#richard tombleson

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

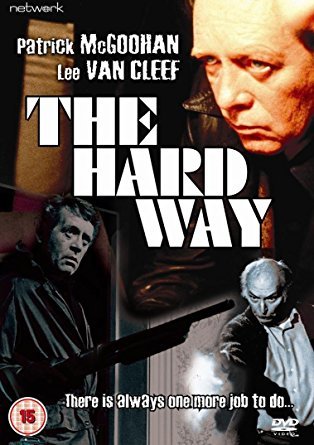

The Hard Way (1979)

“You tell him from me - this is the last.”

There isn’t a lot of information out there about The Hard Way, making it a bit of a mystery. It was produced by ITC in 1979 - that much is fact - and appears to have been intended for theatrical release. ITC had been moving steadily from TV to film production throughout the 1970s, although their films had always been licensed to other companies for release. 1979 was the year this changed, as ITC partnered with Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment (itself a conglomerate of the seperate Thorn and EMI entities, also a 1979 baby) to produce Associated Film Distribution. AFD would distribute films made by both ITC and Thorn EMI, as well as any other films the companies could pick up and sell.

AFD would be a short lived disaster, producing two of the biggest flops of 1980 before being unceremoniously wound down (prompting the retirement of ITC head honcho Lew Grade into the bargain). Those two films, incidentally, were Can’t Stop The Music (a musical-comedy faux biopic of The Village People, released just as disco was going out of style, and which inspired the Razzie awards) and Raise The Titanic (an overly long, incredibly expensive adaptation of a Clive Cussler novel that was absolutely trashed by Cussler himself). These were two hugely costly mistakes that lost millions of dollars. So why had the cheap, safe The Hard Way not made it into cinemas the year before?

I don’t have the answer, I’m afraid. Like I said, details are sparse. A little digging around, however, does hint at a troubled production. The script was written by Kevin Grogan and Richard F. Tombleson (actually Richard Ryan), with Tombleson to direct, Michael Dryhurst to produce and John Boorman to act as executive producer. How exactly a director of Boorman’s stature got involved with this minor production is also shrouded in mystery, though its worth noting that the film was made almost entirely in Ireland (where Boorman had long been based) and that the director was fresh from his own cinematic disaster (1977’s absolute mess Exorcist II: The Heretic, once described by Mark Kermode as “demonstrably the worst film ever made”). Whatever happened next, Tombleson was soon dropped as director and replaced by producer Dryhurst - anecdotal legend has it that either Tombleson found the ‘hard living’ nature of his cast too much to deal with, or that he clashed (personally or professionally) with star Patrick McGoohan.

Dryhurst had experience as an associate producer and as an assistant director, but this was to be his first project in the senior positions (his only credit as director, in fact). Whether or not ITC lost confidence in an inexperienced crew, or doubted the financial return of such a quiet, maudlin film, is pure speculation. I just don’t know (sorry, I never promised to have answers). Whatever the case, the film never got a theatrical release and instead became a TV movie and, in a few years, an early home video release. There it seems to have picked up a (very) small but devoted following.

The plot is nothing much new; McGoohan is John Connor, an aging hitman who works for hire, usually for a mercernary organization headed by McNeal (Lee Van Cleef). Connor has retired, but McNeal needs him for one last job and eventually pressures him to come out of retirement by threatening Connor’s estranged wife. Connor doesn’t go through with it, McNeal loses face and orders him killed; the scene is set for a suitably dramatic showdown. This isn’t groundbreaking, or even particularly special. But the final product is, just a little, special. Something went right, somewhere along the line, and The Hard Way turns out to be a surprisingly memorable film. I’m not saying ITC would have made a fortune, had they distributed the film to cinemas, but they certainly wouldn’t have lost millions and I’m sure it would have at least broken even…

The best word I can use to describe this film is sparse. Everything is just a little bleak, a little grey. Country landscapes are autumnal, grubby and wet. City shots seem especially grimy and gaunt. Dryhurst - who actually equips himself pretty well as a first time director - eschews closeups and keeps everyone at a middle distance, where its difficult to properly read their faces. Even the script is sparse. The whole film revolves around Connor and he’s not often offscreen for any length of time, yet he has only a handful of lines in the entire thing. Dryhurst didn’t even use an original score, instead using two ready-made pieces from Brian Eno’s 1978 experimental album, Music For Films.

The cast (Van Cleef and McGoohan aside) are mostly semi-familiar faces from British and Irish television - Donal McCann, Joe Lynch, Kevin Flood. The notable exception is Connor’s wife, Kathleen. Played by celebrated Irish novelist Edna O'Brien - in her only credited screen role - Kathleen spends most of the film isolated from the other characters. She provides much of the background and insight on Connor, delivering melancholy monologues directly to camera in what looks like a cave. Its disconcerting at first, having such a particular tone and presence for just one character (the context of her one sided conversation and its setting is not revealed until the very end of the film) but it ends up working. As the very human side of an inhumane business (Kathleen is the only truly sympathetic character in the film) she anchors everything in a state of reality and consequence. Its what prevents the film from becoming just another generic action film, or an overly grim mood Piece; the idea that though Connor is A Bad Man, and not really suited to any other life, there was a time that he was capable of love, when he was a husband and a father and not just a man with a gun.

Really though, the film belongs to the two stars - it was always going to. Van Cleef is Van Cleef; an actor who, although typecast early on as villains and murderers, was always elegant and subtle in his performances. As McNeal he is the other face of the coin to McGoohan’s Connor. Both men are getting old and getting tired, but where Connor is determined to quit, McNeal is more than ever obsessed with carrying on. His demand that Connor perform the fateful hit feels less about ‘hiring the best’ and more about preventing someone from taking the easy way out. “Men like us don’t stop”, he tells Connor when they first confront one another. In that line is his major misunderstanding of the situation, the idea that he and Connor are the same, with the same goals, drive, needs. He offers more money, but its clear from the very beginning that Connor has never been overly interested in the pay - he takes enough for himself and sends the rest to his family. “I have enough”.

McNeal is proved right in the end, in that both men find themselves unable to stop once the wheels are in motion. The final showdown - Connor entering a certain trap, McNeal rigging the house with tripwire and microphones - is a minor masterpiece of its kind. Connor is wounded early in the scene and spends the rest of it prowling around, using one arm to fire his shotgun at anything and everything that spooks him. Its a paranoid moment but you never feel like Connor has lost control - rather that he’s beyond caring, or has made peace with whatever outcome he expects.

McGoohan is incredible in these scenes, as he is throughout. As I said, he gets precious little dialogue, but it works to his advantage. Always a very physical actor, McGoohan hunches his shoulders and stalks his way slowly through the film conveying his feelings and reactions with a tilt of the head or a movement of his hand. There is a moment where Connor recieves a letter from his daughters, emigrated to America, and begins a reply. Its a simple enough scene, but as Edna O'Brien speaks in voice-over, about how he was a good father, but distant too, McGoohan holds the letter from him; he wanders to the window, stares out as if considering his reply; goes to put the letter down and apparantly move away; has second thoughts, sits and looks at the letter again; slowly, hesitantly pulls a piece of paper towards himself and picks up a pen; holds the pen as though he doesn’t know what to do next and finally, almost resigned, begins to write. Its a fantastic piece of theatre which is a lot more subtle played out than it is described here - the quiet, controlled, fastidious killer faced with the one aspect of his life which visibly makes him uncertain, which he can’t entirely control, which could be exploited as his weakness (as Kathleen is). It’s never really explained why the kids are in America, but watching the film you can’t help but feel its at least partly because Connor had no idea what to say to them.

#the hard way#patrick mcgoohan#lee van cleef#edna o'brien#donal mccann#joe lynch#kevin flood#michael dryhurst#richard tombleson#kevin grogan#itc#lew grade#raise the titanic#can't stop the music#john boorman#this is too long#mess#but yah

20 notes

·

View notes