#or just a great fodder for creativity and narrative play

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I don't get why people hate the timeline so much, its not like you can't pretty much completely ignore it when you play the games. The only time it even approaches mattering to the story is when there is an explicit sequel like botw and totk or zelda and zelda 2

Hey sorry your ask got lost in the sauce of my broken tumblr, but: yeah!

I mean, I get why in some sense. It's been a heated point of debate and I think some people understandably resent the space it has taken not only in fandom discourse, but in how people began to understand the game and its narrative aesthetic choices. There is such a thing as over-rationalizing everything to hard logic, and sometimes it's just not the fandom for that --especially when you begin to forget it's all just fan theory and start to forget what the games are supposed to be like and evoke beyond just strict facts displayed in a linear way.

What I think bugs me with TotK in particular is that it both evokes and relies on continuity and the idea of a timeline, of archeology, of history itself, while being so loose and vacant with it that it both is doing Timeline Shit while also completely failing to understand why some parts of the fandom were invested in Timeline Shit to begin with.

But that's just my two cents of course!

#asks#tloz#timeline#totk critical#thanks for the ask!#I do... feel two ways about that myself#I think pure evocation is genuinely one of zelda's greatest storytelling strengths#that mood is sufficient and enough in itself and doesn't always need justification#it is the way the games center story --and that's genuinely wonderful and a strong take on narrative in games#as something freeflowing and accompanying gameplay rather than the opposite#and to ignore that and focus on hard facts all of the time kind of misses the point of the games' stories to a degree#BUT#I also get quite annoyed at the weird condescencion towards fans that do decide to engage with the stories more factually#especially since this is either revelatory regarding some of nintendo's choices#(that the aesthetics of evil are so tied to The Desert TM while taking so many inspirations from european fairy tales for example)#(it's not neutral even if we ignore ingame “lore”)#or just a great fodder for creativity and narrative play#and it is a part of the IP too!! just as much as dungeons and items and musics and curiosity-driven exploration!!#I do have beef with people not resonating with that aspect thinking others that do so are just stupid or childish#and that you can only have an enlightened relationship with zelda if you like it “the right way”#(which is somehow always mechanics/logic-driven which is. interesting to me.)#(or in a completely passively aesthetic way as in “I like fairies they're pretty”)#but you know it's the weird Triforce Shirt Dude stigma thing#that notion that you can (and must!) Love Zelda Deeply and Defensively#but you cannot be *passionate* about Zelda#then it's weird and immature#I don't know I feel like there's a lot to analyze in that arbitrary dychotomy#anyway sorry for the mega novel in the tags!!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Freewriting

Freewriting - the practice of writing without a prescribed structure, which means no outlines, cards, notes, or editorial oversight.

In freewriting, the writer follows the impulses of their own mind, allowing thoughts and inspiration to appear to them without premeditation.

Benefits of Freewriting

CREATIVE EXPRESSION

Many writers embrace freewriting as a way to find unexpected inspiration.

Outlines and notes can be wonderful for the purpose of staying on task, but they can sometimes stifle the creativity that comes from free association.

This is where freewriting comes in.

By starting with a rough idea, but without pre-planned details, a writer opens themself up to discovery and new found inspiration.

WRITER'S BLOCK

Writers who feel in a style rut, or who actively experience writer’s block, may benefit from a freewriting exercise as part of their formal writing process.

By forcing themselves to put words on a page, a writer may be able to alleviate their anxiety about writing and allow them to be more creative.

SPEED

Freewriting is typically faster than other forms of draft writing or outlining.

Because you are simply writing without a strict form to follow and without organizing your thoughts.

5 Tips and Techniques for Freewriting

JUST WRITE

Any writing coach or writing teacher will tell you that you must segregate your writing process from your editing process.

When it comes to freewriting, first drafts are repositories for every idea that comes to mind, however vague or tangential.

Don’t worry about word count, don’t worry about market viability, don’t worry about sentence structure, don’t even worry about spelling.

Unleash your creativity, let the ideas flow, and trust that there will be time for editing later.

This rule applies whether you wish to write a novel, a play, a short story, or a poem.

GATHER TOPICS BEFOREHAND

Freewriting doesn’t mean you write without having an idea about your topic/story.

Even the most committed freewriters tend to have some degree of a prewriting technique - they ruminate on their subject matter in a broad, general sense.

You don’t have to pre-plan details before you start writing, but it helps to know in the broadest sense what it is you think you’ll write about.

TIME YOURSELF

If you are experiencing writer’s block, commit to getting words down on the page within the first 60 seconds of writing.

Perhaps those first words will not yield anything, but think of them metaphorically as the first drops you put into the five gallon bucket that is your novel.

There is nothing to be gained by staring at a page or computer screen for any great period of time.

COMBINE FREEWRITING WITH TRADITIONAL OUTLINES OR NOTES

While it can be quite satisfying to say that one wrote an entire novel using freewriting techniques (as Jack Kerouac is said to have done with On the Road) what readers care about most is the quality of your writing.

With this in mind, start a project with a substantive freewriting session.

Depending on what you produce, you may want to use that content as fodder for a formal process that more closely conforms to the traditional rules of writing (outlines, notes, etc.).

Let that outline or set of notes guide the remainder of your writing on the project.

Remember, too, that you can always toggle back to freewriting at any point.

BRING IDEAS TO YOUR SESSIONS

Some writers, particularly poets, begin sessions with no ideas or themes they plan to tackle—they simply begin writing with the first word or phrase that comes to mind, and then they let the process unfold from there.

While you can work toward this point, if you’re new to the medium of writing and are seeking to unleash the writer within, plan your freewriting sessions when you have a strong idea of your story or theme.

The most effective writing has thematic or narrative consistency, and starting with a small germ of an idea may help you achieve that consistency.

Source ⚜ Writing Notes & References

#free writing#on writing#writing tips#writeblr#spilled ink#dark academia#writing reference#writing advice#writing inspiration#creative writing#writer's block#writing exercise#writing ideas#literature#writers on tumblr#poets on tumblr#writing prompt#poetry#adélaïde labille-guiard#writing resources

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yesterday, @ariel-seagull-wings and I were discussing fantasy works inspired by fairy tales and fairy tales crossovers.

We then discussed about what would be ours Do's e Don'ts of the genre. She then suggested I should post it to get the opinion of my other mutuals.

In a fantasy work inspired by fairy tales and that used fairy tale crossovers, what would be your list of things that absolutely should be made and things that absolutely shouldn't be made?

This is my list

Do's

1 - Be creative. Don't just use the Disney versions of the stories

2 - Fairy tales are the genre with the highest female presence in folklore in general. Women have to play a central role in the narrative otherwise everything about it falls apart.

3 - Use lesser known stories. I assure you, there are more stories to be explored than Cinderella and Snow White.

4 - Add depth to the tales we already know. Explore all the consequences and possibilities of these classics

5 - I want at least some worldbuilding. How do the kingdoms work? What is the history of the magical creatures? Is this Earth or a separate world? Are they in an alternate history where all myths are real?

Don't

1 - Avoid the "Strong Female Charactertm" like the plague. If I see another "I'm a princess but I don't need to be saved" I'm going to scream. For the gods' sake, just show us the physical and emotional strength of the heroine already. Enough with the pandering.

2 - Not every female character has to be a She-Ra to be strong and inspiring. Treat your female characters like real people.

3 - If magic is a consistent and normal part of your world, stop making people so shocked every time it happens.

4 - Avoid the good and beautiful races and the bad and ugly races. If you need cannon fodder for your heroic character to slaughter without guilt, use political or ideological factions. At least you reduce the more problematic connotations of making a whole race being born inherently evil. There is a great different between saying "I want to kill all Nazis" or "I want to kill all Fascists" to "I want to kill all Germans" or "I want to kill all Italians"

5 - Wordbuilding is not the same thing as cynicism. Your world can certainly be a little utopian and romantic and still be well characterized. It's still a fairy tale for gods' sake. Your worlds can be a little idealized and still feel real. Worldbuilding shouldn't mean that everyone is a jerk and everything sucks.

Reblog this with your Do's and Don'ts

@ariel-seagull-wings @princesssarisa @angelixgutz @the-blue-fairie @thealmightyemprex @natache @tamisdava2 @amalthea9

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey all!

Let’s talk about collaborative storytelling. It’s been one of the best things for my creative practice outside of schoolwork.

I’ve been playing D&D since about 2017. Lots of great character moments have come from that, and I love telling a story with my friends! We all get very invested in the personal lives of our characters, which means lots of fodder for sketching. Lately my friends and I have also been really into Final Fantasy 14. The game gets you really hooked on your own character, and I don’t think I’ve sketched this much in a long, long time. I have so many ideas and so little time, but at least I’m being motivated to draw and expand my practice, even if it’s just for drawing me and my friend’s characters.

On a deeper level, I think it shows how art is a communal process -- we are all meant to partake in it, whether we are creating or not. It’s something we can use to connect with each other. Whenever I make art of a friends’ character and they get excited, I feel so warm and fulfilled. From a historical standpoint, we are creatures that are greatly motivated by narrative. It’s built into our blood, and making a story with my friends together feels like partaking in something ancient and divine. It’d be great if we could have even more art-making opportunities in our communities.

How do you connect with other people through art?

All for now.

0 notes

Text

Watching The Queen’s Gambit; on the Remarkable Unexceptionality of Beth Harmon

‘With some people, chess is a pastime. With others, it is a compulsion, even an addiction. And every now and then, a person comes along for whom it is a birthright. Now and then, a small boy appears and dazzles us with his precocity, at what may be the world’s most difficult game. But what if that boy were a girl? A young, unsmiling girl, with brown eyes, red hair, and a dark blue dress? Into the male-dominated world of the nation’s top chess tournaments, strolls a teenage girl with bright, intense eyes, from Fairfield High School in Lexington, Kentucky. She is quiet, well-mannered, and out for blood.’

The preceding epigraph opens a fictional profile of Beth Harmon featured in the third episode of The Queen’s Gambit (2020), and is written and published after the protagonist — a teenage, rookie chess player, no less — beats a series of ranked pros to win her first of many tournaments. In the same deft manner as it depicts the character’s ascent to her global chess stardom, the piece also sets up the series’s narrative: this is evidence of a great talent, it tells us, a grandmaster in the making. As with most other stories about prodigies, this new entry into a timeworn genre is framed unexceptionally by its subject’s exceptionality.

Yet as far as tales regaled about young chess wunderkinds go, Beth Harmon’s stands out in more ways than one. That she is a girl in a male-dominated world has clearly not gone unremarked by both her diegetic and nondiegetic audiences. That her life has thus far — and despite her circumstances — been relatively uneventful, however, is what makes this show so remarkable. After all, much of our culture has undeniably primed us to expect the consequential from those whom we raise upon the pedestal of genius. As Harmon’s interviewer suggests in her conversation with Harmon for the latter’s profile, “Creativity and psychosis often go hand in hand. Or, for that matter, genius and madness.” So quickly do we attribute extraordinary accomplishments to similarly irregular origins that we presume an inexplicability of our geniuses: their idiosyncrasies are warranted, their bad behaviours are excused, and deep into their biographies we dig to excavate the enigmatic anomalies behind their gifts. Through our myths of exceptionality, we make the slightest aberrations into metonyms for brilliance.

Nonetheless, for all her sullenness, non-conformity, and her plethora of addictions, Beth Harmon seems an uncommonly normal girl. No doubt this may be a contentious view, as evinced perhaps by the chorus of viewers and reviewers alike who have already begun to brand the character a Mary Sue. Writing on the series for the LA Review of Books, for instance, Aaron Bady construes The Queen’s Gambit as “the tragedy of Bobby Fischer [made] into a feminist fantasy, a superhero story.” In the same vein, Jane Hu also laments in her astute critique of the Cold War-era drama its flagrant and saccharine wish-fulfillment tendencies. “The show gets to have it both ways,” she observes, “a beautiful heroine who leans into the edge of near self-destruction, but never entirely, because of all the male friends she makes along the way.” Sexual difference is here reconstituted as the unbridgeable chasm that divides the US from the Soviet Union, whereas the mutual friendliness shared between Harmon and her male chess opponents becomes a utopic revision of history. Should one follow Hu’s evaluation of the series as a period drama, then the retroactive ascription of a recognisably socialist collaborative ethos to Harmon and her compatriots is a contrived one indeed.

Accordingly, both Hu and Bady conclude that the series grants us depthless emotional satisfaction at the costly expense of realism: its all-too-easy resolutions swiftly sidestep any nascent hint of overwhelming tension; its resulting calm betrays our desire for reprieve. Underlying these arguments is the fundamental assumption that the unembellished truth should also be an inconvenient one, but why must we always demand difficulty from those we deem noteworthy? Summing up the show’s conspicuous penchant for conflict-avoidance, Bady writes that:

over and over again, the show strongly suggests — through a variety of genre and narrative cues — that something bad is about to happen. And then … it just doesn’t. An orphan is sent to a gothic orphanage and the staff … are benign. She meets a creepy, taciturn old man in the basement … and he teaches her chess and loans her money. She is adopted by a dysfunctional family and the mother … takes care of her. She goes to a chess tournament and midway through a crucial game she gets her first period and … another girl helps her, who she rebuffs, and she is fine anyway. She wins games, defeating older male players, and … they respect and welcome her, selflessly helping her. The foster father comes back and …she has the money to buy him off. She gets entangled in cold war politics and … decides not to be.

In short, everything that could go wrong … simply does not go wrong.

Time and again predicaments arise in Harmon’s narrative, but at each point, she is helped fortuitously by the people around her. In turn, the character is allowed to move through the series with the restrained unflappability of a sleepwalker, as if unaffected by the drama of her life. Of course, this is not to say that she fails to encounter any obstacle on her way to celebrity and success — for neither her childhood trauma nor her substance-laden adolescence are exactly rosy portraits of idyll — but only that such challenges seem so easily ironed out by that they hardly register as true adversity. In other words, the show takes us repeatedly to the brink of what could become a life-altering crisis but refuses to indulge our taste for the spectacle that follows. Skipping over the Aristotelian climax, it shields us from the height of suspense, and without much struggle or effort on the viewers’ part, hands us our payoff. Consequently lacking the epochal weight of plot, little feels deserved in Harmon’s story.

In his study of eschatological fictions, The Sense of an Ending, Frank Kermode would associate such a predilection for catastrophes with our abiding fear of disorder. Seeing as time, as he argues, is “purely successive [and] disorganised,” we can only reach to the fictive concords of plot to make sense of our experiences. Endings in particular serve as the teleological objective towards which humanity projects our existence, so we hold paradigms of apocalypse closely to ourselves to restore significance to our lives. It probably comes as no surprise then that in a year of chaos and relentless disaster — not to mention the present era of extreme precariousness, doomscrolling, and the 24/7 news cycle, all of which have irrevocably attuned us to the dreadful expectation of “the worst thing to come” — we find ourselves eyeing Harmon’s good fortune with such scepticism. Surely, we imagine, something has to have happened to the character for her in order to justify her immense consequence. But just as children are adopted each day into loving families and chess tournaments play out regularly without much strife, so too can Harmon maintain low-grade dysfunctional relationships with her typically flawed family and friends.

In any case, although “it seems to be a condition attaching to the exercise of thinking about the future that one should assume one's own time to stand in extraordinary relation to it,” not all orphans have to face Dickensian fates and not all geniuses have to be so tortured (Kermode). The fact remains that the vagaries of our existence are beyond perfect reason, and any attempt at thinking otherwise, while vital, may be naive. Contrary to most critics’ contentions, it is hence not The Queen’s Gambit’s subversions of form but its continued reach towards the same that holds up for viewers such a comforting promise of coherence. The show comes closest to disappointing us as a result when it eschews melodrama for the straightforward. Surprised by the ease and randomness of Harmon’s life, it is not difficult for one to wonder, four or five episodes into the show, what it is all for; one could even begin to empathise with Hu’s description of the series as mere “fodder for beauty.”

Watching over the series now with Bady’s recap of it in mind, however, I am reminded oddly not of the prestige and historical dramas to which the series is frequently compared, but the low-stakes, slice-of-life cartoons that had peppered my childhood. Defined by the prosaicness of its settings, the genre punctuates the life’s mundanity with brief moments of marvel to accentuate the curious in the ordinary. In these shows, kindergarteners fix the troubles of adults with their hilarious playground antics, while time-traveling robot cats and toddler scientists alike are confronted with the woes of chores. Likewise, we find in The Queen’s Gambit a comparable glimpse of the quotidian framed by its protagonist’s quirks. Certainly, little about the Netflix series’ visual and narrative features would identify it as a slice-of-life serial, but there remains some merit, I believe, in watching it as such. For, if there is anything to be gained from plots wherein nothing is introduced that cannot be resolved in an episode or ten, it is not just what Bady calls the “drowsy comfort” of satisfaction — of knowing that things will be alright, or at the very least, that they will not be terrible. Rather, it is the sense that we are not yet so estranged from ourselves, and that both life and familiarity persists even in the most extraordinary of circumstances.

Perhaps some might find such a tendency towards the normal questionable, yet when all the world is on fire and everyone clambers for acclaim, it is ultimately the ongoingness of everyday life for which one yearns. As Harmon’s childhood friend, Jolene, tells her when she is once again about to fall off the wagon, “You’ve been the best at what you do for so long, you don’t even know what it’s like for the rest of us.” For so long, and especially over the past year, we have catastrophized the myriad crises in which we’re living that we often overlook the minor details and habits that nonetheless sustain us. To inhabit the congruence of both the remarkable and its opposite in the singular figure of Beth Harmon is therefore to be reminded of the possibility of being outstanding without being exceptional — that is, to not make an exception of oneself despite one’s situation — and to let oneself be drawn back, however placid or insignificant it may be, into the unassuming hum of dailiness. It is in this way of living that one lives on, minute by minute, day by day, against the looming fear and anxiety that seek to suspend our plodding regular existence. It is also in this way that I will soon be turning the page on the last few months in anticipation of what is to come.

Born and raised in the perpetually summery tropics — that is, Singapore — Rachel Tay wishes she could say her life was just like a still from Call Me By Your Name: tanned boys, peaches, and all. Unfortunately, the only resemblance that her life bears to the film comes in the form of books, albeit ones read in the comfort of air-conditioned cafés, and not the pool, for the heat is sweltering and the humidity unbearable. A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, she is thus the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

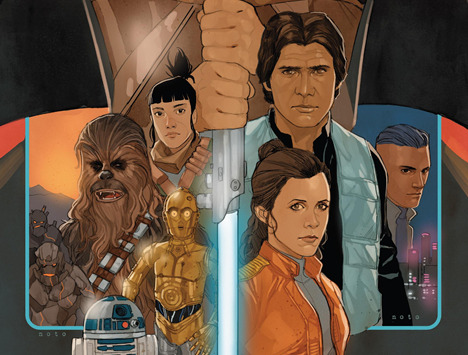

Panels Far, Far Away: A Week in Star Wars Comics 11/13-11/27/19

It’s certainly unfair for Lucasfilm to pick my first semester of grad school to start supplying us with more Star Wars content than at any other point in recorded history. Jerk move on their part. Anyways, as a result, here are three (!) weeks worth of Star Wars comics review in which: Marvel’s ongoing ends its seventy five issue run, Doctor Aphra gets her groove back, and Chewbacca knocks some heads. Hopefully I can be quicker about this in the future!

11/13/19

Star Wars #74 written by Greg Pak and art by Phil Noto

In its seventh chapter, “Rebels and Rogues” hurtles towards conclusion. The result may just be the strongest installment of an arc that has been chockfull of great ideas, but often struggled on just how to tell its sometimes overly scattered story. With the different teams now in open communication with one another and each fighting for their lives in desperate situations, writer Greg Pak’s take on the galaxy far, far away has never felt more a live and energetic.

We hop between narratives with surprising ease and elegance and the flow of the story is easy to follow, high energy, and positively fun. Han, Leia, and Dar Champion are flying for their lives in a defenseless ship against an Imperial star destroyer, Luke and Warba are in route to the planet’s rebels but with an Imperial patrol of Stormtroopers riding velociraptors right on their tale, and Threepio and Chewbacca are right in the center of a growing conflict between the rock people of K43 and Darth Vader himself.

Threepio’s arc here still remains the most fascinating stuff in “Rebels and Rogues.” For the first time in a long time, old goldenrod feels like he has an emotional story all his own and it culminates in a moment of self-sacrifice that capitalizes off all the themes of sentience and personhood that this surprisingly delightful subplot has been playing with since day one.

The promised Chewbacca/Darth Vader showdown on the cover doesn’t occur until the comics final pages but it sets up what should be a killer finale. Noto draws a suitably visceral encounter and no other panel in this creative team’s legacy will likely spark as much joy as Chewie spiking a boulder off of the Sith Lord’s ebony helmet.

Score: A-

Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order: Dark Temple #4 written by Matthew Rosenberg and art by Paolo Villanelli

At the time of this writing, I’ve actually finished playing Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order. The first single player Star Wars game in over a decade provides a very fun and rewarding experience that is populated with some truly outstanding characters. The game also shows that its tie-in comic, Dark Temple is surprisingly more consequential than one might have originally thought. Sure, Cere and Eno Cordova were known characters in the game from the start, but Dark Temple sees the two encountering numerous elements from Fallen Order for the first time.

Even outside the comic’s surprising consequence to the game it draws from, Dark Temple continues to be a very entertaining prequel era narrative. Even four issues in, writer Matthew Rosenberg is still providing us with new information and twists that upend our understanding of what exactly is going on. Cere and Cordova may have gotten involved in something bigger than they originally anticipated and there is more on the line than freedom for Fylar. Rosenberg has weaved a complex web and just what exactly lies within the titular temple is just as much a mystery now as when it started.

It also helps that this comic is arguably the best looking Star Wars comic on the stands now. Paolo Villanelli has always excelled at drawing dynamic and well choreographed action sequences and he truly shines here as the violent conflict between Flyar and the DAA corporation explodes into full blown war. Villanelli is great at creating a sense of motion and scale and these moments of larger conflict are filled to the brim with well designed characters and explosive energy. Colorist Arif Prianto makes the comic feel like it comes ablaze too with multicolored embers peppering each panel.

Between the surprisingly complex story and the killer art, Dark Temple has quickly evolved into one of the stronger tie-in comics that Star Wars has released in recent memory and a significant improvement on both creator’s previous works in the franchise. Its final issue may not stick the landing, but this is a comic that is well worth considering picking up.

Score: B+

Star Wars Target Vader #5 written by Robbie Thompson and art by Cris Bolson, Robert Di Salvo, and Marco Failla

So turns out the Hidden Hand isn’t the rebellion? I’m very lost at this point. The mysterious crime organization that has been at the center of Target Vader from its start has always been its biggest head scratcher. A last panel reveal at the end of the comic’s first issue heavily hinted that the Hidden Hand was actually just an organization used by the Alliance to work in the criminal underworld. Over the past few issues, we have been given to doubt this reading, until now, where this theory is thrown out the door. Turns out the Hidden Hand may have older and more mysterious origins, but now we are just as lost as ever.

It speaks to the overall aimlessness of Target Vader. Despite the violent thrills of last issue, this miniseries has still been a mostly confused and overly long affair. Beilert Valance is still a mostly dull protagonist and his quest to neutralize Vader feels even more muddled than ever before. Writer Robbie Thompson does some work to try to remedy this situation by giving us an issue that is split between retelling Valance’s past and maiming by the Imperial military and the present where he is now caught between the grip of the Empire and the Rebel Alliance. It creates an interesting scenario for our central anti-hero, but ultimately fails to reveal much enlightening about Valance as a person. We may know why he is a grumpy, angry loaner by this point, but it doesn’t make his relatively one-note behavior any more interesting.

It also doesn’t really help that we have three guest artists on board instead of Stefano Landini. Marco Failla’s pencils may do a good enough job of approximating Landini’s style, but as a whole the result is a bit jarring as the comic never establishes a clear visual consistency. Combined with the fact that we already lost Marc Laming after issue one, this just adds to the weirdly confused reading experience that Target Vader has maintained to this point.

We have seen this comic work. Last issue’s installment was a brutally realized explosion of violent chaos, but we only have one issue now to really bring it all together, and I’m worried that Target Vader may not be up to the task of making this long, strange voyage worth it.

Score: C+

11/20/19

Star Wars #75 written by Greg Pak and art by Phil Noto

All roads lead to K43. In its eighth and final chapter, “Rebels and Rogues” sees all our team members converge on the rocky moon for one climactic stand against Darth Vader and the Empire. In this extra sized finale, Greg Pak and Phil Noto try their best to pull the disparate threads of this arc together while also delivering a satisfying finale. The result proves fun, very strange, and ultimately forgettable. It ends with a summation of this run as a whole: filled with smart art and ideas, but lacking in standout storytelling beats to leave a lasting impression.

Some of the disappointment comes from the fact that much of this issue comes down to our various cast members beating up on Darth Vader. We open with the final blows of Chewbacca and Vader’s brawl which Noto clearly enjoyed bringing to life, but much of the rest of the issue resorts to the extended ensemble blasting away at him in various set pieces. It plays out like a miniature version of 2016’s Vader Down, but lacking in the edge and thrills of that original crossover.

There’s also some strange choices made with the rock people of K43 that don’t entirely gel with what came before. Part of what made these characters so refreshing throughout this story arc has been how Pak used their existence to challenge our characters’ concepts of sentience and to allow C-3PO to bond with another group of non organic life that is similarly overlooked. This fun play continues, but the conflict of it all is handwaved away in a manner that feels unusually flippant. Given the amount of effort put into finding a way around murdering this race, Pak introduces a last minute plot detail that makes it all feel unnecessary and that’s before the giant planet sized stone giant appears.

Yes, this comic gets very weird and it’s certainly fun, but it feels more than a little scattered and chaotic in a comic that already feels all over the place.

With that, we bid goodbye to this short but enjoyable era of Marvel’s Star Wars ongoing. While Empire Ascendant will presumably be the final issue of the main series, with it being rebooted for a new post Empire Strikes Back ongoing headed by Charles Soule and Jesus Saiz sometime in January, there is a sense of finality to this creative team’s last chapter aboard. Pak and Noto prove a fun bunch and had a great sense of playfulness and scope to this ongoing during its final days even if the execution wasn’t always immaculate. I’m glad to hear that Pak will be staying around to write the next volume of Darth Vader. He has some big shoes to fill, but if the heights of this comic are any indication, he is capable of the same spectacle and intrigue as past creators.

Score: B

11/27/19

Star Wars Adventures #28 written by John Barber and Michael Moreci and art by Derek Charm and Tony Fleecs

Chewbacca’s adventures with his porg sidekick, Terbus, are pretty much perfect fodder for an all-ages Star Wars comic. Given how strong Adventures’ visual storytelling has been since day one, having two protagonists who speak through grunts, squawks, and body language is right up this teams’ alley. Yes, it’s cutesy and yes it is a bit simple, but there is undeniable charm in the way Derek Charm draws us through the liberation of Kashyyyk. It may not be as visually inventive as last issue, but the way that Chewbacca hops through the forest and takes on First Order baddies is still illustrated with the same energy and personality.

There is a bit of tonal whiplash here though. While it’s hard not to be won over by Porg salutes and Wookiees knocking heads, there are moments where the enslavement of the Wookiee population is presented as an all too real possibility. The lighter, more playful execution of this issue may do a lot to make this subject matter more palatable for younger readers, but one wonders if this should have been the direction that the story went with at all.

Michael Moreci’s droid adventure is more tonally cohesive and certainly also a fun time, but it lacks the standout visuals and heart of the Chewbacca section. Last issue succeeded by pairing the under appreciated droids with another outcast that also was invisible to the First Order, but the events here are less concerned with character and theme and more so with the fun action of their plan. All the same, it’s still a decent read and sure to delight younger readers.

Score: B

Star Wars Doctor Aphra #39 written by Simon Spurrier and art by Caspar Wijngaard

With just one issue left before the end of their tenure, Simon Spurrier and Caspar Wijngaard are pulling out all the stops for the end of Doctor Aphra. After the misstep that was “Unspeakable Rebel Superweapon,” it has been nice to see Spurrier get back in the swing of things with “A Rogue’s End” as each issue improves upon the last. Wijngaard and colorist Lee Loughridge feel more in sync here than ever before and Spurrier twists the knife as Aphra digs herself further and further into a disaster of her own making.

While she was first introduced in Kieron Gillen’s run on the title, Magna Tolvan and her relationship with Aphra have been staples of Spurrier’s run since he first stepped into the title. Here as we hurtle towards the big finish, it seems only fitting that the tortured and complex romance between these two very different souls take center stage. “A Rogue’s End” isn’t afraid to really dig into what it is about these two broken and confused women that drives their attraction to one another and just how deadly and ill advised their love, if it can be called that, is. It’s antagonistic, violent, but ultimately brimming with the sort of affection and tension that makes a good Star Wars romance sing. There is one image in particular here that is beautifully realized by Wijngaard and Loughridge and may rival the two’s first kiss for the iconography of this pairing.

It’s not all two woman coming to terms with one another under extreme circumstances, Aphra is still full speed ahead on her own mission survival. We hurtle towards a series of decisions at the issue’s end that may just cross the line into Aphra’s biggest moral slippage to date. Spurrier seems poised to deliver final judgement on what kind of person our dear rogue archaeologist may be, but knowing her and this series, the final thematic resting point is anyone’s guess. It’s a good thing that Spurrier makes the whole thing so damn fun to read and Wijngaard creates such beautiful imagery.

Score: A-

#Star Wars#Star Wars comics#review#reviews#Marvel#IDW Publishing#Doctor Aphra#Star Wars Adventures#Target Vader#Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order#Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order - Dark Temple#Greg Pak#Phil Noto#Matthew Rosenberg#Paolo Villanelli#Robbie Thompson#Cris Bolson#Robert Di Salvo#Marco Failla#Michael Moreci#Derek Charm#John Barber#Tony Fleecs#Simon Spurrier#Caspar Wijngaard

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

07172020?

So why "07172020"?

When I played "Ghost of Tsushima," last year, it gave me a lot of feels. The protagonist, Jin, was this embodiment of "good," maybe to a fault and I've really missed that, having lived through the age of the "anti-hero." In fact, you could really make an argument that PlayStation has done a great job of redefining the archetype of the "hero" for modern audiences and it's probably part of why I love their ecosystem so much.

When I was younger I was all about protagonists like Luke Skywalker (Star Wars), Prince Ashitaka (Princess Mononoke) and James Bond (007) -- characters who never dabbled in being "bad." In fact, Star Wars really paved the way for my moral concept. The idea of "light vs. dark" always resonated and I've always been a major fan of true heroes like Link (Zelda) and Cloud Strife (Final Fantasy VII).

Now, today, PlayStation has cultivated a cast of characters like Aloy (Horizon Zero Dawn), Ratchet (& Clank) and even Astro Bot. Sure, they're also known for their "gray" characters like Kratos (God of War) and Ellie (The Last of Us), but their contributions to the hero sector can't be minimized.

Enter: Jin. The ghost of Tsushima.

While I did love the game, it's not like it "blew me away." I wasn't spellbound and I'm not even sure I'd put it in my Top 10 (or anywhere close). Just to give scope, Vanillaware's "13 Sentinels" arrived shortly after and that left a bigger imprint... But what "Ghost of Tsushima" did so well is that it presented a world I wanted to explore. The true mirth of gaming is put on a pedestal in Tsushima and the devs at Sucker Punch present you with a map you just have to see every inch of. In fact, in my pursuit of the platinum trophy, I even had some monotonous moments drag me down where I thought, "Why am I even doing this?" and the answer was always, "Because you'll regret not seeing what's beyond the horizon line."

The game is teeming with beauty as Sucker Punch captured Japan's brilliance near-perfectly. There's a location set against golden trees, their leaves falling to the ground, and every time I went to that part of the map I was reminded of my time living in North Carolina. The settings are captivating and the game definitely leaves you with a sense of awe.

Inside this sandbox of mirth, Jin becomes your vehicle by which to experience such joy and he's just another one of those "good guys." Maybe a little plain and simple, but he's a good person trying to learn how to better himself and the world around him. Yes, I understand the irony of him murdering thousands of invading Mongolians, but it's a game -- suspend some belief here.

In any case, I related to Jin. Not just liked him. But I related to him. For the first time in a very long time I related to the main character and saw myself a lot throughout the game. At the time I was finishing up "Daisuki Baby" waiting for mixes wondering, "What should I do in the mean time?"

Just for fun I wrote the song "Ghost" that you hear as track 1 off "07172020." I had a little piece of music set to some "Tsushima" gameplay and ended up loving the results. But what it started as and what it became are very different.

It's hard to say if "Ghost of Tsushima" actually inspired the music, but it pressed me forward, for sure. All the song titles are references. And the game's quieter, zen-like moments inspired the introspectiveness of my EP, for sure. Again, did I sit there and try to channel Jin's search for inner peace? Definitely not. Was it in the back of my mind as I wrote equally contemplative jams? Totally.

It was Jin's sense of character that really motivated me to write something outside my comfort zone. I wanted to write music that really reached out and touched you. And in many ways I feel I succeeded. When I listen to "Reflect On..." I feel beside my own self. When I hear it I don't feel like I'm listening to my own composition. It so transcends my own creativity that I can just enjoy it as a listener. Same with "Traveler's Theme." Something about that groove just worms its way into my headspace and nests there for hours on end.

Since releasing "07172020" I haven't been able to recreate it. When I use it as a template, I flail. But I wonder if the trick was keeping something just in the back of my mind as creative fodder. The success of "07172020" isn't upon whether or not I channeled "Ghost of Tsushima" well or even properly, it's that I simply had it in mind as a concept. Dreaming of those golden leaves... contemplating the striking moonlight, dancing on flowers after dark... taking the time to revere poetry and stop for one's own enlightenment. These meditations helped propel the creation of "07172020" and I drew that inspiration directly from "Ghost of Tsushima." Does that make me a nerd? Idk. Maybe. Sure. Does it diminish the lasting effect of "07172020"s dreaminess? Nah. Why? I think it's awesome that I played a game so dope it fostered the creation of further art. Again, I didn't sit there and say, "I'm gonna make an album based off 'Ghost.'" But sometimes color palettes, narrative themes, and emotional imagery can be a great foundation. And that's exactly what "07172020" is.

I'm super proud of it. I love where it ended up. And I can't wait to do something like it again. I hope you're enjoying it as much as I am and please consider sharing it with a friend today. Just tell 'em your friend made some new music and you wanted to spread the word. I'll appreciate it forever.

xoxo,

M-T

1 note

·

View note

Text

Movies I Liked in 2019

Every year I reflect on the pop culture I enjoyed and put it in some sort of order.

Despite everything else going on in the world, 2019 was a pretty good year for movies! I saw a lot of things I really enjoyed (thanks AMC A-List!) and managed to avoid all of the live action Disney remakes. While it was hard to whittle down my list to a self-imposed/arbitrary 10, these stood out as efforts I can see myself returning to again and again.

10. The Public

This low-key release from writer/director/star Emilio Estevez is a deeply humanist look at systemic failures to address homelessness in American cities. During a bitterly cold winter in Cincinnati, a group of people decide to occupy a public library overnight rather than be forced onto the life-threatening streets, and media, law enforcement and politicians all attempt to shape the narrative. With a supporting cast including Michael K Williams, Jena Malone, Jeffrey Wright and Alec Baldwin, this one is worth seeking out (and has some great shots of Cincy as well).

9. Toy Story 4

Did Toy Story need a fourth entry? I wouldn’t have thought so, but leave it to the magicians at Pixar to find new ways to animate (eh? eh?) these beloved characters – and introduce some great new ones. With the additions of Tony Hale’s Forky, Keanu Reeves’ Duke Caboom and Key & Peele’s Bunny & Ducky, this is easily the funniest Toy Story to date. However, it still packs an emotional wallop as well: if you can get through Gabby Gabby’s final scene with dry eyes you may not have a heart.

8. The LEGO Movie 2: The Second Part

While not nearly as successful at the box office as its predecessor, the LEGO Movie sequel is just as funny, engaging and surprisingly moving. While the real-world metanarrative is no longer a surprise, the shift from parent-child relationship to that of siblings provides ample storytelling fodder that I related to even more than the original. And for the record, this was the first major movie released this year to feature a 5-year time jump – and time travel shenanigans (looking at you, Endgame).

7. The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind

Chiwetel Ejiofor adapted this true story of a boy in Malawi who devises a way to save his village from severe famine (his writing and directorial debut). The film doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities of life in under-resourced areas but also embodies hope and ingenuity that know no socioeconomic or geographic bounds.

6. A Beautiful Day In The Neighborhood

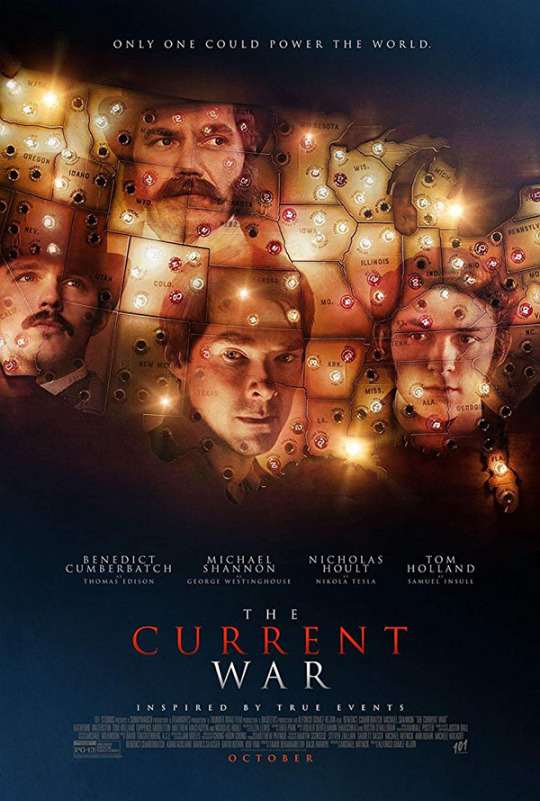

I’ll admit I was skeptical upon hearing Tom Hanks would be playing Mr. Rogers – he’s a great actor but doesn’t bear much of a resemblance in appearance or demeanor. However, his success in the part comes from not trying to technically imitate Rogers as much as embody his spirit of decency, sincerity and kindness. The fact that this is not a Rogers biopic, but rather a story of his impact on the life of a journalist who is wrestling with cynicism, anger and unforgiveness, also helps matters (what a year for movies based on longform journalism! See also: Richard Jewell, Dark Waters). The writers and director Marielle Heller take some interesting chances including a cheeky framing device and transitions using Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood-inspired miniatures that help make this film something {ahem} special.

5. The Current War: Director’s Cut

(Note: This film was originally set for release in 2017 and an unfinished version screened at film festivals that year to critical disdain. The Weinstein scandal mired it in development hell, but it got a second life in a new, finished version this fall as the “Director’s Cut.”)

This story of the “war of the currents,” as Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse raced to electrify America at the turn of the 20th century, snuck into theaters under-the-radar at the end of the summer but I am so glad I had the chance to see it on the big screen. Far from a conventional biopic or historical epic, there is a beautiful lyricism on display here with sweeping camera movements, innovative shot compositions, gorgeous use of light and color and a enveloping musical score. For a film that tracks multiple characters and locations for over a decade, there are moments of touching poignancy and intimacy that prevent it from becoming impersonal. I found it utterly compelling and transporting, though your mileage may vary.

4. Avengers: Endgame

It’s a rare Hollywood blockbuster that allows its characters time to grieve and process trauma, and even acknowledges the futility and emptiness of revenge. Endgame manages all that before launching into a time travel adventure and an ultimate showdown that pays off the 21 Marvel films that came before over the past 11 years. I’m sure it doesn’t make sense at all as a standalone, but for fans of these movies it was a satisfying conclusion to this era of the MCU, filled with humor and heart.

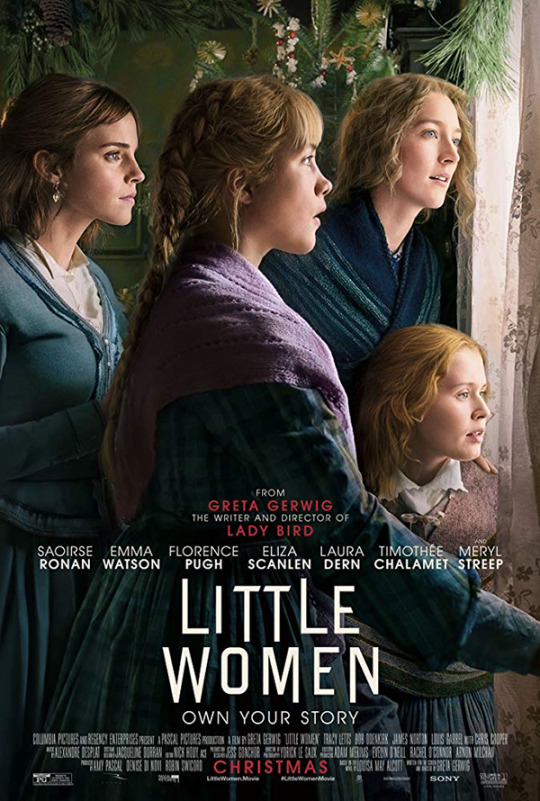

3. Little Women

I have no connection to the source material at all, having never read Louisa May Alcott’s book or seen any other screen adaptation, so I cannot compare it to anything that’s come before. I can say Greta Gerwig’s follow-up to Lady Bird is simply fantastic, with an engaging cast and beautiful cinematography that radiates warmth. I’ve read that the novel’s chronology is linear and this movie rearranges it with flashbacks, creating juxtapositions that reveal a great deal about characters, choices and the passage of time. It all leads to a somewhat meta finale that serves as a salute to the creative voice.

2. Ad Astra

As with the likes of Gravity and First Man in recent years, James Gray’s Ad Astra recognizes that traveling to our inner spaces is as transformative as venturing to the stars. Set in a near future where the moon is a rundown spaceport and Mars has been colonized, Brad Pitt plays an astronaut tasked with finding out what happened to his father’s missing mission to Neptune decades earlier. Atop a fascinating backdrop of space futurism, the film is a meditation on the loneliness and isolation of space and the meaningfulness of community and connection.

1. Knives Out

This relentlessly entertaining murder mystery from Rian Johnson (The Brothers Bloom, The Last Jedi) not only satisfies from a plot and character perspective, but delivers a level of social commentary and critique of white privilege akin to Get Out without feeling didactic about it. The cast is terrific all-around, but Daniel Craig’s starring turn as thickly drawling Detective Benoit Blanc is note-perfect, especially as he chews his way through Johnson’s hilariously meaty dialogue.

Bonus! Honorable Mentions:

Apollo 11 – Comprised of newly discovered and restored NASA footage of the first moon landing, this fresh and immediate documentary brings history to vivid life without leaning on talking heads or narration. (View alongside last year’s Neil Armstrong biopic First Man for an even richer experience.)

Spider-Man: Far From Home and Captain Marvel – two more solid additions to the MCU that are honestly probably in my Top 10, but it seemed excessive to give 3 slots to Marvel and Endgame was the clear standout. That said, Gyllenhall’s performance as Mysterio was all types of fun (see also: his gleefully unhinged turn as “Mr. Music” in Netflix’s John Mulaney & The Sack Lunch Bunch special) in the former and directors Bowden and Fleck bring warmth and humanity to a great buddy comedy in the latter.

A Hidden Life – Terrance Mallick’s best work since Tree Of Life tells the true story of a rural Austrian farmer who refuses to swear a loyalty oath to Hitler and is arrested for treason. The three-hour run time could have probably been trimmed but its thought-provoking meditations on resistance and conscience get under your skin.

Klaus – A Netflix original that presents an origin story for the legend of Santa Claus sounded a bit rote to me, but its story contains surprising emotional weight (that honestly brought me to tears a few times) and it’s gorgeously animated in a style that finds a groundbreaking medium between 2D and 3D.

0 notes

Text

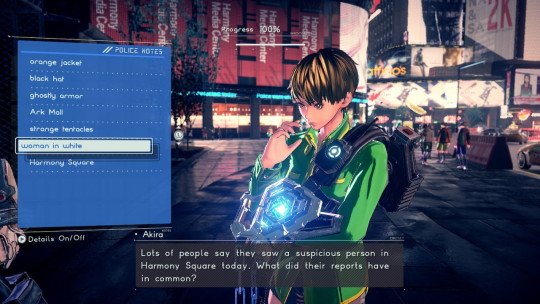

Astral Chain Review - Anime Police Academy

New Post has been published on https://gamerszone.tn/astral-chain-review-anime-police-academy/

Astral Chain Review - Anime Police Academy

Seeing Astral Chain in motion may be what catches your eye, but the graceful execution of attacks is something you have to experience for yourself. Astral Chain delivers gratifying, kinetic, and inventive combat that goes beyond genre conventions–and it retains that excitement from start to finish. Couple that with an attractive art style brought to life through fluid animation and cinematic-style cuts in battle and you have yet another standout action experience from developer Platinum Games.

As an elite cop on the Neuron special task force, it’s your job to investigate the ever-growing presence of the otherworldly Chimera that threaten the world. Catastrophic incidents are abound as Chimera spill in from an alternate dimension, the astral plane, but of course there’s more to the phenomenon than meets the eye. To get to the bottom of it all, you simultaneously control both your player-character and a Legion, a separate entity with its own attacks and abilities–think of it as a Stand from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. This dynamic is at the heart of Astral Chain’s combat.

Astral Chain’s sense of style bursts at the seams with each battle.

It takes time to get the hang of it, but once you do, working in tandem with a roster of Legions feels seamless. You earn Legions over time, accruing a total of five, and each one offers their own set of skills and cooldown attacks to upgrade via a skill tree. While they can be sent into the fray to perform auto-attacks, swapping between them effectively to juggle specific abilities creates the satisfaction of tearing down the monstrous Chimeras.

Initially, there are so many variables at play that it can be daunting. You have chain binds to lock enemies down for a few seconds, timing-based sync attacks that unleash devastating blows, and showstopping sync finishers that top off the wild spectacle (and replenish your health to boot). You can even get creative with combos, like utilizing the AOE stun, gravity pull, and crash bomb–all from different Legions–to concentrate a ton of damage on. Even an unchained combo lets you briefly unleash two Legions at once. And if that already seems like a lot to handle, you’ll also have to consider executing special attacks from directional inputs when it’s best to use them.

When you dig deeper into Astral Chain’s systems, you see some of its lineage–particularly the chip system of Nier: Automata, the game which Astral Chain director Takahisa Taura was lead designer on. That system manifests as Ability Codes that you equip on each of your Legions to grant them specific buffs and perks, which can significantly change how they function.

Astral Chain isn’t about running head-first into fights against monsters that seek to destroy you, though. You have to be smart about positioning, dodging, and the limited energy of your Legion. Enemies are more than just fodder; they can overwhelm you with sheer numbers, size, or speed. Some may require you to meet certain conditions to defeat them, forcing you to use non-combat abilities in the midst of the chaos. And bosses come at you with unforgiving attacks that’ll test your skill as much as your patience.

You have options for creating your own cool anime cop, it’s too bad they never really talk.

With a multitude of factors and challenges at play, combat places much more emphasis on devising the right tactics for the right situation. Astral Chain provides a tremendous box of tools that are effective in their own right and an absolute joy to use.

If there’s a fault gameplay-wise, it’s that movement can sometimes feel imprecise–don’t expect the same buttery smoothness of Bayonetta. For example, the Beast Legion’s mount mode winds up in an unpredictable direction, and the pistol combo forces you to flip backward. It may result in falling off ledges or unintentionally getting in harm’s way. Thankfully, it’s an occasional frustration that doesn’t detract from the core experience.

Astral Chain delivers gratifying, kinetic, and inventive combat that goes beyond genre conventions–and it retains that excitement from start to finish.

If you watch gameplay carefully, you quickly see how slow-motion, camera cuts, and subtle audio-visual cues in combat serve to signify opportune times to make your move. These flourishes are also how the game cements its bold sense of style. Popular manga artist Masakazu Katsura lent his hand to lead the character designs, resulting in some of the best-looking anime cops around. And when your bombastic actions in battle are matched by visually-striking momentum and tenacity, it delivers a unique thrill that makes Astral Chain special to see in motion.

Further complementing the game’s grand spectacle is its soundtrack. The groovy house tune heard in the police headquarters is infectious and the somber guitar melody at the stray cat safehouse hits like a reprieve from the chaos that envelops the world. Tense instrumentals and hard-hitting rock remixes of songs seamlessly bounce between one another during some combat missions. Unrelenting metal tracks propel boss battles and an ethereal Nier-like theme plays in the astral plane. Sprinkle in some J-rock worthy of an anime OP and Astral Chain rounds out the musical spectrum to great effect.

Astral Chain isn’t just about flashiness and stylish action, though. You’re given room to breathe between combat scenarios that comprise its chapters (or Files, as they’re called). Structurally, it’s somewhere between the traditional open world of Nier: Automata and segmented stages of Bayonetta–chapters funnel you through hub areas where you’re free to take part in side missions or explore for optional activities. Not everything is laid out on your map, so it takes some detective work to unveil all the hidden content.

Astral Chain’s shortcomings don’t overshadow what it does best. It’s an incredible execution of a fresh take on Platinum Games’ foundation, standing among the stylish-action greats.

Investigation scenarios are peppered within the main missions, where you analyze the environment and talk to locals to solve the mysteries at hand. Piecing the clues together properly awards you with a top rank, and it’s no sweat if you get things wrong. You’ll often jump into segments of the astral plane, which feature the more intense fights, and these areas incorporate light puzzle/platforming elements that ask you to use Legion powers in different ways.

The activities you undertake outside of combat aren’t exactly groundbreaking, but they provide enjoyable ways to engage with Astral Chain’s vivid world. It’s a welcome variety that also helps the pacing from chapter to chapter. Astral Chain never sits on one particular element for too long; it knows when to move on.

Investigation is just one way Astral Chain breaks up the pace.

Now, style doesn’t always equal substance. The overarching plot touches on the conventions of evil authority figures who abuse the power of science for their own agendas, and it also relates to the nature of how you’re able to wield the power of Legions, which are tamed Chimera. However, these themes are hardly explored. Rather, Astral Chain relies on cliches within its story and exposition. As a result, the more pivotal moments feel a bit less consequential. While some anime-esque tropes are just plain fun to see play out, others are borderline nonsensical even in context.

While you choose to play as a customized male or female cop on a special task force, your sibling–who’s on the same team–becomes the narrative focal point with fully voiced dialogue. Your own character is relegated to being an awkward silent protagonist. It’s disappointing because Astral Chain has so much stylistic potential to build from in order to give its lead character a distinct attitude. I can’t help but see it as a missed opportunity, especially when both characters are voiced when they’re your partner. In the end, the narrative presents stakes that are just high enough that you’ll want to see it to the end, and, thankfully, every other part of the game remains outstanding.

Astral Chain’s shortcomings don’t overshadow what it does best. It’s an incredible execution of a fresh take on Platinum Games’ foundation, standing among the stylish-action greats. And its own anime-inspired swagger makes fights all the more exhilarating. You’ll come to appreciate the calmer moments in between that add variety and offer a second to relax before jumping back into the superb combat. After 40 hours with Astral Chain, I’m still eager to take on the tougher challenges, and I’ll be grinning from ear to ear as I hit all the right moves, one after the other, while watching it all unfold.

Source : Gamesport

0 notes

Text

Dystopian futures, robot wars, souped-up ultraviolent and technology-enhanced ne’er-do-wells, and a not-so-small smattering of neon lights and graffiti — Neon City Riders is a cyberpunk love-letter by indie developer Mecha Studios that aims to capture the “Nintendo-hard” feel of games of old.

I recently played the game for about six hours on the Switch, and the two things that immediately grabbed my attention were the art direction and the difficulty curve. I have always been a sucker for striking visuals, and the neon-saturated apocalypse of Neon City oozes with character. Inhabitants sport spiky mohawks, chains and baseball bats as they take on protagonist Rick, who himself wears a hockey mask and brandishes a metal pipe. He’s a pixel version of Casey Jones fighting pre-mutated Bebops and Rocksteadies. Interspersed among the humans are robots and what appear to be humanoid animals. The sprite work overall is gorgeous and vibrant and by far my favorite aspect of the game. The look of the game definitely leans heavily into the “punk” of “cyberpunk,” and it’s a bit of a nostalgia bomb for a bunch of ’80s cartoons and shows I grew up on.

It’s also gunning for the same “Nintendo-hard” feel of those games I grew up with. The game begins simply enough: Neon City is being taken over by four evil gangs, and it’s up to Rick to stop them. But first he needs to train in a virtual simulation to learn all of his abilities and gain the strength to overcome the evil baddies. Pretty standard fodder, but I don’t look for deep story when I play something like Neon City Riders. I want fun controls and engaging combat, and for the most part I got that. At least in the opening sequence. The VR world is a small slice of what the actual Neon City is like, with Rick running off in the cardinal directions to find pins that power him up. He gets a dash ability, a parry ability that took me way too long to get the hang of, a momentary invincibility, and a sort of X-ray vision that lets him travel along hidden paths or see boxes he can’t otherwise. Each one is a neat gimmick that you can mix and match into the fights with gang members or traverse the land. I was especially fond of the dash ability. Not only does it let you break through certain obstacles, it just makes moving around faster and it felt nice. Every ability uses up some of your stamina so you can’t just use them willy-nilly, but thankfully it refills quickly so you can get back into the groove without much fuss.

Then the tutorial ends and you lose all those fun gimmicks, and the game immediately slows to a painful, grinding halt. I don’t necessarily mind the “gain abilities then lose them and have to gain them back” narrative conceit, but the basic gameplay in Neon City Riders is repetitive and kind of boring, so having fun goodies only to have them taken away almost immediately was a bit of a buzzkill. I don’t think losing them would have bothered me as much if I could retrieve them within a respectable time frame, but I spent about an hour in the tutorial VR section, and the rest of my playthrough was trying to get one ability back. Even coughing up the lion’s share of time to me just not being good at this type of game, that is a bad ratio between having fun stuff to do and slogging through difficult levels with only the basics.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The vast majority of my time was spent in Audiobats turf to the north. It’s a run-down, set afire slum where gang members lackadaisically vandalize buildings with spray paint and praise their freedom to do whatever they please. They’re led by vinyl-enthusiast Grand Master Thunder whose main goal is the preservation of music from before the robot wars. In order to progress through the area, you have to rescue five captured citizens from gang dens, each filled with electric fields, energy beams, and breakaway floors. Most of these obstacles would be easy enough to traverse with your dash ability, but alas, that has been taken away and you have to make your way around them the old-fashioned way. It’s slow and tedious, and considering most of the traps are one-hit kills, it proved way more aggravating than it needed to be. Patience and pattern recognition are the name of the game here, much like those old style Nintendo games, but here it felt much less joyful and far more frustrating. The difficulty never felt unfair, and I can recognize that a good chunk of my deaths can be attributed to my lack of skill, but there’s also no real learning curve to be had. It’s sink or swim, and after having just had an enjoyable experience gaining new abilities and opening the game to more creative gameplay, being thrust back to square one but with the difficulty still ramped up to when I had my tools felt more punishing than challenging.

That being said, I was more than willing to bang my head against the game to get good, but unfortunately the aspect of Neon City Riders that I loved the most is also what made me ultimately put it down for good. The art direction is impeccable, and the game absolutely nails the look and feel of this world. But as the name implies, Neon City is, well, neon, and filled to the brim with flashing lights, high contrasts and, most pivotal, a menu system that makes heavy use of flickering. After about an hour of playing I would get horrible headaches from the flashing, and I couldn’t actually use any of the pause menus because the constant flickering made me nauseous. In its defense, the game warns you every time you load it up that it contains flickering lights. This is of course an issue specific only to me, and it will more than likely not affect most others playing the game, but it made it impossible for me to keep going.

Warning: The below video contains bright lights and excessive flickering.

http://operationrainfall.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Neon-City-Riders-menu.mp4

I liked the world of Neon City Riders. The music is great and reminds me of the SNES Shadowrun‘s banging soundtrack. The look of the game is impressive, and I loved that the city itself isn’t only filled with bad guys. You can pick up quests from the residents, and there is a bunch of freedom of exploration. I’m a lore hound, and this game oozed world building from its pores. The writing is light-hearted and fourth wall breaking, which I can always get behind. Running around the world and exploring its nooks and crannies was legitimately a good time, and the fights with goons were fun when you picked up on their attack patterns. Finding a rhythm while fighting a group was the best part of the combat after losing all my goodies. Getting those goodies back, though, made the game feel like a slog at times, and the one-hit deaths began to wear thin. For people who like a challenge and appreciate old-school sci-fi and grunge, I think this could be a fun romp. Just be aware that the game has a steep learning curve, and unfortunately just was not a good fit for me.

Neon City Riders is available for the Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Steam at $19.99 USD.

youtube

IMPRESSIONS: Neon City Riders Dystopian futures, robot wars, souped-up ultraviolent and technology-enhanced ne'er-do-wells, and a not-so-small smattering of neon lights and graffiti -- …

0 notes

Text

Book Review: My Cross To Bear by Gregg Allman With Alan Light

By: Arlene R. Weiss Photos: Courtesy William Morrow

When it was announced that the legendary Gregg Allman, singer, songwriter, keyboardist, and guitarist of one of music’s most influential bands, the equally legendary, landmark, Allman Brothers Band, was penning his personal memoirs, I very much looked forward to reading the autobiography of one of music’s most gifted and iconic artists. And upon reading Allman’s tremendous document, My Cross To Bear, what a thoroughly compelling, riveting, and wonderfully enjoyable book it is.

After considering several titles, Allman settled on aptly titling his life chronicle after the song, “It’s Not My Cross To Bear”, which he wrote for the Allman Brothers Band’s 1969 debut album. Only for the book’s abridged adaptation version, “My Cross To Bear” of Allman’s song title, it more than references the heavy load of life, endured by this world weary musical road warrior’s inspiring life odyssey.

Just as many of the countless, stunning songs that Allman has composed throughout his storied life have been deeply personal, resolute, and autobiographical, Allman’s memoirs lay bare his innermost soul. He speaks of his long struggle with, many rehab attempts at and ultimately successful sobriety over, years of self destructive drug and alcohol abuse. The book covers its ravages on his health, (culminating in Allman’s successful liver transplant in 2010), decades of turmoil, feuds, dissolution and reconciliations within the Allman Brothers Band. He opens up with loving memories and recollections of the heart involving the unforgettable people whose lives most touched his, with Gregg’s deepest reverence and love for his late older brother, legendary slide guitarist Duane Allman.

In a January 2002 interview with me, Gregg related that, “Well, they say you don’t have to have the blues to sing the blues, but it helps if you know what they are….if you had them before. And I have gone through one whole lot….two, three, lifetimes of fun and maybe one and a half of struggle and pain, or at least my share, let’s put it that way. I’ve been through my share of trouble and woe. I’m not unfamiliar to it, that’s for sure.”

No stranger to a life crossed by the seemingly unstoppable onslaught of the lowest of valleys, but also the highest of mountain tops, plagued at times by tragic events and personal and professional hardships, Allman transcends all through his steadfast perseverance, resilience, redemption, and triumphs. Allman’s new book is deeply confessional and introspective, painfully brutal, emotionally wrenching and powerfully cathartic, reflecting the intense pain and many scars that he’s accumulated in his turbulent life.

Yet, Allman’s comprehensive life story is also imbued with deeply fulfilling, touching, poignant, and emotionally uplifting personal and professional relationships, inspirational creativity and artistry, and endless rewards of the heart, that have shaped and informed his music, his career, and his life.

Throughout Allman’s moving and insightful narrative, he speaks with equal moments of reflective candor, wistful and pensive melancholy, and exuberant joy for the long, creative life journey that he has experienced.

Unlike many of the recent bitter and caustic, tell all, autobiographies of rockers Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, and Motley Crue, Allman’s book while still exploring the plaintive darkness that has often shaded his life, is also a surprisingly sweet, warmly humored, and deeply affectionate personal document that is just beautifully written.

Allman recounts and often regales with great exuberance and wistful joy, his and Duane’s childhood, their musical beginnings, and earliest musical experiences. He tells about honing their musical chops, starting from their high school dances, then touring cross country as the Allman Joys and The Hourglass, to Duane’s tenure with the 31st February, to Gregg being forced to stay in L.A. and fulfill his contract with Liberty Records. He reflects on the moment when getting that infamous life changing phone call from Duane who was living back east in Jacksonville, Florida, to come join what would evolve into the seminal, Allman Brothers Band.

After Duane’s and bassist Berry Oakley’s tragic and untimely passings, Gregg discusses how he pondered whether or not the band should soldier on. Thankfully, and all the better for us, the phenomenal, “Brothers Of The Road” realized how much they loved making and playing music.

Allman also generously peppers his book with tremendous anecdotes that are often imbued with a sweet, warmhearted, and delightfully witty, sense of humor. One story that Gregg relates, begins with Duane’s passing, and sets in motion an affectionate, playful windup with Gregg’s tongue planted firmly in cheek as he expounds with seriousness to his readers, that after Duane died, people only remember and spoke of the good things about Duane – to which Gregg then brings up that there were indeed “shi* parts to my brother as well”. Then as you fully expect Gregg to spill some shocking evils about Duane, Gregg proceeds to kiddingly and fondly accuse Duane of committing the ultimate crime of waking up in the morning with bed head hair…and there’s much more about Duane where that exuberantly fond whimsy came from, regaled throughout the book from Duane’s little “baybrah” Gregg, [Duane’s affectionate nickname for his baby brother].

Gregg’s spot on droll opinions of The Grateful Dead, and especially, his deadpan delivery observations recounting how playing the guitar changed him from being a budding virgin into becoming a mature man of pleasure, are beyond priceless. “Girls had never noticed me until I bought a guitar, and for a while I thought, “Well, is it because I play music? What if I sold insurance?”

My favorite story, and Allman’s good natured wit is indeed in rare form here, iswhen he recounts his hilarious experiences during his solo band’s tour of Europe in the late 70’s accompanied by his then wife Cher, with who he had just also recorded and released their 1977 duet album, “Two The Hard Way”. Both Gregg and Cher each had their own unique camp of just slightly overly zealous fans and when the two singers performed onstage together, things got a little messy between the two fan bases who didn’t quite mix well together, to say the least.

But, it is Allman’s remarkable gifts as a storyteller, when imparting the most unforgettable and meaningful cornerstone moments that have strengthened his purposeful resolve, and that have defined his career and life, that truly make Allman’s life and book so moving. He reveals, despite the immense adversity he has known, ultimately, that his life has indeed been very worthwhile, joyous, and uplifting.

Moments that stand out in Allman’s reflections. Gregg’s immense sense of family, as he and Duane forged an unbreakable childhood bond in military school, while their widowed mother pursued a CPA license and degree to care for her sons. That bond carried through to their adult years and beyond Duane’s untimely death, continually inspiring Gregg, serving to guide and propel him onward, even as he often has faced the firestorm of life.

Then there’s Allman’s wondrous stories expounding the spark that first inspired Gregg and Duane to learn to play guitar and the genesis of how these two burgeoning guitar playing brothers from Nashville went on to become two of music’s most consummate music artists.

Gregg proudly relates his somewhat unconventional relationships and utter devotion to all of his children. It seems that music runs deep and rich in the Allman family, with next generation musicians Devon Allman of the band Honeytribe, Elijah Blue, his son with Cher of the band Deadsy, and rock singer Layla Brooklyn of the band , Picture Me Broken.

There’s Duane’s first time learning to play slide guitar, with a Coricidin cold pill bottle, playing along to a Taj Mahal recording of “Statesboro Blues”. Gregg writing the elegiac “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” on a 110 year old Steinway Piano and many more glittering jewels from Allman’s spellbinding memories.

Most of all there is Gregg discussing how he first became a singer, how he learned how to sing the blues, and how he wrote, what was the inspiration for, and the immense stories behind, his exquisite and sublime songwriting repertiore, both with The Allman Brothers Band, and also his supreme artistry as an amazing solo artist. How, Gregg composed, what has become his signature song, the sublime “Melissa”, and how he at last came up with the song’s title. From the blistering “Whipping Post”, to the hope filled “Oceans Awash The Gunwale” to the iconic, transcendent “Dreams”, to the song that you’ll be happy to find out is the song that Allman is most proud of composing….but you’ll have to read the book to find that one out.

Allman’s ruminations also include much of the headline grabbing tabloid fodder that has plagued the Allman Brothers Band for over four decades, from recounting the infamous Scooter Herring debacle to relating his years of dealing with internal band friction from contentious former Allman Brothers Band guitarist Dickey Betts.

However, for those very familiar with and knowledgeable of Allman’s life, music, and career, his recollections display remarkable restraint and refreshingly reserved tact to many of the people who have passed through his life, in particular to many of the “multi-colored ladies” in his life.

Allman is especially reverential to ex-wife, pop singer and Academy Award® winning actress Cher. He seems to have developed a downright revisionist and extraordinary regard, respect, and affection for her after all these years. While fondly relating, that of his six ex-wives, Cher is the only one that he maintains a friendly relationship with.

Allman also carefully chooses his battles and his words. Though readers may be left unsatiated at Allman’s reigning back and abstaining discussing some of the insider details chronicling certain agrievous music industry personages and business dealings that have been part of the Allman Brothers Band’s career – Longtime, former tour manager, band archivist, tour manager Kirk West isn’t mentioned at all – Former ABB Manager Danny Goldberg gets little more than a namecheck – Though Allman expresses his well known disdain for the band’s undeservedly maligned two albums for Arista Records, the pop confectioned 1980’s “Reach For The Sky” and 1981’s “Brothers Of The Road”, helmed under the auspices of Arista President Clive Davis, Davis is also noticeably, completely absent from the book.

At the same time, Allman recounts in great detail, his and Duane’s trials and tribulations recording and touring within the constraints of Liberty Records in their Allman Joys/Hourglass Days. And Allman pulls no punches in recounting the gory details of many of the music business people who he feels dropped the ball with either his solo career (former manager Alex Hodges) or with The Allman Brothers Band. He recounts the career highs and lows of the late Phil Walden, founder of Capricorn Records who originally signed and managed Duane, and then later, the Allman Brothers Band to Walden’s pioneering record label, only to lose Capricorn, it’s entire artist roster, and the ABB, via his shady financial “chicanery”, which also included conniving Gregg out of all of his songwriting publishing rights at the time.