#poland's first impressionist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Witold Pruszkowski (Polish, 1846-1896)

Eloe Among the Graves [from Anhelli, Ch. 11], 1892. National Museum, Wrocław

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t the “lack of belief” or being the opposite of religion, but rather being a “surplus of belief”, where different ideas were now more embraced to exist alongside each other. With this idea of Modernism, and with Ezra Pound’s famous proclamation “Make it New!”, I like to see how the art world was influenced by this secularity. Composers were looking at so many different foundations for new sounds and new musical ideas. There was looking back to classical antiquity, Rome and Greece, there was looking at music from East Asia, there was looking WAY back and trying to evoke the music of our pagan ancestors, there was rejecting tonality, there was embracing tonality [a la Strauss], there was marrying to “conflicting” tonalities to make new keys…a lot was going on. And of the composers I’m familiar with, I feel like Karol Szymanowski is the best example of someone being overwhelmed and lost in an era having an identity crisis. Szymanowski’s work is often divided into three periods. The first period is him coming out of Romanticism, following a German tradition [after Wagner and Strauss] of melodies that never end over modulation after modulation, filling the score with as many notes as possible. After a while, he found these works as being too messy and incoherent. After coming across love poems by the Medieval Persian poet Hafez, he fell in love with Middle Eastern and other Mediterranean cultures, and they were the inspiration for a new, more impressionist sound. Near the end of his life he would look back at his homeland of Poland, and incorporate Impressionism with specifically Polish rhythms and subject matter. For now, I’m going to focus on one of his great masterpieces, the “Song of the Night. A choral symphony that is a setting of a poem by another major Medieval Persian poet; Jalal ud-Din Rumi. A bit more like a symphonic poem than a symphony [in Szymanowski’s own words], the work tries to evoke the beauty of nighttime, while also pairing eroticism with religious ecstasy and Eastern mysticism. It’s hard to describe the music with its constantly shifting melodies and harmonies, it sounds like a mix between Wagner, Chopin, and Debussy. And honestly, I couldn’t pick three more completely different composers from each other to put together, but trust me: the music works. Listen, and let the poetry of the music carry you off into nighttime reveries. The work is in one movement divided into three sections: – Moderato assai – Vivace scherzando – Largo

mikrokosmos: Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t…

0 notes

Quote

Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t the “lack of belief” or being the opposite of religion, but rather being a “surplus of belief”, where different ideas were now more embraced to exist alongside each other. With this idea of Modernism, and with Ezra Pound’s famous proclamation “Make it New!”, I like to see how the art world was influenced by this secularity. Composers were looking at so many different foundations for new sounds and new musical ideas. There was looking back to classical antiquity, Rome and Greece, there was looking at music from East Asia, there was looking WAY back and trying to evoke the music of our pagan ancestors, there was rejecting tonality, there was embracing tonality [a la Strauss], there was marrying to “conflicting” tonalities to make new keys…a lot was going on. And of the composers I’m familiar with, I feel like Karol Szymanowski is the best example of someone being overwhelmed and lost in an era having an identity crisis. Szymanowski’s work is often divided into three periods. The first period is him coming out of Romanticism, following a German tradition [after Wagner and Strauss] of melodies that never end over modulation after modulation, filling the score with as many notes as possible. After a while, he found these works as being too messy and incoherent. After coming across love poems by the Medieval Persian poet Hafez, he fell in love with Middle Eastern and other Mediterranean cultures, and they were the inspiration for a new, more impressionist sound. Near the end of his life he would look back at his homeland of Poland, and incorporate Impressionism with specifically Polish rhythms and subject matter. For now, I’m going to focus on one of his great masterpieces, the “Song of the Night. A choral symphony that is a setting of a poem by another major Medieval Persian poet; Jalal ud-Din Rumi. A bit more like a symphonic poem than a symphony [in Szymanowski’s own words], the work tries to evoke the beauty of nighttime, while also pairing eroticism with religious ecstasy and Eastern mysticism. It’s hard to describe the music with its constantly shifting melodies and harmonies, it sounds like a mix between Wagner, Chopin, and Debussy. And honestly, I couldn’t pick three more completely different composers from each other to put together, but trust me: the music works. Listen, and let the poetry of the music carry you off into nighttime reveries. The work is in one movement divided into three sections: – Moderato assai – Vivace scherzando – Largo

mikrokosmos: Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t…

0 notes

Quote

Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t the “lack of belief” or being the opposite of religion, but rather being a “surplus of belief”, where different ideas were now more embraced to exist alongside each other. With this idea of Modernism, and with Ezra Pound’s famous proclamation “Make it New!”, I like to see how the art world was influenced by this secularity. Composers were looking at so many different foundations for new sounds and new musical ideas. There was looking back to classical antiquity, Rome and Greece, there was looking at music from East Asia, there was looking WAY back and trying to evoke the music of our pagan ancestors, there was rejecting tonality, there was embracing tonality [a la Strauss], there was marrying to “conflicting” tonalities to make new keys…a lot was going on. And of the composers I’m familiar with, I feel like Karol Szymanowski is the best example of someone being overwhelmed and lost in an era having an identity crisis. Szymanowski’s work is often divided into three periods. The first period is him coming out of Romanticism, following a German tradition [after Wagner and Strauss] of melodies that never end over modulation after modulation, filling the score with as many notes as possible. After a while, he found these works as being too messy and incoherent. After coming across love poems by the Medieval Persian poet Hafez, he fell in love with Middle Eastern and other Mediterranean cultures, and they were the inspiration for a new, more impressionist sound. Near the end of his life he would look back at his homeland of Poland, and incorporate Impressionism with specifically Polish rhythms and subject matter. For now, I’m going to focus on one of his great masterpieces, the “Song of the Night. A choral symphony that is a setting of a poem by another major Medieval Persian poet; Jalal ud-Din Rumi. A bit more like a symphonic poem than a symphony [in Szymanowski’s own words], the work tries to evoke the beauty of nighttime, while also pairing eroticism with religious ecstasy and Eastern mysticism. It’s hard to describe the music with its constantly shifting melodies and harmonies, it sounds like a mix between Wagner, Chopin, and Debussy. And honestly, I couldn’t pick three more completely different composers from each other to put together, but trust me: the music works. Listen, and let the poetry of the music carry you off into nighttime reveries. The work is in one movement divided into three sections: – Moderato assai – Vivace scherzando – Largo

mikrokosmos: Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t…

0 notes

Quote

Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t the “lack of belief” or being the opposite of religion, but rather being a “surplus of belief”, where different ideas were now more embraced to exist alongside each other. With this idea of Modernism, and with Ezra Pound’s famous proclamation “Make it New!”, I like to see how the art world was influenced by this secularity. Composers were looking at so many different foundations for new sounds and new musical ideas. There was looking back to classical antiquity, Rome and Greece, there was looking at music from East Asia, there was looking WAY back and trying to evoke the music of our pagan ancestors, there was rejecting tonality, there was embracing tonality [a la Strauss], there was marrying to “conflicting” tonalities to make new keys…a lot was going on. And of the composers I’m familiar with, I feel like Karol Szymanowski is the best example of someone being overwhelmed and lost in an era having an identity crisis. Szymanowski’s work is often divided into three periods. The first period is him coming out of Romanticism, following a German tradition [after Wagner and Strauss] of melodies that never end over modulation after modulation, filling the score with as many notes as possible. After a while, he found these works as being too messy and incoherent. After coming across love poems by the Medieval Persian poet Hafez, he fell in love with Middle Eastern and other Mediterranean cultures, and they were the inspiration for a new, more impressionist sound. Near the end of his life he would look back at his homeland of Poland, and incorporate Impressionism with specifically Polish rhythms and subject matter. For now, I’m going to focus on one of his great masterpieces, the “Song of the Night. A choral symphony that is a setting of a poem by another major Medieval Persian poet; Jalal ud-Din Rumi. A bit more like a symphonic poem than a symphony [in Szymanowski’s own words], the work tries to evoke the beauty of nighttime, while also pairing eroticism with religious ecstasy and Eastern mysticism. It’s hard to describe the music with its constantly shifting melodies and harmonies, it sounds like a mix between Wagner, Chopin, and Debussy. And honestly, I couldn’t pick three more completely different composers from each other to put together, but trust me: the music works. Listen, and let the poetry of the music carry you off into nighttime reveries. The work is in one movement divided into three sections: – Moderato assai – Vivace scherzando – Largo

mikrokosmos: Szymanowski – Symphony no.3 “The Song of the Night” In college I took a corse on Modern Literature, Modern meaning the cultural shift that happened around the turn of the century and continued to WWII. I don’t remember the name of the essayist, but we had read one piece that argued Secularism, and Secularity, wasn’t…

0 notes

Text

Oct 11 (Stage 2)

Morning Session

Federico Gad Crema (Italy) Fazioli; is he playing like three polonaises??

Polonaise-Fantasy in A flat major, Op. 61: it sure was more fantasy than polonaise... Very nice accord-y, melancholic theme in lower notes.

Polonaise in C sharp minor, Op. 26 No. 1: I liked left hand in the middle, more melancholic part.

Polonaise in E flat minor, Op. 26 No. 2: interesting contrasts. I liked the more marching parts, overall it was quite a marching polonaise.

Waltz in A flat major, Op. 42: very lively.

Rec: Polonaise in E flat

Alberto Ferro (Italy)

Waltz in E flat major, Op. 18: quite lovely, very nice ending.

Ballade in F minor, Op. 52: I like how every time the main theme came, he played it a bit differently, also there was probably one lil crescendo in terms of this theme throughout the whole piece. Overall, it was kept in the same level of emotions and dynamics, baring some moments like the ending.

Andante spianato and grand polonaise in E flat major, Op. 22: oh, and spianato for the n-th time... But it was nice, I liked left hand in the main motif. Polonaise: he's def an elegant pianist and the polonaise shows it's not only in his appearance. I liked (again) his left hand---very precise, and made this polonaise character nicely.

Rec: Andante spianato and grand polonaise

PR 2 recs: H. Choi: prelude as an introduction to scherzo; a pianist reaching for poetic and epic sound. Good tonations choice. A dramatic, melancholic, nocturnal pianist. But this maybe doesn't work for scherzo? Which was quite grave. Waltz pearly, contrasted, second half better than the first, played with imagination, brillante even if not in the type of i.e. Bunin's. Ballade interesting, second theme quite impressionistic. Polonaise: introduction is generally very hard, only maybe A. Wierciński was able to play it, Choi played it interestingly, esp in the second part. Best: prelude in C sharp minor. | F. G. Crema: he's generale quite individualistic. Polonaise: at the end, while playing forte, Fazioli rumbled a bit. Deceptive fantasiness of fantasy---he didn't extract the polonaise part. Op. 26: very individualistic, E flat played very secco, quite marchingly, overall good. He contrasted op. 26 very well, even if the polonaiseness was quite "from Italy to Poland". The presenters were glad/impressed maybe? that he chose those two "melancholic" polonaises, since they aren't popular. Waltz: his own, but interesting. Overall interesting, only dances, which the presenters count as a good choice in the state which concentrates on dances. From the interview: he loves dancing ;) he also likes fashion and became an ambassador for some brands, so we can expect new suits. ("Remember, Chopin was a dandee", said one of the presenters.) | A. Ferro: more predictable, a classical restraint."A recital of a genre of those that may be played, but don't need to". A bit of disappointment?... Waltz was the most akin. Andante without pauses, polonaise---quite a bunch of mistakes.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Lidia (it’s undercover work 😉)

First five asks get a kiss!

1/5

Lidia Sobieska has told her share of lies as a politician, but this she must admit: he's gorgeous. It's the scars. He wears them with such decorum, she's tempted to ask the Agencja Wywiadu to dig up how he got them.

"I will tell you mine if you tell me yours. An exchange of foreign intelligence, no?"

The restaurant is an Impressionist painting in sunrise and cornflower blue. They share it only with Lidia's bodyguards and handpicked waitstaff. She wishes he had let his hair down. Perhaps there will be opportunity for it as the evening progresses.

Dragunov takes a breath as if to speak, then lets it go on a quiet chuckle, lip curling in a hint of a smirk. Lidia imagines he's thinking back on decades of history between their countries. Military to the core. She doesn't mind if he doesn't talk. It's a pleasant change of pace from chirping advisors, clanging cabinet members.

"A hint?" Lidia draws a finger down her left eye. "Mine fell out of the blue. There. Now it is your turn."

Sergei stares at his roast quail and truffle ragout as if it's offering battle tactics. Finally, deliberately, he runs his thumb across the bridge of his nose, then holds his hands up crossed at the wrist, mirroring each other, fingers splayed.

"A bird?" Lidia smiles. "I imagine it took no less than a basilisk to get its claws on you."

Dragunov shakes his head. A strand of black slips free to fall past his ear. "Orel," he murmurs.

Lidia's phone vibrates. Excusing herself, she checks it. It's a text from her guard detail, translating what he said.

She can't help her cheeks turning as red as the coat of arms.

- - -

She kisses him before they leave, not even annoyed she must rise on tiptoe to do so. She can't remember the last time she felt so charmed. Her heart surges as he keeps it chaste, hands in her own. Little wonder he is called an angel.

"We will meet again," she says, "In the ring or outside it."

Sergei nods. He looks forward to it.

- - -

That night, back in his hotel room, he cannot sleep. Lying on his side, he stares out at Warsaw, a pillow crushed to his chest.

He should pursue her. She is the prime minister of Poland. She has a country at her beck and call. Money, power, connections, a fairy tale any of his fellow spetsnaz would kill for, yet his heart convulses at the thought of a second date. If she were a man--

You are broken, repeats his thoughts, You are broken.

Dragunov gets up, raids the fridge for a glass of whiskey, and downs it in a single gulp. The lights outside reflect off the cup as he pours another. He has held men underwater until they expired. Tonight, he will drown himself.

#veladora#( oops this is feels )#memes ; (had fun once; it was awful)#( things that will force dragunov to talk: )#( pretending to be straight :puke: )

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer Composers

For Pride Month, I would like to share a list of some of my favorite queer composers. Being queer doesn’t matter when talking about the music, and there is no other commonality that pairs these composers together. The point isn’t to say that queerness makes their music more valuable or influences their music, rather the point is to recognize diversity, and to acknowledge queer visibility. I understand the people who scratch their heads or roll their eyes at the idea of bringing up queer composers, and to them I say the point is simply to recognize their existence, because prejudices and biases through time have worked on erasing or revising history in order to keep hidden this aspect of the human condition. You could shrug and say “Who cares if Tchaikovsky was gay?” and I would say, “You’re right, it doesn’t matter much outside of biographies, but if you acknowledged Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality in Russia you could be arrested for “promoting gay propaganda”. I am also motivated by a comment from a friend who admitted they think the concept of “Pride” for anything you cannot control is “idiotic”. My response can be summed up as, when a group has been shamed for years for their identity, they will be ready to sing about it from the mountaintops when it is accepted. In other words, it is not about who is better or worse, rather it is the opposite of shame, and hopefully putting a human face on something that a lot of people only consider in the abstract.

In no particular order, here is some cool music by some queer people;

Tchaikovsky: Possibly the greatest composer in Russian history, and one of the greatest composers in general. Pyotr Illych Tchaikovsky wrote in multiple genre, from symphonies to concertos to ballets, chamber music, opera…and while he can be criticized for the way he develops themes, his music is melodic and passionate and brimming with life. Among my favorites are his fourth symphony, the second piano concerto, the first orchestral suite, his piano trio, and his concert fantasy.

Poulenc: One of the members of Les Six, a group of Modernist French composers who were reacting against “overblown” Post-Romantic music, and methodical 12-tone serialism, Francis Poulenc can be described as a “neo-classicist”, sometimes his music resembles Stravinsky. The music tends to mix two unlikely moods: goofy, fun melodies and rhythms, and solemn religious contemplation. Cosmopolitan and Catholic, Poulenc was able to juxtapose opposite ends of the spectrum of the human condition; our vulgarity and profanity, and our spirituality and the desire for divine connection. My favorite works by him are his Organ Concerto, his harpsichord concerto “Concert-champêtre”, the concerto for two pianos, the cello sonata, and his Gloria.

Smyth: An English composer and an important figure in the Woman’s Suffrage movement, Ethel Smyth was a Post-Romantic who wrote powerful music lively with the British sense of nobility and strength. In the same ironic tragedy Beethoven went through, Smyth started to lose her hearing from 1913 onward, and so she gave up composing in favor of writing. While that is a shame, she left behind a good handful of orchestral and chamber music. My favorites by her are the overture to one of her operas, The Wreckers, her serenade which is kind of evocative of Brahms, and her gargantuan Mass in D Major.

Szymanowski: A Polish composer from the first half of the 20th century whose life can be seen as a narrative of seeking identity. Karol Szymanowski started out writing in the Post Romantic German style, with dense textures and a lot of chromatic modulation, but he was losing interest in this idiom quickly. He was inspired by Persian poetry he came across, and started writing in an Impressionistic way focusing on Mediterranean cultures, influenced by Greek and Roman mythology, Middle Eastern poetry, and the atmosphere of the Mediterranean as being a diverse mixing of cultures. Later in his life, he decided to look back at Poland for inspiration and finally found his “authentic” Polish identity in music inspired by the folk stories and Catholicism of Poland. My favorite works by him are his nocturne and tarantella for violin and piano, his song cycle the Love Songs of Hafiz, the third symphony, and his Stabat Mater.

Barber: It’s possible to say that Samuel Barber’s music is a good representative of American culture…a diverse mix of differences that complement each other. He took after jazz and blues, and after experiments in tonality heard in Europe and other American composers like Charles Ives, and he took after Romanticism with deep and powerful music. My favorite works by him are the Adagio for Strings which is heavily inspired by Mahler, his piano concerto, and Knoxville: Summer of 1915.

Copland: Another great portrait of America, Aaron Copland was considered one of the quintessential “American” composers of the 20th century, despite the combined factors of being gay, Jewish, leftist, and inspired by Russian and French modernism. All of those were seen as outsiders of the general American public. Even so, taking after Stravinsky, Copland’s music is full of spaciousness and open chords, melodies that range from longing to folksy and fun. My favorite works by him are his clarinet concerto, violin sonata, fanfare for the common man, and his ballet Appalachian Spring.

And if you reblog this list, feel free to add any of your favorite queer composers and share their music, their names, their faces.

#happy pride 🌈#composers#music recommendation#gay composers#queer composers#lgbt composers#classical#classical music#music#pride#pride month#happy pride#queer visibility

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movies I watched this Week #96

My neighbor Adolf, a strange new Israeli comedy, which was produced in Poland and filmed in Colombia. It’s about an old Holocaust survivor in 1960 who suspects that his mysterious German neighbor is Hitler. The tone is shifted from comedy to horror, the score is jarring, and Udo Kier is terrific. Interesting oddity - 7/10.

🍿

2 non-narrative poems by Ron Fricke:

🍿 After serving as the cinematographer on Koyaanisqats, Ron Fricke branched on his own to direct 4 time-lapse abstract poems in a similar large scale style. Chronos was his first. A musical essay about the passage of time.

It’s hard to believe it’s from 1985. Unfortunately, it’s only 42 minutes long. Best of the week!

🍿 Re-watch: Baraka, AKA “Breathing” in Sufi. His next impressionistic, non-verbal, majestic trip across the world. But also includes darker segments about mass destruction, poverty, homelessness, mass murder, animal farming

🍿

Sweetheart, a sweet new British comedy about a confused 17-year-old girl on holiday camp with her family, as she awkwardly falls in love with another girl. 100% “Fresh” reviews on ‘Rotten Tomatoes’. I loved it. 7/10. (Photo Above).

🍿

5 by veteran Bruce Beresford: 🍿 His most recent, Ladies in Black, was recommended to me by my 92-year-old mother, who read the Australian book about a group of female employees in a hi-scale department store in 1959 Sydney. I did not expect to like it so much. More than a feel good “chick flick” reminiscent of ‘Carol’, it’s a nuanced and nostalgic feminist tale, well-told. 7/10.

🍿"...Were you really Mac Sledge?" ... "Yes ma'am, I guess I was..."

First watch: Tender Mercies, a tender story about an alcoholic country singer who finds peace and redemption with a young widow outside Waxahachie, Texas. Robert Duvall sang (his own) songs. This was Tess Harper debut film. 8/10.

🍿 “...Hoke? ...Yes'm....You're my best friend...”.

Driving Miss Daisy, his very popular drama about the relationship between old Jewish Jessica Tandy and her subservient black chauffeur Morgan Freemen starting in 1940′s Atlanta, GA and continuing for 25 years. Tandy became the oldest actress to win an Oscar, by playing a 72-year-old woman who than ages through the decades. With an early catchy score by Hans Zimmer. 9/10.

🍿 In 1987 he participated in Aria, a 10-director anthology interpreting various opera scenes, mostly by the Europeans, Verdi, Puccini, Wagner, Lully, Etc. The line-up was impressive: Godard, Julien Temple, Robert Altman, Ken Russell...

Every reviewer at the time had a different opinion which of the segments were ‘successful’ and which failed. I was taken in by the first remarkable few by Nicolas Roeg and Charles Sturridge, But eventually the whole concept proved to be just music videos of Operas, and fizzled out. Bridget Fonda and Elizabeth Hurley had their debut performances here, and very young Tilda Swinton too. The music of course was superb.

🍿 Re-watch: His Australian breakthrough film Breaker Morant, about the first war crime trial in the history of the British military. A real life story of the 3 Australian soldiers who were court marshaled for murder of some prisoners, “The scapegoats of British Empire". Old-fashioned war films, especially about a far-away war like the Anglo-Boer War, are not too interesting, but the last 25 minutes were brilliant.

🍿

So 2 more by Ken Russell:

🍿 Women in love, his adaptation of D H Lawrence’s bohemian novel, about sex and the upper class before the war. It’s a modern story of the relationships of two sisters of working-class background and two male friends, who also have strong attraction for each other. An early script by Larry Kramer.

Including some famous scenes, notably a nude wrestling scene between Bates and Reed and "The proper way to eat a fig”.

🍿 Ken Russell’s very last film, A Kitten for Hitler, (”Ein Kitten für Hitler”), is an offensive, politically-incorrect 2007 short. It tells of a little Jewish boy (played by a real Oompa-Loompa dwarf) in 1941 Brooklyn, NY who travels to give Hitler a gift of a kitten in order to soften his heart, so he won’t be so cruel. But the boy ends up as a lampshade on Eva Braun’s side of their bed. So yeah, a typical Pink Flamingo type dog shit bomb by the 80-year-old Russell.

🍿

Argentina, 1985, based on true events, is a new courtroom drama about the brave prosecutor who led the “Trial of the Juntas”. I knew about the ‘Disappeared”, but was not too familiar with the details of that period in Argentinian history. After 8 years of brutal dictatorship, this trial was the opening chapter in the struggle for democracy that has lasted until now. Interesting topic, formulaic execution. 5/10.

(I was planning to follow this with ‘The official Story’, the 1985 story about ‘The dirty War’, which was the first Argentinian film ever to win an Oscar, but didn’t manage. Back on the list it goes)..

🍿

I was looking forward to Weird: The al Yankovic Story, the ‘Funny and die’ spoof, and hoped it will slap, but it was a big disappointment: It was a flat and dumb parody about a parodist, not funny or clever. And so many cameos: Dali, Divine, Hulk Hogan, Conan O'Brien as Andy Warhol, Coolio... 1/10.

🍿

Woody Allen’s 2nd slapstick comedy Take the Money and Run, from the time when he was still funny (“He earned a meager living selling meagers”) and before he started molesting young girls. Strange to think that his self-depreciated nervousness was once considered a romantic trait.

🍿

A bit more Guilty Pleasure: I saw the complete ‘Breaking Bad’ about 3 times before, and so I just went back to the series final Felina once again. It’s about revenge: The most dramatic scene is the machine Gun Massacre, but the rest of the episode is very quiet, introspective and emotional conclusion to this perfectly-complicated story.

🍿

Throw-back to the art project:

Morgan Freeman Adora.

Breaking Bad Adora.

🍿

(My complete movie list is here)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Loving Vincent (2017)

Loving Vincent is as ambitious as any film could be. Co-directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, this movie concentrates on piecing together the events leading to Vincent van Gogh’s death. But it is not the storytelling – flawed, sometimes tedious at times – that has caught the attention of movie lovers, especially those who care about animation in film. Instead, it is because Loving Vincent is the first animated feature entirely composed of paintings. These oil paintings have been rendered in the Post-Impressionist style of Van Gogh himself (as well as some charcoal sketches), with a team of more than a hundred painters spread out across Greece and Poland: Athens, Gdańsk, Wrocław. With financing from Poland and Britain and elsewhere, the film is also the result of an unstoppable trend in independent animated cinema – cooperation across borders, the globalization and universality of art – that might not have been possible at any earlier time.

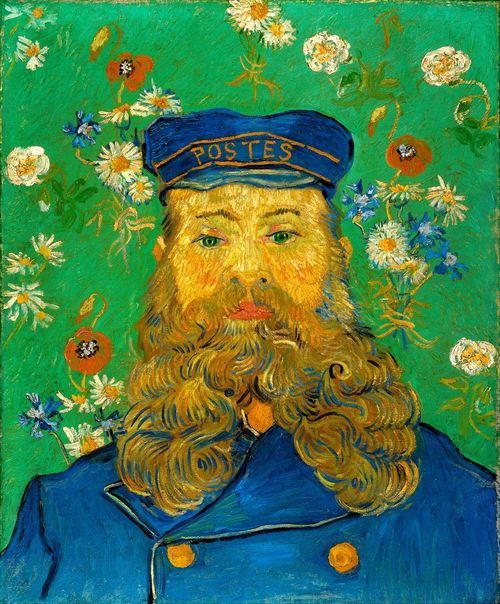

Those looking for a conventional biopic for Van Gogh will be disappointed, as Loving Vincent is retrospective (like a cross between Citizen Kane and Rashômon). It begins one year after Van Gogh’s (Robert Gulaczyk) suicide with Arman Roulin (voiced by Douglas Booth; all actors have been Rotoscoped into the film), the eldest son of Postman Roulin (Chris O’Dowd), being tasked by his father to deliver Van Gogh’s final letter to his younger brother, Theo van Gogh. Several attempts to send the letter to Theo have failed; Armand is later informed by Père Tanguy (John Sessions) that Theo died shortly after his brother’s death. Armand, having spent more time on this delivery than he intended and with no next-of-kin/non-estranged family remaining, is now looking to deliver the letter to someone who was very close to the famed painter. He travels to Auvers-sur-Oise, a Parisian suburb where Van Gogh lived, worked, and died, and asks for assistance. There, Armand will meet the locals that knew Van Gogh best – noting their wildly conflicting accounts of the artist’s final days, he attempts to piece together a coherent story of what happened leading up to Van Gogh’s death.

Within fifteen or twenty minutes, Loving Vincent’s narrative structure begins to reveal itself and stays that way until the final moments. As Armand Roulin navigates the French countryside, he encounters other characters like Louise Chevalier (Helen McCrory), Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), a boatman (Aidan Turner), Marguerite Gachet (Saoirse Ronan), a Dr. Maery (Bill Thomas), and a Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn), one begins to notice that the characters are based on their appearances in some of Van Gogh’s portraits – some invented, others being the painter’s real-life friends and acquaintances. Armand and Joseph Roulin, too, were subjects of some of Van Gogh’s most famous paintings. Most all of them are willing to talk about Van Gogh to Armand. Either these people have not spoken about his death in the longest time or have few inhibitions as they seem too willing to tell Armand what they thought of the resident artist. In these sit-downs with this cast of characters, the movie reverts from the colorful oil paintings of the present to the black-and-white charcoal drawings which represent the recent past.

Sequences roughly follow this format: Armand asks around where he can find a person/if he is in the right place, someone responds affirmatively and introductions are made, Armand reveals his postal tasks, and the person who introduced themselves to Armand engages in a long-winded reflection (this is where the black-and-white charcoal sketches arrive) of what they thought about Vincent van Gogh and what they saw and heard in his final days. Was Van Gogh’s death murder? A suicide as is commonly accepted? Some of these figures recalling their stories to Armand take more time than others. Other testimonies are more revealing too – like that of Dr. Gachet (who treated Van Gogh after his release from an asylum and shortly before his death), who speculates on the artist’s psychology and mental health. His daughter, Marguerite, is reflective of the Van Gogh she knew of that others never did – a man finding joy in the smallest natural details, looking to bring beauty to life, and subjected to verbal harassment and ostracization from the locals. Despite some of these interesting portions, after the third or fourth bit of storytelling from a supporting character, the film’s rhythms become repetitive and analytically monotonous.

With all the makings of a classic of feature animation – one with a style never seen in cinema before – it is a shame that Loving Vincent never experiments with its story structure or employ a more interesting one to watch. Perhaps I am writing as a person who is not as art history literate as I probably should be. But as fascinating as the film’s aesthetic is, it cannot fully resolve the deficiencies of the screenplay by Kobiela, Welchman, and Jacek Dehnel. Loving Vincent wanders too often without direction, precision.

Before the actual painting for Loving Vincent began, Kobiela and Welchman decided to film the action with their voice actors modeling their respective characters (shooting took twelve days; here is a picture of Saoirse Ronan modeling as Marguerite Gachet), Rotoscoping their movements to achieve some understanding of how characters should move their bodies and adjust their faces. If Loving Vincent were live-action, it certainly would have contained a handful of recognizable actors. But the final product of the Rotoscoping before painting has provided for incredibly smooth movement within scenes, like a dreamland endowed with reality. During the non-black-and-white scenes, one can pick out hundreds of brush strokes during each frame, noticing some that disappear when a character is moving (the painters used spatulas to scrape off the painting after completing a single frame). A selected number of these paintings are currently being sold on the film’s website.

The dimensions of Van Gogh’s canvasses posed some difficulty for the one hundred and twenty-five animator-painters that eventually worked on the film (selected from 5,000 applicants worldwide, a process culminating in a three-day audition in Gdańsk). Loving Vincent is shot in 4:3 (1.33:1), and a little less than half of Van Gogh’s portraits were on 4:3 canvasses. But some of the paintings alluded to in the film are either too long or too wide for a 4:3 screen aspect ratio. Take Café Terrace at Night. Sufficiently wide but too long for 4:3, Kobiela and Welchman decide to pan the camera downwards. What about Marguerite Gachet at the Piano, another long portrait but does not lend itself to panning? For that piece’s implementation into Loving Vincent, the crew researched what could plausibly be added to fill in the left and right. A few of Van Gogh’s portraits reverted from daytime into nighttime (and vice versa); other portraits changed seasons to suit the summer heat Armand and the Auvers-sur-Oise residents are sweltering through.

Vincent van Gogh’s works remain untouchable. 65,000 frames and eight hundred and fifty-three different oil paintings do little to change that. And though art historians and auctioneers can dismiss the artwork in Loving Vincent as copies, note that these images – unlike van Gogh’s – were created for the sake of movement. Though both Van Gogh and the hundreds of animator-painters both engage in portraiture, the artistic mediums they are working in are very different.

The music is composed by Clint Mansell (Darren Aronofsky’s favored composer, with credits including 2000′s Requiem for a Dream and 2010′s Black Swan). I admittedly am not a fan of Mansell, who prefers ambient textures and minimalism rather than recognizable melodies (although, if one day he becomes less melody-averse, Mansell is one of the better composers who can combine synthetic and acoustic elements). That trend does not reverse here, but Mansell’s music sets the moods brilliantly – especially in cues like “The Night Cafe” (suggesting restlessness and the unlit corners of the world at night) and “The Sower with Setting Sun”. The music works for Loving Vincent in establishing tone, but has little vitality listened to independently from the film. Lianne La Havas’ cover of Don McLean’s “Vincent” is a gorgeous coda, appearing at the start of the end credits.

Loving Vincent never captures the disturbed mentality of Van Gogh as seen in Kirk Douglas’ performance in Lust for Life (1956). It never surpasses the wonderment expressed in the vignette, “Crows”, found in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (1990, Japan) where Akira Terao steps inside the portraits of Vincent van Gogh – figuratively and literally. So where does Loving Vincent figure in cinematic speculations, fever dreams, and fantasies about Van Gogh’s work?

Perhaps it is that some artists (to extend the definition, those who create) that are removed from us by history are unknowable. This includes anybody working in any medium, and truer for some artists than others. It might have been especially true for Vincent van Gogh. His life was his work, and that is where you can find him and know him. In his dying days, Van Gogh’s artistry and his personhood became indistinguishable. That is where Loving Vincent succeeds – humanizing that which can never be described, but experienced.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lush island landscape in Polish lake captured from above

Earth 19 February 2020

By Bethan Ackerley

Kacper Kowalski

Photographer Kacper Kowalski

THIS speckled diamond looks like it belongs in an Impressionist painting. In fact, it is a photo of a small island in a lake in northern Poland.

Advertisement

The image comes from Side Effects, a project by aerial photographer Kacper Kowalski about the complex relationship between humans and nature. To shoot his photos, Kowalski takes to the air in a paramotor or a gyrocopter, which he barely steers to allow the wind to dictate the direction. He sticks to the skies of Pomerania, surrounding his home …

Existing subscribers, please log in with your email address to link your account access.

Paid annually by Credit Card

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

*Free book is only available with annual subscription purchases where subscription delivery is in the United Kingdom, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand or Euro area

Read More

The post Lush island landscape in Polish lake captured from above appeared first on Gadgets To Make Life Easier.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2PI86hs via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Shocking Paris: fascinating background on 20th-century Jewish painters in Paris "Shocking Paris" focuses on several artists who worked in the Montparnasse district of Paris in the early part of the 20th century. A generation younger than the impressionists, they tended to be Jewish emigres from both Russia itself and the Czarist-controlled "Russian Pale" satellites of Lithuania, Belarus, and Poland, although one prominent member of their circle was the Italian Jew Amedeo Modigliani. As the subtitle indicates, the book devotes its greatest attention to Chaim Soutine and Marc Chagall. Go to Amazon

Superb Art History work of the School of Paris With the utmost satisfaction I wish to rate this book by Stanley Meisler with 5 stars. Mr. Meisler wrote a superb work of art history, and to increase our understating, he weaved into his book the troubled period of European history in the first half of the Twentieth Century between both World Wars. Since most of the artists of the School of Paris are Jewish, he addresses the difficult issues of antisemitism, the origins of those artists, some born within the realm of urban sophistication (Modigliani) others born into despairing poverty in segregated areas (Soutine), rising up the ladder of art and society with their outstanding work. This book increased my understating of the works of art I admire when I visit Museums with my wife, and I strongly recommend it. Personal disclosure: Stanley Meisler is a great neighbor of mine! Go to Amazon

Af times this is a painful and heroic overview of difficult and memorable lives of ... So you want to be an artist? A Soutine type? Well think again - Stanley Meisler will surely bring you back to reality. This is an insightful book on the Go to Amazon

Terrific! A fascinating and important story about these artists and an extremely well told one. I was impressed with the very thoughtful and thorough research but was even more impressed with the author's clear and very engaging style. I found I couldn't put it down! I downloaded, started and finished it while on a 2 week trip to Paris. The book inspired more than one visit to Musee de l'Orangerie to see the works up close and a long walk around Montparnasse. Well done Mr. Meisler - thank you! Go to Amazon

Wonderful! Well written, captivating art history and personal insight to artists from the School of Paris time period. I learned so much about Soutine who I was unfamiliar with, as well as the other artists of this time period. The author was able to connect the impact of World War I and II, anti-Semitic rhetoric and fear on these immigrant artists all who had made Paris their home. Go to Amazon

A wonderful book about Paris and especially Soutine! This is a wonderful book, introducing Soutine to all of us who wondered about him but didn't know. Lovely writing, so generous to the reader as well as to the subject matter. Straightforward, detailed, human. I really appreciated Meisler's gift. Thank you. Go to Amazon

limited material... evident that it was written ... limited material ...evident that it was written by a jounalist! Go to Amazon

Just the facts My husband and I both found this book very boring. This book did not give a person any of the excitement of the lives of these artists. Go to Amazon

Art History Montparnasse what a neighborhood Great book, very interesting Five Stars I bought several books as gifts for friends who all loved it. Thoroughly enjoyed this book Three Stars This could have been the real life of Soutine....

1 note

·

View note

Text

10. UNITED KINGDOM

Lucie Jones - “Never give up on you” 15th place

youtube

I will forever be grateful that, in this late day and age, the Eurovision Gods still managed to deliver a UK entry that I not only enjoyed, but loved. Lucie is the best UK entrant since the inception of televoting, yes?

This year was the first time in forever that I felt the UK *understood* Eurovision and it was about fucking time too. When it comes to losing the plot, the UK is always the go-to Eurovision nation. Spearheaded by Terry Wogan’s delusions (I love terry wogan dearly but dude blamed Jemeni’s null points on the Iraq War lmfao wat), the UK were so out of touch with reality that they kept on pelting us with entries which were not only poor in result and but also rich in second-hand embarrassment. It looks as though the curse was lifted this year though :throws confetti:

Still, it LOOKED as though it would be the Same Old with the UK as the BBC chose to host a national final which was LESS THAN AN HOUR LONG lmfao. Naturally, it was a horriic timewaste (despite featuring Mel Giedroyc, Sophie Ellis-Bextor and Bruno Tonioli) at least we were given an adequate winner from that otherwise horrific show. Sure, “Never give up on you” was boring, but at least it wasn’t outright bad!!

But as we know, the UNTHINKABLE happened and the BBC decided to revamp their entry :o.

The first step involved adding instrumentation to "Never give up on you”, ensuring it no longer was the Most Boring Song Ever. The end result spoke for itself, it provided Made of Stars-levels of emotionalised realness and I really dug that.

The second (secretive) step was replacing Lucie Jones with a life-like android counterpart which was is programmed to look, sound and behave exactly like her.

Unfortunately, due to the heat from the spotlights and the clamour from the audience, the LucieBot 3000 short-circuited into malfunction and instead performed like this:

Error 404 - Brain Not Found

Like, I seriously loooooooove The Face we were given, but with that in mind it’s no surprise this got a meager 25 points from the audience lol. (yeah, people keep saying BREXIT but I think they exaggerate its impact. Political shit only really influences results when it’s (1) Russia or (2) directly related to the entrant themselves).

STILL, this starry impressionist Birth-of-Venus-like staging HAS to signify the birth of a new Era of Eurovision Dominance for the UK, right? RIGHT??? *takes out rosary*

Decade Rank: 67/324

THE 2017 RANKING SO FAR:

-ADORE- 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. -LOVE- 7. 8. 9. 10. United Kingdom (67/324) 11. Finland (68/324) 12. Estonia (71/324) 13. Azerbaijan (84/324) 14. Latvia (87/324) 15. Israel (93/324)

-LIKE- 16. Bulgaria (100/324) 17. Portugal (105/324) 18. Croatia (115/324) 19. Austria (119/324) 20. France (138/324) 21. Poland (154/324) 22. Armenia (158/324) 23. Romania (164/324)

-OKAY- 24. Iceland (174/324) 25. Ukraine (190/324) 26. San Marino (203/324) 27. Albania (217/324) 28. Denmark (228/324) 29. Spain (237/324) 30. Cyprus (240/324) -DISLIKE- 31. Germany (258/324) 32. Montenegro (263/324) 33. Sweden (270/324) 34. Serbia (275/324) 35. Australia (280/324) 36. Switzerland (286/324) 37. Czech Republic (288/324) 38. Malta (291/324) -HATE- 39. Georgia (301/324) 40. Greece (303/324) 41. Slovenia (307/324) 42. Ireland (312/324)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Full Trailer for ‘Loving Vincent’ Is Finally Released! Watch the Exclusive of the Short-Film Animated by 62,450 Oil Paintings

The full trailer for Loving Vincent recently dropped with an ambitious agenda, to imitate the Dutch artist’s signature, expressive brushstroke in a series of oil paintings to construct an animated film. Featuring some of the painter’s most famous works, the first fully painted feature film in the world will chronicle Vincent van Gogh’s life story and tumultuous history, leading to his mysterious death.

Directed by Polish painter and director Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman (Oscar winner for producing "Peter and the Wolf"), the cinematic piece is still in production by Oscar-winning Studios Breakthru Films and Trademark Films.

Composed solely by hand painted canvases, the enormous project, utilized over 100 painters’ skill in replicating the post-impressionist master’s brooding and expressive brush stroke technique.

Made in the seaside and party city of Gdansk Poland, the studio is still searching for high-level oil painters.To become part of the initiate, you can contribute to their Kickstarter campaign, as well as oversee their progress on their website.

youtube

youtube

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Famed Jewish Art Dealer Who Fought to Retrieve 400 Stolen Works from the Nazis

The Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888. Vincent van Gogh Rijksmuseum Kroeller-Mueller, Otterlo

Vincent van Gogh, La Mousmé, 1888. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In October 1919, Parisian dealer Paul Rosenberg opened his first solo exhibition by a recent addition to his gallery roster, Pablo Picasso. The startling display of 167 drawings and watercolors marked a dramatic break with the Cubist style Picasso had helped popularize, and the beginning of an important partnership between the artist and Rosenberg that would last until 1940, when the dealer was forced to flee France as the Nazis advanced.

In those two intervening decades, Rosenberg became the world’s most important art dealer, representing not only Picasso, but also Georges Braque beginning in 1923, Fernand Léger as of 1926, and Henri Matisse starting in 1936. Rosenberg’s two-story gallery at 21 Rue la Boétie in Paris’s 8th Arrondissement came to be known as the “French Florence,” described by French art critic and historian Pierre Nahon as “an essential meeting place for everyone who wants to follow the development and the work of the innovative painters.”

Shortly after the opening of that first Picasso show in 1919, Rosenberg, who lived with his family in the apartments above the gallery, convinced the artist to move into a vacant flat next door at 23 Rue la Boétie. The business partners suddenly became neighbors and fast friends, visiting each other regularly and referring to each other as “Pic” and “Rosi” in their frequent correspondence. According to Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, during this period, the artist would sometimes step onto his balcony and wave his latest canvas until he got Rosenberg’s attention. It was one of modern art’s most important and mutually advantageous relationships; or, as Nahon later wrote: “The artist and the gallery owner made one another.”

A family affair

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge, 1892–95. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul Rosenberg owed some of his savvy as a dealer to his father, who nurtured in him both a refined eye and sharp business sense. Unlike his brother Léonce—whose Galerie de l’Effort Moderne had represented Picasso for the three years prior to Paul poaching him—Paul understood that he would have to balance support for avant-garde artists with sales of works by more established figures, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet.

Paul and Léonce had grown up among such works after their father, Alexandre Rosenberg, left a career as a grain merchant to become an antiques dealer, eventually falling hard for the Impressionists. By the time he was 16, Paul began working for his father and honing his eye. When he was just 19, Paul’s father dispatched him to London to open an outpost of the family business. He had mixed results across the English Channel, though he did manage to buy two Vincent van Gogh drawings for £40. Back in Paris, Alexandre Rosenberg set up his sons with a space on the Avenue de l’Opéra in 1906 to carry on the family business after he retired, but Paul quickly grew listless.

“I was successful, but I was troubled by the idea that I was selling paintings I didn’t like,” he later wrote in an unfinished memoir quoted by his granddaughter, journalist Anne Sinclair, in her 2012 book My Grandfather’s Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War. “I realized that if I were going to compete with the big auction houses of the day, I needed to buy only the highest-quality works, and rely on time to make a name for myself.”

Over the next four decades, Paul would do just that, striking out on his own and, in 1912, opening his gallery at 21 Rue la Boétie. There, according to an announcement laying out his program for the space, Paul planned to show a mix of works by acknowledged 19th-century masters and pathbreaking contemporary painters. In the same announcement, he made clear that his gallery would be no ordinary showroom, pledging to fund the publication of catalogues for every show and writing that “the shortcoming of contemporary exhibitions is that they show an artist’s work in isolation. So I intend to hold group exhibitions of decorative art.”

And so it was that Paul’s adventurous exhibition program mixed Théodore Géricault, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Gustave Courbet with Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Marie Laurencin, and Amedeo Modigliani. And though he was a great promoter of the avant-garde art of his day, Rosenberg still had his prejudices. Surrealism, for instance, was of absolutely no interest to him. It’s said that Salvador Dalí once approached him in a restaurant to ask if he’d be interested in representing him, and the dealer shot back: “Monsieur, my gallery is a serious institution, not made for clowns.”

But Rosenberg was completely devoted to the artists in whom he believed. He was a relentless champion of their work with museums, loaning works for major exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. In consultation with his friend Alfred H. Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art, he loaned more than 30 paintings to the institution for the blockbuster exhibition “Picasso: Forty Years of His Art.” The timing of that exhibition, which opened in New York City on November 15, 1939, was darkly fortuitous, coming two and a half months after the Nazis invaded Poland. It meant that those paintings, at least, would not be at the gallery the following spring when the Nazis took Paris.

New regime at 21 Rue la Boétie

Edgar Degas, The Dance Lesson, ca. 1879. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Shortly after France signed an armistice with the Nazis on June 22, 1940, the Reich’s ambassador to the Vichy government, Otto Abetz, provided the Gestapo with a list of Jewish art dealers and collectors in Paris. In addition to Paul Rosenberg, the list included his colleagues Jacques Seligmann and Georges Wildenstein. Luckily, when the Nazis arrived at 21 Rue la Boétie, Rosenberg and his family were long gone. They had fled Paris in February 1940, first relocating to a small town near Bordeaux and then, after traveling through Spain and reaching Portugal, landing in New York City on September 20, 1940 (Barr had pleaded with the American authorities to allow the family to enter the country). Of the immediate family, only Rosenberg’s brother Léonce opted to stay in Paris—surviving the occupation, miraculously, only to die in 1947—while Rosenberg’s son Alexandre, 19 at the time, stayed behind in Europe to fight for the Allies.

Meanwhile—aside from the works Rosenberg had sent abroad, a group he’d stored in Tours under his chauffeur’s name, and 162 paintings he’d placed in a bank vault near the southwestern town where the family spent the spring of 1940—the bulk of Rosenberg’s collection, his gallery inventory, and its archive were seized when the Nazis raided 21 Rue la Boétie in July 1940. In September 1941, they also seized the contents of the bank vault. Another 75 works that had remained at the house in the southeast where the family lived in 1940 were also taken. All told, the Nazis looted some 400 paintings belonging to Rosenberg.

But the Nazis’ plans for Rosenberg’s property didn’t end there. They requisitioned 21 Rue la Boétie and, in May 1941, inaugurated the Institut d’Étude des Questions Juives (IEQJ, or Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions) in the former gallery space. The IEQJ was a flagrantly anti-Semitic institution that offered pseudo-scientific propaganda classes on subjects such as “Ethnoraciology” and “Eugenics and Demographics.” Nominally run by the French, the organization was actually under the direct control of Theodor Dannecker, the head of the Gestapo’s Judenreferat. That September, it opened the now-infamous exhibition “The Jew and France” at the Palais Berlitz, whose nationalistic, anti-Semitic exhibits were seen by somewhere between 500,000 and 1 million visitors in Paris before going on a tour of other French cities. For comparison’s sake, MoMA’s “Picasso: Forty Years of His Art” drew just over 100,000 visitors in its 54-day run.

Tracking down the pieces

Paul Cézanne, Bathers, 1892–94. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

On August 27, 1944, two days after the liberation of Paris, members of the Resistance warned the Second Armored Division that one final train of Nazi soldiers and 148 crates full of modern art was about to leave for Germany. Six volunteers and a lieutenant from the Free French forces hurried to hijack the train in the suburbs of Paris, stopping it at Aulnay. That lieutenant was Alexandre Rosenberg, Paul’s son; the last time he’d seen some of the paintings in those crates was on the walls of his parents’ apartment at 21 Rue la Boétie. The heroic episode served as the inspiration for the 1964 Burt Lancaster blockbuster The Train.

Shortly after the liberation, the French government seized 21 Rue la Boétie and, eventually, returned the property to Rosenberg. But as his granddaughter relates in My Grandfather’s Gallery, between the grim uses to which the property had been put under Nazi occupation and the piles of IEQJ propaganda books left behind in its basement, Rosenberg was determined never to live there again. Besides, by then, he had established himself and his gallery in New York. He sold the building in January 1953. Before handing over the keys, he had the four mosaics Braque had made for the gallery floor cut out and turned into tables.

Rosenberg devoted much of his energy in the final 15 years of his life to recovering the art that had been taken from him by the Nazis. Shortly after the war, France’s restitution commission returned the works from the train his son had helped stop, as well as others that had been found stockpiled at Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria. As a gesture of appreciation, Rosenberg donated 33 of them to French museums.

During the years he spent tracking down Nazi loot, his New York gallery, Paul Rosenberg & Company, continued to thrive. After he was demobilized in 1946, Alexandre reunited with his father in the United States and joined the family business, becoming an associate in the gallery in 1952, and then taking its helm when his father died in 1959.

At the time of his death, at age 78, Paul Rosenberg had recovered more than 300 of the works the Nazis had stolen from him. In subsequent decades, his children and other descendants continued to fight for the restitution of his collection. In her 2012 book, Sinclair, his granddaughter, estimated that about 60 of Rosenberg’s paintings were still missing.

Still in the family

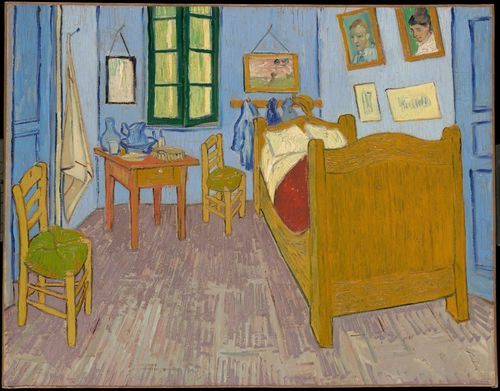

La chambre de Van Gogh à Arles (Van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles), 1889. Vincent van Gogh Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Alexandre continued to run the gallery his father had established on East 79th Street until his death in 1987, when it closed. In 2015, Paul’s granddaughter Marianne Rosenberg revived the family business, launching Rosenberg & Co. on East 66th Street, where it continues the business model that Paul pioneered, offering a mix of contemporary artists and established masters.

From time to time, pieces of the Rosenberg treasure still resurface. In 1998, the family sued the Seattle Art Museum, alleging that a Matisse painting in its collection, Odalisque (1928), had been taken from Rosenberg. The museum commissioned research that confirmed the painting had been among the 162 seized from the bank vault in southwestern France, and in 1999, the museum’s board voted to return it to the Rosenbergs, marking a happy resolution to the first Nazi loot restitution lawsuit filed against a U.S. museum. More recently, in 2014, the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter museum near Oslo returned Matisse’s Profil bleu devant la cheminée (1937) to a member of the Rosenberg family. The following year, another Matisse, Woman with a Fan (1923), which had turned up among the trove seized from Cornelius Gurlitt’s apartment, was returned to the Rosenbergs.

Some works are still being kept from the family, however. In 1987, an Edgar Degas pastel portrait that was taken by the Nazis resurfaced in the inventory of Hamburg-based dealer Mathias Hans. Though the family contacted Hans, he refused to identify the work’s current owner, demanding full payment to restitute the work. For now, that Degas remains out of the Rosenbergs’ reach.

But while some of Paul Rosenberg’s collection remains hidden away, much of it is accessible to his heirs and the wider public through the countless works he gifted to museums or placed with collectors, who, in turn, donated them to institutions. He recalled an encounter with one such piece—now on prominent display at the Art Institute of Chicago—in an unfinished autobiography Sinclair quotes in her book about her grandfather.

“One day when I was about ten, my father led me to the shop window of a dealer who kept a gallery on the rue Le Peletier, to show me a painting that made me shriek with horror,” Rosenberg wrote, describing a painting of a shabby bedroom rendered in “violent colors” with warped walls and dancing furniture. It was one of Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles (1889).

“My father calmed me down and said, ‘I don’t know this artist, and the canvas isn’t signed, but I’m going to find out about him because I’d like to buy some of his paintings,’” Rosenberg continued. “The canvas was by Van Gogh, it’s the one that’s in the Art Institute of Chicago, and which, by an irony of fate, I myself sold about 30 years later.”

from Artsy News

0 notes

Text

Anna Ancher and The Kitchen Maid

“God walks among the pots and pans.” St. Teresa of Avila

Copenhagen

Early Sunday morning. Skies the color of slate, and slate-colored rain pouring down. Late August in Denmark, but as wet and cold as late November in California. Except for a woman in red tennis shoes walking a tiny black dog, there’s not another soul on the streets in Vesterbro while I wait, shivering, for the number 14 bus. Then I’m the only passenger, still shivering, as the bus splashes through the streets to the foggy green and deserted Østre Anlæg Park. Where in the world is everyone this morning? In church? Certainly not in the Hirschprung Museum. Only an elderly couple shares with me the empty galleries. The man and woman appear to be in their late seventies, if not older. They act tenderly toward each other. She is taller, but that’s perhaps because his shoulders are so stooped. Water drips from their gray coats, like water from my black one. Rain pounding on the roof makes it sound like we’re inside a drum.

Gradually a glow of sunlight illuminates us. It’s not a burst of light on the road to Damascus, but still, it’s a revelation. The clouds of Copenhagen have not evaporated, raindrops still rattle down. But here inside the museum light radiates from a small painting; its gravitational field pulls me and the two strangers into its orbit.

The Maid in the Kitchen – Anna Ancher – Oil/canvas – 1883

One of the gifts of museums is that they can nudge us into spaces and times other than the ones we happen to be in — in this case, into northern Europe, into a past none of us are old enough to remember. Another thing: looking at artworks requires patience. Paintings and sculptures insist that, in contrast to the hurry and bustle of the rest of our lives, we need to slow down and pay attention. So let’s pause for a moment with our two elderly companions in front of this painting. What are we looking at here?

A narrow, shadowy kitchen, a partially opened door and the shimmer of sunlight on a wall. Light filters into the room through a yellow curtain. In the foreground there’s a wooden bench with some vegetables. A woman with her back to us works intently, perhaps preparing a meal, perhaps cleaning up the remains of one. Perhaps both.

We can’t see her face or her hands, and the limits of photography don’t permit us to penetrate the shadows around her feet. In the the light of the museum however, her ankles and clogs are clearly revealed. So is her blouse, which in the photograph appears black, but in the painting is an iridescent ultramarine blue–a darker mixture of the same blue that medieval painters used exclusively for the robes of the Virgin Mary.

The countertop itself can stand alone as a masterpiece of light and color that rivals the work of any of the French Impressionists. Look at the pitcher and at the other objects on the sideboard and at the splash of yellow on the wall, then at the cool, blue light coming into the room from the open door, then at the subtle dark stripes near the hem of the maid’s skirt and then at the cool gray shadows beneath the sink. The angle of the bench, with its slightly out-of-focus carrots, cabbages and fish, draws our eyes back into the center of the composition and creates a small still-life masterpiece within this larger masterpiece.

The web of light that envelops the maid in the kitchen and has entranced the three of us in the museum gradually weakens. The elderly couple are visitors from Poland. We don’t share a common language except the gestures of hands and the good will of a smile. We drift apart into other galleries, but an hour later I return alone to encounter the maid in the kitchen once again.

In contrast to well-known French artists of the late 19th century, like Berthe Morisot, the works of Northern European artists, like Anna Ancher (1859-1935) remain largely unknown and neglected by most art historians. The artists have been overlooked because they painted in what were then Scandinavian backwaters, not in France. Women artists in general have been ill-judged because they painted “feminine” subjects– interiors and images of women reading or sewing or tending to the lives of children. And neglected because, as we all know, they were women. (As an artist, I sometimes I think that the world’s biggest blockheads are art historians; that is, until I consider clergymen and politicians.)

But what about the maid? The artist, Anna Ancher, is not well-known, but on the web you can learn something about her life. The maid’s name we will never know. And so I wonder, who was she, and why would Anna Ancher bother to paint her? We can presume that the master and his wife and and their children live in another part of the house. The maid is a servant in the kitchen. Servants have lives too, but most artists ignore them and their lives, with notable exceptions like Vermeer, Chardin and Velázquez. Why? Becase they are women? Mere servants? Why did Anna Ancher paint the maid instead of the master?

It’s a question I wish I could answer. But I thank the painter for making me remember Jane Doherty, born in 1884, a year after this masterwork was painted. She emigrated from the poverty of Northern Ireland to the promise of Western Canada during the early days of the First World War in order to care for the homestead in Alberta that had been established by two of her older emigrant brothers, also drawn to the promise of a better world across the sea. Both of them were killed in the war. Eventually she became my grandmother. As a girl she had worked as a maid, scrubbing dishes and peeling potatoes, the same menial work as the maid in the painting, serving the master and his family. Servant and subservient. Jane did not have an artist to paint her, but at least in Anna Ancher’s painting, her work, the work of maids and the anonymity of their lives, is a reality for us in our hurry and bustle to ponder.

Velázquez would admire this painting; so would Chardin and Berthe Morisot and Vermeer– and the Spanish mystic. As I walked out of the museum into the rain, the Polish couple waved as they got into a taxi. Fog still swirled in deserted Østre Anlæg Park. I turned up my collar and thought: to be touched by Anna Ancher as gently on my damp sleeve as a drop of sunlight–for this I have come to Copenhagen.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2q2sKvs via IFTTT

0 notes