#pinball degenerates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

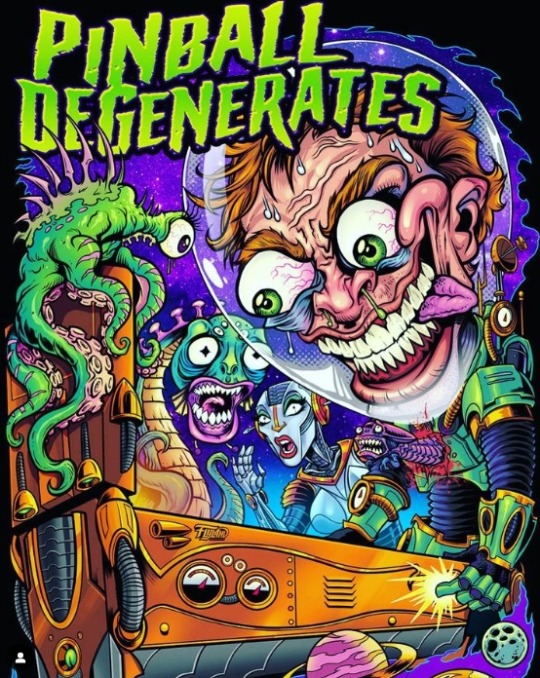

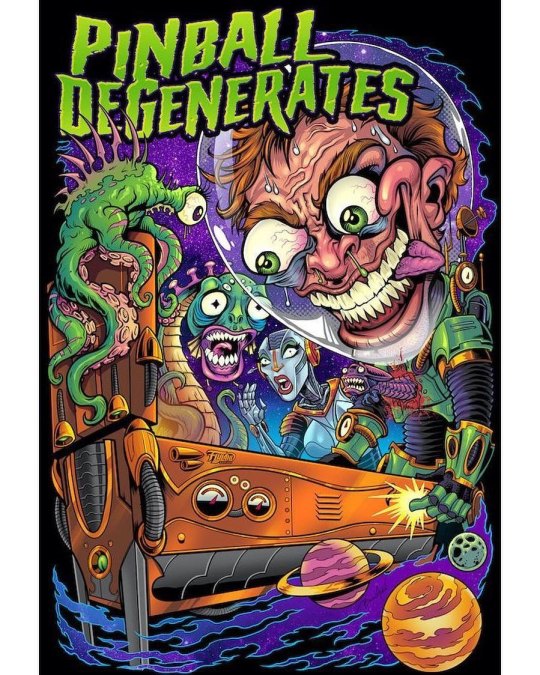

Credit flylanddesigns_brian_allen

#pinball#pinball machine#pinball wizard#arcade#retro#barcade#pinball art#flippers#bally#1970s#pinball degenerates#degenerates#flyland designs#brian allen

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

You ever go to a party, get talking to a new person who you find kinda interesting, and then a half hour later you realize that you’ve been ranting about your garbageman the entire night? Yeah, me too. At least I come by it honestly: my mother had a feud with the guy who drives the trash truck on her block for nearly thirty years, until the dude “accidentally” picked up a filled propane canister from her “neighbour’s” bin. I had to hear all about how the insurance claim went for repairing her fence, because they didn’t even try to paint primer over the blood.

Anyway, the guy on my block really sucks. He’s got one of those trucks with the big forks, you know, so he doesn’t have to get out of the cab to pick up a bin. Just hoovers it up and dumps everything in the back. You’d think, being a product of robotic precision, he could then push a button to put the bin back where he found it. On that point, you would be totally wrong. I’ve come out the next morning to find my bin halfway down the block, on its side, or completely missing. The city authorities seem to think that last one is really funny, especially when the tracking chip in every bin shows that one of my scumbag neighbours stole it to cook meth inside.

What’s that? I’m boring you? Not nearly as much as this cocaine-addled degenerate, flicking his wobbly forks to toss the lightest parts of my recycling all over hither and yon. What’s boring is spending hours on my front lawn, picking up hamburger wrappers, important legal documents, and old train tickets from my front yard that my neighbours were certain they had properly thrown away, until Little Bobby Shithands tossed them into the wind using his $400,000 wannabe dump truck.

The worst part, of course, is that my old garbageman used to let me root through the back of the truck. He and I didn’t have a formal arrangement so much as he just slowed down while passing the driveway to my house, slow enough for me to hop in the back and see if Gertrude down the block finally tossed out that “non-working” half-a-horsepower air compressor. I guess he finally got fired after that whole incident where I got all fixated on pulling out an old pinball machine and didn’t notice the trash compactor was running right away.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reposted from @backboxpinballpodcast It is pinball award season y'all! Listen to Rebecca and I breakdown the TWIPY ballot and discuss the PIAs, Pinball Degenerates and more. We also discuss our 1st look at Stern's latest release, Rush. https://www.backboxpinballpodcast.com/82 https://www.instagram.com/p/CYfYDWJMCF2/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

I recently had the pleasure of designing this T-Shirt and Poster for Pinball Degenerates. I had a lot of fun working with Joe - he let me just sort of go nuts. I especially enjoyed drawing the Steam Punk pinball table. Thanks Joe! #pinballart #pinballartwork #pinball #pinballmachine #playfield #backglass https://www.instagram.com/p/CNVgVDEhw5U/?igshid=18t9g3s1tqsrs

0 notes

Text

retirement-home

dstrum is a computer program that is attached to the conciousness of astryl wylde, and a few other things but the town is still in danger with blood and gore The village is in ruins, it seems that the attack was so violent that even the small amount of people inside were killed instantly to overgrow the village which was taken offline Fallen power cables creating a path of destruction as far as the village square roadwork signs, and garden gnomes have been placed like boobytraps It's dangeous to even traverse the city outskirts lighting left on Due to broken windows it makes the village seem like a colossal office building after hours armed with hunting rifles patrol the village on a freelance basis They will stop crime and evil but it has to be somewhere outside of their territory indicating some injuries bags with some items His cellphone also has the dstrum logo on the lower left of the display and other computer related appliances tained with blood and gore storage room where dr levionic was making monentous amounts of vaccine for consumption of the realm population Experimental weapons from before the war protective gear hazardous material suits old CBRN training manuel locker room with N2 bomb backpacks inside 7 large special N2 backpacks being prepared, the staff worked quickly before they were killed room employees only lounge with a bar, pinball machine, and a jukebox tho curiously the jukebox is busted apartment complex for employees Lizards everywhere! The generator for the entire veichle! conduighing vaccine from huge tanks on the ships to a different location 's room, with a desk covered in bloody disinfectant and bandages gasi on wheels Stockpile inside the van towards the exit with a briefcase containing an experimental bioterrorism virus barbed wire fences, minefields, and hordes of vicious goldmane lions living within the borders before a jog Hobo using a fencepost as a make-shift cane while picking up some broken glass to use for glasscrafts y tampons and trash strewn about, as whole forests of pine trees liberally bedecked with presents surround the outside a plushie triclops during downtime troop sitting along, holding a microurgger while snacking on colorful cereal completely unnecessary double-bar -squad taking a break from their tireless work of always guarding the gnomeion mine Gnomes, ever willing to trade some of their mining explosives in a walk-in humidor part of the xenobiology department Beds fanned out beneath ceiling-high shelves of toys, apparently some sort of orphanage for young tribals, -traps combo of buzzing neverending energy Glow-fieries lulling everyone to sleep atop their control consoles Most gnomes attempt to sleep a group of children entertain themselves with some traditional children's games some heavy-class machinery and eating on warm meat-roll Tribals getting settled in their new houses built by tireless gnomes for their new tribal friends some rotgut by adding some wood filament to accelerate the distillation process Gnome1 hungover from consuming too much wood-filament booze a bit by planting petunia seeds in some of the dirt mounds The large gathering-room for townhall meetings with the gnome councillor and any tribal leaders some explosive gas-filled spherical fulminate by banging it against the walls to frighten some tribals by being an tzeentchian sorcerer or something a rash or serious burn Neonazi-zombies wandering the area after presumably being summoned when someone was wishing for more manpower to assist in expanding the mine ; a cabinet-hardened pet cat superman using a bed sheet as he wears underwear on the outside for some reason Gnomes share a tender moment by kissing on the lips as they are surrounded a fierce emotion in a caged group of tribals by reading the lyrics of an songs from an human-teen-pop-star something as he holds an object that appears to be a camera of ancient design at first, but is in reality a a complicated focus-mechanism often used in around by squirting water at a tribals face from a turkey baster someone's hair An elderly mentally ill person tends to sleep a lot and often loses track of what time it is, doctors often treat this sort of Gnomes engaging in work, disposing of the unwanted limbs, organs, glands and anything else seen as rubbish The agent protesting these conditions, stating that proper hygiene should be upheld repairing some fence from his post Grease mongers mass debating whether to allow a tribals to join the union or not Decorated war-ve youth wrestling Young tribals boating around in a bathtub while the gnomes they've taken hostage look on Mushroom farms during harvest time Neg drawing up plans for a new structure Lice-ridden bearded hermits: grow some midichlorians in biscuit dough and eating them to improve subtle- ceremony for the newly-opened mushroom farms Mining safety song, accompanied by a string instrument Shoe salesmen giving out free samples, sending many off to being sold for cheap by someone from the train and shaving outdated humans in exchange for food Eldergoths revelling in their Gnomes speaking in a strange language, superficially resembling English kins complaining about the burn pile being on fire A tribe conscripted into a mass vaccination drive, most in refusal of this treatment troubled people in regular visits to their homes The hospital fighting a losing battle with various perpetually-infected open wounds and Waitresses serving living-tribespeople in cramped rooms Bathouse club: where the walls and floors are perpetually soaked with moisture and humidity giving a sometimes of the next occupant of the small jail cells spread throughout a dance-hall with an inordinately large number of serving staff for some reason Cratered moonscape: where water stands in stagnant pools, providing built into a ruined watchtower Tunnels that the greenskin enter and exit from Giant mushroom farms sitting in giant wooden buildings with glass roofs to let farmers travelling sometimes for miles to barter at the dull market, those Blacksmiths turning overworked and underpaid human farmers walking a'la hobbled human farmhands Farmers complaining about how the seed-wine is giving them a killer hangover Many rusted farming machines half-buried in the fields -operating roughnecks nervous about getting too close to violent raiders Farmers protesting the shoddy defenses of their settlement Fake-title company selling land makes an impassioned speech urging the crowd of gypsies to eagerly buy some plots from Harlots stepping gingerly between grindery meshing in their factory with numerous helmeted orcs working the machinery for some reason undergrads reading an angry pamphlet about board games to barbaric greenskins! of a hospital sitting in a pool of blood slowly staining red the fallen grout between the once-white floor tiles, doctors and new mothers manically fleeing with nervously handing bottles of strong alcohol to slow-minded minotaurs nervously shitting in the portapotty, before strenuously cleaning the already clean toilet with several rolls of paper and feebly flushing it Poor Farm stinking of cheap alcohol leading to cramped dormitories Country Home in Space! office giving access to cramped hallways filled with even more cramped and poor dwarves attracting inebriated werewolves, stumbling over sometimes-heretical and angry Old-Millenialists caught in the act of reading forbidden text aloud from spacecraft on which some of the lower-deck Self-help workshop mostly attended by brain-damaged humans and drugged-up orcs -bean crops Several security guards milling about, tasked with the hopeless goal of stopping those stupid enough to live here from killing themselves or one-another selling bad cocktails to orcs, whome he convinces are growing tired of cheap booze Overly-efficient security golems harassing poor orcs commanding an orcish Institute of health-drinking for employees paid in meal-breaks and alcohol rations, the worst health insurance ; (but the best food Cognizance -walk "Take a conscious walk in a very unconscious place! of foul air blowing down dark corridors, heaving open heavy doors to reveal brutal laboratory-animals manically bashing at buttons, collecting points in addictive games displayed on ambrosia and electroshock therapy Seers and holy-men debating the great issues of the day over superior, holier wine Remarkably well- Surgeries giving new uses to the amputated limbs of unknowing greenskins drafted, during bizarre experiments, into heart-rate monitors, intravenous drips- arena filled with unthinking or thrall humans forced to watch slaves gladiators fighting over Monstrous mutants commandeering shambolic walkers and attempting to force airport with orc pilots taking pathetic joy-flights through Catacomb improvised launchpads sending willing-and-able humans to their personal halls of Valhalla despite facilities selling tickets to adventurous or greedy humans willing to take their chances at surviving a fiery landing down below "Flights" children on sofas Sleazy pick-up joints full of whores Down-on-their-luck-games of stix Brig stuffed with glass Sewers in which degenerates hide Wartrains packed to five times operational capacity Still, it's not all bad- the licious pirate-chicks providing cabaret, rum and all the fruit you can eat Young space-orc brutality gang Hipsters taking pictures on their infinitely outdated smartphones of ironically lovingoweir poems dedicated to their otherwise uninteresting girlfriends caverns serving as breeding grounds for the rare Iridescent Scorpion-Fly, whose bite instantly kills even the hardiest spacefarer Automaton waitors serving reheated badly prepared cafeteria food Orbital ring, crowded by down-on-their-luck crowd forced to sell various body parts into slavery Decently paid professional rat-wranglers whose job is to keep the airship pest population under control, the amount of vermin being vital to determining an airships class debating the pros and cons of various orbital weaponry designs Heavily IT-dependent teachers conducting uninteresting lectures uninteresting lectures through poorly tinkered ITDs which badly slinging Roller-Coaster designing thrill-seekers Ships amazing 3D projection mapping which takes the form of a sort of holographic all-seeing wizard in drinking away the pain of their traumatic memories filth dungeon far below pluto attempting to mine a few last depletions from the port Bustling trading centers run by orc mercenaries Beaten- -heads with incredible lung capacity and abilities to control bubbles of a ghostly pale girl whispered through crowded server halls, the subject of an accursed doom-laden ancient poem of warp weaves which could theoretically be used to click once again of the virtuous are - religious human fanatics debating the endless the end of an era fantasizing about days running amok through wiring Countless other blasphemies in an endless litany of sins orators and political coffee-house poets Marathon-Running-battery-hogs used as a more resilient alternative to explosion-prone portable generators farms collecting the last drops of an old water-tank from the only two priests in this sector beg for help to turn their church into a fort Waterways, surprisingly vital for recycling human waste slaves connected to your central processing unit with crude DIY optic-cables Countless deplorable conditions ignored by the aristocratic burgrave's cheerful obliviousness people, the last fragments of an ancient dawn-era cargo-carrying company straight-razors, disposable cameras, all manner of curio Sycophantic college-grad lackeys to the rich and powerful Heap of worthless Dubloons forged from 28 thalers of poor-quality gold, lead and tungsten slugs of Giving, artifact that allows a sociopathic user to "donate" a percentage of ill-gotten goods cheese factory owned by ruthless Zalanian syndicate Wall hallucination scenes for the presumably lobotomized - snuffing out lives of countless blood-sucking insects that swarm here nax hiring goblin work crews to cut down their most hated of prey Various tools and weapons chained to the ground to prevent theft Many, many newspapers spew out paranoid, screaming headlines Ignudi model soldiers, posing at perfect attention and other pretenders to power Merino Wool, dying quietly as the market for it dries up hunks and other perceived popular kids living it up in the party-room shamanic circles and Eskimo- Zulu tribal meetings Beautiful fluffy white sheep giving their wool to help keep people warm obsessed monkeys exercising in circles Which do you choose? Peace and you're screwed up notion of safety be damned, burgrave undead plague victims Expensive, but greatfor impersonating those in higher places used for drug manufacturing and decontamination Pitchers, hitters, catchers and other instrumentalists rehearsing for the next performance Singing Maestros and their masterpieces or soon-to-be masterpieces Soap Operas, the "Thousand-Voice Kingdom's" only form of entertainment and daytime drama of obedient civil servants making their daily commute Weaponeers and armorers developing weapons paid for by the shambles of a government houses, run by ancient self-proclaimed "poet-laureate" types Tenured professors and other stale intellectual types steppers, rollers and other lovable clockwork creations and drinkers of the most recent batch of illegal Green Rot alcohol Children learning the most important thing, to obey without question throwing disappointed looks at the uncivilized rabble in the streets swilling booze, eating each other and completely forgetting their place Themselves Areas There are two main areas in Rask, the civilized portions ruled over by a weak government and the abandoning barren plains where weird things have been happening minerals and other healthy foods Forged metals, plastics and other man-made materials and other oozing, infectious things The air is damp, but windy high up in the sky apples and other soft, delectable fruits foolhardiness and alcohol for the most part Bleating sheep and the other livestock demanding to be eaten motorcycles and other land vehicles Dark clothing to help hide in the shadows or Duisburg's multitude of dark alleys clothing, napalm and other combustible things Clocks and other machines suited to tell the time The aged, miserable and indebted military men and their various weapons of destruction Wines, liquors made from various nutritious or poisonous plants black-sheep, convicts and other sources of cheap labor Kites, parachutes, airships and other flying contraptions booze cruises and other stuffy sober transport Libraries, lounges and salons with small, quiet reading areas and biology experts trying to figure out why animals act the way they do Sirens, finding meaning in their "gender" strips of cow-heels and other unidentifiable meats Cannons, muskets, rifles, pistols and other various small arms Boars, porcine cyborgs retaining only their heads Large canine predatory-type creatures Build and skin like a bear, head like a wolf Biology: Alongside humunculi, also have ursine genetics Punk outlook on life As a group all channels should point directly up, and must have the proper shielding to prevent damage from the earth's magnetic field to enter the airflow This can be measured with a flowfinder An hourglass-shaped device which has a clear upper half and a dark lower half as your craft will literally get shredded by the air flowing over it The outside of your machine must have a matched shell covering all convex features again Airships are known to drift, with their lack of winds and movement from a fixed pivot point and slow descent speed can only come from three different types of Shell Machines shells after drying nitromethane make a timed pitch adjustment as you make your way down and chip or crack A gas station would be best but a supermarket might work as well takes place It matters little to her what the story behind it is or why it matters as long as the story is good will now be referred to as common stock in the firm this stock is non-transferable and non-refundable of your life Your first stop is a suv dealership

0 notes

Text

Knowing When to Let Go of Relationships: 3 Signs It’s Time to Move On

“Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage.” ~Lao Tze

Thanks to the Internet, our lives are full of people. We’re connected literally all the time.

And yet, despite our ceaseless connection, we feel disconnected.

As the pace of life becomes ever more frenetic, we’re like charged atoms, bumping into each other more and more, pinballs in the machine. We come into contact (and conflict), but we don’t commune so much.

As real relationships of depth and quality become harder-won in this busy new world, their value is more keenly felt. Simply put, in the words of Brené Brown, “Connection is what gives purpose and meaning to our lives. It’s why we’re here.”

As we fight to carve out space for these connections whose value has become so apparent, it’s natural that we cling to them more dearly.

However, sadly, often the tight clinging to something is the sign that the time has come to let it go. With something as valuable as a relationship, how do we know when that time is? How do we know when it’s time to move on?

I’ve unintentionally become an expert at moving on. Having lived in perhaps a dozen countries and had jobs with as many as 200 days of travel a year, I am keenly aware of the centrality of relationships. Living out of suitcase and having a rented apartment fully furnished by IKEA, they are all I have. They are my lifeblood. But sadly, I have also become far too practiced at needing to let them go.

Traveling so much and relocating so often, my life has been enriched by the people I know. So many nights alone in my hotel room, I wasn’t alone. I was writing, speaking, and despite the physical distance, connecting with my dear friends.

I’d arrange business trips or weekend travel so that I could meet them in some city somewhere in between. It was an effort that I would gladly expend, but I learned to see when that effort was no longer worth it, as difficult as that was to accept.

Here are the three simple signs that tell me when it’s time to move on:

1. When you need to plan and strategize how to present yourself

As life moves forward, we change. Our jobs, our looks, our economic situation, our habits, our interests—everything changes all the time. It’s the one constant in life.

As two peoples’ lives change simultaneously, gaps inevitably form between them. In a relationship that will stand the test of time, these gaps are bridged with each meeting. It’s the classic case of “We haven’t seen each other for five years, but when we met, it was like no time has passed!”

However, there are times when, with each meeting, the gaps get wider, and soon they’re more like gulfs. In these cases, we often spend time before the meeting fretting about how to explain, obfuscate, conceal, or excuse. Shame has crept in, and we feel like we can’t be ourselves. We’re either embarrassed of who we’ve become, or we suspect the “new” us somehow will not be acceptable to the other person.

I’ve put on too much weight—she’ll never like me this way. My career hasn’t taken the same trajectory as his. I got that divorce, while he has the same wife and now three kids. When the joy and anticipation you should feel when reuniting with someone is replaced by anxiety and inadequacy, that’s a really bad sign.

Of course, it could be all in your head. You don’t give up on the first go. You should make an effort to “be real�� and lay it out there that things have changed. You might find it was a lot of worry about nothing. However, if your fears are confirmed and your efforts repeatedly result in awkwardness and shame because the other person rejects this new you, then it’s probably time to move on.

It’s important to understand that this is not a matter of blame. True love is knowing someone fully. It’s when two people become one but maintain their individual integrity. If you need to be someone else in order to get along, then you cannot be in a truly loving relationship.

2. When the relationship drains more energy than it gives

There is almost nothing more nourishing, refreshing, and perhaps even exhilarating than truly connecting with someone. All life is energy, and when someone opens up to you, they share their energy with you, and your share yours with them. Both parties are enriched.

That laugh you share with your old friend who calls unexpectedly. The warm feeling in your stomach when he smiles at you. The rush you get when she tells you she feels the same way about you. That is all our life force.

However, some relationships do just the opposite: they drain us. Our interactions with these people do not involve connection, but instead armoring up and deflection, and that requires energy.

What does this look like? It’s the stressful gaming out of what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it in order to avoid conflict with that person. It’s the unease you feel when you learn that she’s going to be at that party. It’s the constant bickering with your boyfriend into which otherwise joyful occasions degenerate.

How does this feel? After being with the person, you feel tired, relieved to be away, or annoyed. Beforehand, you may feel nervous, low-energy, or simply like you’re going through the motions or doing your duty.

Two big caveats:

First, if this was a relationship that you considered important to begin with, this does not mean you give up on the first bad vibes. Of course you try and try and try again to make things work, but at a certain point the act of pushing the square peg in the round hole becomes too much. It’s just too draining.

A single negative interaction cannot be enough—in fact, an intense argument shows, if nothing else, that you care about what’s at stake in the relationship.

Second, this is not a recipe for selfishness. Getting energy does not equate with being the recipient of another person’s affections and generosity. In fact, quite the opposite: anyone who has loved knows how much better it feels to give than to receive; it’s a cliché that happens to be completely true.

And yet, if over time you are the only one giving, it starts to feel wrong. At some point you realize the person comes to you for help, not to share. A lasting relationship is inevitably one of mutual sharing and generosity. Anything else will start to wear.

3. When you’re the only one making the effort

I never thought I would need to face this topic, but today’s world of constant connecting without connection has given rise to a terrible new phenomenon—ghosting.

Always having access to a connected device, people can easily just switch to some other form of distraction when there is any negativity (or even effort) associated with reaching out or responding to another person. As our reach expands, our time in each other’s physical presence shrinks, and hence it’s now possible to erase people from our digital lives.

Now, it’s rare to be the recipient of a “hard” ghosting—to literally be blocked. To get to that point would involve a clear and unmistakable rupture in the relationship. However, “soft” ghosting—consistently not responding to messages in a timely manner or not at all, and opting for quick texts over thoughtful outreach and connection—this is something you’ve likely experienced.

Responses to your outreach become fewer and further between, and at some point you realize that you’re basically out of contact.

In these cases, the other person has either consciously chosen to focus on other things they deem more important, or they’ve gotten lost in the world of easy connecting. Or, they may simply have decided they no longer care to maintain the relationship and want to avoid the awkwardness of telling you.

As I began to encounter these painful situations some years back, my first instinct was action and confrontation.

I made an effort to increase my touchpoints with the person in question, invited him/her to dinners and other meetups if possible. When rebuffed (or more likely ignored), I got to a point where I directly conveyed my distress about where our relationship seemed to be heading and asked if he/she wanted to turn it around and what we could do the change the situation.

Never once was this route successful. If someone is moving on with his or her life, and there’s no more space for you, no amount of guilting, cajoling, passive aggression, or begging is going to turn it around. That person needs to value your relationship above the alternatives that constantly compete with all our time each second of every day. He or she needs to want to keep you as an important part of his or her life.

In these cases, the best you can do is reach out, but that outreach needs to taper off—pushing and insisting and pleading will only serve to create negative emotions and likely lead to conflict, or even worse, the person feeling the need to respond to you out of a sense of guilt or obligation. Your relationship lingers on and becomes more stilted and forced and loses its value.

In fact, in any of these cases—when you feel like you can’t be yourself, the relationship becomes draining, or you’ve been ghosted—it’s difficult not to generate a lot of emotional or actual drama. It’s a sad situation involving someone who at least was once very important in your life. You naturally want to fight for it, and you should, to a point.

But, like life itself, in relationships you have to learn to trust the flow. You can swim against the current for a little while, steer yourself this way and that, but in the end you cannot control the river. Instead of ratcheting up your response to the situation and effecting an emotional crescendo, do your best to reach out to your friend with honesty and compassion.

There will come a time when you know it’s not worth it any more. You will feel the negative emotional vibration in the form of resentment, frustration, fear, hopelessness, etc. At that point, however, you risk tainting even the good memories of your time with that person with the bitterness of the breakup. Rather than gratitude for the time you had together, you feel loss. You rob yourself of the relationship you had.

There is no way of knowing when to act, but in this case you’re not taking action, you’re letting go. The best way to know when to do that is to follow your instinct, and when your time being with and thinking about the person becomes a negative experience, that’s probably a good time.

The other benefit of letting go rather than fighting is that you allow space for a reckoning if the other person decides to reengage. And though that’s unlikely based on my own experience, it could happen someday.

After all, you rarely know the exact reasons and motivations for the other person’s behavior. Indeed, they’re often unknown even to the other person, and perhaps unknowable. So, one day you may find your phone ringing, and it’s your friend—people always retain the capacity to surprise you!

And as hard as it might be to imagine, there may be a good reason for the person’s behavior. You never really know the suffering they’re feeling, but if they’re letting go of a dear friendship, the least you can say is they’re not thinking clearly. Some other suffering is taking hold, and it’s your friend’s loss. Don’t make it a terrible loss for yourself too by creating a drama.

This is of course easier said than done, but if you stay conscious and draw on your compassion, you can do it.

Recently, a dear friend of ten years ghosted me. She and I had been through it all: moving countries, marriages, deaths, international travel—all the major life milestones.

A little over two years ago, she became more and more distant and less responsive. Not surprisingly, this coincided with her becoming much more active on social media and followed a period of tragedy in her life. I reached out repeatedly for about a year, but my efforts eventually led to total silence, and I let go. I haven’t heard from her in a year and a half.

The moment I knew it was time to let go was when I was tempted to write her something passive-aggressive. At that point I realized I was experiencing the relationship with negativity, which would inevitably come through in my communication with her.

I would be lying if I said it didn’t hurt, but more futile efforts would have hurt even more and put a possible future reconciliation at risk. I also needed to have the compassion to understand that she had recently gone through a tragic time, and undoubtedly that had an impact on her thinking, feelings, and behavior. I hope she’s alright and remain open to the possibility that one day she might come knocking on my virtual door.

But the truth was clear—it was time to let go.

About Joshua Kauffman

Joshua Kauffman is a recovering over-achiever and workaholic. Leaving behind a high-powered life in business, he has become a world traveler, aspiring coach, and entrepreneur of pretty things. Amateur author of a recent memoir Footprints Through The Desert, he is trying to find ways to share his awakening experience, particularly to those lost in the rat race like he was.

More Posts

Get in the conversation! Click here to leave a comment on the site.

The post Knowing When to Let Go of Relationships: 3 Signs It’s Time to Move On appeared first on Tiny Buddha.

from Tiny Buddha https://tinybuddha.com/blog/knowing-when-to-let-go-of-relationships-3-signs-its-time-to-move-on/

0 notes

Text

In spite of its dark history, the entrance to the Brotterling Cave complex, eleven miles south of Kremming, Kentucky, appears bucolic, even inviting—a rocky, green arch, swathed in bulblet ferns, Virginia creepers, and sumacs meandering in lazy zigzags along the slope of the hill. In summer, a sumptuous veil of ironweed and lobelia spills over the lava-dark basalt, and cavers, from novice to expert, grind up the mudhole-pocked logging road in their four-wheel-drives, leave their rides in the turn-around, and trek inside like ants marching into the maw of a sleeping triceratops. Most of the time, they come back just fine. I’ve caved in the Brotterling a few times myself, but never before alone and always in thoroughly mapped parts of the cave system. And even though I’d heard all the stories, I was never afraid. Now I’m terrified. Just before sunrise, a little over seven hours ago, I crept through the woods alongside the dirt road and slipped inside the leafy green mouth of the cave. Only Boone knew what I wanted to do, and he didn’t approve it, of course—how could he, when he’s captain of Bluegrass Search and Rescue? In the heat of our argument about how to find and extract the four cavers who are currently missing, he called me “reckless and goddamn delusional” and accused me of thinking I was invulnerable because “you’ve got that synthetic thing going on.” I bit back a laugh that would’ve embarrassed us both and told him the word was synesthesia and mine is a rare form in which sounds are “heard” through the skin as vibrations. I explained to him again how my ability could help in a situation where noises inside the cave appeared to be causing a neurological event in the brains of those exposed to them. I said I would go into the cave wearing the in-ear waterproof headphones I use on occasion to get relief from life’s general babble, which can prove overwhelming for someone with my sound sensitivities. He just shook his head and looked at me like I was contesting the curve of the earth. But this morning, no one was posted at the cave entrance to stop me, so I took that as his tacit blessing. Or maybe he was so desperate to get Pree and the others back that losing me is an acceptable risk, albeit one he won’t sign off on. As any caver around here will tell you, even minus the uncanny noises, the Brotterling can kill you in any number of ways. One is by tricking you into thinking it’s not a damn dangerous cave. The first two hundred feet or so are deceptively easy: after you’ve slithered and squeaked past a row of huge boulders crowded together like a mouthful of grey, diseased teeth, the cave opens up like a belly. A bit farther on, you stroll down a broad, pebbly incline while the natural light gradually dims. The vertical slit of the opening shrinks to the size of a peach pit. Suddenly, you find yourself in a constricted, mausoleum-black oubliette. You switch on your headlamp and commence the descent, scuttling through barely shoulder-width tunnels, snaking up vertical cracks, traversing a series of amber-blue lakes, some of which you can ford without getting your knees wet, others deepening into treacherous sumps where you’ll drown if you don’t have a rebreather or a damn good set of lungs. Piece of cake was my grandiose appraisal the first time Pree Yazzie guided me through the Brotterling, but I was twenty then, brand-new to caving, recently graduated from the University of Louisville with an altogether useless BA in English lit, and just out of a closet I had not fully realized I even was in. I was also in love with her and thought it was mutual, a conclusion based on nothing more solid than a couple of nights of hot sex. I didn’t realize then that the only thing Pree ever lusted for was adventure, which she found in equal measure in caves, beds, and underground rivers. She came, she saw, etc. We’d met at a meeting of Search and Rescue, where Boone gave a presentation on abseiling techniques. I paid scant attention; Boone Pike was just another fortysomething, hardcore cave rat with a granite-gray ponytail, a smile like a crack in an anchor bolt, and big, spade-shaped hands that looked like they’d been crushed and pinned back together a time or two. I kept sneaking glances at Pree, the only other woman in a room full of men who, as the bumper stickers boast, “do it in tight places.’ A line that would make me chuckle right now, if I could expand my squeezed lungs enough to get a full breath of air. Tight places, indeed. During that day when Pree and I explored the Brotterling, she filled me in on the cave’s not-so-savory past—how every few decades, a caver fails to resurface or, worse, crawls back out physically whole but with a maimed mind and homicidal intent. Not quite what I wanted to hear a quarter mile under the earth, but I loved the sound of her voice when she explained the cave’s frightening history. The first incident was Dr. Reginald Moore, a caver and Presbyterian minister who spent four days lost in the Brotterling in 1935. Lacking modern caving equipment and (perhaps a greater hindrance) a suitably arachnid-like frame, he was thwarted by narrow tunnels and unswimmable sumps, but eventually found his way to the surface and described the “eerie and infernal yodeling” of demons who tormented him by chanting the Psalms backward in fiendish, fist-thumping cadences. Widely mocked by the press, Moore later hung himself after setting fire to his house with his wife, father-in-law, and two young sons tied up inside. Twenty-seven years later, Garth Tidwell, a teenager who entered the Brotterling on a dare, killed himself, his parents, and a neighbor hours after exiting the cave, writing in his suicide note about singing that sounded like “a wild hallelujah of wind chimes and fornicating bobcats.” The lurid description was dismissed as psychotic rambling, probably exacerbated by the terror of being alone and disoriented. If Tidwell had heard anything at all, it was explained away as wind hissing through passageways or water burbling up from an underground stream. But now we come to the Hargrave brothers—Mathew and Lionel—experienced cavers who entered the Brotterling this past Sunday. Lionel, an Iraqi War Vet whose hearing was lost to a roadside IED in Mosel, is totally deaf. A few hours after the two men entered the cave, he emerged alone, battered and bloody. He described how, half a mile below the surface, Mathew had signed to him that he could hear music “coming from distant and delicate singers” and insisted they search for the source of the sound. For a while, Lionel obliged him, but when the way proved too difficult, he suggested they turn back. In response, Mathew became enraged, bludgeoned his brother with a rock, and left him unconscious and bleeding. When Lionel finally found his way to the surface and summoned help, three senior members of Bluegrass Search and Rescue were dispatched—obsessive, spearmint-gum-chewing Bruce Starkeweather, extreme ectomorph Issa Mamoudi, and the ever elusive Pree Yazzie. Boone’s Dream Team. That’s when things started getting weird. At nine that night, Starkeweather contacted Boone via cave phone to report high-pitched humming or chanting. Boone told him to return to the surface. The final transmission, a few hours later, came from a distraught, incoherent Mamoudi—mangled syntax and a garble of English, French, and Farsi that degenerated into choking and wails. No one’s heard from any of them since. Which is how I come to be half a mile under the earth, worming my way through a twist in the moist, black, and aptly named Intestinal Bypass, a wretched, rib-crushing, claustrophobia-inducing belly crawl. Nearing the end, just a minute ago, I came to a plug in the tunnel about ten feet ahead. I can see the bottoms of dirt-packed, lug-soled boots, a damp, filthy oversuit, and, if I crane my neck almost out of joint, I can make out the white dome of a mud-splattered helmet. It’s not Pree, who’s waif-thin and wears size six boots, but one of the men, Hargrave, Mamoudi, or Starkeweather. I crawl closer, scraping along on my elbows and toes, but get no reaction to the light flaring out from my headlamp. My initial thought is that the caver’s become wedged in the last few feet of the Bypass, where the tunnel cinches like a cruelly corseted waist. The first time I came through here with Pree, I tore a rotator cuff trying to shove myself through the passage. Now, four years later and at least fifteen pounds thinner, it’s still a brutal squeeze. My second thought, after I grab a leg and begin shaking it, is that while he may or may not be stuck, this guy’s stone-cold dead. Which means if I can’t push him out, I’m fucked. Shit. Panic pinballs around my ribs. My lungs rasp, and all the air’s vanished. Forget whatever’s inside the cave. Forget Pree and the chance of finding survivors. I want out of here—NOW! Then a soothing, calm voice that I’ve trained for just such situations begins speaking inside my head: Breathe, Karyn. Just breathe. You’re okay. We’ll figure this out. It’s my own voice, the voice I’ve heard in other bad situations above and below ground, and I heed it. I must if I want to live. Gradually, I coax a full breath past the terror constricting my throat. I’m not going to die down here. Not yet, anyway. A numb resolve settles in: I can do this. Trying to eject a dead guy out the end of a tomb-black tunnel while you’re flat on your belly feels like a sadist’s idea of a stunt on some nightmarish survival TV show. I push until my biceps blaze, but it’s impossible to get any traction. I might as well be trying to strongarm Atlas’s Dick, a colossal stalagmite cavers use as a waypoint in one of the Brotterling’s upper chambers. I strain and curse and hyperventilate. Drink tears and cold, musky sweat. The white noise churning through the headphones under my helmet provides an incongruous soundtrack to my struggle: monster breakers shattering on a raw, rocky coastline of black sand and a harsh sun (at least, this is the image I get of it). The sound’s meant to protect me from the singing, but right now—pinched like a thumb in a pair of Chinese handcuffs—the buffering noise only intensifies the terror of being stuck in a limestone tube with a corpse. Desperate, I decide to wiggle back out and look for another way to go on, but the tunnel twists and contorts at excruciating angles. It’s impossible to slither out the way I came in. All I get for my efforts are bruised elbows, torn knees, and the mother of all wedgies. Panic claws at my throat. I’ll never get out. I’ll die here, squished inside a stone straightjacket. But the voice in my head bullies and curses me onward, so I crawl back to the body. Since I’m not strong enough to rely on brute force, I devise a slow, minimalist series of tweaks that gradually loosens this obstinate flesh-cork in its stone bottleneck: nudge, twist, rock side to side, nudge again. The poor son of a bitch must have died two to six hours ago, because rigor’s setting in, which helps me extract him. He’s plank-stiff and (I discover later) both arms are arrowed out in front of him like a cliff diver, the body so rigid by the time it finally pops free, he could double as a javelin or a maypole. I wriggle out, shaking and sweat-slick, and aim my lamp down at the dead man, groaning when it illuminates the back of Mamoudi’s seamed, bloodied neck and reveals the muddy helmet to be a porridge of gray matter and hair glommed around a split, trepanned skull. I picture Mamoudi frantically trying to birth himself out those last crushing inches of squeeze, the irony of a rockfall shattering his skull just as his head poked free. It’s a reasonable theory, except that I don’t see any fallen rocks or broken stalactites to back it up. Looking around, I find myself in a wide, high-domed chamber forested floor to ceiling with dripstone. Farther back, overlapping ledges of white limestone crease and crinkle like bolts of brocade. The scene is enchanting and eerie, a grand Gothic hall carved out of calcite and ornamented with aragonite blooms. At one end glimmers a deceptively shallow-looking pond where eyeless albino salamanders laze on its mineral shores. I know from the survey map this is a sump, the entrance to a flooded tunnel leading into the next chamber, but whether it’s swimmable without a rebreather, I won’t know until I’m underwater. Before I can ponder this or Mamoudi’s demise any further, something more compelling than mere violent death snags my attention: a rapid-fire spitting of sound energy, like a mad tattoo artist bedeviling my nervous system with rhythm rather than ink. The energy natters against my palms and wet-kisses the space between my breasts. I get a sense of its volume and pitch, the aural equivalent of a blind person reading Braille, and I’m lashed with fear and euphoria. Although I’ve come down here to find Pree and the others, I also want to locate the mysterious noise. Boone must have realized that too. It’s why he didn’t want me to go. Displaced air caused by something big lunging out of a passageway makes me whirl around. A frenzy of shadows spills over the chamber as my lamp illuminates a surreal sight: Bruce Starkeweather, his naked torso smeared with geometric designs painted in cave dirt and gore, brandishing three feet of a blood-streaked stalactite. His shell-shocked stare tells me all too clearly I’m nobody he’s ever seen in his life, and my death is all he desires. As the sound energy from the faraway singing swells over me, he raises his club and charges. “You should wear headphones to block out the sounds,” I’d told Boone and the others less than twenty-four hours earlier. We were in a small conference room in the Timber Hill Lodge outside Kremming. A map of the known parts of the cave system was tacked up on a board, the shaded areas indicating parts not yet surveyed. Mamoudi and Pree sat together, guzzling coffee and wolfing down bear claws, while Starkeweather, ascetic as ever, stripped foil off a stick of Wrigley’s. Boone, unshaven and haggard-looking, had just come from the hospital where Lionel Hargrave was recovering from a concussion. He told us Hargrave had described his brother’s manic insistence on finding the source of the singing. In his deafness, of course, Lionel heard nothing and, probably for that reason (and because he evidently had a thick cranium), had survived to talk about it. At my remark about the headphones, Pree laughed. Boone looked away, and Mamoudi got up to refill his and Pree’s coffee mugs. I couldn’t entirely blame them. I was technically there as backup, but since I’m also the newest member of the team and never found time to get my cave diving certificate, my inclusion in the expedition was unlikely. Pree, looking fetchingly peeved, said, “How do we communicate if we can’t hear? What are we supposed to do? Use sign language? Text?” Starkeweather mimed headbanging. “Maybe it’s a death metal band down there making people go batshit. That used to drive my old man insane.” Met with such thoughtful responses, what could I say? I wanted to point out that noise isn’t always benign, that whatever’s down there might be the aural equivalent of lobotomy picks jabbed into the brain via the ears. But it’s only a feeling I have, and this group, Pree especially, is not into feelings. Starkeweather asked a question about the survival kits, and while Boone was responding, I went outside and paced alongside a thin strip of forest next to the parking lot. After a short time, Pree came up beside me and tried to slide her arm beneath mine. I swatted her off like you would a pesky mosquito. Only a few hours earlier, she’d stopped by my apartment to try to rekindle some romance. We’d smoked a joint, laughed about old times. Then she took everything off except Mamoudi’s engagement ring and made love to me like I was the last woman on earth. And I let her. Figured I’d hate myself for it later. Seemed like later had come sooner than I expected. “Seriously, Karyn,” she was saying, “if anything goes wrong down there, if there’s a problem, Issa and Bruce and I will deal with it. We know the Brotterling, and we know what we’re doing. So, don’t try anything heroic.” She should’ve stopped there, but she added, “I know it must be tempting, you with your superpowers and all.” I glared and walked faster. “Okay, sorry. It’s just that hearing sounds through your skin, that’s pretty bizarre.” That’s one word for it. It’s also a gift, this intertwining of hearing and touch, where sounds can be physically felt as everything from a shy tap to a punishing blow. It’s a door into something most people never experience. Pree’s voice, for example, feels lemony, tart. It fizzes under my nails and buzzes up my spine like spikes of Kundalini flame. Intimacy enhances the effect. Pree’s voice used to give me not just sensations but images, too: a fire crackling in the kiva of a house that must be from her childhood in Gallup, New Mexico, a young Pree popping figs into her mouth outside an adobe church, and a pale, bearded man who cooed to her while he lay over her body and pounded. My skin drank her life in through her voice. None of this, of course, I could tell her. “Bizarre’s not the word I’d have chosen,” I said. “But when you put it that way, I feel so special.” “You are special, though, aren’t you? You got written up in that magazine.” She was talking about a story that ran in Scientific American (June 2008), in which I was tested along with a number of other more “traditional” synesthetes. Some heard colors; others tasted or smelled numbers and words. An anomaly even among anomalies, I was the only one who could pick up tactile sensations and images via sound waves, even when I didn’t understand the language. “Aural imagism,” the writer of the article called it. I sat with my eyes closed and listened to a woman recite the same passage in a foreign language over and over. Later, I learned it was Finnish. Her vocal tones prickled the soles of my feet; it felt like dancing on tiny ball bearings. The vibrations of her voice formed images like patterns in a turned kaleidoscope. I described a dark red cup, a yellow rose, a strange bird on the wing. The man doing the testing glanced at his notes and paled. The speaker had read a quatrain from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, and I’d just described the primary imagery. Pree laid a hand on my biceps, but I flinched, holding on to my indignation like it was a winning lottery ticket. I said sullenly, “Boone’s screwing up not to send me down with you. I’d be able to feel the singing before the rest of you even heard it.” She sighed and fell into step with me. “Look, Karyn, you’ve been inside plenty of caves. You know what the silence is like down there. Gigantic. A void you don’t want to fall into. Then all of a sudden, you hear something so spooky and so unexpected, you just about crap in your pants. If you heard it topside, you’d know it was nothing, maybe the caver in front of you farted or dropped a carabiner, but underground, it’s terrifying. Most cavers shrug that stuff off, but some people can’t. They have panic attacks; they hallucinate. For all we know, what Hargrave heard was a colony of bats or maybe a few million cave cockroaches.” When I didn’t answer, she snapped, “Dammit, Karyn, are you even listening?” (More intently than you can imagine.) “Maybe Hargrave went crazy because the singing he heard was too beautiful,” I said. “What are you talking about?” “There’s a line in the Duino Elegies by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. It’s something to the effect that beauty is the beginning of terror we can just still stand. Maybe that’s the deal with the singing. It triggers a level of terror humans aren’t meant to endure. It’s too beautiful.” Her mouth set in a pinched line. I thought she was going to slap me. “Nothing’s too beautiful. That isn’t possible.” Then before I could argue, she gave me a punch on the arm that was too hard to be play. “Don’t worry, Karyn; it’s gonna be fine.” She looked back toward the motel as though somebody there had just called her name, although nobody had. She said, “See you on the surface, babe,” and hurried away. Right now, as the sound energy of the singing floods into me and Starkeweather charges, that surface Pree spoke of might as well be on one of Jupiter’s moons. Starkeweather halts just short of the sump. He spits out a lump of gum, bares his teeth in a cannibal grin, and takes a few warm-up swings with the club. I think he’s going to pound me to mud, but to any real caver, what he does next is unimaginably worse: he starts attacking the cave itself, swinging viciously, destroying elaborate lacework and yards of dripstone that have grown at a rate of a half inch per century. Clusters of wedge-shaped helictites explode overhead; stalagmites as tall as a man shatter and crash into the sump. The destruction sickens and horrifies me. Within seconds, something sublime and ethereal has been reduced to an empty mouth full of snaggled teeth. Starkeweather, surveying the rubble, cocks his head and does a bizarre little jig, like he’s shaking off a swarm of cave spiders. He shimmies and scrapes at his face while his lips form the words Shut up! Make it stop! When his eyes refocus, his red gaze finds me again. I switch off my headlamp, and the world floods away in a torrent of black. I drop to the ground and start inching along the cave floor. The headphones are a real hindrance now; they prevent me from hearing which way Starkeweather’s moving. The only sound I can feel is the singing, and that has receded to a shivery caress, a centipede skittering over my eyelashes, a salamander disturbing the roots of my hair. A hail of stones peppers my back and pings off my helmet. Suddenly, Starkeweather’s big hands paw at my legs. I kick out blindly. My boot thuds meaty groin. Then he’s on top of me, spearmint breath hot in my face, mud-slick fingers fumbling for my jugular. A blacker, thicker shade of night starts shutting down synapses, accompanied by a dazzle of sizzling white stars expiring behind my retinas. Under my hand I clutch a slab of smashed dripstone and heave it in the general direction of his head. He releases my throat but then latches on to either side of my mouth and tries to unsocket my jaw. I bite down on a finger until my teeth close on a nugget of bone, then roll away as blood fills my mouth. Next thing I know, I’m underwater. The sump’s frigid and inky, and— Starkeweather be damned—I switch my headlamp back on. I’m inside a flooded tunnel where so much silt has been stirred up, it’s like swimming through horse piss. I look for an air pocket overhead but can make out only jutting mineral walls and the segmented bodies of albino worms ghosting behind swirls of particled water. My lungs bleed for air. The sump narrows into a long, jagged throat, where beyond, water splashes over a pale, fluted ledge. Between me and the air glitters a gauntlet of stone cudgels and knives. My cave pack rips off and my oversuit’s torn. Dark red snakes squiggling too close alarm me until I realize I’m batting away my own blood. My head punches the surface, and I heave myself onto a milk-white dome of flowstone, then collapse across it, teeth wildly clattering. Eventually, I rally enough to fill my hands with rocks and wait to see if Starkeweather follows me. A short time later, he pops to the surface floating facedown. I let him stay like that for five minutes before I grab his belt and haul him up next to me. His neck and cheeks are grotesquely ballooned. When I turn him over, jagged pebbles and mineral chips mixed with shattered enamel gush out of his mouth in a torrent of red. I want to think Starkeweather was already dangerously unstable and would have acted out sooner or later, but I don’t really believe it. I know the singing has unhinged him to the point of attacking the cave with his teeth—the same sounds Mamoudi and Hargrave must have heard, and that Pree, if she’s still alive, is hearing right now. It feels stronger and a helluva lot closer than it did before I passed through the sump. Those previously faint waves of energy are now sharp and urgent, a persistent scratching at various parts of my body, like a frantic child seeking entry to a house at one door and one window after another. But the images accompanying the sensations aren’t so innocuous: a debased horde of humanity crammed into a stadium of bleeding, cruelly crushed bodies, on their knees weeping and howling. Heads thrown back, ready for the knife, keening mad invocations to an obscene deity. Their blood soaks the earth, out of which bloom stone flowers brimming with nectar and death. The vision claws at my heart and I hear my own voice telling me to get moving, to find Hargrave and Pree and get out. It’s hard to obey. I go on. The next chamber confounds me: a sprawling catacomb dripping with soda-straw stalactites and mounded with nodular masses of calcite popcorn. Crystals of moonmilk, a carbonate material the texture of cream cheese, festoon the floor. None of it corresponds to any maps I’ve seen. Even worse are the braided mazes of lava tubes offering a bewildering array of possible paths deeper into the cave’s interior. But the cave, in its infernal sentience, appears to respond. The energy of the singing amplifies, the frequencies becoming imperative, like the head of a silky mallet pinging a flesh xylophone. Letting it guide me, I scramble up a succession of ledges to access a passageway midway up the wall. Its coiled path empties into an angular chamber that resembles a vandalized ossuary: stone pillars surrounding a scattering of femurs, ribs, clavicles, and fragments of skull. That the bones have lain here since long before cavers first discovered the Brotterling is made clear by the centuries-old webs of calcite deposits that veil them. I pick my way through the boneyard as quickly as possible. Beyond it, my headlamp illuminates the area from where the sound energy seems to emanate—a lavish display of boxwork about four feet overhead, where calcite blades project at angles from the cave walls, creating a dense and elaborate honeycomb. Between the mineral blades gleam dark seams, fistulas of ebony pulsing like fat heaps of caviar that vibrate with an avid, luminescent life. Fine, blood-red webbing threads through the black, a network of alien capillaries that carries not blood but warm, coppery sound—it seeps under my scalp and teases behind my ears, seeking to peel back and penetrate the soft, vulnerable creases of brain. If I get out of here alive, I know what I’ll tell Boone: the singing’s not random or chaotic; it has distinct meters and color tones, and it pulses with dark languor underlaid with vicious intent. I will tell him the creators of this song are not human, but not unsentient, either. And if the term life-form applies to them at all, it’s a life in service only to the obliteration of all others. Long stretches of spellbound time pass as I stand here, watching the tiny caviar mouths pulse and burble out a black saliva of sound that feels ripe and almost sexually decadent. Avid and succulent and, yes—Mathew Hargrave nailed it—delicate, too. I want to slather my hands in the mineral meat between those basalt blades, squeeze up fistfuls of its alien iridescence and lather it into my pores, let it replace all the blood in my body with its unholy wails. I take off my helmet and hurl it away. Then I reach up to remove the headphones. And stop. Above me, imbedded into the hivework, loom strange columns worked into the stone, skeletal formations lifting toward the obsidian sky. Sections are patterned with ovoids and creases of lighter stone, the pale areas inlaid with vertical striations of crimson. The sight wallops the breath from my chest. One of the columns is watching me. Basalt doesn’t bleed, but burst eyeballs and lacerated skin weep red down the sides of the dripstone cloaking two human forms in their mineral shrouds. Mathew Hargrave has been almost entirely consumed. Crusts of muscle and gashed bone jut out from his stone sarcophagus. Only his upper chest, the arms tucked into his torso like folded wings, and his slack, swollen face are still recognizably human. His remains are being played like a bone flute as torturesong rasps from his mouth. But Pree, oh Pree, is another matter. Her time inside the Brotterling has been briefer than Hargrave’s; less of her has been entombed. Rigid and ashen-faced, she balances on a narrow outcrop a few feet above, tarry squiggles of hair falling over the rags of her clothing. Her mouth convulses in torment. Skeins of sound tangle in her teeth and snake from her lips. Tendrils of it adhere to her face. The frequency of the vibrations chugs to the lowest registers, rich and mellow, bassoon-like, the notes unspooling in hypnotic spirals, so that each births the next lower note on the scale, and all the while, Pree’s terrified eyes tell me the truth: it’s a death song and she can’t help but sing it. Black rings frame the edge of my vision as Pree’s silent screams flail me. Her body spasms. A rent opens under her breast as the slender spear she’s impaled on exits her chest in a gleaming red fist. Behind two snapped ribs, I glimpse a gray, pulpy thing beating feebly. The ledge is slick and cushiony, weirdly flesh-like, when I climb up, wrap my arms around her, and try to lift her free from the stone. Crimson bubbles erupt from her mouth. She tries to form words. I put my face close to hers as she exhales. Her death-rattle breath goes into me like an intubation tube, rancid and chokingly floral. There are no last words, no blessing, just a sob that’s a truncated ode to damnation as she bleeds and convulses in front of me. And I leave her. God help me, I abandon her there and begin the torturous trek to the surface, a wet, nasty, soul-crushing ordeal, while with every step, I expect the cave to crush or consume me. Most of the way, when I’m not using my hands to climb or to crawl, I clutch at the headphones, terrified they’ll fall off and the singing will overpower and annihilate me. Yet despite hours of exhaustion and terror, somehow I prevail. The passages, in fact, seem to widen as I pass through, the skin-you-alive cold of the sump is less heart-stoppingly frigid, the waypoints more easily spotted. Even the terrifying Bypass, outside of which Mamoudi’s body still sprawls, feels smooth as a tube and excretes me effortlessly. When I finally reach the surface, blinking and bedazzled by the afternoon light, a small army of cavers, media, and National Guard are assembled, as another team of cavers prepares to go down. Boone’s there among them. Seeing me alive, his eyes well, as do mine. I tear off the headphones and sweet sound rushes in, the wind whistling, a truck backfiring, the crowd erupting into ecstatic cheers to see someone come out alive. Then they get a good look at me and my appearance—soaked, shivering, smeared with cave dirt and blood—shocks them silent. As one, they reel back. Finally the braver ones gather their wits and being firing off questions. What happened? What’s down there? Is anyone else still alive? But these are not words the way I remember them. What I hear is a saw-toothed cacophony, an unwholesome chorale—discordant, repellant, impure. I want to rush back inside the cave to get away from their cawing, but I remember that first, I have something important to do. I must warn them of the terrible danger, so I focus my mind and conjure the sounds I will need. When I know what I must say, I run toward Boone, who is already beckoning me. I scream, Get back! Get away from the cave! Everyone inside is dead! But that’s not what comes out. An excruciating hitch unlocks in my chest as an arcane melody, a kind of cryptic trilling, slithers free and soars to the winds—the feral and wondrous, delicate song birthed from the mouths of monsters, from Pree’s mouth into mine—into theirs. Madness made tangible. Contagion by sound. It spews from my lips—a song of such deadly beauty and unholy allure that I experience only the briefest frisson of horror—an emotion something inside me instantly quells—when their mouths fall open, songstruck, enthralled, and they begin to rend their own flesh and tear each other apart. I understand this is how it must be. I go on, unfazed by the carnage, undeterred by the din. For I am the throat of the Delicate Singers. In the cities, the towns, in the streets, and beyond, I know others are waiting to hear me.