#saskatchewan light infantry

Text

"Ted Taylor Would Serve," Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. June 21, 1941. Page 3.

-----

13-Year-Old Eldersley Boy Wants to Join Forces As Drummer

----

Stout young hearts beat fast these days as they hear the roll of drums and see their elder brothers and their fathers marching off to war. They want to play their part in serving their country's need. That general keenness of youngsters to share responsibility is reflected in the purchase of war savings stamps throughout the winter and the pledge of many to continue such savings through the holidays.

But a letter has come to the desk of Lt.-Col. Roy MacMillan, 2nd Battalion S.L.I., which tells this story better than any figures on war savings stamps. It was from a 13-year-old boy in Eldersley, Sask., and read simply:

"Dear Sir:

"I would like a position in the army, navy or air force as a drummer boy or anything else a boy could do. My age is 13, June 12, my height is 4 feet, 2 inches, weight 97 pounds. I feel I can't do enough towards the war. I can't make enough money to buy war savings stamps. So if I could get a job to do something in the forces I would be glad. We are out of school and on our holidays.

Yours truly,

TED TAYLOR."

#saskatoon#eldersley sask#drummer boy#child soldier#military enlistment#saskatchewan light infantry#canadian army#home front#youth in revolt#history of canadian youth#canada during world war 2

0 notes

Text

On 17th August 2010 Bill Millin, piper to Lord Lovat at D Day, died, aged 88.

Born on 14th July 1922 Saskatchewan, Canada to a father of Scottish origin who moved the family to Canada but returned to Glasgow as a policeman when William was three. He grew up and went to school in the Shettleston are of the city. He joined the Territorial Army in Fort William, where his family had moved, and played in the pipe bands of the Highland Light Infantry and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders before volunteering as a commando and training with Lovat at Achnacarry along with French, Dutch, Belgian, Polish, Norwegian, and Czechoslovakian troops.

Lord Lovat had appointed his personal piper during commando training at Achnacarry, and was the only man during the D Day landing who wore a kilt – it was the same Cameron tartan kilt his father had worn in Flanders during World War I – and he was armed only with his pipes and the sgian-dubh sheathed inside his kilt-hose on the right side.

Taken from accounts of 6th June 1944 on Sword Beach Normandy.

Bill began his apparently suicidal serenade immediately upon jumping from the ramp of the landing craft into the icy water on D Day. As the Cameron tartan of his kilt floated to the surface he struck up with Hieland Laddie. He continued even as the man behind him was hit, dropped into the sea and sank.Once ashore Millin did not run, but walked up and down the beach, blasting out a series of tunes. After Hieland Laddie, Lovat, the commander of 1st Special Service Brigade (1 SSB), raised his voice above the crackle of gunfire and the crump of mortar, and asked for another. Millin strode up and down the water’s edge playing The Road to the Isles.

Bodies of the fallen were drifting to and fro in the surf. Soldiers were trying to dig in and, when they heard the pipes, many of them waved and cheered — although one came up to Millin and called him a “mad bastard”.His worst moments were when he was among the wounded. They wanted medical help and were shocked to see this figure strolling up and down playing the bagpipes. To feel so helpless, Millin said afterwards, was horrifying. For many other soldiers, however, the piper provided a unique boost to morale. “I shall never forget hearing the skirl of Bill Millin’s pipes,” said one, Tom Duncan, many years later. “It is hard to describe the impact it had. It gave us a great lift and increased our determination. As well as the pride we felt, it reminded us of home and why we were there fighting for our lives and those of our loved ones.”

When the brigade moved off, Millin was with the group that attacked the rear of Ouistreham. After the capture of the town, he went with Lovat towards Bénouville, piping along the road.

They were very exposed, and were shot at by snipers from across the canal. Millin stopped playing. Everyone threw themselves flat on the ground — apart from Lovat, who went down on one knee. When one of the snipers scrambled down a tree and dived into a cornfield, Lovat stalked him and shot him. He then sent two men into the corn to look for him and they came back with the corpse. “Right, Piper,” said Lovat, “start the pipes again.”

At Bénouville, where they again came under fire, the CO of 6 Commando asked Millin to play them down the main street. He suggested that Millin should run, but the piper insisted on walking and, as he played Blue Bonnets Over the Border, the commandos followed.

When they came to the crossing which later became known as Pegasus Bridge, troops on the other side signalled frantically that it was under sniper fire. Lovat ordered Millin to shoulder his bagpipes and play the commandos over. “It seemed like a very long bridge,” Millin said afterwards.

The pipes were damaged by shrapnel later that day, but remained playable. Millin was surprised not to have been shot, and he mentioned this to some Germans who had been taken prisoner.They said that they had not shot at him because they thought he had gone off his head.

The pictures shows Millin playing at Edinburgh Castle in 2001, on Sword beach, 1994 and his statue there which was unveiled in 2013.

128 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

NAMES AND TIMELINES.... #honour #WeRemember #shouldertoshoulder #freedom #liberty #educationforall #equality - Canada’s 158 fallen and brought home #HighwayOfHeroes

Remembering Canada's son's and daughters.... and all those beautiful Canadian children we have lost..... and to our 6,000 wounded.... we got your backs.... of that you can be sure.... no political games on this one... we will ensure it gets fixed... and fast..... God bles you all.- and all our Nato Coalition Sons and Daughters from 47 countries.... we are still here.... each and every day..

158 Canadian soldiers, two aid workers, one journalist and one diplomat have been killed since the Canadian military deployed to Afghanistan in early 2002.

CANADA: Timeline: Death toll in Afghanistan 2013

Master Corporal Byron Garth Greff Age: 28 Deceased: October 29, 2011 Unit: 3rd Battalion Princess Patricias's Canadian Light Infantry Hometown: Swift Current, Saskatchewan Incident: Improvised explosive device, Kabul, Afghanistan

Deceased: June Francis Roy Deceased: May 27, 2011: Bombardier Karl Manning; Hometown: 5th Régiment d'artillerie légère du Canada of the 1er Royal 22e Régiment Battle GroupIncident: Non combat related

Deceased: March 28, 2011: Corporal Yannick Scherrer : 24 of Montreal, Quebec: 1st Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment, based in CFB Valcartier in Quebec: Yannick's First tour,Nakhonay, southwest of Kandahar City

Deceased: December 18, 2010: Corporal Steve Martin -Age: 24-Hometown: St-Cyrille-de-Wendover (Québec)-Unit: 3e Bataillon, Royal 22e Régiment-Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan.

Deceased February 10, 2010- at home but still on active duty to Afghanistan- Captain Francis (Frank) Cecil Paul to the official list of Canadian Forces (CF) casualties sustained in support of the mission in Afghanistan. Capt Paul died in Canada last February while on leave from Kandahar.

Deceased: August 30, 2010 Corporal Brian Pinksen, Age: 21, Hometown: Corner Brook , Newfoundland and Labrador ,Unit: 2nd Battalion , Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan. Deceased: July 20, 2010 Sapper Brian Collier Age: 24 Hometown: Bradford, Ontariom Unit: 1 Combat Engineer Regiment Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan Deceased: June 26, 2010 Master Corporal Kristal Giesebrecht Age: 34 Hometown:Wallaceburg, Ontario.Unit: 1 Canadian Field Hospital Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan Deceased: June 26, 2010 Private Andrew Miller Age: 21 Hometown: Sudbury, Ontario Unit: 2 Field Ambulance Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan. Deceased: June 21, 2010 Sergeant James Patrick MacNeil Age: 29 Hometown: Glace Bay, Nova Scotia Unit: 2 Combat Engineer Regiment Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan. Deceased: June 6, 2010 Sergeant Martin Goudreault Age: 35 Hometown: Sudbury, Ontario Unit: 1 Combat Engineer Regiment Incident: Improvised explosive device, Panjwa'i District, Afghanistan. Deceased: May 24, 2010Trooper Larry Rudd Age: 26 Hometown: Brantford, Ontario Unit: Royal Canadian Dragoons Incident: Improvised explosive device, southwest of Kandahar City, Afghanistan. Deceased: May 18, 2010Colonel Geoff Parker Age: 42 Hometown: Oakville, Ont.Unit: Land Forces Central Area Headquarters Incident: Suicide bomber, Kabul, Afghanistan May 13 Pte. Kevin Thomas McKay, 24, was killed by a homemade landmine while on a night patrol near the village of Nakhoney, 15 southwest of Kandahar City. May 3 Petty Officer Second Class Douglas Craig Blake, 37, was on foot with other soldiers around 4:30 p.m. Monday near the Sperwan Ghar base in Panjwaii district when an improvised explosive device detonated. Apr 11 Private Tyler William Todd, 26, originally from Kitchener, Ont., was killed when he stepped on an improvised explosive device while taking part in a foot patrol in the district of Dand, about eight kilometres southwest of Kandahar City. Mar 20 Corporal Darren James Fitzpatrick, a 21-year-old infantryman from Prince George, B.C., succumbed to wounds received from a roadside bomb that detonated during a joint Canadian-Afghan mission 25 kilometres west of Kandahar City. Feb. 12 Corporal Joshua Caleb Baker, a 24-year-old Edmonton-based soldier died in an explosion during a "routine" training exercise at a range four kilometres north of Kandahar City. Jan. 16 Sergeant John Wayne Faught, a 44-year-old section commander from Delta Company, 1 Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry of Edmonton. Faught was killed when a land mine exploded underneath him while he led a foot patrol near the village of Nakhoney, about 15 kilometres southwest of Kandahar City. 2009 Dec. 30 Private Garrett William Chidley, 21, of Cambridge, Ont.; Corporal Zachery McCormack, 21, of Edmonton; Sergeant George Miok, 28, of Edmonton; Sergeant Kirk Taylor, 28, of Yarmouth, N.S.; and Canwest journalist Michelle Lang of Calgary. All were killed when a massive homemade land mine blew up under the light-armoured vehicle that was carrying them on a muddy dirt road on Kandahar City's southern outskirts. Dec. 23 Lieut. Andrew Richard Nuttall, 30, originally from Prince Rupert, B.C., was serving with the Edmonton-based 1st Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. died when a homemade bomb detonated as he led a foot patrol in the dangerous Panjwaii district southwest of Kandahar City. Oct. 30 Sapper Steven Marshall, 24, a combat engineer with the 11th Field Squadron, 1st Combat Engineer Regiment had been in Afghanistan less than one week when he stepped on a homemade landmine while on patrol in Panjwaii District about 10 kilometres southwest of Kandahar City. Oct. 28 Lt. Justin Garrett Boyes, 26, from the Edmonton-based, 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry was killed by a homemade bomb planted while on patrol with Afghan National Police near Kandahar City. Sep. 17 Private Jonathan Couturier, 23, of Loretteville, Que., with the 2nd Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment, died when an armoured vehicle struck an improvised explosive device about 25 kilometres southwest of Kandahar City in Panjwaii district. Eleven other soldiers suffered slight injuries. Sep. 13 An armoured vehicle struck an improvised explosive device near Kandahar City, killing Pte. Patrick Lormand, 21. Four other soldiers from 2nd Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment received minor injuries in the blast. Sep. 6: Major Yannick Pepin, 36, of Victoriaville, Que., commander of the 51st Field Engineers Squadron of the 5th Combat Engineers, and Cpl. Jean-Francois Drouin, 31, of Quebec City, who served with the same unit, were killed and five other Canadians were injured when their armoured vehicle struck an improvised explosive device in Dand District, southwest of Kandahar City. Aug 1: Sapper Matthieu Allard, 21, and his close friend, Cpl. Christian Bobbitt, 23, were killed near Kandahar City by an improvised explosive device when they got off their armoured vehicle to examine damage to another vehicle in their resupply convoy that had been hit by another IED. Both men served with the 5th Combat Engineers Regiment from Valcartier, Que. Jul 16: Private Sebastien Courcy, 26, of St. Hyacinthe, Que., with the Quebec-based Royal 22nd Regiment was killed when he fell from "a piece of high ground" during a combat operation in the Panjwaii District. Jul. 6: Two Canadian soldiers were killed in southern Afghanistan when the Griffon helicopter they were aboard crashed during a mission. Master Cpl. Pat Audet, 38, from the 430 tactical helicopter squadron; and Cpl. Martin Joannette, 25, from the third battalion of the Royal 22nd Regiment, both based in Valcartier, Que. Jul. 4: Master Cpl. Charles-Philippe Michaud, 28, died in a Quebec City hospital from injuries he sustained after stepping on a landmine while on foot patrol June 23. Jul. 3: Corporal Nicholas Bulger, 30, hailed from Peterborough, Ont., and was with the Edmonton-based 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. The convoy which transports Canada's top soldier in Afghanistan hit a roadside bomb, killing Bulger who was a member of the general's tactical team and injuring five others. Jun. 14: Corporal Martin Dubé, 35, from Quebec City, Quebec with the 5 Combat Engineer Regiment killed by an improvised explosive device, in the Panjwayi District of Afghanistan. Jun. 8: Private Alexandre Péloquin, 20, of Brownsburg-Chatham, Quebec with 3rd Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment. Was killed by an improvised explosive device, Panjwayi District, Afghanistan. Apr. 23: Major Michelle Mendes, based in Ottawa, Ont. was found dead in her room at the Kandahar Airfield in Afghanistan. Apr. 13: Trooper Karine Blais, 21, with the 12th Armoured Regiment based in Val Cartier, Que., was killed in action when her vehicle was hit by a homemade bomb. Mar. 20: Master Cpl. Scott Vernelli of the 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, and Pte. Tyler Crooks of 3rd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, died when they were hit by an IED while on a foot patrol in western Zahri District as part of Operation Jaley. An Afghan interpreter was also killed. Five other soldiers from November Company were wounded as was another Afghan interpreter. About two hours later, Trooper Jack Bouthillier and Trooper Corey Hayes from a reconnaissance squadron of the Petawawa-based Royal Canadian Dragoons died when their armoured vehicle struck an IED in Shah Wali Khot District about 20 kilometres northeast of Kandahar. Three other Dragoons were wounded in the same blast. Mar. 8: Trooper Marc Diab, 22, with the Royal Canadian Dragoons based in Petawawa was killed by a roadside bomb north of Kandahar City. Mar. 3: Warrant Officer Dennis Raymond Brown, a reservist from The Lincoln and Welland Regiment, based in St. Catharines, Ont., Cpl. Dany Olivier Fortin from the 425 Tactical Fighter Squadron at 3 Wing, based in Bagotville, Que., and Cpl. Kenneth Chad O'Quinn, from 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group Headquarters and Signals Squadron, in Petawawa, Ont., were killed when an IED detonated near their armoured vehicle northwest of Kandahar. Jan. 31: Sapper Sean Greenfield, 25, was killed when and IED hit his armoured vehicle while driving in the Zhari district, west of Kandahar. He was with the 2 Combat Engineer Regiment based in Petawawa. Jan. 7: Trooper Brian Richard Good, 42, died when the armoured vehicle he was traveling in was struck by an improvised explosive devise, or IED. Three other soldiers were injured in the blast, which occurred around 8 a.m. in the Shahwali Kot district, about 35 kilometres north of Kandahar City. 2008 Dec. 27: Warrant Officer Gaetan Joseph Maxime Roberge and Sgt. Gregory John Kruse died in a bomb blast while they were conducting a security patrol in the Panjwaii district, west of Kandahar City. Their Afghan interpreter and a member of the Afghan National Army were also killed. Three other Canadian soldiers were injured in the blast. Dec. 26: Private Michael Bruce Freeman, 28, was killed after his armoured vehicle was struck by an explosive device in the Zhari dessert, west of Kandahar City. Three other soldiers were injured in the blast. Dec. 13: Three soldiers were killed by an IED west of Kandahar City after responding to reports of people planting a suspicious object. Cpl. Thomas James Hamilton, 26, Pte. John Michael Roy Curwin, 26, and Pte. Justin Peter Jones, 21, members of 2nd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment from CFB Gagetown, N.B., died. Dec. 5: An IED kills W.O. Robert Wilson, 38, Cpl. Mark McLaren, 23, and Pte. Demetrios Diplaros, 25, all members of the 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment based in Petawawa, Ont. All three are from Ontario - Keswick, Peterborough and Scarborough respectively. Sep. 7: Sergeant Prescott (Scott) Shipway, 36, was killed by an IED just days away from completing his second tour of Afghanistan and on the same day the federal election is called. Shipway, a section commander with 2nd battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry based out of Winnipeg, was killed in the Panjwaii district. He is from Saskatchewan. Sep. 3: Corporals Andrew (Drew) Grenon, 23, of Windsor, Ont., and Mike Seggie, 21, of Winnipeg and Pte. Chad Horn, 21, of Calgary, infantrymen with the 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry from CFB Shilo, where killed in a Taliban ambush. Five other soldiers were injured in the attack. Aug. 20: Three combat engineers attached to 2nd Battalion Batallion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in Edmonton are killed by an IED in Zhari district. Sgt. Shawn Eades, 34, of Hamilton, Ont., Cpl. Dustin Roy Robert Joseph Wasden,25, of the Spiritwood, Sask., area, and Sapper Stephan John Stock, 25, of Campbell River, B.C. A fourth soldier was seriously injured. Aug. 13: Jacqueline Kirk and Shirley Case, who were in Afghanistan with the International Rescue Committee, died in Afghanistan's Logar province after the car they were riding in was ambushed. Kirk, 40, was a dual British-Canadian citizen from Outremont, Que. Case, 30, was from Williams Lake, B.C. Aug. 11: Master Cpl. Erin Doyle, 32, of Kamloops, B.C., an Edmonton-based soldier of 3rd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was killed in a firefight in Panjwaii district. Aug. 9: Master Cpl. Josh Roberts, 29, a native of Saskatchewan and a member of 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry based in Shilo, Man., died during a firefight involving a private security company in the Zhari district, west of Kandahar City. The death is under investigation. Jul. 18: Corporal James Hayward Arnal of Winnipeg, an infantryman with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was rushed from the patrol in the volatile Panjwaii district to Kandahar Airfield, where he died from his injuries sustained from an IED. Jul. 5: Private Colin William Wilmot, a medic with 1 Field Ambulance and attached to 2nd Battalion Batallion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry from Edmonton, stepped on an IED while on foot patrol in the Panjwaii district. Jul. 4: Corporal Brendan Anthony Downey died at Camp Mirage in an undisclosed country in the Arabian Peninsula of non-combat injuries. He was in his quarters at the time. Downey, 36, was a military police officer with 17 Wing Detachment, Dundurn, Sask. Jun. 7: Captain Jonathan Sutherland Snyder, a member of 1 Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry based in Edmonton, died after falling into a well while on a security patrol in the Zhari district. Jun. 3: Captain Richard Leary, 32, was killed when his patrol came under small arms fire while on foot patrol west of Kandahar City. Leary, "Stevo" to his friends, and a member of 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was based at CFB Shilo, Man. May 6: Corporal Michael Starker of the 15 Field Ambulance was fatally wounded during a foot patrol in the Pashmul region of the Afghanistan's Zhari district. Starker, 36, was a Calgary paramedic on his second tour in Afghanistan. He was part of a civil-military co-operation unit that did outreach in local villages. Another soldier, who was not identified, was wounded in the incident. Apr. 4: Private Terry John Street, of Surrey, B.C., and based with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in Shilo, Man., was killed when his armoured vehicle hit an improvised explosive device to the southwest of Kandahar City. Mar. 16: Sergeant Jason Boyes of Napanee, Ont., based with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in Shilo, Man., was killed when he steps on a buried explosive device while on foot patrol in the Zangabad region in Panjwaii District. Mar. 11: Bombardier Jeremie Ouellet, 22, of Matane, Que., died in his quarters at Kandahar Airfield. He was with the 1st Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery. His death is under investigation by the National Investigative Service. Mar. 2: Trooper Michael Yuki Hayakaze, 25, of Edmonton was killed by an IED just days before his tour was scheduled to end. He was in a vehicle about 45 kilometres west of the Kandahar base. He was a member of the Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians). Jan. 23: Sapper Etienne Gonthier, 21, of St-George-de-Beauce, Que., and based with 5e Regiment du genie de combat in Val Cartier, Que. was killed and two others wounded in an incident involving a roadside bomb. Jan. 15: Trooper Richard Renaud from Alma, Que., was killed and a second Canadian soldier was injured when their armoured vehicle hit a roadside bomb Tuesday in Kandahar's Zhari district. Renaud, 26, of the 12eme Regiment blinde du Canada in Valcartier, Que., and three other soldiers were on a routine patrol in the Arghandab region, about 10 Kilometres north of Kandahar City, when their Coyote reconnaissance vehicle struck the improvised explosive device. Jan. 6: Corporal Eric Labbe, 31, of Rimouski, Que., and W.O. Hani Massouh died when their light armoured vehicle rolled over in Zhari district. 2007 Dec. 30: Gunner Jonathan Dion, 27, a gunner from Val d'Or, Que., died and four others were injured after their armoured vehicle hit a roadside bomb in Zhari district. Nov. 17: Corporal Nicholas Raymond Beauchamp, of the 5th Field Ambulance, and Pte. Michel Levesque, of the Royal 22nd Regiment, both based in Valcartier, Que., were killed when a roadside bomb exploded near their LAV-III armoured vehicle in Zhari district. Sep. 25: Corporal Nathan Hornburg, 24, of the Kings Own Calgary Regiment, was killed by mortar fire while trying to repair the track of a Leopard tank during an operation in the Panjwaii district. Aug. 29: Major Raymond Ruckpaul, serving at the NATO coalition headquarters in Kabul, died after being found shot in his room. ISAF and Canadian officials have said they had not ruled out suicide, homicide or accident as the cause of death. Ruckpaul was an armoured officer based at the NATO Allied Land Component Command Headquarters in Heidelberg, Germany. His hometown and other details have not been released. Aug. 22: Two Canadian soldiers were killed by a roadside bomb. M.W.O. Mario Mercier of 2nd Battalion Batallion, Royal 22nd Regiment, based in Valcartier, Que., and Master Cpl. Christian Duchesne, a member of Fifth Ambulance de campagne, also based in Valcartier, died when the vehicle they were in struck a suspected mine, approximately 50 kilometres west of Kandahar City during Operation EAGLE EYE. An Afghan interpreter was also killed and a third soldier and two Radio Canada journalists were injured. Aug. 19: Private Simon Longtin, 23, died when the LAV-III armoured vehicle he was travelling in struck an improvised explosive device. Jul. 4: Six Canadian soldiers were killed when a roadside bomb hit their vehicle. The dead are Capt. Matthew Johnathan Dawe, Cpl. Cole Bartsch, Cpl. Jordan Anderson and Pte. Lane Watkins, all of 3rd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, based in Edmonton, and Master Cpl. Colin Bason, a reservist from The Royal Westminster Regiment and Capt. Jefferson Clifford Francis of 1 Royal Canadian Horse Artillery based in Shilo Man. Jun. 20: Three soldiers from 3rd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, died when their vehicle was struck by an improvised explosive device. Sgt. Christos Karigiannis, Cpl. Stephen Bouzane, 26, and Pte. Joel Wiebe, 22 were on a re-supply mission, travelling between two checkpoints in an open, all-terrain vehicle, not an armoured vehicle. Jun. 11: Trooper Darryl Caswell, 2nd Battalion Royal Canadian Dragoons, was killed by a roadside bomb that blew up near the vehicle hewas travelling in, while on patrol about 40 minutes north of Kandahar city. He was part of a resupply mission. May 30: Master Cpl. Darrell Jason Priede, a combat cameraman, died when an American helicopter he was aboard crashed in Afghanistan's volatile Helmand province, reportedly after being shot at by Taliban fighters. Priede was from CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick. May 25: Corporal Matthew McCully, a signals operator from 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group Headquarters and Signals Squadron, based at Petawawa, Ont., was killed while on foot patrol and another soldier was injured when a roadside bomb exploded near them during a major operation to clear out Taliban. The soldier, a member of the mentorship and liaison team, is believed to have stepped on an improvised explosive device. Apr. 18: Master Cpl. Anthony Klumpenhouwer, 25, a special forces member, died from injuries sustained in an accidental fall from a communications tower in Kandahar, Afghanistan. It is the first death of a special forces member while on duty in Afghanistan. Apr. 11: Master Cpl. Allan Stewart, 30, and Trooper Patrick Pentland, 23, were killed by a roadside bomb in southern Afghanistan. Both men were members of the Royal Canadian Dragoons based at CFB Petawawa, Ont. Apr. 8: Six Canadian soldiers died in southern Afghanistan as a result of injuries sustained when the vehicle they were travelling in hit an explosive device. Sgt. Donald Lucas, Cpl. Aaron E. Williams, Cpl. Brent Poland, Pte. Kevin Vincent Kennedy, Pte. David Robert Greenslade, 2nd Battalion The Royal Canadian Regiment, based in Gagetown, N.B. were killed in the blast. Cpl. Christopher Paul Stannix, a reservist from the Princess Louise Fusiliers, based in Halifax, also died. One other soldier was seriously injured. Mar. 6: Corporal Kevin Megeney, 25, a reservist from Stellarton, N.S., died in an accidental shooting. He was shot through the chest and left lung. Megeney went to Afghanistan in the fall as a volunteer with 1st Batallion, Nova Scotia Highlanders Militia. 2006 Nov. 27: Two Canadian soldiers were killed on the outskirts of Kandahar when a suicide car bomber attacked a convoy of military vehicles. Cpl. Albert Storm, 36, of Niagara Falls, Ont., and Chief Warrant Officer Robert Girouard, 46, from Bouctouche, N.B., were members of the Royal Canadian Regiment based in Petawawa, Ont. They were in an armoured personnel carrier that had just left the Kandahar Airfield base when a vehicle approached and detonated explosives. Oct. 14: Sergeant Darcy Tedford and Pte. Blake Williamson from 1st Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment in Petawawa, Ont., were killed and three others wounded after troops in Kandahar province came under attack by Taliban insurgents wielding rocket propelled grenades and mortars, according to media reports. The troops were trying to build a road in the region when the ambush attack occurred. Oct. 7: Trooper Mark Andrew Wilson, a member of the Royal Canadian Dragoons of Petawawa, Ont., died after a roadside bomb or IED exploded under a Nyala armoured vehicle. Wilson was a gunner in the Nyala vehicle. The blast occurred in the Pashmul region of Afghanistan. Oct. 3: Corporal Robert Thomas James Mitchell and Sgt. Craig Paul Gillam were killed in an attack in southern Afghanistan as they worked to clear a route for a future road construction project. Both were members of the Petawawa, Ont.-based Royal Canadian Dragoons. Sep. 29: Private Josh Klukie was killed by an improvised explosive device while he was conducting a foot patrol in a farm field in the Panjwaii district. Klukie, of Thunder Bay, Ont., was serving in the First Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment. Sep. 18: Four soldiers were killed when a suicide bomber riding a bicycle detonated explosives in the Panjwaii area. Cpl. Shane Keating, Cpl. Keith Morley and Pte. David Byers, 22, all members of 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry from Shilo, Man., and Cpl. Glen Arnold, a member of 2 Field Ambulance, from Petawawa, Ont., were killed in the attack that wounded several others. Sep. 4: Private Mark Anthony Graham, a member of 1st Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment, based at CFB Petawawa, Ont., killed and dozens of others wounded in a friendly fire incident involving an American A-10 Warthog aircraft. Graham was a Canadian Olympic team member in 1992, when he raced as a member of the 4 x 400 metre relay team. Sep. 3: Four Canadian soldiers - W.O. Richard Francis Nolan, W.O. Frank Robert Mellish, Sgt. Shane Stachnik and Pte. William Jonathan James Cushley, all based at CFB Petawawa, west of Ottawa, were killed as insurgents disabled multiple Canadian vehicles with small arms fire and rocket-propelled grenades. Nine other Canadians were wounded in the fighting that killed an estimated 200 Taliban members. Aug. 22: Corporal David Braun, a recently arrived soldier with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was killed by a suicide bomber outside the gates of Camp Nathan Smith in Kandahar City. The soldier, in his 20s, was a native of Raymore, Sask. Three other Canadian soldiers were injured in the afternoon attack. Aug. 11: Corporal Andrew James Eykelenboom died during an attack by a suicide bomber on a Canadian convoy that was resupplying a forward fire base south of Kandahar near the border with Pakistan. A medic with the 1st Field Ambulance based in Edmonton, he was in his mid-20s and had been in the Canadian Forces for four years. Aug. 9: Master Cpl. Jeffrey Scott Walsh, based out of Shilo, Man., with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was shot in a friendly fire incident, just days after arriving in Kandahar to begin his tour of duty. He arrived in Kandahar less than a week earlier. Aug. 5: Master Cpl. Raymond Arndt of the Edmonton-based Loyal Edmonton Regiment was killed when a G-Wagon making a supply run collided with a civilian truck. Three other Loyal Edmonton Regiment soldiers were also injured in the crash. Aug. 3: Corporal Christopher Jonathan Reid, based in Edmonton with the 1st Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, was killed in a roadside bomb attack. Later the same day, Sgt. Vaughn Ingram, Cpl. Bryce Jeffrey Keller and Pte. Kevin Dallaire were killed by a rocket-propelled grenade as they took on militants around an abandoned school near Pashmul. Six other Canadian soldiers were injured in the attack. Jul. 22: A suicide bomber blew himself up in Kandahar, killing two Canadian soldiers and wounding eight more; the slain soldiers were Cpl. Francisco Gomez, an anti-armour specialist from the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in Edmonton, who was driving the Bison armoured vehicle targeted by the bomber's vehicle, and Cpl. Jason Patrick Warren of the Black Watch in Montreal. Jul. 9: Corporal Anthony Joseph Boneca, a reservist with the Lake Superior Scottish Regiment based in Thunder Bay, Ont., was killed as Canadian military and Afghan security forces were pushing through an area west of Kandahar City that had been a hotbed of Taliban activity. May 17: Captain Nichola Goddard, a combat engineer with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery and Canada's first female combat death, was killed during battle against Taliban forces in the Panjwaii region, 24 kilometres west of Kandahar. Apr. 22: Four soldiers were killed when their armoured vehicle was hit by a roadside bomb near Gombad, north of Kandahar. They were Cpl. Matthew Dinning, stationed at Petawawa, Ont.; Bombardier Myles Mansell, based in Victoria; Lieut. William Turner, stationed in Edmonton, and Cpl. Randy Payne of CFB Wainwright, Alta. Mar. 28-29: Private Robert Costall was killed in a firefight with Taliban insurgents in the desert north of Kandahar. A U.S. soldier and a number of Afghan troops also died and three Canadians were wounded. Costall was a member of 1st Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, based in Edmonton. An American inquiry, made public in the summer of 2007, determined Costall was killed by friendly fire. Mar. 5: Master Cpl. Timothy Wilson of Grande Prairie, Alta., succumbed to injuries suffered in the LAV III crash on March 2 in Afghanistan. Wilson died in hospital in Germany. Mar. 2: Corporal Paul Davis died and six others were injured when their LAV III collided with a civilian taxi just west of Kandahar during a routine patrol. The soldiers were with 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. Jan. 15: Diplomat Glyn Berry was killed and three soldiers injured by a suicide bomber in Kandahar. They were patrolling in a G Wagon. 2005 Nov. 24: Private Braun Scott Woodfield, Royal Canadian Regiment, was killed in a traffic accident involving his light-armoured vehicle (LAV III) northeast of Kandahar. Three others soldiers suffered serious injuries. 2004 Jan. 27: Corporal Jamie Murphy died and three soldiers were injured by a suicide bomber while patrolling near Camp Julien in an Iltis jeep. All were members of the Royal Canadian Regiment. 2003 Oct. 2: Sergeant Robert Alan Short and Cpl. Robbie Christopher Beerenfenger were killed and three others injured when their Iltis jeep struck a roadside bomb outside Camp Julien near Kabul. They were from 3rd Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment. 2002 Apr. 18: Sergeant Marc Leger, Cpl. Ainsworth Dyer, Pte. Richard Green and Pte. Nathan Smith were killed by friendly fire when an American fighter jet dropped a laser-guided 225-kilogram bomb on the soldiers during a training exercise near Kandahar. All served with the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry.

0 notes

Text

Army Run is Canada’s run, says Indigenous ambassador

By Steven Fouchard, Army Public Affairs

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan — For Chief Warrant Officer Joel Pedersen, Sergeant Major of the 38 Canadian Brigade Group Battle School and the Indigenous Advisor to the Brigade Commander, the Canada Army Run (CAR) half-marathon is nothing new. In fact, CAR 2019 will be his fourth time participating. What is new is the title he will carry at this year’s event: Indigenous Ambassador.

A few weeks before the 2019 run, which takes place September 22, CWO Pedersen (who will serve as co-Ambassador along with Corporal William Ross from 3rd Battalion Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry), spoke with Canadian Army Public Affairs.

In addition to all things CAR, he discussed what it means to have been the first person from a First Nations Community (Fond du Lac, Saskatchewan) to attain the position of Regimental Sergeant Major of an infantry unit, and the many opportunities that come with being in the Army Reserve.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q1: You've been a marathoner for some time. What drew you to running?

I've enjoyed fitness training, sports and running ever since I was a kid. Running has helped me set goals like completing carrier courses and specialty courses like the jump course and mountain operations, or running the New York Marathon.

Now it’s a part of my lifestyle, and I try to share that with others of all ages and abilities.

Being in the Army we run – it's part of what we do, it’s part of the culture. As far as competitive or distance recreational running, that was through colleagues – non-commissioned officers that were around me. They set an example by being physically and mentally fit.

Q2: How did you feel about being asked to be an Army Run Indigenous Ambassador?

I'm so honoured and grateful. Army Run is one of the top half-marathons in Canada and for the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) it should be on the must-do list.

It is the Army’s half-marathon but it's also Canada's half-marathon.

I find that the running community is similar to the military – there’s a great camaraderie. Because you're sharing a physical challenge whether it's a 5K, 10K or 21K. It's an individual activity and also a group activity with that positive energy.

Q3: How do you plan to approach being an Ambassador?

My approach will be to ensure that everyone knows they are welcome at the Army Run, regardless of age or ability – to inspire and empower as many people as I can through an active and positive healthy lifestyle.

As a First Nations soldier, I hope that others may follow and surpass any of my accomplishments. Running for me is like medicine – it is holistic and natural, it is therapeutic and a tangible physical feeling.

I think of Indigenous soldiers from the First World War like Tom Longboat and Alex Decoteau. Those soldiers were true warrior runners and those gifts helped them accomplish what they had to do.

Private Decoteau was the first Indigenous civilian police officer in Canada – he served with the Edmonton Police and later he was an infantry soldier. I like that example because I served with the Saskatoon Police Service for 25 years, and have had the honour to serve in the CAF now for almost 32 years.

I also think of my friends and colleagues who are no longer able to run, for they also inspire me and motivate me to keep moving forward.

Q4: Are you bringing some family along this year?

Yes, my wife Kim and I are both runners. She and I will be running the half marathon. Our kids are not able to attend this time, but it would be cool to run the distance together someday.

As I mentioned, running for me is like natural medicine. It's always very positive for my mental health. Going for a run is something that we both enjoy doing and it's time that we can spend together.

A run is an opportunity to meditate and clear my mind. I can feel everything around me – the ground under my feet, the air that I’m breathing.

Q5: When did you first join the Army Reserve and what was your inspiration?

I was 17 years old when I joined in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. I was still in high school and I wanted a challenge. My parents had been in the Army Reserve when they were younger and a lot of my family has served, going all the way back to the Boer War and the First World War.

On my mother's side of the family, they fought at Passchendaele, Vimy, and throughout Europe in the Second World War.

The other part of my decision to join was that, at a young age, I knew I wanted to be a police officer, so I felt the military would be a good beginning for that journey.

Now when I talk to soldiers and young officers I tell them, especially if they've just joined the CAF, ‘You have no idea the opportunities that are going to come before you and the doors that are going to open because you've raised your hand and said that you're prepared to serve your country.’ It's a huge privilege and a great honour to be a part of the military.

Q6: You were the first person of First Nations ancestry to serve as Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) of the North Saskatchewan Regiment, and also the Royal Regina Rifles. How did it feel to have achieved those milestones?

I didn’t get there by myself. I had some incredible leaders, family, friends, and colleagues who assisted me when I needed them. The many RSMs who served before me and provided mentorship to me ensured I knew what right looked like.

As a First Nations soldier, it is an opportunity to be a role model that I do not take for granted – to champion other Indigenous soldiers who may not have felt empowered.

Part of my duties now as the RSM of the Battle School, and the Indigenous Advisor to the Brigade Commander, is to ensure all soldiers and leaders are treated with respect.

I heard once that people are not always going to remember what you said, or even what you have done, but they will always remember how you made them feel.

0 notes

Text

Miraumont is a village about 14.5 kilometres north-north-east of Albert and ADANAC Military Cemetery is some 3 kilometres south of the village on the east side of the road to Courcelette (D107). The cemetery is signposted in the centre of Miraumont.

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

ADANAC Military Cemetery

The villages of Miraumont and Pys were occupied on 24-25 February 1917 following the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. They were retaken by the Germans on 25 March 1918, but recovered the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division on the following 24 August. Adanac Military Cemetery (the name was formed by reversing the name “Canada”) was made after the Armistice when graves were brought in from the battlefields and small cemeteries surrounding Miraumont, and particularly from the Canadian battlefields round Courcelette. One grave (Plot IV, Row D, Grave 30) was left in its original position.

ADANAC: Lt R.H.P. Arnholz

ADANAC: Lt R.H.P. Arnholz

ADANAC: Lt A.R.C. Eaton

ADANAC: Lt A.R.C. Eaton

ADANAC: Sgt S. Forsyth VC NZEF

ADANAC: Piper James Richardson VC

ADANAC: Pte J. McArthur

There are now 3,186 Commonwealth burials and commemorations of the First World War in this cemetery. 1,708 of the burials are unidentified but special memorials commemorate 13 casualties known or believed to be buried among them. The cemetery was designed by Sir Herbert Baker.

Number of burials by Unit

Northumberland Fusiliers

64

New Zealand units

64

Royal Warwickshire Regiment

51

16th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Manitoba Regiment)

48

58th Bn. Canadian Inf. (2nd Central Ontario Regiment)

45

3rd Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

41

50th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Alberta Regiment)

41

13th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Quebec Regiment)

39

4th Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

38

Green Howards – Yorkshire Regiment

38

Durham Light Infantry

36

87th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Quebec Regiment)

35

Australian units

34

Lancashire Fusiliers

30

44th Bn. Canadian Inf. (New Brunswick Regiment)

29

Manchester Regiment

29

Royal Field Artillery

29

75th Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

28

Cameron Highlanders

26

Machine Gun Corps – Infantry

26

Border Regiment

25

Gordon Highlanders

25

Bedfordshire Regiment

24

Cheshire Regiment

24

Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders

22

47th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Western Ontario Regiment)

21

29th Bn. Canadian Inf. (British Columbia Regiment)

19

Duke of Wellington – West Riding Regiment

19

West Yorkshire Regiment

19

54th Bn. Canadian Inf. (2nd Central Ontario Regiment)

18

102nd Bn. Canadian Inf. (2nd Central Ontario Regiment)

18

East Surrey Regiment

18

Essex Regiment

18

York & Lancaster Regiment

18

24th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Quebec Regiment)

17

Norfolk Regiment

17

Seaforth Highlanders

17

Royal Naval Division

16

Gloucester Regiment

15

1st Bn. Canadian Pioneers

14

Highland Light Infantry

12

Queen’s – Royal West Surrey Regiment

12

South Staffordshire Regiment

12

46th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Saskatchewan Regiment)

11

Royal Engineers

11

18th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Western Ontario Regiment)

10

38th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Eastern Ontario Regiment)

10

East Lancashire Regiment

10

72nd Bn. Canadian Inf. (British Columbia Regiment)

9

Royal Scots – Lothian Regiment

9

King’s Own Scottish Borderers

8

King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

8

Middlesex Regiment

8

Royal Fusiliers – City of London Regiment

8

Royal West Kent Regiment – Queen’s Own

8

Black Watch – Royal Highlanders

7

31st Bn. Canadian Inf. (Alberta Regiment)

7

67th Bn. Canadian Pioneers

7

Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry

7

Royal Scots Fusiliers

7

28th Bn. (Saskatchewan Regiment)

6

2nd Bn. Canadian Inf. (Eastern Ontario Regiment)

5

11th Brig. Canadian Field Artillery

5

73rd Bn. Canadian Inf. (Royal Highlanders)

5

Hertfordshire Regiment

5

Lincolnshire Regiment

5

24th Bn. London Regiment – The Queen’s

5

Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

5

Royal Berkshire Regiment

5

Cameronians – Scottish Rifles

4

15th Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

4

26th Bn. Canadian Inf. (New Brunswick Regiment)

4

78th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Manitoba Regiment)

4

East Yorkshire Regiment

4

King’s Liverpool Regiment

4

King’s Royal Rifle Corps

4

Sherwood Foresters – Notts. & Derbys Regiment

4

Tank Corps

4

Worcestershire Regiment

4

20th Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

3

22nd Bn. Canadian Inf. (Quebec Regiment)

3

21st Bn. London Regiment First – Surrey Rifles

3

Rifle Brigade

3

Royal Canadian Regiment

3

Royal Welsh Fusiliers

3

19th Bn. Canadian Inf. (1st Central Ontario Regiment)

2

43rd Bn. Canadian Inf. (Manitoba Regiment)

2

Canadian Machine Gun Corps

2

King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

2

Leicestershire Regiment

2

Northamptonshire Regiment

2

Royal Army Medical Corps

2

Royal Irish Regiment

2

Royal Sussex Regiment

2

Somerset Light Infantry

2

5th Bn. Canadian Inf. (CMR, Quebec Regiment)

1

6th Bn. Canadian Machine Gun Corps

1

8th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Manitoba Regiment)

1

14th Bn. Canadian Inf. (Quebec Regiment)

1

21st Bn. Canadian Inf. (Eastern Ontario Regiment)

1

Canadian Army Medical Corps

1

Highland Cyclist Bn.

1

Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

1

Royal Army Service Corps

1

Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force

1

Royal Garrison Artillery

1

Suffolk Regiment

1

South Wales Borderers

1

Identified burials

1473

Unidentified burials: United Kingdom – sailors, soldiers and airmen

1170

Canadian units

512

Australian units

19

New Zealand units

6

Wholly unidentified

5

Total Unidentified burials

1712

Total burials

3185

Silent Cities - WW1 Reviisted website: ADANAC Military Cemetery #Somme #WW1 Miraumont is a village about 14.5 kilometres north-north-east of Albert and ADANAC Military Cemetery is some 3 kilometres south of the village on the east side of the road to Courcelette (D107).

#1916#Courcelette#CWGC#First World War#Great War#Silent Cities#Somme#War Cemetery#WW1 Battlefields#WW1 Revisited

0 notes

Text

One of Scotland's most famous Pipers, Bill Millin was born on July 14th 1922.

Millin was born in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada to a father of Scottish origin who returned to Glasgow as a policeman when Bill was three.

He grew up and went to school in the Shettleston area of the city. He joined the Territorial Army in Fort William, where his family had moved, and played in the pipe bands of the Highland Light Infantry and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders before volunteering as a commando and training with Lovat at Achnacarry along with French, Dutch, Belgian, Polish, Norwegian, and Czechoslovak troops.

There's not really a lot I can add to my previous posts so will leave it to Bill himself to tell you a wee bit more, like this wee snippet "Lovatt asked me if I would march up and down the beach playing 'Road to the Isles', which I did"

In another interview Millin told how even those that disliked the bagpipes, (yes there are some!) admired him, although one called him "a mad bastard"

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On 17th August 2010 Bill Millin, piper to Lord Lovat at D Day, died, aged 88.

Born on 14 July 1922 Saskatchewan, Canada to a father of Scottish origin who moved the family to Canada but returned to Glasgow as a policeman when William was three. He grew up and went to school in the Shettleston are of the city. He joined the Territorial Army in Fort William, where his family had moved, and played in the pipe bands of the Highland Light Infantry and the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders before volunteering as a commando and training with Lovat at Achnacarry along with French, Dutch, Belgian, Polish, Norwegian, and Czechoslovakian troops.

Lord Lovat had appointed his personal piper during commando training at Achnacarry, and was the only man during the D Day landing who wore a kilt – it was the same Cameron tartan kilt his father had worn in Flanders during World War I – and he was armed only with his pipes and the sgian-dubh sheathed inside his kilt-hose on the right side.

Taken from accounts of 6th June 1944 on Sword Beach Normandy.

Bill began his apparently suicidal serenade immediately upon jumping from the ramp of the landing craft into the icy water on D Day. As the Cameron tartan of his kilt floated to the surface he struck up with Hieland Laddie. He continued even as the man behind him was hit, dropped into the sea and sank.Once ashore Millin did not run, but walked up and down the beach, blasting out a series of tunes. After Hieland Laddie, Lovat, the commander of 1st Special Service Brigade (1 SSB), raised his voice above the crackle of gunfire and the crump of mortar, and asked for another. Millin strode up and down the water’s edge playing The Road to the Isles.

Bodies of the fallen were drifting to and fro in the surf. Soldiers were trying to dig in and, when they heard the pipes, many of them waved and cheered — although one came up to Millin and called him a “mad bastard”.His worst moments were when he was among the wounded. They wanted medical help and were shocked to see this figure strolling up and down playing the bagpipes. To feel so helpless, Millin said afterwards, was horrifying. For many other soldiers, however, the piper provided a unique boost to morale. “I shall never forget hearing the skirl of Bill Millin’s pipes,” said one, Tom Duncan, many years later. “It is hard to describe the impact it had. It gave us a great lift and increased our determination. As well as the pride we felt, it reminded us of home and why we were there fighting for our lives and those of our loved ones.”

When the brigade moved off, Millin was with the group that attacked the rear of Ouistreham. After the capture of the town, he went with Lovat towards Bénouville, piping along the road.

They were very exposed, and were shot at by snipers from across the canal. Millin stopped playing. Everyone threw themselves flat on the ground — apart from Lovat, who went down on one knee. When one of the snipers scrambled down a tree and dived into a cornfield, Lovat stalked him and shot him. He then sent two men into the corn to look for him and they came back with the corpse. “Right, Piper,” said Lovat, “start the pipes again.”

At Bénouville, where they again came under fire, the CO of 6 Commando asked Millin to play them down the main street. He suggested that Millin should run, but the piper insisted on walking and, as he played Blue Bonnets Over the Border, the commandos followed.

When they came to the crossing which later became known as Pegasus Bridge, troops on the other side signalled frantically that it was under sniper fire. Lovat ordered Millin to shoulder his bagpipes and play the commandos over. “It seemed like a very long bridge,” Millin said afterwards.

The pipes were damaged by shrapnel later that day, but remained playable. Millin was surprised not to have been shot, and he mentioned this to some Germans who had been taken prisoner.They said that they had not shot at him because they thought he had gone off his head.

The pictures shows Millin playing at Edinburgh Castle in 2001, on Sword beach, 1994 and his statue there which was unveiled in 2013.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's tae us. Wha's like us? Damn few, and they're a'deid.

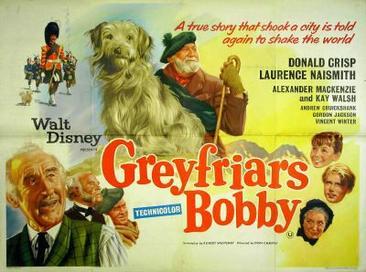

On July 27th 1882 the actor Donald Crisp was born in Aberfeldy, Scotland.

Well the truth is he was born in London, a fact that surprised everyone, the Oscar-winning actor and director enjoyed a career spanning more than 50 years and 400 movies. He was, for a long time, the most famous Scot in Hollywood. Renowned for his distinctive brogue he played a wealth of Scottish characters in popular movies such as The Bonnie Brier Bush, Mary of Scotland, Lassie Come Home, Greyfriars Bobby and many more.

He was clearly a world class actor but his greatest performance was off-screen. Crisp spoke with a soft Scottish burr and maintained throughout his life to have been born in Aberfeldy where he remembered that as a boy his family was so poor they couldn’t afford sugar.

Every so often the actor, who died in 1974, would return to his “homeland” on holiday and recount his days among the hills of Perthshire.

Such was his popularity the Scottish Film Council honoured Crisp and his reported birthplace with a commemorative plaque as part of the Centenary Of Film celebrations and that was when the truth was uncovered.

Librarian Lorna Mitchell began digging into his past and discovered that far from being a Highland laddie Crisp was actually a Cockney, having been born in Bow, East London on 27 July 1882, two years later than the date in most record books. And his real name was George.

It appears the Londoner with no known Scottish connections deliberately developed a Scottish accent to help his career in the hope that it would appeal to movie moguls.

Whatever the reason for his deception Crisp is not alone in elaborating his Scottish connections.

James Robertson Justice, a big man with a voice to match, was a familiar face in British cinema of the 1950s and 1960s, especially for his portrayal as the grumpy surgeon Sir Lancelot Spratt in seven Doctor In The House comedies.

For most of a career that spanned 30 years and 87 movies Justice claimed he was born underneath a whisky distillery on the Isle of Skye. Other versions of his birth claim he was born in Wigtown.

Although he often wore the Robertson tartan proudly it appears he had no legitimate claim to the moniker. He only added it as middle name when he was in his mid-30s because he thought it sounded more Scottish.

In reality Justice was born in Lee, South London, and was brought up in Bromley, Kent.

There is no doubt he was fond of the country. He loved hunting with falcons in the Highlands, was Rector of the University of Edinburgh for two terms, and he lived on and off in the country up until his death in 1975.

Then there’s David Niven, another Londoner, but at least he served in a Scottish army regiment, The Highland Light Infantry.

He also played Bonnie Prince Charlie, a favourite subject on my page, especially with all you Outlander fans!

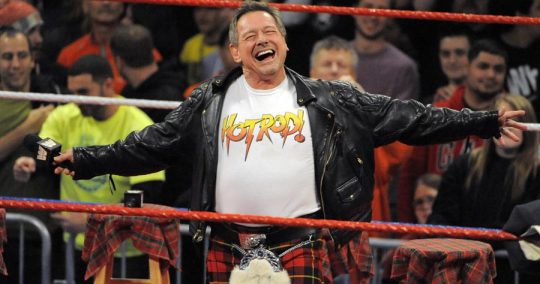

Being Scottish is not just an old trendy thing either, more recently we had the late wrestler ‘Rowdy’ Roddy Piper.

The kilted wrestler was a major star on the wrestling circuit and was billed as coming from Glasgow. He used to enter the ring to bagpipe music and was given the nickname ‘Rowdy’ supposedly due to his trademark ‘Scottish rage’ .Credited as being “the most gifted entertainer in the history of professional wrestling” Piper was actually from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in Canada, although he did have Scottish ancestry.

And it’s not just the stars that have a penchant to claim to be Scottish, enter Dr Scott Peake, at first glance he was Scottish through and through. Born on the island of Raasay, my own ancestral homeland, he had a soft lilting accent, spoke Gaelic, wore tartan trews and Harris Tweed jackets at every opportunity and even claimed to have represented his country internationally in the sports of shinty and cricket.

Having graduated from St Andrew’s University he was teaching classics at a leading private school when, in 2001, he was appointed director of the Saltire Society, promoting Scottish culture to the world.What should have been a crowning moment for any proud Scot turned out to be his downfall. Publicity surrounding his post revealed cracks in his story, not least the fact that nobody on the tiny island of Raasay had heard of him and neither had the governing bodies of shinty and cricket.It finally emerged that Peake was actually an ordinary lad from a council estate in Woolwich, east London. He had adopted his false background while studying at St Andrews in 1991, much to the bemusement of his English family.

Peake was forced to resign from the Saltire Society and was last heard of teaching Latin in a school in Hertfordshire. Even after being unmasked for his pretence ne continued to spin the lie that he was Scottish. When questioned he said "It's a health thing," the lilting Isles brogue still very much in evidence. "I can't talk about it because I'm mentally shot.”

Read more on this wannabe Scot here. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/goodbye-mr-fake-teacher-forced-to-quit-bedales-after-exposure-as-a-serial-fantasist-69755.html

While it may be understandable that the idea of being Scottish could bring on delusions of grandeur some people take it too far. Sometime around 1988 the soft spoken Baron of Chirnside arrived in Tomintoul and began buying up large parts of the village.The Borders aristocrat who claimed his heart belonged in the Highlands was a blessing for the 320 or so inhabitants of the small settlement in the heart of whisky country.

He paid for the police pipe band to play at the Tomintoul Highland games, which he attended in full tartan dress, and he was always happy to give generously to local causes.Over six years it is estimated that ‘Lord’ Tony Williams sunk up to £2 million into the local economy, buying businesses and doing up properties. It is said his businesses employed around 40 people in the village which has a population of around 300.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t his money. The self-styled Laird of Tomintoul, who bought his Baronetcy at auction, turned out to be an accountant from New Malden in Surrey who had embezzled some £5 million from his employer the London Metropolitan Police rather appropriately at Scotland Yard!!!

He was caught only after staff at the Clydesdale Bank in Tomintoul became suspicious of cheques going into the account of Lord and Lady Williams and tipped off the police. He was later jailed for seven years and was last heard of driving a bus in London.

The full sorry story is here https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/double-life-of-laird-at-centre-of-pounds-4m-inquiry-accountant-with-metropolitan-police-adopted-1377515.html

But, perhaps the most famous of wannabe Scots has yet to be born.

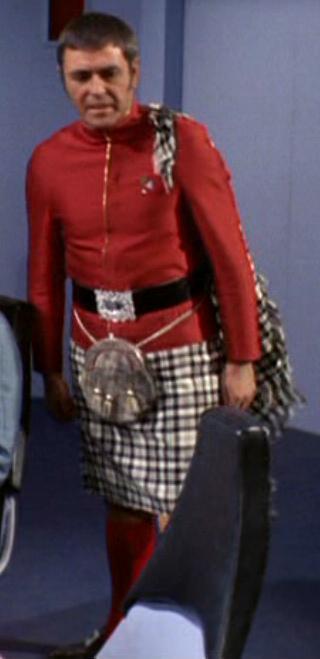

The Annet House Museum in Linlithgow already has a blue plaque on its wall celebrating the town as the birthplace of Montgomery “Scotty” Scott, even though he is not due to enter this world until 2222.

Canadian actor James Doohan, who immortalised the character in the television series Star Trek, claimed to have come up with the Scottish accent of the Starship Enterprise’s chief engineer during a pub crawl in Aberdeen.

However, fans of the show have claimed scripts from the original series suggest Scotty was (or will be) born in Linlithgow on 28 June, 2222 – and that’s enough for the town which is already cashing in on the Trekkie tourist trail with a plaque to commemorate the occasion.

So beware, sometimes all is not what it seems, you never know I might also be a wannabe Scot living in middle England and fooling you all of my Scottish credentials! ;)

#Scotland#Scottish#Donal Crisp#James Robertson Justice#David Niven#Montgomery Scott#Star Trek#Walter Mitty

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

D-Day: Canada’s three services on Operation Overlord

By Chris Charland

The coming storm

In February 1943, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, along with their respective advisors, held a high-level conference in Casablanca, Morocco. They were there to discuss the future conduct of the war.

They decided that plans for the re-entry in to Europe must be given top priority and the concentration of forces and materials needed for the forthcoming invasion began.

In March 1943, United States Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower selected the British Army’s acting Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan as chief of staff to the supreme allied commander of the allied force that would invade northern Europe. Morgan is credited as being the original planner for the invasion of Europe.

Lingering concerns and differences of opinion on Operation Neptune, the assault phase of Operation Overlord, were addressed at the Quebec Conference in August 1943. It was agreed that the invasion of France would take place in May 1944.

On November 28, 1943, General Eisenhower, affectionately known as “Ike”, was appointed the supreme allied commander. His duty was no less than to enter the continent of Europe in conjunction with all other allied nations, undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and destroy its forces. Taking into consideration a nearly full moon and the Normandy tides, June 5, 1944, was set as the day for an invasion on a scale that had never before been attempted.

The entire daring escapade was a monumental logistics nightmare. In all, more than 7,000 vessels carrying more than 150,000 troops would have to cross the English Channel to France undetected and arrive exactly on time to establish a beachhead. Once the details of invasion were coordinated, the land forces, under Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. “Monty” Montgomery, put forth the logistical requirements. All allied air operations would be under the command of the Royal Air Force’s Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory

The build-up also had to provide for the debarkation of reinforcements without interruption for five to six weeks after the landing . . . any delay would carry heavy consequences.

The initial landing was delayed by 24 hours to June 6 due to stormy weather, which also indirectly caused the sinking of the minesweeper USS Osprey. Additionally, an American tank landing craft, United States LCT2498, broke down and subsequently capsized and sank in the vicious swell.

Mother Nature, not the Germans dealt the first blows against Operation Overlord. Nevertheless, D-Day and the Allied forces arrived at the beaches of Normandy with full force on the morning of June 6.

Canadian Red Devils arrive

The crack 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion led by Lieutenant-Colonel G.F.P. Bradbrooke was part of the tough and tumble 3rd Brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division whose members were nicknamed “Red Devils”. The Canadian Red Devils dropped into France after 1 a.m. on June 6, an hour before the arrival of the rest of the brigade, with the aim of securing the DZ (Drop Zone), capturing the enemy headquarters located at the site and destroying the local radio station at Varaville. They were the first Canadian unit to arrive in France.

After that, the Canadians were to destroy vehicle bridges over the Dives River and its tributaries at Varaville. Having done that, they were to neutralize various fortified positions at the crossroads. Additional responsibilities included protecting the left (southern) flank of the 9th Battalion as the battalion assaulted the enemy gun battery at Merville. Upon completing that, the Canadians were to hold a strategically important position at the Le Mesnil crossroads.

Remarkably, the Canadian paratroopers had accomplished all they set out to do by mid-day on June 6.

3rd Division’s Normandy adventure

The Canadian Army’s 3rd Canadian Division, led Major General R.F. “Rod” Keller, along with the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade under the command of Brigadier R.A. Wyman, formed part of General Miles Dempsey’s 2nd British Army.

The Canadians, numbering just over 14,000, came ashore at Juno Beach. The five-mile wide Juno Beach was divided into two primary sectors, Mike and Nan. In turn, each of these was sub-divided into smaller sections denoted by the sector name followed by a colour. Many heroic deeds were performed on the first day at Juno Beach. The Allies had come to expect nothing less. The relentless pursuit of the Canadian Army’s objectives was measured in human currency; of the 14,000 Canadians who stormed Juno Beach, 340 were killed, 574 were wounded and 49 were captured by the defending Germans.

This was a small comfort, considering planners had predicted a much higher casualty rate.

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division* comprised the following units:

7th Canadian Infantry Brigade

Royal Winnipeg Rifles

Regina Rifle Regiment

Canadian Scottish Regiment

8th Canadian Infantry Brigade

Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

Le Régiment de la Chaudière

North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment

9th Infantry Brigade

HIghland Light Infantry of Canada

Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders

Nova Scotia Highlanders

Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (M.G.)

7th Reconnaissance Regiment

17th Duke of York's Royal Canadian Hussars

Divisional Royal Canadian Artillery

12th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

13th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

19th Army Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

Divisional Royal Canadian Engineers

5th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers

6th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers

16th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers

18th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers

3rd Canadian Field Park Company, Royal Canadian Engineers

3rd Canadian Divisional Bridge Platoon, Royal Canadian Engineers

Royal Canadian Corps of Signals

3rd Infantry Divisional Signals

Royal Canadian Army Service Corps

3rd Infantry Divisional Troops Company

Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps

14 Field Ambulance

22 Field Ambulance

23 Field Ambulance

2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade

6th Canadian Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars)

10th Canadian Armoured Regiment (Fort Garry Horse)

27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers)

* Units of the Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers and the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps also provided vital support during the landings.

British units that supported the Canadian landing on Juno Beach

48 Royal Marine Commando

4th Special Service Brigade

26th Assault Squadron

80th Assault Squadron

5th Assault Regiment, Royal Engineers

6th Assault Regiment, Royal Engineers

Two detachments of the 22nd Dragoons, 79th Armoured Division

3rd Battery 2nd Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment

4th Battery, 2nd Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment

“C” Squadron, Inns of Court Regiment

“Ready Aye Ready”

The Royal Canadian Navy was extremely active before and during the first day of Operation Overlord.

A force of 19 corvettes was assigned to provide escort service to the many ships and floating docks heading for assembly points on the south coast of England Eleven frigates, nine destroyers and five corvettes were seconded to the Royal Navy to provide an ASDIC (anti-submarine detection investigation committee) screen around the western approaches to the English Channel one week before the invasion date. This was to guard against the constant German U-Boat threat.

Only hours before the invasion, Canadian “Bangor” Class minesweepers cleared shipping lanes of mines and then ensured that the anchorage swept clear. The last part of their assignment was to sweep the lanes for the assault boats, right to the limit of the deep water. While under a moonlit sky, they crept within a mile and a half (2.4 kilometres) of shore, pretty well under the noses of the unsuspecting Germans.

Fortunately, they were not spotted; German coastal artillery guns would have made mincemeat of them.

The RCN’s two landing ships, HMCS Prince Henry and HMCS Prince David, carried 14 landing craft (LCI or landing craft, infantry) to a point where they could be launched for the run into the beachhead. In the British sector, 30 “Fleet” class destroyers, including HMCS Algonquin and HMCS Sioux, provided direct fire support for the landing craft carrying part of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division after they were launched from the landing ships.

Mines and other underwater obstructions were a constant threat to the landing craft and few escaped without some sort of damage. Leading the second wave were 26 landing craft of the RCN’s 260th, 262nd and 264th Flotillas. These flotillas were carrying a combined force of 4,617 soldiers, primarily from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. Six speedy and deadly MTBs (motor torpedo boat) were assigned to patrol the Seine estuary. RCN corvettes would go on to escort additional convoys into Baie de la Seine during the rest of the day. Naval losses were described as “incredibly light”, especially considering how many enemy long-range naval guns and other weapons were still operational at the time of the landings.

The following RCN vessels took part in the invasion of Normandy:

Tribal class destroyer

HMCS Haida

HMCS Huron

V class destroyer

HMCS Algonquin

HMCS Sioux

River class destroyer (British)

HMCS Gatineau

HMCS Kootenay

HMCS Qu’Appelle

HMCS Ottawa (II)

HMCS Chaudière

HMCS Restigouche

HMCS Skeena

HMCS St. Laurent

Mackenzie Class Destroyer Escort

HMCS Saskatchewan

River class frigate

HMCS Meon

HMCS Teme

River class frigate (1942-1943 program)

HMCS Cape Breton

HMCS Grou

HMCS Matane

HMCS Outremont

HMCS Port Colberne

HMCS Saint John

HMCS Swansea

HMCS Waskesiu

Flower class corvette (1939-1940)

HMCS Alberni

HMCS Baddeck

HMCS Camrose

HMCS Drumheller

HMCS Louisburg (II)

HMCS Lunenburg

HMCS Mayflower

HMCS Moose Jaw

HMCS Summerside

HMCS Prescott

Revised Flower class corvette

HMCS Mimico

Revised Flower class corvette (1940-1941 program)

HMCS Calgary

HMCS Kitchener

HMCS Port Arthur

HMCS Regina

HMCS Woodstock

Revised Flower class corvette (1942-1943 program)

HMCS Lindsay

Troop landing ship

HMCS Prince David

HMCS Prince Henry

Bangor class minesweeper

HMCS Bayfield

HMCS Guysborough

Bangor class minesweeper (1940-1941 regular program)

HMCS Vegreville

Bangor class minesweeper (1941-1942 program)

HMCS Kenora

HMCS Mulgrave

29th Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) Flotilla

MTBs 459, 460, 461, 462, 463, 464, 465 and 466

65th Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) Flotilla

MTBs 726, 727, 735, 736, 743, 744, 745, 747, 748

260th Landing Craft Infantry (Large) Flotilla

LCI(L)s 117, 121, 166, 177, 249, 266, 271, 277, 285, 298 and 301

262nd Landing Craft, Infantry (Large) Flotilla

LCI(L)s 115, 118, 125, 135, 250, 252, 262, 263, 270, 276, 299 and 306

264th Landing Craft, Infantry (Large) Flotilla

LCI(L)s 255, 288, 295, 302, 305, 310 and 311

528th Landing Craft, Assault (LCA) Flotilla

LCAs 736, 850, 856, 925, 1021, 1033, 1371 and 1372

529th Landing Craft, Assault (LCA) Flotilla

LCAs 1957, 1059, 1137, 1138, 1150, 1151, 1374 and 1375

Per Ardua Ad Astra

It was a maximum effort for the crews of Bomber Command’s 6 (RCAF) Group on the night of June 5-6, 1944. A force of 190 aircraft, comprising Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax four-engine heavy bombers, flew 230 sorties in support of pre-invasion operations. A large number of targets were struck, with particular attention paid to the German coastal artillery emplacements on the beachhead. In all, more than 870 tons of high explosives were dropped for the loss of one Canadian Halifax.

RCAF fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons went into action providing support to the Canadian ground forces as the invasion kicked into high gear. The aerial activity over Normandy resembled swarms of locusts—the planes seemed to keep coming with no end in sight. An estimated 1,000 aircraft from 39 of the 42 Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons stationed overseas took on the aerial support of the invasion with roles ranging bombing, air superiority, ground attack and photo reconnaissance.

The following Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons were involved in pre-invasion activities and in support of the actual invasion.

For more information about the squadrons involved in D-Day, their aircraft and their roles, visit “Who was in the air on D-Day?”

SECOND TACTICAL AIR FORCE

No. 83 Group

39 (RCAF) Reconnaissance Wing

400 “City of Toronto” (Fighter Reconnaissance) Squadron

414 “Sarnia Imperials” (Fighter Reconnaissance) Squadron

430 “City of Sudbury” (Fighter Reconnaissance) Squadron

126 (RCAF) Fighter Wing

401 “Ram” (Fighter) Squadron

411 “Grizzly Bear” (Fighter) Squadron

412 “Falcon” (Fighter) Squadron

127 (RCAF) Fighter Wing

403 “Wolf” (Fighter) Squadron

416 “Lynx” (Fighter) Squadron

421 “Red Indian” (Fighter) Squadron

143 (RCAF) Fighter Wing

438 “Wild Cat” (Fighter-Bomber) Squadron

439 “Westmount” (Fighter-Bomber) Squadron

440 “City of Ottawa” (Fighter-Bomber) Squadron

144 (RCAF) Fighter Wing

441 “Silver Fox” (Fighter) Squadron

442 “Caribou” (Fighter) Squadron

443 “Hornet” (Fighter) Squadron

No. 85 Group

142 (Night Fighter) Wing

402 “City of Winnipeg” (Fighter) Squadron

148 (Night Fighter) Wing (RAF)

409 “Nighthawk” (Night Fighter) Squadron

149 (Night Fighter) Wing (RAF)

410 “Cougar” (Night Fighter) Squadron

AIR DEFENCE OF GREAT BRITAIN

10 Group

406 “Lynx” (Night Fighter) Squadron

11 Group

418 “City of Edmonton” (Intruder) Squadron

ALLIED STRATEGIC AIR FORCE

RAF Bomber Command / 6 (RCAF) Group

408 “Goose” (Bomber) Squadron

419 “Moose” (Bomber) Squadron

420 “Snowy Owl” (Bomber) Squadron

424 “Tiger” (Bomber) Squadron

425 “Alouette” (Bomber) Squadron

426 “Thunderbird” (Bomber) Squadron

427 “Lion” (Bomber) Squadron

428 “Ghost” (Bomber) Squadron

429 “Bison” (Bomber) Squadron

431 “Iroquois” (Bomber) Squadron

432 “Leaside” (Bomber) Squadron

433 “Porcupine” (Bomber) Squadron

434 “Bluenose” (Bomber) Squadron

RAF Bomber Command / 8 (Pathfinder) Group

405 “Vancouver” (Bomber) Squadron

RAF Coastal Command / 15 (General Reconnaissance) Group

422 “Flying Yachtsman” (General Reconnaissance) Squadron

423 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron

RAF Coastal Command / 16 Group

415 “Swordfish” (Torpedo Bomber) Squadron

RAF Coastal Command / 19 (General Reconnaissance) Group

404 “Buffalo” (Coastal Fighter) Squadron

407 “Demon” (General Reconnaissance) Squadron

Conclusion

All in all, Canadian combatants from all three services gave an outstanding account of themselves on the first day of the battle. They would continue to distinguish themselves by dogged determination and selfless acts of heroism, helping write the final chapter and finally closing the book on the Third Reich’s so-called one thousand-year reign.

0 notes

Text

HUNTING BIG BEAR: Bringing The North-West Rebellion To A Close

(Volume 24-09)

By Jon Guttman

Resentment over the failure of the government to live up to their treaty obligations, the Cree rose in armed revolt. The Canadian military response was relentless in its pursuit of the perpetrators.

Although neither as epic nor bloody as the Civil War and the numerous, widespread Indian Wars fought in the United States throughout the 18th century, Canada’s North-West Rebellion of 1885 encapsulated many elements of those tragedies attending its southern neighbour’s westward development. Both nations’ conflicts involved issues of government, nationality, citizenship and justice, as well as the less abstract matter of land ownership.

Even while fighting each other, both Union and Confederate soldiers occasionally had to deal with hostile Native Americans on their frontiers. Likewise, while the Canadian Army fought the Métis, it also had to detach two columns to subdue restive First Nations. As a final parallel touch, on May 10, 1869, the United States completed its first transcontinental railroad and on November 7, 1885, Canada did the same — its progress largely accelerated by the requirements of war.