#ozlemeli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

come or go, we belong together lying here forever in the cold, cold, cold

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

..

extra:

(it was a spring morning)

(he was a frail boy with no friends)

(he ran into you from across the wall)

(you said hello to him, and asked him to play along)

(at that very moment, he received his lifelong—)

extra 2: oscar boogaloo

yeahhhh....iykyk

#ozpin#professor ozpin#it never gets less embarassing tagging this#rwby#ugh#wait hm#ozma#salem#not tagging ozlem because its kinda giving ottokallen and ergh#oscar pine#sighs anyways#both of them have the same role functionally#they parallel eachother via#hold on im getting ahead of myself#he really does remins me of otto#theyre like prometheus#but with the gift of flight instead of fire#(haha flight as a heavy-handed metaphor for civilization)#they both give said gift through something of the previous civilization#im playing fast and loose w otto but he gave the gift of flight through ingenuity#thus wooden planes#ozpin gave the gift of flight (quite literally) through his magic#thus#gestures vaguely#i have so much more to say but alas ...#horrible corvid anatomy cw#while ozma is kinda su coded tbh...immortal brown dudes dealing with their megalomaniac white-haired situationship core#if you know what im referencing im so so sorry#EVERY NIGHT BRINGS A DREAM BUT THE DAYYYY RELENTLESSLY KEEPS ME AWAKEEEE#honestly idk where the quote is from kevin said it so it must be true

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rwby#jaune arc#professor ozpin#salem#battle mage#grimm knight#at the stake#sword and sorceresses#ozlem

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

rating different ozpins out of 10

There's a lot of them. Long post ahoy.

Volume 1: pale ass man. flings his students into Grimm-infested forests and does not give a FUCK. not actually listening to anyone half the time my autistic king. despite the limited animation, you look into this man's eyes and you can tell he's secretly a little shit (affectionate). 9/10

Volume 2: I was gonna put a screenshot of his face and talk about how much better the lighting is in this volume but I saw this on the wiki and this man has NO ASS. He has NO CAKE. the dilf caring mentor vibes this volume are off the charts yet i can't get over this shot. 4/10 the no ass really hurts him

Volume 3: Colourful lighting, soft gaze, blorbo burdened by the weight of his sins. Not so pale that it hurts to look at. His mischievous demeanour is gone in place of sad immortal old man vibes. A shame to see the silly go, but I love a man with flaws who tries his genuine best to do good. 8/10

Volume 5: This part of the OP was always so jarring to me. The silly has returned but they flattened him and it looks odd. Is he doing the :3 face? 2/10 for hiding it in profile.

Volume 6: The first Ozpin in Maya! Unfortunately, he has to contend with the original Ozma this episode, and sadly his one second of sad old man hours kind of gets outshined by fucking. everything his past incarnations go through. Nice to see him in model again though. 6/10 (Ozma is like. 10/10 btw)

Volume 9: this isn't even ozpin. -100000/10.

Chibi: This is peak. I don't even care anymore. I'll say it. RWBY chibi is the peak of rwby content and I'm tired of pretending it's not. this man is the embodiment of silly. he would :3 and he would have the decency to look at the camera when he does. if this oz ever met salem... okay he'd probably make things a lot worse but it would be really funny. 11/10

Ice Queendom: ∞/10 daddy? sorry. daddy? sorry. daddy? sorry. da

This one render: what are you scheming about you shifty little fucker. this is the face of a man who has done something to mildly inconvenience you and he's waiting for you to realise it. gay ass smirk. i appreciate it for bringing back mischievous ozpin in the maya engine but there is something about this i do not trust. 6/10

(bonus) the exact same render but in this thumbnail with his ex wife: 9.5/10. Salem addition really brings out the best in this one. Ozlem in a romcom. He gets pegged and he's proud of it.

Volume 3 japanese poster: eh. it could be better. I don't sense the silly OR the sad old man OR the fuckable mentor in this one. 1/10.

Volume 6 poster: YEAARGHHH THATS WHAT I CALL ANGST, BABY!!!! 11/10!!!!

Viz manga: with this and ice queendom, the jp side of rwby understands how to make an ozpin that appeals to me, specifically. 20/10.

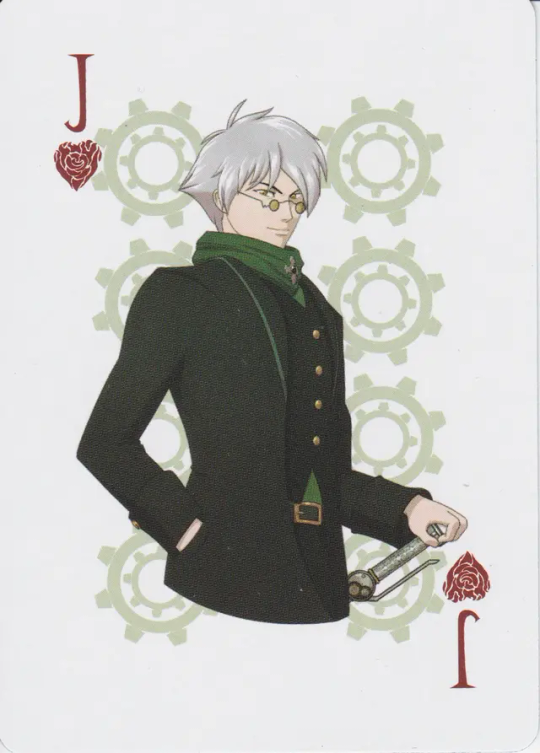

Playing card: the hand in his pocket. the other hand resting lazily on his cane like it's a fucking samurai sword. the slightly cocky smirk. this is Ozpin after spending a day with the Branwen Twins. a young raven and qrow saw this and thought he was the coolest fucking dude ever (he is not). was going to rank it a bit lower but due to my headcanon going straight to ozpin and bird twins I like it. 8/10

this shirt: i would comment more if i could see. 3/10?? he looks sad i think which is nice

DC Comics: PUT THAT FUCKING MOP HAIR BACK!!! -10/10!!! YOU GIVE QROW HIS HAIR GEL BACK RIGHT NOW MISTER

RWBY/JL: this is an imposter. his hair looks like fits on his head like lego figure hair. -2/10

conclusion: i want him to whimper.

#rwby#ozpin#professor ozpin#rwby ice queendom#rwby chibi#ozlem#my post#my thoughts have been plagued by him. he must pay.

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

While everyone's eating in silence someone asks "hypothetically if she wasn't trying to kill us would you fuck salem" alternatively "if your partner got grimified like Salem would you still fuck" chaos ensues

The moment the question came out of Nora's mouth, everyone paused, silent. She only said it in passing, probably expecting no one to hear her.

Ozpin: *Taking Control* I WOULD!

Oscar: I wouldn't!

Ozpin: I'm answering for myself Oscar!

Ruby: I'm with Oscar. I'm not down for it.

Blake: I mean ...

Jaune: I'd be down. I could use a good fuck, and I think she could to. It's probably been a while for her.

Yang: Hold up, Blake, Babe-

Blake: Think of the Kinky Magic stuff we could do!

Ozpin: It's Incredible!

Yang + Oscar: SHUT UP OZ!

Nora: You know, I thought that would get ignored like everything else.

Ren: No.

Blake: I'm just saying, There might be something interesting to try!

Yang: Okay, I mean, it's not like the Grimm part-

Blake: *Guilty look*

Yang: ... Blake, please- I mean if it were You? I'd get it, but too much stuff has happened with Salem-

Ruby: My sister and her Girlfriend are perverts. I'm on a Team of Perverts!

Weiss: I haven't said anything!

Nora: Then answer the question!

Weiss: *Blushing* I don't need to do anything I don't want to!

Ruby: Oh my god my whole team is Filthy!

Jaune: I'd fuck Pyrrha if she was brought back as a Grimm. I've had dreams about it.

Everyone: We Know Jaune.

Ruby: *Stands up, starts walking* I'm done! I'm going! I am Leaving!

Nora: Me and Ren would fuck each other! Waht about you guys and You're partners?

Ren: I would not fuck you if you were a Grimm.

Nora: WHAT!

Ruby: *Turns around, Sits Down* Actually I think I can See it. Might need to be careful with my eyes though.

Weiss: So NOW there's a conversation. Maybe the Rose has been dirtied herself~

Oscar: I am no longer a part of this Conversa- I do not care Oz! I'm not sticking around for this! I'm Heading off!

Ozpin: She gives mad Head.

Oscar: I DIDN'T WANT TO KNOW THAT, OZ!

#rwby#jaune arc#rwby shitpost#ruby rose#yang xiao long#weiss schnee#blake belladonna#nora valkyrie#lie ren#headmaster ozpin#oscar pine#bumbleby#asks and answers#ozlem#anonymous

240 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you elaborate more on if Summer and gylinda (sorry if that's spelled wrong) were narrative foils? That sounds really interesting!

right so from what little we know about what glynda’s been up to since the fall of beacon is that she is, to all appearances, the ONE member of the inner circle who took a deep breath after ozpin died and kept her shit together. the others:

lionheart, already a traitor, continued to ask how high when salem said jump

ironwood exacerbated the global crisis by withdrawing his troops and closing the borders, thus inflicting deep economic pain on mantle and eroding international trust

qrow imploded and had to crawl back up from rock bottom after his faith in ozpin was destroyed

theodore refused to act until it was almost too late to prevent the crown’s coup because he was preoccupied with the more distant threat of salem

but glynda? she took point on the effort to reclaim beacon academy from the grimm and whenever she wasn’t doing that she was personally rebuilding vale. the last we see of her in v3, she’s on the brink of collapse working herself to the bone in vale. but in ‘after the fall’ she’s holding things together, even if just by her fingernails; she’s on top of it enough to have team CFVY’s academic transcripts and a letter of recommendation ready for them when they decide to apply for transfer to shade. in v4, half a year after beacon fell, port and oobleck seem optimistic about the situation at the beacon (“there is still much work to be done at the school” says busy and difficult, but the mood isn’t dire). and when we glimpse her again in v8, it’s apparent that normalcy has been restored in downtown vale; the dust shop is open for business and the streets outside are not overrun by grimm.

glynda had a hellish nightmare situation thrust into her hands as the de facto new headmistress of a fallen school and the person all of vale turned to for protection and guidance in the wake of this horrifying tragedy, and within a year she managed to pick up the pieces and restore peace and safety within the city, even if she couldn’t take back her school. that is astounding, and especially striking in context with the rest of the inner circle crumbling.

what made her different?

this is speculative. but i think that glynda, like summer rose, is a true believer in the ideals that huntsmen are supposed to uphold: compassion, mercy, cooperation, striving for peace, defending those who cannot defend themself. she trusted ozpin, but unlike the others, her loyalty was not for him but for the things he claimed to believe… so when everything fell apart and the burden of leadership landed on her shoulders, she acted in accordance with those ideals. reached out, brought people together, trusted in those who offered their help, and kept widening the circle until the great burden had been shared between many hands. and after salem razes vale? she does the same. goes to find help.

(i don’t think she told anyone about salem, but rather she put her faith in humanity’s capacity to pull together rather than try to shoulder everything herself. this is in contrast to qrow during the haven arc and ironwood, who bring new people into the loop but see the world as hopelessly divided and riven by distrust.)

if i am right about this and also on the mark with regard to summer rose, this would position them as reflections of each other: both huntresses who believe in and embody the true ideal of what they are supposed to be, both guided in their choices by this staunch moral conviction. summer discovers that she is complicit in enacting a horrific injustice and without hesitation turns around to stand with the victim against even her own family; glynda weathers a catastrophic tragedy and stands tall while every other pillar of ozpin’s circle collapses because she puts herself among the people and inspires them to keep pushing with her. both of them Do What’s Right.

which makes it very narratively compelling to juxtapose them with each other, because they are opposites—fighting on opposite sides—but they are also the same.

furthermore, summer has been holding beacon academy against glynda’s siege for the last year-and-a-half or so; either summer has been able to avoid notice during this time, in which case glynda is due to be hit by a freight train of a moment of realization, or glynda has seen her and knows that her opponent is summer rose—a woman who may once have been her student or her classmate, depending how old glynda is supposed to be, and certainly someone she knew and worked with fourteen years ago when they both believed in ozpin.

if that isn’t grounds for a very personal enmity in the vein of cinder and winter or qrow and clover, i will eat. my. hat. summer was there the night beacon fell—she’s the one who left ruby alive when she scraped cinder off the tower—fighting on the side of the grimm. she’s the one who’s been steadily drawing grimm to the school on salem’s behalf! that is glynda’s home! those were her students who died that night! and in reverse, it is almost certainly glynda who knows the secret of the vault’s location, glynda who remains steadfastly loyal to the divine cause of subjugation-or-annihilation, glynda who upholds the system summer fights to tear down. DO YOU SEE MY VISION… the disciplinarian and the revolutionary…

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's funny that I have one story idea where Jaune is Ozma's first body he reincarnates into and then I have another story idea where Jaune is Ozma and Salem's 5th kid and Jaune has ghost sisters who can take physical forms and help him.

Like one is two people struggling to co-exist while dealing with an ancient evil that Salem and Ozma defeated a long time ago who wants to end the world.

While the other one is just a huge Family Fight with emotional drained and tired father, an evil mother who wants to end everything, and 5 kids trying their best while struggling with their own issues.

#rwby#jaune arc#headmaster ozpin#rwby salem#rwby guardian ghost au#rwby choosing sides au#rwby wynona briar#aurora briar#serana briar#odaletta briar#rwby ozlem daughters#rwby ozma

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bir yerde okudum; "Ben sana konuşamadıklarımı hep ağladım" diyordu.

Didem Madak

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyone who thinks Oz and Salem will get back together at the end of the story is legitimately insane

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAIN, KEEP US TOGETHER

#i can still hear you saying you would never break the chain...#rwby#salem#ozma#ozlem#those ancient bitches better get ready. (both speaking in unison) i stand with my cancelled spouse

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Ozlem.

This will be less a singular headcanon than a collection; my reading of the relationship is particular and on several key points, well off the beaten track from popular fanon. I thought it would be helpful to put it all in one place for ease of reference.

Salem’s Childhood.

Salem was the second-born child of a minor lord, born into the eighth generation of mankind since the creation of the world Arziant, in a kingdom called Pastoria. Her mother Salome had been the king’s only child, but not heir to the realm; Pastorian law and custom forbade women to leave their divine appointment within the home. In practice, a woman belonged to her father until she was given to her husband.

In that time, monolatrous worship of the God of Light was nigh-ubiquitous, and tradition held that no one who lived a virtuous life would die before their hundredth year, unless slain in battle or by some violent calamity brought about by the Darkness. To fall ill was proof in itself that one had committed some offense in the eyes of God. This was not mere superstition, for although natural sickness did exist, the God of Light gave healing to those he judged pure and inflicted disease as a punishment for sin.

Death in childbirth, although not (as Salem believes, even now) wholly unknown, was quite rare and supposed to be a punishment reserved only for the truly wicked. Both of Salem’s parents were well-known for their piety, and her father Lord Ithai was scrupulously devout; for his wife to sicken and die in the course of bearing their second child was shocking, not only to Ithai himself but to all of Pastoria. While he would have held the tragedy against her in any circumstance, his personal inclination to do so fed eagerly upon advice from religious advisors who, to preserve Salome’s good name in the eyes of the people, blamed her infant child. There had been, after all, prophecies foretelling the virtue and great deeds of heroes in the past; why not portents of a dire evil?

(In truth, Salome had made an error in a ritual entreating the God of Light to grant his blessings to her unborn child, and he intended to make an example of her carelessness.)

The modern fairytale The Girl in the Tower portrays the girl’s father as a paranoid, possessive tyrant who loves the girl as a miser loves his treasures, who becomes angry and violent when she asks to be set free; this characterization, though not an inaccurate portrait of Lord Ithai himself, elides the misogynistic norms and popular religious justification for Salem’s imprisonment. Simply put, she had no hope of rescue because most of Pastoria truly believed that she was an ill-omened child who needed to be locked away for the good of all.

Salem did not grow up in complete isolation, though she was alone far more often than not: she was raised by an ever-changing parade of servants, priests, and tutors. Her father visited her on occasion; her elder brother Kalev snuck in to see her with greater frequency.

The first twenty-one years of her life, she spent in locked in a single room—little more than a cell, ten paces wide and nine across—at the top of her father’s keep. Her singular window overlooked the block where Ithai executed those whom he suspected of treating her with undue kindness; from the time she was old enough to understand, Salem was made to watch these executions (and in time it became a compulsion to do so, one that still lingers; to this day Salem keeps obsessive count of the deaths she considers to be her fault).

She was nearly always hungry. Of the one hundred forty-three people Ithai executed, in those twenty-one years, most were kitchen servants condemned on suspicion of bringing her too much food, or for lingering to speak with her while she ate; to bring the lord’s daughter a meal, it was well known among the kitchen staff, was to risk one’s life. Quite often, she went without food altogether, and seldom received more than one meal in a day. Salem grew up both hoarding food and feeling intense guilt around eating.

Ithai was, on the rare occasion of his visits, extremely abusive; Salem was so terrified of him that even now she feels on edge around men who remind her of him. (He was quite tall, broad-shouldered, with a full beard; his hair sandy-brown in his youth, half-grey by the time of Salem’s birth; a deep baritone.) She cannot handle being yelled at without shutting down. Her instinctive reaction to violence against herself—to simply take it, quietly, without resistance, and wait for it to be over—is a response she learned in childhood, and unless she is already quite angry, it’s one she finds difficult to overcome.

Escaping the Tower.

In the fairytale, at the age of sixteen, the girl asks her father for paper and pen. She uses these to write pleas for rescue, promising to marry anyone who can save her from her father, and throws them to the wind. Innumerable would-be saviors flock to answer, only to be slain by her father while the girl looks on in horror, until one day a true hero defeats her father in a duel and frees her at last.

This is not quite how it happened.

When Salem was sixteen, and Kalev eighteen, she put to her brother that he should find someone to marry her. She was reaching the proper age (indeed, their mother had been only a year older when the king married her to Ithai), and she could think of no other means to escape than by marriage, though the prospect filled her with dread. Kalev undertook this effort very reluctantly, fearing that anyone willing to marry a girl who’d spent her whole life locked away would undoubtedly be at least as awful as their father; but he did try, without success, for several years.

He was twenty-one, Salem nineteen, when he met Ozma: not an aristocrat but the wandering knight of a holy order who chanced to be nearby when Kalev’s retinue was set upon by the largest wyvern any of them had ever seen. Ozma leapt to Kalev’s aid and slew the grimm, and would have died of the injuries they sustained in doing so had Kalev been less skilled in healing. They talked, afterward, finding they had much in common; and before long, the conversation turned to the plight of Kalev’s sister.

Ozma had no interest in marriage—had sworn vows of chastity, in fact—but Kalev’s account of Salem’s treatment horrified them. They had heard tell of the ill-omened girl held safe within the lord’s keep, of course, but the rumors had given them the impression that she was sickly, too frail to leave her bed. Upon learning the truth, they became determined to help her. Together, the pair hatched a new plan: Ozma would pledge themself as Kalev’s vassal, ingratiate themself to Lord Ithai, and find some opportunity to free Salem in secret.

Two more years would pass before Ozma found their opportunity, for the magic Ithai had woven around her cell would not allow her to cross the threshold, even were the door torn from its hinges. During this time, Ozma stole up the tower whenever they could to visit Salem; they didn’t dare enter the room, for fear of being ensnared by the wards, but they could speak to her through the door.

Without fail, Salem would beg them not to come back; desperate though she was for escape, she did not believe this plan had any chance of working, and lived in terror of Ozma being found out and executed. Ozma, for their part, stayed resolute in their conviction that freeing her was a worthy cause to die for, which had—for as long as they could remember—been the only thing they really wanted.

In the end, what happened is this:

Lord Ithai came to Salem’s cell late one evening, on the same night Ozma risked ascending the tower to talk to her; and though they realized the danger halfway up the stairs, hearing echoes of her father’s tirade, before they turned back as they’d promised her to do if this should ever happen, they heard the unmistakable sound of a blow, a choked cry of pain, and could not find it in themself to leave.

Up they charged. Ithai had his back turned to the door, his hands around Salem’s neck, and Ozma gathered all the magic they knew to strike at him from behind; but Ithai was an experienced combatant. Though wounded, he was not bested, and he whirled around in a murderous fury to retaliate. The duel was swift and brutally decisive—within moments, Ithai shattered Ozma’s defenses and had them on disarmed on the floor.

Salem had collapsed when Ithai dropped her and remained cowering against the wall while the brief battle raged; but when her father raised his hand to strike Ozma dead, with the door open and someone who had been kind to her about to die because of her like so many others, she snapped. Her magic, never trained, and never very strong, exploded outward as she threw herself across the room.

She drove her hand into Ithai’s body as if his flesh were water and ripped his pulverized heart right out of his chest.

That was not what she meant to do, exactly. She had wanted only to make him stop, and twenty-one years of desperate fear crashed together in that moment to become a wild, boundless rage; but no sooner had his body crumpled than reality caught up with her, and then she was only a girl clutching the gory shreds of another person’s insides in her hands, whereupon she became hysterical.

Salem does not, whatsoever, remember leaving the tower, nor anything else until dawn, when she regained her senses to find Ozma coaxing her to let them clean the blood off her hands. But after realizing what had happened, Ozma scrambled up, pried the gore out of her hands, swept a few valuable-looking trinkets into a satchel—they’d wanted her to have something to her name—thrown their cloak around her shoulders, and raced the both of them out of the keep at speed.

The image Jinn presents when Ruby asks her what Ozpin is hiding, of Salem and Ozma fighting their way out together, is a representation of how Ozpin would have told this story: distilled, softened, stripped of personal feeling… but that fight did happen, for the lord’s death and Salem’s passage through his unravelling wards awoke his retinue. Ozma fought; Salem was a storm of uncontrolled violence lashing out in blind panic.

Their First Relationship.

Although Ozma had, over the course of those two years spent whispering through her door, fallen quite hopelessly in love with her, it became clear to them within hours that Salem not feel the same. The satchel of minor valuables they’d hastily gathered for her, she tried to give to them, and their polite refusal to accept caused her to lapse into hollow silence for several minutes before she asked what they wanted from her instead—and only then had they realized how scared she felt that she might be no more to them than a prize.

The first lie Ozma ever told her was that they had never thought of anything but to set right the terrible injustice her father inflicted upon her, and they resolved to take the secret of their infatuation with her to the grave.

Still: she had nowhere else to go, and neither of them dared stay in Pastoria after murdering a nobleman. Ozma offered to take her wherever she liked, and Salem ventured that she had always wanted to see the ocean. In those days, the land formed a single continent, and Pastoria lay nestled at its heart, in the verdant foothills beneath the Light’s sacred mountain.

The long journey would be Ozma’s undoing, for the sea and the edges of the great continent belonged to the God of Darkness, and the vows Ozma had made to Light forbade them to enter Dark’s own country. But they thought nothing of it at the time; their whole life, they had scrupulously abided by the stern, unyielding tenets of their faith while privately yearning for death, only for Salem to ignite within them a ferocious desire to live.

So off they went.

For more than two years, the pair traveled further and further west. Salem grew easier around them, and as her wariness ebbed, true friendship rose to take its place—not the desolate, harrowing need which had bound them both together when they fled, but the simple sense of being kindred spirits. (It was during their travels together that Ozma first decided to worry less over fitting into either manhood or womanhood, and began—just between themself and Salem—to invent an un-gendered mode of address for themself; at the time, the phrase they’re still so fond of repeating in the present, that they are only a man, not even a very good one, was not self-deprecation but a private joke they shared with her at the world’s expense.)

With other people, however, Salem struggled: her speech was stilted and afflicted by a ruinous stutter, she was awkward, she was sometimes volatile and sometimes seemingly void of any emotion at all, she was painfully shy, she could not eat with anyone else looking at her, she sometimes lost the thread of conversations and simply lapsed into silent staring… every invisible scar her childhood left upon her marked her out as strange, as unnatural, perhaps even dangerous.

By the time she and Ozma reached the ocean, Salem felt utterly exhausted and half-certain her brother and Ozma were the only good people in the entire world; she found the desolation of the coast appealed to her, the wild emptiness, the sheer scale of the endless water.

She wanted to stay, and stay they did.

They built a little house upon cliffs overlooking the sea, a day’s walk from the closest village. Planted a garden. Lived. Grimm were far more numerous around the coast than in the heartland, and though the creatures proved to be less trouble than Ozma expected, they still insisted on teaching Salem how to fight, more than the basics she’d picked up along the journey. For a year, all seemed well.

However, though Ozma had long since forgotten their vows, the God of Light did not forgive, and seeing now that his wayward servant had no intention to repent, he at last struck Ozma down.

The sickness killed them slowly; it began with mere fatigue, headaches… mild at first, though they grew ever more severe and lingering until Ozma was left nearly insensate with agony for days at a time. Over the course of nine months, they slid piece by piece into a listless haze of pain and confusion—and though Salem tried everything she could think of to help, even leaving them in village and traveling alone to the nearest city to plead for medical aid or healing from the temple, they died just short of four years after her liberation.

Salem has always, deep down, believed she killed them, somehow.

In all that time, Ozma had never breathed a word to her of how they loved her or the depth of their feeling, still afraid to ask for anything she didn’t want to give; and Salem had only just begun to realize similar feelings for them when they fell ill. The thought that they had died not knowing she loved them was almost as unbearable a torment to her as grief itself.

Salem’s Petitions to the Brothers.

The journey back to the heartland took Salem just seven months. She had pushed herself extraordinarily hard to traverse such a vast distance in so little time, scarcely sleeping or eating and using magic to whip herself onward past the brink of collapse; she was deeply unwell, and her thin hope that the God of Light might take pity was all that kept her standing.

She had always been fervently religious, in her way, although her imprisonment and the abuse she’d suffered and the estrangement she felt from the rest of mankind after her escape had all left her with idiosyncratic, at times nakedly heretical ideas about the Brothers. (For one, Salem had spent most of her life praying to the God of Darkness too, because it never made sense to her that only one of mankind’s creators should be worshipped; she believed, and still believes even today, that it was Darkness who freed her from the paralyzing terror on the night she killed her father.)

Salem had no intention of marching into the sacred domain of the Light to demand anything, nor did she truly expect him to give her what she asked; but she did feel certain there had been some mistake, because good people were not supposed to sicken and die, and she did believe, with all her heart, that the God of Light was just and kind.

When she climbed the marble steps, she imagined that she would kneel before the pool to pray, and perhaps the Light would offer her some sign of comfort, of sorrow, of understanding. For him to appear in front of her himself before she could even utter a word shocked her, and ignited a wild hope that he might actually grant her a miracle—hopes that he shattered by instead chiding her for making demands of him.

That was the first fracture in Salem’s faith. Light sent her out of his realm and left her reeling: he had not been kind. Why reveal himself to her at all, just to rebuke her prayers? It seemed—unfair, even cruel.

Of course she turned to the God of Darkness, then. If even the gods were cruel, Salem did not care to live in the world, and she had worshipped Darkness from afar all her life. Why not seek out kindness from him, or else find merciful death in the jaws of his monsters?

Perhaps, she thought, he was lonely too.

Finding his realm took some doing, for no one in living memory had dared go looking for it; in the end, Salem resorted to following the grimm until one led her to the proper place. By then she had lost all sense of time, exhausted and sick and starving as she was, but it was almost exactly a year since Ozma’s death when she stumbled wearily up the granite steps to visit the God of Darkness.

Though Ozma believes that she asked Darkness to bring them back to life, and lied to him about having gone first to his brother, this is not so. (Salem told them the truth, eons later, as well as she could: but by then she had been so long alone, and the events that had led to mankind’s destruction were so distant, that her account had been meandering and confused, difficult to follow. The answer Jinn gives Ruby is not absolute truth, only exactly what Ozpin believed to be true and chose to hide, and contains a great deal of guesswork on Ozma’s part, to make sense of it all.)

What she did do is tell Darkness of all her sorrow, vowing to revere him above his brother for the rest of her life if he ended her pain. Salem half-hoped he would unite her with Ozma in death—it seemed a fitting mercy, from the god of destruction—and half-feared he would answer by unburdening her of the capacity to feel at all. Until he did so, it never occurred to her to imagine that Darkness would grant her the favor his brother had coldly forbidden her to even want.

But he did, and during that brief moment before the God of Light appeared in all his icy wrath, Salem had every intention to uphold her end of the bargain. Light had treated her with cold disdain, but in Darkness she had found the kindness she had been taught to expect from his supposedly benevolent brother; she would never again worship the God of Light, and had Light not interfered then, she would have become a devoted, unendingly faithful disciple to the God of Darkness.

Instead, the Brothers twice incinerated Ozma in her arms and drowned her in the fountain of life to consign her to a deathless eternity alone, and that was the second fracture in her faith.

Her Rebellion.

When the Brothers cast her out of Light’s realm, they sent her home: to the cliffside by the sea where she and Ozma had lived.

The very first thing Salem did was hurl herself into the sea.

How long she spent drowning and drowning and unable to die beneath the waves, Salem did not know; by the time a (distraught) fisherman discovered her undying but horrifically broken body in his net, the little house on the cliff had fallen into ruin, and the village she remembered had grown into a large and prosperous town.

The fountain of life had poured into her soul—which left the physical pool in the Light’s domain a mere puddle of water with no magical properties at all—and remade her into the very wellspring of creation itself; the life-force humans would, much later, come to know as aura. No matter the severity of her injuries, she could not die, but healing serious injuries with aura requires training, focus.

Salem had healed imperfectly: the bones she had shattered when she plunged into the sea knitting back together at strange angles, her body bent and distorted by the uncontrolled and unchecked growth of masses that would have killed anyone mortal, her chest distended with seawater. She could barely move, let alone speak, and it was only good fortune that the fisherman who had found her overcame his panic before casting her overboard again.

He brought her to Light’s temple, in the town that had once been a village. The priests there were baffled, but they could see that she was in terrible pain, and they did what they could to help her. Mostly, this was miserable: a matter of breaking bones and carving out tumors, little by little pulling her body back into human shape.

She did not make it easy for them. The ruin of her physical body had not diminished her magical power, and as soon as Salem understood where she was she began to lash out, wanting nothing to do with the gods who had done this to her. Still, the priests felt sorry for her—and assumed that her violent reactions were motivated by pain, rather than hatred of the god they served—so they persisted.

Then the ones who had taken charge of her care began to sicken, and Salem realized two things: first, that they were not caring for her under Light’s auspices; and second, that he accounted the kindness they were trying to give her a sin deserving of punishment.

That was the third, and final, fracture in her faith. She stopped fighting her caretakers and bent every effort toward healing herself and trying to heal them; in this, she failed, and watched those who had aided her die one by one even as she was restored to perfect health.

She was outraged.

Yes, she had prayed for things she was not meant to have, and yes, she had sown discord between the Brothers by mistake, and yes, she had railed against them and called them monsters when they ripped her love away from her again. Perhaps that did make her selfish, arrogant, deserving of the torment they inflicted upon her—but these people had done nothing to deserve death.

It was an injustice.

It was worse than cruel; it was wrong.

Salem returned to Pastoria brimming with righteous fury. There, to her surprise, she found Kalev—an old man now, though she still looked not a day older than twenty-five.

The reunion was strange and bittersweet. Kalev had spent most of his life wondering what happened to her, praying to God to keep her safe and happy, and to learn that the Brothers had treated her with such brutality devastated him. From his devastation and her rage, the first spark of rebellion was struck.

When Salem set out to galvanize others to their cause, she told the truth: of the injustices and cruelty she had seen; of how the Brothers had made her immortal by throwing her into the fountain of life, and so revoked the promise of healing for the pure from the rest of the world; of the division she had seen between Light and Darkness; of her vision of a new world freed from the chains of their creators. The gory spectacle of her immortality and the fervent truth of her convictions overcame every obstacle that had always set her apart from the rest of her kind.

Though it was Salem who lit the match, the firestorm she unleashed surpassed her expectations, and when the rebellion stormed the marble steps to Light’s domain, the movement had long since grown beyond her, grown bigger than the faint hope she clung to that she might find a way to die after the Brothers were gone.

(She wouldn’t recognize it until eons later, but she had already begun, even then, to resign herself to the possibility of living forever.)

The Moonfall and the Making of Remnant.

See this post.

Upon climbing back out of the pool of grimm, Salem found that it, just as the fountain of life had done, had poured itself into her soul. The vast and infinite well over which Darkness once presided had diminished to mere scattered ponds of atrum, still capable of birthing grimm if given a spark of life yet no longer alive as the dark lake had been; and she felt that vast and infinite power churning within herself now, mixing together with the molten radiance of the fountain. She began to have an inkling, then, of what she had done.

Eons ago, the Brothers created mankind by the admixture of their two natures—so went the old stories—creation and destruction bound together in one. Salem had thought to do the same, when she bore the light into the pool, but instead… some intangible barrier had shattered, she thought, had fallen into dust and less than dust. The waters mingled: and here is fire.

She wandered away from the Dark’s onetime domain in a daze, unsure of what she would find in this new world but excited to meet it, and what she found was the first and second of Remnant’s peoples: the fauni, who were no more human than she, and the grimm, as fierce and wild as she remembered.

Humans would come later. Salem has… complicated feelings about mankind, these days, a mixture of admiration for their virtues—their strength, their wisdom, their resourcefulness, their passion, their ingenuity, their hope—and profound wariness. She has not thought of herself as human since that half-century beneath the waves, and even less since her transformation in the dark lake; she is grimm, she is the one called God of Animals, the fauni are her people, and she does not much care for the way humans treat those who are different from themselves.

The First Reunion.

Ozma knew nothing of this, when the God of Light sent them back into life. They knew only what Light told them: that Darkness had destroyed mankind for an offense he implied had something to do with Salem, that humanity would rise anew in desperate need of redemption lest they be condemned to obliteration, and that though Salem yet lived, she was no longer the woman they held dear.

When they agreed to return, Ozma did not give a damn about any of this. Salem lived. No matter how she’d changed, they felt certain beyond any doubt that they would love her still, and when the words I’ll do it left their mouth, they had every intention of finding her at once.

But nothing could have prepared them to wrench awake behind a stranger’s eyes, nor for the overwhelming flood of another’s mind shattering and bleeding into their own. Nothing could have prepared them to feel the like-minded soul die so that they could live.

Nothing prepared them for the horrors of this new world, where humans bereft of magic cowered in the shadows like rats among grimm who now seemed all but unstoppable. Nor could they fathom the scale of suffering they saw everywhere they went: the senseless ravages of disease, the brutal and desperate wars over resources that had once been abundant, the seemingly endless panoply of false gods and false creeds which served as pretext for yet more war, the almost-human creatures called faunus who—they were told—lived bestial lives in the wilderness, whom the grimm did not hunt because they had no souls, who hated humanity just as fiercely as did the grimm… who served and worshipped the malignant Witch of the Wastes.

She had to be Salem. Ozma knew it from the moment they heard the first whisper of that name, for who else in this damned and desolate world could wield power of that kind?

Fear crept over them. Doubt. They remembered what she had done to her father, the spectacular violence in her fear; Ozma had never been blind to Salem’s wrath. What had happened to her, after they died? What had she done? What if—in the end it was this thought that overcame the rest of Ozma’s worries and brought them to her doorstep, heart in their mouth—what if the God of Darkness had laid a curse upon her?

(Might she still be saved, even now?)

Some of those fears melted away when Salem opened her door and Ozma looked into her eyes at long last: they knew at once that she was still herself, and for a while that was all that mattered.

For her part, Salem had long since made peace with never seeing Ozma again; she held on to a faint hope that their soul might be reborn, now that the gates of death had cracked, but she knew—thought she knew—that they would never return as themself, and she might never find their soul again. Her grief had become a deep ache, never quite fading but possible to live with, around, through. What else was there for her to do but keep living?

(Sometimes—now and then, when the anguish rose to the surface again—her mind did conjure echoes of them. She had spent countless nights of her interminable isolation huddling miserably in their arms, half-dreaming and half-believing they were really there. It comforted her sometimes to pretend not to know these were only hallucinations; she liked to imagine their spirit lingering with her, reaching out to soothe her when she could bear the pain no longer. But even that had not happened in a very long time, when Ozma found her.)

The first thought to arise from the searing, wordless shock of finding them before her once again was wonder at the recognition aglow in their eyes, the smile dawning upon their face as if no time had passed at all; the second, an overwhelming terror that this wasn’t real.

Both were cautious, in the beginning. Salem felt acutely aware of how much she had changed, how foolish it would be to expect everything to go back to the way it was in that little house by the sea; Ozma’s fear that she had been cursed by Darkness seemed all but confirmed by her grimm appearance and the bizarre, erratic tale she told of defying the Brothers and plunging into the divine wellsprings. She could do magic no longer, for the Brothers had torn their gifts from her soul, and the wild power she held now was unlike anything Ozma had seen.

Yet… even so.

Every troubling tale they’d heard of the Witch proved to have a reasonable explanation. Of course the fauni had souls (and Ozma has never quite lost their mortification for believing otherwise), and Salem’s careful observations of the grimm led her to believe they were drawn to powerful negative emotion: hatred, anger, misery, envy, fear, all feelings roused by the rampant persecution of faunuskind at human hands. She offered protection to those fauni who sought her out, and sometimes stole into settlements late at night to set captive fauni free. In the village nestled along the edge of her woods, she was well-regarded—if still a little feared, for she seldom left the woods unless someone came to ask for her help.

Those first few weeks together in her cottage were peculiar, thick with dread and uncertainty and the awkward feeling of the eons now lying between them; there had been missteps and hurtful misunderstandings aplenty, while they learnt each other again.

She was different: she had acquired a sardonic sense of humor which delighted them, an astounding depth of knowledge on the natural forces of the world, an alarming farrago of new gods, a vicious temper that often saw her storming out of their cottage to (she admitted to them once, rather sheepishly, when they asked) lurk at the bottom of a lake for hours to calm herself…

But though they looked, Ozma could find nothing in her to fear; she was still kind, still inquisitive, still terribly shy, still—true enough that Salem was no longer the awkward, volatile, passionate girl they’d held so dear, but that girl wasn’t gone. She had only grown into herself, and each day they loved her more.

Ozma didn’t exactly intend to lie to her.

For those first few weeks, they kept what the God of Light had told them to themself, wanting to hear Salem’s side of the story before they made any judgments; and as weeks turned to months, Ozma concluded that, cursed by the Brothers though she was, nothing was wrong with Salem, and they resolved to forget their task as they had once forgotten their vows to be with her.

They found that they could not. Even as the love they shared with Salem, never quite fully realized in their previous life, put down roots and blossomed in this one, the suffering they had seen—the promise of obliteration—the twisted, still-bleeding shrapnel of the boy they had overtaken—all of it still lurked in the back of their mind, impossible to forget and growing ever harder to ignore.

In the present, when Ruby asked Jinn her question, Ozpin did almost believe that Salem had lied to Ozma, used them, led them blind and infatuated to their ruin: but that is only the lie Ozma has clung to for centuries.

The truth, far more painful, is that Salem trusted them. In spite of everything she had suffered, despite her terror of rejection, of losing them again; despite the fact that they answered her eager questions about how they’d found their way back with naught but vague nothings, Salem chose to give them her trust and her love and her unwavering faith; and so, when they cautiously ventured to lament the division they saw tearing Remnant apart, she had looked at them with hope shining in her eyes and promised to help them heal the world of its wounds.

To create a paradise—without the Brothers.

Ozma should have told her then. In that moment, they had known she would never break from her hatred of the gods who had slain the last world and tortured her for so long, would never submit to them again, and that had been the right time to tell her.

But they’d looked into her eyes, and imagined that boundless admiration curdling in betrayal and disgust, and instead they had leaned closer to kiss her and said, let’s do it.

Lux Aeterna.

Every lie that followed came easier than the last. Salem balked at too grand ambitions, and it often seemed to Ozma that she would have preferred to stay in that cottage with them forever—it was plain to see she did not much like standing before crowds, let alone leading a country, for all that she could be a dazzling orator when she had time to prepare—but they found they could persuade her to agree to almost any course of action so long as they gave it to her piecemeal.

(There were some lines she would not cross: Salem flatly refused to even consider imposing prison sentences, no matter the crime, and she afforded no patience to those humans who protested bitterly at being treated as equals to faunuskind under Aeternian law. But Ozma considered that she was often on the right side of these lines, and did not trouble themself much over her stubbornness.)

The girls were a surprise bordering on miraculous. Salem and Ozma had talked about wanting to have children, raise a family, but neither believed Salem could bear her own. (Ozma could not help but see it as a good omen, a sign that they were on the right path, and all the more so each time their daughters came out human.) Mara, the eldest; the twins, Dana and Lital; and Esther, the baby.

For a time, all seemed well. Lux Aeterna soared to prominence in the region: a small but prosperous city-state ruled by fair-minded, if frightfully powerful, rulers, a place where all were welcome regardless of appearance or culture or creed.

The troubles started small.

Ozma, plagued by terrible nightmares of the final judgment and knowing that this harmonious medley of differences was not what the God of Light truly meant by unity, grew ever more nervous about their utter failure to nudge Salem toward adopting a unified state religion.

Many of their people did worship Salem and Ozma, of course, just as planned. However…

Salem had been the one who put forward the idea of claiming divinity, but it quickly became apparent that Salem meant something quite different than what Ozma had thought: they’d envisioned a stepping stone toward acting as heralds for the true God, condemning the worship of false idols. But to her, becoming gods meant little more than fulfilling a certain societal role, one which overcame every difficulty she found in connecting with other people by simply asking them to accept her as an inhuman being who acted in accordance with inhuman rules. She cared not at all for the trappings nor the power of godhood; she just liked the rules, the contractual nature of relationships built on ritual and reciprocal favors.

Thus the worship of other gods did not trouble her whatsoever; Ozma could not even persuade her to stop adopting more of the gods invented by Remnant’s people, let alone to condemn the worship of false idols. Nor could they explain why it troubled them so without revealing their deception, and so they fretted, and their occasional arguments on the subject never came to any satisfying conclusions.

Then came the intractable problem of what Salem looked like, and the stories told about her across the region.

Grimm did not trouble Lux Aeterna, but they did prey upon her neighbors—many of them ancient human city-states wherein fauni were still enslaved and viewed with deep suspicion; many of them envious and resentful of the way Lux Aeterna flourished. Rumors began to spread of dark rituals performed by the Grimm Queen in the wilderness at night; baseless accusations of human sacrifice, of secret cannibalism, of Aeternians driving grimm into other kingdoms in order to steal more land, and similar fare.

Ozma tried desperately to lower tensions through diplomatic appeasement, ignoring Salem’s blunt insistence that it wouldn’t work. (She had seen this play out many times, in many places, and her cynicism with regard to mankind’s fear of the unknown is boundless.)

It did not work.

Rumors became threats, threats turned to actual incursions against Lux Aeterna’s borders—and one gory assassination attempt against Salem herself, which shook Ozma very badly—and when a vigorous, decisive defense of the borders failed to put an end to all the saber-rattling, Lux Aeterna took the offensive.

With the onset of war, Ozma discovered a new side of Salem that they had never yet seen: she had a strategic brilliance that spoke to deep experience, and she was utterly, dispassionately ruthless. In swift succession, one after the next, each hostile city-state crumbled and bent the knee beneath the Aeternian banner.

Salem approached this conquest with an attitude of grim necessity: there could be no peace with these wolves snarling at the door, and so the wolves must be broken and brought to heel. To Ozma, the merciless expansion of their borders felt by turns intoxicating—for how simple it was after all, to bring people together by the sword—and horrifying.

The Shattering.

One of the many things Ozma reflected upon, during their protracted withdrawal after Jinn caused them to relive all this, is whether Salem had begun to suspect the truth, near the end. Throughout the last few of the thirteen years they shared, she developed a habit of making disquietingly blunt remarks about what they were doing; about the necessity of conquest, if Ozma truly wished to unite the world behind their banner.

Salem did not have any idea what Ozma was hiding from her, but she did know that there was something they would not tell her; and as the war raged on, she grew ever more impatient with Ozma’s—as she saw it—willful blindness to the cost of their grand ambition. To bring freedom and peace to a small portion of the world, that could be done with ease: one needed only to give people something true, a common cause to strive for, and then shepherd it from one generation to the next. Lasting change did not dawn quickly.

(They were still, she often reminded herself, so young. She had been impatient once, too.)

Lux Aeterna had always seemed to her far more precarious than Ozma believed, an idealistic, fragile experiment surrounded on all sides by adversaries who would like nothing better than to tear it to shreds; years before the possibility of war even crossed Ozma’s mind, Salem had deemed it inevitable and made quiet preparations to insure that the outcome fell in their favor. (Her web of spies was vast, intricate, and wholly invisible to Ozma.)

One thing to prepare for war; another to wage it and hear her partner speak dreamily of bringing the whole world together and in the same breath recoil from the bloodshed.

It vexed her that they couldn’t seem to grasp that one implied the other. More than that, it crushed her to think that they were not satisfied with the life they had built with her, even more than it hurt when she realized they wanted more than a simple life together in her cottage. Salem had grown to like Lux Aeterna, despite her misgivings. She cared for its people; she loved her own daughters to bits; she loved Ozma. She was not… exactly… unhappy.

But she was not exactly happy, either. She felt inadequate, and taken for granted, and with ever-growing frequency in those last few years, like everything she did was wrong somehow. Whatever Ozma refused to tell her was plainly tearing them apart, and they seemed to always be further out of reach.

By the end, Salem had begun to question whether they even loved her anymore, or if all that really bound them together was inertia, or tired habit, or some misguided sense of obligation to her and their daughters.

The truth was worse, and far more horrible than Salem could ever have guessed: that the Brothers she’d thought long gone were trying to claw their way back was awful enough, that they wanted to butcher this world too a nightmare almost beyond comprehension, but the depth of Ozma’s betrayal in serving those monsters for all this time, in manipulating her into enacting their design, was beyond her ability to fathom. She could not understand it. (She still cannot understand it.)

There is a very old story faunuskind used to tell about where they came from, called The Shallow Sea: in it, the God of Animals gathers all the unhappy misfits and outcasts of the world and brings them to a certain island—a harsh new world where they can make their own home, if they choose. All they need to do is leap into the magical waters of the sea and swim ashore, shedding their old human skins to become something new.

Most choose to embrace the change, the chance for freedom given to them; but a small handful refuse, spitting accusations at the god and their chosen people, so the god sends them back home to their old lives, and for the rest of time, the ones who refused to change and all their descendants hate and fear the fauni, for reminding them of what they are not and never can be.

This is the myth Salem quoted to Ozma when she refused to go along with the divine plan for Remnant’s future, and this is what she meant: that the Brothers are of a kind with the resentful humans in the story, seething impotently that the world has outgrown them, and they deserve nothing but scorn; that humanity cannot be saved because there is nothing to redeem, and the only course is to press onward; that the world will never again be what it was.

Both she and Ozma understood her meaning perfectly. (No one else who witnessed Jinn’s answer did, a fact Ozma has not actually realized yet. When they tell Hazel that Salem is cursed to live for as long as the world turns and that she craves only death, they are—as they so often do—lying through their teeth.)

Salem does not remember anymore what she said, exactly, for she’s torn and twisted the memory so badly in desperation to make sense of it that the only thing she remembers is the emotion, and the way Ozma glared at her before they stormed out of the study.

Nearly four hours elapsed between that moment and Salem catching Ozma leaving with the girls. Most of that time, Ozma spent at war with themself, torn between their desperation to stay with Salem and their terror of what punishment the Light would inflict upon her, upon their daughters, upon the whole world if Ozma defied him. Salem, meanwhile, was sitting where Ozma had left her in a state of abject shock and horror.

Both were so on edge by the time they came face-to-face in the corridor that they broke at almost exactly the same time, and both remember seeing the other move to attack first. (In The Lost Fable, there is a very brief shot in which Ozma tightens their grip on their staff—bracing themself—and then Salem visibly startles at that movement the instant before she snaps.) Both were caught up in an overwhelming tide of desperate fury and years of pent-up resentment and distrust that had long since eroded the foundation of their relationship, and both were one hundred percent focused on trying to kill the other.

Neither of them knows exactly what happened to their daughters.

& The Rest.

Since that night, Salem and Ozma have seen each other only twice—in the apocalyptic final battle for Ruakh, and in Atlas when she captured Oscar.

Salem has largely done her best to avoid them, not caring what they did so long as she knew they didn’t have all four relics. She never wanted to see them again, after Ruakh. Ozma, meanwhile, has never stopped hating themself for sacrificing her for the sake of the divine plan… but the divine plan is all they have left, and they do not believe she could ever forgive them, so they keep stumbling through the motions of trying. Their paranoia, their tendency to see her in the shadows of every conflict and every grimm, arises from a mixture of intense guilt and twisted longing.

Salem is not aware that they do not have a choice about coming back, and nearly all her hatred in the present is founded upon her belief that they have spent the last three or four thousand years making a deliberate choice to murder an innocent person each time they return, either out of sheer zealotry or an obsessive desire to punish her. The instant she learns this is not so, her rage will rebound tenfold on the God of Light.

The girls did not, in fact, die that night. Ozma’s semblance—once they’re free, once it manifests in its fully-realized form—will reach back four thousand years to the moment the fight began and simply bring them forward. Or it has already done so, depending upon one’s perspective, and they just haven’t arrived at the right moment yet. Either way, to the children it is as if no time passes at all.

(The girls disappear from the scene right before the fight begins, and V9 gave me time travel shenanigans. I am in constant misery. Let me have this.)

#MAIDENS AND KINGDOMS ( hc. )#THIS DARK THING THAT SLEEPS IN ME ( hc: salem. )#FOND HEARTS CHARRED AS ANY MATCH ( hc: ozma. )#parental abuse cw#[ in conclusion: ozlem. (anguished screaming) ]

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

FINAL BRACKET - ROUND TWO: HELLBIRDS VS OZLEM

Propaganda is below the cut.

HELLBIRDS

"canonical choking out, whats not to love. that moment where they swap weapons midfight tho, I am looking disrespectfully."

OZLEM

"Ozlem is literally a disney fairytale romance, there's a girl saved from a tower and an evil father, there's defying the gods to get the one you love back, there's a kingdom and a castle and four kids. They are literal soulmates for eternity, she still calls him 'my ozma' its all there."

#rwby#problematic rwby shipping poll#raven branwen#cinder fall#hellbirds#salem#ozma#ozlem#final bracket#final bracket round two

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ATEŞLEER DANS EDER GECENİN KOLLARINDA AYIRMAK YÜREK İSTER SARIL BANAA🎙🎶⚡️

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually if somebody broke me out right now and/or fixed my door I WOULD be so ride or die that I'd go to the ends of the literal earth to draw out the hidden flaws of my cruel gods. Thanks very much

6 notes

·

View notes