#poetrylectures

Text

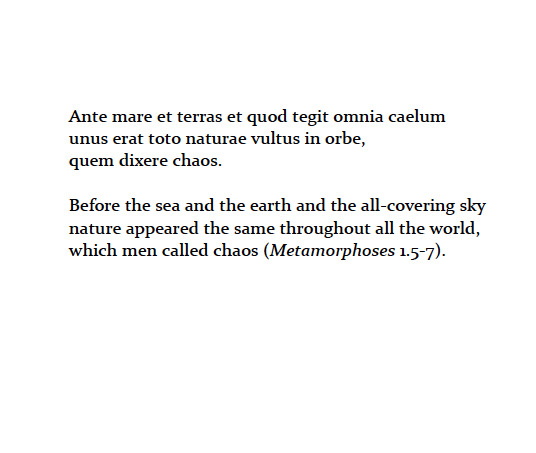

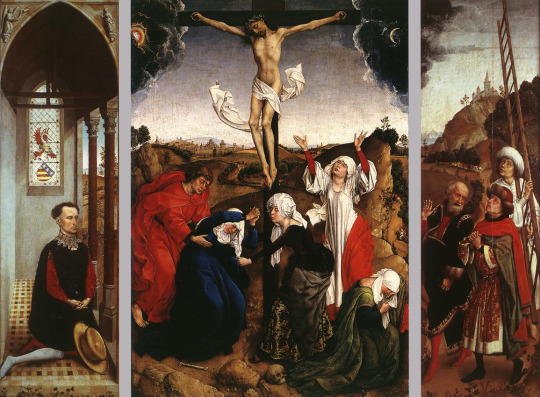

These images are presented in accompaniment with Srikanth Reddy's lecture, "The 'O' of Wonder: A Syzygy," now available to listen to via the BWLS podcast, here.

0 notes

Text

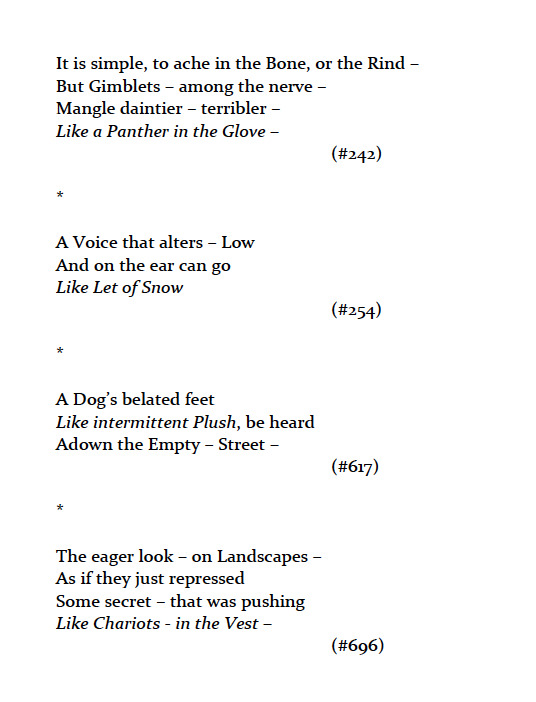

These images are presented in accompaniment with Srikanth Reddy’s lecture, “Like a Very Strange Likeness and Pink,” now available to listen to via the BWLS podcast here.

0 notes

Text

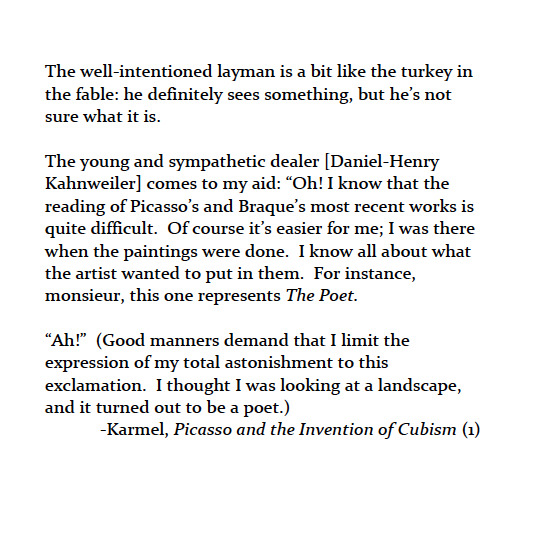

These images are presented in accompaniment with Srikanth Reddy's lecture, "The Unsignificant," now available to listen to via the BWLS podcast here.

0 notes

Photo

The Bagley Wright Lecture Series on Poetry Podcast: Season Five

“You Are Who I’m Talking To: Poetry, Attention, & Audience.” In February of 2018, the BWLS and the University of Arizona Poetry Center co-hosted a three-day conference featuring readings, talks, and conversations between the first six BWLS lecturers: Joshua Beckman, Dorothea Lasky, Timothy Donnelly, Srikanth Reddy, Rachel Zucker, and Terrance Hayes. This season we share recordings of some of the events of those three days, including wide-ranging conversations on poetry and social engagement, practice, autobiography, and non-literary influence.

Listen & subscribe here or wherever you get your podcasts.

#poetrylectures#poetrypodcast#joshuabeckman#dorothealasky#timothydonnelly#srikanthreddy#rachelzucker#terrancehayes

0 notes

Text

from “Writing the Space between the Poem and Prose” by Renee Gladman

In my work, I’m often trying to bring hyper-awareness to the spaces we enter, be they architectural or grammatical. Space is not a container for experience; it is not a waiting plane for our language. The spaces we enter have their own topographies and to cross them is to encounter matter that is already in the field. The white space of the page is electrified before we even approach it. It’s commotional, always moving, always pushing at its borders (borders that exist on many levels: the actual margins of a page, linearity as a border, sense-making as a border, staying within the frame of the poem or the essay or the story as a border). To think is to enter this field. To read, to draw is to enter this field. I like to call all of this writing. The body plus the field is the text, the drawing, the essay, the novel, etc.

To write is to put the body in a present time. Whether we record this activity or not, the body writes in time: as we invent a story or explain a fact or distill an image, the body experiences these acts. The body also sits in a room; perhaps another body or bodies pass as it’s doing this. Perhaps someone calls as the body writes, a message comes in; perhaps the body gets up and looks at a book, sleeps, leaves the room of writing. The body that writes has a nexus inside of it, webs of impulses, details, stories about the world outside of it. Something inside the body moves through the body to get out of the body, and when writing this is done through language, the same language that’s shaping the invented story, or explaining the fact, or distilling the image.

I like the way writing and being a person and moving as a person through space are all synonymous acts. We are always proceeding; we move through the English language in a procession [generally as a subject being put into action toward the making of an event: we make sense when we follow these rules and we establish a certain order to reality.] But I would guess that most writers sense as they are moving along the line of the sentence that there is a lot of activity in the periphery; there are elsewheres emerging perpetually, as if every choice we make when we are writing creates a world of response and inquiry. To write narratively we are encouraged to keep moving, to stay off the grass as it were. Poetry has been more generous; poetry seems to want to build architectures in the grass or of the grass. But, for some of us, when we are in the grass, we miss the road; we want to be on the road and on both sides of the road at the same time. We want to use the road to think about the grass and we want always for there to be grass on the road.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A with Cedar Sigo after his lecture, “A Necessary Darkness: Barbara Guest & The Open Chamber,” at the University of San Francisco, April 24, 2019

Question: Great job on this. Did you see this as relating at all to your archival work around Joanne [Kyger], and what other writers are you going to be lecturing on?

CS: Absolutely. The last lecture I gave before this one was shortly after the death of Joanne Kyger, who I had been working with closely on a book of interviews. She passed away and they asked me to give this lecture, and so I did think of this in relation to Joanne because there are so few women even in that New American Poetry anthology. My next lecture, part of it at least, is about di Prima and Revolutionary Letters, so yeah...why don’t you choose who I write about next? (laughter)

And also, any questions about poetry–it doesn’t have to be about Barbara Guest and Keats and all these famous people.

Q: Can you attempt to describe the process of writing one lecture after another?

CS: I realized for me lecturing is like sifting...I feel like I write and I write and then I go back to it and I cut and I read more and learn more...and then there’s just more ruthless cutting and adding, and then the stuff that you wrote at the very beginning ends up at the very end...you try to scour the few paragraphs left for what ideas are in there that are still useful. It is like writing a gigantic poem in a weird way–it’s less bound to music but the music still clinches the meanings, sometimes. But yeah, it’s just a big mess. But that’s why you need that much support to actually do it! ‘Because it feels as though you can’t have a job and still go that deep. At least I never could. Yeah, so–that’s what it’s been like. It’s been fantastic. I mean, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go deeper than I already was into poetics, but this is just what happened.

Q: I was interested in that quote from Rimbaud’s famous ‘seer’ letter that you included and what you think is at risk in taking on poetry with such an intensity. I forget the exact quote...

CS: Oh yeah, where does he say that? I’ll probably just have to return to the text.... I don’t know how I feel about it in relation to trying to say what he meant, you know, but I did want to say that I used the translation of Paul Schmidt, so all of the stuff that was translated from French was his Rimbaud. Here he says, “You have to be a visionary. Make yourself a visionary. A poet makes himself a visionary through a long, boundless, disorganization of the senses. All forms of love, of suffering, of madness. He searches himself; he exhausts within himself all poisons, and preserves their quintessences.” So to me it sounds like a body falling down a vortex almost? You know what I mean? But you also have the strength to withstand it, and to transform. I think that’s what he’s saying. You know those forms are--hopefully they spring up in the actual poetry. And how much belief is necessary for that to happen. And that’s how he connects to Barbara.

Q: And Rimbaud was sort of a patron saint of the Surrealists and Barbara Guest was so indebted to them...

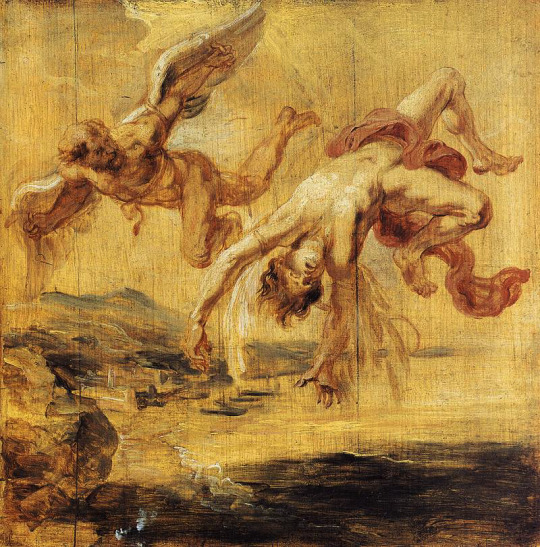

CS: Right, and also, Keats stopped writing because he died so young, He and Rimbaud both both die so young–yeah, I thought of that later, thought maybe I should try to fit this in! They’re soaring over the afterlife, that’s why I say that, their spirits are released, they’re soaring over all this dark terrain–and with her voice–the acoustics and darkness inherent in the voice help create this sensation I think.

Q: About Guest, I know one of the things you said was that in many ways you felt like of the New York School poets, her work holds up the best, for you? And it’s interesting because I’m curious to hear you say a little bit about why that is. Compared to the others, but also: in my experience, Guest is often, I think popularly less well known than the others, and I’m wondering why you think that is.

CS: Well, that’s an easy one! (laughter)

But no, I mean, why was she constantly left out? Why was Joanne left out? Why was Diane di Prima left out, you know? I also want to say that personally all these poets were very sick of having that narrative, too, being imposed on them. I think if you read her work, and I did kind of mention it, she says that “I’ve become less concerned with the work of the 1970s.” And her husband dies and she lives alone in New York for a while and then moves out to Berkeley, I think in the mid-90s, and her style did really change and I think it had to do with a lot of women who were writing in the Bay Area at the time, including Kathleen Frazier, Brenda Hillman, Lyn Hejinian, and the Language Poets penchant for theory, too–and meeting new people, leaving New York, leaving the painters, just making a new life for herself. And I think that is evident in the style. Garrett Caples is trying to claim her as a surrealist in that little memoir section, which I don’t exactly agree with, but there are certainly elements of surrealism in her work. Again, that’s why I think her work is so strong: there are many styles on display. She does have sort of an armory of styles on hand. I love all those poets, and she was closest with Schuyler and Frank. It took years for Ashbery to even blurb her (laughs).

Thank you, Cedar. Let’s have one more round of applause for that.

0 notes