#rumena buzarovska

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

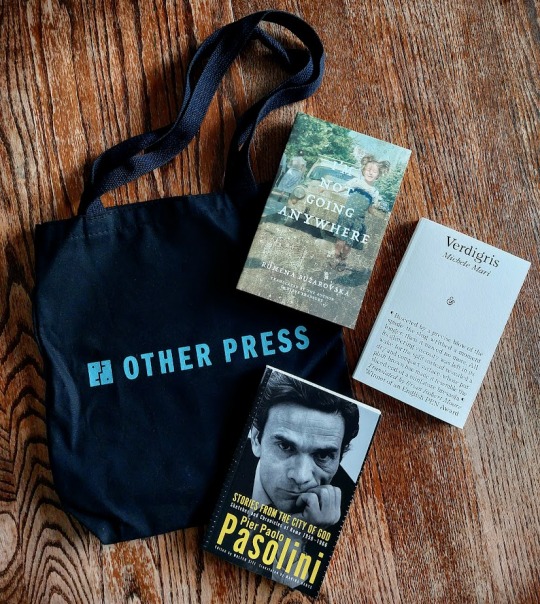

Migrations Box: Winter 2024.

I really enjoyed this subscription last year, so I'm participating again! Of the lot, I'm actually most excited for VERDIGRIS (I know, right: wild, given that cover). I love getting surprise books I'd never pick out myself hand selected and shipped directly to me.

#migrations#migrations box#subscription box#book box#stories from the city of god#pier paolo pasolini#verdigris#michele mari#i'm not going anywhere#rumena buzarovska#i really like reading translations and reading around the world and i absolutely wouldn't know where to start on my own lol#and i like the IDEA of being surprised by books but the couple SFF subscriptions i've looked at make me nervous because i already--#--preorder widely for myself (so i don't trust that i wouldn't get duplicates)#this box however is both a nice surprise and shit i absolutely have no worries about ordering myself LOL#i thought it'd come at the end of last month sooo#the fact that it came within 18 hours of mine own lil book haul was. perhaps not the greatest timing#BUT I LOVE PACKAGES AND IT FIXED MEEEE#anyway the box doesn't count toward my book buying ban things BUT#given yesterday's haul. i still should read like. 11 books. before i go out and buy more for myself lolol#this is Fine we're Fine

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the right hands, the short story form seems perfectly suited to playing out the dark side of interpersonal – especially domestic – relationships. And Rumena Bužarovska knows exactly what she’s doing. In her collection My Husband, published in English by Dalkey Press last year (and in German by Suhrkamp earlier this year), the North Macedonian author, translator and activist offers a memorable series of portraits featuring various ghastly men and the women who suffer them.

These stories are skilful, precise and occasionally darkly humorous; one from her new collection, which will be out in English in 2022 or 2023, has been published online by Electric Literature. We caught up with Bužarovska before her ILB appearance tonight (Silent Green, Sept 13, 7:30pm) to discuss her worldview, her narrative craft and her feminist activism.

Welcome to Berlin! Have you been to the ILB before?

No, I haven’t. Of course I’ve heard of the festival, so it’s a really big honour to be here. There is so much on – I feel like I’m on some kind of pilgrimage [laughs]. The program is very eclectic, and there are a ton of great writers coming. I’m especially excited after all this time with Corona, not going anywhere and not talking to anyone. A lot of people are saying we all have social anxiety now, and that’s true, but I think it goes away after like five minutes. Things are just too interesting to stay away from!

You’ll be presenting your short story collection My Husband, which centres around what men do to the women they’re in relationships with. Do you compose it as a unified project, or gather individual pieces over time?

I love short stories, and I write them often. These ones all have an underlying theme, so the book is somewhere in between a novel and a short story collection. It actually came out as a kind of explosion – the first one I wrote was “My Husband, the Poet,” which came just after I had been to a huge, overwhelming literary festival and decided to satirise it from a woman’s perspective. But then I realised a lot of the same themes were present in other stories I’d written, and I also had other relevant ideas. So I decided to give it all one frame.

The stories themselves are often satirical – but they’re also rather bleak, and the women can sometimes seem hopelessly resigned. Do you see the world bleakly, or is it just in your writing? You seem like a warm and friendly person…

Yeah, I am! [laughs] I’m very optimistic in real life. I see the world as a hopeful place, but it’s also a place full of idiots [laughs] who are just imposing their ways of living on other people, who are full or prejudice, who are putting others down for their own sake. We know how the human condition is – it’s nothing new – but I looked at it specifically in terms of patriarchy, and how things work in Macedonia. I’ve been criticised that the women in the book just accept their situations, and don’t do anything against them. But I think that’s often just the reality, especially in patriarchal societies. I like to present these conditions, realistically, because it’s a way of criticising them. And if we’re not aware of them, then we’re not able to change them.

One constant throughout the book that’s so believable – but so disturbing – is the hold that all these shitty men have over the women in their lives. But it’s all from the women’s perspectives.

What I was trying to do was to give women these voices, even though a lot of the time they’re not aware of the power they have or how they might change things. But I also wanted to allow them to speak, and allow them to be flawed. A lot of these women say things they’re not supposed to say and do things they’re not supposed to do. And they admit to it, but in a sort of hidden way, minimising the consequences of their actions – just like people do when they speak in the first person. So I wanted to give them their own voices.

The idea of the title, “My Husband”, is that this is what often gets used to identify a woman: who her husband is, what he does, whether they have children. Not being seen as someone with a personality and profession in your own right, and having to struggle against the whole history of civilisation for that. I wanted my characters to start talking about their husband, because he’s what defines them – but really they’re talking about themselves.

At yesterday’s ILB panel about the influence of Toni Morrison, one of the authors said that Morrison helped them realise it was feminist to write women that are real, even if they happen to do dreadful things, because it’s the reality that’s important.

Yes! Toni Morrison also writes with a lot of empathy. And when you make real characters – when you normalise real women – then you also empathise with them. I hoped my book could generate empathy for the characters, that people would try to understand them. We need to normalise real women, because this hasn’t been done so much in literature. And sometimes it’s unpleasant – but who cares! There’s been so much unpleasant literature about men. And we know women read more than men. So why wouldn’t we want to hear about our own perspectives on things and our own experiences? Why wouldn’t we want to become real in literature?

The ILB is international by nature – and especially the series on misogyny, which involves authors from all over the world. As someone from a smaller country, do you think what’s the value of discussing these topics at a global level?

Well, I think patriarchy is a global problem, but it has its local variants. Variants! [laughs] And literature is exactly that: we’re always talking about universal things, but what makes it specific is the social context and the local idiom. This is why we can learn so much from each other and each other’s experiences. It’s so important to think outside your box. Your brain grows a little every time you get in touch with other people who have different experiences, different languages, different cultures – and different ways of seeing things. So I’m very glad to be here. It’s been greatly missed [laughs].

You’re also involved in feminist activism, right?

Yes, I’m part a feminist group in Macedonia – we have a very strong feminist movement there actually, although it doesn’t seem to be affecting the government, which is all male and, you know, they never include women in anything. We struggle with all the major problems of patriarchy – domestic violence, economic inequality. At least now we’re aware of it; it never got talked about before. I also co-run a feminist storytelling event. And we started a sort-of #MeToo wave in Macedonia a few years ago, which really put into perspective how women were abused and harassed, especially in the workplace and universities. It did raise awareness, but in terms of systemic change, I don’t think that comes very quickly – normally it takes years or decades. But you have to start somewhere!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Ντρεπόμουν να το ομολογήσω, μερικές φορές όμως όταν ήμουν έγκυος, τη νύχτα, όταν ο Γκέντσο και ο Νένο είχαν αποκοιμηθεί, προσευχόμουν να κάνω ένα παιδί που να μην είναι σαν τον Νένο. Ένα παιδί που δεν θα έλεγε ψέματα ούτε θα έκλεβε, ένα παιδί που θα μπορούσα να το καταλάβω. Ένα παιδί αθώο, αφελές, καλό και πράο σαν αρνάκι...”

“Με τον Γκέντσο όμως είχαμε συμφωνήσει να είναι αυτός ο κακός κι εγώ η καλή, έτσι ώστε η οικογένειά μας να έχει μια καθαρή δομή”.

“...η μισαλλοδοξία προέρχεται από το σπίτι”

“Αυτό οφείλεται στο ότι οι άντρες είναι το πνεύμα και οι γυναίκες το σώμα. Οι άντρες είναι ��ημιουργικοί, οι γυναίκες πρακτικές. Οι άντρες κοιτάζουν ψηλά, οι γυναίκες προς τα κάτω. Οι γυναίκες δεν μπορούν να είναι καλλιτέχνες, δεν το έχουν από τη φύση τους”.

“...ένας άνθρωπος που δεν θέλει να αλλάζει τα πράγματα, ένας άνθρωπος που παριστάνει ότι όλα είναι όπως πριν”.

“Θα πεθάνεις από αυτό που σε τρώει. Τα μυστικά ξέρουν να σε τρώνε από μέσα”.

(Book: Ο άντρας μου, Rumena Buzarovska, Gutenberg, 2022)

0 notes