#pceswatini

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Learning to Learn—A Day in the Life

Life is. God is. Love is. I have found that the best things in life are often times indescribable in nature; sure, attributes and characteristics are easily noted, but the heart of the matter is not to be spoken on so much as felt. We know they exist because of how they make us feel, and how alive they are in us and around us.

Long before I came to the country of eSwatini, long before I even decided I wanted to join the Peace Corps, I made the decision I had to get out of the United States. America, as some would call it, for all it’s glorious opportunities, was little more than a overused and outdated ideal that fostered little more than coerced silence and disillusioned bitterness from it’s citizens. I felt that I for one was suffocating, screaming with words trapped in collapsing lungs; I was desperately trying to breathe the air of a freedom I could not find in my mother country. Around the time that I realized that because of the color of my skin, because of my radical convictions and unapologetic perspectives I would never be accepted in America, I almost immediately wanted to belong somewhere else.

It was in this season of my life that I began to read like I never had before; intensely, feverishly searching for an answer. In all honesty, I never exactly found what I was looking for; well, I mean, I never found what I was looking for in a book. Despite this, that time in my life planted a seed. That seed would grow into a burning desire, which eventually became my becoming a Peace Corps volunteer in the country of eSwatini (Swaziland), Africa. It was not until I arrived in eSwatini that I felt the closing of a full circle, and the beginning of a new journey with new questions and new lessons to learn. Now, a new seed was planted in me—maybe here, in this country, I can belong to the land, the people; maybe here, in this land of Black people, I can taste the air of liberation.

After a few days of settling in with my cohort of 46, including myself and my wife, we began our training prior to our official Peace Corps Service (Pre-Service Training, PST). It was the beginning of a 3-month-long training process that included technical, medical, cultural, diversity/inclusion, security, and personal mental health trainings in order to prepare you for service. The stakes were high—do well on your assessments, and you stay in country and move on to your service. Do poorly, and you risk returning home. When we first arrived in country we lived in a dormitory style apartment building, and would walk the breezeway to our conference room to begin trainings around 8:00 am. A few weeks later, we moved to our temporary in-community homesteads as a means of further integration and preparation for our permanent sites.

The first month was definitely an adjustment—no access to running water in our home, with home consisting of one a room house that wasn’t big enough to house much more than our (Angel and myself) luggage, a queen-sized bed, and a table. Despite these minor inconveniences, we had a very loving and helpful Make (mother), Make Mdaka, who made sure every day we were fed and not late to our morning language classes. She also had a very sizeable homestead (the property that she owned which constituted a chicken coop, two planting fields, a garden, and several avocado and banana trees) which had three houses, including our own, and one house which had both running water and electricity which we were allowed to enter and use upon request. Honestly, we kind of had it made when it comes to temporary sites.

Other than that, our daily schedule generally was as follows—

5:30 am- Wake up and do morning routine (iron or steam clothes; pack bags; make breakfast)

7:00 am- SiSwati language class (Sentence structure; vocabulary; verb tense; sentence construction)

9:30 am- Ride Peace Corps transport to training site (IDM or SIMPA institues) for technical, security, diversity, etc. trainings

4:30 pm- Ride bus home to temporary site

5:00 pm- Settle in at home and begin evening routine (Boil and filter water for drinking; cook dinner; practice siSwati with Make)

7:30 pm- Watch a few movies or tv shows on hard drive

9:30 to 11:00 pm- Call it a night and get ready for the next day

I would say that one of the biggest challenges I have faced in my time here is learning to learn, over and over again. No matter how much you know about yourself, other people, other cultures, institutions, whatever, you must put yourself in a constant space of being willing to learn again. Whether it’s the ways of the culture, the language itself, the nuances of etiquette, or a simple trip to the store, this experience of intrinsic learning has been constant ever since my arrival. Blackness, as another example, for all it’s beauty and diversity, is not a monolith. Though I have loved connecting with umdeni wami (my family) in the African Diaspora, especially in the Motherland of Africa, it would be dismissive of me to not acknowledge there are differences between us. Furthermore, it has been challenging addressing questions that come with the nature of our being in-country as volunteers— “Are you a spy?” “Donald Trump does not even like Black people. How did you get this job?” “Why is it that volunteers always come here, but we never have volunteers go there?” “Can you just give us the money and we can do it ourselves?” The realities of imperialism and capitalism, and their effects, are felt on both a conscious and subconscious level by all involved parties at all times. Yes, we are both Black; No, we are not exactly the same. In some ways we are worlds apart, and my being here could potentially inflict as much pain as it could help. Being able to see that not unlike the missionaries and colonizers which once (and still do) settled in this country, that I can inflict damage to the self-perception of the people of this beautiful country and what they perceive as their ability to create and find solutions to concerns in their communities, is a very sobering reality.

That said, there are times of bonding along the lines of shared experience that are utterly indescribable. It is beautiful witnessing the ways in which Black people have connections across ethnic cultures that are practically impossible considering the span of space and time. And yet, there are signs—the dancing, the rhythm, the love and compassion, the viewing of time as fluid and humanity as intricately connected with Nature— and ways of life that are deeply embedded in the fabric of Black people despite being separated and unbeknownst to either people; this, for me, is both humbling and encouraging. Despite what we may believe in the States, Black America is not too far off from the Mother and her ways.

There have been learning curves too, interacting and fellowship within our cohort. No group of people is perfect, so long as there are people in it and our group of 43 volunteers is no different. Egos, destructive criticisms, and back-biting are all possible realities of strangers coming together to accomplish any goal. We decided as a group that our cohort name would be Simunye (meaning “We are United; We are One” in siSwati), but the chemistry of our group has not always been one of unity (and still isn’t…it’s a process). For me, coming from an HBCU undergraduate background and a very ground roots racist, institutionally neoliberal PWI for graduate school, I initially had my reservations concerning connecting with people whose backgrounds I do not know and intentions I cannot always perceive, especially White with people. Despite these prejudices I had, I have come to understand and believe that through vulnerability, transparency, patience, perseverance, and a willingness to change, even the strongest of boundaries and borders and be taken down with the strength and unity of love. We are all capable of causing each other great suffering, but because of this we are also able to bring about great healing and through that healing a greater community and a stronger bond through our shared humanity. This, for me, is a lesson I am yet learning but a journey I embark on happily (I’ll talk more about this later on!).

So I’m saying all this to say…it’s been an adjustment. There are things that are similiar, and there are things that are not. Just like everywhere. Every city, every place has a song in it’s heart; the trick, the question is “can you catch the rhythm?” When I first arrived in country, I thought there were things that I knew; now there are things that I don’t know. I am learning to catch the rhythm. I am learning to learn, again.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Create Heaven Here—My Story

For the record, this probably should have been the first “official” post for this blog. My bad, I’m a learn-as-you-go type so I’ve been messing around and BOOM well, here we are.

*clears throat* ahem...

When I was young I wanted to be a writer. I always dreamed of being a writer; of my words mattering to someone. The unique ability of being able to eloquently articulate thoughts and touch someone else deeply was nothing short of a poetic wonderland in my childhood imagination. Now I am older, and I realise that words, these words are all that I have to give. I once believed that this was not enough; that the sum of who I am had to add up to more than what I can say about this life, or what I have seen of it. I now understand that it does not have to be more than this so much as it has to be true, no matter if the impact of those words is great or small. I am writing this because I wanted my first post in country to be about me; here I will paint an in-depth portrait of who I am and why I am here.

________________________________

It is a common theme in stories originating from the continent of Africa that history is intertwined with mythology, and so too the story of my life is told. Before I was born, my father wanted to name me Shaka Zulu in honour of the infamous, Southern-African warrior. My mother protested, worried that I would endure ridicule and shame because of a lack of understanding from other children or teachers. And with that wisdom, I was instead named after her, Desmond—the son of Desiree. If only they had saw fit to ask the Creator to not give me the soul of a warrior since it was decided I would no longer be receiving the name. I was born with asthma. Mom would later tell me that it was because even before I was born the evil of this world wanted to steal my breath, to take my words.

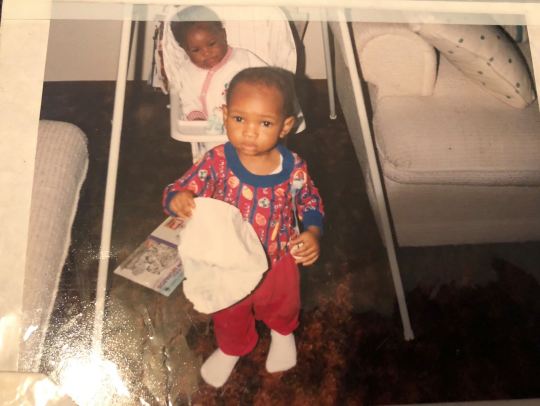

In early childhood, I found it hard to have a voice for myself. As a matter of fact, for the first year and a half of my life my parents did not think that I could talk at all; my older brother, Gerald, would always speak for me. Whatever he liked, I liked; whatever he wanted, I wanted. It wasn’t until one fateful Sunday School class where there was an option of cheese or peanut butter and jelly crackers that I had spoken publicly at all. With whatever self-esteem I could muster up in my infantile body I stated very clearly, and to the surprise of all in attendance, that I wanted peanut butter and jelly crackers. That would be my first fight; my brother wanted me to have the cheese crackers. From then on my life would be a series of advocating for myself or on behalf of others, and willingly paying the price no matter the cost.

I got into a good number of fights as a child. I was more passionate than I was “boy”. I had a spirit of fire and wind; free, scorching, and bold. I went from unspeaking and timid to outspoken and determined. Dont ask me what I was determined to do, though. To this day, I do not know what I was so serious, so keen on grasping at prepubescence. I was raised in the church like most Southern Louisiana, Black boys. It was here that I was able to find comfort and a sense of pride. Along with the classroom, the sanctuary was a place where my words were accepted; it was a place where intelligence and passion could meet, and where adults were impressed and were quick to take promising young pupils under their wing. Many teachers spoke highly of my performance in the classroom, and so did ministers at my place of worship. Unfortunately for me, there was a great degree of protection that was in the church setting that was not remotely available in an inner-city elementary school with a magnet component.

I could never understand at the time, from the background which I came, why “Church Boy” was an insult. Honestly, it didn’t bother me so much as the implications that came with it. Implications like that I could not defend myself; that even if I could not, that I had parents who would quickly take up for me; that I was weak and afraid of a world that was unknown to me; that someone else had the right to take these things from me. These statements were made between curled lips and clenched teeth and clenched fists; from smacked lips and cold stares I learned that having two parents in one home and having an identity rooted in church life were things to be snickered at. With those snickers came threats, boys posturing themselves to be perceived as men; willing to play at absolute dominant power in the face of what seemed like a helpless Christian kid. And with that, I let those assholes eat my fists. Never one to back down from a fight, I got in more fights in and out of school between my elementary and high school years than I care to remember, in and out of school. I lost many of them, I won some. One thing I never did was back down. I would be felt, I would be heard, I would be respected.

This philosophy came to frustrate my parents who constantly reinforced a message of choosing battles. Though I felt an angst from the outside world, there was no difference in emotion concerning the place that I called home. My mom has always been a jewel in my mind; her beauty, poise, and radiance will never fade and will always be priceless. My dad, my protector; a strong tower and defender of his family, which for him was his pride and joy. En lieu of these praises I now sing, the truth is as a child I felt very much alone and afraid. My dad would often invalidate the words I would say as foolish or thoughtless, and it was a rare sighting for my mom to protect my emotions from his aggression in those moments. Mom was an artist in her day, and I would say very much so an existentialist. She taught her sons to feel, and to feel deeply the offerings of this life; what a gift this is, and it is one I will forever be grateful for. But, what a curse this was, when under the weight of the absolute terror that is an emotionally insensitive parent. As if the words and insults of a man you see as your protector and provider were not enough, the inexplicable silence of that other person who built you as this fragile human being made for a combination that never ceased to knock the wind out of me.

Even in sports, which I did not particularly excel in for some time, my brother and I were not seen by other players as much more than the coaches’ sons. With this came the same insults and curses that I experienced at school, but only this time in an environment of high passions and high volatility. Myself, being the more hotheaded between Gerald and I, always took the bait of these insults only to be publicly humiliated by my dad once word reached to him. It was inescapable, this fog of perpetual pain that occasioned seasonal rays of artistic expression and raging passion that served as my outlets. The one haven, the castle on the hill in this experience was the church. I was a child that was made vulnerable to everything, and therefore I felt everything. This eternity of feeling left me ragged and tired of many things, and as a result I became a very cold and methodical young man. I became what others would refer to as “mature” and “wise beyond my years” or “strong”; I never wanted to be any of these things. I never wanted to be strong, I just wanted to be safe.

Through sheer determination and willpower I did well both academically and athletically in high school. I graduated, and went on to undergraduate studies out of state. More than anything I wanted to leave behind Louisiana and it’s incessant ignorance and backwards logic; how wrong was I to think that it was a regional issue. I decided in college that I wanted to be a different person, a more visible leader and advocate on behalf of myself and other. I think it was this thought that guided me to make a vast majority of the decisions I would come to make, both good and bad. I would hold a few positions on campus and ran track my first two years of college. These points are not why this era in my life matters, though. It was here that my life would first fall apart, and largely because of my own doing. Somewhere between my university studies and my out-of-class experiences I no longer believed God had an active role in my life. I mean sure He was up there and guided me to the school in the first place, but looking back on my life I did not see a reason to believe that there was this ultimately powerful being who had been looking out on my behalf; again, the God I knew made me vulnerable, transparent to a world that sought to destroy my faith in it and in Him at every turn. If that was the God that had been watching me since birth I wanted nothing to do with Him, or, rather, I think we needed to spend some time apart.

And so, I lived my life and I lived it grandly. Unashamedly infatuated with luxury, opportunity, and prestige, I was well-known on campus; in some ways, I was notorious on campus. Eventually, that notoriety caused me to make some ridiculous college kid decisions, as most college kids do, that almost had very adult consequences. Regardless of what did not happen, one particular situation had consequences that resulted in a very loud, very public fall from grace; I was ashamed. That summer, on my annual return to Louisiana, I was broken and lost. I felt alone, embarrassed, and trapped, not much different from how I once felt as a child. It was in this season that I began reading Thich Nhat Hanh and meditating. I began shaving my head, a sign of consecration to a purpose I had long thought I lost or forgotten, and cut all meats out of my diet except for fish.

Yet embarrassed because of the terms on which I left the university, I told some of my peers and fraternity brothers that I more than likely would not be returning. The weight of the guilt and reliving the chaos of the preceding year seemed too much to bear. In the midst of these thoughts came the same soft, cool, all-consumingly overwhelming feeling that led me to the institution, initially. In that moment, to my soul came the urge to return and that if I were to not return I would be a coward. “What has kept you, will not sustain you”. Those words, words that came, in my opinion, from the universe directly to my spirit were the words that I rode all the way to Nashville on a 12am Greyhound bus.

In this final year of university, I discovered more about myself that I can explain; who I was, who I was not, who I wanted to be, and who I was willing to become. The magic of the moments in that year seemed to meet me in roaring waves of enlightenment and revelation; I was alive, fully alive for the first time. In this season I began to see the early formations of a personal philosophy that would become the cornerstone of a dream—a dream to create my own reality. It would be this dream that would propel me to achieve another lifelong dream of mine: becoming a Peace Corps volunteer.

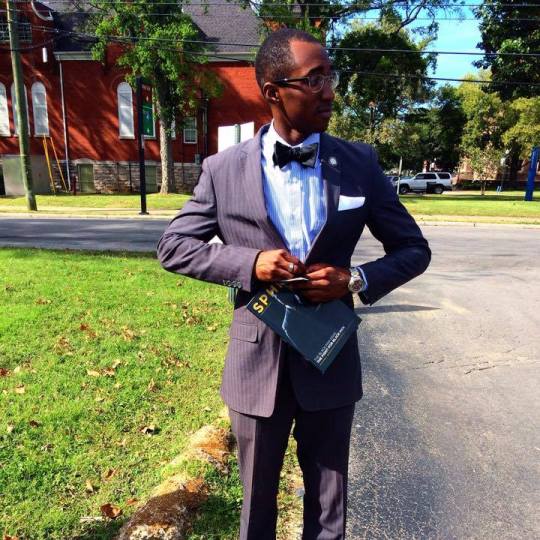

Peace Corps was, and is still, an opportunity for me to connect with people world’s away; to learn their language, their ways of life, what life means to them, and what love means to them. For me, this was, and again still is, perfectly in alignment with who I wanted to become and had been a dream for me for quite some time. Well, after finishing my undergraduate studies, a two year completion of graduate studies back at home, and a marriage-to-my-best-friend later, I and my partner were granted the opportunity to become Peace Corps Volunteers in eSwatini (Swaziland). After months of training, going from Septemeber 27th to December 12th, we were able to be sworn in, officially, as volunteers of the United States Peace Corps. These past few months have been riddled with their own, unique challenges. Viewing life as an adventure helps me to make light of these experiences, and to examine them objectively, in the grand scheme of life.

The experiences I have had the blessed opportunity to be a part of and the future experiences I will have the chance to live and feel will be documented and scribed here for two main purposes: to tell a story that often times is not told; the story of the Black male minority, who has a rare opportunity to go places that many other Black people may never have the chance or the courage to. The second purpose, is to be transparent about the hard work and the beautiful struggle that is connecting, living, and loving other human beings. Despite the difficulties, despite language barriers, despite whatever obstacles, I believe that all people seek peace and connection, wholeness and reconciliation. It is this belief that has guided me, that has become my personal philosophy, and that continues to guide me.

To close, I refer to the Biblical passage of the story of the Tower of Babel; all of humanity came together with the grand cause of building a tower to reach the heights Heaven. Not only were they successful in their united endeavors, but so much so that the hosts of Heaven feared that humanity would ascend into the Heavens because, when they were united, there was nothing they could not accomplish. As a result, humanity was called to speak different languages in order to cause division and confusion amongst themselves. I am here, and walk this Earth, with the intention of rebuilding that tower; or rather, to bring about the revelation that Heaven was the ability to have peace and love, united in a cause for the benefit for all of humanity.

Once there was an endeavour to build a tower to reach unto Heaven. Why build up when what you truly seek is inside and around you? You do not have to wait until you die; you do not have to wait for an act of God. You are the act of God; your life is an act of God. Come on; let’s Create Heaven Here.

0 notes