#precolonial visayas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

From Museum × Stories at Museo Iloilo:

In the 14th and 15th centuries, pre-colonial Filipinos practiced secondary burials, a fascinating ritual where the bones of the deceased were carefully cleaned and placed in coffins made of hardwood. Archaeological discoveries in caves across Western Visayas reveal that these burials were often preceded by elaborate rites. The presence of deformed skulls in many coffins suggests that cranial modification may have played a role in these practices.

One remarkable find was a burial containing a skeleton adorned with gold eye and nose ornaments, declared a National Cultural Treasure. Called the Oton Gold Death Mask is now displayed at National Museum Western Visayas right beside Museo Iloilo. Alongside the burial, 15th-century Chinese, Siamese, and Annamese porcelain were unearthed, highlighting the region's thriving trade connections during that era.

Also in the town of Oton, other burials revealed a wealth of artifacts, including trade ceramics, locally made pottery, iron tools, beads, and semi-precious stones. Additional discoveries included glass and shell bracelets, earthen net weights, spindle whorls, and teeth decorated with gold pegs—symbols of status and wealth. These finds provide a window into the vibrant cultural and trade networks of pre-colonial Panay.

#philippines#visayas#southeast asia#anthropology#archeology#asian history#iloilo#precolonial#precolonial philippines#precolonial visayas#x

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

datu piri in precolonial visayan attire ✨

#hetalia#hws philippines#hetalia world stars#hetalia fanart#ヘタリア#ヘタリア world stars#ヘタリアws#pre colonial philippines#precolonial visayas

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Cebuana Primadona

The woman behind the clay mask bore the patterns of age-old warriors.

Download the artwork and poem here:

RGB file - patreon link

CMYK file - patreon link

#art#watercolor#watercolor illustration#illustration#filipino#cebuano#cebuano folklore#visayan folklore#precolonial visayas#spanish colonial#colonial visayas#filipino folklore#primadonna

1 note

·

View note

Text

Precolonial Philippines (Visayas Region) - Hatsune Miku

Late to the trend and not 100% accurate in terms of the clothing (still researching on them), but something fun to do outside the main projects.

Timelapse

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

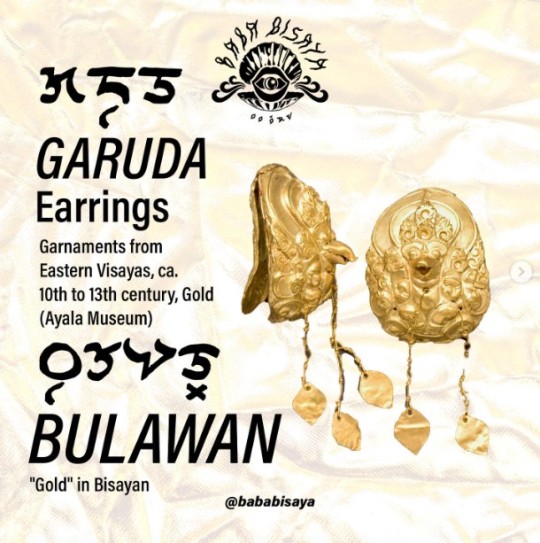

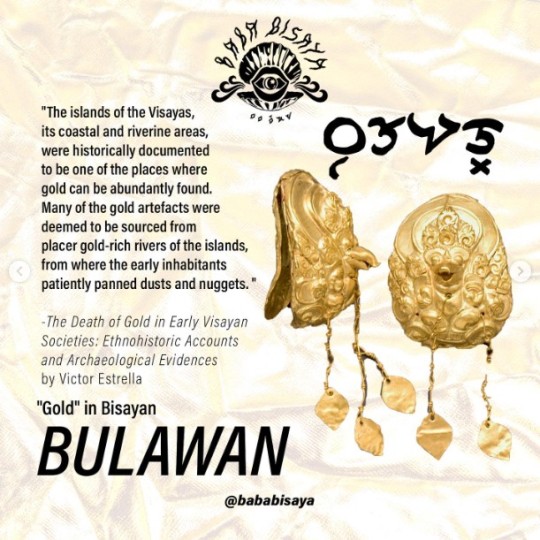

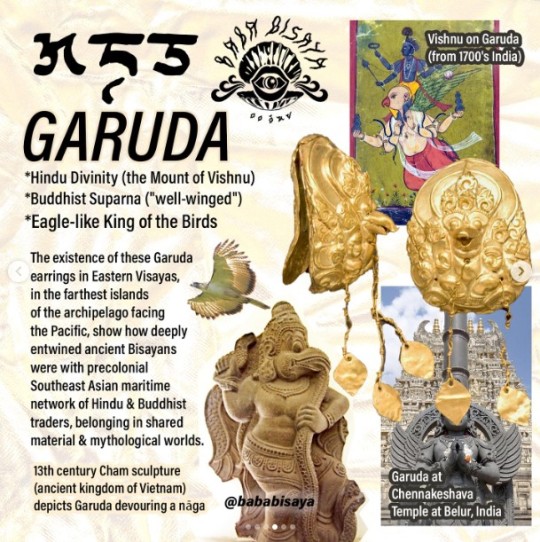

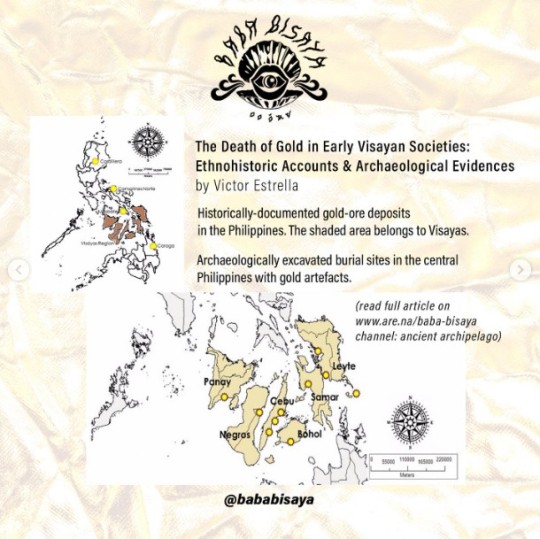

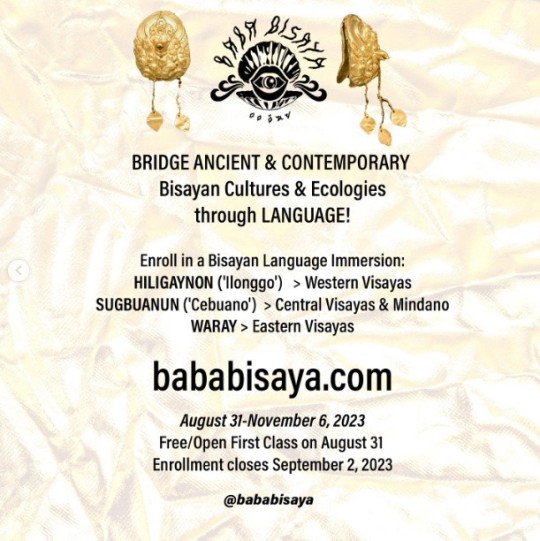

If you go to the Gold Museum in Ayala, you’ll notice how much of the treasures come from the Visayas or precolonial Bisayan kingdoms in Mindanao. We imagine this is only a small sliver of what brilliant gold was once held in the abundant rivers & waters of the islands. Although we can commiserate together about the loss, we treasure what does remain: the richness of our islander languages preserving our living cultures! ⭐️ We’re starting Bisayan Language Immersions next week, from August 31 - November 6, 2023 ➡️ Learn with us! bababisaya.com

Ang larawan at impormasyon ay mula sa opisyal na Instagram account ng Bababisaya.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

June means pride month but it also means that the Philippines’s Independence Day is coming up so I wanna start my art line for June by drawing the noodle bois, Veneer and my oc, Gloss, whom I shipped together in precolonial Filipino outfits, complete with jewelry and in Gloss’s case, tattoos since Zircon is the leader and tattoos in the precolonial era are a symbol of high status. It was hard to design the tattoos because the designs vary from the Kalinga, northern Luzon, Visayas, and all over the Philippines.

Plus, while reading the history of my home country, I found out that before the colonizers from Spain arrived with their narrow-minded ideals, homosexual relations in both sexes were common and bore no stigma in pre-colonial Philippines, which was no big deal for my ancestors. I can't believe this part of history was erased by the colonizers and forgotten for many years.

Background: https://www.carls-sims-4-guide.com/gamepictures/expansionpacks/islandliving/1butterflies.jpg

#dreamworks trolls#trolls band together#trolls oc#mount rageon#rageon oc#trolls veneer#gloss#precolonial philippines

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

as nice as the message is, this falls into the “feel-good” trap of precolonial history-telling.

this person is homogenizing the multiple and distinct polities of the prehispanic philippine archipelago with the language of “our culture.”

the gender relations throughout southeast asia may have valued women’s labor more than our contemporaries in, for example, south asia at the time, but that does not make precolonial philippines—nor most of southeast asia—a matriarchy.

not all shamans were called babaylan (this is a visayas-specific term) and not all babaylan, catalonan, and other shamans were of a third gender.

i’d like anyone interested in philippine and southeast asian histories to check out barangay by william henry scott, the flaming womb by barbara andaya, and southeast asia in the age of commerce (vol. 1) by anthony reid. there’s lots of information about the positions of women and feminine persons in pre- and early colonial southeast asia! and let’s not forget, plenty of gender variants exist among modern southeast asians such as in bugis society, albeit suppressed by rising religious bigotry.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring Region VI: The Western Visayas

Region VI, known as Western Visayas, is a vibrant region in the central Philippines, comprising six provinces: Aklan, Antique, Capiz, Guimaras, Iloilo, and Negros Occidental. It is celebrated for its picturesque landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and flourishing agriculture.

Geography and Natural Wonders

Western Visayas boasts a diverse geography that includes white sand beaches, rolling hills, verdant mountains, and lush rice fields. The region's most famous destination is Boracay Island in Aklan, known for its powdery white sand beaches and crystal-clear waters. Antique offers unique experiences like the Kawa Hot Bath and treks to the majestic Mount Madja-as. Guimaras is renowned for its pristine beaches and its world-class sweet mangoes, celebrated in the annual Mango Festival.

In Negros Occidental, you’ll find the mesmerizing Sipalay beaches, while Iloilo is home to Islas de Gigantes, a group of islands featuring dramatic limestone cliffs and turquoise waters.

Culture and Heritage

Western Visayas is steeped in history and culture. Iloilo City, often called the "City of Love," is known for its historic churches, heritage houses, and the Dinagyang Festival, a grand celebration honoring the Santo Niño. Meanwhile, Capiz, often referred to as the "Seafood Capital of the Philippines," showcases a blend of Spanish and indigenous heritage through its culinary offerings and historical sites, including the iconic Pan-ay Church.

Antique’s Binirayan Festival reenacts the ancient arrival of the Bornean datus, reflecting the region's rich precolonial history.

Cuisine

The region’s culinary landscape is as diverse as its geography. Must-try dishes include:

La Paz Batchoy: A flavorful noodle soup originating from Iloilo.

Chicken Inasal: A marinated and grilled chicken dish, famous in Bacolod City, Negros Occidental.

Seafood Galore: Fresh crabs, oysters, and mussels in Capiz and Guimaras.

Piaya and Napoleones: Sweet delicacies from Negros Occidental.

Economic Contributions

Western Visayas thrives as an agricultural hub, producing rice, sugarcane, mangoes, and seafood. Negros Occidental is dubbed the "Sugar Bowl of the Philippines" due to its vast sugarcane plantations. Additionally, the region supports a robust tourism industry, with Boracay as a major international draw.

Handicrafts and weaving are also significant industries, with Aklan's piña fabric being a standout export.

Tourism and Development

The region is a growing center for sustainable tourism. Efforts to protect its natural resources while promoting eco-friendly activities have been evident in initiatives like marine conservation in Aklan and sustainable farming practices in Guimaras.

Conclusion

Region VI, Western Visayas, is a captivating blend of natural beauty, cultural heritage, and modern vibrancy. From its iconic festivals and historic sites to its breathtaking islands and delectable cuisine, it offers an unforgettable experience for locals and tourists alike.

0 notes

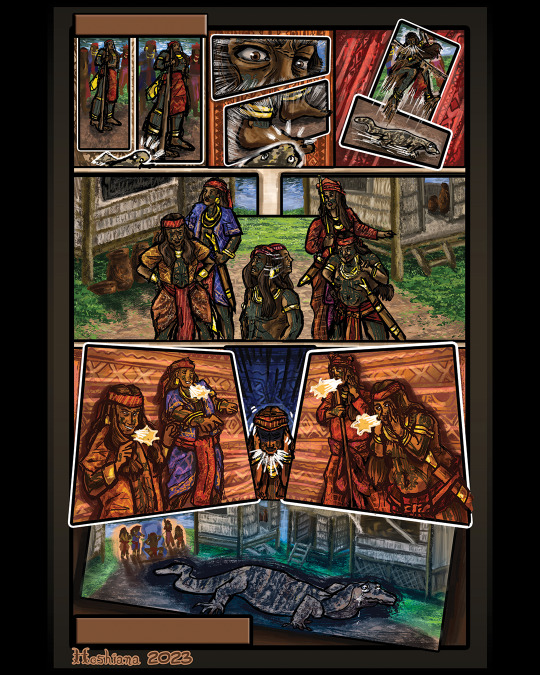

Photo

Finally, I managed to finish another comic panel preview for my comic series, "Ang Handuraw ni Hoshiana". Is there a relationship between warriors with tattoos and a monitor lizard in the precolonial Visayas? You will discover this in the upcoming month of June! Be sure to stay posted for upcoming information! I plan to be more active between June and August. Expect to see new artwork(s) or content(s)!

#digital art#digital illustration#digital artwork#comic#comic panels#adobe photoshop#illustration#art preview#art#artists on tumblr#artwork#comic preview

1 note

·

View note

Text

He has clothes now

spent a couple of hours gathering filipino traditional full body tattooes

there are a few hidden at his thighs

no i cant draw feet or hands

the tatts aren’t even finished yet but here’s some of the details that got hidden

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah, it’s technically inaccurate to talk of a “precolonial Philippines” because the name itself literally came in at the onset of colonization. That’s on top of the modern geographic confines of the archipelago we know now as the Philippines.

I feel that this will be PhD-level research (because I need to look for resources in languages I have absolute zero fluency in, and in places that need me spending a lot to travel to and from there), but as far as I could mindlessly look up online, I bumped into Panyupayana as a supposed name.

Joefe B. Santarita, “Panyupayana: The Emergence of Hindu Polities in the Pre-Islamic Philippines.” In Cultural and Civilisational Links Between India and Southeast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Dimensions, ed. Shyam Saran (Singapore: Palgrace Macmillan, 2018), 94.

The same version of the map was in K.M. Panikkar’s Survey of Indian History, but as far as I got to quickly scan through it, the author doesn’t discuss the specific Indian literature they sourced the name from, nor even mentions Panyupayana anywhere else in the same book. The only other (secondhand) source cited doesn’t exist — in the sense that if it was accessible online, that’s been obliterated. Basically, I’m in a dead end in terms of reading more into this. The other thing to note is when these claims were published — which was a time of burgeoning Asian unity. Not bad in itself, just understand that nationalism can get ugly real quick.

Anyway, I roll with having a precolonial Piri for shipping excuses. 😭 Personally, I treat historical accuracy as a tool to supplement whatever themes & ideas I want to entertain in storytelling.

Otherwise, I’m entertaining — for lack of a better term — Philippine OCs. I’m obsessed with how ethnolinguistic groups are also called nations. I just don’t have the (luxury of) time to develop them, let alone draw them. I wouldn’t call them a “family” either, in the strictly biological sense. Maybe, at least, not all of them have that particular relation. But I will say that the general dynamic they have with one another, including Piri, is more or less the kind of chaos and drama that can happen during family reunions. I know my Filipino homies should get this.

Btw, for resources on precolonial history of the Philippines:

William Henry Scott is your token guy. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society is pretty much textbook material, but he also has Looking For The Prehispanic Filipino and Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History.

The Boxer Codex

Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World, 1519-1522: An Account of Magellan's Expedition

F. Landa Jocano, ed., The Philippines at Spanish Contact: Some Major Accounts of Early Filipino Society and Culture

Blair & Robertson is research-beginner-friendly, but it's not only 53 volumes (plus 2 as indices), it's not the most reliable either because it's compiled and edited by Americans, so biases might have twisted things here and there.

P.S. Keep in mind that most of them are concentrated within the Visayas and central Luzon areas!

ive been wondering about how philippines childhood would be lately because while i think its not lore-accurate or historically accurate for him to represent the entirety of the archipelago precolonially, the "england-america" route of spain raising him also feels inaccurate in a way

my personal hc is that he appeared after spain arrived on the islands, but there were other nations inhabiting it beforehand doing funny and crazy history stuff. it might be fun to explore the topic through ocs, but there is so little info i could find about precolonial ph :(

idk, filipinos and phili-fans, what are your headcanons? 🤔

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

[long post] finally watched the kingdom (2024), here are my thoughts:

1. as i expected, it had very weak worldbuilding.

the point of divergence from real world history to their fictional history was the three paramount rulers of luzon: rajah matanda, rajah sulayman, and lakan dula existed. the current dynasty is descended from lakan dula and the seat of power for the kingdom of kalayaan is in manila. therefore, the characters are tagalog (and kapampangan?) descent — yet they utilize aspects of classical visayan culture for an inexplicable reason: the tattooing culture, the employment of babaylans rather than catalonans, and the bakunawa motif.

despite the oft-times awkward placement of exposition throughout the film, there is none provided to explain how it is that spanish and other european & american powers failed to colonize the archipelago. was it a coalition of asian powers (e.g. filipino-chinese-japanese) against european ones? or were europeans already weakened at the time of the would-be conquest? was it a matter of manpower or technology? diplomacy and collaboration with foreigners in exchange for nominal freedom?

in addition, there’s no explanation for why the modern tagalog culture resembles classical visayan ones more than their own. if rajahs matanda and sulayman & lakan dula existed and resisted colonization, then it only makes sense the current population would only be muslim as these rulers were increasingly islamized. rajah matanda is famously related to bruneian royalty. tagalog elites ceased growing their hair long, ceased eating pork, and ceased tattooing by the time the spaniards came. the general population was still animist-polytheistic, but realistically they would come to accept islam just as their rulers did without the implementation of catholicism by spanish proselytizing.

i think the people behind this film were either too attached to the visayan image of a precolonial philippines or too scared to alienate their majority christian viewers by portraying a muslim-majority alternate philippines. they even forego using malaysia and indonesia as cultural inspirations and relied on the monarchal thailand instead.

also, again there is no explanation as to how the kingdom of kalayaan includes visayas and mindanao — nor why they are still called that. (“mindanao” came from the corruption of “maguindanao” after the maguindanao sultanate which, at the time of the colonial writers describing the land, ruled majority of the island. if there were no colonization though, then it must be called something else OR the maguindanao sultanate somehow encompassed the whole of the island at its fictional peak.) classical visayans rejected islam whereas mindanao was split between muslims and animists. it makes no sense to have disparate ethnoreligious groups in all three major islands to unite under the same manila-based animist monarchy.

there is, however, some interesting and casual shows of culture and customs. for example, igorot men wearing their traditional attires without humiliation from non-igorot characters living in the cordilleras; the prince being served alcohol by a servant who presents it with two hands while bowing; and the elevation of sabong as a hybridized boxing-wrestling sport.

2. the beginning scene (i.e., native fishermen being illegally apprehended by a foreign navy; a thinly veiled allusion to chinese harassment of filipinos in the west philippine sea) is too on-the-nose, as with other scenes in the film.

in the beginning, for example, we see villagers discussing who they wish to succeed the king. the camera pans to merchandise worn on their bodies, e.g., rubber bracelets announcing their “team.” very reminiscent of the previous election.

3. it’s an action-heavy production but the camera work, direction, choreo, and/or editing amount to very stilted scenes. regardless, the acting — especially from cristine reyes and piolo pascual — were believable.

4. little time to explore the deeper motivations and backgrounds of the antagonists. there is a separatist movement but it ends before the film does; we meet only the leader of the otherwise faceless movement. there is then a plot twist and a post-credit scene involving a different antagonist.

the themes as well! towards the end the writers introduce the concept of the fallibility of memory, which unfortunately amounted to little emotional impact due to restricted time and no hints leading up to its reveal.

tl;dr: this could have been better if the worldbuilding were different and if it were a limited series instead of a film.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

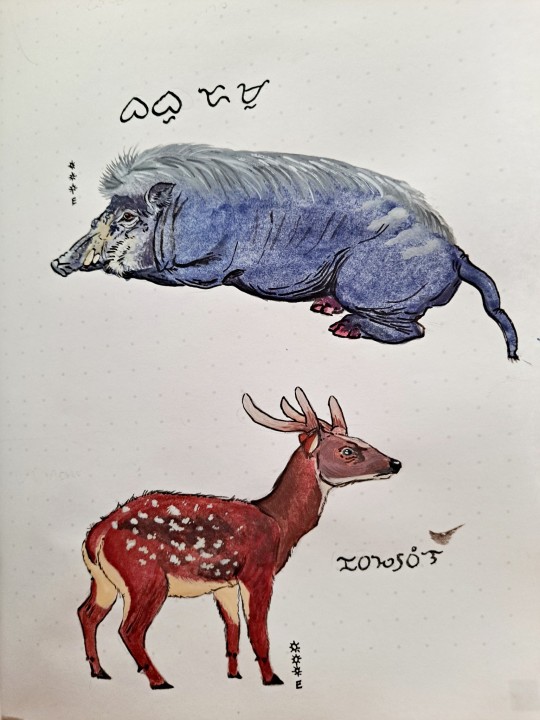

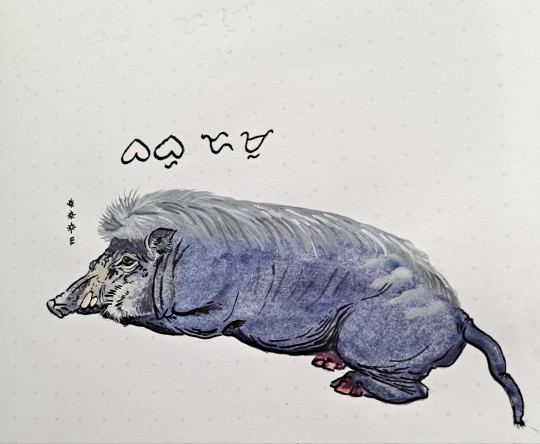

These two are endangered but fascinating animals native to the Philippines, the Philippine Warty Pig (Baboy damo) and Visayan Spotted Deer (Kabang binaw) found in as you probably guessed, the Visayas.

As for the writing, pre-hispanic Philippine scripts are usually collectively described as suyat or surat- alphasyllabries which allowed entire islands to be literate. The script itself is descended from Kawi, a brahmic system one used my most Southeast Asian languages before diverging into scripts like Old Javanese and Sumatran.

I wrote Baboy Dano in the precolonial form of Baybayin (Tagalog Script) which drops final consonants and does not have characters for introduced words

Kabang Binaw I wrote in Suwat Bisaya, the specifically bisaya script using the post-colonial panantang pantingog to kill the final vowel.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

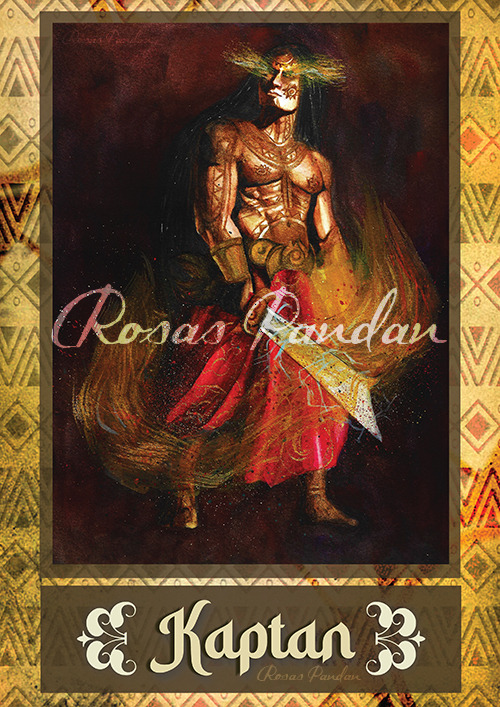

Balahala'ng Kaptan

Balahala'ng Kaptan (The lord Kaptan), is the Visayan's supreme diwata (deity) of the heavens. He is the primordial father of the old pantheon and bears the power of lightning and fire.

More about him on my Patreon!

https://www.patreon.com/posts/hulagway-study-73934126?utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=postshare_creator

#visayan mythology#mythology#filipino mythology#precolonial philippines#precolonial visayas#kaptan#diwata#devata#balahala#Kaptan#watercolor#watercolor illustration#gods and goddesses#deities#history#filipino culture#filipino history

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Not all stories etched with ink and blood were on paper. I just think he gets to keep something.”

Physical Appearance (Tattoos) Headcanons for HWS Philippines

CW: war, violence, mentions of sex

(I'm sorry that sounds like clickbait... it's on the topic of feats that merit a tattoo).

UPDATE (03/09/23): Minor revisions to PH script tattoos

☼ ☼ ☼

Age of Eligibility for First Tattooing

Manobo: 10-12 years (pre-puberty) Kalinga: 15-20 years (“coming of age”) Visayan: ~20s (adulthood)

Order of Significance

Manobo: N/A; forearms, back, & chest for men (Only women could tattoo their abdomen and calves as well; interestingly among the 3 styles, tattooing on men's abdomens was sparse, if not left completely blank) Kalinga: Wrist —> Back of hand —> Arms —> Chest (+option: sides of torso/legs) —> Back —> Face Visayan: Ankles -> Legs -> Waist -> Chest -> Back -> Face

My idea of tattooing order for Piri would be as such:

Arms, from the wrist (Manobo)

Legs, from the ankles (Visayan)

Chest (Kalinga)

Back (Kalinga)

By tradition, the tattooist decided on the motif, but recipients could also pitch ideas. Piri's script tattoos were his suggestions.

A fully-tattooed arm would take 1 day to complete, while a Kalinga chest whatok was worth 3 days. The tattoo session could even be halted midway, and either the client expressed to resume on another day or simply ended the process altogether. Men would sometimes deliberately hold back on getting tattooed, but this was not without a buildup of peer pressure over time.

Piri got his forearm pangotoeb while young (for a personification) because he wanted to be like the cool, older folks. Poor baby boy would fail to immediately realize how much the process hurt, and he would frequently make up excuses to delay his sessions.

By the time Piri got his leg tattoos, he would gradually fill them up alongside his upper arms, depending on whether he was wandering around the Visayas region or at the Pantaron mountain range down in Mindanao. For sure, Piri received his Kalinga whiing (chest) and dakag* (back) after those parts had been inked.

Notice how I gave him tattoos from Luzon (Kalinga), Visayas, and Mindanao (Manobo)? Hehe.

What constituted getting a tattoo was not exclusive to warfare achievements or headhunting boons. Anything could be a reason for getting a tattoo, as long as the community itself acknowledged it as valid merit.

What exactly did Piri achieve to earn his tattoos? He changes the story every time you ask him.

Was his butt also inked? Yes. I won't show it for fear of unwittingly getting the boot from this platform.

☼ ☼ ☼

Buhid, Tagbanwa, and Kulitan never had a virama (the sign for canceling the inherent vowel). There had been attempts to introduce it in the latter two scripts, but it was never successfully mainstreamed. In writing syllables with canceled vowels, one must retain the original syllable in Tagbanwa and Kulit while you no longer had to write the syllable itself in Buhid. Viramas for Baybayin and Hanunó’o were introduced after the precolonial era, neither of the attempts accomplished by native Filipinos.

In taking these scriptwriting nuances into account, one should enunciate the script as it was being read to discern the word being referred to. Even though it was written as “wa-nga-ya”, a Buhid native would naturally understand it to be read as “way ngayan.” Although anyone could attempt to write in any language with these scripts, I wanted to stick to the intended native tongues to showcase how to properly interpret them.

After doing a guided tour in the National Museum of Anthropology, I opted out of using the "modernized" writing systems in exchange for the "historically utilized" method of not including viramas or writing out a character altogether to eliminate the vowel.

☼ ☼ ☼

TRANSLATIONS

Baybayin: Sumpa Kita (Tagalog) - “I Swear”

Depending on the tone, you could be proclaiming a promise or a curse. I love it. It was also the phrase that the name of the Philippine national flower, (sampaguita) originated from, which was also one of Indonesia's national flowers (melati putih). IndoPhil fans, start taking notes.

Kulitan: Tadtad (Kapampangan) - “To cut to small pieces (minced, diced, pinked, etc.)”

There was a saying: "Tadtaran decoman, ing catadtad a mitalandang, iyang maquiasaua queya." It could be roughly translated as: "They me cut me into a million pieces, but even one of those pieces is still good enough to marry 'the one.'" Morbid but romantic, and reflective of Piri’s love for Indo (he’d be that cheesy, okay?)

Tagbanwa: “Tablay” - “To cross hills and mountains”

It was a 4-verse song that narrated a variety of topics, ranging from household chores to community gatherings to expeditions to sentiments (positive or negative) for others. Penultimately the tablay served to express “what comes out from the heart.” That was so quintessential Piri.

Hanunó’o: “Harampanan” - “Discussion”

What was interesting was that the same term referred to both the conversations held in settling disputes and the moment of convening between the parents of a couple to consent to their marriage (or not). He might be a social butterfly, but he was constantly under pressure to fulfill the role of an intermediary.

Buhid: “Way Ngayan” - “No name”

I initially drew a different word and decided to change it as it didn’t fit for Piri to carry something he could never wield. Among the highland Tau-Buhid, it was common practice to answer “way ngayan” when outsiders of the community asked for their names. Instead, the outsiders would give a name to the Tau-Buhid being addressed to, and only then can the Tau-Buhid be allowed to speak to them. It’s funny how the Philippines was a name* christened by an outsider.

*The same goes for my headcanon name for precolonial Piri.

☼ ☼ ☼

The first name in the tattoo styles referred to the specific location of residence of the studied ethnolinguistic group. It was not a strict requirement to note it down at all times, but more often than not these groups identified themselves by their location.

Supposedly the Panay-Bukidnon/Suludnon preserved precolonial Visayan tattooing, but the one source I found online described it to be more of a freestyle practice. I was also unable to find images of the tattoos on the people themselves. Nonetheless, there was the Pintados Festival that paid homage to the titular tattooed warriors.

I wanted to point out the visual similarities because tattooists were also traveling practitioners to find clients for their work. It was a possible explanation for why tattooed people (if not the particular tattoo style) were observed across the Visayan islands as well as parts of southern Luzon. In the late 19th century, some Bagobo people shared that they were tattooed by an outsider practitioner. Whang-od herself used to be a traveling tattooist.

This was speculation on my part but I believed it was also possible that tattooists also took inspiration from other styles. Chest tattoos for men in both the Visayan tattoos and Manobo pangotoeb both had radial designs on the areola (which I did not draw for Piri’s chest tattoos simply because they clashed). Who knows, maybe a Manobo tattooist encountered the Visayans and wanted to create their version? I liked to think that the variations in motifs and pattern combinations could double as a tattooist's signature.

I allowed for a few liberties here and there in drawing some tattoo motifs for Piri because, at the end of the day, inspiration could come from anywhere. One could also say the variation lies in how artists created their visual interpretations of the sources of inspiration. Even the Kalinga tattoos made available for tourists are borrowed imagery from other groups! In the past, one Kalinga warrior had an eagle tattoo on his arm that was based on the image on an American coin.

Tattoos were meant to be unique to the individual. Their value on having to be earned was on the basis that they reflected not just the personal histories (if not necessarily achievements) of the wearer, but such histories must also be acknowledged by the community granting them.

That last bit was important because while anyone could pay to be tattooed (and it would still represent something about you), you would be considered a fake. Hiya (shame) was a thorn that penetrated deeper around these parts. Although only the Manobo did not have a stigma for not being tattooed, the social pressures still left a mark on Piri (literally!)

If one relied only on tattoos as a visual cue, one would be unable to distinguish which groups individuals belonged to from a distance. If every one of the most significant leaders were tattooed in the exact same patterns, it would be impossible to recognize who’s who until they formally introduced themselves (which no one would have the time for in the middle of combat!) The Visayans had a set of tattoos that could be used by all, which implied some designs were restricted only among the best of the best.

This was HWS Philippines. If he’s going to be the star, he needed to stand out from the crowd.

It would, however, be awkward for Piri when he spent time with certain other groups that carried a strong contempt for the ones he received his tattoos under. He would not be exempt from the consequences.

☼ ☼ ☼

Now here was one more reason why artists/designers should not be afraid to modify on the tattoo motifs (as long as one familiarized themselves with the foundations they worked with): The Butbut Kalinga believe it was taboo to copy older designs, all the more if the original recipient was deceased. So in letting a character don some Kalinga whatok, think twice about perfectly copying every last detail from reference image/s!

In the present day, tattoos for visiting tourists from Whang-Od had to make a selection from a prepared guide, all of them modified for a general audience v.s. designs exclusive to esteemed warriors of the past. I used the former for Piri’s Kalinga whatok.

This was where I addressed the elephant in the room.

My understanding of cultural appropriation was that the offense is in cherry-picking culturally significant symbols & practices and then using them out of their intended context by transforming them into pieces that fit the aesthetic criteria of the dominant - and often oppressive - group.

Save for that one taboo, I did not find any other explicitly recorded statement from either the Butbut Kalinga or the Pantoron Manobo forbidding outsiders from using their tattoos. (Mind you, this was all via resources I could access online - screw this pandemic!)

There was also the lingering question regarding the cultural preservation of PH tattooing practices. In the case of the Kalinga whatok, considering that we could not simply reintroduce headhunting in the present day for morality reasons, did that not mean the tattoos had essentially lost their cultural context? If that rendered them invaluable objects, would it not be self-defeating to the purpose of cultural preservation to just let the practice die out?

I sincerely believed it was just as patronizing to assume that even indigenous peoples could adapt and re-contextualize their traditions because it did not fit the (outsider) ideal of preserving their [I am knocking on wood here] "pristine, primitive forms."

Sometimes even good intentions/aspirations could still take away the platform from the ones it was built for.

(I know I just sounded like a hypocrite in saying that so I'm beating you all to it and calling myself out on it.)

☼ ☼ ☼

My biggest motivation for manifesting this headcanon at all was because I did not swim with the fanon of amnesiac Piri. 😭💦

I was at odds with what constituted as a collective (national) memory, all the more when not only was the Philippines as the nation we knew today was a far cry from the "nation" (bayan) that existed 1500+ years ago (and that was if you happened to go there, which I do because I also did not swim with chibi Piri by the time Magellan showed his ass up on our shores).

It sucked that we lost much of the perishable writings from that time, but written works were not the only means of cultural/historical preservation. I also disagreed with the implication that only written works counted as a valid archive.

The pen might be mightier than the sword, but efforts to improve literacy skills were a double-edged sword in itself. While it was important to teach people to be better communicators*, measuring intellectual capacity by literacy skills could get problematic. I condemned this assumption because I sincerely did not believe that precolonial Filipinos being unbothered to keep written records was a sign of their “backwardness.” What if they never felt the need to?

Because why bother writing it all down when you could say it out loud instead! We might not have books and written histories, but we got oral histories! Epics, ballads, hymns, riddles, folklores, you name it! People passed down traditions through storytelling, all the more for all the indigenous natives* residing in the nation that resisted imperialistic rule (not just colonial) for centuries! We were a nation of songbirds! And that was why "Piri chronically online on Twitter" was absolutely valid.

Although it was easy to justify the amnesia take because the colonizers massacred so many people, and without the people, you also lost the very guardians of those memories...in my most honest opinion that...registered poorly in my head.

What of the ones who survived? What of the people who lived to tell their tales?

When did we stop listening?

*More often than not, people grew up to be swayed to unwittingly support imperialistic/capitalist/fascist agendas because very subtle propaganda was discreetly inserted into the lesson plans in their formative education. Criticisms on colonial education deserved their own talk for another day.

☼ ☼ ☼

What constituted a memory was the affection, the emotion that came with certain experiences. It was why some memories persisted while others were easily forgotten. It was why even memory recollection (which indicated an active search) might not necessarily be true or not. Memory, both in itself and the processes surrounding it, did not follow a linear & and straightforward path (and that was already without taking the complexity of neurobiology into account).

While the merits for a tattoo were generally prescribed through specific or notable acts, I noticed that majority of them seem to share one common affection: Passion. The feeling of an intense, compelling desire for something (or someone).

Among the Manobo (today), most of them were compelled by aesthetic reasons in getting a tattoo. The desire to maintain an appearance that would equally leave an impression on others.

Headhunting/warfare was just the easily cited method, but the Kalinga appraised any act that denoted an individual’s bravery & valor. Bravery in fighting the frontlines, fueled by the compelling desire to defend one’s homeland.

Violence** born out of vengeance is also a thing, and vengeance was just passion manifesting negatively.

Precolonial Visayans had names for tattoos that marked an individual’s first-time experience in war…or love (sex, I guess). Two polar forces treated as equals. I think of how Aphrodite/Venus was also a goddess of war. A goddess of passion.

Headhunting could also have gendered notions that display the "mutual dependence" in the dichotomy of "male/female bloodshed." In a study of the Huaulu people (Seram, Indonesia*), they had a taboo where the men could not participate in headhunting if their wives were menstruating or giving birth. This reinforced the idea that women as "bleeding humans" were as powerfully influential as men who were "bleeders of humans."

On a similar note, there was a pervasive belief in certain other groups that headhunting blessed communities with fertile lands (alongside fertile women). Blood as life essence. Blood as a source of vitality.

Sometimes passion is comparable to being a force of vitality. The driving force of life and death.

Hades game Achilles was onto something when he wrote that Aphrodite "may be the mightiest of all [the Olympians]."

It got complicated, however, because headhunting and warfare were also a means of state violence**. The precolonial Visayans were engaged in and subjected to slave raids, born out of the need to harvest labor for trade motivations (fuck capitalism, am I right?). If all the battle experience from such activities counts as a merit for tattoos, what did that make of Piri?

I thought of how even blood was shed during the process of tattooing. In a way, Piri’s tattoos also functioned as a reminder of all the blood that was shed for him. A reminder of all the people who died for their passions.

Whether it was a price worth paying or not is a conflict he may never find a resolution for.

*They were comparable to the Buaya (Kalinga) in the shared gendered aspect in headhunting. While this implies a cultural backing to Beyer's Wave Migration Theory, the latter was contested by W.H. Scott. In the cited studies below that concentrated on Kalinga tattooing, there were no further details given regarding any connected symbolisms to headhunting.

**Just so we’re all clear, me conducting frank discussions on the topic of violence DID NOT equate to me condoning violence. Remember that Kalinga tattooing diminished because headhunting was outlawed for its nature as an act of violence.

☼ ☼ ☼

Fortunately, there was always the option to negotiate out of a fight (nail that persuasion check, Piri!!).

This was where tattoos as an indicator of one’s place in a community came into play: the more tattooed an individual, the more highly regarded they were. It was they who act as the primary mediator for any conflicts that arose.

It was a huge burden to bear for an entity that encompassed so many communities when he was not (exactly) a part of any of them. While his tattoos provided an opportunistic signal for Piri to be treated as someone due equal respect, it also made him vulnerable to open contempt. Righteously so when the community in question had been victims of the same state violence that advocated for a united nation.

Even prejudice could exist within the same group of people: between those who were content interacting with “lowlanders”/”outsiders” and those who adamantly remained isolated, with the latter even denying the “Filipino” identity. However, a people’s resistance in identifying as subjects of an oppressive government should not be cause to disregard their (co-)inhabitation of spaces. Mediation became a necessity to maintain harmonious relations.

It was a struggle that remains a constant throughout Piri’s history. Juggling the roles of the mediator between communities and the warrior who defended these communities.

The tattoos served as an eternal reminder of Piri’s passions to uphold all these narratives. A reminder of his purpose to maintain the fine threads between peace and war.

HA! I REALLY CAME BACK FULL CIRCLE TO THE FLAG SYMBOLISM!

☼ ☼ ☼

Speaking of flag symbolism, allow me to end this brainrot essay on a funny note.

Imagine telling HWS Philippines that the sun on his flag was inspired by his ASS TATTS.

☼ ☼ ☼

Sources

Abbacan-Tuguic, Lalin, and Lunes Marnag. “Whatok (Tattooe): The Aesthetic Expression of Traditional Kalinga Beauty.” International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences 5, no. 6 (2016): 725-939. https://garph.co.uk/IJARMSS-vol5-no6.html. Bergaño, Diego. Vocabulary of the Kapampangan language in Spanish and dictionary of the Spanish language in Kapampangan: The English Translation of the Kapampangan-Spanish Dictionary. Translated by Fr. Venancio Q. Samson. Angeles City, Philippines: Holy Angel University Press, 2007. Boxer Codex: A Modern Spanish Transcription and English Translation of 16th-Century Exploration Accounts of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Edited by Isaac Donoso. Translated by Ma. Luisa Garcia, Carlos Quirino, and Mauro García. Quezon City, Philippines: Vibal Foundation, Inc., 2016. Bramhall, Donna. “Exploring Kalinga culture, tattoo artistry, tribal traditions,” Rappler, July 9, 2016. https://www.rappler.com/life-and-style/138427-kalinga-culture-tribal-traditions-tatoos/. Calano, Mark Joseph. “Archiving bodies: Kalinga batek and the im/possibility of an archive.” Thesis Eleven 112, no. 1 (2012): 98-112. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0725513612450502. Clariza, Ma. Elena. “Sacred Texts and Symbols: An Indigenous Filipino Perspective on Reading.” The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion 3, no. 2 (2019): 80-92. https://doi.org/10.33137/ijidi.v3i2.32593. Cultural Center of the Philippines. “Tagbanwa.” Encyclopedia of Philippine Art. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/1/2/2374/. De Las Peñas, Ma. Louise Antonette N., and Analayn Salvador-Amores. “Enigmatic Geometric Tattoos of the Butbut of Kalinga, Philippines.” The Mathematical Intelligencer 41, no. 1 (2019): 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00283-018-09864-6. Garlitos, Rhandee. “Great Elder.” Panyaan: Three Tales of the Tagbanua. Accessed Dec 7, 2021. https://www.canvas.ph/catalog/panyaan-three-tales-of-the-tagbanua. Hoskins, Janet. “Introduction: Headhunting as Practice and as Trope.” In Headhunting and the Social Imagination in Southeast Asia, edited by Janet Hoskins, 1-49. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1996. Krutak, Lars. “The Last Kalinga Tattoo Artist of the Philippines.” Lars Krutak: Tattoo Anthropologist (blog). WordPress. May 30, 2013. https://www.larskrutak.com/the-last-kalinga-tattoo-artist-of-the-philippines/. Miyamoto, Masaru. 1988. “The Hanunoo-Mangyan: Society, Religion and Law among a Mountain People of Mindoro Island, Philippines.” Senri Ethnological Studies, vol. 22. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology. Ocampo, Ambeth R. “Who owns Whang-Od and her tattoos?,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, August 11, 2021. https://opinion.inquirer.net/142977/who-owns-whang-od-and-her-tattoos. —. “Heritage: More heat than light,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, August 13, 2021. https://opinion.inquirer.net/143039/heritage-more-heat-than-light. Pagador, Renan. “The Philippine Scripts.” Baybayin Archives (blog). Blogspot. August 26, 2020. http://rapcom-archives.blogspot.com/2020/08/. Ragragio, Andrea Malaya D., and Myfel D. Paluga. “An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos.” Southeast Asian Studies 8, no. 2 (2019): 259-294. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.8.2_259. Rosales, Christian A. “Sorcery, Rights, and Cosmopolitics Among the Tau-Buhid Mangyan in Mts. Iglit-Baco National Park.” Aghamtao 27, no. 1 (2019): 110-159. Salvador-Amores, Analyn “Batek: Tradition Tattoos and Identities in Contemporary Kalinga, North Luzon Philippines.” Humanities Diliman 3, no. 1 (2002): 105-142. https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/humanitiesdiliman/article/view/32. —. “Batok (Traditional Tattoos) in Diaspora: The Reinvention of a Globally Mediated Kalinga Identity.” South East Asia Research 19, no. 2 (2011): 293–318. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23750924.

—. “Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines.” In Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing, edited by Lars Krutak and Aaron Deter-Wolf, 37-55. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017. —. “Re-examining Igorot representation: issues of commodification and cultural appropriation.” South East Asia Research 28, no. 4 (2020): 380-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2020.1843369. Scott, William Henry. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994. “Visayan Tattoo Design.” Akopito (blog). Weebly. February 18, 2014. http://akopito.weebly.com/blog-naacutekocirc/visayan-tattoo-design.

Final Note

While they were interconnected, the emphasis of my headcanon was on tattoos as (national) memory over tattoos as (national) identity. I know it's paradoxical of me to separate them but it did make you think twice about what built identity. What built character! It's a question I cannot answer through one headcanon or one comic even. ☼ BANAAG ☼ would be my attempt at a personal answer to that question.

#hws philippines#war cw#mentions of sex cw#hcs: physical appearance#cultural features#long post#cultural hetalia#hcs: hws philippines

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you go to the Gold Museum in Ayala, you’ll notice how much of the treasures come from the Visayas or precolonial Bisayan kingdoms in Mindanao. We imagine this is only a small sliver of what brilliant gold was once held in the abundant rivers & waters of the islands. Although we can commiserate together about the loss, we treasure what does remain: the richness of our islander languages preserving our living cultures! ⭐️ We’re starting Bisayan Language Immersions next week, from August 31 - November 6, 2023 ➡️ Learn with us! bababisaya.com

Ang larawan at impormasyon ay mula sa opisyal na Instagram account ng Bababisaya.

3 notes

·

View notes