media, never mind that it seems to be reasonably popular. I'm unlikely to ever write about Snapchat, for example, partly because I still can't get my head around the platform, but mainly because focusing on the technical minutiae of specific tools seems irrelevant. It's like discussing the art of the novel by analyzing the brand of typewriter George Orwell used. I don't even like the term “social media” because it defines what we do by the tools with which we do it. Therefore, any discussion of social media can't help but emphasize the role of the typewriter while reducing the importance of the writer and his craft. And then there's the buzzwordy-ness of the phrase. You're more likely to hear it thrown about marketing departments, newsrooms, and tech start-ups than *ahem* normal conversation. My wife doesn't “share to social media;” she puts photos of our cats on Facebook. My daughter doesn't “update social media;” she chats with her friends. Whatever they're doing, the particular channel is largely irrelevant. If Facebook disappeared tomorrow, it would probably only slow down the cat photos and gossip for five minutes before they switched to alternative methods to continue the same behavior. Of course they're both aware of social media as a concept, but I don't think I've ever heard them use the phrase to describe what they're doing. (At this point in the original draft, my adorable editor commented that the only other time she hears parents using the term is to attack the concept. “Protect our children from the dangers of social media,” they write, completely missing the irony of discussing their concern on Mumsnet talk boards. Just like previous concerns about rock ‘n' roll [enjoying music], horror comics [pulp fiction], and video gaming [ummm … playing games], social media becomes a lazy categorization for what other people do, completely blind to the overlaps with our own normalized behavior.) What is uniquely social about Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn – and the hundreds of other platforms that somehow qualify for the label – that isn't true for just about any other form of media, digital or otherwise? Crikey, the telephone, letter writing, even prehistoric cave paintings are all media intended to communicate ideas and enable social interactions between two or more people. As my editor's comment shows, we often end up using tracked changes and comments within Word documents to communicate and collaborate on the final version of an article. Even Microsoft Word can be a digital social medium. Sure, that's a private social interaction between two people collaborating on a single document, whereas discussions of social media often emphasize the more public, broadcast nature of the tools. Yet Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, and Twitter DMs are most commonly used for private interactions within small groups, often only two people. Meanwhile, a Google Doc can have as many as 200 collaborators and can be made public once published. Group size and whether something is public or private are far less important to understanding social media than you might think. We need to look elsewhere. Creating the buzzword There are at least three accounts of who first coined the phrase “social media” and how it came to be. As one of these explanations hinges on little more than someone being first to register the domain name, we'll skip to the other two claims, which are far more revealing. According to then-AOL executive Ted Leonsis, the phrase was in use internally at AOL in the early 1990s. However, the first recorded use of the term is 1997 when Leonsis discussed providing internet users with “social media, places where they can be entertained, communicate, and participate in a social environment.” Writer and researcher Darrell Berry maintains that he coined the term in 1994 while developing an online media environment called Matisse. In a 1995 paper called Social Media Spaces, Berry argued that the internet shouldn't just be an archive of static pages, but a network for users to connect, engage, and interact with each other. Who said it first matters less than what both tried to articulate. Neither describes definitive features – certainly not in the way most people think of social media. Leonsis' idea of online places to communicate and participate could just as easily describe the comments thread on a blog, the reviews on Amazon, or even your webmail inbox, yet these are rarely included in discussions of social media today. And Berry's vision of the internet as one socially interactive network makes our modern usage of “social media” seem ridiculously parochial. HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: Do You Operate in a Social Media Bubble? 3 Questions to Ask Social media is … what exactly? Social media has featured in many court cases over the years, and if there's one place that will not tolerate a vague, undefined concept, it's a courtroom. Therefore, many lawyers have attempted to come up with a satisfactory legal definition of social media. In 2012, the California legislature settled on this gem of precision … “social media” means an electronic service or account, or electronic content, including, but not limited to, videos, still photographs, blogs, video blogs, podcasts, instant and text messages, email, online services or accounts, or Internet Web site profiles or locations. The California legislature found it impossible to delineate between social media and every other form of digital or electronic media, online and off. By this definition, someone could legally argue those private and *ahem* “artistic” photographs stored on a celebrity's smartphone are social media. California isn't alone. Every other social media policy or legal definition I have investigated is similarly broad, open-ended, and extremely unhelpful. In fact, the social media guidelines of the Australian Communications and Media Authority hedges further by stating, “Social media also includes all other emerging electronic/digital communication applications.” Way to cover your ass there. There is no unique characteristic, feature or defining trait – or even a combination of such. Every #socialmedia policy or legal definition I have investigated is broad, open-ended & unhelpful. @kimotaClick To Tweet Social media as an idea, as a concept, clearly exists – if only subjectively. Your idea of social media may differ in small or large ways from mine. But social media as a thing, as something knowable that exists in the concrete rather than the abstract, is nothing more than a myth. It's a mirage. And when you believe a mirage is real, bad things can happen. Why this matters By treating social media as somehow different (albeit, undefinably so) we fall into the trap of “social media exceptionalism.” If social media is supposedly unique or otherwise distinct from other media, then all previous rules and practices don't apply. Its special nature requires us to develop new regulations, create separate workflows, and focus on different metrics. How often have you heard or read someone argue that social media can't be held accountable or measured in the same way as other marketing activities? Exactly. Some have exploited this exceptionalism by popularizing the idea that social media marketing is a kind of alchemy, beyond the ken of mere mortals. Only they can exploit the secret algorithm or access every obscure feature. So you invite in the social media shaman to utter strange incantations about engagement, ranking factors, and influence, reinforcing the magical otherness of these tools. This belief that certain technologies and platforms are inherently social while others are not reinforces the flawed notion that social interaction is a product of the tool and not the person using it. This risk absolves us of taking responsibility for our own creativity, civility, and communication skills. Why bother if just by sharing an unimaginative branded meme or self-serving article to social it somehow magically becomes social content? The flawed notion is that social interaction is a product of the tool & not the person using it. @kimotaClick To Tweet Just as buying a typewriter doesn't make you a novelist, setting up a Facebook page doesn't imbue you with professional social skills. They are still your responsibility. Ultimately, your skills as a communicator – your way with words, your empathy, your willingness to interact – are what should define your use of a medium, any medium, as truly social. Your way w/ words, empathy, & interaction are what should define use of a medium as truly social. @kimotaClick To Tweet And then what use would we have for a phrase like “social media”? HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: The Art and Science of Emotional Engagement A version of this article originally appeared in the April issue of Chief Content Officer. Sign up to receive your free subscription to our bimonthly, print magazine. Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute The post Is it Time to Abolish Social Media? appeared first on Content Marketing Institute. http://bit.ly/2qCxQRv

0 notes

Text

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media?

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media?

Sometimes I wonder how I’m still allowed to write a regular column on social media, never mind that it seems to be reasonably popular. I’m unlikely to ever write about Snapchat, for example, partly because I still can’t get my head around the platform, but mainly because focusing on the technical minutiae of specific tools seems irrelevant. It’s like discussing the art of the novel by analyzing the brand of typewriter George Orwell used.

I don’t even like the term “social media” because it defines what we do by the tools with which we do it. Therefore, any discussion of social media can’t help but emphasize the role of the typewriter while reducing the importance of the writer and his craft.

And then there’s the buzzwordy-ness of the phrase. You’re more likely to hear it thrown about marketing departments, newsrooms, and tech start-ups than *ahem* normal conversation. My wife doesn’t “share to social media;” she puts photos of our cats on Facebook. My daughter doesn’t “update social media;” she chats with her friends. Whatever they’re doing, the particular channel is largely irrelevant. If Facebook disappeared tomorrow, it would probably only slow down the cat photos and gossip for five minutes before they switched to alternative methods to continue the same behavior.

Of course they’re both aware of social media as a concept, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard them use the phrase to describe what they’re doing.

(At this point in the original draft, my adorable editor commented that the only other time she hears parents using the term is to attack the concept. “Protect our children from the dangers of social media,” they write, completely missing the irony of discussing their concern on Mumsnet talk boards. Just like previous concerns about rock ‘n’ roll [enjoying music], horror comics [pulp fiction], and video gaming [ummm … playing games], social media becomes a lazy categorization for what other people do, completely blind to the overlaps with our own normalized behavior.)

What is uniquely social about Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn – and the hundreds of other platforms that somehow qualify for the label – that isn’t true for just about any other form of media, digital or otherwise? Crikey, the telephone, letter writing, even prehistoric cave paintings are all media intended to communicate ideas and enable social interactions between two or more people.

As my editor’s comment shows, we often end up using tracked changes and comments within Word documents to communicate and collaborate on the final version of an article. Even Microsoft Word can be a digital social medium.

Sure, that’s a private social interaction between two people collaborating on a single document, whereas discussions of social media often emphasize the more public, broadcast nature of the tools. Yet Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, and Twitter DMs are most commonly used for private interactions within small groups, often only two people. Meanwhile, a Google Doc can have as many as 200 collaborators and can be made public once published. Group size and whether something is public or private are far less important to understanding social media than you might think. We need to look elsewhere.

Creating the buzzword

There are at least three accounts of who first coined the phrase “social media” and how it came to be. As one of these explanations hinges on little more than someone being first to register the domain name, we’ll skip to the other two claims, which are far more revealing.

According to then-AOL executive Ted Leonsis, the phrase was in use internally at AOL in the early 1990s. However, the first recorded use of the term is 1997 when Leonsis discussed providing internet users with “social media, places where they can be entertained, communicate, and participate in a social environment.”

Writer and researcher Darrell Berry maintains that he coined the term in 1994 while developing an online media environment called Matisse. In a 1995 paper called Social Media Spaces, Berry argued that the internet shouldn’t just be an archive of static pages, but a network for users to connect, engage, and interact with each other.

Who said it first matters less than what both tried to articulate. Neither describes definitive features – certainly not in the way most people think of social media. Leonsis’ idea of online places to communicate and participate could just as easily describe the comments thread on a blog, the reviews on Amazon, or even your webmail inbox, yet these are rarely included in discussions of social media today. And Berry’s vision of the internet as one socially interactive network makes our modern usage of “social media” seem ridiculously parochial.

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: Do You Operate in a Social Media Bubble? 3 Questions to Ask

Social media is … what exactly?

Social media has featured in many court cases over the years, and if there’s one place that will not tolerate a vague, undefined concept, it’s a courtroom. Therefore, many lawyers have attempted to come up with a satisfactory legal definition of social media. In 2012, the California legislature settled on this gem of precision …

“social media” means an electronic service or account, or electronic content, including, but not limited to, videos, still photographs, blogs, video blogs, podcasts, instant and text messages, email, online services or accounts, or Internet Web site profiles or locations.

The California legislature found it impossible to delineate between social media and every other form of digital or electronic media, online and off. By this definition, someone could legally argue those private and *ahem* “artistic” photographs stored on a celebrity’s smartphone are social media.

California isn’t alone. Every other social media policy or legal definition I have investigated is similarly broad, open-ended, and extremely unhelpful. In fact, the social media guidelines of the Australian Communications and Media Authority hedges further by stating, “Social media also includes all other emerging electronic/digital communication applications.” Way to cover your ass there. There is no unique characteristic, feature or defining trait – or even a combination of such.

Every #socialmedia policy or legal definition I have investigated is broad, open-ended & unhelpful. @kimota Click To Tweet

Social media as an idea, as a concept, clearly exists – if only subjectively. Your idea of social media may differ in small or large ways from mine. But social media as a thing, as something knowable that exists in the concrete rather than the abstract, is nothing more than a myth. It’s a mirage.

And when you believe a mirage is real, bad things can happen.

Why this matters

By treating social media as somehow different (albeit, undefinably so) we fall into the trap of “social media exceptionalism.” If social media is supposedly unique or otherwise distinct from other media, then all previous rules and practices don’t apply. Its special nature requires us to develop new regulations, create separate workflows, and focus on different metrics. How often have you heard or read someone argue that social media can’t be held accountable or measured in the same way as other marketing activities? Exactly.

Some have exploited this exceptionalism by popularizing the idea that social media marketing is a kind of alchemy, beyond the ken of mere mortals. Only they can exploit the secret algorithm or access every obscure feature. So you invite in the social media shaman to utter strange incantations about engagement, ranking factors, and influence, reinforcing the magical otherness of these tools.

This belief that certain technologies and platforms are inherently social while others are not reinforces the flawed notion that social interaction is a product of the tool and not the person using it. This risk absolves us of taking responsibility for our own creativity, civility, and communication skills. Why bother if just by sharing an unimaginative branded meme or self-serving article to social it somehow magically becomes social content?

The flawed notion is that social interaction is a product of the tool & not the person using it. @kimota Click To Tweet

Just as buying a typewriter doesn’t make you a novelist, setting up a Facebook page doesn’t imbue you with professional social skills. They are still your responsibility. Ultimately, your skills as a communicator – your way with words, your empathy, your willingness to interact – are what should define your use of a medium, any medium, as truly social.

Your way w/ words, empathy, & interaction are what should define use of a medium as truly social. @kimota Click To Tweet

And then what use would we have for a phrase like “social media”?

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: The Art and Science of Emotional Engagement

A version of this article originally appeared in the April issue of Chief Content Officer. Sign up to receive your free subscription to our bimonthly, print magazine.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute

The post Is it Time to Abolish Social Media? appeared first on Content Marketing Institute.

0 notes

Text

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media?

Sometimes I wonder how I’m still allowed to write a regular column on social media, never mind that it seems to be reasonably popular. I’m unlikely to ever write about Snapchat, for example, partly because I still can’t get my head around the platform, but mainly because focusing on the technical minutiae of specific tools seems irrelevant. It’s like discussing the art of the novel by analyzing the brand of typewriter George Orwell used.

I don’t even like the term “social media” because it defines what we do by the tools with which we do it. Therefore, any discussion of social media can’t help but emphasize the role of the typewriter while reducing the importance of the writer and his craft.

And then there’s the buzzwordy-ness of the phrase. You’re more likely to hear it thrown about marketing departments, newsrooms, and tech start-ups than *ahem* normal conversation. My wife doesn’t “share to social media;” she puts photos of our cats on Facebook. My daughter doesn’t “update social media;” she chats with her friends. Whatever they’re doing, the particular channel is largely irrelevant. If Facebook disappeared tomorrow, it would probably only slow down the cat photos and gossip for five minutes before they switched to alternative methods to continue the same behavior.

Of course they’re both aware of social media as a concept, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard them use the phrase to describe what they’re doing.

(At this point in the original draft, my adorable editor commented that the only other time she hears parents using the term is to attack the concept. “Protect our children from the dangers of social media,” they write, completely missing the irony of discussing their concern on Mumsnet talk boards. Just like previous concerns about rock ‘n’ roll [enjoying music], horror comics [pulp fiction], and video gaming [ummm … playing games], social media becomes a lazy categorization for what other people do, completely blind to the overlaps with our own normalized behavior.)

What is uniquely social about Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn – and the hundreds of other platforms that somehow qualify for the label – that isn’t true for just about any other form of media, digital or otherwise? Crikey, the telephone, letter writing, even prehistoric cave paintings are all media intended to communicate ideas and enable social interactions between two or more people.

As my editor’s comment shows, we often end up using tracked changes and comments within Word documents to communicate and collaborate on the final version of an article. Even Microsoft Word can be a digital social medium.

Sure, that’s a private social interaction between two people collaborating on a single document, whereas discussions of social media often emphasize the more public, broadcast nature of the tools. Yet Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, and Twitter DMs are most commonly used for private interactions within small groups, often only two people. Meanwhile, a Google Doc can have as many as 200 collaborators and can be made public once published. Group size and whether something is public or private are far less important to understanding social media than you might think. We need to look elsewhere.

Creating the buzzword

There are at least three accounts of who first coined the phrase “social media” and how it came to be. As one of these explanations hinges on little more than someone being first to register the domain name, we’ll skip to the other two claims, which are far more revealing.

According to then-AOL executive Ted Leonsis, the phrase was in use internally at AOL in the early 1990s. However, the first recorded use of the term is 1997 when Leonsis discussed providing internet users with “social media, places where they can be entertained, communicate, and participate in a social environment.”

Writer and researcher Darrell Berry maintains that he coined the term in 1994 while developing an online media environment called Matisse. In a 1995 paper called Social Media Spaces, Berry argued that the internet shouldn’t just be an archive of static pages, but a network for users to connect, engage, and interact with each other.

Who said it first matters less than what both tried to articulate. Neither describes definitive features – certainly not in the way most people think of social media. Leonsis’ idea of online places to communicate and participate could just as easily describe the comments thread on a blog, the reviews on Amazon, or even your webmail inbox, yet these are rarely included in discussions of social media today. And Berry’s vision of the internet as one socially interactive network makes our modern usage of “social media” seem ridiculously parochial.

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: Do You Operate in a Social Media Bubble? 3 Questions to Ask

Social media is … what exactly?

Social media has featured in many court cases over the years, and if there’s one place that will not tolerate a vague, undefined concept, it’s a courtroom. Therefore, many lawyers have attempted to come up with a satisfactory legal definition of social media. In 2012, the California legislature settled on this gem of precision …

“social media” means an electronic service or account, or electronic content, including, but not limited to, videos, still photographs, blogs, video blogs, podcasts, instant and text messages, email, online services or accounts, or Internet Web site profiles or locations.

The California legislature found it impossible to delineate between social media and every other form of digital or electronic media, online and off. By this definition, someone could legally argue those private and *ahem* “artistic” photographs stored on a celebrity’s smartphone are social media.

California isn’t alone. Every other social media policy or legal definition I have investigated is similarly broad, open-ended, and extremely unhelpful. In fact, the social media guidelines of the Australian Communications and Media Authority hedges further by stating, “Social media also includes all other emerging electronic/digital communication applications.” Way to cover your ass there. There is no unique characteristic, feature or defining trait – or even a combination of such.

Every #socialmedia policy or legal definition I have investigated is broad, open-ended & unhelpful. @kimota Click To Tweet

Social media as an idea, as a concept, clearly exists – if only subjectively. Your idea of social media may differ in small or large ways from mine. But social media as a thing, as something knowable that exists in the concrete rather than the abstract, is nothing more than a myth. It’s a mirage.

And when you believe a mirage is real, bad things can happen.

Why this matters

By treating social media as somehow different (albeit, undefinably so) we fall into the trap of “social media exceptionalism.” If social media is supposedly unique or otherwise distinct from other media, then all previous rules and practices don’t apply. Its special nature requires us to develop new regulations, create separate workflows, and focus on different metrics. How often have you heard or read someone argue that social media can’t be held accountable or measured in the same way as other marketing activities? Exactly.

Some have exploited this exceptionalism by popularizing the idea that social media marketing is a kind of alchemy, beyond the ken of mere mortals. Only they can exploit the secret algorithm or access every obscure feature. So you invite in the social media shaman to utter strange incantations about engagement, ranking factors, and influence, reinforcing the magical otherness of these tools.

This belief that certain technologies and platforms are inherently social while others are not reinforces the flawed notion that social interaction is a product of the tool and not the person using it. This risk absolves us of taking responsibility for our own creativity, civility, and communication skills. Why bother if just by sharing an unimaginative branded meme or self-serving article to social it somehow magically becomes social content?

The flawed notion is that social interaction is a product of the tool & not the person using it. @kimota Click To Tweet

Just as buying a typewriter doesn’t make you a novelist, setting up a Facebook page doesn’t imbue you with professional social skills. They are still your responsibility. Ultimately, your skills as a communicator – your way with words, your empathy, your willingness to interact – are what should define your use of a medium, any medium, as truly social.

Your way w/ words, empathy, & interaction are what should define use of a medium as truly social. @kimota Click To Tweet

And then what use would we have for a phrase like “social media”?

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: The Art and Science of Emotional Engagement

A version of this article originally appeared in the April issue of Chief Content Officer. Sign up to receive your free subscription to our bimonthly, print magazine.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute

The post Is it Time to Abolish Social Media? appeared first on Content Marketing Institute.

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media? syndicated from http://ift.tt/2maPRjm

0 notes

Text

Is it Time to Abolish Social Media?

Sometimes I wonder how I’m still allowed to write a regular column on social media, never mind that it seems to be reasonably popular. I’m unlikely to ever write about Snapchat, for example, partly because I still can’t get my head around the platform, but mainly because focusing on the technical minutiae of specific tools seems irrelevant. It’s like discussing the art of the novel by analyzing the brand of typewriter George Orwell used.

I don’t even like the term “social media” because it defines what we do by the tools with which we do it. Therefore, any discussion of social media can’t help but emphasize the role of the typewriter while reducing the importance of the writer and his craft.

And then there’s the buzzwordy-ness of the phrase. You’re more likely to hear it thrown about marketing departments, newsrooms, and tech start-ups than *ahem* normal conversation. My wife doesn’t “share to social media;” she puts photos of our cats on Facebook. My daughter doesn’t “update social media;” she chats with her friends. Whatever they’re doing, the particular channel is largely irrelevant. If Facebook disappeared tomorrow, it would probably only slow down the cat photos and gossip for five minutes before they switched to alternative methods to continue the same behavior.

Of course they’re both aware of social media as a concept, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard them use the phrase to describe what they’re doing.

(At this point in the original draft, my adorable editor commented that the only other time she hears parents using the term is to attack the concept. “Protect our children from the dangers of social media,” they write, completely missing the irony of discussing their concern on Mumsnet talk boards. Just like previous concerns about rock ‘n’ roll [enjoying music], horror comics [pulp fiction], and video gaming [ummm … playing games], social media becomes a lazy categorization for what other people do, completely blind to the overlaps with our own normalized behavior.)

What is uniquely social about Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn – and the hundreds of other platforms that somehow qualify for the label – that isn’t true for just about any other form of media, digital or otherwise? Crikey, the telephone, letter writing, even prehistoric cave paintings are all media intended to communicate ideas and enable social interactions between two or more people.

As my editor’s comment shows, we often end up using tracked changes and comments within Word documents to communicate and collaborate on the final version of an article. Even Microsoft Word can be a digital social medium.

Sure, that’s a private social interaction between two people collaborating on a single document, whereas discussions of social media often emphasize the more public, broadcast nature of the tools. Yet Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, and Twitter DMs are most commonly used for private interactions within small groups, often only two people. Meanwhile, a Google Doc can have as many as 200 collaborators and can be made public once published. Group size and whether something is public or private are far less important to understanding social media than you might think. We need to look elsewhere.

Creating the buzzword

There are at least three accounts of who first coined the phrase “social media” and how it came to be. As one of these explanations hinges on little more than someone being first to register the domain name, we’ll skip to the other two claims, which are far more revealing.

According to then-AOL executive Ted Leonsis, the phrase was in use internally at AOL in the early 1990s. However, the first recorded use of the term is 1997 when Leonsis discussed providing internet users with “social media, places where they can be entertained, communicate, and participate in a social environment.”

Writer and researcher Darrell Berry maintains that he coined the term in 1994 while developing an online media environment called Matisse. In a 1995 paper called Social Media Spaces, Berry argued that the internet shouldn’t just be an archive of static pages, but a network for users to connect, engage, and interact with each other.

Who said it first matters less than what both tried to articulate. Neither describes definitive features – certainly not in the way most people think of social media. Leonsis’ idea of online places to communicate and participate could just as easily describe the comments thread on a blog, the reviews on Amazon, or even your webmail inbox, yet these are rarely included in discussions of social media today. And Berry’s vision of the internet as one socially interactive network makes our modern usage of “social media” seem ridiculously parochial.

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: Do You Operate in a Social Media Bubble? 3 Questions to Ask

Social media is … what exactly?

Social media has featured in many court cases over the years, and if there’s one place that will not tolerate a vague, undefined concept, it’s a courtroom. Therefore, many lawyers have attempted to come up with a satisfactory legal definition of social media. In 2012, the California legislature settled on this gem of precision …

“social media” means an electronic service or account, or electronic content, including, but not limited to, videos, still photographs, blogs, video blogs, podcasts, instant and text messages, email, online services or accounts, or Internet Web site profiles or locations.

The California legislature found it impossible to delineate between social media and every other form of digital or electronic media, online and off. By this definition, someone could legally argue those private and *ahem* “artistic” photographs stored on a celebrity’s smartphone are social media.

California isn’t alone. Every other social media policy or legal definition I have investigated is similarly broad, open-ended, and extremely unhelpful. In fact, the social media guidelines of the Australian Communications and Media Authority hedges further by stating, “Social media also includes all other emerging electronic/digital communication applications.” Way to cover your ass there. There is no unique characteristic, feature or defining trait – or even a combination of such.

Every #socialmedia policy or legal definition I have investigated is broad, open-ended & unhelpful. @kimota Click To Tweet

Social media as an idea, as a concept, clearly exists – if only subjectively. Your idea of social media may differ in small or large ways from mine. But social media as a thing, as something knowable that exists in the concrete rather than the abstract, is nothing more than a myth. It’s a mirage.

And when you believe a mirage is real, bad things can happen.

Why this matters

By treating social media as somehow different (albeit, undefinably so) we fall into the trap of “social media exceptionalism.” If social media is supposedly unique or otherwise distinct from other media, then all previous rules and practices don’t apply. Its special nature requires us to develop new regulations, create separate workflows, and focus on different metrics. How often have you heard or read someone argue that social media can’t be held accountable or measured in the same way as other marketing activities? Exactly.

Some have exploited this exceptionalism by popularizing the idea that social media marketing is a kind of alchemy, beyond the ken of mere mortals. Only they can exploit the secret algorithm or access every obscure feature. So you invite in the social media shaman to utter strange incantations about engagement, ranking factors, and influence, reinforcing the magical otherness of these tools.

This belief that certain technologies and platforms are inherently social while others are not reinforces the flawed notion that social interaction is a product of the tool and not the person using it. This risk absolves us of taking responsibility for our own creativity, civility, and communication skills. Why bother if just by sharing an unimaginative branded meme or self-serving article to social it somehow magically becomes social content?

The flawed notion is that social interaction is a product of the tool & not the person using it. @kimota Click To Tweet

Just as buying a typewriter doesn’t make you a novelist, setting up a Facebook page doesn’t imbue you with professional social skills. They are still your responsibility. Ultimately, your skills as a communicator – your way with words, your empathy, your willingness to interact – are what should define your use of a medium, any medium, as truly social.

Your way w/ words, empathy, & interaction are what should define use of a medium as truly social. @kimota Click To Tweet

And then what use would we have for a phrase like “social media”?

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT: The Art and Science of Emotional Engagement

A version of this article originally appeared in the April issue of Chief Content Officer. Sign up to receive your free subscription to our bimonthly, print magazine.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute

The post Is it Time to Abolish Social Media? appeared first on Content Marketing Institute.

from http://contentmarketinginstitute.com/2017/05/time-abolish-social-media/

0 notes