#rabbinic magic

Text

I just went down the rabbit hole about Judaism again and I remembered one time a friend shared a post that basically went

me: I want to convert

rabbi: why tho :/

and I just interpreted that as "oh yeah they actively don't want converts so obviously you gotta convince them you're serious"

but today I found out that actually it's tradition to reject someone's request to convert three times as a test of sincerity, and I'm glad I know that now, because my socially anxious ass, upon asking a religious leader "hi can I join your community" and being told "no" would say "okay I am so sorry to bother you" and run away and jump in a hole and never be seen again like what do you mean you're expected to just keep asking until they say yes? People do that? And no one screams at them for it? They are rewarded for persistence?

anyway I'm not saying I will ever convert but it still feels like I have averted a crisis on behalf of future me today

#storyranger rambles#childhood trauma#in our house “no” was absolute and immutable and questioning the authority saying so was punished#a common refrain when I asked my mom for permission to do something and gently stressed that I needed an answer somewhat soon#was “if you need an answer now then the answer is no”#didn't matter if the permission form was due tomorrow or my friend needed an answer today otherwise my invitation was revoked#and it was my fault for not giving her enough time to decide#obviously I should have just magically gained control over deadlines set by other people#reminding her of that deadline was nagging#and if you asked her to reconsider a decision#threats were made#so yeah the idea of a ritual like this sets my teeth on edge but also I 100% agree with the rabbinical reasoning#I actually think it's great!#persistence proves dedication!#theology#I apologize to everyone who only follows me for my fanfic and my chaos media consumption#sometimes I have thoughts about other things

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

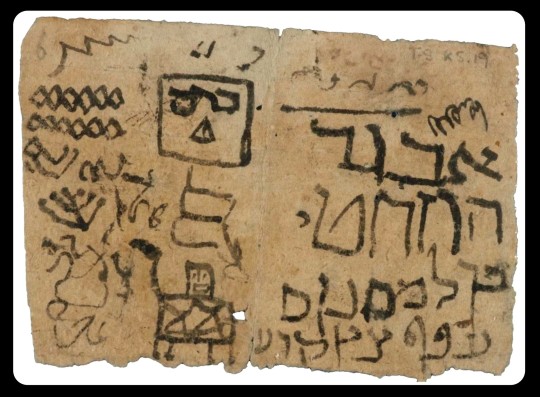

Child's Writing Exercises and Doodles, from Egypt, c. 1000-1200 CE: this was made by a child who was practicing Hebrew, creating doodles and scribbles on the page as they worked

This writing fragment is nearly 1,000 years old, and it was made by a child who lived in Egypt during the Middle Ages. Several letters of the Hebrew alphabet are written on the page, probably as part of a writing exercise, but the child apparently got a little bored/distracted, as they also left a drawing of a camel (or possibly a person), a doodle that resembles a menorah, and an assortment of other scribbles on the page.

This is the work of a Jewish child from Fustat (Old Cairo), and it was preserved in the collection known as the Cairo Genizah Manuscripts. As the University of Cambridge Library explains:

For a thousand years, the Jewish community of Fustat placed their worn-out books and other writings in a storeroom (genizah) of the Ben Ezra Synagogue ... According to rabbinic law, once a holy book can no longer be used (because it is too old, or because its text is no longer relevant) it cannot be destroyed or casually discarded: texts containing the name of God should be buried or, if burial is not possible, placed in a genizah.

At least from the early 11th century, the Jews of Fustat ... reverently placed their old texts in the Genizah. Remarkably, however, they placed not only the expected religious works, such as Bibles, prayer books and compendia of Jewish law, but also what we would regard as secular works and everyday documents: shopping lists, marriage contracts, divorce deeds, pages from Arabic fables, works of Sufi and Shi'ite philosophy, medical books, magical amulets, business letters and accounts, and hundreds of letters: examples of practically every kind of written text produced by the Jewish communities of the Near East can now be found in the Genizah Collection, and it presents an unparalleled insight into the medieval Jewish world.

Sources & More Info:

Cambridge Digital Library: Writing Exercises with Child's Drawings

Cambridge Digital Library: More About the Cairo Genizah Manuscripts

#archaeology#anthropology#history#artifact#middle ages#medieval#near east#egypt#cairo#children in archaeology#judaism#medieval jews#hebrew#writing exercise#doodle#art#cairo genizah#jewish history#reminds me of onfim#kids have always been kids

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some exciting news: the U.S. Library of Congress has digitized a collection of 230 Jewish manuscripts "from the 10th through the 20th centuries, including responsa or rabbinic decisions and commentary, poetry, Jewish magic, and folk medicine." The languages represented include Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, and Yiddish.

508 notes

·

View notes

Note

If communism happens, do you think after five dozen generations cultural and religious beliefs will just be magically unaffected and perfectly preserved as if frozen in time? 1000 years of utopia and noone's children's children's children's children will have changed their minds, hell not even changed their minds, just not adopted some beliefs to change their mind about? Do you just not think that base and superstructure interact at all?

If the Torah is to be believed, Judaism has existed for about 6,000 years. (This is 5783 by the Jewish calendar.) In those 6,000 years we went from having a temple to not having a temple to having a temple again to not having a temple again to the advent of rabbinic Judaism, and onward to present day where we have everything from Woo Reconstructionists to staunchly orthodox Haredi with every possible stop in between.

Your question betrays a deep ignorance of the topic at hand, if I'm being honest with you.

Jews have changed what it is to be Jewish as the need has arisen over the millennia. I have every confidence we will continue to do so for another 6,000 years, should humanity itself persist as long.

I'm straining to find what your ask has to do with anything I have said.

Judaism is a living culture passed from generation to generation in an unbroken chain. That fact won't change in the future, no, even as the culture itself transforms with the times. Not without outside intervention, anyway. I have 5,783 years of evidence backing me up on this.

Utopian leftists have fuck all in counterpoint but vibes.

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milton Erickson and a Rabbi Walk into a Bar... (Essay)

Finally, I've finished this essay about connections I'm finding between hypnosis, Judaism, magic, and intimacy. It's ~4.5k words, extremely "me," and I'm really thrilled to share it. Enjoy!

--

My weakness is getting deeply invested in very niche topics.

Hypnosis was my first and most lifelong obsession. It was my confusing, shameful sexual fetish that I eventually took by the horns and -- through my desire to learn as much about it as humanly possible -- turned into a job. But not a normal sex work job where I do hypnosis for money -- a weird job where I just teach about it. The kink community, and the further-specific niche where people want to hypnotize each other during intimate experiences, became my home.

But the value of study doesn't really come from the quantity of people I'm able to engage with. It comes from the way it enriches my life. It creates and benefits from the capability to see overlaps between all of my various interests.

On the surface, it may appear that two skills have no relationship. But the deeper you get into each one, a synthesis appears.

At a certain point when you are learning hypnosis, all seemingly-unrelated information seems to fit effortlessly into your hypnotic knowledge. You can listen to a song and suddenly you learn something new about how to hypnotize someone. Maybe it was a lyric that gave you an evocative emotional response; maybe it was a pattern in the music that you thought about replicating with the rhythm of your hypnotic language.

Over a decade into my own hypnosis learning, I got very lucky and found a second passionate home in communities of Jewish text study about a year ago. I started from almost zero there and found myself again to be a greedy novice, obsessed with digging into it.

Of course, as I got further, it became that I read a page of Talmud (a text of rabbinical law and conversation) and suddenly I learned something new about how to hypnotize someone. And as I progress, it is starting to go the other way: I learn about Torah study by reading about hypnosis and intimacy.

There are two directions this essay can be read. “How can intimacy and hypnosis teach us about Jewish text?” And, “How can Jewish text teach us about intimacy and hypnosis?” One half is of each part written by me as an authority, and the other half is by me as an avid novice. The synthesis of these two parts of me -- just like any synthesis between concepts -- may perhaps create something new.

Models

I’m sure most communities have a version of the idiom, “Ask three people a question and get five answers.” For a long time, this was a source of frustration for me in the hypnosis community. Is hypnosis a state of relaxation and suggestibility? Kind of, but also no. Is it more accurate to say it is based on unconscious behaviors and thoughts? Well -- kind of, but also no.

So what is it? Well, it’s probably somewhere in the overlap of about 20-30 semi-accurate definitions and frameworks for techniques -- what we’d call “models.” Good luck!

Why is hypnosis so impossible to define and teach? How have we not found a model that we can all agree upon yet? I think many people share this confusion, and it's complicated by the fact that most sources for hypnosis education teach their model as the model. It makes sense -- it would be difficult to teach a complete beginner a handful of complex frameworks with which to understand hypnosis when that person is just trying to muddle through learning “how to hypnotize someone” on a practical, basic level.

…Or would it be? By the time I got involved with Jewish study, I had long given up on chasing the white whale of some unified theory of hypnosis. I was firmly happy with the concept that all ways to describe hypnosis are simply models -- and all models are flawed, while some models are useful. I was delighted, when entering Jewish community spaces, to hear the idiom, “Three Jews, five opinions.”

This concept is baked into Jewish text study, in my experience. You can look at any single line in Torah and find innumerable pieces of commentary on it, ancient and modern, with conflicting interpretations. Torah and other texts are studied over and over -- often on a schedule -- with the idea that there is always something new to learn. And this happens partially by the synthesis of multiple people's perspectives adding to and challenging each other, developing new models. My Torah study group teacher always starts us with a famous line from Pirkei Avot, a text of ethical teachings from early rabbis: “If two sit together and share words of Torah, the Shekhinah [feminine presence of God] abides among them.”

The capacity to develop and hold multiple interpretations at once enriches your relationship with the text. So too do I believe that being able to hold multiple interpretations of what hypnosis is and how it works enhances your skill with it. It is not a failure of the system -- it is the best thing about it.

Intimacy

It is intentional to make the distinction of “relationship with the text” -- not “relationship to the text.”

My job on the surface is to teach hypnosis, but the meta goal is to simply teach something that helps people develop profound intimacy with others. I think that hypnosis is a kind of beautiful magic that is well-suited to this, but it’s not the only path to take.

One of my favorite educators, Georg Barkas, describes themselves as an intimacy educator who teaches rope bondage. Their classes and writings are highly philosophical and align closely with my own ideas about intimacy -- as well as my partner’s, MrDream, from whom I’ve learned so much. I frequently cite Barkas when I talk about hypnosis because I feel the underlying ideas they have about rope bondage are extremely applicable to all kink and intimacy -- and I will continue that trend here.

Barkas recently published an excellent essay looking in detail at the concept of intimacy itself. They posit that our first thought of intimacy is usually about a kind of comfort-seeking and familiarity. That’s contained within the etymology of the word, and socially it’s what many of us think of when we define our relationships as “intimate”: settling in to engage with a partner who we love, know, and understand.

But, Barkas asks, what if we place this word into a different context? They talk of how in scientific endeavors, the goal of “becoming familiar with” is unpredictability and discovering things that are surprising and unexpected. This perhaps offers a different view of intimacy: intimacy where you do not engage with your partner as though you know everything about them; intimacy where being surprised by them and learning something new is the goal.

My partner MrDream teaches about this often in hypnosis education: approaching a partner with genuine curiosity and interest -- “curiosity” implying that you don’t know what to expect, with a positive connotation. There is a kind of delicate balance between being able to anticipate some aspects of what is going to happen hypnotically -- to have a general grasp on psychology and hypnosis theory -- versus holding tight to a philosophy that neither you nor the hypnotic subject really knows how they are going to respond. The unexpected is not to be feared, but celebrated and held as core to our practice. Hypnotic “subjects” (those being hypnotized) who can relax their expectations will often have more intense experiences.

Thus we come to the first time in this essay where I mention Milton Erickson, my favorite forefather of modern hypnosis. Erickson was a hypnotherapist active through the 1900s and is famous (among many things) for presenting a model of hypnosis that wasn’t necessarily an authoritative action done to a person, but a collaborative and guiding action done with a person.

In his book “Hypnotic Realities,” he talks about how his view of clinical hypnosis is defined by how the therapist is able to observe each individual client and directly use those observations to continually develop a unique hypnotic approach with them. The client’s history, interests, and modes of thinking are utilized for the trance, as well as any observable responses they have in the moment. For example, a client with chronic pain may have the frustration they express over that pain incorporated into the trance. This is in deep contrast to hypnosis where the therapist comes in with any kind of “script” or formula to recite ahead of time.

It’s important to Erickson’s model that the therapist doesn’t know exactly what to anticipate, and it’s also important hypnotically that the same is true for the client. A common “Ericksonian” suggestion is, “You don’t have to know what is going to happen, and I don’t know either.” In order to develop the most effective approach with each patient, Erickson would enter into a session with some presumed knowledge, but ultimately learning -- not assuming -- how to best hypnotize each individual person.

We circle back to the phrase, “a relationship with Jewish text.” In my opinion, engaging with Torah is exactly this kind of intimacy. Torah is something we come into in order to poke and prod at it, to interact with it and to see how it interacts back at us. The teacher of my study group always cites a model where Torah itself is a participant in our partnered learning and group discussions. We ask it questions, we push its boundaries, we strive to glean something new and yet unseen. A line that may seem simple on the surface can reveal much more when we explore its context or put it into a different context entirely.

This is easier for me to say as someone who is coming into learning Torah for the first time, but I am able to look ahead to when I will be fully familiar with the text and still be able to take this expanded definition of intimacy with it. Not coming to it without a sense of comfort, but still engaging with curiosity. MrDream teaches a model for hypnosis that is based on the idea of exploration -- exploring your partner no matter how long you have been with them. You are always coming to them as a different person, shaped by your ever-growing experiences and identity, and your partner changes as a human as well. I believe Torah is also dynamic in this way, as the context within which it exists -- and the way we interpret it -- is constantly shifting.

Ritual

I have been engaging with spiritual ritual on and off for as long as I’ve been learning hypnosis. The concept of magic has always been alluring to me -- not from a motivation to meet specific goals, but for something more difficult to pin down. I like that ritual, in an esoteric framework, is about looking at various metaphors between ingredients and actions; a candle representing an element of fire which may in turn represent intensity, or purity, or something else. Drawing meaningful connections between concepts like this is a skill I’ve developed in parallel with hypnosis, as well.

I was recently talking with a friend of mine who is also interested in esotericism -- we were sharing our frustrations with various books on magic and ritual. We wondered why so many sources would go on to teach prescriptivist formulas and associations, and not much else. Do this, and that will happen. This symbol represents that. My friend and I agreed that the ritual value of ingredients comes from how you personally assign meaning to them -- but why was everything always trying to teach us their meaning, as opposed to teaching us how to cultivate our own associations?

A week or so later, I happened to go to an excellent class that explored whether or not there was a place for smudging and smoke use in modern Jewish ritual. The teacher first took a careful, measured approach towards looking at indigenous smudging practices and the concept of appropriation. What followed was 30 minutes of history and text exploring examples of smoke in early Judaism, and then 30 minutes of a handful of interpretations of what “smoke” could mean and represent with relation to Jewish ideas -- directly practical to modern ritual. It was utterly excellent and immediately profound for me, as someone who has been yearning to blend my experience with esoteric ritual with my relationship with Judaism.

Observant readers will note that through this essay I speak passively about Judaism -- I am a patrilineal Jew, which for better or worse means that it is not a simple matter to say, “I am ‘fully’ (or ‘not’) Jewish.” (I am in the beginnings of working with a Conservative rabbi -- who affirms that I’m Jewish -- to make my status halachic [lawful], which is deeply exciting.) Opinions on that aside, a relevant piece of information is that the Jewish holiday we celebrated most consistently when I was growing up was Chanukah. While a lot of Jewish practice has been something I’ve been striving towards as an adult, Chanukah has always been “mine.” It was fast approaching after this class, and I felt motivated to use my newfound knowledge to make more ritual out of lighting the candles.

I was deeply surprised when all I did was light a stick of incense before saying the blessings over lighting the menorah, and my experience transformed into something intense. I smelled the incense and couldn’t help but think about what I’d learned about the Rambam’s commentary that incense in the time of the Temple was about making the Temple smell sweet to pray in after the burning of sacrifices. I thought about what I’d learned about the presence of God being smoke and clouds to the ancient Israelites. I thought about things I’d learned from other places -- hiddur mitzvah (the value of beautifying a practice), and a midrash (parable) about God loving the light and rituals we do in a very personal way simply because they are from us.

Esoteric ritual has often felt to me like exerting effort in making the associations of ingredients work for me. But this was effortless. I was doing something that was entirely my own, solidly founded by the broad and deep study I’d done, by my personal relationship with the concepts, by my identity.

In other words, the power behind this ritual came from knowledge, and the knowledge came from my intimacy with it. And that intimacy was not just with the study I had done -- it was also the process of being surprised in real time by what I was learning through the ritual itself.

Hypnosis gains “power,” in so much as we let ourselves use the term, through these same acts of intimacy towards knowledge. It operates directly based on various ingredients: how much we know about hypnosis theory itself, general psychology, the person we are working with, and ourselves. Hypnosis is a ritual -- it is setting aside special time to do something with a collection of ingredients that you have personal associated meanings with. If you can’t connect to those deeply enough, it won’t reach its full potency.

Knowledge, Perception, and Unconsciousness

One of my favorite concepts to teach in hypnosis is, “A change in perception equates to a change in reality.” This is derived from Erickson by MrDream, and it’s something he and I have had a lot of conversations about to refine. The implication of this is not something as trite as hypnosis having the power to change a person’s perceived reality. It is the concept that if you look at something from a different perspective, you gain various different capabilities.

For example, when you are feeling stuck in a situation and you think about what a close friend of yours would do if they were in your shoes, you gain the capability to see more options, to change your actual view of the reality of the problem and therefore change your actions towards it. In hypnosis, this could be the difference between simply telling someone to relax their legs versus another perspective of telling them to imagine what it would be like if their legs just started relaxing. It could be the idea that when a person does feel relaxation from a simple suggestion, their perception changes on what is happening -- they build more belief in hypnosis, and that belief in turn makes the next suggestions easier to buy into.

Erickson’s model of hypnosis is predicated on the idea that hypnosis itself matters, that hypnosis is a time within which someone’s reality changes. In his ideal hypnotic context, the subject feels like they no longer can expect things to behave as they usually do in their “waking” reality. They are thus opened to many different kinds of new experiences and capabilities. To Erickson, perception matters -- by itself, it’s a primary driving force behind literal change and response.

This ties back to our idea of intimacy -- just as I aim to approach my partners with this profound curiosity, just as I aim to approach Torah, I want to have this intimacy of the unexpected with trance itself. I want to allow myself to be surprised by hypnosis, by the things I don’t yet know about it even after more than a decade and thousands of hours of trance. But more than this, in an Ericksonian sense, simply changing my perspective to this motivation is one of the things that lets me get there.

I went through a guided study class about Shabbat (Judaism’s weekly sabbath of rest) with a partner, and so much of the class was in the abstract that it at times felt difficult for me to latch onto. We were learning all of this background context about a view of Shabbat where instead of spiritually striving and reaching on that day, you come in acting as though your spiritual work -- like your other work -- is “finished.”

In one session, we spent a chunk of time parsing through how we could interpret that as actionable. It felt like it just wasn’t clicking for me -- the midrashic texts weren’t offering enough for me to feel like I could make judgments on questions like, “Does this imply I shouldn’t meditate on Shabbat in this context?”

It wasn’t until I slept on it that I found a very simple piece of the puzzle: putting aside the questions of concrete actions, in an Ericksonian sense, the internal act of shifting my perspective would absolutely change the way I behaved and interacted with the day. It would become more indirect and unconscious -- instead of carefully analyzing my actions as I might with other Shabbat prohibitions on work, I could simply let myself act in ways that fit that perspective of “spiritually resting.”

The abstraction of the class made more sense -- perhaps it wasn’t trying to give us direct answers, but rather create a psychological environment for us that was well-suited to this more unconscious processing. Or rather, in addition to the sort of typical conscious halachic interpretation. If I allow myself an opinion here, I’d say that I care about halacha as actionable, but as always, I tend to care more about feelings and what’s internal.

This also lent credence to ways this class and the class on smoke and ritual changed my experiences. I was not given a set of actions to take, but rather a variety of perspectives that unconsciously made me think and behave differently. The concept of “knowledge is power” is both true and alluring in many different contexts, and yet had often fallen through for me in most ritualistic frameworks. The way that it succeeds, I believe, is when you develop a relationship with knowledge that actually changes your internal perspective and perceptions.

Limitation

With this we return to the concept of models and interpretations. It is serendipitous to be going through these experiences at a time where I am avidly working on my next book -- the thesis of which is that in order for us to progress as hypnotists, we must get comfortable moving fluidly between many differing definitions and frameworks (models) of what hypnosis is and how it works.

It is as the Ericksonian principle would say: If you take a perspective on hypnosis that boils down to “hypnosis is about relaxing the conscious mind,” you will do hypnosis according to that perspective. You will use relaxation-based techniques and make an effort to get someone to think “less consciously.” If you instead take a perspective that is “hypnosis operates based on activation of the conscious mind,” you may do hypnosis that causes someone to think and process in a more stimulating way.

Both and neither are true, and they can coexist. I believe that most models can be useful -- some more useful than others. But the best thing you can do is to not assume that one model is the most correct one -- instead, it is to develop the capacity to work within many at once even while being aware of their boundaries.

Jewish text, in my experience, provides models -- perspectives that themselves give guidance on how to understand things and act. I think especially about midrash and stories that are explicitly intended to fill in the gaps or give an alternate view on something. The question of, “Is there one correct way to do/see things” is more complicated here, but there are areas -- especially in those subtle shifts of mindset for ritual or interpreting text -- where the answer is still “no.”

My time so far in Jewish study supports this in a different way. There is a human element of collaboration and challenge. Learning as we do with a chevruta (study partner) adds another person to the relationship -- it is no longer just between you and the text. There is another human who you are building something with, and it is “intimate” according to our exploratory definition in an even clearer way.

The purpose of a “scene” inside of kink (a “session” of kink play) is to operate in a semi-limited framework -- limitations exist on who is involved, where it begins and ends, how partners communicate, and what themes/topics/activities are involved. These limitations -- though they may be quite broad -- are partially what allow for intense experiences. A scene needs to exist in a different “space” than our daily lives, and it needs to operate by different rules and involve different ingredients. Here, we also see overlaps with the definition of a “ritual.”

This doesn’t just facilitate intensity (and safety) -- it facilitates learning something new about your partner. By taking your relationship and putting it into a limited context, it allows you to observe it in a more careful way, where novel changes can be more obvious.

Studying with a chevruta is much like this. I have had study sessions where my chevruta and I are meeting for the first time and the only thing we are aware of sharing is our desire to dive into a piece of text. I’ve also had chevrutas where we know each other outside of study, and some of our time is schmoozing and catching up. But in all cases, we are limited in scope, and that limitation creates ease of access towards the common goal of expanding our knowledge and relationship with the text. We are focused; we are motivated. We are creating something that we can only create through who we are as individuals and what we are doing as avid learners.

This has surprised me at times with its tenderness and intensity. Building well-founded interpretations with someone is in and of itself very intimate -- not sensually, but humanly. It has given me something I have always wanted -- an intimacy that is pervasive not just in application of knowledge, but in the development of it. A feeling of sacredness and joy from being able to see so many different perspectives.

I long for this connection, this alchemy. Yes, all models are limited. But within those tight, restricting limits is the potential energy of creation.

“And I Must Learn”

There is an infamous story in the Talmud, in Berakhot 62a, where Rav Kahana hides under the bed of his friend Rav Abba. Rav Kahana hears Abba and his wife giggling and starting to have sex, and remarks out loud that Rav Abba is acting like someone who is famished. Rav Abba, mid-sex, understandably says, “Kahana, why the fuck are you under my bed listening to me fuck my wife?” Rav Kahana replies, “It is Torah, and I must learn.”

There was a version of this essay that began with this tale. I am enamored with the vast overlaps I can derive from its briefness: that intimacy can be studied sacredly both as a general concept and specifically with your partner; that we are obligated to learn ourselves, our partners, and general human desire; that there can be a thread of wholeness in every action of your life if you give every action sacred attention.

Even this, though, is a limited-context interpretation. The rabbis of the Talmud were certainly not sex-positive, especially not as we currently use the term. The surrounding triptych of conversations is similarly humorous but seems to comparatively describe sex as dirty or gross, and this bit of text cannot really exist separately from all of the places where there is halacha derived about sex that is about controlling women’s bodies or preventing queer and trans people from being able to live authentically.

But -- we are allowed to interpret like this. We are allowed to play with context and see what we discover.

For me, this is about finding the connections between my actions and my interests; parts of me that synthesize the whole. It is about developing intimacy with Torah, with my learning partners, with my romantic partners; with the people within the writings, with the authors, and with the readers.

Reading Torah is the same as hypnotizing someone is the same being intimate with someone is the same as doing a ritual. All things on a broad enough scale overlap this closely. There is value in this “zooming out” to a wide enough context to see the connections that exist -- just as there is value in celebrating the limitations that arise, models nestled alongside each other, when you “zoom in.”

We need both to be able to treat our learning -- all forms of it -- as something special.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tree of Life

Talon Abraxas

The Sacred Tree of the Sephiroth.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life

The tree of life (Hebrew: עֵץ חַיִּים) is a diagram used in Rabbinical Judaism in kabbalah and other mystical traditions derived from it. It is usually referred to as the "kabbalistic tree of life" to distinguish it from the tree of life that appears alongside the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the Genesis creation narrative and well as the archetypal tree of life found in many cultures.

The tree of life usually consists of 10 or 11 nodes symbolizing different archetypes and 22 paths connecting the nodes. The nodes are often arranged into three columns to represent that they belong to a common category.

In kabbalah, the nodes are called sefirot. They are usually represented as spheres and the paths (Hebrew: צִנּוֹר, ṣinnoroṯ) are usually represented as lines. The nodes usually represent encompassing aspects of existence, God, or the human psyche. The paths usually represent the relationship between the concepts ascribed to the spheres or a symbolic description of the requirements to go from one sphere to another. The columns are usually symbolized as pillars. These usually represent different kinds of moral values, electric charges, or types of ceremonial magic.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sacred Tree of the Sephiroth.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life

The tree of life (Hebrew: עֵץ חַיִּים) is a diagram used in Rabbinical Judaism in kabbalah and other mystical traditions derived from it. It is usually referred to as the "kabbalistic tree of life" to distinguish it from the tree of life that appears alongside the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the Genesis creation narrative and well as the archetypal tree of life found in many cultures.

The tree of life usually consists of 10 or 11 nodes symbolizing different archetypes and 22 paths connecting the nodes. The nodes are often arranged into three columns to represent that they belong to a common category.

In kabbalah, the nodes are called sefirot. They are usually represented as spheres and the paths (Hebrew: צִנּוֹר, ṣinnoroṯ) are usually represented as lines. The nodes usually represent encompassing aspects of existence, God, or the human psyche. The paths usually represent the relationship between the concepts ascribed to the spheres or a symbolic description of the requirements to go from one sphere to another. The columns are usually symbolized as pillars. These usually represent different kinds of moral values, electric charges, or types of ceremonial magic.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because of the semi-recent uproar stirred by by J/K/R's blatant antisemitism in that new H/ar/ry P/ott/er game (putting slashes to keep this post from potentially showing up in searches for those terms bc theyre not the focus of this post), and the drive to make the Wizard101 community more explicitly Jewish-friendly, there is a word floating around in wizard101 canon and thus in the wizard101 communities online that I'd like to call attention to.

Cabal

The name of the major antagonists in the second half of Arc 3 and beyond. Host to some of our favorite characters.

The word 'cabal' simply means "a secret political clique of faction".

Why am I calling attention to this word and name?

The word cabal is derived from the rabbinical Hebrew word 'Kabbalah', the word for Jewish religious teachings (specifically study and interpretation of the Torah). I hope I don't have to explain why turning the word for our religious studies into meaning a secret political organization is antisemitic as fuck.

Im not blaming the wiz communities online for using this word, and Im not sure I can even blame the writers for not considering the antisemitic roots of the word. The writers likely didnt think 'oh, let's intentionally use an antisemitic word for the villains we want to introduce'. Antisemitism is woven into our language and culture. Cabal was an antisemitic word and concept before it was a name for a group of fictional villains in an MMORPG.

That being said, we don't have to be (and in fact, we SHOULDN'T be) complacent in antisemitism. Language matters. Therefore, if I may, I'd like to suggest a word we can use instead of Cabal/Cabalists:

Schismist

In canon, the Cabal and Arcanum had been one entity (the old Arkanum) before the Great Schism happened in which the two broke apart into what they are today. The Cabalists were the ones forced out, and the ancestors of the modern Arcanum followed the goal of studying all the schools of magic, rather than studying how to survive the apocalypse.

A friend offered this word up to a discord server we were in, and we all made the switch there.

I'm not asking for much. Just for us to be the slightest bit conscious of our language. Just for us to replace one word for another.

#wizard101#w101#wizard101 fandom#w101 fandom#wizzy#wizzy fandom#sorry for spamming tags. this is important to me.

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

The mezuzah was also an object of suspicion, and at the same time desire. That it was regarded as a magical device by Christians we know, for a fifteenth-century writer admonished his readers to affix a mezuzah to their doors even when they occupied a house owned by a non-Jew, despite the fact that the landlord might accuse them of sorcery. Indeed, the Jews in the Rhineland had to cover over their mezuzot, for, as a thirteenth-century writer complained, “the Christians, out of malice and to annoy us, stick knives into the mezuzah openings and cut up the parchment,” Out of malice, no doubt—but the magical repute of the mezuzah must have lent special force to their vindictiveness. Yet even Christians in high places were not averse to using these magical instruments themselves. Toward the end of the fourteenth century the Bishop of Salzburg asked a Jew to give him a mezuzah to attach to the gate of his castle, but the rabbinic authority to whom this Jew turned for advice refused to countenance so outrageous a prostitution of a distinctively religious symbol.

Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion; The Legend of Jewish Sorcery

#joshua trachtenberg#jewish magic and superstition: a study in folk religion#jewish magic and superstition#the legend of jewish sorcery#antisemitism#mezuzah#mezuzot

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

Three queens of Hell are called Lilith sisters.

Naamah, Eisheth Zenunim and Mahlat bat Agrat were created to be Adam's wives.

Adam didn't accepted Naamah since after seeing how she was created he stated he couldn't love her.

Sometimes Naamah, Eisheth Zenunim and Mahlat bat Agrat were created along side Eve as a back up plan if Adam didn't like Eve.

"In the rabbinic literature of Yalquṭ Ḥadash, on the eves of Wednesday and Saturday, she is "the dancing roof-demon" who haunts the air with her chariot and her train of 18 messengers/angels of spiritual destruction. She dances while her mother, or possibly grandmother, Lilith howls.[1]

She is also "the mistress of the sorceresses" who communicated magic secrets to Amemar, a Jewish sage.[1]

In Zoharistic Kabbalah, she is a queen of the demons and an angel of sacred prostitution, who mates with archangel Samael along with Lilith and Naamah,[1] sometimes adding Eisheth as a fourth mate.[2][3]

According to legend, Agrat and Lilith visited King Solomon disguised as prostitutes. The spirits Solomon communicated with Agrat were all placed inside of a genie lamp-like vessel and set inside of a cave on the cliffs of the Dead Sea. Later, after the spirits were cast into the lamp, Agrat bat Mahlat and her lamp were discovered by King David. Agrat then mated with him a night and bore him a demonic son, Asmodeus, who is identified with Hadad the Edomite.[4]

Mahlat and Agrat are proper names, "bat" meaning "daughter of" (in Hebrew). Therefore, Agrat bat Mahlat means "Agrat, daughter of Mahlat.""-wikipedia about Mahlat bat agrat

"Naamah or Nahemoth (Hebrew: נַעֲמָה; "pleasant") is a demon described in the Zohar, a foundational work of Jewish mysticism. She originated from and is often conflated with another Naamah, sister to Tubal-cain.

In Talmudic-midrashic literature, Naamah is indistinguishable from the human Naamah, who earned her name by seducing men through her play of cymbals. She also enticed the angel Shamdon or Shomron and bore Ashmodai, the king of devils. It was later, in Kabbalistic literature like the Zohar, that she became an inhuman spirit.[1]

A 1340 Kabbalistic treatise by Bahya ben Asher states Naamah is one of the mates of the archangel Samael, along with Lilith, Agrat bat Mahlat and Eisheth.[5][6][7] It is stated Esau took four wives in imitation to him.[1]

According to the Zohar, after Cain kills Abel, Adam separates from Eve for 130 years. During this time, Lilith and Naamah seduce him and bear his demonic children, who become the Plagues of Mankind. She and Lilith cause epilepsy in children.[2]

In another story from the Zohar, Naamah and Lilith are said to have corrupted the angels Ouza and Azazel.[3][4] The text states she also attracts demons, as she is continuously chased by demon kings Afrira and Qastimon every night, but she leaps away every time and takes multiple forms to entice men."-wikipedia about Naamah.

"In Kabbalah, Eisheth Zenunim (Heb. אֵשֶׁת זְנוּנִים, "Woman of Whoredom") is a princess of the qlippoth who rules Gamaliel, the order of the qlippoth of Yesod.[1] She is found in Zohar 1:5a as a feminine personification of sin.[2] In Jewish mythology, she is said to eat the souls of the damned.[citation needed]"-wikipedia about Eisheth Zenunim.

About qlippoth (source wikipedia):

"In the Zohar, Lurianic Kabbalah, and Hermetic Qabalah, the qlippoth (Hebrew: קְלִיפּוֹת, romanized: qəlippoṯ, originally Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: קְלִיפִּין, romanized: qəlippin, plural of קְלִפָּה qəlippā; literally "peels", "shells", or "husks"), are the representation of evil or impure spiritual forces in Jewish mysticism, the opposites of the Sefirot.[1][2] The realm of evil is called Sitra Achra (Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: סִטְרָא אַחְרָא, romanized: siṭrā ʾaḥrā, lit. 'The Other Side') in Kabbalistic texts.

The qlippoth are first mentioned in the Zohar, where they are described as being created by God to function as a nutshell for holiness.[3] The text subsequently relays an esoteric interpretation of the text of Genesis creation narrative in Genesis 1:14, which describes God creating the moon and sun to act as "luminaries" in the sky. The verse "Let there be luminaries (מְאֹרֹת)," uses a defective spelling of the Hebrew word for "luminaries", resulting in a written form identical to the Hebrew word for "curses". In the context of the Zohar, interpreting the verse as calling the moon and sun "curses" is given mystic significance, personified by a description of the moon descending into the realm of Beri'ah, where it began to belittle itself and dim its own light, both physically and spiritually. The resulting darkness gave birth to the qlippoth.[4] Reflecting this, they are thenceforth generally synonymous with "darkness" itself.[5][6]

Later, the Zohar gives specific names to some of the qlippot, relaying them as counterparts to certain sephirot: Mashchith (Hebrew: מַשְׁחִית, romanized: mašḥīṯ, lit. 'destroyer') to Chesed, Af (Hebrew: אַף, romanized: ʾap̄, lit. 'anger') to Gevurah, and Hema (Hebrew: חֵמָה, romanized: ḥēmā, lit. 'wrath') to Tiferet.[7] It also names Avon (Hebrew: עָוֹן, romanized: ʿāvōn, lit. 'iniquity'),[8] Tohu (Hebrew: תֹהוּ, romanized: tōhū, lit. 'formless'), Bohu (Hebrew: בֹהוּ, romanized: bōhū, lit. 'void'), Esh (Hebrew: אֵשׁ, romanized: ʿēš, lit. 'fire'), and Tehom (Hebrew: תְּהוֹם, romanized: təhōm, lit. 'deep'),[9] but does not relate them to any corresponding sefira. Though the Zohar clarifies that each of the sefirot and qlippoth are 1:1, even down to having equivalent partzufim, it does not give all of their names."

About Yesod:

"Yesod (Hebrew: יְסוֹד Yəsōḏ, Tiberian: Yăsōḏ, "foundation")[1][2] is a sephirah or node in the kabbalistic Tree of Life, a system of Jewish philosophy.[3] Yesod, located near the base of the Tree, is the sephirah below Hod and Netzach, and above Malkuth (the kingdom). It is seen as a vehicle allowing movement from one thing or condition to another (the power of connection).[4] Yesod, Kabbalah, and the Tree of Life are Jewish concepts adopted by various philosophical systems including Christianity, New Age Eastern-based mysticism, and Western esoteric practices.[5

According to Jewish Kabbalah, Yesod is the foundation upon which God has built the world. It also serves as a transmitter between the sephirot above, and the reality below. The light of the upper sephirot gather in Yesod and are channelled to Malkuth below. In this manner, Yesod is associated with the sexual organs. The masculine Yesod collects the vital forces of the sephirot above, and transmits these creative and vital energies into the feminine Malkuth below. Yesod channels, Malkuth receives. In turn, it is through Malkuth that the earth is able to interact with the divinity.[6]

Yesod plays the role of collecting and balancing the different and opposing energies of Hod and Netzach, and also from Tiferet above it, storing and distributing it throughout the world. It is likened to the 'engine-room' of creation. The Cherubim is the angelic choir connected to Yesod, headed by the Archangel Gabriel. In contrast, the demonic order in the qlippothic sphere opposite of Yesod is Gamaliel, ruled by the Archdemon Lilith.

In Western esotericism, according to the writer Dion Fortune, Yesod is considered to be "of supreme importance to the practical occultist...the Treasure House of Images, the sphere of Maya, Illusion."[7]"

Whoo this was a read! Hebrew mysticism/myths is quite fascinating

Ppl do hebrew myths a big dusservice w/ only focusing on a surface level with lilith

#text.post#text.#hazbin hotel critical#hazbin hotel criticism#vivziepop critical#hazbin hotel critique#ask#ask me stuff#my asks#my ask#hebrew mythology#religious figures

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

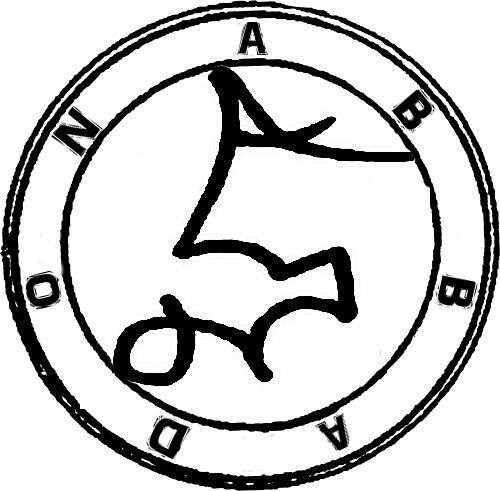

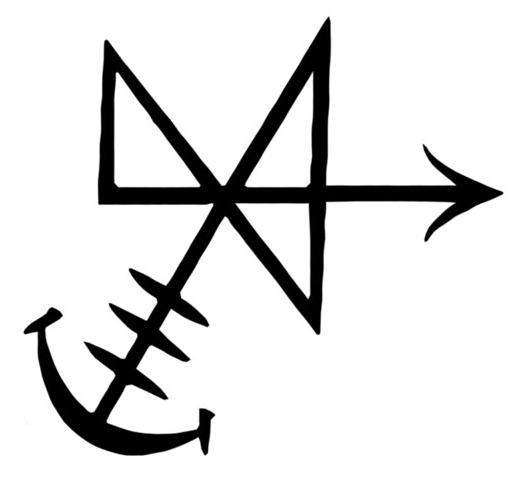

ABADDON(APOLLYON)

Enn:Es na ayer Abaddon avage

Other names:Appolyon, Apollyon, Appolion, Abbadan, Abbaton, Abadon

Originally, Abaddon was a place and not an angel or being. In rabbinic writings and the Old Testament, Abaddon is primarily a place of destruction and a name for one of the regions of Gehenna (see Hell). The term occurs six times in the Old Testament. In Proverbs 15:11 and 27:20, it is named with Sheol as a region of the underworld. In Psalm 88:11, Abaddon is associated with the grave and the underworld.

Abaddon (Apollyon) is the angel of death, destruction, and the netherworld. The name Abaddon is derived from the Hebrew term for “to destroy” and means “place of destruction.” Apollyon is the Greek name.

In magic Abaddon is often equated with Satan and Samael. His name is evoked in conjuring spells for malicious deeds. Abaddon is the prince who rules the seventh hierarchy of demons, the Erinyes, or Furies, who govern powers of, discord, war, and devastation.

In Job 26:6, Abaddon is associated with Sheol. Later, Job 28:22 names Abaddon and Death together, implying personified beings. In Revelation 9:10, Abaddon is personified as the king of the abyss, the bottomless pit of hell. Revelation also cites the Greek version of the name, Apollyon, probably a reference to Apollo, Greek god of pestilence and destruction.

Abaddon destroys false illusions and masks, however once the truth is revealed the foundation of truth is planted. He transforms the energy and core power can rise from the depth of our soul. Abaddon reveals the practitioners core power just as he crushes and destroys. The practitioners courage comes out a destroys the illusions. He is a powerful guide and imitates the journey through the depth of darkness. The journey of the abyss is one of countless trials and lessons. Abaddon is one is an incredible teacher and Advisor and reveals the truth of the dark depth within.

Call upon Abaddon for

⬩Courage

⬩Destroy false illusions

⬩Destroy masks

⬩Transformation

⬩Truth within even ones we don't wish to hear

⬩Ask him what else he will work with you on⬩

⊱•━━━━━━⊰In Ritual⊱━━━━━•⊰

Enn:Es na ayer Abaddon avage

Sigil:Posted above

Plant:Chamomile, Calendula, Aloe, Elder, Tillandsia Xerographica, African Blackwood, Walnut, Eucalyptus

Incense:Black Copal, Benzoin, Dragons Blood, Labdanum, Opoponax

⬩Red, black, purple, metallic grey, silver candles or objects

⬩Ask Abaddon what he likes⬩

⬩It is important to learn protections before trying to work with any spirits. You can get tricksters and parasites if you don't.

Cleansings- cleaning your space of negative energies. You can burn herbs or incense for this.

Banishings- forcing negative energies out of your space. The lesser banishing ritual is one of the most commonly used.

Warding- wards keep negative energy out of your space. Amulets, sigils and talismans do this.

Set up a your space and do a cleanse and banishing. Have wards up in your home. Meditation is to calm yourself and get your mind ready. The sigil (symbol) is what you draw on paper. The enn is what you chant or say to call forth the spirit.⬩

#demonology#occult#demonolatry#demons#daemons#witchcraft#deity#witchblr#Dukante#dukante#Dukante hierarchy#Abaddon#Appolyon#Apollion#Abbadan#Apollyon#Abbaton#Abadon#occultblr#paganblr

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

From The Torah Studio:

"The Book of Worlds To Come is a completely new tabletop roleplaying game (TTRPG) being designed by our Director of Online Learning, Lexi Kohanski . Play a group of mystical spell-casters wandering Roman-occupied Judea/Palestine. Speak to angels in actual Biblical/Rabbinic Hebrew. Discover a magical world full of people, demons, angels, and spirits inspired by the history of the post-Destruction Holy Land - and make that world into the World To Come.

This year we’re beta-testing this TTRPG at the Torah Studio. That means the game isn’t finished yet, and it’ll continue to grow as you play. You get to be among the first people to play the game. Go where literally no one has gone before!

This summer we’re running groups of 6 lucky beginners each! We’ll learn the Hebrew alphabet, gain some core vocab, and learn how to write sentences in the present and past tense. If those sound like skills you want to acquire by roleplaying, sign up for the campaign on our site!

If you’re not a beginner, fret not! We’ll be offering more campaigns throughout the year. If you’d want to play but you’re at a different Hebrew level, DM us so we can tally up interest at various levels and offer you the perfect RPG/Hebrew experience!

Sessions will run in July, August, and Sept, with groups on Sundays and Tuesdays. Each session builds on the last one, so unlike other Torah Studio offerings you’ve gotta commit one month at a time. The cost for one campaign, the equivalent of an introductory Hebrew course plus the fun of playing an RPG, is $120. See our site for more info on pricing." [site linked above]

Highly recommend this teacher!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this week’s parsha, Moses is told by Hashem that he will not see the promised land, but his descendants will. Like Moses, we know that a healed world will not come in our lifetime. We hope for it, we pray for it, we work our asses off for it, we dedicate ourselves to a practice of expecting it — but realistically we know that our work is to water the seeds of healing for our descendants to bloom, not for ourselves.

And the thing that we are doing when we work and pray for a joyful future, another word for that is magic. When we do the practices that connect us with our ancestors — our ancestors even further back than the rabbinic traditions, the Jewish wise women and healers and herb workers and amulet makers and mystics who were drawing on the divine creative power to shape the world to their touch — when we dance the same dances they knew, when we raise our voices in the same songs and prayers and wordless niggunim that they did, when we play with and against the fractal harmonies of Hashem moving around and through and inside us — that is magic.

And throughout history, we have seen systems of domination be deeply invested in crushing these kinds of magic, and we have seen these buds of disobedient mysticism and witchcraft bursting their way back through the asphalt over and over again.

The reason they want to eradicate us is the same reason that we cannot be eradicated: that magic belongs to the earth and the people and the body and it cannot be controlled. When we find pockets of disobedience in ourselves, we find both the key to our power and the key to the danger we’re in.

It’s not a coincidence that the people who want me dead because I’m trans and the people who want me dead because I’m jewish are the same people doing the same stuff for the same reasons. The foundation of the magic that we do is to democratize the realm of the spirit, take it away from the domain of hierarchy, and hierarchy’s response to this is to fight back with all its considerable power.

My family is being hunted and if you think of me as your sibling it’s your family too. This is not about how I need you to do something on my behalf. This is about you finding a spark of disobedience in your own heart. It might be a strong flame! Or it might feel like a sputtering ember. But what you need to do right now is blow on that spark and feed it and keep it safe, because that spark is the thing that binds all of us together — Jews, and Muslims, and queers, and refugees, and midwives, and gender refuseniks, and perverts, and revolutionaries, and sex workers, and witches, and descendants of the Bund and the Black Panthers, and the Priestesses — all of us disobedient ones. That collective fire is the source of our power and it’s what we connect to when we do magic.

And it’s time for your magic now. if you see the fact that we won’t reach the promised land in our lifetimes and use it as an excuse to give up, it’s a victory for those that want to crush your magic. The hour is late and the world needs you — Hashem needs you — and I personally need you — to find that power in yourself and get to fucking work because the water is rising, and so are we.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌠 and 📖

🌠 A game with a mechanic I love.

I really love the Unscene and Echoes in the Night mechanic from The Between by Jason Cordova (a game about Victorian monster hunters in London, inspired by Penny Dreadful).

The Unscene describes a different scene in the same night that is completely unrelated to the main plot and unseen (get it?) by any of the PCs or NPCs. Each Unscene takes place at a different location and is guided by prompts (answered by the players taking turns) and intends to show that a lot more than the PCs plot is going on in London. (It's also a timer for the Night phase but I'm not a huge fan of the strict separation of the Day and Night phases of the game, so we'll ignore that here.)

It ties in with the Echoes in the Night mechanic, which grants you XP when you manage to nevertheless tie the Unscene together with the main plot by echoing an element from one in the other (either way around).

For example, if you first mention the blood-red gloves your character is wearing and then, a little later, describe a theatrical performance that ends with a murderer having blood all over their hands, that's an Echo in the Night.

It incentivizes you to connect images and vibes and not just plotlines, and I think that's a fantastic and very effective idea that I'm just waiting to use in one of my own games eventually.

📖 My favorite class or playbook from a game.

I recently played Dream Apart (a Jewish fantasy of the shtetl) by Benjamin Rosenbaum for the first time, so let's talk about The Midwife.

The Midwife is, well, a midwife. You get to choose a name, a type of hands, an outlook, two advantages, a thing you've seen, someone who you've angered, and 2 shtetl relationships. (Each playbook has different categories in this game.) And that's your Midwife.

You can play Tovah, for example, with stubborn hands and a pantheist outlook (because of course everything is alive in its own way), who has a remarkable sense of smell and the advantage of humility. She may have seen a cottage deep in the forest and have angered the market women by defending the prostitutes (using the game's term her). She may be a young bride's only hope and her lover may have broken her heart.

(Do you see her? Finely attuned to smell the slightest scent of death and disease? Working tirelessly to save as many lives as she can? Being the one the shtetl women go to for contraceptive or abortifacient or soothing herbs and brews? The one who knows about the horse urine and wild licorice? Heart-broken by the woman who left her for a marriage to a man? And always feeling responsible for fixing everyone else's problems and guilty if she can't.)

You can also play Binyamin, for another example, with gentle hands and an idealist outlook, who has perfect memory, and an unflappable sense of humor, despite everything. He may have seen the abbey's catacombs and angered the rabbinical council by defying a ban. He may be resented by the city-educated doctor and suspected by the goyish priest.

(Do you see him? Ever-curious and willing to defy any authority trying to keep him from learning more? Never speaking about what haunts him except in jest? And yet hopeful, steadfast in his belief that a more just world is possible? And lonely, probably a lot more lonely than you'd think.)

The Midwife is blood and birth and death and earthy magic. They're justice and sacrifice and the constant search for balance, within and without themself. Melancholic hope, caring anger, and an awareness of monstrosity, both human and otherwise.

The Midwife makes me think of Granny Weatherwax and Tiffany Aching, of duty and severity, of a plain, practical shell with a core of fiery-soft anger necessary to Do The Work.

It has been a delight to play a Midwife for a few hours, and I hope I'll get to do so again!

#ask me stuff#ttrpg#the between#dream apart#unscene#echoes in the night#midwife playbook#witches gonna witch#sometimes i miss writing poetry

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Ocean Keltoi wrote a thread about what pagans can learn from the Bible. He basically claimed that the Bible is an incredible resource for pagans with regards to magic, offerings, sacrifice, and both historical and mythological storytelling, adding that hatred of Christianity stops pagans from appreciating that and thus "blocks one's ability to grow".

I'm going to be honest, that thread was kind of an L from Ocean. But I will say that the Bible could be a resource, depending exactly on what you're looking for. Because if you're looking for "pagan practice" you're probably not going to find it. Or, if you do, it's largely going to be from the perspective of people who despised the various polytheistic cults and traditions that surrounded them at the time. I suppose if you're looking for something to base Christian magic or the like on, I think it'd be more useful to look into the systems of (again, Christian) folk magic that actually used the Bible in invocations or spell-casting.

But here's what I would prefer to gleam from the Bible, if anything, as relevant strictly to my own approach:

Henotheism in a polytheistic cosmos: Technically, the narrative of the Bible does assume a cosmos in which multiple gods besides Yahweh exist, just that the narrative of the Bible centers around the worship of Yahweh and generally insists upon the sole worship of Yahweh. Indeed, there seems to be a whole council of divine beings who Yahweh presides over, and who gradually lose their stature as Yahweh condemns them. Other gods roam the land, receive worship, and even contend against Yahweh in struggles for power and/or territory. Adam and Eve eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge is explicitly stated as setting them on the path to joining the gods. This creates some ground for "Pagan" treatments of the Biblical landscape, not entirely unsuited to navigating our contemporary religious superstructure. It is also this exact henotheistic landscape that can, with little difficulty, reflect backwards towards the "pagan" cosmoses, often sites of divine rebellion.

Demonology: The Bible is full of demons, alongside its own distinct notion of the demonic. Granted the Apocrypha tend to have a lot more demonology going for them, but the Bible has a wide catalogue of demons that infest the popular imaginary to this day. Christian demonologists have of course frequently derived some of their demons from pagan gods that appeared in the Bible (for example Berith, Adrammelech, Astaroth, Beelzebub, to name just a few) and elsewhere. As Andrew Mark Henry (the Religion For Breakfast guy) noted recently, the demonic has its own way of conveying a sort of outer and/or inner shadow relative to the culture. To pronounce heresy in some ways vivifies that shadow, giving it form and content. The gods, even as demons, speak, even in the voices of demons, their cult, their divine content, and in this form do so in a subversive role.

For that particular point I would suggest a new video on the demonology of The Legend of Zelda. Yes, you heard that right.

youtube

Cosmic pessimism: This part may sound quite strange, but it's very easy to get a throughline of. Granted it's mostly relevant to Christianity, which as far as I can see really doesn't have the benefit of getting to argue with God that Jewish rabbinical tradition actually seems to have. But picture, for classical monotheism at least in "Western" terms, the throughline of a seemingly all-powerful singular deity, who is to be treated as the sole sovereign of the universe. That power, that intelligence, governs the whole of life and its course, and so is invariably responsible for its death. It is also possible to see a constant struggle of humanity with even the divine itself - a theme which can be found more often than you'd think in the Old Testament, but which is poorly appreciated, if at all, by Christianity at large. Whether it's Adam and Eve defying God and being exiled, arguably the story of the Tower of Babel whereby the tower itself is a struggle to connect humanity to the divine which is thwarted by God, Job demanding an explanation from God for all his turmoils before ultimately accepting God's word, or the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel or apparently God itself and being declared victorious by God itself and taking the name Israel as a result, there's actually quite a lot to work with that can furnish an admittedly rugged and darksome perspective on the universe. Not to mention exegesis around the "fall".

But all this is just what I can think of, and if anything a lot of it still assumes a counter-narrative assemblage. What Ocean has in mind to my mind seems altogether different, and the nature of that difference is in some ways the problem. Ocean thinks that the problem of the Biblical narrative is mostly that it was simply used to cultivate a supremacy narrative for Christianity, and I think that's a rather simplistic way to look at it, particularly when, if we're talking about supremacy, the proclamations of the sovereignty of a single god are right there, in the text. Even if it's about use, strictly, if you want to use it for that it's certainly not hard. But then the rest of Ocean's thread is essentially him talking about how witches and magicians invoked verses of the Psalms for example in their magic. But that's not actually in itself "Biblical insight on magic". That's Christians practicing their own variety of folk magic, in the name of the Christian God, probably centuries after the Bible was written. It's just saying that Christians have done magic with the Bible and that it's a part of history so you have to consider it as a pagan, never mind that it might not actually be relevant to your practice as a pagan, because reasons. I would have brought up the Greek Magical Papyri or The Eighth Book of Moses as better examples just because they actually seemed to involve invoking pagan gods like Horus or Helios alongside Jesus Chrestos, Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Iao Sabaoth in some spells while ostensibly still operating around very pagan ideas about religion and magic but hey, that's just me.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archangel Zadkiel

Talon Abraxas

The angel Zadkiel (Hebrew: צִדְקִיאֵל Ṣīḏqīʾēl, 'God is my Righteousness') is the archangel of freedom, benevolence, kindness and mercy, and the patron angel of all who forgive.

In the Sephirot, Zadkiel is fourth, which corresponds to Chesed.

Alternate names

Zadkiel is also known by a variety of other names. Among them are Hasdiel, Sachiel, Zedekiel, Zadakiel, Tzadkiel, and Zedekul.

Abilities and function

In most Kabbalistic grimoires, Zadkiel is the ruler of the Dominions choir in the hierarchy of angels. In rabbinic writings, Zadkiel belongs to the order of Hashmallim. He is considered by some sources to be chief of that order. In Maseket Azilut, it is listed as co-chief with Archangel Gabriel of the order of Shinanim.

Zadkiel is one of two standard bearers (along with Jophiel) who follow directly behind Archangel Michael as the head archangel enters battle. Its magical image is "An angel with four immaculate white Wings, clothed in a long Robe the color of purple, holding a Crown in one hand and a Scepter in the other."

The Grimoire of Armadel states that Zadkiel will teach all the sciences active and passive, with a remarkable facility, with all honesty and courtesy, together with every kind of benediction. They who avail themselves of this angel will possess all things in contentment. He is to be invoked on a Monday morning and is associated with the planetary intelligence of Jupiter.

Abraham's sacrifice

As an angel of mercy, some texts claim that Zadkiel is the unnamed biblical Angel of the Lord who holds back Abraham to prevent the patriarch from sacrificing his son, and because of this is usually shown holding a dagger. Other texts cite Michael or Tadhiel or some other angel as the angel intended, while others interpret the Angel of the Lord as a theophany.

37 notes

·

View notes