#on persephones title card and got the wrong frame

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

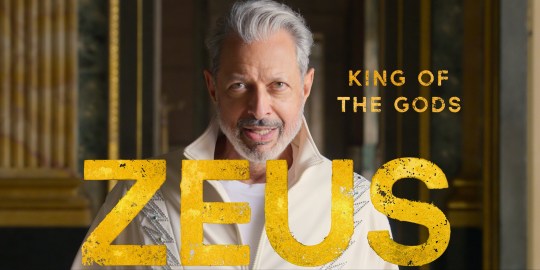

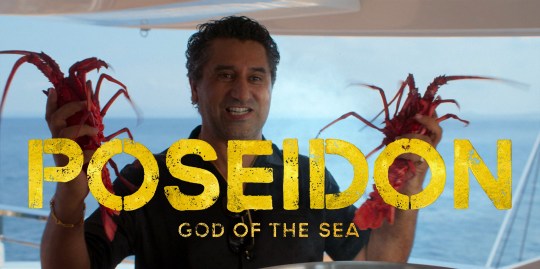

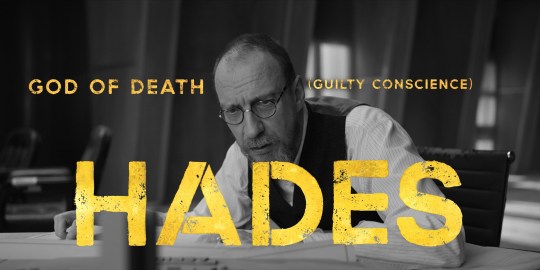

Kaos

The Gods

#captains log#Kaos#Kaos edit#buckle up folks#ive scheduled some posts#i messed up#on persephones title card and got the wrong frame#and now people r taking it as fact and being weird about it so um knock it off and also my bad and also uh oops#i was overzealous to post these#classic me

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeds of thought : Wicdiv #25

So, did you know midterms season is upon us ? I’m sure this has nothing to do with my subject of choice this month. I’m not projecting, you’re projecting. Anyway, thoughts and opinion on the new issue, spoilers below the cut.

ONLY GOD CAN JUDGE ME, TAG, YOU’RE IT

You’ve got to admire the wicdiv team’s relentlessness when it comes to stuff we’d all rather forget : if last issue only gave us a glimpse at the weight on everyone’s shoulders, this one tackles it head on (or off, depending on your point of view). Whereas last month we dealt with drives, this issue seems to revolve around responsibility, or perhaps more specifically accountability.

In a typical wicdiv fashion, this theme is pictured multiple times throughout the issue in various framings to paint a more global questioning of the concept and how it could apply to our characters. Accusations and excuses fly left and right : can Woden be held accountable for helping Ananke ? Baal for believing in her lies ? Amaterasu for leaving Mini ? Persephone for killing people whenever she pleases ? And as a coronation, an early contender for this year’s biggest “wait… is this our fault ?” shows up at the window.

What surfaces from all these particular situations is a debate on the very nature of responsibility : what makes us accountable for our bad deeds ? Who we are or what we are ? Inverting the question, can someone’s bad actions be justified by their specific personality, meaning we shouldn’t expect the same from everyone ? Or should the same behaviour and standards be enforced on every person, which begs the question : what about someone who isn’t a person ? What can the laws of men mean to them ?

Obviously all the characters have their own idea on the subject. For Cass, who still considers them all as human, the rules of society are still absolute. You don’t kill people on a whim, “you just don’t”. And not just because she refuses to cover it up, but because you cannot be human and think this is a good idea. Baal, on the other hand, takes into account one’s personality before judging them : the right thing to do for Ammy would have been to save Mini, but she’s not the kind of person who had the strength to do what was right. He also applies this logic to himself and clearly feels guilty for believing Ananke, as he should have known better. But note how he refuses to share this burden with Persephone : he is to blame for acting pretty much the same as the others, but it doesn’t mean the others are as well. It’s about who you are and what should be expected of you in that regard.

But of course the biggest antagonism in the issue comes from Persephone facing Woden.

Confronted with his bad deeds, Woden makes excuses resting exclusively on who he is : he’s weak, a coward, and in a bad place. His understanding of the world is such an egocentric one that what he could do in his situation becomes the norm ; that someone else might have acted better is irrelevant since he could not have acted that way. It’s interesting to note that in this context, his self-hatred is not a redeeming element but a defence mechanism who prevents him from having to change his ways to be a better person : he may be a little fuck, but it’s okay since he feels bad about it.

Persephone on the other hand has a deterministic approach to accountability : she considers herself exempted from the laws of men and even from morality. She is no person. Not only that, she’s doomed to a tragic fate. If it’s not going to be okay, why would she “do the right thing” ? In the most enlightening bit of their exchange, to Woden saying he was “in a bad place” Persephone replies “I’m in Hell. Join me.” Woden’s bad place is a personal one, defined by his relationship to others, while Persephone’s bad place is her own realm, one she necessarily exists in by the sole virtue of being who she is. And in this queendom, there is no system of justice or morality unless she wills it. Both Cass and Persephone see right and wrong as depending on your status, but while Cass places herself within the human paradigm of morality, Persephone sees the world from her position as a god. And within this frame of understanding, she’s not acting right or wrong because no human understanding of this dichotomy can fully seize the actions of a god.

And despite this attitude being clearly framed as her “going off the rails”, there is a case for it. The reason why the “let’s cover up Ananke’s murder or we’ll go to jail” plot device is so ineffective as a motor force (yes, this is a hill I will die on) is because the subject of the conflict between gods and human justice has already been dealt with in the Faust Act. We know what happens when gods are faced with a human understanding of their actions.

An interesting parallel can be made between Luci and Persephone in regard to the murders they committed and its consequences. The first arc spent so much time focusing on the murder Luci didn’t commit that it almost felt incidental that she indeed killed two people in cold blood ; no one, not even Cassandra, seemed particularly shocked or was made uncomfortable by that fact. Meanwhile, Persephone murdering Ananke is still clearly on everyone’s mind. That may be because Luci’s actions could still be linked to human standards of right and wrong. Whereas self-defence is but a cover-up story in Persephone’s case, Luci killing the shooters actually comes devilishly close to actually being self-defence. If I can go all law monkey here for a second, two things are required for your action to be justified as self-defence : an actual or imminent unjust threat to your or someone else’s safety, and for your response to be reasonable in regard to the threat. However, if the first element is verifiable given there were humans in the room, the second is impossible to demonstrably satisfy or deny : how could one prove that Luci acted reasonably in regard to the threat, given no one truly knows the extent of the gods’ power ? Could she have stopped the threat some other way ? Who is to say a murder isn’t a reasonable response given how important the gods are to the fate of the world ? A miracle, after all, is beyond explanation.

Luci’s mistake was to place herself within a human paradigm of justice while acting in a way that couldn’t be accounted for within that paradigm. Her trial and imprisonment demonstrates the failure of trying to apply human justice to an act of god. Persephone has no intention of playing by human rules. To gods, godly rules only must apply. But given how small and unstructured the pantheon is, this means that Persephone is living in a vacuum of societal rules, morality, and since Ananke’s death, necessity. Nothing is just, right, fair, or even necessary. The god society has lost its only objective criteria in the form of both its authority figure and the purpose of their actions. There is no scale on which to judge Persephone. When she writes she’s “no person”, are we to assume she meant “I am a god” or, in light of the 1831 special, “I am a monster” ? Who’s to say when there’s no judge, no jury and no executioner ?

… Until the issue’s last page, that is. The apparition of The Great Dark, with its lack of head, going after the very god that was to be sacrificed to cast it away, has every chance of being the direct result of Persephone’s actions. It is purpose, wrong to a right, wrong waiting to be righted. The structure the god society had been missing, something to base yourself on, something to be judged by. It is responsibility barging in Persephone’s Hell and demanding its due.

Unless it isn’t. Unless its apparition was unavoidable, and nothing Persephone or anyone else could have done would have prevented it. Unless it was never going to be okay. The only one who might have known the truth is dead. Worse, nothing the gods can uncover can ever be fully trusted. Some will believe they’ve to take responsibility for what they’ve done, and others will refuse the bear the blame because it was destiny. Either way, the proof they would be required to achieve is an impossible one. In law studies, we have a name for this. Probatio diabolica. The devil’s proof.

WHAT I THOUGHT OF THE ISSUE :

So New Year is a time for good resolutions, right ? How about I take up fairness this year ?

So how about that Cass/Woden dialogue ? Cass is still the greatest right ? Oh, and the evening family scene, so sweet. Loved the Anna Karenina reference, in fact all the title cards were great. Persephone’s hair deserves a mention on its own. And that underground scene ? Right up there with the best wicdiv scenes ever, right ? The art, which I ALWAYS forget to give credit to because I’m such a non-artistic person myself, was just breathtaking.

Am I in the clear ?

*deep sigh*

Alright, let’s talk about that damn cliffhanger.

If you’ve read… well, anything I’ve ever written, you know I mostly look for two things in a piece of media : characterization and narrative structuration. Concerning the former, Wicdiv has never let me down : I genuinely believe it is a masterpiece of modern character development, for comics and beyond. But everytime I’ve felt only so-so about an issue, which really wasn’t that often, I could pinpoint the latter as the origin. In most cases I could confidently affirm that these were objective problems that had nothing to do with my personal tastes. However, when I’m faced with something like this cliffhanger, I’m left wondering whether I’m fairly analysing it when I say it was a terrible idea or if it’s a solid development I’m unfairly judging by my own preferences.

I’m sure I’ll find some to say there is no such thing as an objective analysis and that our personal preferences always come into play, but I’ll have to respectfully disagree with these people. There is such a thing as making a mistake when telling a story. I sometimes say when commenting an issue that it is “the best version of itself”. What I mean isn’t that I agree with everything the story does, but that it found the way to make the least possible mistakes to achieve what the story achieved, and that changing a single thing would completely stray from which story the author has chosen to tell and how they chose to tell it. But to analyse things in that perspective, you have to acknowledge that the story that is told and how it is told isn’t necessarily what you would have liked. And I think this time, I may be stuck at that step, both for what the story is and how it’s told.

Let’s talk about form first. I wasn’t reading comics growing up ; I might have been 20 the first time I picked one up. As a kid, I only ever read books, and mostly XIXth-XXth century French classics. My understanding of narration is still deeply rooted in the codes of this particular era and medium. And if there’s a staple classic books just don’t have, it’s cliffhangers. Why would they ? The answer would be right on the next page. Imagine every chapter of a book ending on a cliffhanger. Comics, on the other hand, derive more from strips and serials than they do from books, and so come from supports in which cliffhangers are the normal way to end an issue.

Cliffhangers are something I just don’t like, because my appreciation of narration comes exclusively from books. To me, it will never stop feeling like a cheap way to provoke thrill that isn’t actually there, a little artificial bump in the story that undercuts a broader rhythm to it. In this particular case, that’s two issues in a row that end on a one-page new brutal development, which ends up feeling repetitive instead of show-stopping. Not only that, it takes the thrill out of reading the next issue, since every cliffhanger has to be quickly solved or redirected in the subsequent chapter.

But then again. If I try to be objective, I can’t think of a different way to introduce this new development. I may not like it, but where are you going to bring up a giant ball of darkness and doom capturing a child but in a ridiculously over-the-top cliffhanger ?

So even if I’m not a fan of cliffhangers, I think my problem comes much more from where the story is going with this. I’m probably harsher now that I’ll be after a few days, but I just hated everything about this scene. It casted a shadow over the entire issue, possibly the entire arc, both of which I was loving so far. Just to list a few things, poor Mini is apparently forbidden to get even the slightest characterization before she has to go back to being damsel in distress #1. Baal’s one-liner is nonsensical, except if the Great Dark has been coming by his window to say hello every Friday after eight, in which case you’d think he would have mentioned. Mini standing saying “what’s wrong ?” while the windows shatter behind her is my new contender for Most Cliché Thing wicdiv has ever done. And like I said, the very nature of a cliffhanger means we just know the supposed “battle” isn’t going to be the crux of next issue, meaning this setting is just pointless.

But I’m even more pissed on a deeper level : bare what I said earlier about responsibility, what exactly is a Big Bad Scary Dark Thing going to bring to the story and our protagonists ? What are our characters supposed to get from facing a faceless swarm of black ? That Ananke was right ? We’ve had four arcs with a complex, tortuous villain and we’re ditching it for goth Sharknado. I hate this for the same reason I hate every movie in which the villain is a dinosaur : it’s big, mean, ugly and that’s it. It takes space and tells us nothing. I would much rather have had every single god wanking around for 5 arcs until total self-destruction than this.

BUT.

THEN.

AGAIN.

Mini getting kidnapped again is a very telling clue that this figure is linked to the ritual, and Baal actually having seen the Great Dark can still find an explanation somewhere. Gillen has said upfront in the latest notes that this arc will be about self-indulgence, so I can’t fault him for going with the clichés. As for the deeper stuff, it’s still way too early to tell exactly how the great dark will feature as an opposing force, or if it will at all. Maybe it’s just going to disappear with Mini in tow and the gods will be left wondering what to do. Part of why I am so angry at this development is definitely me : I like human villains and dark mirrors. Non-sentient or one-dimensional antagonists is something I have zero interest in. I was probably also taken aback by how Persephone gets exactly what she wants in this issue, a force she can battle with even less remorse than Ananke, when I’d identified this arc as the one Persephone would finally have to deal with herself. So, points for unexpected direction. Or hell, maybe I was still right, and the real danger will come for the gods’ incompetence in handling this. Oh, and maybe this new player will reveal itself to be an old one, or even a current one in disguise. Theories are already floating around.

So yeah, I’ve got nothing. I hate this, I really do. It’s not the story I want. But it may still be the best version of itself. We’ll see. As a good resolution this year, I am trusting artists with their work.

22 notes

·

View notes