#ooduaculture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When the crocodile was coming to earth from heaven according to Ogbe Yonu

Olodunmare asked the crocodile how did you want to live on earth who did you want to be on earth. Did you want to live amid easiness but have a meaningless life or did you want to live amid enemies and have a life called legacy? The crocodile told Olodunmare please give me some time so I can think about it. The crocodile then went and made ifa consultation with Orunmila who told him to make sacrifices and remove fear away from his heart and the crocodile. He was asked to offer sharp objects like blades, knives, and pins. After he finished making the sacrifices the crocodile went to sleep and went to Olodunmare the next day. The crocodile told Olodunmare please I want the life of Legacy and then Olodunmare put his Ase on his request and he was sent to earth. On getting to earth the crocodile couldn’t live among humans and other animals on the ground because they wanted his meat and he was so different … also he couldn’t stay under the sea because the sharks and the whales wanted to eat him up too … He lived in fear and pain One day he remembered the Ebo he did with Orunmila and he shouted at the top of his voice … I made Ebo: why again am I suffering … why again am I in pain … why am I not living in peace? Orunmila replied : Ebo doesn’t mean that your destiny would not happen. it would only beautify it Ebo doesn’t mean that you would not have enemies. It would only make you conquer them Crocodile do not fear cause you have been blessed with two features … you will live on land among the animals and you will live in the water among the fishes and the sharks of the sea and they will be able to do nothing to you. Ooni waka-waka baba re lo ni bu … Kosi eni tii yoo gba odo lowo Ooni From that moment onward the sharp object that the crocodile used in making Ebo came out of all his body and whenever an animal whether in the sea or on earth tried to hurt him. They are always cut and they end up injuring themselves till now his Ebo has stood up for him. Your destiny is the reason why things that are easy for others are hard for you … your destiny is the reason why you felt so down and unable … You choose this life yourself … Don’t be scared to live it whenever you think you have a problem think about the crocodile that couldn’t live on the ground and in water for years but ended up ruling it. Whenever your enemies … Backbiters and haters never want you to be in. You shall be there and rule over them Ase O!!! Ajagunmale Alaajeifa Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

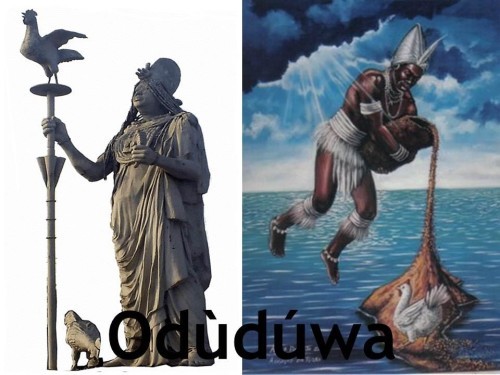

In Oodualand (Yorubaland), money has never been foremost in the Oduduwa (Yoruba) value system

In our value system money is number six What are the first five you may ask? - The first is làákà’yè - The application of knowledge, wisdom & understanding… (Ogbón and ìmò òye) - The second is Ìwà Omolúàbí - (integrity) Someone with integrity is a man/woman of their word. If you have all the wealth in the world but lack integrity, you are not worth a thing. Integrity is combined with iwa, (character) which we regard as Omolúàbí. - The third is Akínkanjú or Akin - (Valour). That is why Balóguns is second-in-command to the leaders in Oodua land (Yoruba land) Balóguns are people that can lead them to war. To lead with great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. Oodua (Yoruba) people have no respect for cowards. - The fourth is Anísélápá tí kìíse òle - (Having a visible means of livelihood). A person must be identified with a visible means of livelihood that guarantees a lawful income or sustenance. His or her profession or job must be open and legally approved by society, and not through cheating or forcefulness. - The fifth is iyi - (Honour) Oduduwa (Yoruba) people place a premium on the gait with which individuals carry themselves and their public reputation. That is why Oodua or Oduduwa (Yorùbá) people usually say when you set out to look for money and you meet honour on the way then you don't need the journey anymore, because if you get the money, you will still use it to buy honour. - The last in the Oodua (Yorùbá) value system is owó tàbí orò - (Money or wealth). If putting money ahead of the other five, then you are nobody in the Yoruba land of the olden days. Unfortunately, this is being pushed to the front burner nowadays due to the erosion of our value system. Please feel free to share with fellow Yoruba sons and daughters Read the full article

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Phases Of Every One of Us

In Oodua (Yoruba) Mythology, there are three phases that each of us individually must pass through. It’s important to also note that we’ve been existing even before we were born and death is not the end. Egbé The first phase is before we were born, we were among other fellows Elegbe in Òrun. It’s the life that we live over there that prepares us and determines the kinda life we will have here on earth. The process of going to Àjàlámòpín to plead and request for a good Ori. Also using our mouths to choose our destiny and state how we want our lives to be. To the process of going to meet our Egbe to inform them of our purpose of going to earth, the duration of time we are going for and the purpose. Also to Àyànmó which is what is chosen for us. Then to the last process of going to embrace the tree of forgetfulness. All of the above are part of what determines what our life looks like. Born and Alive It’s important to note that we’ve been living even before we were born. Being conceived is the beginning of the next phase and the continuation of the past life you were living. Our existence on earth is a race to fulfill our destiny, live a life of fulfillment, go through the good and the bad, and connect with the divinities for spiritual elevation. The end of this particular phase is DEATH! Ancestor To die now is to die no more. Dying is the journey toward becoming an ancestor. We came from Egbe to become Ènìyàn and later end up becoming an ancestor. Not everybody ends up becoming an ancestor. Some couldn’t fulfill the purpose before dying and they return to Egbe for them to be reborn while some reincarnate. To become an ancestor is to become an Orisa. You watch over your loved ones, bless them, protect them and sometimes communicate with them while they venerate you in return. So you see, in Yoruba belief, life is a circle and at the end of the day, you are returning to where you started. From Egbe to Eniyan, then to Egúngún(Ancestor) and the circle goes on and on and on. Àború Àboyè! Pópóolá Owomide Ifágbénúsolá Read the full article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

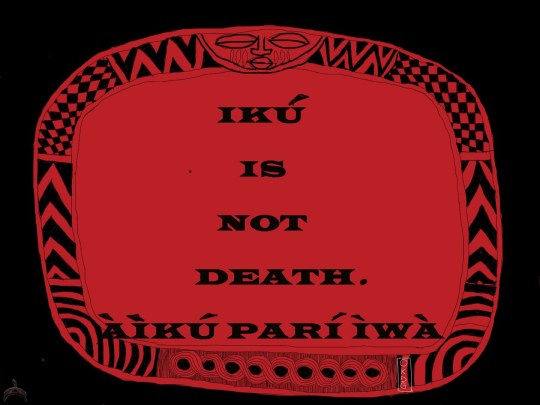

Iku

Ikú, conventionally translated as death, is in fact not "death." Iku is the vehicle of ÌPAPÒDÀ, or transition to Ọ̀run, the source of all being. We must all make this transition, because AYÉ LỌJÀ, ỌRUN NILÉ. To experience Ikú is not to die. It is to move on to the next level. 'Death is not final. It is a change of location from the physical to the spiritual'. Prof. Moyo Okediji Read the full article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

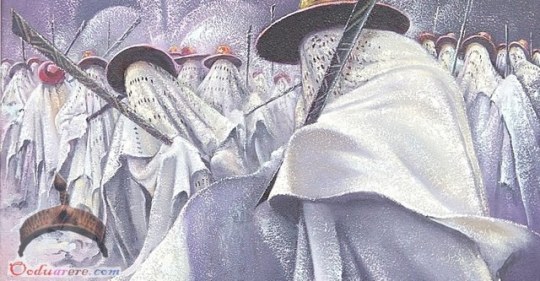

Opabata - A Week-long Agògòrò Èyò Festival

The Eyo festival, also known as Adamu Orisa, is a communal event, a week long Opabata show enacted so that the Orisa Adamu may welcome the recently departed into the spirit world. The appointed head of the festival is the Adamu Orisa, usually a high-ranking or respected figure, who opens the festival with a white pigeon in his hand and journeys around Lagos throughout the celebrations. Festivities take place throughout the city with citizens from all strata of a society celebrating in a spirit of camaraderie. Food and drink are dispensed to all and old disputes are settled. An important feature of the festival is the homage to the king, the Oba of Lagos. However, the festival’s most visible attribute is the Eyo masquerade dancers, disguised in flowing white gowns and veils surmounted with large straw hats. The dancers perform to a retinue of drummers while wielding large ceremonial sticks called opabata.

The eyo masquerades outfit is not complete without the special staff (opabata) which is held across the chest by both hands through the dance processions.

The festival was first staged in 1854 in honour of the late Oba Akitoye of Lagos and since then, it has remained a prominent festival, which seeks to celebrate the life and times of prominent, but, dead Lagosians. A complete paraphernalia of Eyo consists of a white flowing gown that covers the head and feet which symbolises the spirit.

The Eyo wears a headgear called Aga, with each group having separate colours for its Eyo. Eyo usually carries a long palm stick called Opabata as his staff officer. The stick is, usually, with artistic inscriptions to express its uniqueness and beauty. Opabata is normally used by Eyo to greet each other and elders. They also use them in beating offenders or harassing their friends. The different natures, colours, and costumes of the Aga distinguish the chiefs, their groups, and Eyo. The groups include Adimu, Oniko, Okolaba, Ologede, and Agere. While there are royal Eyo like Olorogun, Aromire, Oloto, Bajulaye, Akitoye, Eletu-Odibo, Onilegbale, Onitana, Ogunmode, Onisemo, Ashogun, Oluwa, Jakande, Eti and Ashodi among others. Each Eyo is easily identified by the nature of his Aga.

Preparations for the grand procession of the Eyo festival are rooted in long-standing tradition and no one dares alter the sequence or denigrate it. From the chosen date to the inscriptions and demarcations on the staff, from which each family erects the Para, to who has the exclusive rights to dismantle it, from costume to public conduct when in uniform, every single detail is closely observed and strictly adhered to.

There is a week-long Opabata show, with the Agbodo dance and rituals to be performed by Chief Eletu-Odibo, this marks the beginning of the festival. The major music of the show is Korogun, consisting of Iya- Ilu, two Omele drums, Konkolo, and gong. Drumming and other musical equipment accompany the Eyo as they move around the streets of Lagos during the festival which involves thorough merry-making.

Regulations & Significance However, there are basic regulations to be adhered to by the public during the Adamu Orisa festival on sighting an Eyo. First, everybody must remove their shoes, head-ties, and caps, women must not plait their hair (Suku style), umbrellas must be folded, riders must dismount from bicycles and all cigarettes and pipes should be put away. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

'Gangs of Lagos' - Unjust profiling of a people and culture as being barbaric and nefarious - Lagos State Government

The Lagos State Government has released a press statement accusing promoters of the movie ‘Gangs of Lagos' of marketing a mockery of the heritage of Lagos. The statement posted on their state government's official website reads: “Lagos State Government has expressed displeasure with the promoters of the “Gangs of Lagos” film/series over cultural misrepresentation and for portraying the culture of Lagos State in a derogatory manner. We recall several of these kinds of direct attacks on our traditions and immense campaigns to distort history and generate facts. The use of media such as Nollywood, Netflix, and Prime Video to constantly downgrade, and embarrass the spiritual representation of the people. One such is libeling Esu as satan at every chance given in any of the script writers and interpreters despite a lot of awareness being brought to the limelight about the distortion of history which has since forced google translate to change this negative connotation, a massive psychological attack just for the simple reason of hating ourselves and everything we hold dear.

Gangs of Lagos

Gangs of Lagos is one too many of such libel against the tradition of the people the government should not only speak against but also lay the standard for these scriptwriters to follow. “A release signed by the Commissioner for Tourism, Arts, and Culture, Pharm. (Mrs.) Uzamat Akinbile-Yussuf said the Ministry, being the regulatory body and custodian of the culture of Lagos State, views the film/series as a mockery of the Heritage of Lagos. “The Commissioner expressed her disappointment with the promoters of the film, Jade Osiberu, and Kemi Akindoju, for portraying the Eyo Masquerade as a gun-wielding villain while adorning the full traditional regalia.” According to the statement, Uzamat Akinbile-Yussuf said: “We are of the opinion that the production of the film ‘The Gang of Lagos’ is very unprofessional and misleading while its content is derogatory of our culture, with the intention to desecrate the revered heritage of the people of Lagos. It is an unjust profiling of a people and culture as being barbaric and nefarious. It depicts a gang of murderers rampaging across the State”. Akinbile-Yussuf maintained that the Adamu Orisha, popularly known as the Eyo Festival, is rarely observed and only comes up as a traditional rite of passage for Obas, revered Chiefs, and eminent Lagosians. She added that the Eyo Masquerade is equally used as a symbol of honour for remarkable historical events. It signifies a sweeping renewal, a purification ritual to usher in a new beginning, a beckoning of new light, acknowledging the blessings of the ancestors of Lagosians. The statement by the Lagos State Government has been widely condemned by Nigerians on Twitter. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

My Best Enemy: Part 3

Fear gradually gripped me, as I sat there in the hot shop with my father, my mother, and other relatives, waiting for a crowd of assorted characters gathered in front of the shop to set us ablaze. I was not thinking. Rather, several things were dashing through my mind. What would it feel like to be set on fire? Miraculously, I was no longer hungry. I controlled the motion to throw up as it welled up my stomach. Several of the characters standing outside the shop, looking perplexed, excited, and anxious caught my attention briefly. Vividly, I recalled them, their anxiety, their anticipation, their helplessness, and their cluelessness about what was happening around them. Just like me, spectators in our lives, waiting for them to make the next move. There was Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn. The bamboo pole wearing a gown. What a sexist mentality fed my childhood concept of being human. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn, this sheer bamboo pole that dared to wear a gown was the most gorgeous young woman of about sixteen. At that age, I consumed imageries largely through sound and not what I had experienced. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn was blooming and her entire being radiated light, energy, purity, and sheer spiritual fermentation. There was a wave of Ankara fashion in vogue at that time, and Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn was always adorned in brilliantly colored attires, sporting a tiny dress cut tight and up above the knees. The style was common among our sisters at that time. There were three stereotypes of our sisters at play on our streets: we called them illiterates, half-educated, and over-educated, none of which was good. We had street eyes for telling one from the other. The first category consisted of the indigenous ìbílẹ̀ sisters, almost no “education,” because we were raised to think in those days that only those who went to western or “formal” schools were educated. The secondary category is the one to which Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn belongs. She has read up to Primary School class six, where free education ended in those days. Her parents would now be expected to fund her education, once she completed her primary six education. The Awolowo government had brought free formal education up to the first six years of Western Nigeria, and every child, boy or girl in the neighborhood, was expected to attend school. Almost every child, except the Ọmọ Ọ̀dọ̀—about whom we will talk some other day. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn was the first generation of her family to experience formal education. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn grew up first in a loosely defined family when the concepts of monogamy and polygamy were developing complications of colonial western morality, religion, and politics. The west was changing us dramatically and drastically. A culture of educated elites was emerging, but not for Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn, whose education stopped at the Primary six levels. The last level of education you needed at that point was the Modern Three certificate, to teach at the primary school level. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn was educated below Modern Three. You couldn’t do much with that. People like Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn were caught between two classes; the lowest level referred to as illiterates were connected to the land, farming, and the indigenous markets. The over-educated ladies had a connection. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn’s prospects were limited. She must get married as soon as she could, otherwise, there would be too many stories made up told about her in the neighborhood. In those days, fiction writing was an active sport on the street, except it was an oral tradition passed from ear to ear. There were no television, movies, or video games to play on the phone. All we had to watch was the big screen on the street. Nobody was too stupid to point their fingers at anybody. You learned by age three how to point at people using only your mouth, the way you slightly twist it. Or your eyes; your nose. You learned to turn your back to the subject of your gossip. As long as the streets existed, the ladies were the stars of the movies and Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn and her friends were spotlights. She would be given too many names, such as Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn. Nobody would know her real name. Everybody would call her Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn. I remember the day I was greeting her, just drawn to her by the radiance of her aura, and I hailed, “Anti Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn, how are you doing!” As a four-year-old, I felt that adding “antí” to her name was all I needed to do. Probably it was the flowery patterns on her gown, I can’t tell. But something compelled me to greet her. But she snapped back with “Can you call your own sister Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn?” That was the first time I was called out so publicly. Clearly, I said something wrong. But Anti Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn looked so upset with me that I could not ask her to explain anything to me. Best to crawl away home. It was a culture in which you were supposed to know things from home: things weren’t supposed to be explained to you on the street. So when I got home, I was really upset and asked everybody why nobody told me it was offensive to call Anti Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn by her name. “Don’t tell me you called her—what!!!?” Everybody gathered around me. “So, what did she do to you?” one of my sistas wanted to know. Only Olodumare knew how many sistas I had in those days. They would all crowd around my head. “Did she kill you?” someone asked. “If you had any brain between your ears,” someone said, “something should have told you that---” “If they asked you to poke your fingers into a burning stove,” someone asked, “would you have done that?” I learned my lesson the hard way about Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn, but I didn’t fully get it until my mother explained things to me. It was offensive to call someone Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn because it was not kind to use images like that for people. Young women like Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn got all sorts of socially undesirable names such as asewo, public dog, anfani adugbo, kofoorun, thrown at them by frustrated young men in the community, my mother explained. I was to be careful not to call people those names, my mother instructed me. As a child of about four, I didn’t factually know anything about Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn, yet I had been led to view her as an outsider already. Perhaps I saw Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn as an outsider because I realized that my formal education was not going to terminate at the primary school level and that I had more opportunities. Young women like Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn were in big trouble. Many parents did not consider sending their female children such as Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn to school beyond the free primary education. They didn’t see it as worthwhile, because the girl was going away to become someone else’s wife. But a lot of people were also taking advantage of the opportunities of formal education and were sending boys and girls to school. Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn saw me as I stepped out of the school compound that day. “Come, quick, Moyo!” she said to me, whispering. “Duck, don’t let them see you! Come and hide inside our house!” I didn’t know what she was saying. I thought maybe she was still upset that I called her Anti Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn. I walked straight past her. I wanted to run home away from her. When I turned the corner to the main street, I met the restive crowd gathered in front of my mother’s shop. It was while I was pushed into the shop, and looked around me at my mother, father and relatives also trapped within the shop that the story was becoming clear to me. I began to understand what Ọparun-ń-wọ-gáùn was trying to do. She was trying to save my life. She was my Valentine. I completed painting her on Valentine's Day.

Prof.Moyo Okediji Read the full article

0 notes

Text

My Best Enemy: Part 2

“I remember so very clearly when hooligans came to burn down your mother’s shop,” Aduke said. “It’s one of the most vivid memories that I carry from my childhood. I had seen you in school that same day, I think. I’m not sure of the exact date any longer.” “That fateful day is also vivid in my mind,” I replied. “You looked so confused and helpless that day,” she said. “I was crying when I saw the look on your face and the other members of your family.” “Interesting,” I said. “I had no idea anybody was watching us. It was in the afternoon. Most likely in 1963.” A large crowd gathered in front of my mother’s shop that afternoon as I returned home from school. I was hungry. The connection between my family and the crowd gathered in front of our shop was unclear to me at that time. But as soon as I arrived, one of the hoodlums strutting around the front of the crowd sighted me and said, “Here’s one of the children.” “Push him into the shop and we burn everything down with the entire family,” said the one who appeared to lead the group. They pushed me into the shop. My mother, who was pregnant, I believe, was seated there, together with my father, looking worried. It was so unusual to find my father at my mother’s shop at such a time of the day. Normally he would be at home, working on his novel, play, poetry, or whatever he was writing at the moment. The routine was that at about 7 am, he dropped my mother and the rest of us off at his mother’s shop, and he returned home to work on his writing. He would return at 7 pm to take us back home. Occasionally, he was at the shop during the day with a couple of friends to drink beer or palmwine, or just see what was going on. Given the heated political situation at that time, he probably came to see what was going on and found the crisis that was developing. Operation Wẹtiẹ̀ had already erupted throughout the western part of Nigeria, following the breakdown of law and order in the House of Legislation at Ibadan. The crisis came emerged from the political disagreement in 1962 between the leader of the Action Group, Obafemi Awolowo, and the Deputy Leader, Samuel Ladoke Akintola. Awolowo wanted a consolidation of power within the West, while Akintola favored more alliances with the North, where he felt he had more sympathy. At that point, Akintola was also the Premier of the Western Region. Akintola was relieved of his position as the Deputy Leader of the Action Group in a party convention held in 1962. The next step was to have Akintola removed by the Governor of the Western Region, Oba Adesoji Aderemi. But Akintola was smarter. Using his position as the Premier and citing legal authorities, Akintola quickly had the Governor removed before the Governor could remove him as Premier. The House of legislation on Ibadan became a place of open brawling, throwing of chairs, tables, and anything that was not nailed to the floor by members of the house as they fought to take sides between Awolowo and Akintola. Members of the public were also taking sides. The Western Region was divided between the supporters of Awolowo and those of Akintola. Thugs, hoodlums and hooligans were raised by each party to harass the opponents of the other party. The court system was coopted into the struggles. There was the case of one of my mother’s landlords who was known as an Akintola supporter in Ile Ife, a city apparently more favorable toward the Awolowo group. My mom had three shops at that time, and one of the smaller shops had a landlord who was politically active. He was stunned when court officials and the police came to his house one day to arrest him for escaping from prison. The situation was that someone pretending to be him had pleaded guilty to charges of battery, assault and robbery at a local magistrate court, without his knowledge. The person who had pleaded guilty in his name was sentenced to a prison term. That unknown person has led away to prison but was allowed to leave by the prison authorities. The law enforcement officers therefore came and arrested him for escaping from prison. I remember the day they came to arrest him, with a police Land Rover Jeep. The law enforcement officers were still trying to enter his premises when word reached him that the police had come to take him away. What the police didn’t realize was that he had planned for exactly such a situation: he had an escape route at the back. I was just about 5 years old then, as I watched our landlord descend the top of the building with a secret ladder, land on top of the roof of a nearby building, and before the law enforcement officers realized what was going on, he had disappeared into the large Agboole behind the shop, narrowly escaping capture. Later, thugs came to his house to destroy the building and loot his properties. But by the time they came to burn down my mother’s shop, the political situation had deteriorated much further, as the houses of some political leaders in Ile Ife were getting burned. It was in that context that the large crowd gathered in front of my mother’s shop, and I was pushed into the shop so that they could burn down the shop with the entire members of my family. As I was just about 7 years old, I didn’t know the full details, but as I sat together with my mother, father and some other relatives in the shop, waiting for them to burn us down, I knew we were in real trouble. Aduke said, “As I watched you and the members of your family that day, I was praying for a miracle to happen. But I was not expecting any miracle, because the thugs were coming from another operation where they had burned down the house, with the owner, said to be in the wrong political party, narrowly escaping with his life into the bush, while they caught and killed his wife and one of his children. I thought it was over for you.” To be continued.

The painting shows Ojú Iná, one of the street thugs who burned down and killed political opponents. If you take a careful look you will find the disgruntled members of the community depicted on his body. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Why Change precious names to imaginary names? e.g Ifakemi - Oluwakemi, Opeifa - Ọpẹjesu...

This could be hilarious but it's a serious matter. I was educating some youngsters on the need to embrace our cherished heritage and always give respect to our Ancestors. Why change the precious names given to them by their parents to imaginary names for religious purposes? Ifakemi has become Oluwakemi Opeifa has become Ọpẹjesu Ifafunke - Oluwafunke e.t.c These names being rejected at home, Nigeria, Oòduà land are being embraced in the diaspora. The Africans abroad are changing their colonial names to Yoruba Ifa/Orisa names. Ẹni abínibí kìí wù wọ́n Ẹni ẹlẹ́ni níí yá wọn lára ~Ìrẹ́ńtẹgbè They don't cherish their own But prefer to promote foreign ideology. One of the attendees of my lecture stood up and asked, "Bàbá wá Àràbà, our family name is Ọlọ́pàádé and I am talking to my siblings to change the name because I don't understand the meaning because they didn't tell us." Suddenly, another young boy stood up and said, "Sir, I know the meaning of the name, Ọlọ́pàádé" I was happy thinking the youngster would enlighten us. I said, "please tell him". The boy said, "it means the Policeman has come". Everyone in the room including myself started to laugh. I am still laughing. I told the audience that the name ỌLỌ́PÀÁDÉ is a name from the Divinity, ÒRÌṢÀOKO. The enlightenment of the necessity to propagate Ìṣẹ̀ṣe is a task that must be done. Stay blessed. From Araba of Oworonsoki land Lagos Nigeria. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Èṣù historical records, narratives and facts of history. - #EsuIsNotSatan

We may not have this issue in our country Trinidad and Tobago but we support our brothers and sisters who may have this challenge Nigeria and the world may Esu hear our call and fix this situation. ABORU ABỌYE ÀBÓSÍSE I AM AWO AWOSANMI ADEWALE SANGODELE ATINUMO HEAD OF THE TEMPLE ILE ÌJÓSÌN ABALAYE OFUN IKA OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO ESU IS NOT SATAN ESU IS NOT SATAN ESU IS NOT SATAN ESU YOU ARE THE IMOLE THAT WE CALL UPON TO BRING BALANCE TO ALL OUR TRADITIONAL WORKS A-bá-ni-wá-ọ̀ràn-bá-ò-rí-dá: Who is He? Ẹlẹ́jẹ̀lú Ọbasìn Láarúmọ̀ Ajọ́ńgọ́lọ̀ Ọba Ọ̀dàrà Onílé Oríta Ọba nílé Kétu Ẹlẹ́gbára Ọ̀gọ Olóògùn Àjíṣà Láàlú Ògiri Òkò Láàlù Bara Ẹlẹ́jọ́ Láaróyè Ẹbọra tí jẹ́ Látọpa These are the other names that belongs to Èṣù! Now, who is Èṣù Láàlù Ẹlẹ́gbára Ọ̀gọ? Èṣù is a prominent primordial Divinity (a delegated Irúnmọlẹ̀ sent by the Olódùmarè) who descended from Ìkọ̀lé Ọ̀run, and the Chief Enforcer of natural and divine laws - he is the Deity in charge of the law enforcement and orderliness. Èṣù is so influencing, powerful, ever relevant, and ubiquitous to the extent of having every day of the whole four-day (ancient/traditional) Yorùbá week as his day of worship (Ọjọ́ Ọ̀ṣẹ̀) unlike all other Irúnmọlẹ̀s and Òrìṣàs (primordial Divinities and deified Ancestors cum Spirits); "ọjọ́ gbogbo ni ti Èṣù Ọ̀darà". This controversial cognomen; A-bá-ni-wá-ọ̀ràn-bá-ò-rí-dá (He-who-creates-problems-for-the-innocent) comprehensively explains how pervasive the complexity of the mischief and the level of the misunderstanding of the exact nature of this highly unpredictable Deity called Èṣù Ọba Ọ̀dàrà (who especially had his abode at crossroads) across all the strata of our society in general and spiritual communities in particular. Èṣù is a very temperamental Deity in the pantheon of Yorùbá Deities, and the embodiment of two-edged swords approach to every and all issues. He is a very skillful Divinity who always does his work and performed his duties effectively in exceptional circumstances and extremely extraordinary ways. He is actually a Personification of Mischief; he is the one who teaches everybody that there are always two sides or more to every issue. And this primordial spirit did superb things! He balanced and created directions. Èṣù is so necessary to an ordered life! Èṣù is the real Messenger not only to the Olódùmarè but also to the other Irúnmọlẹ̀s/Òrìṣàs. He is also the intermediary between Ajoguns (evil spirits) to the Irúnmọlẹ̀s/Òrìṣàs and the ẹ̀dá èèyàn (human beings); he is the one who distributes, and also supervises the distribution of sacrifices (ẹbọ) to the Ajoguns; always. Èṣù is always in the middle of divergent world forces. He controls and regulates the two extremes - the world of happiness, joy, and fulfillment, as well as the arena of destruction, hopelessness, and sorrow. Èṣù always demands from those who have to give to those who demanded it within the premises of sacrifices, rituals, and propitiation. He maintains the delicate balance of good and bad - just and unjust. He protects towns and villages, Priests and Priestess (àwọn Ẹlẹ́gùn - tí wọ́n ní ẹ̀rẹ́ ní Ìpàkọ́, and Devotees and Awos against evil machinations. And he always favours those that performed the necessary and appropriate sacrifices (ẹbọs) and other forms of rituals; "ẹni tó bá rúbọ l'Èṣù ń gbè"! On this, Ifá says in Ọ̀yẹ̀kú Òtúrúpọ̀n (Ọ̀yẹ̀kú-bàtúrúpọ̀n): Orí eṣinṣin ò níná Afì-ínìn-ín Afì-ọ́hùn-ún Ìrù ẹṣin ò gbébìkan A dífá fún Bèlèké Òkú Ìgbọ̀nná Ọmọ olówó ẹyọ Èṣù kóre wá Ẹlẹ́gbára kóbi lọ Bèlèké darí ọrọ̀ ṣáwo nílé The housefly head bears no louse It swings back It swings fort The horsetail swings pendulum-like Cast Ifá divination for Bèlèké Dead man in the city of Ìgbọ̀nná The owner of cowries Èṣù bring blessings Ẹlẹ́gbára chase away evils Bèlèké ushered wealth to the household of initiates. Èṣù Láàlù is a bosom friend, working partner, confidant, and close associate of Ọ̀rúnmìlà Baraà mi Àgbọnnìrègún, the one who practices and teaches Ifá - an esoteric language of Olódùmarè (containing the divine message of life) through a very complex divinatory system, and who also teaches wisdom. Ifá says in Ọ̀ṣá Ogbè (Ọ̀ṣálogbè): Bí a bá rí ọlọ́rọ̀ ẹni Ṣọ̀rọ̀-ṣọ̀rọ̀ ni àá dà A dífá fún Ọ̀rúnmìlà Ifá yí ò ma ṣe awo pẹ̀lú Èṣù Ọba Ọ̀dàrà This is why the Babaláwos in the very ancient city of Ilé Ifẹ̀ used to praise Ọ̀rúnmìlà Baraà mi Àgbọnnìrègún as "Mòpó Ẹlẹ́jẹ̀lú" - the friend of the one who always loves animal blood. Èṣù Láàlù left Ilé Ifẹ̀ and went to orílé Kétu where he actually enjoyed a large following and devotees, and he was very famous and popular with the king of the ancient city (now in the Republic of Benin). He was later chased out of Kétu in controversial circumstances after his public fight with the monarch of the city - the Alákétu and returned back to Ilé Ifẹ̀ from where he later went to Ilé Adó Èkìtì to be living with Ọ̀rúnmìlà Baraà mi Àgbọnnìrègún, and both of them eventually returned to Òkè Ìtaṣẹ̀ in Ilé Ifẹ̀. Here, Ifá says in Ọ̀wọ́rínṣogbè (Ọ̀wọ́rín - Ogbè): Ìdúró ni wọ́n fi ohun odó fún odó Ìbẹ̀rẹ̀ ni wọ́n fi ohun ọlọ fún ọlọ A dífá fún Èṣù Ọ̀darà Yóò fọ́ orí Alákétu Ohun tí ẹ bá rí Ẹ fún Èṣù Kí Èṣù ó gbà Kó lọ Ohun ẹ rí Ẹ f'Éṣù

Èṣù historical records, narratives and facts of history

Curiously, some educated Babaláwos, and for reasons best known to them are now busy themselves with the disgusting project of changing historical records and narratives and facts of history by asserting falsely that a particular terrorist/bandit and a mere historical figure who goes by the nickname, "Èṣù" is the "one and the same" our dear primordial Divinity popularly known as Èṣù Láàlù Ẹlẹ́gbára Ọ̀gọ - Ẹbọra tí jẹ́ Látọpa. After the crushing defeat of the Ìlọrins at Òṣogbo in 1840 and Ìbàdàn ascendancy, the Ìlọrins ventured no more into the Ọ̀yọ́ provinces, except for the little help they endeavoured to give to the Ìbàdàns during the Batedo war, by attempting to besiege Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́, which ended disastrously for them. They appeared now to have recovered somewhat from their military depression, at least sufficiently to essay aggressive warfare into the Ẹ̀fọ̀n Districts. A man called Èṣù, a native of Ìyè, a town between Ilémoso and Eluku who had been a slave at Ìlọrin was redeemed by one Lálẹ́yẹ for 12 heads of cowries, the later also redeemed one Òní for 25 heads of cowries and gave her to him as a wife. Èṣù, however, turned out to be a ne'er do well of a roving disposition, unfit for any trade. He left Ìlọrin and settled first at Ẹ̀gbẹ̀ then Ìtagi and finally at Ìṣàn, leading a predatory life in those regions, kidnapping peaceful traders, sparing none, and was particularly hard on the Ìlọrin traders. In that way he became a person of some importance in those parts; hence the Ìlọrins were now resolved upon capturing him alive. Finding himself obnoxious to the Ìlọrins, he hastily declared his allegiance to the Ìbàdàns their great antagonist. Through the assistance of Olúòkun, a distinguished Ìbàdàn gentleman residing at Ìlá Ọ̀ràngún, he received an introduction to the Baṣọ̀run Olúyọ̀lé of Ìbàdàn (then living) who received him cordially, and in dismissing him, gave him a war standard and commended him to the care of Yemọja, his tutelary Deity, Olúyọ̀lé, being a very Orisa minded man in his own way. In his incursions, Èṣù never forgot his patron, for, during the Baṣọ̀run's lifetime, he continually sent him slaves and booty in his raids. After the death of Baṣọ̀run Olúyọ̀lé, the Ìlọrins were resolved to besiege Èṣù at Òpìn where he then was. Ali, the brave Balógun of Ìlọrin was entrusted with this expedition. He sought the alliance of the Ìbàdàn chiefs, as the relation between Èṣù and Ìbàdàn was only a personal one with the late Baṣọ̀run; and besides, the Ìbàdàns were somewhat under an obligation to Ìlọrins for assisting them in the futile siege of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́ during the late Batedo war, but as a matter of fact in order to forestall his opponent. Although any pretext however small was quite sufficient as an excuse for the Ìbàdàns to mobilize, in this case only a junior war chief named Kòlọ́kọ́ with a small force was sent to represent the Ìbàdàns. For three years, Òpìn held out heroically and was nearly baffled by the prowess of Ali when a sudden accident occurred which extinguished their hopes. Aganga Adoja, a noble citizen was the hero of the town; one-night Aganga was inspecting his magazine with a naked lamp in hand when suddenly a terrific explosion was heard and the hopes of Òpìn with her heroic defender perished together in a moment. Èṣù escaped to Ìṣàn, thence to Ọyẹ́, and then to Ìkọ̀lé. These places were taken one after another as Èṣù was being pursued to be taken alive. He escaped finally to Ìjẹ̀lú, a place fortified by nature against primitive weapons of warfare, situated on a high hill, and surrounded for a mile on all sides by a thorny hedge and thickets, it was impenetrable to the Ìlọrins horse. Ire ni o! Reference: The History of the Yorùbás by The Rev. Samuel Johnson. Aderemi Ifaolepin Aderemi (Olúwo Ifáòleèpin) The Founder and Chief Coordinating Officer Society for the Ifá Practice in Nigeria (SIPIN) Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Your Orí Is Good, You Are The Problem!

ORÍ is the source of all beings, this is why she is called "ÀṢẸ ẸDÁ", meaning "The Power/Source within every being". ORÍ can transform from one form to another without losing her authenticity. This means by default, you can transform from one form to another as well because you are ONE with ORÍ. But your ability to transform from one form to another without losing your authenticity depends on how well you manage yourself. If you know how to manage your Ìwà(Character), you can peacefully transform from one form to another and still remain untouched. But, if you don't know how to manage your ìwà in such a way that it aligns with your ORÍ, you will become vulnerable and those who know how to manipulate energies can make you change from what you are supposed to be, into what they want you to become, whenever they want. They are able to achieve this because we all are CREATORS, we all have the àṣẹ to create whatever we want to experience. So for this reason, anyone can make you become miserable, as long as it is what they want, it will come into reality. And on the other hand, because you are also a creator you can choose not to become miserable, and your wish too will come into reality, but it all depends on how deeply rooted you are. The wicked ones can't destroy your ORÍ, because ORÍ can't be destroyed! they can only make you become miserable, and this will happen when you are not in alignment with your Orí. But the moment you wake up to this truth that: We are creators, every soul has the power to create what he/she wants to experience, every soul has the power to transform from one form to another and ORÍ can never be destroyed. Then, you will receive a breakthrough and take back your Àṣẹ. Food rituals alone can't deliver you from the hand of wicked manipulators, you have to be in agreement with the above truth first, then rituals, if you want. IFÁ says in Irosun Ogunda that: No Orí is unfortunate, one's character is what makes it seem like it's unfortunate. If you can fix your character, you have fixed your life. May we all have the courage to fix our character, so that we can enjoy grace in abundance? Àṣẹ. Is this helpful? Message: Efe Mena Aletor Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Williams Shakespeare, “King Charles III,” Act 1 Scene 1, (#2).

KING CHARLES: Behold! Oh, Apparition. If you must speak for your people, do it now. Or remove back to whence you came. It is night and Camilla and I long for the comfort of our bed. EGUNGUN: Address me by my name, I already told you who I am. Or, as it is the fashion of your people, are you poised to rename me? For there is no place you go that do not re-name, as the original name of that land is never good enough for you. Rather than ask them, “What is your name? What is the name of this place?” Never, you say: “I name you Monday because I met you on a Monday afternoon. And I call this land Silvercoast, because I see you have silver all over this country. It is no more your land or your country. It is now part of my Commonwealth!” From whence this uncouth egotism feeding your arrogance to all native peoples? KING CHARLES: What you call arrogance, Strange Being, is what we call custom. It is the custom of our people to place our stamp on all things we see, meet or fancy. I see you have a strained accent. Is English your second language? Where, indeed, are you originally from? EGUNGUN: English is not my second language. It is a tongue I loathe to carry. I speak English to you, not by desire but because you learned none other vernacular beyond English. Must I like a tongue that has become a plague unto my people, such that it kills off the original language of our ancestors? Indeed many are those of my people who now swear on your ‘perfect vernacular, whilst they gradually fail to speak properly the language of their forebears. KING CHARLES: You blame us for every ill of your tribe! Phantom, be for once at least grateful! We taught ye language! Thou ingrates, ever full of limitless ills. EGUNGUN: To what avail is this thorned vernacular you taught me, which you turn around and call language, only to call my language vernacular? KING CHARLES: Enough tomfoolery tonight, apparition. Say what you have come to say. For to my bed, I must go. The night is fallen. EGUNGUN: Not unless you call me my real name will I let you rest. I am not a masquerade as your people and art historians have named me. I am Egungun. Say my name and say it well. KING CHARLES: It is a name heavy and stinging on the tongue: E-gone-gone! EGUNGUN: Say it again, or for you, there’s no respite tonight. KING CHARLES: E-gone-gone! EGUNGUN: Again! KING CHARLES: E-gone-gone! EGUNGUN: Again! KING CHARLES: E-gone-gone! EGUNGUN: Good. Now listen carefully. I bring you many queries from my land. (to be continued). Read the full article

0 notes