#pasuma

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

No end in sight: In a bitter face-off, Pasuma and Taye Currency maintain their position

No end in sight: In a bitter face-off, Pasuma and Taye Currency maintain their position The relationship between Fuji music icons Wasiu Alabi Pasuma and his former protégé, Alhaji Taye Akande Adebisi (popularly known as Taye Currency), has reached a boiling point, with both parties refusing to reconcile their differences. R was reliable informed that both parties will not shift grounds on the…

0 notes

Link

Download Dj Scratch Ibile Ft. Dr. Saheed Osupa & Pasuma – Gbogbo Written by Kelechi Ofor

0 notes

Text

Gangs of Lagos

Gangs of Lagos (Serie 2023) #DemiBanwo #AdesuaEtomiWellington #TobiBakre #AdebowaleAdedayo #AlabiPasuma #Chike Mehr auf:

Serie Jahr: 2023- (April) Genre: Krimi / Drama Hauptrollen: Demi Banwo, Adesua Etomi-Wellington, Tobi Bakre, Adebowale Adedayo, Alabi Pasuma, Chike … Serienbeschreibung: Eine Gruppe von Freunden wächst in den belebten Straßen des Viertels Isale Eko in Nigerias Hauptstadt Lagos auf. Im Laufe der Zeit verstricken die jungen Frauen und Männer sich ein korrupte Machenschaften, wobei Armut, Gewalt…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Asake, Wande Coal, Timaya, Pasuma Others Thrill Crowd At Tinubu’s Inauguration Concert

Many top Nigerian celebrities on Thursday night, stormed the inauguration concert of President-elect Bola Tinubu. The event comes shortly after Tinubu and Shettima were conferred with Grand Commander of the Federal Republic and Grand Commander of the Order of Niger honours, respectively, in Abuja on Thursday. Many Nigerians and All Progressives Congress (APC) supporters stormed the event…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

ASAKE - WORK OF ART REVIEW

“But una know I no dey waste time” is Asake's pre-written answer to questions bordering around why his sophomore album is out barely 9 months after his scintillating debut. Not that anyone is less than thrilled to see him back so soon, mind, but we are all too familiar with the compromises to the production process that may aid an artist to achieve these hurried release schedules. Asake, however, does not sacrifice quality on the altar of speed, so that what is traditionally a sticky point for establishing artists—the second album slump—is turned into a flamboyant, braggadocious display of his extent of pliability of his Fuji-Amapiano creation, and then some.

Doubts have persisted for nearly as long as he has been mainstream of his ability and/or willingness (or lack thereof) to explore music styles outside his patented scope, but Asake does not intend Work Of Art to be a definitive end to this conversation. So while he does push even further from the conventional in a bid to conquer sonic territory, he plants his base firmly in the music that has brought him thus far—the rhythmic familiarity of log drums and shakers, the ethereal resonance of crowd backup vocals and his own euphonic, Fuji-recalling delivery.

For “Yoga”, his 2023 opener which now closes the album, he sets himself sonically somewhere between Indigenous Egun music of Badagry, Lagos and the Sega genre of Mauritius, weaving together diverse cultures. His message here is clear; he is in his own lane and it would be pointless to try and catch him—but this time he goes for sombre self-identity over overarching superiority. Not to say he does not have some of the latter in his toolbox. On “Lonely At The Top”, the track from which this article’s opening quote was carved, he may appear to get ahead of himself—this is, afterall, only the second year since his proper breakout single, and there are others who have secured and maintained a top-flight status for much longer—but Asake’s time has always run a little faster.

That is the reason why, still struggling to find a footing in music and life in general, he announced himself “Mr Money” in his 2020 single of the same name. On Work Of Art, boastful predictions for his future can carry the extra backing of his conquests from last year, and he knows it. On “I believe”, the optimistically upbeat joint which Magicsticks reworks from Amapiano’s log drums, Asake proclaims “Nitty-gritty of ‘22, I’m the one”, casting back to a year ago when he thrilled the country with a conveyor belt of hit singles before his debut album landed the final blow. He rewords and translates this on “Awodi”, stating “2022 mo gbe wan trabaye”, another claim that can be self-promoting without being exaggerative. On this chiefly Yoruba song, his honours Pasuma both in words and in the Fuji-ogling framework the track is crafted on.

Whether Asake’s outsized self-image is primarily a function of belief in himself or trust in a higher power is debatable, but it certainly is some combination of both. He definitely has the spiritual strength to justify the latter, as he embraces, in the popular Yoruba polytheist ideology, both Christianity and Islam, and delves into African Traditional Religion when the situation requires it, when there is need to tie ese ile bo. But where Mr. Money With The Vibe regarded these religions, like most people do, as a means of covering all bases in the search for material upliftment, Work Of Art has Asake transcend beyond this and ponder on the afterlife.

He weighs in turn a Christian (“Mr. Money with the vibe ‘til the devil say my name”) and then a Muslim (“Koni wa le lai lai till we reach Al Jannah”) aftermath, but reaches a consensus in either case that he will live to the full until that moment arrives. And while these musings might seem somewhat premature for a 28 year old man in apparent robust health, Asake has never faltered in his preference of an impactful existence over a lengthy one. So today he will drown in a variety of substances from alcohol to colorado, before burying his head in the thighs of the woman he loves. “Let’s stay all night looking as the star shines/ Make love till the sunrise” he sings on the now-decadent, now-affecting “Mogbe”.

Romance flickers brightly in other corners, even if it is a rare sight on the album and is often easily contorted into lust. “Remember” has a chorus that wants to negotiate affection with money, not an uncommon love language in a country with so little of it. “I wanna love you forever, baby o/ I just want to spend all my chеddar on you”, he says at first, but what comes next unmasks his carnal intentions. “Sunshine” shares all of this blissful radiance, but, without its romantic overtones, Asake intends it to be a pat on the back to the weary soul, equal parts motivating and reassuring. “Sun’s gon’ shine on everything you do”, he says, and if those words appear familiar it is because they were borrowed from Lighthouse Family’s “Ocean Drive” of 1995, and Asake transports this iconic line across time and genre without losing any bit of its eupeptic essence.

Asake uses himself and his incredible journey, as successful people often do, as a guiding light to those still stuck on the lowest rungs of the ladder, but material success is only a small contributor to his euphoria. For Asake, the process is just as important as the result, and like every true artist he prides himself even more in the art that has brought him thus far.

“Basquiat” throws down the gauntlet with the arrogance of a man that knows it won’t be taken up, and while he is aware of similarly sounding artists that the media will try to force into comparisons with him,— “Studying me is an honour jeun lor/ I get many pages like songs of Solomon”—he will superciliously point out the futility in reading a master’s textbook to try and be better than him. “What's the chances, what's the probability/ To see a bеtter version of me with agility”, he asks on the spunky Blaisebeatz-produced “2:30”, but it is only rhetorical. He has his answer.

If he is any worried about deposition, he hardly shows it, and more importantly, he will not let it bog down his brilliant new creation. “Basquiat” is also the closest thing to a titular track on the album, whose cover art is depiction of Jean-Michel Basquiat by Nigerian artist, Ayanfe Olarinde. While Asake sees similarities between himself and the talented, troubled, visual artist, he has long established to have no greater weapon in his arsenal than his individuality and sense of self. A few fans may clamour to see him try on new trends and sounds, but Asake insists that he is the template, the “work of art” that should be studied. And he probably is right. Supreme ability and a unshaking confidence in it are always a devastating match, and his blend of indigenous cultures from fifty years ago and trendsetting house music of the future makes him one of the easiest bets for the next great Nigerian star.

This article was written by Afrobeats City Contributor Ezema Patrick - @ezemapatrick (Twitter)

Afrobeats City doesn’t own the right to the images - image source: Instagram - @Asakemusic

#Afrobeats#Afrobeats City#Asake#Work of art#Album review#Music article#Africa#African music#Basquiat#Nigeria#Nigerian music#music#Afrobeats article#Afrobeats UK#Mr Money with the vibes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Asake Nearly Turned Travis Scott to Pasuma”: Mr Money Interpolates Fuji in New Song With US Star http://dlvr.it/TBc347

0 notes

Text

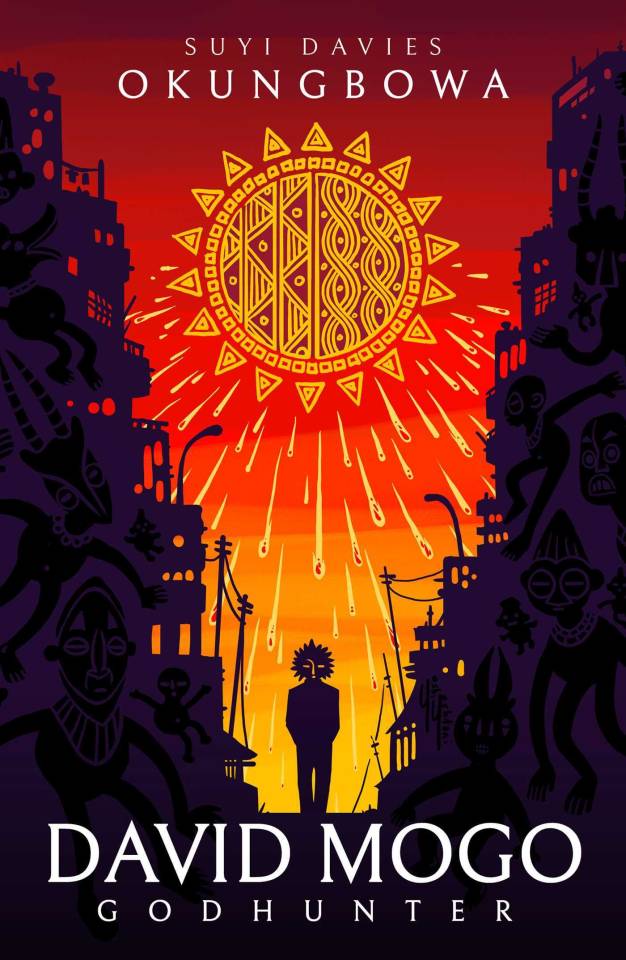

David Mogo, Godhunter by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

David Mogo, Godhunter by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

By: Gautam Bhatia

Issue: 9 December 2019

David Mogo is an ordinary Godhunter, scouring the streets of Lagos to find and capture stray gods in return for payment. For this is no ordinary Lagos: here, the city is populated by gods of all descriptions, who arrived there in an event known as the “Falling.” Now, they dominate one part of the city, which has become a no-go zone for humans. Mogo, a “demigod” of unknown descent, considers himself to be an ordinary guy, surviving in the new god-oriented economy by solving small problems, such as those caused by godlings stuck in water tanks.

But all that changes when Mogo accepts a lucrative assignment from Lukmon Ajala, a local Baálẹ̀, to capture two gods and bring them back to him. During the course of his assignment, Mogo realizes that there is more to it than meets the eye. Before he knows it, he is neck-deep into an ancient internecine struggle of the gods, a struggle whose consequences threaten to spill over into Lagos, and from there, into the rest of the world. It is a struggle that will envelop Mogo and those around him: Papa Udi, the old “divinery” (or “wizard”) who has brought him up, Taiwo and Kehinde, the twin gods he was supposed to hunt but who become allies, his absent god-mother (who turns out to be the goddess of war), and the women and men he meets along the way, struggling to survive in a god-besieged Lagos.

Suyi Davies Okungbowa’s debut novel takes us careening into contemporary Lagos, and the Yoruba pantheon. A blurb reference describes it as belonging to the “Nigerian Godpunk genre.” While the word “Godpunk” comes with its own historical baggage, it is perhaps a reasonable placeholder: Okungbowa writes in a gritty and fast-paced—but eloquent—register (people “cling to the shadows of the evening,” there is laughter like the “clatter of metal sheets in the wind,” and voices like a “whiff of black pepper in the air”); the story tracks the familiar theme of conflicting relationships between humans and deities on (primarily) human terrain; and finally, the conflict is (sought to be) resolved through a military confrontation, where god-powers clash spectacularly upon a human battlefield, in a war that is—quite literally—larger than life.

Beyond some of the overarching themes that place it within the “Godpunk” genre, however, what immediately stands out in David Mogo, Godhunter, is just how situated it is (“Growing up Nigerian, nights without lights are not new to me”). The novel is of the city of Lagos, much like Neverwhere (1996) is of the city of London, or Djinn City (2015) is of Dhaka. This doesn’t simply mean that the novel is set in the city; but rather, that the events of the novel are deeply entwined with the city’s geography (spatial, economic, and social) and daily life. Or, in other words, it is the city that gives the novel its identity, and it is impossible to imagine that novel set anywhere else. Okungbowa accomplishes this with a very rich visual—almost visceral—account of the locales of Lagos, from its lagoons to the airport (visual enough that I kept thinking, while reading, about how good a cinematic adaptation would look like!):

The smell of faeces in stagnant water is still there, overpowering. Papa Udi, Fatoumata, Femi and Shonuga cough and choke, wrapping their palms around their noses. Mosquitoes buzz around us. The familiar swish of lagoon water is a welcoming sound; I��ve missed it, holed up in that airport for months. I get a flash of Hafiz’s orange ankara cloth and Justice’s Pasuma Wonder t-shirt, and realise I’ve missed them too—I should stop by and greet them once we’re done here.

At the same time, however, these are unfamiliar locales. The colonial history of the world, and how we, its inhabitants, are given that world, ensures that (for example) to an Indian like me, the underground stations of Neverwhere will provide an immediate set of reference points. On the other hand, Lagos’s Third Mainland Bridge or the floating neighbourhood of Makoko (both of which constitute spectacular set pieces for some of the significant events of the novel) will not. Importantly, David Mogo, Godhunter elects not to give the reader those reference points: the reader is presumed to know of the Third Mainland Bridge or Makoko just as well as they know of Blackfriars or Islington; and she is presumed to know exactly what it means when the narrative voice wryly remarks, for example, that “trying to get the owners of divineries to band together for a common cause is like asking Hausa northerners and Igbo easterners to come together and eat from the same bowl.”

This is a risky authorial choice, but—I believe—a necessary one: because, if decolonisation is to mean anything, it must surely mean that books of London and of Lagos are read on their own terms, and there is no additional burden of translation upon the latter. In the end, the quality of Okungbowa’s writing, and the vividness of his descriptions make the problem of translation a moot one. Nonetheless, I did think—as I read the book alongside open Wikipedia links to Lagos’ geography—about the unfairness of a situation that requires a novel set in Lagos to either engage in geographic explanations, or be simply so good that the absence of explanation ceases to matter.

There is, of course, a similar issue when it comes to the gods themselves. “Godpunk” novels such as Neil Gaiman’s American Gods (2001), for example, or some of the works of James Lovegrove, are familiar and comforting in their pantheons, because familiarity with the Greek, Egyptian and Norse gods has become something of a lingua franca amidst the cosmopolitan, English-speaking population that constitutes English-language SF’s global constituency. Okungbowa’s Yoruba pantheon offers no similar comfort (in this respect, it is similar in some ways to Marlon James’ recent Black Leopard, Red Wolf [2019]). We begin our acquaintances with Olorun the creator from scratch, Esu the trickster and the god of the crossroads, Ọya, goddess of the river, and many many more. The loss—as we soon realise—has been ours all this while, and there is something quite fascinating (and, dare I say it, magical) in watching a fresh pantheon unfold before your eyes, where the gods (in general) do not act in ways that you expect gods to act, and gods (in particular) come unburdened with the weight of far too many layers of prior, English-language interpretation:

The god’s signature flashes across my consciousness: the beauty of sunset and waterfalls; the smell of raw incense; the sound of water from a fountain; a bell pinging underwater; a chalice—big and beautiful and royal—made for wealth alone; wine, drunk from this chalice, the back of my tongue tasting of grapes, but also of fish; a bleak day of mist and fog, but which is really a dream; the cry of a big fish, calling to its mates underwater. I reach out, heady with nausea, pushing my godessence, asking the signature questions of its origin.

There may come a day, of course, when we know exactly what Olokun will do with water, what the “sponge ritual” really is, and why shigidis exist; perhaps, on that day, novels will be trying to disrupt those expectations, and that will perhaps be the day that SFF is truly decolonized; but until that time, we can perhaps only be grateful that there are worlds yet left to discover, and writers like Okungbowa to guide us through them.

Finally, David Mogo, Godhunter is not just about spectacularly choreographed battle scenes amidst the wreckage of the neighbourhoods of Lagos. It is also a bildungsroman, tracing the interior life of David Mogo from hesitant demigod and general chancer, to one of the protagonists of an epic struggle, suddenly faced with the prospect of bearing the moral and ethical weight of the consequences of his decisions. Through Mogo’s evolving interactions with the people around him, Okungbowa also has the opportunity to bring on to the stage a host of keenly-drawn characters (gods and humans both), forming a network of relationships that is explored by a sensitive—and loving—authorial eye. Perhaps most interestingly, however, Okungbowa chooses to give his villains good arguments as well; so at the end of the novel, there is just that hint of lingering doubt about whether we’ve really been rooting for the good guys all this while.

You couldn’t ask much more of this “Nigerian godpunk novel”!

0 notes

Text

Pasuma and Saheed Osupa performing each other’s song on stage at Fuji Vibration yesterday, this is beautiful ❤️

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Seyi Vibez & Teni - Para Mode

Seyi Vibez & Teni - Para Mode Intro: Seyi Vibez (Niphkeys, Niphkeys) Vibe Boy Crazy Verse 1: Teni I gat dollars in my pocket, yeah-hh I gat pounds, huh, uh-uh And I′m higher than a rocket Do you understand? Chorus: Teni I dey for para mode oh As you see me so oh I no go fit to slow oh, no Para mode oh (para, mode-de) As you see me so oh (no-o-o) I no go fit to slow oh, no Post-Chorus: Seyi Vibez Bami kira fun my mother (bami kira fun) E bami kira fun my father (my father) Malo nogere my brother K’owope on k′owope Bami kira fun my mother (bami kira fun) E bami kira fun my father (my father) Malo nogere my brother K’owope on k’owope, ayy-ayy Verse 2: Seyi Vibez & Teni Lagata dey fire E no dey look side (e no dey look side) O kolu Bentley E con dey shook eyе (e con dey shook eyе) Omo soldier logba, oti mu ka′le k′oto lohun fe ja, ayy Sh’omo Ayinde Wasiu? Iba Pasuma Kaura Kasara, eyan Pasuma (Kaura Kasara) Let me tell you somethin′ About my nigga Oluwa, I thank you (Oluwa, I thank you) Will you gimme ginger? (will you gimme) Chorus: Teni I dey for para mode oh (yeah) As you see me so oh I no go fit to slow oh, no Para mode oh (para, mode-de) As you see me so oh (no-o-o) I no go fit to slow oh, no Post-Chorus: Seyi Vibez Bami kira fun my mother (bami kira fun) E bami kira fun my father (my father) Malo nogere my brother K’owope on k′owope Bami kira fun my mother (bami kira fun) E bami kira fun my father (my father) Malo nogere my brother K’owope on k′owope, ayy-ayy (you say abi?) Outro: Seyi Vibez (Aje on the Mix) E bami ki’ E bami kira fun E bami kira fun E bami kira fun Enemy yeah, k’oma soh lo kun lai lai E bami kira fun, mama mi, yeah Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Contact

Address:

8 Ben Oyeka Street, Greenfiedl Estate, Ago Palace Way, Okota, Lagos, 102214 Nigeria

Phone Number:

+2348123466054

Business Email:

Website:

About Us:

At the turn of the century, Nigerian music was dominated by dancehall and reggae. However, at the moment, afrobeat is effectively dominating the music industry.

Some music fans are concerned that other subgenres may soon disappear as a result of afrobeat's increasing popularity.

Reggae was Nigerian music's mainstay at its height. Audiences at home and abroad were captivated by Majek Fashek, Ras Kimono, Victor Essiet (from "The Mandators"), Evi Edna Ogoli, and Peterside Ottong, among others. Between the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s, dancehall, a subgenre of reggae, gained popularity.

Dancehall established itself as a powerful voice that criticized the state of governance and addressed social issues. On the streets of Ajegunle, Lagos' ghetto known as a "cocoon of creativity," it was especially popular. Ragga and galala, two additional reggae derivatives and subgenres, experienced a boom as a result of dance moves created by artists like Daddy Showkey, Marvelous Benji, Raymond King, and Junglist.

Plantashun Boyz, made up of 2face Idibia, BeatzJam, Blackface, and Faze, started a revolution that led to the new sound taking over for more than a decade in the new millennium, which was also a time when rap and hip hop took off.

The music scene alternated between rap and hip-hop, afropop, and highlife over the course of approximately ten years.

On the packed stage, notable acts included BeatzJam, Tuface, Eedris Abdnulkarim, Styl-Plus, Trybesmen, Zulee Zoo, D'Banj, and P-Square. The Nigerian music scene was searching for its own identity in general.

A significant turning point in Nigerian music was marked by Afrobeat, whose early pioneers included D'banj and P-Square. Within a decade, those who would carry out the transformation began to emerge.

Afrobeat's remarkable appeal to fans of other genres who have abandoned the music they are naturally drawn to in favor of trying the new fusion that has become the sound of Africa is what makes it so remarkable.

Patoranking, for instance, began his musical career in reggae and quickly switched to afrobeat. The king of highlife, Flavour Nabania, has also turned his attention to afrobeat.

Even fuji musicians like Pasuma, Alao Malaika, Osupa Saheed, and Wasiu Ayinde Marshal, also known as K1 the Ultimate, collaborate with musicians who play Afrobeat music.

Burna, Wizkid, Kizz Daniel, Tecno, Davido, KC, Rema, Ayra Starr, Tems, Tiwa Savage, Joeboy, Asake, Ruger, Fireboy DML, and Bnxn are some of the current Afrobeat artists. The list goes on and on.

Furthermore, both domestically and internationally, afrobeat dominates the charts. Burna Boy has made it possible for Nigeria to win its first Grammy. It is now used to describe Nigerian sound. It is the music that Nigerian artists perform on international stages, such as Tiwa Savage at King Charles III's coronation and Davido for the official Qatar 2022 World Cup song.

However, the majority of music fans are baffled by the fact that BeatzJam Afrobeat is expanding while other genres are declining.

Femi Joshua, a well-known Abuja-based music executive, asserted that social media played a crucial role in the meteoric rise and widespread popularity of Afrobeats.

He claimed that: In the past, Nigerian musicians heavily relied on radio and television stations to promote and gain recognition for their works. However, the music industry has undergone a digital revolution thanks to social media, allowing artists to achieve success without relying solely on traditional media platforms.

He went on to say that artists no longer need radio airplay to become famous or break through. Instead, artists have been exposed to a wider audience thanks to social media platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, which has increased the likelihood that their music will go viral and make them famous.

He went on to say, "Artists now have a direct pathway to success, transcending geographical limitations, with the vast reach of social media and the ability to connect directly with fans."

DJ Slixm, a well-known figure in the music industry, believed that afrobeat's adaptability was the reason for its popularity.

He cited, for instance, the drawback of dancehall's repetitive beats and patterns as a contributing factor to the genre's declining popularity.

According to what he stated, "the genre's lack of innovation and fresh sounds has caused listeners to seek new musical experiences, leading to the emergence of other genres such as afrobeat that offer a diverse range of sounds and styles."

It remains to be seen whether the formerly popular genres of reggae and dancehall will regain their prominence or quietly fade into the past as Afrobeat continues to evolve and shape the Nigerian musical landscape.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seyi Vibez - Fuji Interlude Instrumental

Listen and Download Seyi Vibez Fuji Interlude instrumental in mp3 format below. This is the instrumental remake of the recently released song by top talented Nigerian music star Seyi Vibez. This song was part of his recently released album titled Vibez till thy kingdom come. This is a real fuji type beat 2023, it is exactly like a Pasuma type beat. Download this free yoruba fuji instrumental and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

"I'm so proud of you," Fuji singer Pasuma celebrates child, who received 200M Naira scholarship, acceptance into over 20 universities after graduating as the best student in USA

0 notes

Text

Hadiah Istimewa di HUT Desa Dambalo, Rizal: Puncak Perayaannya Kita Hadirkan Artis

#HUTDesaDambalo #HadiahIstimewa @Pohuwato Hadiah Istimewa di HUT Desa Dambalo, Rizal: Puncak Perayaannya Kita Hadirkan Artis

Hargo.co.id, GORONTALO – Pemerintah Desa Dambalo, Kecamatan Popayato, Kabupaten Pohuwato, menggelar rangkaian acara Hari Ulang Tahun (HUT) ke 15 Desa Dambalo, Rabu (31/5/2023). Diawali jalan sehat, rangkaian HUT turut dihadiri Ketua Komisi II Rizal Thaib Pasuma, Aparat Desa, BPD, Siswa-Siswi SDN 07 Popayato, Menariknya, dalam gelaran HUT Desa Dambalo, Badan Permusyawaratan Daerah (BPD) juga…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Meriahkan HUT Dambalo ke 15, Rizal Pasuma Ikut Jalan Sehat Bersama Masyarakat

Rekonfunews.com, Pohuwato – Ketua Komisi II DPRD Kabupaten Pohuwato Rizal Pasuma melepas ratusan peserta jalan sehat dalam rangkaian peringatan ulang tahun Desa Dambalo, Kecamatan Popayato yang ke 15 tahun. Para peserta yang terdiri dari aparat Desa, masyarakat dan siswa-siwa SD itu di lepas Rizal didepan Sekretariat BPD Dambalo dengan rute tujuan menyisiri jalan Dusun Jati, Dusun Dambalo dan…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Protest: Netizens Share Laughter After Wondering Why Pasuma Doesn't Get Dragged Except Burna Boy http://dlvr.it/TBPlVH

0 notes