#planters atlantic city

Text

This was a world [...] of breathtaking extremes: on one end were early modern European aristocrats who decorated their salons with sugar sculptures; on the other were millions of enslaved men and women, overwhelmingly of African origin, who were overworked so mercilessly on Caribbean plantations [...].

In the late 1600s, sugar confectioneries were introduced into Siam by a [...] woman of Japanese and Portuguese descent, Marie Guyemar de Pinha [...], who married the king’s Greek prime minister. Two centuries later, a sugar planter like Leonard Wray could effortlessly move between the Malay Peninsula, Natal (in today’s South Africa), and the American South, receiving land in Algeria from Napoleon III and conducting sugar experiments under the auspices of the former governor of South Carolina. Bosma traces the rise of a sugar bourgeoisie in places like Java, the Caribbean, Louisiana, and Brazil that was, by its very definition, transnational. Sugar, after all, constantly required new commodity frontiers as cane monoculture ravaged the soil and turned lush tropical forests into wastelands. Politics and war accelerated this scramble for new frontiers. [After the formal legal abolition of chattel slavery in British territories] [a] man like John Gladstone -- father of British prime minister William -- had to quickly pull up stakes in Demerara (in today’s Guyana) and Jamaica in 1840 and try his luck in deltaic Bengal instead. [...]

Of course, many of those transnational connections were sealed through acts of unspeakable brutality. [...] The workings of the slave-sugar economy [...] guaranteed that the enslaved were reduced to the absolute wretched of the earth [...]. Slaves were shuttled across the Atlantic’s western littoral as new sugar frontiers developed and as European colonies were gained [...]. Saint-Domingue sugar workers might have cast away their chains during the Haitian Revolution, but French planters simply carried those chains across the Windward Passage to Cuba, where they got to work establishing a new, brutal sugar frontier powered by yet more slaves. Equally unsettling, [...] the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834 was followed [...] by the resumption of British mass imports of slave-grown sugar from areas beyond London’s imperial control. Sugar from Brazil and Cuba was simply cheaper, and business and consumer interests trumped any questions of morality. [...] [W]ith massive refinery complexes lining the waterfronts of American and European cities, the commodity remained utterly reliant on slavery, coerced labor, and - in places like Java, where the Dutch designed a system of forced cultivation - suppressed land rights. [...] [G]rossly impoverished workers were cheaper and more easily dispensable. [...] Sugar was only profitable when churned out in mass quantities: consequently, sugar industrialists deliberately overproduced, which artificially drove down prices (and workers’ wages).

---

All text above by: Dinyar Patel. ‘Sugar, Slavery, and Capitalism: On Ulbe Bosma’s “The World of Sugar”’. Published online by LA Review of Books. 9 May 2023. [Some paragraph breaks and contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the vaunted annals of America’s founding, Boston has long been held up as an exemplary “city upon a hill” and the “cradle of liberty” for an independent United States. Wresting this iconic urban center from these misleading, tired clichés, The City-State of Boston highlights Boston’s overlooked past as an autonomous city-state, and in doing so, offers a pathbreaking and brilliant new history of early America. Following Boston’s development over three centuries, Mark Peterson discusses how this self-governing Atlantic trading center began as a refuge from Britain’s Stuart monarchs and how—through its bargain with the slave trade and ratification of the Constitution—it would tragically lose integrity and autonomy as it became incorporated into the greater United States.

Drawing from vast archives, and featuring unfamiliar figures alongside well-known ones, such as John Winthrop, Cotton Mather, and John Adams, Peterson explores Boston’s origins in sixteenth-century utopian ideals, its founding and expansion into the hinterland of New England, and the growth of its distinctive political economy, with ties to the West Indies and southern Europe. By the 1700s, Boston was at full strength, with wide Atlantic trading circuits and cultural ties, both within and beyond Britain’s empire. After the cataclysmic Revolutionary War, “Bostoners” aimed to negotiate a relationship with the American confederation, but through the next century, the new United States unraveled Boston’s regional reign. The fateful decision to ratify the Constitution undercut its power, as Southern planters and slave owners dominated national politics and corroded the city-state’s vision of a common good for all.

Peeling away the layers of myth surrounding a revered city, The City-State of Boston offers a startlingly fresh understanding of America’s history.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early historians of abolition attributed the gradual emancipation laws primarily to the outcome of the Civil War. They argued that Cuban and Brazilian slave-owners embraced reform in large part because the abolition of slavery in North America discredited the institution on the world stage. But many considered this explanation inadequate. In particular, social historians objected to an account of abolition in which enslaved people played almost no part. These scholars developed an alternative explanation for gradual emancipation that was rooted in subaltern agency. In their telling, slave-owners surrendered freedom of the womb as a political concession to their slaves in order to defuse mounting revolutionary tensions within Cuban and Brazilian society.

(...)

Even thousands of miles away, slaves learned of the ‘general strike’ that had begun in the Confederacy. In Brazil, this news first reached the northern province of Maranhão in the fall of 1861. The Union warship the Powhatan docked in the capital city of San Luıís that September, in pursuit of a wayward Confederate cruiser. Within days, Brazilian officials detected a ‘movement’ among the province’s slaves. In towns stretching along the region’s waterways, enslaved Afro-Brazilians had begun to ‘declare their freedom’. Slaves insisted that they ‘no longer had to obey their masters’ because ‘a [US] warship was there to liberate them’.

(...)

For the first time, a number of slave-owners in Cuba and Brazil began to look for a way out. In Brazil, Francisco Antonio Brandão Jr led the way. Brandão was the son of a Brazilian cotton planter, who grew up in the province of Maranhão. For four years, his family had watched plantations across the province go up in flames as fugitive slaves took up arms against the Brazilian government. By 1865, he was convinced that if Brazil failed to abolish slavery, ‘the slave will sign his freedom papers with the blood of his oppressors’. That year, he published A escravatura no Brasil, one of the first major works by an elite Brazilian to call for the gradual abolition of slavery across the empire. In it, he pointed to the black freedom struggle unfolding across the Atlantic World as the central reason that slaves in Brazil were ‘inspired to fight’. Was it necessary, he wondered, for Brazil to pass through the same ‘bloody scenes’ as the United States, before the state would take action?

‘A General Insurrection in the Countries with Slaves’: The US Civil War and the Origins of an Atlantic Revolution, 1861–1866. Samantha Payne, Past & Present 257.1 (2022): 248-279.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 7 - Sunrise is easy to capture if you are anchored out almost as far as you can get in Annapolis Harbor and still be in the harbor.

Morning sunrise in Annapolis

The morning sun gave way to rain. The wind started blowing as well. Molly D’s crew did an excellent job in anchoring yesterday. She stayed put during wind gusts of 23 knots. Three boats near us weren’t so lucky. We watched a sailboat to our left slowly drag its anchor. The boat was unoccupied. Every so often the anchor would catch on the bottom. Then the anchor would free itself and the boat would continue its way out of the harbor. There weren’t any boats that this errant one could ram, so we just watched it creep along. Sooner or later it was going to end up in the shallows and end its drifting. We watched another sailboat drift away. Fortunately, the owner was aboard and managed to start the engine and haul the anchor. I saw the boat anchor in another spot in the harbor. The third boat that dragged its anchor was directly to the left of us. The owners were aboard but it did not phase them that their boat had dragged.

During a lull in the wind and rain we hauled anchor and brought Molly D to the fuel dock. She was a bit thirsty after traveling for nearly a week. Of course, just as we were pulling up to the fuel dock, the rain sprinkle turned into a light rain. Figures.

After fueling, David maneuvered Molly D into a slip at the marina. Tight spot, but he is an excellent boat handler. We weren’t intending to stay at the marina until the last day or so of our stay here in Annapolis. However, there’s something to be said for peace of mind knowing that Molly D is secured at a dock. If we were still at anchor, we’d be worrying about the anchor dragging.

Molly D’s anchoring spot

Molly D’s berth at the marina. Protected from winds and waves

We have been aboard Molly D for nearly a week. With the exception of stepping onto the dock in Atlantic City, we have not had the opportunity to get off the boat and walk. Our feet were truly happy to be in motion once again!

Annapolis is such a fun city to be in. There’s hustle and bustle, many restaurants, historic buildings, and easy to walk streets. Always love coming back.

Seasonal sidewalk planter

View of the harbor from the bridge over Spa Creek

View of the Eastport side of the harbor

Marina in Eastport

0 notes

Text

Halifax police lay two arson charges

Police in Halifax say they have charged a 41-year-old man following two arson incidents that took place in the city Thursday morning.

Around 4 a.m. police responded to a report of a fire in the 5600 block of Spring Garden Road, where police found a planter and an advertising sign on fire.

Police say both blazes were quickly extinguished and a suspect was arrested a short time later.

Allan Robert Patrick is scheduled to appear in Halifax provincial court Thursday to face two counts of arson.

Allegations have not been proven in court.

For more Nova Scotia news visit our dedicated regional page.

from CTV News - Atlantic https://ift.tt/5LHzeVn

0 notes

Text

Planters Peanut Store. On the Boardwalk Atlantic City, NJ c.1950's

1 note

·

View note

Photo

South in the North, North in the South This summer was an exceptional growing season for cowpeas (Vigna ungiculata, the type also produces a well-known white bean with a black eye among other varieties). I grow a few types but speckled graham is the prettiest and most productive with 10 inch pods holding 12-20 tan, purple and gray speckled beans each. Winter started with a freeze last week that knocked out lettuce, broccoli and mustard I hoped to eat with my new year soup. I probably could have saved them had I been home. Ah well, there’s still the whole second half of the cold season and anyway some survived last week. I’ll have cabbages and collards in spring. I hear eating black eye peas and greens on the first day of the new year brings luck. Some say the greens represent paper money, the beans represent coins. I guess, but there is more to historic food technologies than flimsy metaphor. The beans were cultivated in northern Africa and travelled to southeast Asia, back to the Mediterranean, south again to west Africa and over the Atlantic in the 17th Century. They travel well and a big handful can start a small farm. Brassica oleracea is cabbage, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, collards, broccolini, romanesco, kohlrabi, tree kale and that decorative purple and white cabbage looking thing that’s in every sidewalk planter in the city in winter. That technology was developed in the Mediterranean and perfected in both Asia and northern Europe. A plant with a broad phenotype and tiny seeds, a handful is enough to start a small farm. These well-travelled ingredients have roots here, sure, but even deeper roots elsewhere in multiple diasporas. It’s a way to eat history, to remember ancestors who traveled by force, and to think about shared, overlapping histories. Like art they represent human innovation, care for an idea over eons, a connection to the past & a promise to the future. 1 Jodi Hays and 2 Michi Meko from their show at Susan Inglett. 3, Eggleston. 4, Marshal mocking nauman, recalling Igbo Landing and water deity myths. 5, Bklyn favorite Rico Gaston. 6, McCarthy. 7, 8 Peter Williams. 9, a bed of dead mustard greens, 10 soaking beans.

0 notes

Photo

Real Historical Women in Fiction: Book Recs

Island Queen by Vanessa Riley

A remarkable, sweeping historical novel based on the incredible true life story of Dorothy Kirwan Thomas, a free woman of color who rose from slavery to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful landowners in the colonial West Indies.

Born into slavery on the tiny Caribbean island of Montserrat, Doll bought her freedom—and that of her sister and her mother—from her Irish planter father and built a legacy of wealth and power as an entrepreneur, merchant, hotelier, and planter that extended from the marketplaces and sugar plantations of Dominica and Barbados to a glittering luxury hotel in Demerara on the South American continent.

Vanessa Riley’s novel brings Doll to vivid life as she rises above the harsh realities of slavery and colonialism by working the system and leveraging the competing attentions of the men in her life: a restless shipping merchant, Joseph Thomas; a wealthy planter hiding a secret, John Coseveldt Cells; and a roguish naval captain who will later become King William IV of England.

From the bustling port cities of the West Indies to the forbidding drawing rooms of London’s elite, Island Queen is a sweeping epic of an adventurer and a survivor who answered to no one but herself as she rose to power and autonomy against all odds, defying rigid eighteenth-century morality and the oppression of women as well as people of color. It is an unforgettable portrait of a true larger-than-life woman who made her mark on history.

Lost Roses by Martha Hall Kelly

It is 1914 and the world has been on the brink of war so many times, many New Yorkers treat the subject with only passing interest. Eliza Ferriday is thrilled to be traveling to St. Petersburg with Sofya Streshnayva, a cousin of the Romanov's. The two met years ago one summer in Paris and became close confidantes. Now Eliza embarks on the trip of a lifetime, home with Sofya to see the splendors of Russia. But when Austria declares war on Serbia and Russia's Imperial dynasty begins to fall, Eliza escapes back to America, while Sofya and her family flee to their country estate. In need of domestic help, they hire the local fortuneteller's daughter, Varinka, unknowingly bringing intense danger into their household. On the other side of the Atlantic, Eliza is doing her part to help the White Russian families find safety as they escape the revolution. But when Sofya's letters suddenly stop coming she fears the worst for her best friend.

From the turbulent streets of St. Petersburg to the avenues of Paris and the society of fallen Russian emigre's who live there, the lives of Eliza, Sofya, and Varinka will intersect in profound ways, taking readers on a breathtaking ride through a momentous time in history.

Enchantress of Numbers by Jennifer Chiaverini

The only legitimate child of Lord Byron, the most brilliant, revered, and scandalous of the Romantic poets, Ada was destined for fame long before her birth. Estranged from Ada’s father, who was infamously “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” Ada’s mathematician mother is determined to save her only child from her perilous Byron heritage. Banishing fairy tales and make-believe from the nursery, Ada’s mother provides her daughter with a rigorous education grounded in mathematics and science. Any troubling spark of imagination—or worse yet, passion or poetry—is promptly extinguished. Or so her mother believes.

When Ada is introduced into London society as a highly eligible young heiress, she at last discovers the intellectual and social circles she has craved all her life. Little does she realize that her delightful new friendship with inventor Charles Babbage—brilliant, charming, and occasionally curmudgeonly—will shape her destiny. Intrigued by the prototype of his first calculating machine, the Difference Engine, and enthralled by the plans for his even more advanced Analytical Engine, Ada resolves to help Babbage realize his extraordinary vision, unique in her understanding of how his invention could transform the world. All the while, she passionately studies mathematics—ignoring skeptics who consider it an unusual, even unhealthy pursuit for a woman—falls in love, discovers the shocking secrets behind her parents’ estrangement, and comes to terms with the unquenchable fire of her imagination.

The Dream Lover: A Novel of George Sand by Elizabeth Berg

A passionate and powerful novel based on the scandalous life of the French novelist George Sand, her famous lovers, untraditional Parisian lifestyle, and bestselling novels in Paris during the 1830s and 40s. This major departure for bestseller Berg is for readers of Nancy Horan and Elizabeth Gilbert.

George Sand was a 19th century French novelist known not only for her novels but even more for her scandalous behavior. After leaving her estranged husband, Sand moved to Paris where she wrote, wore men’s clothing, smoked cigars, and had love affairs with famous men and an actress named Marie. In an era of incredible artistic talent, Sand was the most famous female writer of her time. Her lovers and friends included Frederic Chopin, Gustave Flaubert, Franz Liszt, Eugene Delacroix, Victor Hugo, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and more. In a major departure, Elizabeth Berg has created a gorgeous novel about the life of George Sand, written in luminous prose, with exquisite insight into the heart and mind of a woman who was considered the most passionate and gifted genius of her time.

#fiction#history#historical fiction#historical#historical reads#womens history#women in history#to read#Book Recommendations#reading recommendations#booklr#reading list#book list#library#summer reading#cool books#book covers

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capitalism & Racism in Black Sails

In order to properly understand the individual and collective responses to England’s empire in Black Sails, it is necessary to understand capitalism and its relationship to racism. What follows are my thoughts on the relationship between capitalism and racism (focusing on the late 1600s/the development of capitalist England), and how those things relate to the show. It’s a long post, but by no means is it an exhaustive analysis of either capitalism or Black Sails, so I look forward to what others have to say on the subject!

First, what is meant by “capitalism”?

Capitalism describes an economic system in which private businesses own the means of production––the materials and tools used in the production of goods. This system creates distinct classes within society: the bourgeoisie who own the corporations and the proletariat who must work at these corporations and thereby become subservient to the bourgeoisie.

Explained in Ellen Meiksins Wood’s The Origin of Capitalism, capitalism emerged most specifically in England as a result of the agrarian feudal creation of the landlord-tenant relationship, in which the landlord rented land to the tennant, who was incentivized to produce as many goods as possible. This system led to the complete privatization of land and the creation of wage-laborers who could not produce enough goods to themselves become part of the bourgeoisie. Over time, as these wage-laborers became more numerous, society shifted from being agrarian-centered to revolving around the creation of cities to facilitate the mass production of goods.

How is capitalism tied to racism?

The spread of early capitalism throughout Europe was facilitated by improvements in technology allowing for the mass production of goods from raw materials. Capitalist countries thus turned outward in search of raw goods to power their economies. As Marx explains in Capital:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the indigenous population of that continent, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of blackskins, are all things which characterise the dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive accumulation. On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre (Chapter 31).

Capitalism thus rests on the idea of “primitive accumulation,” that being the initial expropriation of the individual from the land, achieved through feudalism domestically and chattel slavery internationally. Because capitalism demands the constant mass production of goods, it requires increasing volumes of raw goods––sugarcane, cotton, coffee beans, etc.––which are obtained through the extension of colonialist enterprises in order to keep parts of the world in a continuous state of underdevelopment.

Although pre-capitalist societies had slaves, the advent of capitalism necessitated slavery on a mass scale, produced through the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, in which indigenous populations were wiped out and replaced with slave laborers. This system resulted in complete alienation of labor as white laborers in the “New World” were replaced by the early 1700s with more ‘cost-effective’ enslaved Africans who had no ties to their owners or to the land they worked. As former Trinidadian Prime Minister Eric Williams put it:

Here, then, is the origin of Negro slavery. The reason was economic, not racial; it had to do not with the color of the laborer, but the cheapness of the labor. [The planter] would have gone to the moon, if necessary, for labor. Africa was nearer than the moon, nearer too than the more populous countries of India and China. But their turn would soon come” (14).

Racism, then, is indistinguishable from the power structures of capitalism. The desire of the bourgeoisie to increase their capital led to the creation of the slave trade in order to accumulate mass volumes of raw goods so their proletariat workers could transform them into goods to then be sold back to the workers for profit.

This system thus creates two types of exploitation: the exploitation of the enslaved people and colonized lands, as well as the exploitation of the domestic working class. The need to keep this system in place demanded capitalist societies craft the false belief in white supremacy in order to justify the enslavement of Africans, Indians, and various Indigenous peoples in Asia and Latin America.

So, how does piracy come into the picture?

In the mid-late 1600s, England began its industrial revolution, propelling the island to increase its Atlantic trade. This desire to trade created a new merchant class, expanded the number of laborers in American colonies, and launched England into various wars with competing European powers. In Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age, Marcus Rediker describes the social conditions of this era thusly:

By 1716, big planters drove armies of servants and slaves as they expanded their power from their own lands to colonial and finally national legislatures. Atlantic empires mobilized labor power on a new and unprecedented scale, largely through the strategic use of violence––the violence of land seizure, of expropriating agrarian workers, of the Middle Passage, of exploitation through labor discipline, and of punishment (often in the form of death) against those who dared resist the colonial order of things. By all accounts, by 1713, the Atlantic economy had reached a new stage of maturity, stability, and profitability. The growing riches of the few depended on the growing misery of the many.

Piracy emerged from this poverty in England and in its colonies, as poor people who knew how to sail figured they had little to lose and much to gain in turning to piracy. Moreover, piracy offered an alternative to the oppressive nature of living under England’s empire. Pirate ships “limited the authority of the captain, resisted many of the practices of capitalist merchant shipping industry, and maintained a multicultural, multiracial, and multinational social order.” On these ships, pirates learned “the importance of equality…[their] core values were collectivism, anti-authoritarianism, and egalitarianism, all of which were summarized in the sentence frequently uttered by rebellious sailors: “they were one & all resolved to stand by one another.” In Marxist terms, pirates retained control over the means of production and their labor, producing a more egalitarian division of profit in which all received the same share.

The Golden Age of Piracy, then, emerged in response to England’s adoption of capitalism. Despite the threat of death, exploited workers turned to piracy out of desperation and the quest for securing immediate wealth. Although piracy was often violent, it nonetheless embodied a system of labor in stark contrast to that of capitalism, based not on unequal acquisition of goods but on the fundamental equality of human beings.

How does this capitalist context enrich our understanding of Black Sails?

England’s capitalist-driven empire provides the system under which all of our characters struggle and thus informs their every decision. The characters’ backstories we are given all pertain to their desire to either escape from capitalism or assimilate with it. As this post is quite lengthy, I won’t go into detail about every single character, only the ones who most illustrate the manner in which capitalism operates.

First, James Flint’s backstory is not simply that of a man who experienced homophobia and wants revenge for it. We learn of him that his father was a carpenter and he was raised by his grandfather in Padstow, a working-class fishing town in north Cornwall. Because of this, he was barred from receiving a formal education and likely joined the navy because it offered him the opportunity for some sort of upward mobility, though it’s clear in his interactions with his peers that they will never see him as an equal due to his lower-class status. The manner in which James’s peers treat him very likely plays a role in his decision to support Thomas’s plan for Nassau. Despite the plan still being colonialist, it did seek to undermine a key component of capitalism: the dehumanization of the working force. This dehumanization is a fundamental element of capitalism (and this empire) because if laborers believe they have inherent worth, they are more likely to challenge the bourgeoisie. Thus, James’s exile from England was not because he was gay, but because he sought to undercut the foundations of England’s wealth, a choice driven by his love for Thomas and his own relationship to capitalism.

Connected to Flint’s backstory is Billy’s, as it also involves the navy. From the mid-1600s to the early 1800s, Britain relied on the practice of impressment––forcing people to serve in the navy––to advance its colonial aims. Billy’s parents were levellers, people who opposed impressment. As punishment for this, Billy was taken as a child and forced into “press gangs” and served in the Navy for three years as a bonded laborer (the naval equivalent of debtors’ prison) until his ship was captured by Flint and he was given the opportunity to join the crew after killing his captor. Like Flint, then, Billy became a pirate as a direct result of the violence done to him by capitalist-imperialist England.

Likewise, Jack became a pirate as a consequence of English capitalist industrialization. His family had for generations owned a tailoring business, but it was driven out of business by the creation of a massive textile mill. After his father died, Jack was forced to assume responsibility for his father’s debts, which he would work off as an indentured servant at the very textile mill responsible for the debt. Jack, then, turns to piracy to escape capitalism.

To understand the backstories of Flint, Billy, and Jack, you must understand the process by which England assumed a capitalist economy and how that shift from feudalism to capitalism affected both domestic and international practices in the early 1700s. The introduction of distinct classes based on relationships to labor mandated strict inequality and the valuation of mass production at the expense of individual lives.

How does Black Sails depict the relationship between racism and capitalism?

The most obvious answer here is the show’s involvement of Madi and the Maroons, who exist solely as a result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Because this is already a lengthy post, I would like to set Madi aside in order to talk about Max, who I think offers a less overt critique of what Cedric Robinson calls “racial capitalism.”

Max, rather than seeking to run from capitalism, wants to become a member of the bourgeoisie. Her enslavement is, of course, the result of French colonialism in the Caribbean, but rather than recoil from civilization, her enslavement propels her to want to join it. As she tells Anne:

“When I was very small, I would sneak out of the slave quarters at night to the main house. I would stand outside the window to the parlor. I would stand amongst the heat and the bugs and the filth on my toes to see inside. Inside that house was a little girl my age… With the most beautiful skin. I watched her dance while her father played music and her mother sewed. I watched her read and eat and sing and sleep, kept safe and warm and clean by her father. My father. The things it took to make that room possible, they were awful things. But inside that room was peace. That is what home is to me” (3.3).

She reiterates this understanding of society to Marion Guthrie when she states that “progress cannot begin and suffering will not end until someone has the courage to go out into the woods and drown the damned cat” (4.07). While she recognizes the evils of civilization, she also believes that it offers comforts for the select few, and she wants to be one among the few.

Max, indeed, is successful in assimilating into capitalist society. She works her way out of sex work until she owns most of Nassau, not once but twice. This achievement initially seems like a massive success and proof in the viability of Max’s methods, but in subtle ways, the show demonstrates that assimilation is not liberation.

Because, as Ibram X. Kendi stated, “The life of racism cannot be separated from the life of capitalism,” Max’s attempts to assimilate come with the betrayal of the rest of the enslaved people. Although she herself refuses to use slave labor, her treaty with Mrs. Guthrie, Silver, and the Maroons requires the Maroons to return escaped Black people into slavery. Moreover, she has won herself power in a system that refuses to recognize her presence, forcing her to pretend that Featherstone is the real governor of Nassau.

Further, her assimilation into the capitalist system alienates her from other Black people. The two characters with whom she is most closely associated with are Anne and Eleanor, white women whose whiteness affords them a certain level of protection not offered to Max. She never interacts with Madi or any of Madi’s people and she therefore cannot comprehend any other path but assimilation.

For all of Max’s efforts to learn from Eleanor and do better than Eleanor in running Nassau, she ends up in virtually the same place as Eleanor, but even more hidden. The Guthrie family still holds financial control of Nassau, Woodes Rogers still looms in the distance, and though piracy exists, it is even less acceptable. Thus, while Max is often credited as the person who most “sees life as it is,” her alienation under capitalism prevents her from seeing life “as it should be.”

Conclusion

As capitalism emerged as the dominant economic and political system beginning in the early 1700s, it came to define all aspects of global society, down to the very relationships people had with each other. It is impossible, then, to truly understand the motivations of anyone in the show without discussing their relationship to capitalism. This is by no means an exhaustive account of Black Sails’ commentary on capitalism and racism (I didn’t even mention Vane’s conversation with the Spanish soldier), but it hopefully underscores the idea that knowledge of capitalism (and therefore imperialism) is essential for fully comprehending the show.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Pierrot Jacket and the Pursuit of French Fashion in the Americas

I've decided to start a new project in which I take historical pieces I've made, select one element, and expand upon that element's greater historical context...For me, pierrot jackets are the quintessential French style of the late 18th century and I'm based in the US, so I decided to do a reflection on French fashion in the Americas, specifically French colonies, and how it was intertwined with French women's enslavement and control of Black women.

Most of the information in this post is from Karol K. Weaver's "Fashioning Freedom: Slave Seamstresses in the Atlantic World.

What does it mean to wear French fashions in the western hemisphere? Enslavers, planters, and merchants in St. Domingue, both French-born and Creole, pursued French fashion even as the hot climate and the innovations of free women of color created unique styles. Their pursuit of fashion was facilitated by the enslavement of Black men and women, both in the wealth produced by plantations and the labor of enslaved seamstresses.

Like in British colonies, French colonists purchased goods from the mother country, including the means to create fashionable dress. In the March 28, 1768 edition of Les Affiches Americaines , Saint Domingue's newspaper, a tailor named Brohan placed a notice in among the advertisements for plantations and enslaved men and women (vol 12. p100-3). Brohan was fresh from Paris, and he offered dressing gowns, ribbons, hats, thread, and silk, among various other items.

French women attempted to enforce their stylistic supremacy within St. Domingue, even as they appropriated Black fashions, by pressuring officials to restrict the types of dress that free women of color could wear, such as mandating headscarves and forbidding silk (Weaver 51). French fashions became a tool for white colonists to enforce a visual system of inferiority when they felt threatened by the prominence of free women of color.

Some enslavers even sent or brought their enslaved seamstresses to France in order to learn French fashions and methods (Weaver 48). By doing so, French women of the Caribbean actively used their slave-owning status as a way to increase their connection to the French mainland. Their aspirations to French elite status and fashioning was inextricable from their enslavement of Black women.

Enslaved men and women brought to France during the 18th century had the opportunity to sue for freedom when they arrived on French soil (Peabody 6-7). They might also be manumitted, as enslavers attempted to retain their services rather than let them be sent back to the colonies by French officials (Peabody 135). Enslaved seamstresses brought to France could therefore force their own freedom, subverting their mistresses' attempts to enhance their own status as fashionable elite slaveowners.

Enslaved seamstresses and laundresses who remained in French colonies took revenge where they could. A French mistress’s fine wardrobe could be continually marred by torn fabric, missing buttons, and other injuries--the “accidents” from enslaved women’s washing and ironing (Weaver 54). Seamstresses could self-liberate themselves and run away, using their skills to support themselves in urban centers among other free women of color (Weaver 54).

The presence of French fashion in the Americas was coupled with the exploitation of enslaved individuals. French women in the colonial Caribbean sent their enslaved seamstresses to train in cities in the colonies or France itself. Colonial women further used style as a way to mark themselves as a way to mark themselves as superior by reserving certain elements of dress for whites only. Despite this, their pursuit of fashion enabled enslaved seamstresses to assert their own power, either by taking their own freedom or sabotaging their mistresses' clothing.

Works cited:

Les Affiches Americaines 1768, Vol. 12 Page 100-3 University of Florida Digital Collections, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00000449/00004/104j

Peabody, Sue. There Are No Slaves in France: The Political Culture of Race and Slavery in the Ancien Régime. New York: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1996.

Weaver, Karol K. "Fashioning Freedom: Slave Seamstresses in the Atlantic World." Journal of Women's History 24, no. 1 (Spring, 2012): 44-59.

Further reading:

Potofsky, A. "Paris-on-the-Atlantic from the Old Regime to the Revolution." French History 25.1 (2011): 89-107

Skeehan, Danielle C. "Caribbean Women, Creole Fashioning, and the Fabric of Black Atlantic Writing." The Eighteenth Century 56, no. 1 (2015): 105-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24575132.

#costume history#fashion history#historical costuming#my costumes#colonial history#historical sewing

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knowing that the difference between profit and loss might well be a matter of whether or not they complied with the Navigation Acts, Beekman and his correspondents didn’t scruple at evasive measures—bribing customs collectors, doctoring ships’ manifests, circulating fraudulent bond certificates, and outright smuggling. After Parliament passed the Molasses Act in 1733, such conduct became almost a way of life. Planters on Guadeloupe, Martinique, and other islands of the French West Indies responded to the law by offering premium prices for North American provisions and asking less for sugar and molasses than did their British counterparts. When it became evident that customs officials were making only halfhearted attempts at enforcement, the profitability of illicit trade for North American merchants was assured. (It may have accounted for one-third of all northern commerce.) Beekman himself became so accustomed to smuggling that he would complain bitterly if circumstances compelled him to pay full duty on the rum and molasses he imported by way of Rhode Island.

What Beekman and men like him almost never did was invest their profits in plantations. Trade, not production, was the New Yorkers’ forte, and they tended to think of the West Indian plutocracy as wildly dissolute and irresponsible. Nor did more than a handful of them engage in direct trade with England. Local products alone couldn’t fetch high enough prices in the mother country to pay for imported manufactures. Also, because the prevailing winds blew out of the west, getting back to New York from, say, Bristol or Liverpool was a hazardous and time-consuming proposition. Ships outward bound from British ports usually took tropical routes to the New World, dropping down to Madeira to catch the Canaries Current, then winging across to the West Indies and working up the North American coast. Over time, improvements in ship rigging and design—the appearance of the gaff-rigged “schooner,” the development of jib and headsails, and the adoption of the helm wheel—gradually made it easier to sail in the teeth of the westerlies. Even then, however, the majority of New York merchants continued to concentrate on the West Indies and other North American colonies.

The net result was the economic triangulation of three strikingly different systems of production: the small-farm hinterlands of northern seaports, the slave-labor plantations of the Caribbean, and the wage-labor workshops of early industrial England. New York now lived by feeding the slaves who made the sugar that fed the workers who made the clothes and other finished wares that New Yorkers didn’t make for themselves. Along the way, they closed in on their old objective of breaking Boston’s grip on the economies of southern New England. Lying a week closer to Barbados and ten days closer to Jamaica, the city enjoyed a natural advantage over Boston in competition for the lucrative West Indian markets. Inexorably, pressed by Philadelphia’s domination of the mid-Atlantic region, New York merchants took control of the New England coasting trade.

— Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (1998)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, it is critical to acknowledge the centrality of Britain to the world economy in order to understand how Chinese and Indian tea fitted into it. [...] Asian tea relied on forms of employment [...] such as independent family farms in China and indentured ‘coolies’ in India. [...] It would be very difficult to explain how and why Asian tea became driven by the modern dynamics of accumulation then, unless we connect China and India to the broader global division of labor, centered on the most cutting-edge industrial sectors in the north Atlantic. [...] But I also wish to reframe the idea of British capital as “protagonist,” because when we think about capital, agency is a weird thing. [...] Nothing about accumulation is inherently loyal to this or that region, though it has been concentrated in certain sites, such as nineteenth-century Britain or twentieth-century US, and it has been territorialized by nationalist institutions. Thus, although British firms drove the Asian tea trade at first, by the twentieth century Indian and Chinese nationalists alike protested British capital [...].

Most economic histories were focused on whether other countries could ever develop into nineteenth-century England. For labor historians, Mike Davis recently wrote, the “classical proletariat” was the working classes of the North Atlantic from 1838-1921. These modular assumptions jump out when you flip through the classics of Asian economic and labor history, almost always focused on some sort of textile industry (silk, cotton, jute) and in cities such as Shanghai, Osaka, Bombay, Calcutta. By contrast, I was really inspired by a field pioneered by South Asia scholars known as “global labor history” — especially the work of Jairus Banaji — which has been critical of the centrality of urban industry in economic history. Instead, these scholars reconsider labor in light of our current world of late capitalism, including transportation workers, agrarian families, servants, and unfree and coerced labor. These activities have enabled global capitalism to function smoothly for centuries but were overlooked because they did not share the spectacular novelty of the steam-powered factories of urban Europe, US, and Japan.

As far as how tea production worked: in simple terms, Chinese tea was a segmented trade and Indian tea was centralized in plantations known as ‘tea gardens.’ The Chinese trade relied on independent family farms, workshops in market towns, and porters ferrying tea to the coastal ports: Guangzhou (Canton) then later Fuzhou and Shanghai. By contrast, British officials and planters built Indian tea from scratch in Assam, which had not been nearly as commercialized as coastal China or Bengal. They first tried to replicate the ‘natural’ Chinese model of local agriculture and trade, but frustrated British planters ultimately decided to undertake all of the tasks themselves, from clearing the land to packaging the finished leaves. [...] Indian tea was championed as futuristic and mechanized. [...]

In India [...] the tea industry’s penal labor contract became one of the original cause célèbres of the nationalist movement in the 1880s. The plantations later became a site for strikes and hartals, the most famous occurring in the Chargola Valley in 1921. But even though tea workers chanted, “Gandhi Maharaj ki jai” at the time, Gandhi himself had allegedly visited Assam and declined to see the workers, meeting instead with British planters to assure them they were safe. While Indian nationalists had politicized indenture in Assam tea, their main complaint was the racialized split between British capital and Indian labor. Their remedy was not to liquidate the tea gardens but to diversify ownership over them. The cause of labor was subordinated to the nationalist struggle.

---

Words of Andrew B. Liu. As interviewed by Mark Frazier. Transcript published as “Andrew B. Liu - Tea War: A History of Capitalism in China and India.” Published online by India China Institute. 23 March 2020. [Some paragraph breaks and contractions added by me.]

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

MULLATO

1940

Mulatto is a play by Langston Hughes. It premiered on Broadway in 1935 moving theatres five times before closing with a run of 373 performances. Until Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin In The Sun opened in 1959, the play held the record for the longest running Broadway production by an African-American.

The title refers to a person of mixed white and black ancestry, especially a person with one white and one black parent.

The play takes place in the living room of a Plantation near Cedartown, Georgia.

Brooks Atkinson described it as:

a sobering sensation

One Philadelphia newspaper explained it as:

A melodrama of miscegenation in the South telling the story of a wealthy Southern planter who philanders with his housekeeper and sends his four Mulatto children North to be educated. The Yankee environment instills in them the spirit of equality, so that when they return to the plantation they antagonize their family and neighbors.

Advertisements promised:

a darling drama of sex life in the South.

Despite its Broadway success, the City of Brotherly Love had no love for Mulatto. It was banned not once, but twice when attempting to tour through the city. A third attempt at a production in February 1940 met with the same results.

The instigator of the original ban, Mayor S. David Wilson, claimed that the play would incite riots, despite the fact that not once during Mulatto’s 373 performances in New York, or its three month-run in Chicago, did it stir even the hint of a riot. “The show won’t go on,” declared the mayor, claiming Mulatto was “an outrageous affront to decency.” He was particularly aggrieved that the play dared to open during the Lenten season!

Mulatto producer Jack Linder assured the mayor and the press that “many changes had been made and the objectionable features had been removed. The author, however, was not consulted.

One critic wondered whether enough “soap and water has been applied to make it safe for Philadelphia consumption.” Wilson stuck to his decision and posted police at the entrances of the darkened theater.

Philadelphia wasn’t the only town deprived of Mulatto. Baltimore also banned the play, piggy-backing on Philadelphia’s censorship. Somewhat ironically, today Northern Baltimore contains a neighborhood known as Langston Hughes.

Mulatto found audiences elsewhere, as close as the Garden Pier Theatre in Atlantic City, the following August. Although Atlantic City (and New Jersey at large) was historically more liberal than its Liberty Bell neighbor, black beach-goers were still restricted to a strip of sand referred to as Chicken Bone Beach. Perhaps coincidentally, Hughes’ autobiography was published the same year (1940) that Mulatto played the pier. It was titled Big Sea.

The cast for this production included Miriam Battista, Stuart Beebe, Abbie Mitchell, Harry Hanlon, Edwin Forsberg, Hurst Amyx, and George Rathbone. In addition to Atlantic City, it also played Brooklyn’s Flatbush Theatre, where it was billed as a “SEXational drama.”

Ten years earlier, Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston collaborated on a play titled Mule Bone, with Hughes writing in Westfield NJ. The play was to be produced in Atlantic City, Asbury Park, Philadelphia, and other locations, but the authors had a falling out over copyright and it wasn’t staged until 1991.

Around 1929, Hughes’ mother Carrie, his stepfather and stepbrother, lived in Atlantic City. Hughes visited for holidays. Atlantic City was notably mentioned in Hughes’ 1922 poem “Brass Spittoons”:

Clean the spittoons, boy.

Detroit,

Chicago,

Atlantic City,

Palm Beach.

Clean the spittoons.

Even more pointedly in 1947′s “Seashore Through Dark Glasses”:

Atlantic City

Beige sailors with large noses

Binocular the Atlantic...

At Club Harlem it's eleven

And seven cats go frantic.

Two parties from Philadelphia

Dignify the place

And murmur.

Such Negroes

disgrace the race!

On Artic Avenue

Sea food joints

Scent salty-colored

Compass points.

Club Harlem was a nightclub at 32 Kentucky Avenue in Atlantic City. Founded in 1935, it was the city's premier club for black jazz performers. It closed for good in 1986 and was torn down after storm damage in 1992. It was one of the filming locations for the 1980 film Atlantic City. And let’s remember, too, that Harlem is an Americanization of Haarlem.

Hughes misspells Arctic Avenue, but the address is well known for being a property in the board game Monopoly. To be fair, Monopoly itself misspells Marven Gardens, which is a contraction of MARgate and VENtnor, the two towns that make up the island where Atlantic City sits.

After Wilson’s death of, the play’s producers attempted again to bring Mulatto to the Philadelphia stage. But Wilson’s successor invoked the earlier decision and debate continued. Wilson’s censorship stood. Langston Hughes’ Mulatto has yet to have its Philadelphia premiere. The closest it has come was a high school production in Chester PA, 20 miles from Philly, in 1970.

In 1947, there were international productions of the play in both Italy and Brazil.

In November 1950, a musicalization of the play titled The Barrier played on Broadway for just four performances. The brief run essentially tabled any discussion of the musical playing Atlantic City, Philadelphia - or any other city.

#Mulatto#Langston Hughes#Atlantic City#Garden Pier#Broadway#Broadway Play#Black HIstory#The Barrier#Theatre#Play#Philadelphia#banned#canceled

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vampr Erik Origin

Okay so let me make a disclaimer:

I had to do a lot of research to try and create his back story in summary form. I basically learned a lot of shit that I didn’t know so with that being said, you guys can feel free to fact check me because I feel like this needs to be factual as far as the history of it goes. Also, Erik was born/reborn in an era that is very touchy. I mean, we go through crap as black people everyday but I used some very degrading words to represent how it was back in this time. If this is offensive, please feel free to let me know I will change it. I don’t want to offend or make anyone feel bad. So, here it is! This is the origin I came up with.

Erik Stevens is his alias but he was born Ricardo Dupoux. Erik was born in 1856 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Just 29 years before he became a vampire.

Erik’s mother was born in 1836. Her name was Fabiola Adonis and she is from Louisiana but her parents and family (Erik’s grandparents) are from Sainte-Dominigue which is now known as Haiti.

Erik’s father was named Jacques Dupoux. He was born in 1827 in Cuba and he migrated to Louisiana with his family when he was just four years old.

Both sides of Erik’s family originated in Sainte-Dominigue and began to migrate out during the black Haitian Revolution as free people of color. The Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on 22 August 1791, and ended in 1804 with the former colony's independence. It involved blacks, mulattoes, French, Spanish, and British participants—with the ex-slave Toussaint Louverture emerging as Haiti's most charismatic hero. The revolution was the only slave uprising that led to the founding of a state which was both free from slavery, and ruled by non-whites and former captives. It is now widely seen as a defining moment in the history of the Atlantic World.

Haitian Vodou, is an Afro-American religion that developed in Afro-Haitian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional religions of West Africa and the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. Vodou is an oral tradition practiced by extended families that inherit familial spirits, along with the necessary devotional practices, from their elders. In the cities, local hierarchies of priestesses or priests (manbo and oungan), “children of the spirits” (ounsi), and ritual drummers (ountògi) comprise more formal “societies” or “congregations” (sosyete). In these congregations, knowledge is passed on through a ritual of initiation (kanzo) in which the body becomes the site of spiritual transformation. Many Vodou practitioners were involved in the Haitian Revolution which overthrew the French colonial government, abolished slavery, and formed modern Haiti. The Roman Catholic Church left for several decades following the Revolution, allowing Vodou to become Haiti's dominant religion. They referred to themselves as “serving the spirits” more so than using Voudou to refer to Haitian religion.

Jacques Doupoux and Fabiola Adonis were well respected within the Vodou community. Erik’s father was a hounsi bosale and Artisan. Hounsi is essentially a dedicated member of Vodou, an apprentice of priests. His mother, Fabiola, an Ounsi, oversaw the liturgical singing and shaking the chacha rattle which is used to control the rhythm during ceremonies. She had a voice that used to lull Erik to sleep. Jacques wanted Erik to follow in his footsteps and later become an oungan; a Vodou priest. He was born as a “child of the house” or a pititt-caye. Being an oungan provides an individual with both social status and material profit. Erik was present for his father's initiation when he was just a baby with his mother in a shared Ounfò; Vodou temple. There were four levels of initiation that Jacques Doupoux went through. That sealed Erik’s future.

The Ounfò was a basic shack in Bayou St. John. The main ceremonial space within the Ounfò is known as the peristil. brightly painted posts hold up the roof, which is often made of corrugated iron but sometimes thatched. The central one of these posts is the poto mitan or poteau mitan, which is used as a pivot during ritual dances and serves as the "passage of the spirits" by which the Loa; the spirits, enter the room during ceremonies. It is around this central post that offerings, including both vèvè and animal sacrifices, are made.

Free people of color owned the most property in Louisiana but of course, that didn’t go down in history because the whites didn’t like it. As for Erik’s family, his mother and father were free people of color that became sugar planters, for slave owners, and they also shared Haitian refining techniques to successfully granulate sugar. Erik favors his father more so than his mother, sometimes confused as his father’s younger brother.

The Colfax massacre and the Coushatta massacre happened in 1873. This sparked fear for Erik’s family and they held a certain Fete for Lwa which is a public ceremony. The drums beat, the congregation started to sing and dance for the Lwa. The Lwa came to the ceremony via possession. The Lwa prophesied, healed people, cleansed people, and blessed them and assisted them in resolving issues. Erik was 17 years old and he didn’t share this with his parents but he was running for his life from a group of white Southerners one day when he was walking the bayou of New Orleans. Erik ended up sleeping in Baton Rouge until the morning.

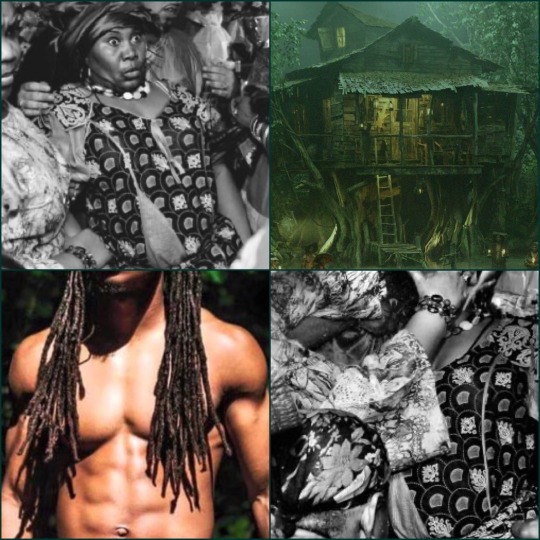

Erik often stays within the Ounfò, well into adult age. He became a hounsi bosale like his father, often participating as a ritual drummer or an ountògi. He would sing specific songs in Haitian Creole with some words of African languages incorporated in it. He was a Food Artisan like his mother. He admired her craftsmanship in the kitchen. Cheeses, breads, fruit preserves, cured meats, beverages, oils, and vinegars were some of her handmade specialties. This is one thing that attracted women to Erik besides his handsome features. He was Strong, tall, studly, rough around the edges and not afraid to challenge someone to a fight or a gun battle. Erik was charming, protective, heroic, funny, cocky which earned him the nickname “Big Ego Ricardo”. Erik was hard-working, religious, smart, sculpted, dependable, and an amazing lover in bed.

Long dreadlocks, whiskey-colored eyes, full, soft lips, and a smile with dimples so deep it charmed anyone. He wore fundamental ivory cotton band collar work shirts unbuttoned to show off his defined pectorals because he was proud of his body, sometimes paired the shirts with a vest, cotton brown or black knickers, riding boots, and a series of Vodou jewelry around his neck and on his fingers, some with symbols representing Papa Legba, La Sirene, Ogoun King, and Baron Samedi. During Vodou rituals, Erik would wear a cotton cloth around his head like a bandana, bare torso because of the amount of sweating he does during drumming to keep up with the dancers, Vodou symbols painted on his face to represent whichever Loa they were serving, white linen pants and bare feet.

He was obsessed with guns. He would often go down to the bayou to practice with stolen pocket pistols, shooting empty glass bottles and bean cans. He’s a protector, he did this just in case his family were in danger. The symbol of Vodou love on one of his ring fingers is what attracted his late wife, Justine LeBlanc to him when he was 27 years old. He was selling artisan bread one afternoon from an open shop window on Bourbon Street. Justine was six years younger than Erik. She was a Creole of color from Louisiana, like Erik, except her family were sent to Louisiana on slave ships from sub-Saharan Africa instead of Haiti like Erik’s family. She spoke a bit of English, and French with words from African languages. Erik spoke English and Haitian Creole with a little bit of Portuguese and Spanish.

Justine LeBlanc worked closely with Marie Laveau, who was rumored to be the granddaughter of a powerful priestess in Sainte-Dominigue, who began to dominate New Orleans Vodou that later became Louisiana Voodoo. These spiritual leaders served a racially diverse, mostly female, congregation. Weekly worship services took place in the homes of Voodoo leaders. Their sanctuaries were characterized by spectacular altars, laden with statues and pictures of the saints, candles, flowers, fruit, and other offerings. Voodoo ceremonies consisted of Roman Catholic prayers, chanting, drumming, and dancing. Vodou was brought of Haitian origin, however, the type practiced in Louisiana later in years is almost always known as Voodoo.

Erik was known to be a ladies man. He spent time flirting and fucking woman within his community. Pussy was practically thrown at him. Justine, however, changed all of that. They spent so much time together within one summer that Erik decided that he wanted to jump the broom with her which was symbolic of sweeping out of the old and sweeping in to the new to welcome a new household to the community. Justine lost her virginity to him the evening after their marriage and that’s when they started having children. Erik has two young twin girls; Rose Fabiola Dupoux and Felicie Ines Dupoux. After that, Justine couldn’t conceive anymore which she was often depressed about. Erik wanted to be fruitful because his mother came down very ill when he was five and she couldn’t conceive either. It was either her life or her ovaries so she had them removed.

Despite everything going on in America with slavery and racism, Erik; Ricardo, lived a happy life. He was feared and respected, a following of close male friends were like his comrades. They had his back, Erik had theirs. That all didn’t last very long. In June of 1884, when Erik was just 28 years old, things began to make a turn for the worst. Erik’s father, Jacques Dupoux, was lynched. With the 1880s dawning, a new era of violence ensued. White supremacy represented a central tenant of their platform and led to even greater levels of violence as they tried to reverse the advances made for African Americans during Reconstruction. They capitalized on rumors that black crime had expanded after the abolition of slavery. As a result, the number of lynchings soared across the South and hundreds of lives were being taken. Lynch mobs often justified their actions as attempts to defend white Southern womanhood from “libidinous” black males.

This angered Erik, causing him to gather a following of men who also lost family. Erik led the revolt to fight back white supremacy. They attached about 15 homes and killed between 55 to 60 whites throughout Louisiana. They also arrived on a local sugar and cotton plantation that often sought help from Erik’s own family for harvesting sugar cane. The revolt and about 20 slaves burned the plantation to the ground but that wasn’t before they hacked the entire family to death. Erik was made public enemy number one. His face was on wanted posters throughout the South but he was depicted wearing a scarf around his mouth and nose. Of course with Erik’s actions, some of his family and friends suffered. Vodou rituals were invaded and the members slaughtered. Marie Leveau and her following were protected but not Erik’s lineage.

Ricardo Dupoux AKA Erik Stevens returned home after successfully burning down another plantation and killing the entire family, including the children, execution style in 1886. Marie Laveau warned Justine that Erik was dangerous and he would endanger her and the children if she stayed with them. Marie instructed Justine to bring her something that belonged to Erik, something sentimental. Justine brought her Erik’s father’s ring that he wore around his neck. Marie performed a ritual that later informed Justine that Erik was in grave danger and this life as Ricardo Dupoux would soon come to a bloody, gory, gruesome ending. Marie told Justine that she couldn’t interfere because that could possibly go badly. Justine had to keep that big secret to herself to protect her children no matter how much she loved and adored Erik.

Erik wasn’t himself anymore. He became this angry, rude, vengeful man that killed without a backwards glance. He also turned to what is said to be evil magic in Vodou. Instead of becoming an Oungan, Erik became a Bokor and an occultist. A Bokor is a Vodou witch for hire who is said to serve the loa “with both hands”, practicing for both good and evil. Their black magic includes the creation of zombies and the creation of ‘ouangas’ talismans that house spirits. Bloods are usually chosen from birth but Erik was instead initiated in. He found the spirits, the orisha’s the Eruziles, not a priest in the flesh. The whites kept crossing the line in a spiritual and physical sense, it became Erik’s right to protect himself and his family with curses and hexes.

Erik caused moderate to severe suffering to those he seeked revenge on by hexing them and also using dark charms such as curses, the most heinous act on an individual; the worst kind of dark magic. He performed blood maledictions, a specific type of curse that may not kill the target but can remain within the victim's body, and be passed down as a genetic defect that can resurface generations later. Erik would inflict intense, excruciating pain on his victims, poison them, and cause flames called Move Dife which means “bad fire”, an enormous flame infused with dark magic to seek out living targets. Fabiola and Justine were afraid and they didn’t support Erik’s new choices. The light she saw in her son was indeed gone. He was of greatest fear within his community and within the Southern white community.

How did Erik meet his demise?

It happened in June of 1888, five months before Erik’s 33rd birthday. The White league and the Ku Klux Klan had been deactivated since the 1870s but some members worked closely together to hunt down and kill Ricardo Dupoux, soon to be known as Erik Stevens. He decided to use Erik Stevens as an alias since his name was so well known in Louisiana where he lived. No one besides the people close to him knew how his face looked since he wore it covered but his name however was remembered. If things didn’t go as planned for him and he needed to flee with his Mother, Wife, and children, he could have his name changed to Erik Stevens. A trusted friend named Augusto Richard’s wife named Beatrice Richard and her five children were held at gunpoint in their home. They found out where Augusto lives and used that as they way of finding Ricardo.

From what they tell him, Augusto’s family will be freed if he agrees to help the Southern white men capture and kill Ricardo Dupoux. At first, Augusto declined and said that Ricardo is a trusted friend of his. They punished him by beating his wife and threatened to hang her from a structure similar to a gallow. Augusto finally gives in, joining forces with the evil white men in exchange for his family's protection. Ricardo and Augusto have been friends since they were children. Augusto was sort of a co-planner with Ricardo to attack white supremacy and racists homes along with plantations. Augusto fabricated a new place to attack, suggesting that him and Ricardo go alone this time. Ricardo agreed without hesitation because he trusted Augusto. They arrived by horse outside of New Orleans near Maurepas Swamp……..

_______________

“Augusto...poukisa nou is it la?” Ricardo asked Augusto in Haitian Creole why they were there. He didn’t like speaking English just in case he was overheard. Ricardo’s eyes squinted suspiciously around him before he cut his eyes that looked black in the dark at Augusto.

“Mwen regrèt, frè,” Augusto spoke with a shaky voice, tears flooding his eyes. He told Ricardo that he was sorry.

Ricardo pulls out his pistol, aiming it at the shadows of the trees. He couldn’t believe he was being set up by someone that is supposed to be his friend. Ricardo told his wife and mother that he would be home safely and for them not to worry. He couldn’t trust anyone now. If he got out of this alive, he was going to cut ties with his followers.

“Well, well, well...look what we got here, a nigger with a gun!!”

Ricardo follows the source of that thick southern accent echoing in the night and finds a white man standing behind him with a gun pointed at his temple.

“Drop it, boy, or I will splatter this here swamp with ya monkey brains,” He threatened while making his gun click. Ricardo could see out of his peripheral more white men stepping out of the shadows. The moon light made the weapons in their hands shine.

“Listen to him nigger!!!” One yelled.

“AIN'T SO TOUGH NOW!!!” Another yelled while a series of laughter came soon after.

“Listen, I know ya can speak English, boy. Ya friend here told us everything. How ya niggers get a hold of books I wouldn’t understand,” He laughs before spitting in his face, “I’m gonna enjoy killing ya, just like ya enjoyed killing my friends ya fucking animal. This is how we’re gonna celebrate the ending of slavery...we’re gonna gut ya, and then we’re gonna throw ya filthy dead fucking body in the swamp so the gators can finish ya.”

The foul breath of this white man would have made Ricardo puke if it wasn’t for the gun pointed at him.

“Hey, Jenson, pass me my knife!” He yells, “I wanna Kill this one slowly.”

Like a swarm of stinky flies, the white men crowded Ricardo, some kicking him in his ribs, others in his face, bloodying him up. Ricardo didn’t drop to his knees willingly, he took each and every blow like a champion, even when his vision blurred from the blood trickling from a gash in his head from being pistol whipped. Augusto stood watching the entire thing. He was Disgusted with himself for allowing it to happen.

“Should we kill his wife? His mama? His little girls?!!!!” One of them punched him in the face while two men on each side kept him still since he’s so damn strong. It was almost inhumanly strong.

“AUGUSTO OU FUKIN TRÈT!!!” Ricardo yelled, before spitting out blood on the dirt covered ground. He called Augusto a fucking traitor, “Mwen gen yon fanmi! ti bebe mwen yo! ti bebe mwen yo! ou trèt!” Ricardo growled angrily with his deep fearful voice. He could only think about his family right now. What if some of these men were watching his house right now? They definitely were plotting something besides beating the living shit out of him in the swap.

“Kick this nigger down!!! It’s six of you and one of him!!!!”

A blow struck Ricardo’s spine so hard he felt it snap. He was on his stomach, his cheek hitting the dirt painfully. One foot was placed to the back of his head while angry tears fell from his eyes.

“Any last words? And say it in English before I slice your goddamn tongue off,” The man with the boot to his head spoke harshly.

Ricardo clenched his jaw while breathing in the dirt. He didn’t want to give them the satisfaction, however, the asshole in him wanted to toy with them.

“...Which one of ya is da father of Helen Landry?” He asks.

It was silent for a second until the boot on the back of his head was gone, being replaced with a hand yanking him by his dreads, lifting his head from the ground. Ricardo smiles smugly, his bloody smile almost as sinister as the blood from the gash in his head flooding his eyes.

“Let me ax ya something...are ya the reason my little Helen is dying? Doctor says she only has three days left...ya poison my little girl with ya voodoo magic?”

“I CURSED ya little girl with my Vodou magic…” Ricardo spits his blood in his face, “And if I were ya, I would go check on her, Doctors don’t always tell da truth.”

Augusto flinched when he witnessed Ricardo being kicked in the face. His jaw had to be broken now. He was being lifted off of the ground again, a sharp whimper of pain escaping his mouth. His feet gave out beneath him and now he was being dragged. His chest and abs were covered in dirt just like his handsome, swollen, and bloody face. His busted lip drooped and leaked blood while his groggy voice tried to form sentences. The men laughed at him but all Ricardo did was look at Augusto with unblinking eyes, one of which displayed broken vessels.

“Anything else ya got to say, nigger?”

The source of the voice didn’t matter to Ricardo. All he kept thinking about was his family and how he failed them. His father was probably ashamed. Ricardo looked towards the sky. If only he could call on Baron Samedi or Maman Brigette. He wasn’t in the safety of his Ounfò either. He could only hope that at this moment his mother, Fabiola, was summoning the spirits.

“Guess not, hold him down.”

With a dull, jagged knife, Ricardo was stabbed in his stomach. He felt like he was punched. The impact pushed him back a little and he wheezed. A tearing sensation and a noise followed. The pain took a while to kick but he could feel the blood trickling. When it was finally withdrawn, he felt something hot and cold at the same time, pulling the skin with it as it's removed. Ricardo’s cry was a brilliant sound to them, guttural chokes mixed with an agonized roar. His fists clenched and shook each time his skin was being torn to shreds. The knife rotated and the sound of his muscles and nerves being gouged growing louder. Then, without warning, the white man jerked it all the way into his stomach, until the shiny metal had disappeared inside him and the black handle was pushing against his broken skin.

“Die Coon!!!” They yelled in unison before celebrating with loud hoots.

“Look at him choking! This ugly motherfucker is bleeding out! Let’s take him to the water!”

Ricardo could feel his body falling to the ground. His hand clutched his wound but blood seeped between his fingers. He felt weak, his eyes opening and closing. Augusto stood there spewing apology after apology while crying hysterically.

“As for ya,” the white man that stabbed Ricardo multiple times drops his knife in the dirt, reaches in his back pocket with his bloody, cut up hand and pulled out a gun, “what? Did ya really think we were gonna let ya go free? Ya just another disgusting nigger too, and ya nigger bitch, ya nigger kids? Dem dead too.”

Ricardo watched with low eyes while Augusto took his last breath before being shot in the head, point blank range.

“Wastin’ all dese good bullets,” the white man pocketed his gun again, “Hall em’ up! Let’s take em’ swimming!”

_____________

Crowded tabletops with tiny flickering lamps; stones sitting in oil baths; a crucifix; murky bottles of roots and herbs steeped in alcohol; shiny new bottles of rum, scotch, gin, perfume, and almond-sugar syrup. On one side was an altar arranged in three steps and covered in gold and black contact paper. On the top step an open pack of filterless Pall Malls lay next to a cracked and dusty candle in the shape of a skull. A walking stick with its head carved to depict a huge erect penis leaned against the wall beside it. On the opposite side of the room was a small cabinet, its top littered with vials of powders and herbs. On the ceiling and walls of the room were baskets, bunches of leaves hung to dry, and smoke-darkened lithographs.

This is where Ricardo Dupoux rested upon a makeshift bed surrounded by oil burning candles. A sulfurous rotten-egg smell that is often associated with marshes and mudflats occupies the room. His entire body ached and the sharp pain prickled his scalp. Licking his dry lips with his equally dry tongue, Ricardo tried looking around with his sore eyes but the discomfort caused him to close them. It felt damp and gloomy around him, clearly nothing is quite what it seems to be. Ricardo could feel a powerful energy surrounding him, if only he could move his body. A few rickety floorboards creaked like someone was sneaking up on him and it made Ricardo jumpy. He wasn’t physically able to help himself.

“Ricardo Dupoux, ki sa yon sipriz bèl eh?”

A seductive voice of a woman spoke to him in Haitian Creole. This wasn’t a pleasant surprise exactly.

“Kiyes ou ye?” His voice was so hoarse and his throat felt raw.

“Who muh? Well...I’m yuh rescuer of course, handsome.”

“Kisa...ki kote sa a?” Ricardo coughs painfully. He could taste blood in the back of his throat.

“Well, don’t Yuh sound sexy speaking deh Creole to Mama Dalma. Yuh in muh shack, Ricardo.”

“Mama Dalma? Prètès Vodou a?” He spoke with astonishment.

“So, muh assumin’ yuh heard stories about muh from way back when...what else do yuh know bout’ me?”

“...Nothing.” He finally speaks English.

“Yuh know so much about muh voodoo mystic powers in the Caribbean 175 years ago…I’m honored.”

Finally, standing above his shell of a body was Tia Dalma herself. Tia Dalma was a practitioner of voodoo, a hoodoo priestess with fathomless powers that was perceived as a legend. Supposedly, she has uncanny powers to foretell the future, to summon up demons, and to look deep into men’s souls. She’s mysterious and beautiful with delicate patterns accentuating her hypnotic eyes, long but slender dreadlocks like him, deep melanin skin so smooth and unblemished, and lips painted black. She wore a sheer black dress that showed off her nudity beneath it, so many curves that looked delicious, and a mystical necklace dangling between her small breasts. Ricardo could feel her seductive energy enticing him into a tangled net. She playfully giggles while stroking Ricardo’s bare, sweaty chest with her long black nail flirtatiously.

“Poor baby, him carve yuh up?” She spoke with her Jamaican Patois. Mama Dalma looks Ricardo up and down like she wanted to mount him. She was so happy she couldn’t hide her beautiful smile.

“Did ya heal me, Mama Dalma? I thought I was gon’ die by a white man’s hand.”

“I’ve seen yuh fight big brawla, I’ve seen yuh cap a shot, I’m impressed wit’ yuh...haven’t seen a man deh brave in a while...queng dem white boys.”

“...ya been watching me?” He squints his whiskey colored eyes,“who ya for ya to be watching me?”

“Mhm, I been watching yuh, handsome...It’s because I want to save yuh...give yuh a better life than this.”

Ricardo was shivering, his skin pale and cool, difficulty breathing, mentally confused, and his blood pressure kept dropping. His chest was rapidly moving from breathing too fast, heart rate beating so fast it was almost painful, and he felt like he was running a fever.

“Easy nuh, yuh going into septic shock.” She takes her hand to pet his dreaded hair like a baby with the back of her hand.

“W-what?” His lips trembled. He was numb.

“Awoah. Muh herbes are keeping yuh stable but if I take deh herbes away...yuh die.”

Ricardo closes his eyes.

“Unless...yuh have two options, handsome.”

“One’s that I should trust? How do I know ya not poisoning me? Hm?”

“I’m gonna ignore deh...here are yuh options. Yuh can stay here on muh table and die slowly...or I can give yuh immortality.”

“Imòtalite? Baron Samedi?” He almost choked on his own spit from trying to speak.

“Better than the power of a Loa...yuh be immortal until meeting deh true death. Yuh have superhuman physical abilities, senses, flight, and healing.”