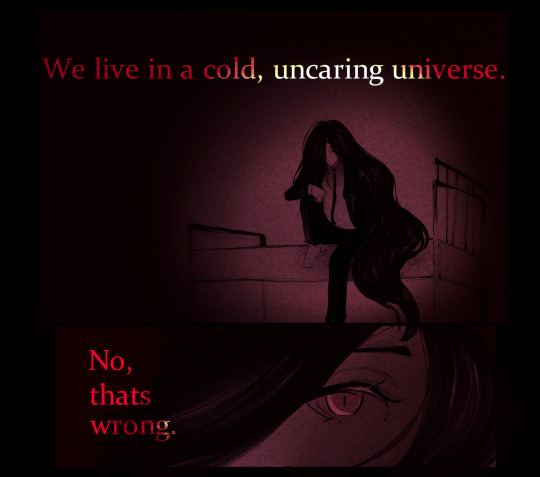

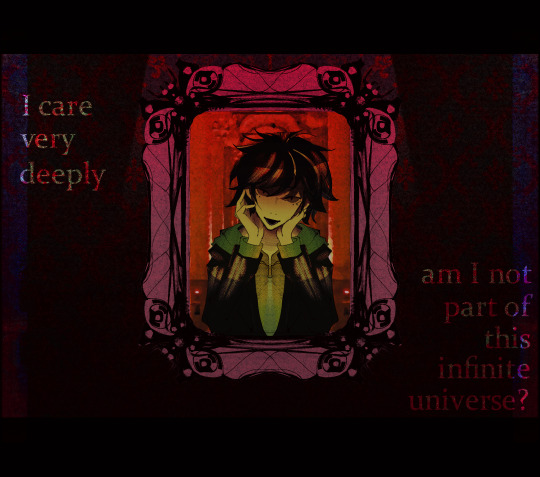

#originally intended this to be charcoal and oil pastel piece on canvas but then i realized i have limited supplies and money

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

बारा.

Nihilism and Absurdism

one/?

#originally intended this to be charcoal and oil pastel piece on canvas but then i realized i have limited supplies and money#starting a short comic with these two. and note to self please stick with black and white from now on please#kannon stop drawing men with mascara challenge difficulty level: impossible#please do zoom in. the textures here are delicious#art#illustration#krita#artists of tumblr#artists on tumblr#danganronpa#anime#makoto naegi#hajime hinata#izuru kamukura#fucked up typography somewhere out there a design student is dying

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Evaluation of the Cinematographer Unit

The aim of the brief was to decipher the importance of form and composition within the art of cinematography and the connection between cinematography and graphic arts. The way in which I explored cinematography was via investigating the concept that singular frames/images from a still can work as a standalone piece. The art of cinematography being the ability to have this effect run continuously throughout the film. My aim was to show that the stills didn’t require colour, special effects or complicated camera shots to still be able a effective. We then took to a list of pre-selected films celebrated for there use of cinematography, after analysing all of the film’s trailers we were then set the task of selecting three films to do further in depth analysis on I chose 3 from varying time periods ���Moonlight (2016)”, “The terminator (1984) and “Night of the Hunter (1955)”, finally we had to make a decision on what one film we would take further to complete final frames on, mine being “Night of the Hunter”.

During this unit we were tasked to do our own research on Artists and designers that we could relate to and infuse our own work with David especially noted to look at the works of “Edward Hopper”. Most of Hopper’s best work was during 1940’s wartime America which was mainly set during this period, depicting unknown figures in an urban environment e.g. “Nighthawks”, “Office in a small city”, “Early Sunday Morning and Night shadows. The processes used to create these pieces were very varied from etching, ink, water colours and charcoal. I proceeded to do a large amount of experimentation mainly with inks, a few Etchings, carbon transfers and a charcoal hand render.

Here are a few example comparisons.

Hopper’s piece titled “Study for Morning in a City” using Charcoal.

My hand render of a scene from “Night of the hunter” using charcoal and black oil pastel.

Something I tried to take away from many of hopper’s studies in charcoal was to try and use more suggestive marks and shapes when hand rendering.

Hopper’s scenic watercolour titled “Slopes on the Grand Teton”

My Indian ink scenic painting of another still from the “Night of the Hunter”

I took away from hopper’s work this time that the same brush can be used many different ways allowing you to create different textures/marks making it easier to put your point across.

During this unit we were asked to explore a range of processes to convey visual language, personally I believe this was achieved by using multiple mediums to create works and experimentation/study pieces. For example my final six frames consisted of two acetate enlargement ink paintings, one “expose and replace” combined with Ink hand rendering, one mono print portrait, one oil pastel and carbon render and finally a solely digital rendition of a scene. All frames had a clean up digitally whilst some of the renditions had a complete transformation. The amount of experimentation doesn’t end there, many of the practical workshops/studies that were created consisted of pencil/biro hand renders, etching and printing in many different formats. This has given me a greater insight on how visual language is composed of more than colour and shape but a big factor can be texture, as discovered whilst experimenting with mono prints and etching prints.

Processes/Material that I found to be very effective at communicating visual language with minimal effort/difficulty are as follows:

Standard Indian Ink painting Due to my increasing confidence with hand rendering with brushes I believe it was easier for me to communicate to a audience what I was trying to portray

Mono-printing The texture that was created with the oil based ink was something that I felt was really effective at communicating visual language

Digital renditions Because of my prior confidence in use of Photoshop and learning of Illustrator I believe that I personally had the tools required to recreate the stills and manipulate the message to what was intended

My increasing confidence in hand rendering lead me to continue spending more and more time experimenting with Indian ink, this was a positive and negative decision/outcome of the confidence boost because whilst I was “wasting” (using the term loosely here) time experimenting excessively with ink, I managed to create a fairly extensive texture pack that i could then use further in not only this unit but future ones as well.

Processes/Materials that I found to be very difficult to convey visual language were as follows:

Oil Pastel & Charcoal renditions As stated previously my confidence in hand renditions is improving with brushes, due to my lack of experience with the use of this material/process I found it very difficult to convey the point that I was trying to make with my work, this hopefully should improve with experience

Pencil & Pen renditions Without repeating myself too much, my low but growing confidence in hand drawing is increasing whether it being pencil, pen, charcoal or pastel (Practice makes perfect)

Personally I believe I have a gap in knowledge of techniques on how to use the equipment above e.g. shading with pencils,different pencil hardness etc. This is something that I will be working towards addressing in the following units to come.

Above is the display of my six final outcomes. (Left to right top to bottom)

Mono-print Portrait I selected this methodology to create this image because the nature of the scene and the angle gave me a large amount of room to maneuver with shadows and tonal value. The reasoning behind using black ink rather than coloured was to maintain the ambiguity of the scene, using cartridge paper created a sand paper like feel to the surface which reinforced the rough and suspenseful atmosphere the scene had created. The main limitation of using mono printing was that a large amount of detail gets lost in the process, adding to the difficulties was the process has many pitfalls that you have to be cautious of for example when removing the cartridge paper you have to be very careful not to smudge/smear any ink that has just been applied to the surface.

Expose and Replace The combined methodology behind this still was to cut out a small section form a printout of the scene, layering that on top of a blank canvas to hand render the background, finally scan the outcome to manipulate the image via adding a Vignette, Gaussian blur and finally a colour overlay multiplying a deep blood red into the sky in the scene. I used this combination of methodologies because as I was recreating the image I believed rather than just bringing the same meaning to the scene that was already in place I would be beneficial to imply another meaning to the frame.

Digital Recreation When selecting this scene to be apart of my final selection I decided to keep it simple to show a contrast from the complicated hand rendered pieces. Keeping with the theme of the film and still I wanted to communicate the very sinister and dark tone that the main character, Reverend Harry Powell, possesses. My goal was achieved via reducing the light in the scene by playing with the tone levels, then multiplying a simple colour overlay of a dark vermilion, finally utilising my texture pack to give the still a dirty, grainy texture amplifying the characters cloudy/muddy personality. A limitation that this methodology has due to my intermediary skill level I believe I couldn’t transform the still as much as I would of hoped to.

“Big Blue” (Blue Ink Enlargement) Deviating from my three previous sinister recreations I decided I wanted to try and portray the character in a different light rather than just a cold blooded killer, reflecting the battle between “good” and “evil” that the character “advocates”. To do so I decided to print the frame on acetate then to enlarge it on a projector, using no previous markings I tried to create a more natural suggestive Ink painting in a similar style to how Edward hopper used water colours. This being my favourite out of all of the final recreations, due to the reasonable difficulty level.

Ink and Digital Scenic Re-Colour Enlargement Another deviation with a enlargement of a panning shot, I recreated the scene the same way as “Big Blue” instead of using coloured ink I created a vary of shades of black to then multiply multiple colour overlays and saturation tweaks to create a more peaceful scene. I believe I achieved this well with the use of suggestive brush strokes and light pastel colours. The limitations to this methodology is that using very suggestive marks results in a loss of detail as I learned.

Oil paste, Charcoal and Digital rendition In this frame I decided to amplify the Distress/tension in the scene I believe this was achieved with the aggressive use of of pastels to shade and fill the scene. This methodology was not very difficult but I am not happy with the outcome due to the inaccuracies of my depiction of the Reverend Harry Powell. I attempted to link this to hoppers charcoal studies that he would use in his works, whether or not it worked. Limitations of this was the detailing of the characters could not be maintained so in a attempt to correct this I resulted in abstracting them more.

In my opinion I believe that my original intentions were met “to show that the stills didn’t require colour, special effects or complicated camera shots to still be able a effective“. Because my final pieces that I have created work well as standalone images and the stills that I chose to recreate dint have any special effects or even colour.

Points of improvement for the next unit:

Time keeping

Ask questions on terminology that I am not confident with

Drawing technique

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: John D. Graham and “Another Way of Making Modern Art”

John D. Graham, “Two Sisters” (1944), oil, enamel, pencil, charcoal, and casein on composition board, 47 7/8 x 48 inches, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Alexander M. BIng fund (all photographs by the author for Hyperallergic)

WATER MILL, New York — Last August, I wrote a piece about “Kali Yuga” (c.1952), a painting in oil, casein, chalk, ballpoint pen, and graphite pencil on cardboard by John D. Graham. It was hanging at the Whitney Museum of American Art as part of the yearlong exhibition, Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection, in a section called “Cracked Mirror,” which featured portraiture from the years before, during and immediately after World War II.

But I had not intended to write about that painting. I was initially struck by a very strange Magic Realist work in oil on wood from 1950 by John Wilde, an artist I didn’t know. Titled “Work Reconsidered #1,” it was a portrait of the artist’s wife Helen, in which she sits sideways to the viewer, nude, her elbow resting on a starched tablecloth and her index finger pointing straight up at a floating, creased sheet of paper with “OBJECTA e. dv.” calligraphed in Roman script. Her eyes, in three-quarter profile, directly address the viewer. Her enormous mass of hair is adorned with strings of pearls, and butterflies have alighted on her skin.

At first the curious imagery, coupled with the potential for a fresh discovery, held my attention, but after a while its labored technique and throwback motifs began to wear thin, and I found myself increasingly glancing to my right, where, on the other side of a realist rendering of a skeleton (“The Shadow,” 1950, by Stephen Greene), “Kali Yuga” hung.

John D. Graham, “Kali Yuga” (c.1952), oil, casein, chalk, ballpoint pen, and graphite pencil on composition board, 25 1/2 x 21 1/4 inches, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Bequest of Richard S. Zeisler

In the unsettled time when these paintings were made, the art world was sharply divided, with a few exceptions, between artists espousing experimentation and abstraction and those who rejected them in favor of tried-and-true methods and iconography. Jackson Pollock was already several years into his drip paintings, and Willem de Kooning was about to incite the wrath of the critical mob for returning to the figure with “Woman I” (1950-1952). Greene eventually converted in his late 30s to abstraction, but Wilde remained true to a meticulous, image-based surrealism.

Of the three, Graham looked like the odd man out. A Polish immigrant via Kiev and Moscow (born Ivan Gratianovich Dombrowski in 1886), and a former lawyer, cavalry officer, and, briefly, prisoner of the Bolsheviks, he was a master of reinvention and — crucially for his future associations with forward-thinking painters — a frequent visitor to the Russian businessman Sergei Shchukin and his unsurpassable collection of the School of Paris. It was this deep immersion in European Modernism, supplemented by trips to Paris, that became Graham’s calling card to his new American friends.

As I asserted in my earlier piece, there was arguably no one more consequential than Graham to the development of American Postwar Modernism, making his mark as an “artist, writer, lecturer, self-styled theorist, collector, advisor, curator, impresario, and lifeline from the hotbeds of European avant-garde art to the burgeoning modernist scene in the U.S.”:

In the catalogue for the traveling exhibition American Vanguards: Graham, Davis, Gorky, de Kooning, and Their Circle, 1927-1942 (2012), the curator and historian Karen Wilkin describes Graham’s role in the embryonic New York art world as “the crucial link in a chain of friendships, the source of vital information, the catalyst in a significant development, the provider of useful advice, the instigator of new connections in an ever-enlarging web of artist-colleagues.”

Graham was a staunch friend and ally of Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and David Smith. In 1942 he organized French and American Paintings, a landmark exhibition in which he included himself, Davis, and de Kooning, along with Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico, and Georges Rouault. The show also led to the fateful meeting between two of its lesser-known participants, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock.

Unlike Fairfield Porter, a writer and artist who formed friendships with the avant-gardists of his day but practiced a genteel painterly realism himself, Gorky continually pushed his own work into the crosscurrents of Modernism until his moment of disillusionment.

John D. Graham, “Untitled (Face of a Woman; Portrait of Anni Albers)” (1939), oil on canvas, 25 x 20 inches, Collection of Eric Cohler, New York

The exhibition John Graham: Maverick Modernist at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, Long Island, is a unique opportunity to explore the work of an artist who has hovered on the margins of the Modernist narrative for more than a half-century, when he isn’t forgotten altogether.

Organized by Alicia G. Longwell, who wrote her dissertation on Graham, and guest co-curator Karen Wilkin — who was responsible, along with William C. Agee and Irving Sandler, for the above-cited American Vanguards exhibition — Maverick Modernist takes a deep dive into Graham’s background as an artist, a career he began in earnest when, at the age of 35, he enrolled in the class of the Ashcan School painter John Sloan at the Art Students League in New York City.

Despite the lessons Graham gleaned from his teacher, and the respect he held for him, Sloan represented the past, while an artist like Davis heralded the future. And so Graham pushed his art in the direction of American Cubism, though at a time — the early to mid-1920s — when its Parisian originators had abandoned it for a clunky Neoclassicism as part of the “return to order” following the devastation of World War I.

The paintings that Graham produced during the 1920s seesawed between Synthetic Cubism and unvarnished Neoclassicism, with a touch of Surrealist whimsy thrown in. Peppered by influences, with Picasso’s long shadow never very far away, he had entered into a lengthy apprenticeship comparable to Gorky’s devotion to Cézanne and Picasso, which ended in a similarly startling late-in-life breakthrough.

John D. Graham, “Coffee Cup (La tasse de café)” (1928), oil and sand on canvas, 19 5/8 x 25 1/2 inches, Collection of Josep Pl Carroll and Dr. Roberta Carroll

A canvas such as “Coffee Cup” (1928), is all earth tones and off-whites, with bluntly volumetric forms reminiscent of the back-to-basics Valori plastici group active in Italy at around the same time, as are a set of nudes painted the same year. But there is also a pastel-colored, Metaphysical-style “Interior” (ca.1928), à la de Chrico, that flaunts its deep perspectival space. A fanciful village-and-seascape, “Palermo” (1928), could have been painted by Maurice Utrillo.

While some of his textural, white-on-white Cubist paintings from the following year are quite strong (“Still Life with Pipe” and “Peinture,�� both 1929, and “Nature Morte,” 1929-1930), they barely deviate from Picasso’s style. As he enters the 1930s, Graham’s artistic output becomes, if anything, more transitional, with works like the solidly geometric abstraction “Red Square” (1934) — which is actually a red trapezoid — standing in direct opposition to an untitled, outsized Neoclassical head of Anni Albers from 1939. (The pairing of these two images on the same double-page spread in the catalogue seems like an inside joke about Albers’s husband, Josef, who would begin his famous Homage to the Square series ten years after Graham painted Anni’s portrait.)

John D. Graham, “Still Life with Pipe” (1929), oil on canvas, 13 1/4 x 23 inches, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Mr. and Mrs. George R. Brown and George S. Heyer, Jr.

During this time, in 1937, Graham published his book, Systems and Dialectics in Art, which would become an enormous influence on Pollock. In his catalogue essay for the current exhibition, William C. Agee notes, “Graham espoused the importance of delving into the unconscious, through a personal écriture.” The psychodynamics of the Abstract Expressionists pivoted on that idea, which is also linked to Graham’s eventual change of heart about contemporary painting.

That change took him in an unexpected, some would say reactionary direction, but its origin in the expression of the unconscious through “a personal écriture,” or handwriting, is what makes his late figurative paintings — with their cross-eyed women and flat, frontal, compositions — so fundamentally different from those of a Magic Realist like John Wilde.

In 1946 — just four years after he organized French and American Paintings — Graham wrote an unpublished text (characterized as a “diatribe” by Wilkin in her catalogue essay) entitled “The Case of Mr. Picasso.” Having already denounced, in his personal letters, the painter widely considered the king of 20th-century art (“charlatan” was his epithet of choice), Graham (again, from Wilkin’s essay) “expanded on his objections, castigating artists for emphasizing […] formal concerns: ‘Young painters, nowadays, are wont to talk about pure form, plastic values, plane-tension, texture, space, design and whatnot. These things are merely means and not aims in themselves.’”

In this passage, Graham comes off not so much as anti-Modernist as anti-Formalist, which makes him, perhaps, the first fully formed Postmodernist. Digging deeply into his own psyche, he was able to cast off the pastiche of styles that had been crowding his mind’s eye, and follow his own peculiar path.

Graham called Nicolas Poussin his teacher; Wilkin also mentions the influence of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the figure paintings of Gorky and de Kooning, and the frescoes of Minoan Crete, while Agee cites the Italian Mannerist Bronzino and the Neue Sachlichkeit painter Christian Schad.

It’s interesting that Agee brings up not only Schad, but also the German artist’s influence on the “all but forgotten” American movement of Magic Realism, calling it “a distant relative of the New Classicism, which had begun with Picasso’s 1914 The Painter and His Model,” a work that is partially painted and partially drawn. To compare Graham’s realism to Schad’s New Objectivity or Wilde’s Magic Realism is to affirm how unrealistic it actually is.

Both styles, however different (Schad was an exquisite chronicler of Weimar decadence, while Wilde went after dreamlike, virtuosic mimesis and superficial shocks), were based in an optical examination of the real world, while Graham’s work is undeniably a mental projection. You can sense him feeling out the forms as he made them, their tumid sensuality feeding off his immersive eroticism. (Wilkin adds parenthetically, “Graham explained the crossed eyes to an acquaintance as documenting his observations of women at peak sexual ecstasy.”)

The first mature figurative works encountered in the exhibition are drawings hung across one side of a corridor dividing the rooms holding Graham’s early, scattershot experiments from a long, grand gallery displaying the more consistent and polished later paintings.

In this informal space, the notion of the paper’s surface as a theater of ideas (abetted by vitrines filled with scribbled-over sketchbooks) comes through more clearly than it would if the drawings were sidelined as minor works in a painting gallery — especially the wildly complex “Donna Losca” (ca.1959), whose crossed eyes look more poignant and contemplative than comic.

John D. Graham, “Marya (Donna Ferita; Pensive Lady)” (1944), oil on Masonite, 48 x 48 inches, Private Collection, Purchase, New York

Amid bits of collage and snippets of writing, phallic widgets tumble around her shoulders and bodice; a miniature sword protrudes from her mouth; long pins pierce her temple and forehead; and a short laceration splits the skin at the base of her neck.

Evidence of a sadistic streak reappears here and there throughout the exhibition: another neck incision is found in the watercolor, gouache, and ink drawing, “The Flail of the Lord” (ca.1950), and the Renaissance-style “Stallion” (ca.1951), in ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and crayon on tracing paper, has been shot with three arrows through the side and rump. In the large (four by four feet) oil on masonite painting, “Marya (Donna Ferita; Pensive Lady)” (1944), one of the masterworks in the show, the wound (of the “donna ferita” — “wounded woman”) is a red gash across her right wrist.

A wall text explains that Graham’s work after 1944 “drew heavily on such sources as the occult, bloody Christian martyrdom, and the realms of numerology and astrology.” It also states that the artist’s disavowal of Picasso “was in no way a rejection of avant-garde principles but a desire to establish another way of making modern art.”

Graham’s “another way of making modern art” was not a step backward, but a step inward — essentially the same route taken by the Abstract Expressionists, but toward a much different end. His psychosexual compulsion, sublimated in his paintings more than in his drawings, lead him to make off-the-wall images scattered with even stranger details that are convincing despite their seeming randomness; we identify with his dark need to destroy the very order he’s creating.

How else to explain our ease in accepting the bloody gash on the wrist of an otherwise classically serene portrait, or the black raccoon-eyes mask worn by the sitter in “Mascara” (1950)? Or the pronounced sexual undercurrent running through the double-portrait, “Two Sisters” (1944), from the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, with its wickedly crossed eyes, bared breasts, and juiced-up color a blush shy of garish?

John D. Graham, “Mascara” (1950), oil on canvas, 23 7/8 x 19 5/8 inches, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen

“Kali Yuga,” with her outlandishly loopy hairdo, is here as well, on loan from the Whitney. Away from its previous context, in the company of its peers, what made this painting distinct from Wilde’s and Greene’s — a picture plane that acts not as an invisible fourth wall but as a solid arena of vibrant forms — infuses the late portraits with an unruly sense of life. They are not ensconced inside a painterly illusion, but encroach into your reality through the force of their lurid magnetism.

In these works, which aggressively foreground the materiality of paint as much as those of his abstract counterparts (and it’s telling that they were done on such resistant supports as Masonite and composition board, rather than flexible, absorbent canvas), Graham followed Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim to “make it new” by stripping his art down to the fundamentals of line, color, and shape, and freeing his hand to be guided by intimate obsessions.

Rejecting what he viewed as the dead end of abstraction along with the trickery of pictorial artifice — and conversely, accepting pigment and surface as painting’s only reality — Graham opened his work up to a personal, often bizarre realm that, through his mastery of “pure form, plastic values, plane-tension, texture, space, design and whatnot,” remains riveting in its beauty and presence, while other equally imaginative but less rigorously interrogated visions fade into irrelevance.

John Graham: Maverick Modernist continues at the Parrish Art Museum (279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, New York) through July 30.

The post John D. Graham and “Another Way of Making Modern Art” appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2spf1io via IFTTT

0 notes