#saving em for top surgery recovery as a treat

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

bought annihilation by jeff vandermeer and severance by ling ma earlier..... 😈

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Dork - Colby Brock

Sam and Colby invite you and Jake to explore a recently abandoned hospital with them and things don’t go according to plan.

@traphousedaily’s favorite xplr video project with: @lonely-xplr, @sarcasmhadachild, @gothtara, @reddesertcolbs, @reinad-snc, @cartiercolby, @colbylover99, @xplrtrash, @goddess-of-time-and-magic, @xolbyz, @myguiltypleasures21

A/N: I didn’t have a lot of time to edit this one, so sorry for any errors there might be :)

Warnings: some curse words

Word Count: 1.8k+

--------------------------------------------------

“This is the Saint Luke’s Medical Hospital,” Sam announced as he zoomed in on the large building ahead of you four. You were slightly freaked out by the number of signs telling you that there was a guard dog around that you should beware of, but the boys did not seem to care that much.

“Look, there’s a big fat boob on the top,” Jake whispered to the camera as he pointed to the brown dome shape that sat at the top of the building that also had a small cone on top of that, resulting in a breast shape.

“There’s a big fat boob right here,” Colby giggled as he pointed to your chest. Your eyes widened and you stifled a laugh. You two made those kinds of jokes all the time, but he has never done it on camera.

“Colby!” you shouted before chuckling at the joke. The other two boys laughed as well before continuing to walk forward.

“You’re supposed to honk ‘em, right?” Jake asked as he made grabby hands, still going along with the boob joke. He then made a car honking noise with his mouth, causing you three to burst out in laughter.

“Yes, Jake. Go do that. Your goal today is to get to the top and honk that boobie,” Sam influence his friend before Jake ran ahead and he made grabby hands towards the building.

“How do we explain that to security if we get caught? Like what were you doing in here? We’re trying to honk boobies,” Colby joked as you rolled your eyes, realizing you were stuck to explore this hospital with three immature idiots. A noise caught you all off guard and you looked to Colby as he looked off at the building.

“That’s the dog,” Sam mumbled, looking in the same direction as Colby. You walked forward with the group to see the dog that sat behind the glass-paneled door. The dog barked with each step you guys got closer. You, Jake, and Sam backed away, but Colby’s dog-loving heart got closer to talk to it.

“We’re gonna come explore this hospital, okay? And we’re just going to look around for a second, alright? And then, we’re gonna leave, okay?” he told the pup in his talking to animals voice.

“Wait, dude, if there’s a dog right there, that means there’s a person right next to it,” Sam warned.

“There’s just a guy just listening to me say ‘We’re just going to explore this hospital’,” Colby laughed at the thought as he walked away from the dog. You all went around the building to find the door that y’all saw earlier when checking the perimeter of the place. There was a door that was wide open, so you all figured that would be the best way to enter. Once you guys arrived at the door, Colby peeked his head in and began making kissy noises.

“What are you doing?” Sam asked his best friend.

“I’m just making sure the dog knows that we’re coming in,” he spoke with a giggle. “Dude, wait. This is the part where we decide right now, do we wanna get bit by a dog or do we wanna be safe?”

“Did you bring the meat?” Sam asked Jake and Colby before the two pointed at each other.

“Colby’s got a fat ass. Bro, that dog has food for days. Ain’t that right, y/n?” Jake asked you as you nodded your head confidently.

“Why do I always have to go first?” Colby whined before grabbing the camera from Sam and walking forward. When he walked in the door, you all heard a click. You all walked away from the door to discuss the noise before deciding to go back.

“Dude, the click was because this door is automatic,” you told them when Sam went in and waved his hand near the door.

“Yeah, that’s it,” Sam said as he popped back out. “But it smells really bad. We should put on our masks in here.”

Colby handed you and Jake each a mask from Sam’s backpack before you put on the infamous black mask. Now, it was finally time to go in. Sam led the pack as he filmed, you and Colby followed with joined hands, and Jake was the caboose as he looked around at everything.

“You look adorable in your mask,” Colby bent down to whisper.

“You can only see my eyes, you asshole,” you giggled.

“Yeah, but I love your eyes.” You batted your eyelashes at the compliment before maintaining your focus ahead of you once more. Y’all made it to some stairs and made sure to take light and slow steps to lessen the risk of noise so the dog won’t find you. Once up the stairs, you went through a door that was already cracked open.

As you walked down the hallway with the guys, you realized how cool it was that you were doing. You had explored plenty of abandoned places with Colby, but they were all run down and broken and dirty. This place, however, still had running lights and literally felt like you were in a running hospital that had zero people in it.

You guys roamed the halls slowly as you tried to stay quiet. Eventually, you reached what looked like the hall where the patients lived. Everything was dead silent before Jake dropped something and it landed with a loud thud that bounced off the walls for anyone in the building to hear.

“Jake!” you whisper shouted.

“Sorry,” he mumbled, and you all moved to leave the room, not before he ran into something else and caused a ruckus. He muttered another apology and y’all left the room.

“Listen, we’re gonna fucking die. We’re gonna fucking die if y’all don’t stop making fucking noise. Okay?” Colby whispered to Sam who was filming him. You let out a small giggle before Jake spoke.

“It was my fault. I’m sorry.” Moments later, he made yet another noise while shutting a door behind him. Sam and Jake split off one way down the hall while you and Colby went the other.

“Yo, look at this,” Colby whispered when he knelt down to grab a sign that was laying on the floor. He turned around before showing it to you. It was a sign that told you which way the surgery recovery unit was and the stroke specialist unit too. “Should I keep this?”

“I don’t see why not.” He did a small happy dance and kissed you on the cheek before walking back to Sam and Jake.

Next, y’all found the best part of the building. It still had chairs and beds and literally looked like an actual hospital. You found the waiting area where the room was lined with red chairs. The next room over had some beds in it, but that was it. The last room in the hall looked the best. It had beds, counters, cabinets, an overhead light that you could move around, but you guys couldn’t stay long because a whistle was heard. So quickly, you four took a thumbnail picture before trying to leave. Of course, the boys got sidetracked when they saw a microphone that was linked to a speaker system.

“Sir, your penis appointment is scheduled,” Jake whispered into the mic before Colby went next.

“Could we have Larry with the case of gonorrhea come to the front office please. Thank you.”

Then, they realized it was time to go. Y’all speed-walked the way you came, but when you guys reached a door, Colby accidentally pushed the handle and an alarm sounded went off.

“Oh, shit. Shit. Shit. Shit,” Sam mumbled as speed walking turned into running. You four ran down the stairs and out of the building. Y’all walked slowly for a second to catch your breath and then took off again for the car. You threw open the back door and slipped in, leaving the door open so Jake could get in too. Colby placed the surgery sign next to you and got in the front. Right as Colby drove off, a police car passed by and turned into the hospital.

“That was crazy,” you stated as your breathing finally calmed down.

“I kinda wanna explore more of it next time,” Jake told Sam. You looked at him with wide eyes. The one who caused most of the noise wanted to go back. He may not have tripped the alarm this time, but if there was going to be a next time, he definitely would be the one to do it. “I feel like we should do a part two.”

“I feel like we should do a part two to that,” Sam agreed as he looked to Colby. Jake and Sam kept encouraging the idea before Colby spoke up.

“Yo, I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

“You don’t think that’s a good idea?” Sam questioned.

“No, we just barely got out of there.” Colby continued.

“And Jake can’t stay quiet to save his life,” you added before Jake gasped.

“Hey!”

“It’s true,” you told him with a smile.

“What if we bring dog treats?” Sam suggested.

“For the police? Because the dog wasn’t coming for us. It was the police,” you said to them.

“Okay, let’s think reasonably here,” Colby told Jake and Sam.

“What if we did? Like what if we got dog treats?” Jake imagined.

“No,” Colby protested.

“Do you think they’re trained not to care about anything?” Sam asked.

“Yes!” Colby said with enthusiasm. You rolled your eyes in the backseat. Sam was supposed to be the smart one, but right now, he wasn’t really showing that. “Okay, you really think a dog is gonna see you and start charging at you and you’re like ‘Hey, here’s a treat. Go get it,’ and it’s just gonna go. Like, come on now.”

“That stuff only happens in cartoons, Sam,” you told the blond.

“Alright, eighty-five thousand likes and we’ll do it,” he said to the camera as he completely ignored what you and Colby had said which you two gave up and nodded along.

Later on when you all came back to the trap house, you and Colby laid in bed to think about what had happened.

“That was crazy,” you started as your head hit his chest.

“I can’t believe they thought we just needed some dog treats, and it would all be better.”

“I can believe that Jake would think that, but I thought Sam was smarter than that.” You both laughed before silence fell over you two.

“But that place was really cool and pretty. Thanks for taking me,” you whispered.

“You’re really cool and pretty,” Colby added in.

“You are such a dork,” you giggled before kissing his lips.

“I’m your dork though.”

“Yes, you are my dork.”

#colby#cole robert brock#colby brock#Sam and Colby#colby imagine#colby x reader#colby fanfic#colby fanfiction#colby brock imagine#colby brock x reader#fanfic#fanfiction#colby brock fanfic#colby brock fanfiction#y/n#xplr#traphouse#sam#sam golbach#jake#jake webber#traphousedaily

478 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/how-to-keep-your-knees-safe-and-injury-free-during-a-yoga-class/

How to Keep Your Knees Safe and Injury-Free During a Yoga Class

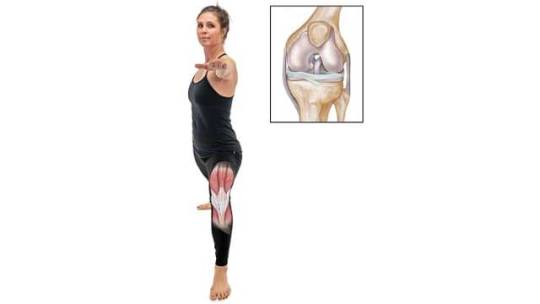

Anatomy of the knee

PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER DOUGHERTY; ILLUSTRATIONS: MICHELE GRAHAM

In 2007, I slipped while descending a steep trail in Shenandoah National Park. I took a hard blow to the outside of my left knee, shredding the lateral meniscus and articular cartilage and dislocating the kneecap. I faced major surgeries to save the knee from a partial joint replacement. My orthopedic surgeon was upfront: Recovery would be long and arduous. More than anything else, my mindset would be the key to my healing. That meant I needed to cultivate a nurturing relationship with my knees.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Fortunately, prior to the accident I’d been a yoga practitioner with a daily meditation habit for 19 years. Before surgery, I dedicated an hour a day to channeling love and gratitude into my knees. By the time I was wheeled into the operating room for the first of two surgeries that ultimately restored the joint’s structure, the knee had become my most beloved body part. I had learned to celebrate its complexity and vulnerability, and to fine-tune movements to treat it well. The knee is the body’s nexus of faith and duty: One of the first things we do when we seek strength or mercy is get down on our knees. We also drop to our knees when we pledge ourselves to a path of devotion. Each knee is the grand arbiter of mechanical forces received from the foot and hip. For better or worse, the knee adjusts itself to balance and transmit the energies of impact, shear (sliding forces), and torsion (twisting forces).

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

See also Essential Foot and Leg Anatomy Every Yogi Needs to Know

The knee is often described as a hinge joint, but that’s not the whole story. To the eye, it resembles a hinge because its primary movements are flexion (bending, to draw the thigh and calf toward each other) and extension (straightening, to move the thigh and calf away from each other). In reality, the knee is a modified hinge joint. It glides, and rotates. This makes it more versatile but also more vulnerable. Its range of motion becomes clear when you compare it with the elbow. Bend and straighten your elbow several times. The movement feels similar to opening and closing a laptop. Try it again by moving between Plank Pose and Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose). Now try Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose II), placing your front hand on the inner part of your front knee. Bend your front knee (flexion) and feel the thigh bone, or femur, glide forward and rotate—moving the knee up and out. Straighten your knee (extension) and feel the femur glide backward and rotate—moving the knee down and in.

To keep stable, the knee relies on tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the joint capsule itself, not large muscles. Among standing yoga poses, Tadasana (Mountain Pose) is most stable for the knee because there is maximal contact between the end of the femur and tibial plateau (the top of the tibia, or shin bone). Things go awry, though, if you “lock” your knees. When we hyperextend—and many of us do so without conscious thought—we excessively squeeze the anterior, or frontal, aspect of the menisci (see drawing), pushing the tissues backward, out of their natural placement. Instead, practice standing with your knees in a “relaxed straight”: stand and press back through one of your knees. Then firm your calf muscles toward your shin bone. Notice how all your leg muscles engage. Take your attention to the middle of your knee. It should feel very stable. Practicing this action over time will reeducate your muscles and correct hyperextension. Also, the inner parts of the knee are larger, thicker, and deeper than the outer parts. This anatomical asymmetry makes it normal for the kneecaps to slightly glance toward each other in poses such as Tadasana and Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose). Perhaps you’ve heard the cue to point your kneecaps directly forward in straight-leg asana? Don’t do it; it can injure the knee because it overrides the structure and function of the joint.

See also Anatomy 101: Are Muscular Engagement Cues Doing More Harm Than Good?

The knee is least stable when bent. When we flex our knees, as in Virabhadrasana II, we have less contact between the femur and tibia. When there is less bony contact, connective tissues strain and become more vulnerable. The vastus medialis, the inner muscle of the front thigh, is primarily responsible for keeping the patella, or kneecap, in its femoral sulcus, the groove at the end of the thigh bone. Ideally, we want the kneecap to slide smoothly up and down that groove, so that the patella functions efficiently as a fulcrum when we bend and straighten the knee. But the vastus medialis is much smaller than the vastus lateralis, on the outside of the front thigh. This strength imbalance in the front thigh muscles, or quadriceps, can cause the kneecap to pull out and up, creating pain in everything from walking to bent-leg standing asana. Lunge poses often make it worse. But we can develop balance between the muscles through “quad setting.” Sit in Dandasana (Staff Pose) with a rolled towel under your knees, toes pointed up. Press out through your heels. Then, press down through your knees, leading with the inner knee. Hold for 10-20 seconds, release, and repeat to fatigue.

Remember, the knees, stuck in the middle, absorb energy from the feet and hips. If you take them beyond normal rotation or put too much pressure on them when bent, you increase the risk of harming your ACL. In turn, several poses demand a high degree of caution. Some I’ve stopped practicing altogether.

Bhekasana (Frog Pose): Places strain on the ACL and medial meniscus because of torsion from trying to draw the soles down and toward the outer hips.

Virasana (Hero Pose): When practiced with the knees together and feet outside the hips, we push maximal range of motion for most people and add rotational strain multiplied by body weight.

Padmasana (Lotus Pose): Without sufficient mobility in the hips (and some of us will never have it due to our particular anatomy), our knees twist too much. The primary axis of movement in the body is the hips, a true ball-and-socket joint uniquely suited to rotation.

Pasasana (Noose Pose): Without sufficient strength in the hamstrings and calves, gravity wins, putting undue pressure on the knees, which strains the ACL. Laxity in the ACL can reduce power and stability in the knee.

Now that I’ve laid out what to avoid, here is what I recommend. Try this homework for two weeks to get to know your knees.

See also Fascial Glide Exercise for Functional Quads and Healthy Knees

Take a Good Look at Your Knees

If healthful for you, take Adho Mukha Svanasana, and look at your knees. Notice that the inner knees naturally move back farther than the outer knees and the kneecaps glance toward each other. Remember: This is normal!

Gain Knowledge about the Knee Muscles

Sit in Dandasana. With relaxed thighs, lightly grasp the inner and outer edges of your patellae and wiggle them side to side. Lightly grasp the upper and lower edges of your patellae and gently slide them up and down. Next, engage your thighs. Notice how the patellae cinch into the ends of the femurs. The moral of this story? Use your muscles, instead of mobility, to move your knees in asana.

Show Those Knees from Gratitude!

Rest your hands on your knees and send them love. They do so much for you amid so many demands. Show ’em gratitude! When a body part hurts or doesn’t do what we think it should, we often believe it has failed us. More likely, we have failed our body part by blaming or ignoring it. Gratitude is the antidote to shifting that relationship.

See also Practice These Yoga Exercises to Keep Your Knees Healthy

Yoga Knee Anatomy 101

Avoid injury by understanding how connective tissues help knees move, bear weight, and respond to strain.

Meniscus: Pads the space between the femur and tibia. This C-shaped structure also deepens the tibial plateau and helps stabilize the knee, especially the medial meniscus, which firmly attaches to the joint capsule and resists shear and rotation. Each knee has two menisci.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Functions like a stiff bungee cord to keep tibia from sliding too far ahead of femur. It’s one of the most commonly injured parts of the knee due to twisting actions that overstretch or tear it. That means many yoga poses put it at risk.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Keeps the knee from buckling inward. Also works with the ACL to stop the tibia from sliding too far forward. The MCL typically gets injured in sports with heavy physical contact and sudden changes in direction, such as football. It is not commonly injured in asana, though avoid “knee drift” toward the midline of the body in bent-leg asana; when the knee is in flexion, center the kneecap toward the space between the second and third toes.

See also Anatomy 101: Why Anatomy Training is Essential for Yoga Teachers

About our expert

Mary Richards, MS, C-IAYT, ERYT, YACEP, has been practicing yoga for almost 30 years and travels around the country teaching anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. A hard-core movement nerd and former NCAA athlete, Mary has a master’s degree in yoga therapy.

Learn more Study Experiential Anatomy online with Mary and Judith Hanson Lasater. Sign up today at judithhansonlasater.com/yj.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function() n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments) ;if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function() fbq('init', '1397247997268188'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); var contentId = 'ci02479c2cb0002481'; if (contentId !== '') fbq('track', 'ViewContent', content_ids: [contentId], content_type: 'product'); )();

Source link

0 notes

Link

Exploring how your knees move can lead to a balanced relationship between stability and vulnerability, on and off the mat.

Anatomy of the knee

In 2007, I slipped while descending a steep trail in Shenandoah National Park. I took a hard blow to the outside of my left knee, shredding the lateral meniscus and articular cartilage and dislocating the kneecap. I faced major surgeries to save the knee from a partial joint replacement. My orthopedic surgeon was upfront: Recovery would be long and arduous. More than anything else, my mindset would be the key to my healing. That meant I needed to cultivate a nurturing relationship with my knees.

Fortunately, prior to the accident I’d been a yoga practitioner with a daily meditation habit for 19 years. Before surgery, I dedicated an hour a day to channeling love and gratitude into my knees. By the time I was wheeled into the operating room for the first of two surgeries that ultimately restored the joint’s structure, the knee had become my most beloved body part. I had learned to celebrate its complexity and vulnerability, and to fine-tune movements to treat it well. The knee is the body’s nexus of faith and duty: One of the first things we do when we seek strength or mercy is get down on our knees. We also drop to our knees when we pledge ourselves to a path of devotion. Each knee is the grand arbiter of mechanical forces received from the foot and hip. For better or worse, the knee adjusts itself to balance and transmit the energies of impact, shear (sliding forces), and torsion (twisting forces).

See also Essential Foot and Leg Anatomy Every Yogi Needs to Know

The knee is often described as a hinge joint, but that’s not the whole story. To the eye, it resembles a hinge because its primary movements are flexion (bending, to draw the thigh and calf toward each other) and extension (straightening, to move the thigh and calf away from each other). In reality, the knee is a modified hinge joint. It glides, and rotates. This makes it more versatile but also more vulnerable. Its range of motion becomes clear when you compare it with the elbow. Bend and straighten your elbow several times. The movement feels similar to opening and closing a laptop. Try it again by moving between Plank Pose and Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose). Now try Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose II), placing your front hand on the inner part of your front knee. Bend your front knee (flexion) and feel the thigh bone, or femur, glide forward and rotate—moving the knee up and out. Straighten your knee (extension) and feel the femur glide backward and rotate—moving the knee down and in.

To keep stable, the knee relies on tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the joint capsule itself, not large muscles. Among standing yoga poses, Tadasana (Mountain Pose) is most stable for the knee because there is maximal contact between the end of the femur and tibial plateau (the top of the tibia, or shin bone). Things go awry, though, if you “lock” your knees. When we hyperextend—and many of us do so without conscious thought—we excessively squeeze the anterior, or frontal, aspect of the menisci (see drawing), pushing the tissues backward, out of their natural placement. Instead, practice standing with your knees in a “relaxed straight”: stand and press back through one of your knees. Then firm your calf muscles toward your shin bone. Notice how all your leg muscles engage. Take your attention to the middle of your knee. It should feel very stable. Practicing this action over time will reeducate your muscles and correct hyperextension. Also, the inner parts of the knee are larger, thicker, and deeper than the outer parts. This anatomical asymmetry makes it normal for the kneecaps to slightly glance toward each other in poses such as Tadasana and Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose). Perhaps you’ve heard the cue to point your kneecaps directly forward in straight-leg asana? Don’t do it; it can injure the knee because it overrides the structure and function of the joint.

See also Anatomy 101: Are Muscular Engagement Cues Doing More Harm Than Good?

The knee is least stable when bent. When we flex our knees, as in Virabhadrasana II, we have less contact between the femur and tibia. When there is less bony contact, connective tissues strain and become more vulnerable. The vastus medialis, the inner muscle of the front thigh, is primarily responsible for keeping the patella, or kneecap, in its femoral sulcus, the groove at the end of the thigh bone. Ideally, we want the kneecap to slide smoothly up and down that groove, so that the patella functions efficiently as a fulcrum when we bend and straighten the knee. But the vastus medialis is much smaller than the vastus lateralis, on the outside of the front thigh. This strength imbalance in the front thigh muscles, or quadriceps, can cause the kneecap to pull out and up, creating pain in everything from walking to bent-leg standing asana. Lunge poses often make it worse. But we can develop balance between the muscles through “quad setting.” Sit in Dandasana (Staff Pose) with a rolled towel under your knees, toes pointed up. Press out through your heels. Then, press down through your knees, leading with the inner knee. Hold for 10-20 seconds, release, and repeat to fatigue.

Remember, the knees, stuck in the middle, absorb energy from the feet and hips. If you take them beyond normal rotation or put too much pressure on them when bent, you increase the risk of harming your ACL. In turn, several poses demand a high degree of caution. Some I’ve stopped practicing altogether.

Bhekasana (Frog Pose): Places strain on the ACL and medial meniscus because of torsion from trying to draw the soles down and toward the outer hips.

Virasana (Hero Pose): When practiced with the knees together and feet outside the hips, we push maximal range of motion for most people and add rotational strain multiplied by body weight.

Padmasana (Lotus Pose): Without sufficient mobility in the hips (and some of us will never have it due to our particular anatomy), our knees twist too much. The primary axis of movement in the body is the hips, a true ball-and-socket joint uniquely suited to rotation.

Pasasana (Noose Pose): Without sufficient strength in the hamstrings and calves, gravity wins, putting undue pressure on the knees, which strains the ACL. Laxity in the ACL can reduce power and stability in the knee.

Now that I’ve laid out what to avoid, here is what I recommend. Try this homework for two weeks to get to know your knees.

See also Fascial Glide Exercise for Functional Quads and Healthy Knees

Take a Good Look at Your Knees

If healthful for you, take Adho Mukha Svanasana, and look at your knees. Notice that the inner knees naturally move back farther than the outer knees and the kneecaps glance toward each other. Remember: This is normal!

Gain Knowledge about the Knee Muscles

Sit in Dandasana. With relaxed thighs, lightly grasp the inner and outer edges of your patellae and wiggle them side to side. Lightly grasp the upper and lower edges of your patellae and gently slide them up and down. Next, engage your thighs. Notice how the patellae cinch into the ends of the femurs. The moral of this story? Use your muscles, instead of mobility, to move your knees in asana.

Show Those Knees from Gratitude!

Rest your hands on your knees and send them love. They do so much for you amid so many demands. Show ’em gratitude! When a body part hurts or doesn’t do what we think it should, we often believe it has failed us. More likely, we have failed our body part by blaming or ignoring it. Gratitude is the antidote to shifting that relationship.

See also Practice These Yoga Exercises to Keep Your Knees Healthy

Yoga Knee Anatomy 101

Avoid injury by understanding how connective tissues help knees move, bear weight, and respond to strain.

Meniscus: Pads the space between the femur and tibia. This C-shaped structure also deepens the tibial plateau and helps stabilize the knee, especially the medial meniscus, which firmly attaches to the joint capsule and resists shear and rotation. Each knee has two menisci.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Functions like a stiff bungee cord to keep tibia from sliding too far ahead of femur. It’s one of the most commonly injured parts of the knee due to twisting actions that overstretch or tear it. That means many yoga poses put it at risk.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Keeps the knee from buckling inward. Also works with the ACL to stop the tibia from sliding too far forward. The MCL typically gets injured in sports with heavy physical contact and sudden changes in direction, such as football. It is not commonly injured in asana, though avoid “knee drift” toward the midline of the body in bent-leg asana; when the knee is in flexion, center the kneecap toward the space between the second and third toes.

See also Anatomy 101: Why Anatomy Training is Essential for Yoga Teachers

About our expert

Mary Richards, MS, C-IAYT, ERYT, YACEP, has been practicing yoga for almost 30 years and travels around the country teaching anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. A hard-core movement nerd and former NCAA athlete, Mary has a master’s degree in yoga therapy.

Learn more Study Experiential Anatomy online with Mary and Judith Hanson Lasater. Sign up today at judithhansonlasater.com/yj.

0 notes

Link

Exploring how your knees move can lead to a balanced relationship between stability and vulnerability, on and off the mat.

Anatomy of the knee

In 2007, I slipped while descending a steep trail in Shenandoah National Park. I took a hard blow to the outside of my left knee, shredding the lateral meniscus and articular cartilage and dislocating the kneecap. I faced major surgeries to save the knee from a partial joint replacement. My orthopedic surgeon was upfront: Recovery would be long and arduous. More than anything else, my mindset would be the key to my healing. That meant I needed to cultivate a nurturing relationship with my knees.

Fortunately, prior to the accident I’d been a yoga practitioner with a daily meditation habit for 19 years. Before surgery, I dedicated an hour a day to channeling love and gratitude into my knees. By the time I was wheeled into the operating room for the first of two surgeries that ultimately restored the joint’s structure, the knee had become my most beloved body part. I had learned to celebrate its complexity and vulnerability, and to fine-tune movements to treat it well. The knee is the body’s nexus of faith and duty: One of the first things we do when we seek strength or mercy is get down on our knees. We also drop to our knees when we pledge ourselves to a path of devotion. Each knee is the grand arbiter of mechanical forces received from the foot and hip. For better or worse, the knee adjusts itself to balance and transmit the energies of impact, shear (sliding forces), and torsion (twisting forces).

See also Essential Foot and Leg Anatomy Every Yogi Needs to Know

The knee is often described as a hinge joint, but that’s not the whole story. To the eye, it resembles a hinge because its primary movements are flexion (bending, to draw the thigh and calf toward each other) and extension (straightening, to move the thigh and calf away from each other). In reality, the knee is a modified hinge joint. It glides, and rotates. This makes it more versatile but also more vulnerable. Its range of motion becomes clear when you compare it with the elbow. Bend and straighten your elbow several times. The movement feels similar to opening and closing a laptop. Try it again by moving between Plank Pose and Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose). Now try Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose II), placing your front hand on the inner part of your front knee. Bend your front knee (flexion) and feel the thigh bone, or femur, glide forward and rotate—moving the knee up and out. Straighten your knee (extension) and feel the femur glide backward and rotate—moving the knee down and in.

To keep stable, the knee relies on tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the joint capsule itself, not large muscles. Among standing yoga poses, Tadasana (Mountain Pose) is most stable for the knee because there is maximal contact between the end of the femur and tibial plateau (the top of the tibia, or shin bone). Things go awry, though, if you “lock” your knees. When we hyperextend—and many of us do so without conscious thought—we excessively squeeze the anterior, or frontal, aspect of the menisci (see drawing), pushing the tissues backward, out of their natural placement. Instead, practice standing with your knees in a “relaxed straight”: stand and press back through one of your knees. Then firm your calf muscles toward your shin bone. Notice how all your leg muscles engage. Take your attention to the middle of your knee. It should feel very stable. Practicing this action over time will reeducate your muscles and correct hyperextension. Also, the inner parts of the knee are larger, thicker, and deeper than the outer parts. This anatomical asymmetry makes it normal for the kneecaps to slightly glance toward each other in poses such as Tadasana and Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose). Perhaps you’ve heard the cue to point your kneecaps directly forward in straight-leg asana? Don’t do it; it can injure the knee because it overrides the structure and function of the joint.

See also Anatomy 101: Are Muscular Engagement Cues Doing More Harm Than Good?

The knee is least stable when bent. When we flex our knees, as in Virabhadrasana II, we have less contact between the femur and tibia. When there is less bony contact, connective tissues strain and become more vulnerable. The vastus medialis, the inner muscle of the front thigh, is primarily responsible for keeping the patella, or kneecap, in its femoral sulcus, the groove at the end of the thigh bone. Ideally, we want the kneecap to slide smoothly up and down that groove, so that the patella functions efficiently as a fulcrum when we bend and straighten the knee. But the vastus medialis is much smaller than the vastus lateralis, on the outside of the front thigh. This strength imbalance in the front thigh muscles, or quadriceps, can cause the kneecap to pull out and up, creating pain in everything from walking to bent-leg standing asana. Lunge poses often make it worse. But we can develop balance between the muscles through “quad setting.” Sit in Dandasana (Staff Pose) with a rolled towel under your knees, toes pointed up. Press out through your heels. Then, press down through your knees, leading with the inner knee. Hold for 10-20 seconds, release, and repeat to fatigue.

Remember, the knees, stuck in the middle, absorb energy from the feet and hips. If you take them beyond normal rotation or put too much pressure on them when bent, you increase the risk of harming your ACL. In turn, several poses demand a high degree of caution. Some I’ve stopped practicing altogether.

Bhekasana (Frog Pose): Places strain on the ACL and medial meniscus because of torsion from trying to draw the soles down and toward the outer hips.

Virasana (Hero Pose): When practiced with the knees together and feet outside the hips, we push maximal range of motion for most people and add rotational strain multiplied by body weight.

Padmasana (Lotus Pose): Without sufficient mobility in the hips (and some of us will never have it due to our particular anatomy), our knees twist too much. The primary axis of movement in the body is the hips, a true ball-and-socket joint uniquely suited to rotation.

Pasasana (Noose Pose): Without sufficient strength in the hamstrings and calves, gravity wins, putting undue pressure on the knees, which strains the ACL. Laxity in the ACL can reduce power and stability in the knee.

Now that I’ve laid out what to avoid, here is what I recommend. Try this homework for two weeks to get to know your knees.

See also Fascial Glide Exercise for Functional Quads and Healthy Knees

Take a Good Look at Your Knees

If healthful for you, take Adho Mukha Svanasana, and look at your knees. Notice that the inner knees naturally move back farther than the outer knees and the kneecaps glance toward each other. Remember: This is normal!

Gain Knowledge about the Knee Muscles

Sit in Dandasana. With relaxed thighs, lightly grasp the inner and outer edges of your patellae and wiggle them side to side. Lightly grasp the upper and lower edges of your patellae and gently slide them up and down. Next, engage your thighs. Notice how the patellae cinch into the ends of the femurs. The moral of this story? Use your muscles, instead of mobility, to move your knees in asana.

Show Those Knees from Gratitude!

Rest your hands on your knees and send them love. They do so much for you amid so many demands. Show ’em gratitude! When a body part hurts or doesn’t do what we think it should, we often believe it has failed us. More likely, we have failed our body part by blaming or ignoring it. Gratitude is the antidote to shifting that relationship.

See also Practice These Yoga Exercises to Keep Your Knees Healthy

Yoga Knee Anatomy 101

Avoid injury by understanding how connective tissues help knees move, bear weight, and respond to strain.

Meniscus: Pads the space between the femur and tibia. This C-shaped structure also deepens the tibial plateau and helps stabilize the knee, especially the medial meniscus, which firmly attaches to the joint capsule and resists shear and rotation. Each knee has two menisci.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Functions like a stiff bungee cord to keep tibia from sliding too far ahead of femur. It’s one of the most commonly injured parts of the knee due to twisting actions that overstretch or tear it. That means many yoga poses put it at risk.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Keeps the knee from buckling inward. Also works with the ACL to stop the tibia from sliding too far forward. The MCL typically gets injured in sports with heavy physical contact and sudden changes in direction, such as football. It is not commonly injured in asana, though avoid “knee drift” toward the midline of the body in bent-leg asana; when the knee is in flexion, center the kneecap toward the space between the second and third toes.

See also Anatomy 101: Why Anatomy Training is Essential for Yoga Teachers

About our expert

Mary Richards, MS, C-IAYT, ERYT, YACEP, has been practicing yoga for almost 30 years and travels around the country teaching anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. A hard-core movement nerd and former NCAA athlete, Mary has a master’s degree in yoga therapy.

Learn more Study Experiential Anatomy online with Mary and Judith Hanson Lasater. Sign up today at judithhansonlasater.com/yj.

0 notes

Text

How to Keep Your Knees Safe and Injury-Free During a Yoga Class

Exploring how your knees move can lead to a balanced relationship between stability and vulnerability, on and off the mat.

Anatomy of the knee

In 2007, I slipped while descending a steep trail in Shenandoah National Park. I took a hard blow to the outside of my left knee, shredding the lateral meniscus and articular cartilage and dislocating the kneecap. I faced major surgeries to save the knee from a partial joint replacement. My orthopedic surgeon was upfront: Recovery would be long and arduous. More than anything else, my mindset would be the key to my healing. That meant I needed to cultivate a nurturing relationship with my knees.

Fortunately, prior to the accident I’d been a yoga practitioner with a daily meditation habit for 19 years. Before surgery, I dedicated an hour a day to channeling love and gratitude into my knees. By the time I was wheeled into the operating room for the first of two surgeries that ultimately restored the joint’s structure, the knee had become my most beloved body part. I had learned to celebrate its complexity and vulnerability, and to fine-tune movements to treat it well. The knee is the body’s nexus of faith and duty: One of the first things we do when we seek strength or mercy is get down on our knees. We also drop to our knees when we pledge ourselves to a path of devotion. Each knee is the grand arbiter of mechanical forces received from the foot and hip. For better or worse, the knee adjusts itself to balance and transmit the energies of impact, shear (sliding forces), and torsion (twisting forces).

See also Essential Foot and Leg Anatomy Every Yogi Needs to Know

The knee is often described as a hinge joint, but that’s not the whole story. To the eye, it resembles a hinge because its primary movements are flexion (bending, to draw the thigh and calf toward each other) and extension (straightening, to move the thigh and calf away from each other). In reality, the knee is a modified hinge joint. It glides, and rotates. This makes it more versatile but also more vulnerable. Its range of motion becomes clear when you compare it with the elbow. Bend and straighten your elbow several times. The movement feels similar to opening and closing a laptop. Try it again by moving between Plank Pose and Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose). Now try Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose II), placing your front hand on the inner part of your front knee. Bend your front knee (flexion) and feel the thigh bone, or femur, glide forward and rotate—moving the knee up and out. Straighten your knee (extension) and feel the femur glide backward and rotate—moving the knee down and in.

To keep stable, the knee relies on tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the joint capsule itself, not large muscles. Among standing yoga poses, Tadasana (Mountain Pose) is most stable for the knee because there is maximal contact between the end of the femur and tibial plateau (the top of the tibia, or shin bone). Things go awry, though, if you “lock” your knees. When we hyperextend—and many of us do so without conscious thought—we excessively squeeze the anterior, or frontal, aspect of the menisci (see drawing), pushing the tissues backward, out of their natural placement. Instead, practice standing with your knees in a “relaxed straight”: stand and press back through one of your knees. Then firm your calf muscles toward your shin bone. Notice how all your leg muscles engage. Take your attention to the middle of your knee. It should feel very stable. Practicing this action over time will reeducate your muscles and correct hyperextension. Also, the inner parts of the knee are larger, thicker, and deeper than the outer parts. This anatomical asymmetry makes it normal for the kneecaps to slightly glance toward each other in poses such as Tadasana and Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose). Perhaps you’ve heard the cue to point your kneecaps directly forward in straight-leg asana? Don’t do it; it can injure the knee because it overrides the structure and function of the joint.

See also Anatomy 101: Are Muscular Engagement Cues Doing More Harm Than Good?

The knee is least stable when bent. When we flex our knees, as in Virabhadrasana II, we have less contact between the femur and tibia. When there is less bony contact, connective tissues strain and become more vulnerable. The vastus medialis, the inner muscle of the front thigh, is primarily responsible for keeping the patella, or kneecap, in its femoral sulcus, the groove at the end of the thigh bone. Ideally, we want the kneecap to slide smoothly up and down that groove, so that the patella functions efficiently as a fulcrum when we bend and straighten the knee. But the vastus medialis is much smaller than the vastus lateralis, on the outside of the front thigh. This strength imbalance in the front thigh muscles, or quadriceps, can cause the kneecap to pull out and up, creating pain in everything from walking to bent-leg standing asana. Lunge poses often make it worse. But we can develop balance between the muscles through “quad setting.” Sit in Dandasana (Staff Pose) with a rolled towel under your knees, toes pointed up. Press out through your heels. Then, press down through your knees, leading with the inner knee. Hold for 10-20 seconds, release, and repeat to fatigue.

Remember, the knees, stuck in the middle, absorb energy from the feet and hips. If you take them beyond normal rotation or put too much pressure on them when bent, you increase the risk of harming your ACL. In turn, several poses demand a high degree of caution. Some I’ve stopped practicing altogether.

Bhekasana (Frog Pose): Places strain on the ACL and medial meniscus because of torsion from trying to draw the soles down and toward the outer hips.

Virasana (Hero Pose): When practiced with the knees together and feet outside the hips, we push maximal range of motion for most people and add rotational strain multiplied by body weight.

Padmasana (Lotus Pose): Without sufficient mobility in the hips (and some of us will never have it due to our particular anatomy), our knees twist too much. The primary axis of movement in the body is the hips, a true ball-and-socket joint uniquely suited to rotation.

Pasasana (Noose Pose): Without sufficient strength in the hamstrings and calves, gravity wins, putting undue pressure on the knees, which strains the ACL. Laxity in the ACL can reduce power and stability in the knee.

Now that I’ve laid out what to avoid, here is what I recommend. Try this homework for two weeks to get to know your knees.

See also Fascial Glide Exercise for Functional Quads and Healthy Knees

Take a Good Look at Your Knees

If healthful for you, take Adho Mukha Svanasana, and look at your knees. Notice that the inner knees naturally move back farther than the outer knees and the kneecaps glance toward each other. Remember: This is normal!

Gain Knowledge about the Knee Muscles

Sit in Dandasana. With relaxed thighs, lightly grasp the inner and outer edges of your patellae and wiggle them side to side. Lightly grasp the upper and lower edges of your patellae and gently slide them up and down. Next, engage your thighs. Notice how the patellae cinch into the ends of the femurs. The moral of this story? Use your muscles, instead of mobility, to move your knees in asana.

Show Those Knees from Gratitude!

Rest your hands on your knees and send them love. They do so much for you amid so many demands. Show ’em gratitude! When a body part hurts or doesn’t do what we think it should, we often believe it has failed us. More likely, we have failed our body part by blaming or ignoring it. Gratitude is the antidote to shifting that relationship.

See also Practice These Yoga Exercises to Keep Your Knees Healthy

Yoga Knee Anatomy 101

Avoid injury by understanding how connective tissues help knees move, bear weight, and respond to strain.

Meniscus: Pads the space between the femur and tibia. This C-shaped structure also deepens the tibial plateau and helps stabilize the knee, especially the medial meniscus, which firmly attaches to the joint capsule and resists shear and rotation. Each knee has two menisci.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Functions like a stiff bungee cord to keep tibia from sliding too far ahead of femur. It’s one of the most commonly injured parts of the knee due to twisting actions that overstretch or tear it. That means many yoga poses put it at risk.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Keeps the knee from buckling inward. Also works with the ACL to stop the tibia from sliding too far forward. The MCL typically gets injured in sports with heavy physical contact and sudden changes in direction, such as football. It is not commonly injured in asana, though avoid “knee drift” toward the midline of the body in bent-leg asana; when the knee is in flexion, center the kneecap toward the space between the second and third toes.

See also Anatomy 101: Why Anatomy Training is Essential for Yoga Teachers

About our expert

Mary Richards, MS, C-IAYT, ERYT, YACEP, has been practicing yoga for almost 30 years and travels around the country teaching anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. A hard-core movement nerd and former NCAA athlete, Mary has a master’s degree in yoga therapy.

Learn more Study Experiential Anatomy online with Mary and Judith Hanson Lasater. Sign up today at judithhansonlasater.com/yj.

0 notes