#polygamy in egypt

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bit of lore about marriage

Okay, I can see that this marriage rights thing may be confusing, so here are some bits of lore that I already wrote about on my patreon (and you can also find it in history books about the era):

Polygamy was allowed to a certain degree in Ancient Egypt and this didn't just include the king.

Male members of a marriage were allowed to have concubines next to their official wife/spouse. These concubines were not married to them, because only the pharaoh was allowed to have more than one spouse. The concubines were lower members of the household, and the man had to have the means to provide for them, so mostly richer members of society could afford this. Any child who was born out of a relationship with a concubine, could then be adopted by the married couple.

Women were not allowed to have concubines or other lovers while they were married.

How did this work with same-sex couples? I have no clue. You may have noticed that most history books don't mention them and I don't own many history books to begin with, so you'll just have to do with my best guess, which is that it may have come down to a personal agreement.

If a married man or woman was caught sleeping with anyone who wasn't their spouse (or concubine in the man's case), that was cheating. Cheating was very frowned upon, no matter if it was a man or a woman who did it and it could end in divorce.

Women and men were both allowed to initiate a divorce based on whatever reason, and they could both take their cases to court.

What was the difference between a spouse and a concubine you ask? Their rights.

A spouse had the right to half of the couple's wealth, plus everything they brought into the marriage. They had the right (and obligation) to show up together with their spouse and children in public, because they were considered family. Concubines had no right to any of this. They weren't even considered to be members of the family and the man could always just kick them out of the house without any compensation.

And this is why the king could get several spouses. Because if he marries for a political reason, every single one of his spouses would be considered a full member of the royal family. Keeping a foreign princess as a concubine would be an insult. So the king can have several official spouses, but he is the only one in the country who can. And since in a royal marriage, the king will always be considered the leading member of the couple, he is the one who is allowed to live in polygamy, not the spouse.

Some sources I used for this:

Francois Trassard - La vie des Egyptiens au temps des pharaons (2002.)

Laszlo Kakosy - The history and culture of Ancient Egypt (2005.)

I hope this clears things up ❤️

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading a book about Hatshepsut while reading Exodus honestly is making me see the Moses-in-the-bulrushes episode in a whole new light.

Moses is drawn up out of the water by the pharaoh's daughter. That is significant, not only because it signals her relationship to the pharaoh, but because "King's Daughter" was itself a title that was often bound up with other titles such as...

God's Wife of Amun or God's Wife: This was a title of the highest-ranking priestess of the god Amun. It was generally held by a daughter or wife of the pharaoh. During the 18th dynasty, at least, the title had some political power attached. Even if she were quite young, she could still have held this title.

Great Royal Wife, or King's Wife: The Ancient Egyptians expected the daughters of the pharaoh to marry the next pharaoh. (Eventually, this was no longer required, but if this is the 18th dynasty, this would have been the case.) If she was the Great Royal Wife, she would have been the highest-ranking of the pharaoh's wives.

King's Sister: Marrying the next pharaoh, in theory, meant the King's Daughter had to marry her brother. It also may have been used as a formality even if the pharaoh was more distantly related. While she might not have held this title yet, it would have been in the cards for her in the future.

Additionally, due to polygamy, concubinage, and certain cultural/religious expectations attached to kingship, the pharaoh would likely have had a lot of children already, and a lot of wet nurses as well.

In short, God puts Moses into the hands of the most powerful woman in Egypt, and into a large enough household that he was hidden in plain sight.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, but I cannot help but think about how motherhood is done completely dirty in Crown of Serpents.

Not just by having mother figures with no personality or depth who barely appear in the book to begin with such as Danaë and Cassiopeia, but also through the denying of motherhood by the younger female figures.

Pegasus and Chrysaor are completely erased in this retelling, despite of being her canonical children. Now, since the author obiviously followed the roman version of the myth that means she should've technically remain pregnant after Poseidon raped her. And look, I know that this is an extremely delicate topic, and considering the current state of the world (the US, to be more specific), I'm aware of the fact that having a woman who got raped choosing to keep her children and still loving them to be a quite sensitive scenario that can be easily misinterpreted or criticized. However, that doesn’t mean that the choice of keeping the child itself wasn't that woman's decision, nor that it should be perceived as a threatening to women's bodily autonomy. Are there women who didn't want to raise their rapist's child and eventually got an abortion? Absolutely! But are there also women who chose to keep that child and still loved them? Yes! Feminism is ultimately about giving women choices, and one woman's choice to navigate motherhood despite of the disturbing circumstances under which she remained pregnant doesn't (and shouldn't) dismiss another woman's choice of not wanting that child. In the end life is different for everybody, and you cannot truly challenge your audience by presenting only one side of these type of stories or erasing the nuance of the subject.

Now on Andromeda: In this retelling her original background story is completely changed, so we don't get subjects such as royal incest or child marriage to get explored via her character by default, despite the fact that this is supposed to be a feminist retelling ment to criticize the Patriarchal Society of those times. Now, I can understand to some extent the intention of deleting this type of backstory, for understandable reasons. However, one aspect that still rubs me in a wrong way is her negative perception of motherhood, and the tragedy of discovering that she was ment "not to lead but to breed".

Now, is it true that back then women were expected to get married and have children, and there was certainly a great social pressure on royal women to give birth to a male heir? Of course! But criticizing the expectations people had back then on women and debunking the myth of the ideal or perfect mother is one thing, whereas straight-up demonizing or ridiculizing motherhood is completely another.

In Andromeda's case we're talking here about a woman who had egyptian ancestry via her father. Back in Ancient Egypt love stories were a very common subject in literature, especially during the New Kingdom Era, and the relationships between men and women were usually portrayed as lovely and affectionate. Monogamy was the norm, and after marriage both men and women were usually expected to remain faithful one to another. The major exception was the royal family, where we can see polygamy and incest. Furthermore, there was a great emphasize on sexuality, fertility and the conception of children. Moving to another ancient culture now, in this retelling the author placed Andromeda's home in Joppa and made her a worshipper of Astarte. Ironically though, Astarte was a goddess of love and beauty (similarly with Aphrodite) and personified procreation and fecundity as well. No matter where you place Andromeda's home based on surviving sources you cannot ignore the fact that she was very likely raised and educated in this historical and cultural context, and by extension she would've had a similar opinion on children and motherhood rather than a contemporary one. On the same note I despise the way this retelling implies that the one and only purpose of a royal woman was to give birth, when we know that in Ancient Egypt the queen (Great Royal Wife) occupied different official functions, whereas canaanite women, despite of having less power, still took part in community affairs and possessed influence over politics. Just because we're talking here about Patriarchal Societies that doesn’t mean that we cannot discuss nuances and different perceptions on women's contributions, nor that ancient women were completely powerless or vulnerable (especially when we're reporting to the noble ones).

Having children was the norm and considered something natural and an important step to adulthood and maturity, and the option of remaining unmarried and childless without any sort of constraints appeared very lately historically speaking, being also supported by modern political movements and ideologies. It sounds outdated, I know, but we're talking here about Ancient Greece and projecting a modern mentality on an ancient culture is admittedly wrong since you have to be very aware of limits of these projections.

Now, the author herself said in a note that this retelling makes concious deviations from the historical context in order to adress our modern sensibilities. But my question is: whose modern sensibilities is this retelling adressing? Because if I would take a quess I would say that the way mothers are depicted in this book reflects a western mentality on this topic primarly spread by white women, as well as this generational conflict that is very prominent in the US. It ultimately tickles the sensibilities of a very specific category of women and is rather linked in some sort of a white feminism which only cares about young and childless women instead of going deeper into the different experiences and aspects of womanhood.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why didn't Alexander's policy of marrying into Persian nobility not make him more unpopular in the long run or historical memory, if all the successors rebuked it and Persia reemerged as the enemy of Rome and therefore Byzantium (therefore the Greek lands)?

But all the Successors didn’t. Seleukos quite famously kept his Persian wife, Apama, mother of his heir Antiochus I. And it’s unclear that Ptolemy dumped his either; he may have had up to four wives (not just concubines), including his Persian one, Artakama. Yes, some at once. Royal polygamy.

Also, Alexander’s reputation went up and down in Rome. He was fairly useful from Scipio till Caesar. Then he fell out of fashion under Octavian-Augustus (as he was associated with the East = Cleopatra of Egypt). He came back into vogue later, with Trajan and Hadrian, but also Septimius Severus, and even Commodus. The Romans liked to cast him as either the brash young conqueror or a mad tyrant, depending.

So it’s a little more complicated.

#asks#Alexander's reputation in Rome#Alexander's policy of mixed marriages#Alexander the Great#ancient Persia#ancient Rome#Classics

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read in April

The Death and Life of the Great Lakes by Dan Egan ★★★★★ This nonfiction was compelling and horrifying at the same time. I was aware the Lakes had some issues, but the level of fuckery that has been done to this water by man in the last 150 years is mindblowing. And is still happening, as they are still open to invasive species that affect ecosystems as far away as New Mexico. And yet amazingly, Nature adapts—fish literally evolving their stomachs in less than decades to eat invasive mussels. I feel I need to read more environmental nonfiction like this. Must read if you live in the Great Lakes region, or even if you don't.

I Don't Want to be Understood by Joshua Jennifer Espinoza ★★★★★ I'm not sure how to review poetry so what can I say but beautiful, devastating. The author's poems are both personal and reflective of a more common trans experience like airport security or the anxiety of just walking the dog. Reading this I thought one read-through is just not enough to take these emotions in.

Shubeik Lubeik by Deena Mohamed ★★★★★ (read for Egypt, review linked)

Kaikeyi by Vaishnavi Patel ★★★★★ This novel set in ancient India takes the "evil stepmother" from the Ramayana and retells her story. My previous exposure to the Ramayana is mostly from the animated movie. This book takes a completely different perspective and it is not spoiled if you already know the Ramayana, as characters' hidden motivations and backgrounds are what drives this version. The beginning builds up slowly and at first I was afraid it would be generically feminist, but it became uniquely interesting: a fantasy with a middle-aged mother MC who is also asexual, friendly polygamy (no rival wives), and a thought-provoking take on toxic masculinity from a mother's perspective. It reminds me that I never finished (because my subscription expired) The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni which similarly gives the perspective of a female character, Draupadi from the Mahabharata.

Our Not-so-Lonely Planet Travel Guide by Mone Sorai ★★★★★ I read volumes 1-4 between March and April. Asahi agrees to marry Mitsuki only if he completes a tour of the world with him, so the two men set off on travel adventures together. This was so cute and I am eagerly awaiting my library to get volume 5. I haven't truly read manga in years so it was delightful to see a manga so LGBT-affirming. The couple encounters other queer characters in various countries on their tour (loved the Finnish lesbians XD) who gradually help in-the-closet Asahi with accepting himself. It's also part travel guide with facts, traveler's tips, and intricately illustrated world landmarks.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freud, Moses & Muhammad

Have been reading Moses and Monotheism by Sigmund Freud and he argues that because Judaism shows traces of both the cult of YHWH and Egyptian Atenism, it follows that this happens due to the fusion of a group out of Egypt and a mass of midianite converts at Qadesh. I do not necessarily disagree until when he asserts that there were two Moses.

Egyptian Moses - had the name Moses, instituted circumcision, introduced a strict iconoclastic uncompromising monotheism, intentionally neglected the after life. Was most likely an ambitious governor of Goshen under Akhenaten who fancied himself a candidate to the throne but on being sidelined, left the country peacefully in a time of war with a mass of semitic followers and the Levites (educated egyptian atenists). Angry, Jealous, Decisive and Strict which fits the character of an ambitious nobleman.

Midianite Prophet - Either Jethro or his son in law, Passionate and compromising, A prophet of YHWH who was a volcano god, active at night and slumbering in the day. He introduced the name YHWH as well as a mass of rituals but retained circumcision and the centrality of Moses. However, in return, the egyptian roots had to be done away with and everything from Moses to circumcision were to be given semitic origins.

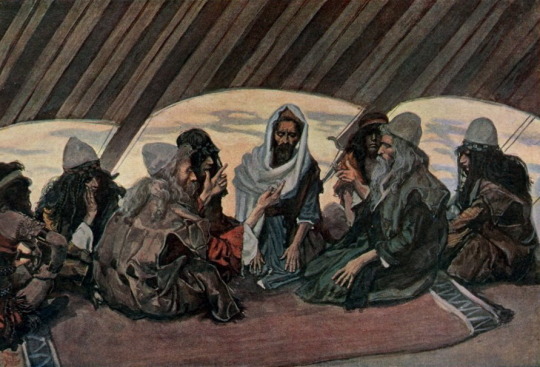

Moses and Jethro by Tissot

This assertion is what I have an issue with and my most basic argument is that Freud might be projecting the originality of modern ideas on to the continuous nature of old world religions. Just because elements found in Atenism and YHWH cults are to be shared with the faith of Moses does not necessitate divorcing him in to two characters or any compromise whatsoever. I will posit the case of Islam (the most recent and final revealed religion) as proof for this with a series of examples which show that Allah does incorporate/allow the continuation of rituals seemingly foreign to Islam (which is an odd assertion as well since both Akhenaten and the Midianites were themselves created by the same god and their thoughts entirely within His grasp)

Allah - a name denoting the One God but had gradually becoming somewhat akin to Elohim and Anu as a passive creator god who had left the rule of His world to Hubal (Baal) and other deities

The Hajj and the Kaabah, once a sanctuary set up by Abraham had long since become the centre of Arabian Polytheism but was restored to Monotheistic worship

Safa and Marwah were idols placed atop two hills that the arabs would run in between but Islam incorporated the practice after destroying the idols and declaring it a re enactment of Hagar running in search of water for Ishmael

Rahman - a name given to the patron god of Yamamah but re purposed for use for The One God

Abraham, Ishmael and Hagar - characters central to both the Judeo Christian world and Arabian mythology were declared proponents of monotheism cleared of their polytheistic baggage

Stoning of adulterers and killing of apostates - retained from Mosaic Law

Fasting on 10th Ashura - re purposing of the Yom Kippur as the Prophet PBUH asserted the muslims have more of a right to the Exodus than the Israelites

Fasting - the Quran explicitly says that it institutes the fasting for muslims just as God has done it for nations before us

A plethora of pre islamic arabian laws were retained in the sharia but modified to be in line with God's plan for example qisas, circumcision, polygamy etc.

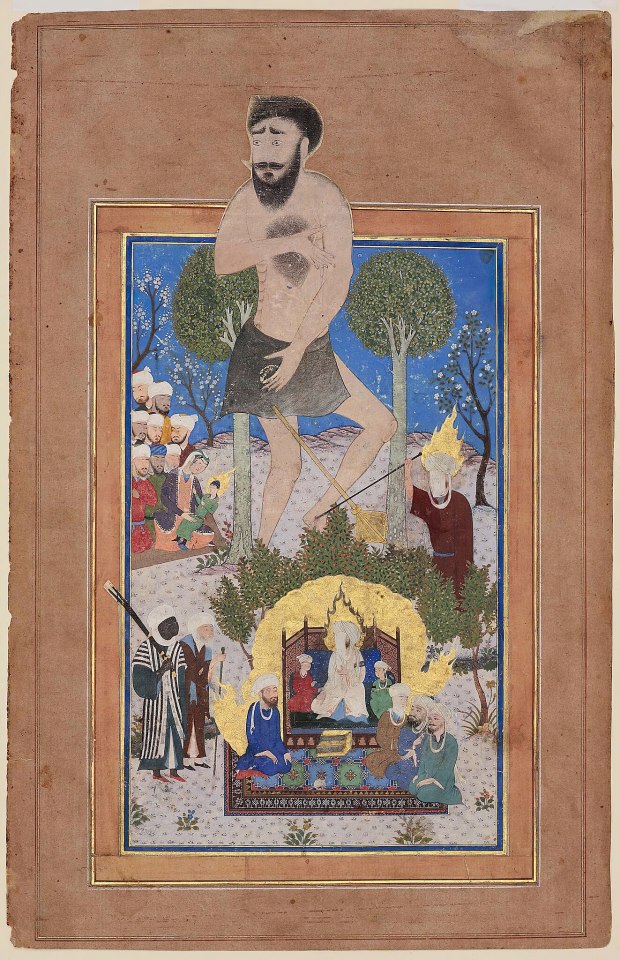

Musa va 'Uj (Top Left: Mary and Jesus, Top Right: Moses battles Og, Bottom: Muhammad with his grandsons and companions)

This is in no way a comprehensive list but I feel it is sufficient to say that Moses' religion "adopting" elements such as the Midianite name for God or Egyptian circumcision or selectively not focusing on the after life in order to separate from their opponents (similar to how Islam has worshippers fold their arms in prayer to distinguish from Jewish prayer or changing the qiblah from Jerusalem to the Kaabah or being discouraged to fast on sabbath etc.). Nor does it reduce God's station and transcendence as it was God Himself in the first place who placed those beliefs and elements in and around His prophets.

God reveals Himself not just in the Book and the Miracle but also in the hissing of a staunch infidel and the uncertain beating of the convert's heart as he latches on to familiar rituals of his ancestors.

#sigmund freud#moses#bible study#quran#islam#prophet muhammad#monotheism#god#christianblr#jewblr#biblestudy#bibleblr#muslimblr#bible#scripture#faith#christian#bible scripture#history#ancient history#ancient egypt#kemetic#allah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 8.29

Holidays

According To Hoyle Day

Arbor Day (Argentina)

Bill & Frank Day

Black Book Clubs Day

Celestial Marriage Day (a.k.a. Polygamy; Mormons)

Clean Your Keyboard Day

Day of Loose Talk

Day of Remembrance of the Defenders of Ukraine (Ukraine)

Fennel Day (French Republic)

Flag Day (Spain)

Galatea Asteroid Day

Gamer’s Day (Mexico, Spain)

Happy Housewives Holiday

Head Day (Iceland)

Hurricane Katrina Anniversary Day (New Orleans)

Individual Rights Day

International Day Against Nuclear Tests (UN)

Judgment Day (in the film “The Terminator”)

Marine Corps Reserve Day

Michael Jackson Day

Miners’ Day (Ukraine)

Municipal Police Day (Poland)

National Caretaker Appreciation Day (Canada)

National College Colors Day

National Day of Lesbian Visibility (Brazil)

National Monterey County Fair Day

National Police’s Day (Poland)

National Sarcoidosis Awareness Day

National Sport Sampling Day

National Sports Day (India)

Nut Spas (Russia)

Potteries Bottle Oven Day (UK)

Targeted Individual Day

Telugu Language Day (India)

World Day of Video Games

Zipper Clasp Locker Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Chop Suey Day

Gnocchi Day (Argentina)

International Peppercorn Day

Lemon Juice Day

More Herbs, Less Salt Day

National Swiss Winegrowers Day

Independence & Related Days

Hjalvik (Declared; 2020) [unrecognized]

Mivland (Declared; 2018) [unrecognized]

Popular Consultation Anniversary Day (East Timor)

Slovak National Uprising Anniversary Day (Slovakia)

Veyshnoria (Declared; 2017) [unrecognized]

New Year’s Days

First Day of Thoth (Ancient Egypt)

5th & Last Thursday in August

Cabernet Day [Thursday before Labor Day]

Daffodil Day (Australia) [Last Thursday]

National Banana Pudding Day [Last Thursday]

National Cabernet Sauvignon Day [Last Thursday]

Thirsty Thursday [Every Thursday]

Thoughtful Thursday [Thursday of Be Kind to Humankind Week]

Three-Bean Thursday [Last Thursday of Each Month]

Three for Thursday [Every Thursday]

Thrift Store Thursday [Every Thursday]

Throw Away Thursday [Last Thursday of Each Month]

Throwback Thursday [Every Thursday]

Weekly Holidays beginning August 29 (4th Full Week of August)

National Sweet Corn Week (thru 9.2)

Festivals Beginning August 29, 2024

The Blue Hill Fair (Blue Hill, Maine) [thru 9.2]

Chicago Jazz Festival (Chicago, Illinois) [thru 9.1]

Dragon Con (Atlanta, Georgia) [thru 9.2]

Epcot International Food & Wine Festival (Lake Buena Vista, Florida) [thru 11.23]

Gatineau Hot Air Balloon Festival (Gatineau, Canada) [thru 9.2]

Hopkinton State Fair (Contoocook, New Hampshire) [thru 9.2]

Kamiah BBQ Days (Kamiah, Idaho) [thru 8.31]

Key West BrewFest (Key West, Florida) [thru 9.2]

Lindisfarne Festival (Berwick-upon-Tweed, United Kingdom) [thru 9.1]

Louisiana Shrimp & Petroleum Festival (Morgan City, Louisiana) [thru 9.2]

National Championship Chuckwagon Races (Clinton, Arkansas) [thru 9.1]

Peach Days (Hurricane City, Utah) [thru 8.31]

Rocklahoma (Pryor, Oklahoma) [thru 9.1]

Taste to Remember (Dublin, Ohio)

Volksfeest and Bloemencorso Winterswijk (Winterswijk, Netherlands) [thr 9.1]

Feast Days

Adelphus of Metz (Christian; Saint)

Beheading of St. John the Baptist (Christian)

Blobfish Day (Pastafarian)

Day of Loose Talk (Shamanism)

Dr. Lily Rosenbloom (Muppetism)

Eadwold of Cerne (Christian; Saint)

Euphrasia Eluvathingal (Syro-Malabar Catholic Church)

Feast of Agios Ioannis (Halki, Hittitie God of Grain)

First Day of Thoth (Egyptian New Year)

Gahan Wilson Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Gelede (Mask-Wearing Ritual; Yoruba People of Nigeria)

The Great Visitation to Guaire (Celtic Book of Days)

Hajime Isayama (Artology)

Hathor’s Day (Pagan)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (Artology)

John Bunyan (Episcopal Church)

John Leech (Artology)

Maurice Maeterlinck (Writerism)

Medericus (a.k.a. St. Merry; Christian; Saint)

Midnight Muffins Day (Starza Pagan Book of Days)

Nativity of Hathor (Egyptian Goddess of Joy & Drunkenness)

Oliver Wendell Holmes (Writerism)

Papin (Positivist; Saint)

Pardon of the Sea (Festival to Ahes, Pagan Goddess of the Sea; Brittany; Everyday Wicca)

René Depestre (Writerism)

Sabina (Christian; Martyr)

Sebbi (a.k.a. Sebba), King of Essex (Christian; Saint)

Sorel Etrog (Artology)

Thiruvonam (Rice Harvest Festival, Day 2; Kerala, India)

Thom Gunn (Writerism)

Vitalis, Sator and Repositus (Christian; Saints)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 241 [53 of 72]

Sakimake (先負 Japan) [Bad luck in the morning, good luck in the afternoon.]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [38 of 60]

Urda (The Oldest Fate)

Premieres

At Your Service Madame (WB MM Cartoon; 1936)

Balls of Fury (Film; 2007)

Butcher's Crossing, by John Williams (Novel; 1960)

Cat-Tails for Two (WB MM Cartoon; 1953)

A Date for Dinner (Mighty Mouse Cartoon; 1947)

Definitely Maybe, by Oasis (Album; 1994)

The Early Bird Dood It! (Tex Avery MGM Cartoon; 1942)

4’33”, by John Cage (Modernist Composition; 1952)

The Fugitive final episode (Most Watched TV Show; 1967)

The Full Monty (Film; 1987)

Here Today, Gone Tamale (WB LT Cartoon; 1959)

Independent Women, by Destiny’s Child (Song; 2000)

It’s A Pity To Say Goodnight, recorded by Ella Fitzgerald (Song; 1946)

Kid Galahad (Elvis Presley Film; 1962)

Mary Poppins (Film; 1964)

Movie Mad (Ub Iwerks MGM Cartoon; 1931)

Move It, by Cliff Richard and the Drifters (Song; 1958)

One of Our States Is Missing (Super Chicken Cartoon; 1967) [#2]

Popalong Popeye (Fleischer/Famous Popeye Cartoon; 1952)

Pretty Woman, by Roy Orbison (Song; 1964)

Ridiculousness (TV Series; 2011)

Runaway, by Janet Jackson (Song; 1995)

Saint Errant, by Leslie Charteris (Short Stories 1948) [Saint #29]

Shanghai Surprise (Film; 1986)

Signing Off, by UB40 (Album; 1980)

The Skeleton Dance (Ub Iwerks Silly Symphony Disney Cartoon; 1929) [1st SS]

Twinkletoes in Hat Stuff (Animated Antics Cartoon; 1941)

Today’s Name Days

Beatrix, Johannes, Sabine (Austria)

Anastas, Anastasi, Anastasiya (Bulgaria)

Bazila, Ivan, Sabina, Sebo, Verona (Croatia)

Evelína (Czech Republic)

Johannes (Denmark)

Õnne, Õnnela (Estonia)

Iina, Iines, Inari, Inna (Finland)

Médéric, Sabine (France)

Beatrice, Johannes, Sabine (Germany)

Arkadios (Greece)

Beatrix, Erna (Hungary)

Battista, Giovanni, Sabina (Italy)

Aiga, Aigars, Armīns, Vismants (Latvia)

Barvydas, Beatričė, Gaudvydė, Sabina (Lithuania)

Jo, Johan, Jone (Norway)

Flora, Jan, Racibor, Sabina (Poland)

Nikola (Slovakia)

Juan (Spain)

Hampus, Hans (Sweden)

Candace, Candice, Poppy, Sabina, Sabra, Sabrina (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 242 of 2024; 124 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 4 of Week 35 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Coll (Hazel) [Day 27 of 28]

Chinese: Month 7 (Ren-Shen), Day 26 (Yi-Chou)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 25 Av 5784

Islamic: 23 Safar 1446

J Cal: 2 Gold; Oneday [1 of 30]

Julian: 16 August 2024

Moon: 18%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 18 Gutenberg (9th Month) [Black]

Runic Half Month: Rad (Motion) [Day 7 of 15]

Season: Summer (Day 71 of 94)

Week: 4th Full Week of August

Zodiac: Virgo (Day 8 of 32)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

song of the day : aug 28

Pyramids by Frank Ocean - channel ORANGE

this song is meant torepresents the affects of slavery, sexism, and the tremendous change in treatment of said minority groups throughout the history of time

from minutes 0:00 - 3:53, Frank is setting us in 50BC, around 2000 years ago, during Cleopatras reign over Ancient Egypt, as assumed through the repetition of “Our Queen” and “Cleopatra”. This is a story of The singers unrequited love affair with Queen Cleopatra .The singer is supposedly one of Cleopatra many lovers, however the singer is blind sighted and denied her unfaithfulness. He assumed her absence equates to her kidnapping, going as far as “setting the cheetahs on the loose” which can also be a double meaning for a “cheater”. The second verse of the first half is meant to describe how royal Egyptians lived and their treatment, they, Cleopatra in specific, is a diamond in a rocky world, her skins is a beautiful shade of bronze, and her hair is a rich cashmere shade. This is also a recollection on the singers part of meeting his queen, and how it felt for him. their bodies “march to the rhythm” and noise fills up the grand pyramids. Now, in our third verse, the singer has realized that his love was not taken from him, but chose to leave. Where was was once the “Jewel of Africa” she is has “lost her value” and is no longer “precious”. The singer catches Cleopatra sleeping with a man, ‘Samson’. The singer seems to hold Samson in a higher light, claiming jealousy of his “full head of hair”. However, everything takes a turn after a ‘serpent’ has killed Cleopatra. Frank choose very wisely to say “He” after the servant struck the Queen of Egypt. He does this to show that Cleopatras desperation for more attention got her killed. The man who she cheated on the singer with killed her, putting an abrupt end on the Queen life and legacy.

As we enter a beautiful musical interlude, the notes presented create a perfect music pyramid, going up by half steps and back down the scale repeatedly.

This transitions us to the second half of our song, 3:54- end. We are now in current times. Although it’s unclear where geographically the time is set, I’d like to think he sets these verses in Las Vegas, Nevada, he and cleopatra “hit the strip”, the term used when describing Las Vegas Blvd. Now our story starts in a dingy motel room instead of a glorious pyramids of Egypt. The singer, having to have once been powerful enough to work his way into the pyramids, is now a street pimp prostituting girls. And Cleopatra, our famed and beloved Queen of Egypt, is a prostitute selling her body for the attention she once never needed to captivate. Cleopatra and the singer are in this motel room together, mostly likely after a one night stand or hook-up. Cleopatra leaves this one night stand to go “work at the pyramids”, but interestingly enough, the singer reveals that Cleopatra works for him, as implied in the line “got your girl working for me” and “hit the strip and my bills paid.” She is a prostitute, he is her pimp. Their relationship is similar to that of their previous lives. Cleopatra is a woman of polygamy, she is never set on one man, and the singer wants her loyalties. However, In this time line, the singer is not naive and knows of Cleopatras other endeavors, but he implies disparity over this since he knows she doesn’t truly love him; “But you’re love ain’t free, no.” The only time Cleopatra will ever “love” him is in a paid, intimate setting.

Overall, this 10 minute song shows the flow of time and how the centuries changes humans. Where Cleopatra was once a furious Queen who was highly respected and influential, she is now nothing more than a street prostitute, living in and out of motels which were once grand pyramids. The singer continues a life of unrequited love throughout his different lives, and how Cleopatra will never change.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m so scared for the girls and women of Gambia right now, Muslim scrotes continue to prove themselves to be the worst, if you didn’t know their government are working to over turn their ban on FGM believing that banning it means that they can’t fully practice their religion (Islam) and since a big majority of the population is muslim they want to change the law so girls can be mutilated for men.

Fair enough anon, FGM is not the fault of Islam. It's an ancestral practice that tracks as back as to pharaonic Egypt - so waaay before Islam was a thing. Even today, FGM is highly practized in Egypt, even in the Christian copt community. So this tradition clearly transcends religions.

If FGM was an islamic tradition, it would be widespread on the whole Islamic zone, but FGM is mainly in Africa - not really a thing in middle east. So yeah it's an African thing. (Hotep can stay mad lol)

It's so funny to see Hotep seethe about it and blame arabs for importing the practice into Africa lol. Hotep are delulu weirdos fantasizing about an ancestral Africa, glorify & myth-ify the continent's past to a ridiculous extent, and refuse to be remotely critical of our traditions (they constantly complain about the white man erasing our "tradition" while never questioning whether said traditions where good or not - sorry but I'm grateful for Christianity for calling out (blood) ritual sacrifices and witchcraft 🤷🏾♀️)

So when we explain to them that FGM is *from* Africa (Egypt) they freak out. Which is weird because they usually LOOOOOVE claiming Egypt and how pharaohs were Black.... but suddenly they refuse to claim this Egyptian tradition 👀

THAT BEING SAID I'm absolutely not surprised to see FGM being upheld mostly in Muslim African countries. Male will always find ways to abuse and oppress women. Especially Muslim men. As much as I said that FGM transcends religions, I'm not surprised to see it's Muslim men fighting to get it unbanned.

I'm glad I'm from a heavily Christian country (Republic of Congo) and that we uphold the Christian value of respecting one's body integrity. We still struggle with polygamy but Glory to God it's getting more and more uncommon. Thank you Jesus for monogamy 💜

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on polygamy and open relationships?

I once read a beautiful article, in English of course, about someone exploring polygamy for the first time, and telling the story about how the biggest two reasons that makes it too hard for people are 1) peer pressure, and 2) the belief that it's our partner's job to manage our insecurities. She wept the first time her boyfriend slept with someone else, cause she couldn't help but to compare herself to the other girl, and feeling like she's losing him to her. But then she kept thinking that it's all really about her, not him. He's not cheating. They agreed on it. And it sucks for her, but it's her job to know which parts of her were bothered, and why, and how can she get her feelings aligned with her belief in polygamy. It was a wild ride, it required her to make peace with her body, her self worth, her co dependency, and her old notions about monogamy being the only valid form of relationships. Long story short, I think polygamy is valid for those who can handle it, but I personally don't think it's for me. I wouldn't be able to joggle more than one partner, and I'd struggle too much with my insecurities. And god oh god I can't even think of how can people pull it off in Egypt, unless they make sure they live in their own bubble.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The topic of a man secretly marrying another woman without the knowledge or consent of his first wife is a controversial and sensitive issue that raises many ethical, legal, and religious questions.

**Legal Perspective:**

In many countries, including those with Islamic law, polygamy (the practice of having multiple spouses) is legal, but with certain conditions. For example, in Egypt, polygamy is legal, but the man must obtain the permission of his first wife before marrying another woman. In other countries, such as Tunisia and Morocco, polygamy is banned.

**Religious Perspective:**

In Islam, polygamy is allowed, but with certain restrictions. The Quran permits a man to marry up to four wives, provided he can treat them all justly and fairly (Quran 4:3). However, many Islamic scholars and interpreters argue that polygamy is only allowed in exceptional circumstances, such as when a man's first wife is unable to bear children or is unable to fulfill her marital duties.

**Ethical Perspective:**

Secretly marrying another woman without the knowledge or consent of one's first wife is widely considered to be a form of deception and betrayal. It can cause significant emotional harm to the first wife, who may feel deceived, betrayed, and humiliated. This behavior can also damage the trust and intimacy in the first marriage, potentially leading to its breakdown.

**Arguments For and Against:**

**Arguments For:**

1. **Religious freedom:** Some argue that a man's right to practice his religion, including polygamy, should be respected.

2. **Personal choice:** Others argue that a man's decision to marry another woman is a personal choice that should not be judged or restricted.

**Arguments Against:**

1. **Deception and betrayal:** Secretly marrying another woman without the knowledge or consent of one's first wife is a form of deception and betrayal.

2. **Emotional harm:** This behavior can cause significant emotional harm to the first wife, including feelings of sadness, anger, and betrayal.

3. **Lack of transparency:** Secretly marrying another woman lacks transparency and honesty, which are essential values in any healthy relationship.

**Conclusion:**

While polygamy is allowed in some legal and religious contexts, secretly marrying another woman without the knowledge or consent of one's first wife is widely considered to be a form of deception and betrayal. It can cause significant emotional harm to the first wife and damage the trust and intimacy in the first marriage. Therefore, it is essential to approach this issue with sensitivity, respect, and transparency, prioritizing open communication and mutual understanding in all marital relationships.

0 notes

Text

Holidays 8.29

Holidays

According To Hoyle Day

Arbor Day (Argentina)

Bill & Frank Day

Black Book Clubs Day

Celestial Marriage Day (a.k.a. Polygamy; Mormons)

Clean Your Keyboard Day

Day of Loose Talk

Day of Remembrance of the Defenders of Ukraine (Ukraine)

Fennel Day (French Republic)

Flag Day (Spain)

Galatea Asteroid Day

Gamer’s Day (Mexico, Spain)

Happy Housewives Holiday

Head Day (Iceland)

Hurricane Katrina Anniversary Day (New Orleans)

Individual Rights Day

International Day Against Nuclear Tests (UN)

Judgment Day (in the film “The Terminator”)

Marine Corps Reserve Day

Michael Jackson Day

Miners’ Day (Ukraine)

Municipal Police Day (Poland)

National Caretaker Appreciation Day (Canada)

National College Colors Day

National Day of Lesbian Visibility (Brazil)

National Monterey County Fair Day

National Police’s Day (Poland)

National Sarcoidosis Awareness Day

National Sport Sampling Day

National Sports Day (India)

Nut Spas (Russia)

Potteries Bottle Oven Day (UK)

Targeted Individual Day

Telugu Language Day (India)

World Day of Video Games

Zipper Clasp Locker Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Chop Suey Day

Gnocchi Day (Argentina)

International Peppercorn Day

Lemon Juice Day

More Herbs, Less Salt Day

National Swiss Winegrowers Day

Independence & Related Days

Hjalvik (Declared; 2020) [unrecognized]

Mivland (Declared; 2018) [unrecognized]

Popular Consultation Anniversary Day (East Timor)

Slovak National Uprising Anniversary Day (Slovakia)

Veyshnoria (Declared; 2017) [unrecognized]

New Year’s Days

First Day of Thoth (Ancient Egypt)

5th & Last Thursday in August

Cabernet Day [Thursday before Labor Day]

Daffodil Day (Australia) [Last Thursday]

National Banana Pudding Day [Last Thursday]

National Cabernet Sauvignon Day [Last Thursday]

Thirsty Thursday [Every Thursday]

Thoughtful Thursday [Thursday of Be Kind to Humankind Week]

Three-Bean Thursday [Last Thursday of Each Month]

Three for Thursday [Every Thursday]

Thrift Store Thursday [Every Thursday]

Throw Away Thursday [Last Thursday of Each Month]

Throwback Thursday [Every Thursday]

Weekly Holidays beginning August 29 (4th Full Week of August)

National Sweet Corn Week (thru 9.2)

Festivals Beginning August 29, 2024

The Blue Hill Fair (Blue Hill, Maine) [thru 9.2]

Chicago Jazz Festival (Chicago, Illinois) [thru 9.1]

Dragon Con (Atlanta, Georgia) [thru 9.2]

Epcot International Food & Wine Festival (Lake Buena Vista, Florida) [thru 11.23]

Gatineau Hot Air Balloon Festival (Gatineau, Canada) [thru 9.2]

Hopkinton State Fair (Contoocook, New Hampshire) [thru 9.2]

Kamiah BBQ Days (Kamiah, Idaho) [thru 8.31]

Key West BrewFest (Key West, Florida) [thru 9.2]

Lindisfarne Festival (Berwick-upon-Tweed, United Kingdom) [thru 9.1]

Louisiana Shrimp & Petroleum Festival (Morgan City, Louisiana) [thru 9.2]

National Championship Chuckwagon Races (Clinton, Arkansas) [thru 9.1]

Peach Days (Hurricane City, Utah) [thru 8.31]

Rocklahoma (Pryor, Oklahoma) [thru 9.1]

Taste to Remember (Dublin, Ohio)

Volksfeest and Bloemencorso Winterswijk (Winterswijk, Netherlands) [thr 9.1]

Feast Days

Adelphus of Metz (Christian; Saint)

Beheading of St. John the Baptist (Christian)

Blobfish Day (Pastafarian)

Day of Loose Talk (Shamanism)

Dr. Lily Rosenbloom (Muppetism)

Eadwold of Cerne (Christian; Saint)

Euphrasia Eluvathingal (Syro-Malabar Catholic Church)

Feast of Agios Ioannis (Halki, Hittitie God of Grain)

First Day of Thoth (Egyptian New Year)

Gahan Wilson Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Gelede (Mask-Wearing Ritual; Yoruba People of Nigeria)

The Great Visitation to Guaire (Celtic Book of Days)

Hajime Isayama (Artology)

Hathor’s Day (Pagan)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (Artology)

John Bunyan (Episcopal Church)

John Leech (Artology)

Maurice Maeterlinck (Writerism)

Medericus (a.k.a. St. Merry; Christian; Saint)

Midnight Muffins Day (Starza Pagan Book of Days)

Nativity of Hathor (Egyptian Goddess of Joy & Drunkenness)

Oliver Wendell Holmes (Writerism)

Papin (Positivist; Saint)

Pardon of the Sea (Festival to Ahes, Pagan Goddess of the Sea; Brittany; Everyday Wicca)

René Depestre (Writerism)

Sabina (Christian; Martyr)

Sebbi (a.k.a. Sebba), King of Essex (Christian; Saint)

Sorel Etrog (Artology)

Thiruvonam (Rice Harvest Festival, Day 2; Kerala, India)

Thom Gunn (Writerism)

Vitalis, Sator and Repositus (Christian; Saints)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 241 [53 of 72]

Sakimake (先負 Japan) [Bad luck in the morning, good luck in the afternoon.]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [38 of 60]

Urda (The Oldest Fate)

Premieres

At Your Service Madame (WB MM Cartoon; 1936)

Balls of Fury (Film; 2007)

Butcher's Crossing, by John Williams (Novel; 1960)

Cat-Tails for Two (WB MM Cartoon; 1953)

A Date for Dinner (Mighty Mouse Cartoon; 1947)

Definitely Maybe, by Oasis (Album; 1994)

The Early Bird Dood It! (Tex Avery MGM Cartoon; 1942)

4’33”, by John Cage (Modernist Composition; 1952)

The Fugitive final episode (Most Watched TV Show; 1967)

The Full Monty (Film; 1987)

Here Today, Gone Tamale (WB LT Cartoon; 1959)

Independent Women, by Destiny’s Child (Song; 2000)

It’s A Pity To Say Goodnight, recorded by Ella Fitzgerald (Song; 1946)

Kid Galahad (Elvis Presley Film; 1962)

Mary Poppins (Film; 1964)

Movie Mad (Ub Iwerks MGM Cartoon; 1931)

Move It, by Cliff Richard and the Drifters (Song; 1958)

One of Our States Is Missing (Super Chicken Cartoon; 1967) [#2]

Popalong Popeye (Fleischer/Famous Popeye Cartoon; 1952)

Pretty Woman, by Roy Orbison (Song; 1964)

Ridiculousness (TV Series; 2011)

Runaway, by Janet Jackson (Song; 1995)

Saint Errant, by Leslie Charteris (Short Stories 1948) [Saint #29]

Shanghai Surprise (Film; 1986)

Signing Off, by UB40 (Album; 1980)

The Skeleton Dance (Ub Iwerks Silly Symphony Disney Cartoon; 1929) [1st SS]

Twinkletoes in Hat Stuff (Animated Antics Cartoon; 1941)

Today’s Name Days

Beatrix, Johannes, Sabine (Austria)

Anastas, Anastasi, Anastasiya (Bulgaria)

Bazila, Ivan, Sabina, Sebo, Verona (Croatia)

Evelína (Czech Republic)

Johannes (Denmark)

Õnne, Õnnela (Estonia)

Iina, Iines, Inari, Inna (Finland)

Médéric, Sabine (France)

Beatrice, Johannes, Sabine (Germany)

Arkadios (Greece)

Beatrix, Erna (Hungary)

Battista, Giovanni, Sabina (Italy)

Aiga, Aigars, Armīns, Vismants (Latvia)

Barvydas, Beatričė, Gaudvydė, Sabina (Lithuania)

Jo, Johan, Jone (Norway)

Flora, Jan, Racibor, Sabina (Poland)

Nikola (Slovakia)

Juan (Spain)

Hampus, Hans (Sweden)

Candace, Candice, Poppy, Sabina, Sabra, Sabrina (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 242 of 2024; 124 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 4 of Week 35 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Coll (Hazel) [Day 27 of 28]

Chinese: Month 7 (Ren-Shen), Day 26 (Yi-Chou)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 25 Av 5784

Islamic: 23 Safar 1446

J Cal: 2 Gold; Oneday [1 of 30]

Julian: 16 August 2024

Moon: 18%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 18 Gutenberg (9th Month) [Black]

Runic Half Month: Rad (Motion) [Day 7 of 15]

Season: Summer (Day 71 of 94)

Week: 4th Full Week of August

Zodiac: Virgo (Day 8 of 32)

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

WHAT IS MARRIAGE AND TYPES OF MARRIAGE

Marriage is a socially approved relationship between a man and a woman that binds them in a permanent relationship. Which not only binds them physically but mentally and emotionally too. Marriage is a social institution that helps you to fulfill the needs of a man and woman physically, mentally, culturally, and economically. According to spirituality, it is a social duty that helps to form a society.

We all know that humans are social animals who need someone's love, care, and support. The era of the beginning of this world. In every civilization, we noticed that everyone wants support.

Hunter-gatherer time(ancient time)-

There is some evidence that we noticed that individual in this society wants love, care, and support. Opposites attract each other and form a family and a society. However, these relationships mainly based on love rather than ritual practices.

Ancient Civilization Marriage -

As civilization developed, they performed more structured forms of marriage. Their marriage was mainly recorded on clay tablets. They also explain the rights and responsibilities of each partner. During Ancient times, polygamy and polyandry were performed. In Egypt, marriage was often a legal contract and the ceremonies were conducted to symbolize the union.

Greco-Roman Influence-

During Greece and Rome, marriage was performed in both religious and legal dimensions. The Romans, in particular, formalized the legal aspects of marriage, and Roman law greatly influenced the development of marriage customs in Western cultures. They perform the marriage and form a family.

Religious Influence-

With the rise of diversity of religions like Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. Marriage became increasingly associated with religious ceremonies. These religions often played a central role in defining the moral and social aspects of marriage. Different religion performs their rituals for marriage.

Medieval Europe

In medieval Europe, the Catholic Church played a significant role in regulating and formalizing marriages. They form marriage in the church The marriage was considered a physical and emotional bond, and the church had authority over the laws.

Renaissance and Reformation-

During the Renaissance, there was a shift in attitudes toward marriage. The people had the right to choose whom they love, care and feel romantic

18th and 19th Centuries-

The concept of marriage continued to evolve and form an evolution in society. The idea of companionate marriage, based on love and emotional connection, gained prominence. However, social and economic factors continued to influence marital unions.

20th Century-

There were significant changes in marriage patterns, influenced by social, economic, and cultural shifts. The women's movements were also started because of several wrong activities like sati practice, girls' child marriage, domestic violence for dowry, etc.

Contemporary Times-

Now during contemporary times, there are diverse types of rituals that are practiced to perform marriages. There are different types of marriage in modern times like-

Exogamy- In this the people outside the community marry each other.

Endogamy- The custom of the Same community marriage.

Love marriage- In which both man and woman love each other before the marriage.

Arrange marriage- In which the family and society help to choose your life partner.

Now, People also perform same-sex marriage in society. This also occurs because of some hormonal problem in which an individual loves the same gender. Our society has also named it LGBTQ+.

It's important to note that the history of marriage is complex and multifaceted, and the institution has been shaped by a variety of cultural, religious, and social factors over millennia. Different cultures and societies have their unique traditions and customs surrounding marriage.

0 notes

Text

The History of Feminism in Egypt

Egyptian Feminism emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a part of many other political conversations happening at the time. These included tensions between islamic modernism and traditional islamic ideologies

Islamic modernism served as a catalyst for feminist consciousness. In this fight for Islamic reform, feminist writing gradually developed. There were arguments for gender reform issues like veiling, seclusion, divorce and polygamy.

The first feminist movements were first expressed by upper and middle class women in Egypt. They advocated for more female roles in the workplace, women’s education, challenged domestic labor and advocated for unveiling.

Women’s rights were further proliferated after Egypt won independence from Britain in 1922 with the help of various women’s organizations. In 1924, Egypt became the first Islamic country to de-veil women without government intervention. The Egyptian feminist party was founded in 1923 and the Egyptians Women’s political party was established in 1942 with the objective to fight for gender equality.

The feminist agenda in Egypt has been regenerated by recent Islamic attacks on women’s rights.

0 notes

Text

The Emergence of the Modern Coptic Papacy - A Review

In this work, Magdi Guirguis and Nelly Van Doorn-Harder present us with one of the first scholarly works on the modern Egyptian Church in English. This volume details the history of the Coptic Church from the Ottoman era (1517-1798) to the modern day through the lives of its patriarchs. In this review, we will be paying particular attention to the conflict between the Coptic popes and the Coptic lay notables (arakhina) in their struggle for hegemony over the wider Coptic Church and community.

Before we begin our review, it is worth mentioning the historical documents used by Magdi Guirguis, who authored part one of the book, titled: The Coptic Papacy under Ottoman Rule. These sources included:

1. Records of the shari’a courts found in Dar al-Watha’iq al-Qawmiya in Cairo; these document aspects of everyday life in Egypt from the 16th to 19th centuries.

2. Diwan al-Ruznama records, also found in Dar al-Watha’iq al-Qawmiya in Cairo; these provide a record of the history of the monasteries, their restoration and destruction dates, as well as their financial endowments by the state

3. Archives of the Coptic Orthodox patriarchate in Cairo

Guirguis’ meticulousness in his research is impressive, and he successfully sheds light on what many historians consider to be a very stagnant and impenetrable period in Egyptian history.

When talking about the relations between the Copts and the Ottoman state, it is important to contextualize this relationship in light of the ‘aqd al-dhimma (or “covenant of protection”), which had been in place since the time of the Caliphate of Umar in the 7th century. This “fundamental legal reference point” (as the author calls it) basically rendered the Copts second-class citizens in their own country and in the eyes of the Islamic state. Throughout the Coptic community’s time under their Islamic hegemons, the authority of the Coptic patriarch would fluctuate. The extent of his power would vary depending on the whims of the state. At times, the Islamic government would support the patriarch and would enact measures to ensure his absolute control over his church. At other times, the state would seek to limit his authority, sometimes even siding with the Coptic laity over their own pope. This is a recurring theme throughout this period of Coptic Church history: with both lay elites and the patriarch vying for power over the Coptic community. To tease this theme out, we will discuss some interesting events during the reigns of popes John XIII, John XIV, and Mathew III.��

During the tenure of John XIII, the Coptic patriarch enjoyed extensive jurisdiction over souls as far as Ethiopia, Nubia, and even Jerusalem. The Coptic Church also lost several crucial dioceses during this time, including the Pentapolis, Rhodes, and Cyprus. During his time in office the patriarch was solely responsible for collecting the jizya and representing the Coptic community before the state. John XIII took it upon himself to battle changing sexual mores. Many Copts and Muslims alike during this period were practicing polygamy, concubinage, and even prostitution. John XIII showed no hesitation in wielding his religious authority to combat this moral threat festering in his community. This patriarch would enact excommunications and urge the wider community to ostracize those who engaged in deviant behaviors. Primary source documents show that this campaign was an overwhelming success.

Under John XIV and Gabriel VIII, the Coptic Church came very close to union with Rome. In response to the Turkish threat and the Protestant revolt, the Roman Church undertook efforts to unite all of Christendom. We know that the reigning Coptic patriarch during the council of Ferrara-Florence sent representatives to the council and that a bull of union with the Copts was issued by Eugene IV of Rome. The rapprochement efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful, however. Nevertheless, reconciliation attempts with the Coptic Church continued well into the 16th century. John XIV (1571-85) warmly welcomed a Roman delegation to Cairo to discuss the reestablishment of communion between the two sees. Pope John and most of his bishops were initially onboard, but many ultimately defected from the reunion agreement. John XIV died before being able to unilaterally sign a declaration of union with the Roman Church.

John XIV’s successor, Gabriel VIII, is said to have signed a reunion agreement with Rome in January 1597. Gabriel is even said to have implemented the Gregorian calendar into the liturgical cycle of the Egyptian Church. This caused quite an uproar amongst the Coptic laity who opened a case against their patriarch with the Muslim judge in Cairo. The Islamic jurist ruled against the patriarch and in favor of the Coptic gentry. According to the ruling, the Coptic pope had no right to change the church calendar and that it was a violation of Shar’ia for him to force the Coptic faithful to follow the newly implemented calendar. In another incident, the patriarch tried to implement a new way of calculating the date of easter. The Coptic gentry again appealed to a Shar’ia court, this time in Alexandria. The jurists deemed the new calculation inaccurate and ruled that the patriarch had to follow the calculation of the Muslim astronomers. Despite these tensions, reunion efforts with Rome would continue until the mid-18th century, when a Coptic bishop by the name of Antonious of Jirja converted to Catholicism.

Gabriel VIII’s successor, Mark V, suffered a tempestuous papacy. Mark raised the ire of many of the Coptic gentry for his opposition to polygamy. The Coptic laity, with the support of the bishop of Damietta, lodged a complaint against their patriarch to the Islamic authorities. Mark was deposed and an anti-pope John née Girgis Ibn Butrus was installed in his place. Mark V was eventually reinstated after the reign of the then Pasha ended in August 1611. This episode in ecclesiastical history highlights the lengths the Coptic elites were willing to secure their polygamous and polyamorous practices. We even have a story of one Coptic patriarch, John XV, being poisoned by a Coptic archon after the former rebuked him for practicing concubinage.

About halfway through the 17th century, control over the Coptic community shifted from the patriarch and bishops to the Coptic notables or arakhina. This came at a time where the state institutions of the Ottoman empire were beginning to weaken, and power began to decentralize to various local authorities. Thus, in transferring power from her patriarch to the Coptic lay notables, it can be said that Coptic Church at this time acted as a microcosm of the wider Ottoman empire. This transfer of power eventually reached a point where the notables would appoint both the Coptic patriarch as well archbishops for jurisdictions as far as Ethiopia. The head of the arakhina was appointed by the wider community, and followed a very clear and traceable line of succession.

The Coptic archon class maintained good relations with state authorities, Islamic religious leaders, and became the primary patrons of the Coptic clergy and faithful. So extensive was the power of this elite lay class, that the hierarchy often had to turn a blind eye to polygamy and concubinage so as to avoid clashing with them. By far the most remarkable Coptic archon of this period is Mu’allam Ibrahim El Gawhiri, who rose to become Egypt’s chief scribe during the latter half of the 18th century. His statesmanship and high ethics were praised even by the Islamic historian Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti. Mu’allam Ibrahim’s brother Girgis assumed the former’s duties upon his passing. The brothers are generally considered the last of the Coptic archons to exercise strong leadership over the community. As Egypt moved into the 19th century, the control of the Coptic Church shifted from the gentry back to the hierarchy.

For the remainder of this review, we will discuss the patriarchs who can rightly be described as the architects of the modern Coptic Orthodox Church. Following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, massive transformations in law, administration, trade, and education ensued. In the wake of this great change, arose those whom Nelly van Doorn-Harder calls the “great reformers” of the contemporary Coptic Church. These include: Cyril IV (1854-1861), Cyril VI (1959-1971), and Shenouda III (1971-2012).

Cyril IV pushed for Coptic participation in the army and government. He also enacted many educational reforms, in an age where many Copts were still captivated by magic and superstition. Clergy were often ignorant and had to sell their religious services to make ends meet. To combat this, Cyril IV provided salaries for priests, summoned them to weekly meetings to engage in theological reading and discussion, and imported a printing press from Austria which he used to print and distribute books to local parishes free of charge. He also opened a school called Madrasat al-Aqbat al-Kubra which drew Muslims and Copts alike, as well as the first Egyptian school for girls. During his ecclesiastical career, Cyril IV also made several trips to Ethiopia to mediate administrative disputes with the local hierarchy. He also worked to improve inter-ecumenical relations with other Christian denominations in the Middle East.

Reformer, saint, leader, and mystic, Pope Cyril VI is one of the most well-known Copts in history. His visage is found in Coptic homes, churches, books all over the world. He is referred to in this volume as “the last of the traditional popes” in that he traveled only seldomly, making only two trips to Ethiopia during his entire papacy. He also allowed people to see him as needed without an appointment. Cyril VI assumed the Markan throne in the wake of a radically changing country. There was often tension between the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the community council (or majlis al-mili), which had lost much of its power following Nasser’s reforms. For that matter, Nasser’s policies led to the increasing marginalization of Copts in political and public life at large.

Cyril VI was born to well-to-do parents in Menofia. At the age of 25, he entered the monastery of Baramus, taking the name Father Mina. Father Mina led a very austere and ascetic life, despising praise and recognition and fleeing positions of power. Fr. Mina eventually left to inhabit the ruins of the monastery of his patron saint. He later would rent out a windmill in the middle of the Egyptian desert, becoming increasingly ascetic and praying the liturgy daily. In 1944, he was appointed head of the Monastery of St. Samuel of Kalamun, which would later attract the eminent Coptic theologian Matta Al Maskin to its ranks. Becoming patriarch in 1959, some of the highlights of Cyril VI’s papacy includes building close relations with Gamal Abdel Nasser and his nationalist government, the building of new churches and monasteries, particularly a new patriarchal cathedral in Cairo, as well as the foundation of Coptic emigre communities in the west. While famous for his peaceability, asceticism, and spirituality, Cyril VI did not shy away from wielding his ecclesiastical authority to discipline clergy when necessary; as in the case of Matta Al Maskin, when the latter countermanded Cyril VI’s papal order to renovate the Monastery of the Syrians by going to live as a hermit in the desert.

Cyril VI’s successor, Shenouda III, has cemented a reputation for himself as among the most beloved and dynamic popes in Coptic Church history. The beginning of Shenouda’s papacy was marked by increased sectarian tensions in Egypt as well as a direct head-to-head conflict between the head of the Coptic Church and the leader of the Egyptian state, Anwar Al Sadat, who is credited with creating much of the existing sectarian climate in contemporary Egypt. Shenouda had a distinctly autocratic style of Church governance, divesting all authority over the Coptic community from the lay leaders and concentrating it into the papacy and the holy synod. Laymen were discouraged from “doing theology.” Instead, prominent laypeople who were active in Church ministry were ordained into the ranks of the clergy. Shenouda’s conflicts with Matta Al Maskin and the lay scholar George Bebawi became public scandals, and created a rift in Coptic theological discourse which still exists to this day.

Controversies aside, Shenouda was an absolute giant of a churchman and could very well be called the founder of the contemporary Coptic Church. He fostered ecumenical dialogues and signed theological agreements with the Byzantine Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Protestants alike. A staunch patriot, he was keen to promote national unity between Copts and Muslims and worked towards increased cooperation and cohesion between both communities. Shenouda ordained dozens of bishops and oversaw the establishment of Coptic parishes all over Egypt, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Shenouda was also remarkable at engaging with and commanding the love of Copts of all walks of life; the wealthy, the poor, the elderly, and especially the youth. Over 10 years after his passing, his presence, his legacy, and his staunch conservatism still loom large. He almost single handedly transformed the Church from a once obscure national Church into a global communion.

In all, I recommend this volume and indeed the entire “Popes of Egypt” series to anyone interested in the Coptic Church or in Arabic-speaking Christianity in general. Both Guirguis and Doorn-Harder are respected scholars in their fields. Guirguis is an expert in Ottoman era documents and author of An Armenian Artist in Ottoman Egypt: Yuhanna al-Armani and His Coptic Icons, while Doorn-Harder is a professor of Islamic studies at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

What I found particularly fascinating was just how close the Coptic Church came to reunion with Rome in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Especially telling is how the Coptic laity were willing to take recourse to the Islamic authorities when they felt their patriarch was violating church law. I do, however, wish Guirguis had elaborated more on the Coptic Church’s role in the council of Florence in the 15th century, for the sake of providing additional historical context.

While I enjoyed part one more than part two, I thought Doorn-Harder did a good job of describing how the changes in an increasingly modernizing Egypt provided the backdrop for the modernization of the Coptic Church. The conflict between Pope Shenouda and Dr. George Bebawi hearkens the reader back to the dispute between Pope Demetrius and the scholar Origen in the third century. In both cases, we see a charismatic and powerful ecclesiastical authority figure trying to rein in the power and influence of a prominent lay scholar. This, in an attempt to consolidate all theological authority in the hands of the Church’s divinely appointed bishops.

0 notes