#senegalese diaspora

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vintage African Royal Princesses Sterling Silver Clip-On Earrings by Candida - Joe Calafato South Africa

Stunning sterling silver earrings by world-renowned South African jewelry artist, Joe Calafato! Rich with vivid imagery, Calafato’s timeless African iconography and aesthetic appreciation of African expressions are once again present in this gorgeous pair of earrings that wonderfully capture the nobility of African female beauty.

These earrings are a masterfully designed portrayal of two Nubian princesses wearing a traditional majestic headdress with imperial expressions upon their faces. These beautiful earrings have a rich, natural patina and are hallmarked, are lightweight, and cling very gently on the ear with hinged clips. The clip-on earrings have an endearing and enduring sentiment for one with a keen eye for African beauty and art!

#African jewelry#African art#African beauty#African princess#African queen#Nubian princess#Nubian queen#South Africa#South African jewelry#South African#Joe Calafato#Calafato#vintage jewelry#vintage earrings#ethnic jewelry#Black pride#Afrocentric#Nigerian princess#African wedding#African heritage#African culture#African diaspora#Senegalese#etsy

1 note

·

View note

Text

my senegalese friend asking if i wanted to come with him to meet the senegalese president at this event for the diaspora next week

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Touki Bouki, 1973

"Touki Bouki," which is also known as "The Journey of the Hyena." It's a classic Senegalese film from 1973, directed by Djibril Diop Mambéty. The film tells the story of a young couple, Mory and Anta, who dream of leaving Dakar and traveling to Paris, in hopes of a better life . Along the way, they encounter a host of colourful characters and face a variety of challenges and obstacles. "Touki Bouki" is widely regarded as a masterpiece of African cinema, and it is known for its striking visual style, its innovative use of sound and music, and its powerful exploration of themes related to identity, migration, and cultural exchange. I think that "Touki Bouki" is an important and inspiring film that continues to resonate with audiences today, and it is great story for audiences who are interested in exploring the rich and vibrant history of African cinema.

I think that "Touki Bouki" is an interesting and thought-provoking film that raises important questions about identity, migration, and the African diaspora. This desire reflects a broader trend in African history, in which people have often sought to migrate to other parts of the world in search of economic opportunity, political freedom, or cultural exchange. At the same time, however," Touki Bouki" also highlights the challenges and complexities of this desire, and it raises important questions about the relationship between Africa and the African diaspora. For example, the film suggests that the desire to leave Africa and become part of the diaspora can sometimes be driven by a sense of alienation or disconnection from one's own cultural heritage. However, it also suggests that this desire can be complicated by factors such as racism, economic exploitation, and cultural misunderstanding.

Visually, "Touki Bouki" is a striking and innovative film that makes use of a variety of techniques to create a unique and memorable cinematic experience. One of the most notable features of the film is its use of surreal imagery and dreamlike sequences, which create a sense of dislocation and fragmentation that reflects the characters' own sense of alienation and displacement. In addition, I think that the film makes use of a variety of visual and auditory techniques to create a sense of rhythm and movement that is both hypnotic and engaging. For example, the film features a number of sequences that are set to music, and these sequences use a combination of sound and image to create a powerful and immersive sensory experience.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you happen to know a good book about black americans in France before WWI? Around the Belle Epoque?

i cant think off the top of my head anything specific but i like these sources taking a look at the belle epoque [sections pulled under readmore] ..if anyone has specifically what this person’s looking for id love to see

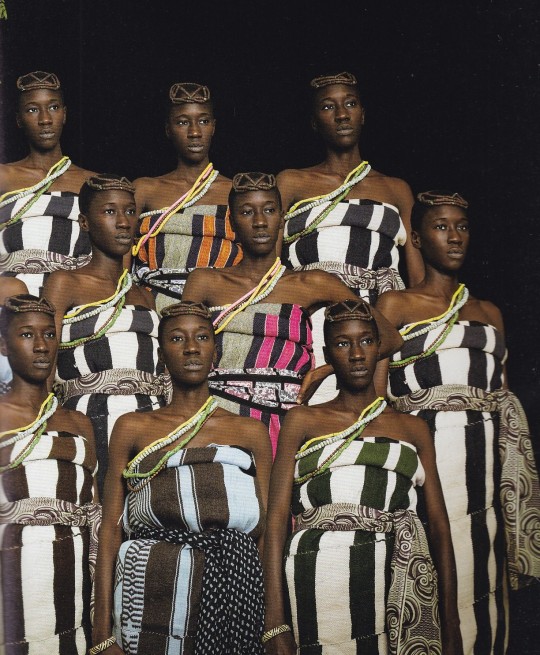

In the northern quarter of the Bois de Boulogne in February 1891, not far from the bridle paths where the fashionable women rode à l’amazone, an Englishman called John H. Hood positioned thirty-eight men and women from the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa in an animal enclosure in the zoological gardens. “Ethnographic exhibitions” were guaranteed money in the pot—crowds were always up a third, more francs clattering through the cash registers. Since one showman brought fourteen “Nubians” as foils to his wild animals in 1877, there had been Samis, Kalmuks, Araucanians, Somalis, Ashantis, and Senegalese. Their appearance was organized by the French government to pique the public’s interest in colonial expansion. The Society for Anthropology came to measure skulls and complain, in 1881, that they were not permitted to examine the genitals of the Tierra del Fuegians. In January 1891, the Nouveau Cirque’s pantomime was La Cravache (“The Whip”), featuring Chocolat [the stage name of Rafael Padilla, an Afro-Cuban man born into slavery turned famous performer in France during the Belle Epoque] as a servant arrested by a policeman who thinks he is a Somali escaped from the zoological gardens. That year, the zoo offered punters the female Dahomey soldiers, or N’Nonmiton, whom they called Amazons. “These famous warrioresses, strange and legendary, who appear to us like a fantastical vision,” enthused the pamphlet that accompanied the show, “in I know not what troubling vapors of an African mirage, are here, under our eyes, with their picturesque uniforms, their deadly weapons, their dance and their war games, their savage and valiant demeanor.” The N’Nonmiton wore long striped skirts and strings of beads that crisscrossed their torsos, and duly waved scimitars and muskets in drill, while the Parisians watched from outside the enclosure. The previous October, France had defeated Dahomey in a first colonial war. (from the second link)

This period saw the blossoming of print cultures in Africa and the African diaspora, particularly Anglophone areas, which ‘saw an explosion of writing and print, produced and circulated not only by the highly educated and publicly visible figures that dominate political histories of Africa but also by non-elites or obscure aspirants to elite status’, as the work of Karin Barber has outlined. These figures included ‘waged laborers, clerks, village headmasters, traders, and artisans’ who ‘read, wrote, and hoarded texts of many kinds’; ‘[l]ocal, small-scale print production became a part of social life’. What we observe here are not simply ‘isolated examples of the uses of literacy scattered across the continent but the history of a remarkably consistent and widespread efflorescence – a social phenomenon happening all over colonial Anglophone Africa at the same time and with comparable features’ (Barber 2006: 1–3). This flourishing of print cultures was not isolated to the continent. Following Reconstruction in the US there was an explosion in African American literacy and newspaper production: between 1865 and 1900, over 1,200 black newspapers were established (Marable 1991: 8). African American illiteracy rapidly dropped from seventy per cent in 1880 to 30.4 per cent in 1910 (Detweiler 1922: 6). During the early twentieth century, a largely bourgeois postbellum African American press gave way to an increasingly radical mass-circulation media. ‘Never before had so many African Americans purchased and read newspapers produced by and devoted to the interests of their race’, observes a study of this press. ‘Never before had the printed word had as much impact on the everyday lives of middle- and lower-class Blacks’ (Digby-Junger 1998: 263–4). The implications of this efflorescence of print for political affinity – as with the other movements of the period – are far more complex than the ‘nationalism’ allowed for in Benedict Anderson's original formulation. (from the first link)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rubell Museum - DC - Jan 13 2024

A trip to the Rubell Museum was something to look forward to despite my new Doc Martens slicing up my ankles during my 10-minute walk from the Waterfront Metro station. Opened on Oct 29th, 2022, the DC location at 65 I St. SW brought Mera and Don Rubell's collection of post-1980 art from Miami to the DC's Southwest neighborhood. This would be my second time visiting with my first experience viewing the inaugural exhibition What's Going On?. The collection showcased many artists I was not familiar with. It was a treat discovering new and exciting art. For me, artists that I wanted to learn more about from my last visit were Chase Hall, Hernan Bas and Christina Quarles.

Christina Quarles

Detail: Fell to Earth (Felt to Pieces), 2018

Acrylic on Canvas

Taking advantage of the gorgeous and expansive space past the entrance, the museum mounted works by Alexandre Diop - a Franco-Senegalese artist who, according to the website, "uses discarded objects to create work that raises questions pertaining to sociopolitical, cultural and gender issues. Drawing inspiration from his European and African roots, he explores the legacies of colonialism and diaspora while tackling universal themes of ancestry, suffering, and historical violence". The open space with its large cathedral-esque windows floods the space with natural light, showcasing all the wonderful varied textures and highlighting all the materials that Diop uses in his work.

Once you exit this room, you will enter a three-level building that was once part of Randall Junior High School, a historically Black public school that ceased operations in 1978. The Rubells purchased this historic site from the Corcoran College of Art and Design in 2010 for $6.5 million. The building was the site for the inaugural What's Going On? when the museum opened in 2022.

Although quite disorienting to navigate at first, each level essentially follows a radial floor plan. There will be an exhibit in the middle of the level when you first come, and then out in all directions are hallways that will lead to individual rooms with their own exhibits relating to the overall current exhibition - Singular Views: 25 Artists.

One of the biggest flaws in the architecture of the building or more importantly, how the architecture is utilized, is the decision to install art in the narrow hallways. These hallways doubtfully will pass the modern fire and safety code. Large enough to fit one individual through, there would often be two-dimensional works hanging on both sides of the wall. The proximity between the visitors and the works would make any conservator nervous. There is a serious bottleneck where a visitor must wait for another to pass through before entering these spaces. Needless to say, when there is a person waiting, one cannot help but exit in a hurried manner. This takes away any chance for close looking or truly connecting and appreciating the work.

Overall, the exhibition was something you would come to expect of the Rubell Museum (so far that I have seen in DC): colorful, vibrant, electric and featuring young artists, some in their early or mid careers. The standouts this time for me were Amoako Boafo, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Rozeal, whom I will be covering in separate posts so they each have their own spotlights.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

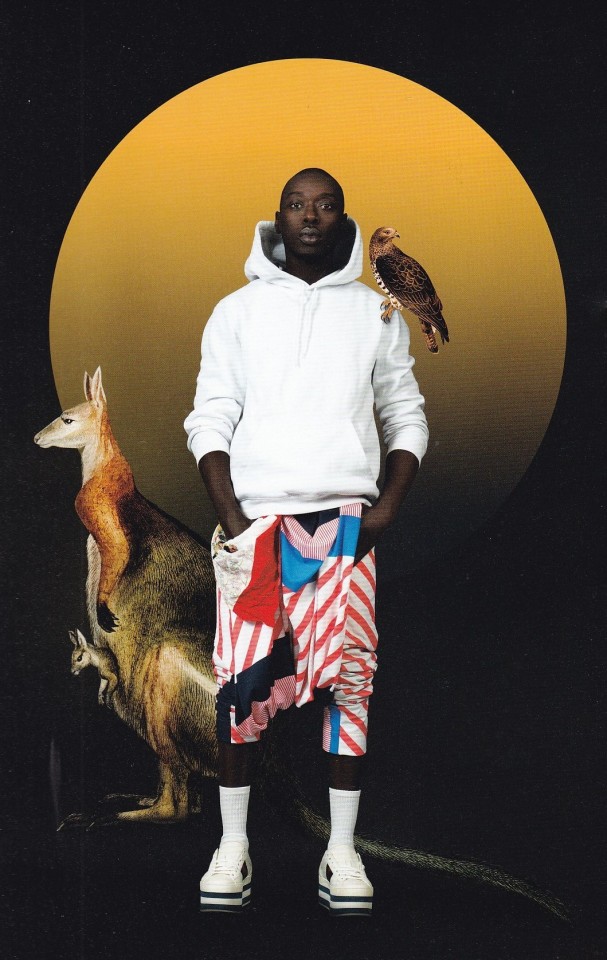

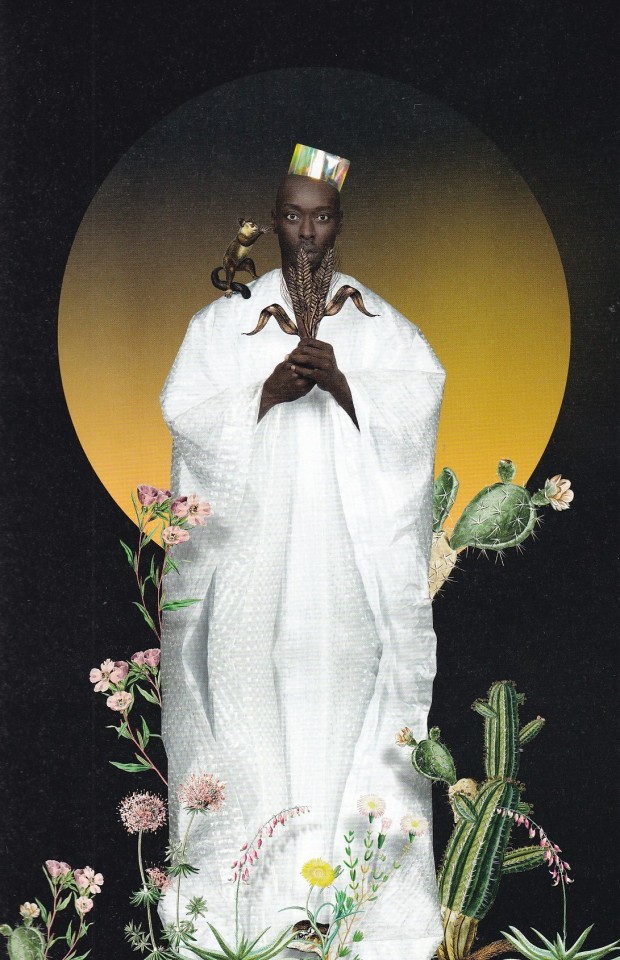

Omar Victor Diop

Renée Mussai, Imani Perry, Marvin Adoul

5 Continents Editions, Milano 2021, 96 pagine, cartonato, 45 illustrazioni a colori, 23,5 x 31 cm, Lingua francese-inglese , ISBN 978-88-7439-993-2

euro 45,00

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

Artista autodidatta, a 41 anni d’età Omar Victor Diop è uno dei fotografi più promettenti della sua generazione. La sua opera si inserisce nella tradizione africana della fotografia in studio, partendo dagli scatti di Seydou Keïta, Mama Casset e Malick Sidibé, un genere perfettamente padroneggiato e da cui si è progressivamente allontanato. L’opera Omar Victor Diop, in coedizione con la Galleria MAGNIN-A di Parigi, raccoglie per la prima volta le ultime tre serie emblematiche del fotografo: Diaspora (2014), Liberty (2017) e Allegoria (2021).

In Diaspora, Diop sceglie l’arte dell’autoritratto. Il fotografo senegalese incarna nelle sue immagini diciotto personalità della diaspora africana dai destini straordinari, ma dimenticati dalla storia del mondo occidentale. Vivacizzando le foto con oggetti legati al mondo del calcio, smorza la carica drammatica catapultando i suoi personaggi storici nel presente, inserendoli di fatto nel dibattito sull’immigrazione e l’integrazione degli stranieri nelle società europee.

Per Liberty, Diop continua la valorizzazione del continente africano e dell’esodo delle sue genti proponendo una lettura universale della storia della protesta del suo popolo. Giocando su riferimenti visivi e mescolando autoritratti e rappresentazioni, l’artista rivisita gli avvenimenti salienti di questa complessa vicenda, certamente diversi per epoca, luoghi e importanza, ma collegati dalla stessa ricerca di libertà troppo spesso ostacolata.

Con Allegoria inizia un nuovo capitolo del suo lavoro. Diop si appropria del tema fondamentale dell’ambiente e della sua importanza nel continente africano. Le sue opere raffigurano l’allegoria di un’umanità preoccupata per una natura che potrebbe diventare solo un ricordo nei manuali di scienze. L’Uomo, abbandonato alla sua dolorosa responsabilità, raccoglie attorno a sé questa Natura ridotta a mera rappresentazione.

26/12/22

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Omar Victor Diop#african photography#Galleria Magnin-a Paris#Diaspora#Liberty#Allegoria#photography books#fashion books#fashionbooksmilano

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ségou: La Terre en miettes by Maryse Condé

Ségou: La Terre en miettes picks up the story of Ségou: Les Murailles de terre several months after the Battle of Kassakéri (1856), in which Omar Tall inflicted a crushing defeat on the Bambaras. Mohammed, one of Dousika Traoré’s grandsons, loses one of his legs, whereas his cousin Olubunmi is captured and forced to serve in the army that wages Omar Tall’s jihad. Unbeknownst to both, their cousin Eucaristus is attending a seminary in England to become an Anglican priest.

The first two parts of the book are set during Omar Tall’s jihad. Omar Tall insists on a full conversion to Islam, citing a verse that says that muslims who have close alliances with infidels thereby become infidels themselves (see also Quran 3:28). His strict religious rules do not prevent him from having 800 wives. The moral high ground can be a slippery place.

Both in the part of West Africa that Omar Tall is trying to conquer and in the Sokoto Caliphate, people experience that Islam does not bring peace but provokes quarrels between peoples, families, neighbours and family members. Mohammed, who is a firm believer in Islam, has difficulty convincing his own family and the mansa that abandoning their resistance to Omar Tall is the best option. Nevertheless, he cites a hadith to Omar Tall that says that if two Muslims meet with swords in hand, both the aggressor and the victim will go to eternal hell. On the other hand, he cannot deny that he is a Bambara and his efforts to be both a good muslim and a good Bambara will eventually cost him his life.

After Omar Tall’s death, a new threat emerges from the increasing French influence in West Africa. This threat is different from Omar Tall’s, not only because it is not religiously inspired and because of the much greater military superiority, but because the French military leaders never appear as characters in the novel. This has the effect of turning the French into a force, though not a force of nature, but the force of greed. One of the muslims in the novel observes that starting a jihad against the French would not be an appropriate response because “the French have no soul”.

Questions of identity run through most of the novel, especially the last three parts. Samuel, the son of Eucaristus, meets Hollis Lynch, who thinks that former slaves in the African diaspora should be able to return to a country in Africa, which is “the source of original purity”. Ironically, he wants to give that new country a Greek name, Eleftheria (Greek for freedom) and he eventually dies trampled by a crowd of Fante people he was encouraging to assert their identity and to reject white interference in their culture. Samuel, whose mother is a Trelawny claiming descendance from the Jamaican Maroons, thinks he should look for his roots in Jamaica. When he eventually reaches the island, he learns that the Maroons now hunt runaway slaves for the British. They almost kill Samuel, whose illusions are thoroughly shattered.

In the mean time, Dieudonné, youngest son of Mohammed’s rejected wife Awa, grew up in Saint-Louis, where he often heard stories about Ségou from other Bambaras living in that city but not from his mother. He travels to Ségou, where he is almost killed on suspicion of being a spy for the French. Dieudonné’s brother Ahmed joined the Senegalese Tirailleurs. Because his mother never talked about his father or Ségou, he wants to exorcise this double absence by punishing Ségou. In the conflict between the French and the the peoples of present-day Mali, he comes face to face with his own half-brother Omar without realising it.

Women in this novel undergo decisions taken by men. Some of the wives of the Traoré men who return to Ségou are not descended from noble families and cannot stand that they are treated as a second-class wife next to a wife who is a princess. Some of these women leave their husbands, others complain about their fate, though rarely openly. Condé avoids turning her female characters into anachronistic proponents of Black feminism. (For example, female circumcision, as it is called in the novel, is mentioned only once, not by any of the Black characters, but by the French naval officer and explorer Eugène Mage.)

Like the first part of the novel, Ségou: La Terre en miettes doesn’t have a main character. This could simply be attributed to the literary genre of the family saga, but one of Chinua Achebe’s comments in connection with his own novel Arrow of God also seems to apply here: African literature has its roots in communal living and characters are to some degree “subject to non-human forces in the universe”.

This second part of Ségou confirms that Maryse Condé was a great storyteller. Publisher Robert Laffont should reset her book without the typographical errors the current edition contains.

Maryse Condé: Ségou: La Terre en miettes. Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 1985 (reprinted in 2020). ISBN 9780241293515 (428 pages). English translation: The Children of Segu. New York: Ballantine Books, 1990. (462 pages).

Review submitted by Tsundoku.

0 notes

Text

thoughts on exploring african culture as a diasporic african

peering in on the beauty and artistry of different african typologies as a Caribbean American is an experience i want to navigate honestly and unashamedly. what is my connection to this land? where do i originate within it, and would having that answer further isolate me from identifying with differing regions. today i was taken by senegalese culture, but theres a sense of shame in picking and choosing which cultures i find interesting. i was told i have ancestors from the congo. i am taken by these arab infused african typologies.

im happy for the women i see using their culture as precedent for their self expression and input for their creative output. where do i fit into this as a person from the diaspora. the thought of using these typologies one to one feels dishonest and embarrassing. i have no reference points or points of entry for engaging with the landscapes, textiles, language, etc.

i think adaptation through surrealism makes me feel safe. there is no point in ignoring my position as a diasporic African, if that is my lived experience than it is my strength. it only becomes a weakness when i turn away from it.

0 notes

Text

April 1-24, 1966, The First World Festival of Negro Arts, which is now known as FESMAN, launched its debut as the first modern cultural event celebrating global Black culture.

The Festival took place in Dakar, Senegal, and was initiated by Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor who saw it as a way to emphasize the importance of cultural development of newly independent African nations. The Festival’s theme centered around the significance of Black artistry and its role in promoting economic, political, and infrastructural development in Africa. Through literature, dance, and visual and auditory performances, Senghor hoped to facilitate the identification with African culture and creativity which challenged the prior limitations imposed during the age of colonization.

The event brought together more than 2,000 writers, artists, and musicians from throughout the African diaspora including 30 independent African nations, to celebrate the vast diversity within Black cultures. Renowned African American artists including Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, and Josephine Baker, performed in celebration of Africa’s cultural renaissance which mirrored their contributions to the Harlem Renaissance, the Jazz Age, and Negritude.

Following the events at the festival in Dakar in 1966, the Second World Festival of Negro Arts continued in Lagos, Nigeria some years later in 1977. This event was the largest pan-African event held in Africa. The most recent festival returned to its origin in Dakar nearly 30 years later in December 2010, to celebrate the significance of pan-Africanism and Black culture. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

ID: The image above is a screenshot of a quote tweet of @ firelorddany on twitter asking for unpopular opinions on Piandao. @ BeBraesFull replies: "He Blasian, which means that Black people exist in the world of avatar, and that's enough to upset some of y'all. *crying laughing emoji*" End ID.

So I've been thinking about this post a lot, wondering that if there was an African-based nation in ATLA (similar in concept to the Sun Warriors), what would their element be?

Quick note: I am partially African have absorbed lots of the culture and traditions from my family, but I am definitely no expert on anything. This is just me doing a little head scratcher.

Because my family is from the West coast of Africa, my first thought response was water. Many African tribes / peoples across the diaspora have a very strong connection to water and the ocean because of either proximity to or moving across the ocean. Where my family comes from, there is a very strong connection to fishing and rain because of how close they are to the equator (where there is a high rate of precipitation) and how close they are to the ocean, and the same applies for the nations that surround it. On top of that, thunder & lightning / storm gods are often high-ranking gods in many African West-coast pantheons (For example, Oya in the Yoruban religion or Nzazi in the Kongo religion). It could be argued that because of that, this theoretical group's element could be fire, I would suggest that this links back more to storms rather than lightning itself. There are also many gods of the rain, often depicted as important or high-ranking deities as well (Such as Oshun, goddess of love associated with rivers, and Yemaya, considered to be the Earth Mother and goddess of the oceans in Yoruban traditions or the Jola people's belief that in the beginning there were the gods of drought and rain respectively, Amongtong and Montogari or even Chicamassi-chinuinji, the ruler of the oceans and seas, and Mpulu Bunzi goddess of the rain and harvests in Kongo's pantheon). Rivers are thought to carry the spirits of the dead in many of the previous cultures as well. Water is also heavily linked to voodoo as a source of purity and is used in many religious practices. Even outside of just West Africa, Sothern Africa also has these connections to water through religious practices and is seen as a healing force, consistent with ATLA's characterization of water. And this is kind of irrelevant, but also the main name for African social/ethnic groups are "tribes", much like the water tribes in ATLA, so it would fit the current language used to describe waterbenders.

The other option that I think is most viable is earth. Earth is an widely used resource across Africa due to its appearances in housing, pottery/sculpture, argiculture, and in religious beliefs. Many traditional African building materials have a base made of clay that is usually mixed with some kind of dung to create firm and durable materials for housing. It helps keep the indoors cool throughout the seasons. This is seen across the continent and is a staple of African architecture. While there aren't as many central African deities based around the earth, there are some. Ala, goddess of the earth, fertility and morality, is the head goddess of the Igbo pantheon. Ogun, another important Yoruba deity, is the god of metal and metalworking. On top of that, there are some interesting fighting styles that could be used for earthbending like Senegalese wrestling, a martial art based on strength and sturdiness. I believe this provides enough of a basis to say that this is also a good option for this theoretical society.

When talking about fire, it is important to acknowledge that there are already the Sun Warriors. This sort of makes whatever I argue in this paragraph less relevant because there's not really a need for another firebending society. Regardless, there are some points to argue here. Both the Kongo and Egyptian pantheons had sun gods as their head god, Nzambi Mpungu and Ra respectively. Because firebending is based around the sun, it could be argued that this is a good basis for firebending. Fire is also a central element to the beliefs of the Fang people of Western Africa. Obviously, fire also appears in cooking and a few rituals, but that is not really exclusive to African societies. In my opinion, this is the weakest option because there isn't as much of that in-depth connection that can be found in the other options and because of the existence of the Sun Warriors.

Finally, there's air. Certain African traditions say that air carries the spirits of the dead. What's interesting about air deities across Africa is that they're not always central, but they are extremely common. In Egyptian mythology, the god Horus is a sky god. Again in Yoruba traditions, there is a minor air god by the name of Ayao. Ngewo, another sky god is the head god of the Mende people. The Igbo have minor air gods as well. While air doesn't have the strongest case, it seems to be relevant for a wide range of African religions/cultures.

Anyhoo, this is just my little note on this topic because it was living in my head rent free. Feel free to add on / correct anything that I've said.

Sources:

The Seven African Powers

Kongo Religion (sorry, it's just Wikipedia.)

Southern Africa's spiritual connections to water (Page 2)

Mud Housing

Igbo pantheon/religion (Wikipedia again)

Main Egyptian gods

Fang people

Senegalese Wrestling

Ngewo

Sad but true …..

I think it’s really cool that he’s based off of the (martial artist) fighting instructor and consultant of the series named Sifu Kisu who’s actually blasian in real life

If anyone doesn’t remember, he was Sokka’s teacher

847 notes

·

View notes

Text

As we witness ongoing protests by Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists, it’s worth exploring the roots of the movement in an earlier generation of Black intellectuals who sought to reclaim their cultural heritage and dignity in the face of colonial oppression. In a 2018 talk at the UCLA African Studies Center, Professor of Comparative Literature Frieda Ekotta drew a connection between the BLM movement and Négritude, arguing that both movements challenge(d) dominant systems of oppression for people of color, particularly Black people. As Ekotta explains:

Black Lives Matter reflects on history and demands that Black people be treated as human beings. This call for respect of the dignity of Black individuals, founded on historical analysis, echoes the negritude literary movement, which was hugely influential on Black culture, identity and empowerment.

Evolving out of the Black diaspora in the 1930s and led by Black Francophone writers such as French Caribbean poet Aimé Césaire, Senegalese poet and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor, and French Guianan poet Léon Damas, the Négritude movement condemned colonialism and racism while challenging narratives that historically relegated Black people to the margins and portrayed them as inferior or primitive.

Scholar of French and Black World Studies Babacar Camara points out that Négritude emerged as both a cultural and political movement in response to racism and oppression faced by Black people. He, too, argues that it remains relevant today as a means of cultural affirmation and survival, criticizing contemporary approaches to Négritude and Black Studies that fail to consider the specific historical and social conditions that gave rise to the movement. Camara’s view of Négritude supports Ekotta’s argument, positioning a knowledge of Négritude—and its ability to strengthen African and Black identity by promoting solidarity in the fight against oppression—as essential for understanding the injustices that Black communities have and continue to endure in society. Writes Camara:

Despite various assaults against Négritude, I show that it did not disappear altogether, and rather, it is still influencing any claim of Africanity (African identity and belonging). […] In terms of practical necessity, Négritude is a factor of unity in the long and fragmented struggle of Blacks against oppression.

Although marginalized in academic conversations and facing criticism, Négritude remains relevant to understanding Black and African identity. Camara suggests that African writers and artists resist the commodification, reification (objectification), and recuperation (the act of co-opting a subversive movement into a mainstream form) of Blackness by embracing African traditional values. By doing so, they are reviving Négritude as a means of cultural affirmation and survival.

Weekly Newsletter

Négritude and the Black Lives Matter movement share a common goal of challenging oppressive systems that affect Black communities by promoting solidarity and strengthening African and Black identity. As such, Négritude remains relevant in contemporary discussions surrounding systemic oppression. A recognition of Négritude also promotes a better understanding of artists and writers involved with the BLM movement and their efforts to challenge systemic racism and oppression of Black people in the United States and around the world.

0 notes

Photo

Un grazie a Abdou Mbar Sylla alla comunità Senegalese della diaspora ed al Dottor Mbacke Sarr per la profonda riflessione portata al convegno. Da Milano è iniziato un programma verso tutta la Lombardia #Senegal https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn9h6Q6Iy8S/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

idk people in the diaspora tend to have slightly different opinions than people born raised and living there like I'll be rooting for african countries as someone from the diaspora but idk if the Senegalese are like alright time to back Morocco. versus people think I'll support a Jamaican athlete when there isn't a Trinidadian one like... no?? who are they to me? but if you're a part of the Caribbean diaspora in the states of something I would understand why you'd do that

0 notes

Video

youtube

Little Senegal (Trailer)

“There has been much dialogue on tracing African American roots back to West Africa. But in this melancholic and reflective film, the subject, in this case, a tour guide at Gora Island’s slave fort museum in Goree, Senegal, sets out to find his relatives’ ancestors; who were taken as slaves to South Carolina at the beginning of the 19th century.The 2001 drama Little Senegal, directed by Algerian filmmaker Rachid Bouchareb, is now streaming on Netflix.

Kouyate plays Alloune, a man passionate about his African roots as part of the Jula people in Senegal. After some scrupulous research, Alloune travels to South Carolina, where he gets word from a Plantation family member about the whereabouts of his relative ancestor’s descendant, who has carried the Robinson surname. The search leads Alloune to the Little Senegal (Le Petit Senegal) section of Harlem, NY, where his first generation Senegalese nephew Hassan also lives along with his submissive wife in a small flat.

He tracks the address of his distant cousin, a convenience store owner named Ida Robinson, played by Sharon Hope. To her chagrin, Ida agrees to hire a more-than-eager Alloune to work as a store guard; unbeknownst to his real purpose for being there, Ida makes clear to Alloune her distrust towards Africans. But soon the embittered Ida befriends Alloune, as he sets out to help her search for her rebellious teen granddaughter (Malaaika Lacario), who is pregnant and missing.

The film sets out to explore the culture clash and apparent animosities between African Americans and Africans. Alloune’s nephew Hassan (Karim Koussein Traore) also expresses his disdain towards the Black Americans, especially given the experience shown in the film with a customer at the car shop he no longer works for. Hassan, perplexed by Alloune’s search and need for connection to his American distant cousin, tells him, “We’re too black for them! They don’t like us. Hold out your hand to them and they’ll stab it. Kill you even. They like you, but prefer your money.”

The film however, shows the gender distinctions and patriarchal institution of African marriages, in this case between Hassan and his wife. She’s fed up of being treated as a servant and starts learning English; in one scene, his uncle Alloune stops the controlling Hassan from physically abusing his wife.

Another subplot in the film is Hassan’s North African roommate, Karim (Roschdy Zem), who is in the process of entering a marriage for residency papers with Amaralis (Adetora Makinde), an African American female cab dispatcher. That marriage agreement soon turns complicated, as they both begin mixing business with pleasure. Those sequences serve to further explore dynamics between Americans and Africans.

The heart of the story, and what you’ll enjoy the most, is the connection of the gentle Alloune and the embittered and jaded Ida, whose character softens as their relationship deepens and blossoms romantically. The film’s climax, the revelation of Ida’s ancestry, is moving and cathartic. Kouyate gives another poignant, subdued and subtle performance. I had to look up actress Sharon Hope, who plays Ida. I’m surprised this film is her only acting credit; her dynamic performance against Kouyate is compelling and their chemistry resonates.

There’s a rather sad, or more a feeling of melancholia, ending to this film. There’s a stigma of shame when it comes to the legacy of slavery for Black Americans. This film explores a rich history of proud ancestors through the eyes of a Senegalese man. He represents a West Africa wanting to embrace those who seemingly lost all traces to their roots. There’s something to ponder and reflect upon when it comes to the displacement felt by many African Americans in this country, and this film shows that for many African Americans the generational gap may not be that wide after all, perhaps even a little over 200 years! Little Senegal manages to affectingly bridge a gap between Africans and African Americans, which in the end is perhaps much narrower than we have been presumed to believe.” via IndieWire

#little senegal#Rachid Bouchareb#Sotigui Kouyate#senegal#senegalese film#african american film#african americans and africans#african diaspora#senegalese diaspora#african american cinema#african film#african cinema#indie wire

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I was so excited after watching Beyoncé’s Homecoming. “If my country ass can do it, they can do it” - Beyoncé. This is me doing whatever ‘it’ is. There is a lot of talking, quite a few ums and ands. But hey, I did it ✨. If you haven’t seen Beyoncé’s HOMECOMING, it prolly ain’t for you 🍫.

#black women#african diaspora#black celebs#black people#HBCU#Beyoncé#homecoming#senegalesetwisted#senegalese twisted#sntwisted#twistedtalk#review

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage African Regal Queen Silver-Tone Clip-On Earrings

Simple, timeless, and elegant, pair of silver-tone earrings that wonderfully capture the essence of regal, African female beauty. Each earring is of the head of an African queen wearing a traditional headdress and earrings. The earrings have a light, undisturbed, natural patina and show some signs of wear and aging which are consistent with age. These very intriguing, clip-on earrings are lightweight and cling very gently on the ear with hinged clips.

#ayquebella#african#african queen#african royalty#african princess#african diaspora#african beauty#nubian queen#west african#nigerian princess#senegalese#liberian princess#african history#african heritage#african pride#wakanda#wakanda forever#etsy

9 notes

·

View notes