#scorpions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

did you know? the deathstalker scorpion is also known as the Palestine yellow scorpion, and is widespread throughout occupied Palestine!

want me to model a creature of your choice in 3D, or see how i make things like this? i'll be streaming requests in exchange for donations as part of Drawings for Gaza! we'll be live at the following times:

Monday, Feb 19th at 10PM EST

Friday, Feb 23rd at 2PM EST

Sunday, Feb 25th at 6PM EST

the genocide in Gaza is getting worse every day, and no resistance is too small. educate yourself; call your local representatives; buy eSIMs so people can stay connected; donate to Operation Olive Branch, UNRWA, or PCRF; don't look away, and don't stay silent!

#free palestine#palestine#scorpion#deathstalker#3d art#lures you in with cool bug facts. go help people#gif#bugs#scorpions

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

throwback to when I was working at my desk with Cu Rùa on my shoulder and suddenly heard a loud and abrupt fart… I genuinely was so startled at the volume of it and thought it was my dog but she was nowhere to be found. I turned my head and there he was, tail pointed down near my ear… next to a large pile of shit

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I've seen so many of our Centruroides hentzi scorpions over the years, but somehow never a mother carrying her tiny pinchy children until today. Invertebrate parenthood is so sweet. 🤎🤎

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

the transparent bugposting will continue until morale improves part 14/??

(all from photographs taken by me)

#inaturalist#naturalist#nature#ecology#zoology#biology#wildlife#pngposting#insect#insects#bug#bugblr#entomology#bugs#insectblr#photography#nature photography#wildlife photography#hawks photos#animal photography#spider#spiders#spiderblr#arachnid#arachnids#scorpion#scorpions#pseudoscorpions#beetles

842 notes

·

View notes

Text

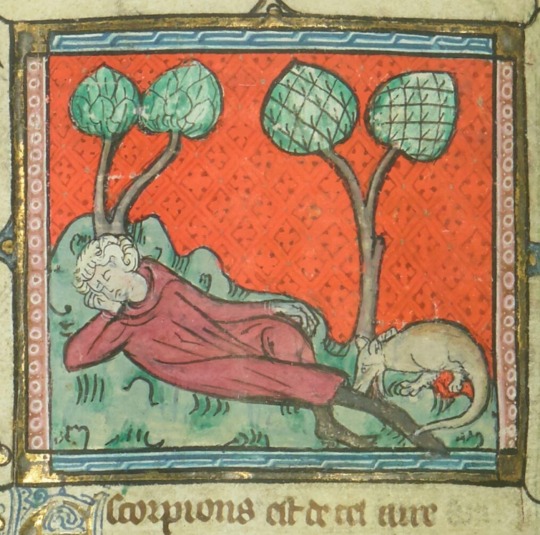

Medieval Scorpions Effortpost

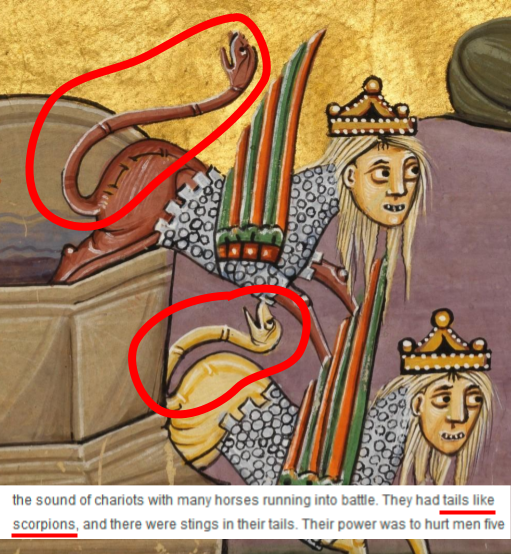

So yesterday I reblogged this post featuring an 11th-century depiction of the Apocalypse Locusts from Revelations, noting the following incongruity as another medieval scorpion issue:

The artist, as you can see, has interpreted "tails like scorpions" as meaning "glue cheerful-looking snakes to their butts".

Anyway, it occurred to me that the medieval scorpion thing might not be as widely known as I think it is, and that Tumblr would probably enjoy knowing about it if it isn't known already. So, finding myself unable to focus on the research I'm supposed to be doing, I decided to write about this instead. I'll just go ahead and put a cut here.

As we can see in the image above, at least one artist out there thought a "scorpion" was a type of snake. Which makes it difficult to draw "tails like scorpions", because a snake's tail is not that distinctive or menacing (maybe rattlesnakes, but they don't have those outside the Americas). So they interpreted "tails like scorpions" as "the tail looks like a whole snake complete with head".

Let me tell you. This is not a problem unique to this illustration.

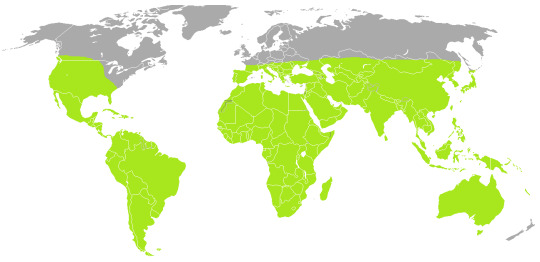

See, people throughout medieval Europe were aware of scorpions. As just alluded to, they are mentioned in the Bible, and if the people producing manuscripts in medieval Europe knew one thing, it was Stuff In Bible. They're also in the Zodiac, which medieval Europe had inherited through classical sources. However, let's take a look at this map:

That's Wikipedia's map of the native range of the Scorpiones order, i.e., all scorpion species. You may notice something -- the range just stops at a certain northern latitude. Pretty much all of northern Europe is scorpion-free. If you lived in the north half of Europe, odds were good you had never seen a scorpion in your life. But if you were literate or educated at all, or you knew they were a thing, because you'd almost certainly run across them being mentioned in texts from farther south. And those texts wouldn't bother to explain what a scorpion was, of course -- everyone knows scorpions, right? When was the last time you stopped to explain What Is Spiders?

So medieval writers and artists in northern Europe were kind of stuck. There was all this scorpion imagery and metaphor in the texts they liked to work from, but they didn't really know what a scorpion was. Writers could kind of work around it (there's a lot of "oh, it's a venomous creature, moving on"), but sometimes they felt the need to break it down better. For this, of course, they'd have to refer to a bestiary -- but due to Bestiary Telephone and the persistent need of bestiary authors to turn animals into allegories, one of the only visual details you got on scorpions was that they... had a beautiful face, which they used to distract people in order to sting them.

And look. I'm not here to yuck anyone's yum, but I would say that a scorpion's face has significant aesthetic appeal only for a fairly small segment of the population. I'm sure you could get an entomologist to rhapsodize about it a bit, but your average person on the street will not be entranced by the face of a scorpion. So this did not help the medieval Europeans in figuring out how to depict scorpions. There was also some semantic confusion -- see, in some languages (such as Old and Middle English), "worm" could be a general term for very small animals of any kind. But it also could mean "serpent".* So there were some, like our artist at the top of the post, who were pretty sure a scorpion was a snake. This was probably helped along by the fact that "venomous" was one of the only things everyone knew about them, and hey, snakes are venomous. Also, Pliny the Elder had floated the idea that there were scorpions in Africa that could fly, and at least one author (13th-century monk Bartholomaeus Anglicus) therefore suggested that they had feathers. I don't see that last one coming up much, I just share it because it's funny to me.

*English eventually resolved this by borrowing the Latin vermin for very small animals, using the specialized spelling wyrm for big impressive mythical-type serpents, and sticking with the more specific snake for normal serpents.

Some authors, like the anonymous author of the Ancrene Wisse, therefore suggested that a scorpion was a snake with a woman's face and a stinging tail. (Everyone seemed to be on the same page with regards to the fact that the sting was in the tail, which is in fact probably the most recognizable aspect of scorpions, so good job there.) However, while authors could avoid this problem, visual artists could not. And if you were illustrating a bestiary or a calendar, including a scorpion was not optional. So they had to take a shot at what this thing looked like.

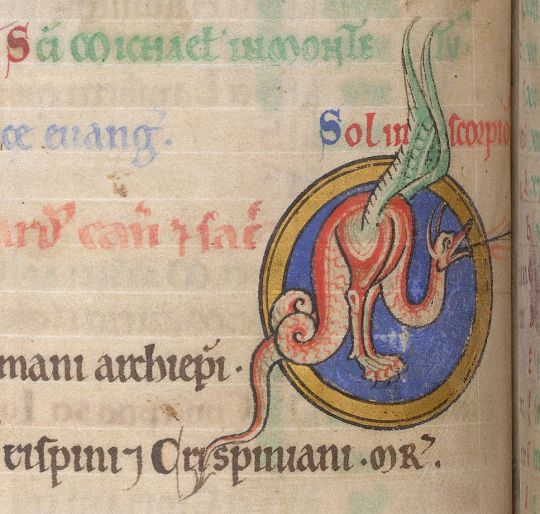

And so, after this way-too-long explanation, the thing you're probably here for: inaccurate medieval drawings of scorpions. (There are of course accurate medieval drawings of scorpions, from artists who lived in the southern part of Europe and/or visited places where scorpions lived; I'm just not showing you those.) And if you find yourself wondering, "how sure are you that that's meant to be a scorpion?" -- all of these are either from bestiaries or from calendars that include zodiac illustrations.

11th-century England, MS Arundel 60. (Be honest, without the rest of this post, if I had asked you to guess what animal this was supposed to be, would you have ever guessed “scorpion”?)

12th-century Germany, "Psalter of Henry the Lion". (Looks a bit undercooked. Kind of fetal.)

12th-century France, Peter Lombard's Sententiae. (Very colorful, itsy bitsy claws, what is happening with that tail?)

12th-century England, "The Shaftesbury Psalter". (So a scorpion is some sort of wyvern with a face like a duck, correct?)

13th-century France, Thomas de Cantimpré's Liber de natura rerum. (I’d give them credit for the silhouette not being that far off, but there’s a certain bestiary style where all the animals kind of look like that. Also note how few of these have claws.)

13th-century England, "The Bodley Bestiary". (Mischievous flying squirrel impales local man’s hand, local man fails to notice.)

13th-century England, Harley MS 3244. (A scorpion is definitely either a mouse or a fish. Either way it has six legs.)

13th-century England, Harley MS 3244. (Wait, no, it’s a baby theropod, and it has two legs. (Yes, this is the same manuscript, that’s not an error, this artist did four scorpions and no two are the same.))

13th-century England, Harley MS 3244. (Actually it’s a lizard with tiny ears and it has four legs.)

13th-century England, Harley MS 3244. (Now that we’re at the big fancy illustration, I think I’ve got it — it’s like that last one, but two legs, longer ears, and a less goofy face. Also I’ve decided it’s not pink anymore, I think that was the main problem.)

13th-century England, MS Kk.4.25. (A scorpion is a flat crocodile with a bear’s head.)

13th-century England, "The Huth Psalter". (Wyvern but baby! Does not seem to be enjoying biting its own tail.)

13th-century England, MS Royal 1 D X. (This triangular-headed gentlecreature gets the award for “closest guess at correct limb configuration”. If two of those were claws, I might actually believe this artist had seen a scorpion before, or at least a picture of one.)

13th-century England, "The Westminster Psalter". (A scorpion is the offspring of a wyvern and a fawn.)

13th-century England, "The Rutland Psalter". (Too many legs! Pull back! Pull back!)

13th or 14th-century France, Bestiaire d'amour rimé. (This is very similar to the fawn-wyvern, but putting it in an actual Scene makes it even more obvious that you’re just guessing.)

14th-century Netherlands, Jacob van Maerlant's Der Naturen Bloeme. (More top-down six-legged guys that look too furry to be arthropods.)

14th-century Germany, MS Additional 22413. (That is clearly a turtle.)

14th-century France, Matfres Eymengau de Beziers's Breviari d'amor. (Who came up with that head shape and what was their deal?)

15th-century England, "Bestiary of Ann Walsh". (Screw it, a scorpion is a big lizard that glares at you for trying to make me draw things I don’t know about.)

I've spent way too much time on this now. End of post, thank you to anyone who got all the way down here.

#medieval#medieval creatures#medieval art#scorpions#medieval scorpions#manuscript#medieval manuscripts#illuminated manuscript

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

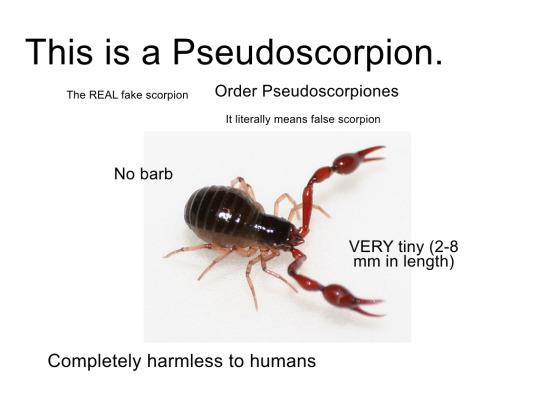

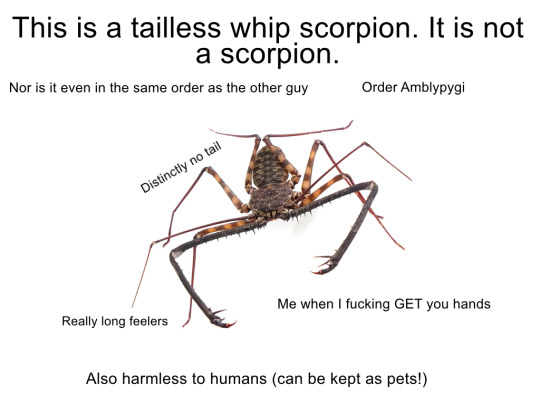

today i had a discussion with someone on the things we call scorpions that are not scorpions . because entomologists love to call things by names they are not actually.

ended up with this little . presentation. guide. thing. there are probably many, many more, but this is what we came up with on the Spot

#could've added that scorpionflies are not even true flies since they're not in Diptera#but if we want to start listing things we call flies that are not flies then we would need a whole separate massive list#clamtalk#ok i'm done talkign for today sorry. Very talkative. Much to say#bugs#bug tw#arachnids#arachnophobia#entomology#scorpions#ask to tag#bugposting

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Chelicerate anatomy, showing where the "head" is in each.

From Storer, Usinger, Stebbins, and Nybakken (1972) General Zoology (5th Ed.).

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm convinced pseudoscorpions were actually created by a mad scientist, they're the perfect fusion between a scorpion and a loaf of bread

(Pselaphochernes scorpioides. Male (R) and female (L) )

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

Probably my best artwork ever, two Asian forest scorpions locked in battle. The back is a mirror, which makes their jungle look larger. The plants aren't totally accurate to the biome due to the craft store being limited in their variety of native tropical-subtropical Asian plants

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boring. So boring.

《山河令》 WORD OF HONOR (2021) | Episode 35

How did these two devils end up together?

#screaming crying throwing up#my gif#wen kexing#zhou zishu#xie wang#scorpions#du xie#wenzhou#wenzhou gifset#word of honor episode 35#word of honor#wohedit#shan he ling#wenzhouedit#shledit#wordofhonoredit#asiandramaedit#cdramaedit#cdramasource#wuxiasource#lextag#cdramagifs#asianlgbtqdramas#asiandramasource#cdrama#wohdaily#dailyasiandramas#ENG from the Youku TL#(with minor editing to the glazed armor translation by me)

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

foxbloodshop on ig

#stim#clothes#fashion#glow in the dark#sfw#green#black#neon#glow#the second gif is saturated and brightened#so the glow is much more subtle in real life just fyi#dancing#people#jackets#shorts#bugs#insects#centipedes#fake animals#beetles#spiders#arthropods#arachnids#scorpions#ishy gifs#postish

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seems like a good use of a scorpion's discarded exoskeleton, they ain't using them no more.

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TwoForTuesday:

Félix Labisse (French, 1905–1982)

Les scorpions, 1959 gouache, 31 x 54 cm

Combat de scorpions, n.d. lithograph, 43 x 57.5 cm

#Félix Labisse#French art#surrealist art#surrealism#20th century art#scorpion#scorpions#pair#lithograph#painting#print#Two for Tuesday

651 notes

·

View notes

Text

(x)

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

A striped bark scorpion (Centruroides vittatus) flouresces under UV light in Texas, USA

by jciv

#god i love buthids#striped bark scorpion#scorpions#arachnids#centruroides vittatus#centruroides#buthidae#scorpiones#arachnida#arthropoda#wildlife: texas#wildlife: usa#wildlife: north america

145 notes

·

View notes