#of my music consumption is cds and mp3s

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

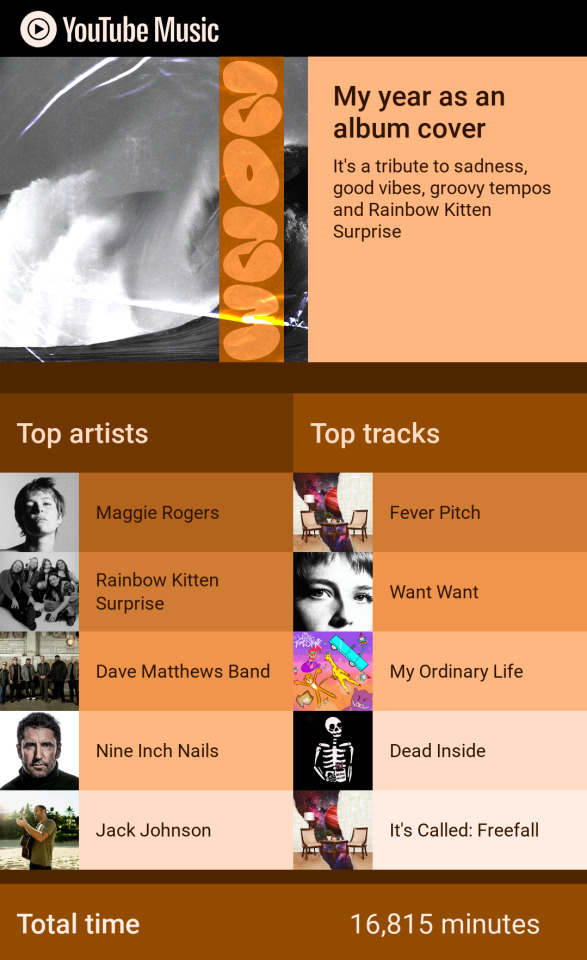

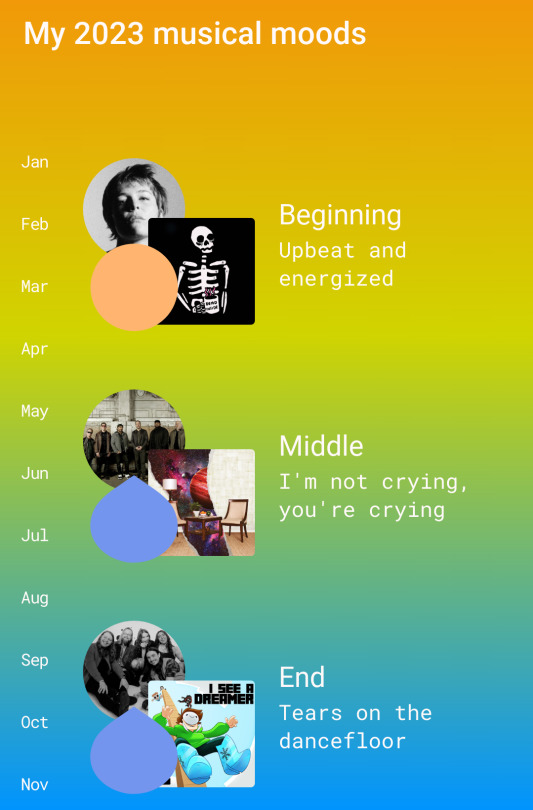

#i don't do spotify sigh#but youtube music started a recap last year or the year before#glad to see they're keeping it going#this is sort of accurate#the inaccuracy is that i own mp3s and cds for my favorite artists and listen to their music a lot more than this would lead one to believe#i only use youtube in the car for stuff i don't have on cd (which is probably why there's a lack of dmb and tool and nin in my top tracks)#tool is missing completely which is a surprise#i can't believe my ordinary life and dead inside made it on my top tracks#ahahahahaha#maggie and rks do not surprise me#youtube recap#music#about bri#dying at i see a dreamer on the musical mood#that is one from my youngest#he uses my phone+aux in the car sometimes#long story short#this is a fairly accurate snapshot of my streaming listening but does not reflect my overall listening because at least half (if not more)#of my music consumption is cds and mp3s#love

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

since we are on the topic. Again no pressure to anyone buying stuff... you do you. Just there seems to be this idea that there is all or nothing with albums and I think that's not really right. For me personally: I like to own media. I am not a big fan of subscription services like Netflix and Spotify even though I do use both of them. Because I am accutely aware that I own nothing on there. With Spotify I am even granted access for free if I don't mind the adds which is nice because I like free music. But if I do decide to pay that still does not stop them from taking the songs I like down for various reasons. It has happened a few too many times where there are just holes in my playlist for this or that reason kpop and western music alike (which like fair if artists wanna renegotiate with spotify over their payout they should it's their music but at the same time hey hi I was listening to that so I am annoyed now). And so yeah if I like a song nowadays I will try to buy it legit off itunes - if I like a whole album I will try to buy the physical CD, and if I am broke... well nobody tell Baekhyun this but I was never gonna spend 60 bucks on his japanese solo debut so I youtube mp3 converted the songs and saved them to my computer and later burned them onto various mix cds i like to use in my car. The way I see it the capitalistic consumption aspect of kpop is really wild and I do not think you have to fully give into it but I also don't think you have to fully reject it. For instance I bought DVD box sets for shows I liked in case they ever vanish of netflix - I do not buy every show I ever watched just the ones meaningful to me. Kpop albums are the same. I will not buy every release. But if I have the means and I like the album sure I can buy a select few for myself and I have bought a few of them used without photocards because I do not care about the collection aspect of it I just want the music on the Disc. Having them is like having any form of media. Something no one can take away from me. If Stray Kids quit tomorrow and get into a legal battle and all their content gets taken off the official channels I will still own the 2 albums I bought and I will keep them until Chan himself breaks into my house and steals them off my shelf. So that's where I am coming from. Again nothing wrong with not wanting to buy albums. Just wanted to give my opinion on it basically

idk if you read the original ask about why i don’t buy albums but im not fundamentally against buying albums and i don’t have that all or nothing mindset that some people have (although i think those people are just part of a loud minority). it’s just not for me because i know that personally i’ll probably look at the photos once and then never look at them again. i also don’t have a cd player and don’t plan on buying one so i don’t have any use for a cd. there are plenty of reasons to want to an album and owning the physical copy of the music is certainly one of them! streaming services suck and i get not wanting to rely on them for your music. i’ve had songs i really love get taken down or even switched to a completely different version of the song and that wouldn’t happen if i owned the cd but that’s the trade off with streaming services. i prefer to save the money i would be spending on albums and put it towards concert tickets which is something i know i will love.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I clicked "other," because by amount of time listened, almost all of my music consumption is over terrestrial radio.

For paid music, it's CDs and occasional MP3 downloads. I have a USB-connected CD drive specifically so I can rip CDs to my music collection. When I pay for music, I would like to own it.

im very curious as to what people use as someone who doesnt use spotify

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Music Distribution in the 21st Century: From CDs to Cloud-Based Libraries

Music is an ever-evolving art form, and its distribution has transformed drastically over the past few decades. From the convenience of compact discs (CDs) to today’s cloud-based libraries, each advancement has made music more accessible, pushing the boundaries of how and where we listen. Understanding how music distribution has changed over years allows us to see just how far we’ve come—from a time when physical media dominated, to today’s virtually unlimited, on-demand music libraries. Platforms like Deliver My Tune have adapted alongside these changes, helping artists bring their music directly to listeners across the world, regardless of location or device.

1. The Rise and Fall of Compact Discs (CDs)

In the late 20th century, CDs became the standard format for music. They offered a more durable, higher-quality sound compared to vinyl and cassettes, quickly overtaking them as the preferred medium. Music lovers enjoyed the ease of purchasing, sharing, and collecting CDs, which offered an attractive blend of sound quality and portability. Record stores flourished during this period, with CD sales dominating the industry and fueling a massive boom in physical music consumption.

However, CDs also had limitations. They required physical production and distribution, which incurred significant costs for record labels. Artists were still largely dependent on labels for distribution and promotion, as it was nearly impossible to independently press and distribute CDs at scale. Additionally, while CDs were portable, listeners had to carry their entire collection if they wanted variety on the go. But as soon as digital formats became more widely available, CDs began to lose their hold, eventually giving way to the digital revolution.

2. The Digital Download Era: Owning Music Files

The advent of the MP3 format and digital download platforms like iTunes brought a fundamental change in how music distribution has changed over years. With MP3 files, listeners could store thousands of songs on personal devices, forever changing the concept of a music library. For the first time, music could be easily purchased, downloaded, and accessed without any physical component, which was a game-changer for both artists and listeners.

Digital downloads introduced the concept of owning individual songs rather than full albums, allowing listeners to curate their own libraries. Artists and record labels benefitted from lower distribution costs, but they also faced new challenges, such as piracy, which surged with the availability of MP3s and file-sharing networks like Napster. Despite these challenges, digital downloads paved the way for greater accessibility and new monetization models, making it easier for both major and independent artists to reach audiences.

3. The Shift to Cloud-Based Streaming Services

Today, music streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music have become the dominant method of music distribution. Instead of purchasing individual tracks or albums, listeners can pay a monthly subscription to access millions of songs instantly, from anywhere with internet access. This cloud-based distribution model is another huge leap in how music distribution has changed over years, allowing listeners to access vast libraries without needing to store files on their devices.

Streaming services not only provide accessibility but also contribute to music discovery. With curated playlists, algorithm-driven recommendations, and shared playlists, users are exposed to a wider range of music than ever before. Independent platforms like Deliver My Tune have been essential for helping artists get their music on these major streaming platforms, ensuring that artists retain control over their distribution while reaching a global audience.

4. The Financial Shift: Subscription Models and Royalties

While streaming services have made music accessible, they have also introduced a controversial royalty model for artists. In the CD and download era, artists received royalties based on album or track sales, with revenue tied directly to each purchase. In contrast, streaming pays artists on a per-stream basis, which often results in lower payouts for independent musicians, especially when compared to physical sales. Although some top artists benefit from millions of streams, most independent artists receive modest royalties despite having their music available to a global audience.

This shift has sparked debates over fair compensation, with some artists calling for reform within the streaming industry. Independent artists often need to diversify their income streams by selling merchandise, touring, or using crowdfunding platforms to support their careers. Nonetheless, streaming offers significant benefits in terms of reach, as any artist’s work can be instantly available to millions of listeners across the globe. For many, this visibility outweighs the lower royalties, as they can gain fans and build their reputation more easily than in the past.

5. Music Discovery: The Role of Algorithm-Driven Playlists

One of the biggest advantages of streaming platforms is music discovery. With traditional media, discovering new music often relied on word of mouth, radio, or music stores. Streaming platforms use data and machine learning to recommend songs and playlists tailored to individual users’ preferences. Algorithm-driven playlists, like Spotify’s Discover Weekly or Apple Music’s New Music Mix, make it easy for listeners to discover new artists and genres.

These recommendation systems not only make discovery easier for listeners but also help independent artists gain exposure. Previously, small or emerging artists struggled to gain visibility without the support of a record label. Now, they can reach listeners based on taste and genre, leveling the playing field and allowing a more diverse range of artists to find their audience. For fans, this has opened up a whole new world of music, as they can discover artists from around the world with a few clicks.

6. Cloud-Based Music Libraries: The End of Ownership?

Cloud-based libraries have given listeners access to vast catalogs of music without the need for ownership. This shift has redefined what it means to “own” music, as most people now “rent” music through subscriptions rather than purchasing physical or digital copies. While some listeners miss the tangible connection of owning music, cloud-based libraries have won over the majority by offering convenience, unlimited access, and effortless storage.

For artists, the cloud-based model means that music can be distributed faster, reaching audiences instantly after release. Distribution platforms, including Deliver My Tune, have made it easier for artists to release music directly to streaming services, speeding up the timeline from production to audience and enhancing artists’ control over their creative process. This system has democratized music distribution, making it possible for artists of any size to share their music widely.

7. The Future of Music Distribution: Virtual Reality, NFTs, and Beyond

As technology continues to evolve, the future of how music distribution has changed over years is bound to bring more innovations. Virtual reality (VR) concerts and interactive experiences could become new ways for fans to engage with artists. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are also gaining popularity in the music world, allowing artists to sell exclusive digital versions of their music as collectibles. This model creates a sense of ownership and uniqueness in a streaming-dominated landscape.

Blockchain technology is another potential game-changer, as it could allow for more transparent and efficient royalty distribution, providing fairer compensation to artists. Artists may increasingly turn to these new technologies as a way to stand out and offer unique experiences to fans. While streaming will likely remain a central part of music distribution, these innovations may add new layers to the artist-fan relationship, enhancing how listeners experience music.

Conclusion: From CDs to cloud-based libraries, the evolution of music distribution has continually redefined our relationship with music. Each step forward has brought music closer to listeners while providing new opportunities—and challenges—for artists. As we consider how music distribution has changed over years, it’s clear that platforms like Deliver My Tune are instrumental in helping artists navigate this changing landscape, providing a bridge between creators and listeners in the digital age. Looking ahead, the future of music distribution will likely bring even more innovation, making music more accessible, personalized, and dynamic for fans and artists alike.

0 notes

Photo

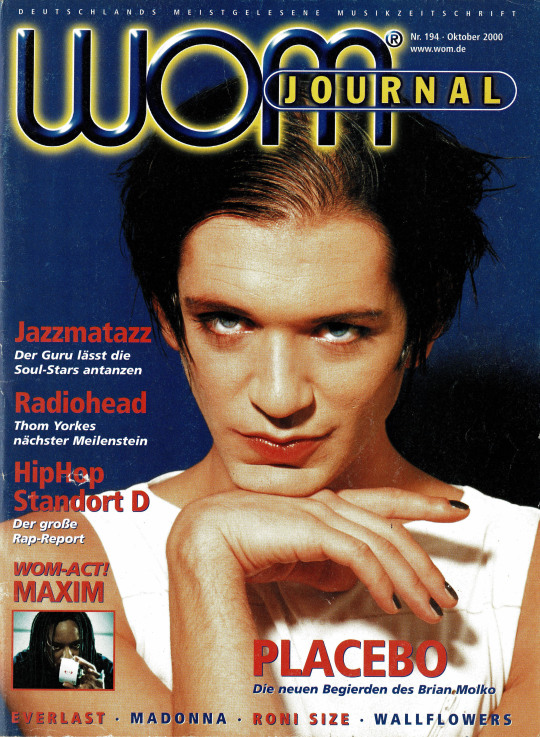

Wom Journal - Oct 2000

(really, really awful google translate of the OCR scanned text below the cut)

The desires of Brian

More serious topics, healthier lifestyle more

Responsibility hopes to satisfy her third album

PLACEBO their greed for change

As a placebo in 1996 with their Seat but on the English Musitnar they offered the dazzling alternative ill de inogenic bands of Brit pop. Yours Guitar rock that was clearly ambiguous tare .. Frontman Brian Molko and the urge ZtegülnICKee they turned around self-shielding lings of the music press Provocative sayings dent 'former drama student Molka about the cast Lippert. Times he sold Sex monster, sometimes he flirted with his consumption. Placebos self-destruct trip - Frustration and emptiness that the band Asii at dee, attended their second AlburnWITHOUTIfretVM Accompanied NOTHING "We milked our music like Cow. "Molko leans on the Hoteldnigl his voice is deep his americans ground despite the many years in Londortjkrbeai We are months with the songs about the Globilige * tours. Then when we went to the studio then a bunch of new pieces about ddlniibentAtni .1 + interest in wincler's own music , .. " wake up. "It took nine months for Placebo'.fQr third baby BLACK MARKET MUSIC. Instead of that. A superstar producer's ego below the band produced together with Patti Coikeft for the first time itself. Never before has it unlike trio so easy Record songs. Fun and friend- determined the studio atmosphere sphere. The one they usually take care of Rock 'n' roll lifestyle was behind the Music back "Today we are focused more, our music enjoys the first Priority, "says Brian Molko." Body It will also be more strenuous shortly before the opening we celebrated like in 1997. After that I couldn't move for three days was the slogan for the studio: the party is over. Henceforth health food diet " This time placebo were on the “collaboration trip, "says Molko. On the electronic rock single" Taste In Men "Caroline Finch from the Brit band Ling- leum the BacIdngvocaLs. Rob Ellis, drummer from PJ Harvey, arranged the strings on the hidden. Track "Black Market Blood". And for that probably The most piercing piece of "Spite & Malice" filled the friend

Placebo singer 1341

itannitdti.dat word Oh

vet gold mine "we were like a hiba red, Film and am Hest * eiäältill dw But people are so. When we started, wielanges wore we Guth. Then we became the Glani.Bend But: mine is a movie, and placebo is that rea * lebeg,

US rapper Justin Warfield chanted the chorus. The approach to the US market is no coincidence. Was at the debut Sex d. I% Mai balm second Obilia11 which the Ban ' , to Aid SLACK MARKET MUSIC arctic american themes iep .. 'itch placebo 2000 with political: ii • MA (jipite & Malice "), the American pop 'Dissen of the parents ("Blackeyed") and init; , ! racism, ("hemoglobin"). "We lik '' always oppose any form of prejudice. ,, globin 'is our version of Billie Holidays b.,,, fruit of old jazz from the fifties .2 some strange fruit in the southern states sees dangling .. black people, .- ..; hangs whales. '" There is also on BLACK MARKET Placebo-typical love songs. But there are: telling and the characters that ie in the songs ebidergr Lind. "This is a natural Enrid. C3,21 3rd, BOnpritings. If you go to 30 jit you more on what's happening in the world : 'biletideitständig busy with yourself. Nap . make tin * nigh flitch angry. '., Ic

Minden, healed in the lyrics to zt4Inpatiev1isen degrees around myself '! • With BLACK MARKET MUSIC you have placeh various phases of self-experimentation Reliance level reached. Even if the complete • HUG of samples now live a backup key Molko leaves no need for it that their development is only successful well the badd of the synergy of the triangle, p, i, placebo works like a triangle. On. So it will never be even more than give. "KATJA 'SC

An offer, the role of Judas Priest in You refused to play "Metal God". I got the Hollywood script for a film with Jennifer Aniston and Marky Mark. At first I thought: Wow, this is Holly- wood! When I got to the second page of the script I said: No, • we are not rent-a-band for film bizz!

With the album title BLACK MARKET MUSIC associ is forbidden. Music on the black market is also a popular topic. The album title takes up what is currently on Napster and MP3 expires, the black market of the 21st century. It is attractive, something To have illegal things that are only available under the counter. But it is illegal if our album is in the Download the Internet from unauthorized sites. About it you no longer in control. It is not fair by an artist too expect him to work for nothing. Nobody works for free. Artists bear responsibility like everyone else. We want not living poor as Van Gogh. The artist life becomes novel represented by people. the hard work, the band brings with it, do not appreciate. It would be to these people no matter if we are hungry or unemployed.

As band members you all have a very different background. What welds you together?

We have the same ideas, the same goals, what we do with placebo want. We like the same drinks, vodka red bull in large Amounts. We all grew up with the feeling that to be more. That made us extremely independent individuals, and that's probably the bond that connects us.

You worked with David Bowie. Do you look at him like fans, or is it now? a friendship? It's definitely friendship. Placebo and Mr. Bowie have mutual respect for each other. Uncle Dave supported us before we even recorded the first album. With the Friendship has grown through time and tours, until it finally worked on "Without You I'm Nothing" came. It is indescribable when David Bowie calls you and asks: "Can I sing on your song?" And then it's natural incredible when this legend sings fin studio to your music. An absolute fulfillment for me.

It was probably a fulfillment. not meet for Calvin Klein lit placebo To take photos; which then biered in Prussia have never been published. ekuelleAmeri- Wasn't your butt 'Eärian Molko pretty enough? eg • qpitarrist, 27), My butt not pretty enough? You psexuals wanted me without makeup and in. ". ch de Stefan Olsclairriiirsist, 26) and oversized men's clothing images lietmovDirrnellsr nri H4witt I wanted to wear a skirt. Drummeh 21M out of the way. Molko and I didn't manipulate myself, A 5 first demos, leave as they would have liked. Her, Mtt acted as an alcikushilfsdrummer. The photos are then different from ChEm 1996 forth from their self-titled when she imagined it to be a Mairrer, D, LaPel, this time ben But at least I was able to use Robert Schultzlscrich * drums. Keep clothes. melee ii Jain luckid1 as she as - -stifle tour ein.Hewitt ,.> ,, A5A'A • came back to Drumm-lei Piacr? bo. About your buddy Marilyn ilf AnIriJrie VC'n Michgel Slkpe (REM.) You once corsored Manson, irk Dire Siind im says: "Marilyn makes the" Velrict Golf stefan". best blowjob. "Personal. cl: s yen steve orsbeirme: produ- • Experience with it? ricrte album l.'JlITHOkik 'irk!) I'M NO- Yes, but that's not exactly true. I flIflG 1999 it ii ilern theme song have never said that Marilyn makes the best DMett Florrvie again. With makes a blowjob. I already have the single hEvery 'feu, Every Me "on had better. em soundtrack "Ertl old angels" was INTERVIEW: KATJA SCHWEMM ERS Placulko still popular in Germany aier, Nettie CD: BLACK MARKET MUSIC.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The evolution of popular music consumption

We have entered a new era, the era of streaming. But before that, how did we listen to popular music and how did it change?

From the Phonograph to the vinyl, from the vinyl to the radio (that really popularised popular music). From the radio to the tapes, from the tapes to CDs, and finally from CDs to streaming.

In this post, we are going to focus on the era of the tapes and beyond. I’m a bit too young to have used a Walkman in my childhood, but it was a real innovation at the time of its creation in 1979. It was a new way of consuming popular music, outside of the private home sphere. For the first time, listeners could take their music wherever they went. This innovation helped the rise of tapes, which had some difficulties against the popular vinyl.

Not long after the invention of the Walkman, the CD appeared with the first popular music album pressed to CD in 1981. CDs became popular by the end of the 80s because they could include up to 60min of music in high-quality audio (also because they became cheap after their popularisation).

The rise of MP3 players with the incontestable iPod had a hard drive capable to hold up to 1,000 songs. I think that we have all been through that era, I do remember as a child to listen to music with an MP3 player, we had to download music ourselves (most of the time illegally), it took too much time. With time, streaming services started to emerge. The first being Pandora in 2005, Spotify following in 2008. That was a real revolution for us, listeners, listening to music became easier thanks to these platforms. It has also changed our way of consuming popular music, it became easier to share songs with friends, with the possibility of creating collaborative playlists on Spotify for example.

With the vinyl coming back to fashion, I was wondering how do you listen to music? If you use streaming services, which one and why?

I have not been in the details; I did not speak about the problem of remuneration of artists created by this type of platform. I mainly focused on the evolution of popular music consumption; this will surely be in another post.

Here’s my recommendation of the week: Smithereens by Twenty One Pilots.

Sources:

https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/the-evolution-of-music-consumption-how-we-got-here/

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

WV Converter To MP3, FLAC, WAV, AAC, WMA, AC3, OGG Avdshare

If it is advisable convert FLAC to MP3 in Mac OS X without cost, one of the simplest ways to take action is utilizing a utility referred to as All2MP3. Whether or not it's potential to successfully discover within a physical stream an audio body containing the target audio pattern. To seek on an audio file it's required to convert the audio sample number right into a file place where the needed audio data is stored. For a constant-bitrate stream like WAVE and MP3 CBR it's easy to seek out the wanted audio body in only one file seek request. convtoflac (usually) transcodes the file by piping the decompression output on to the flac command to make the method as fast as possible. If the -f possibility is used, nevertheless, the file should first be written out to a brief WAV file. On a multi-processor or multi-core system, transcoding a number of files will be done significantly faster by using the -t option to specify that multiple files ought to be transcoded concurrently. Lots of people rip their CDs to FLAC. They preserve the FLAC as a lossless archive on their arduous drive, and then they make MP3s or AACs for his or her portable participant. Convert recordsdata from wv to MP3,MP2, WAV, WMA, OGG, AAC, APE, FLAC, WV, TTA ,SPX,MPC,AC3 and MP4 to WAV and backwards. I highly recommend Avdshare Video Converter to Convert AVCHD to MP4, MOV, WMV, FLV, AVI, WEBM, and so forth for enjoying AVCHD on iPhone, iPad, Samsung, QuickTime, Home windows Media Participant, and so on or uploading AVCHD to YouTube, MySpace, Twitter, and so on.

WMA, OGG, FLAC, WAV. All2MP3 convert essentially the most used audio and video formats on to MP3. Free WV to FLAC Converter Online tool which is supplied right here helps with conversion of WV to FLAC much less consumption of to FLAC file Converter right here does not require any of customers e-mail signup and private data. I did notice it took a really long time for dynamic split to course of a drum monitor utilizing Wavpack in a recent project, so I will do as you beneficial and use wav for recording and enhancing and only encode to wavpack after a challenge is done. IDealshare VideoGo, the best wv to flac converter download filehippo Converter, can quick and batch convert WavPackwv to nearly all in model audio format on Mac or Residence home windows. Finest program to convert from kar to mp3 his comment is here: -kar-to-mp3 good piece how do I convert kar to mp3 on-line free even With the help of this versatile on-line audio converter, you could possibly be freely to listening no matter songs from on-line music web sites akin to Pandora Radio, MySpace, YouTube, Yahoo, , and so on at anytime as you like. It was subsequently nice to see that in December 2016, with the discharge of WavPack , we lastly have the inclusion of DSD knowledge compression into an open-supply file format. Or, within the occasion you at the least have the ffmpeg libraries put in, you want to have the ability to import the wavpack recordsdata into Audacity. WV recordsdata could also be effortlessly became FLAC through the use of our WV to FLAC Converter. Glossary WavPack (WV) permits users to compress (and restore) all PCM audio formats together with eight, sixteen, and 24-bit ints; 32-bit floats; mono, stereo, and multichannel; sampling rates from 6 to 192 kHz. One final format you may wish to take into consideration changing to is OGG Vorbis. Which is an open supply lossy audio format, like MP3, that can be a much higher quality. Comply with the previous the steps and choose OGG Vorbis from the drop down menu. Click on … to set up the quality, click on OK and then OKAY once more. It is going to ask you to find You possibly can download that here I always just get the generic one to make things simple. Extract the contents of the zip you get someplace, I like putting it in my Program Information, and rename it to simply Now Open it in Foobar and it will start encoding. WavPack is a free, open source lossless audio compression format developed by David Bryant. WavPack compression (.WV recordsdata) can compress (and restore) 8, sixteen, 24 & 32-bit float audio files in theWAV file format. It additionally helps embody sound streams and wv to flac converter download filehippo excessive frequency sampling costs. Like other lossless compression schemes the data discount charge varies with the supply, however it's sometimes between 30% and 70% for typical widespread music and considerably greater than that for classical music and completely different sources with higher dynamic differ. Convert your audio like music to the WAV format with this free on-line WAV converter. Upload your audio file and the conversion will start instantly. It's also possible to extract the audio track of a file to WAV in case you add a video. Converting FLAC information to MP3 or WAV. Would have liked to maintain my folder structure after conversion, as a substitute all the transformed information are together in a single big folder. Ogg FLAC is the compressed FLAC knowledge stored in an Ogg container. Ogg is a much more powerful transport layer that permits mixing several kinds of various streams (audio, knowledge, metadata, and so forth). The overhead is barely larger than with native FLAC. I did not strive the script as I'm having a little bit of luck, for whatever purpose, with decompressing thewv towav and then altering thecue file accordingly.

1 note

·

View note

Text

WV To FLAC Converter

To make use of the WV conversion characteristic simply add the files you want to convert to WV. Then click on combo-box to choose "WV" as the output format. Excellent app when you should manage input and output audio files of various codecs. A lot of them suggest various settings. The drawback, you can not perform the conversion in a fast and computerized manner. For that goal, I exploit Mp4 Video 1 Click for Windows (search right here or google) at the side of LameXP. So, being joined collectively, LameXP and Mp4 Video 1 Click for Home windows are the nice pair for both handbook-accurate and automatic-fast audio conversions. We researched and evaluated 15 audio converter software options that vary in value from free to $39 - narrowing that listing all the way down to one of the best selections available. We examined the conversion pace and ease of use for every converter, and examined every unit's features. We consider Swap Plus Edition is the best audio converter for most people as a result of it has all the main import and export formats, and it could actually convert quicker than any software we examined. If it's essential to convert numerous recordsdata rapidly, that is the best choice. As for decompression pace, it seems from the wavpack documentation that the -x swap will produce recordsdata that decompress sooner in the same manner as FLAC files (albeit at the cost of much slower compression, rendering the two formats a virtual tie). I have not experimented with that switch, nevertheless, so perhaps I misinterpret that. WMA, OGG, FLAC, WAV. All2MP3 convert essentially the most used audio and video formats on to MP3. Free WV to FLAC Converter On-line device which is offered right here helps with conversion of WV to FLAC less consumption of to FLAC file Converter here would not require any of customers e mail signup and personal data. I did notice it took a very long time for dynamic break up to course of a drum monitor using Wavpack in a recent project, so I am going to do as you really helpful and use wav for recording and modifying and only encode to wavpack after a project is completed. All that labored, was deleting the flac files I have sacrificed. My understanding is that the WAV and FLAC codecs are containers for lossless audio. I have seen the FLAC format as being perhaps higher as a result of it is able to losslessly compress audio from say a WAV file. audiokonverter can convert audio information from Ogg, MP3, AAC, M4A, FLAC, WMA, RealAudio, Musepack, Wavpack, WAV, and movies into MP3, Ogg, FLAC, or M4A for iPods. When audiokonverter is changing audio files you see the progress in a terminal window, as proven in the screenshot. To FLAC Converter can encode the limitless number of media recordsdata and folders. Simply add your audio and video for conversion. The application will keep folders' construction, unique tags and file names for all output MP3s. You will be provided with detailed progress of every file's conversion and notified when encoding of all information is finished. Batch Convert imagine having a mp3 converter which could convert FLAC to mp3 with one click on deciding on the whole music tree? Batch Converter can, and with superior file naming rules the converted mp3 information are named simply as you need. Versatile instrument which is compatible with almost all units and can even convert any media file into any device supported format. In addition to changing single audio information into other formats in bulk, you can join multiple files into one larger audio recordsdata with Freemake Audio Converter. You may also regulate the output high quality before changing recordsdata. Free WavPack To MP3 Converter's user-friendliness is mainly due to the straight-ahead interface that it supplies you with, because of which you can swiftly add your files in two mouse moves, wv to flac converter free windows 10 then output them to the targeted format. CUERipper is an utility for extracting digital audio from CDs, an open supply different to EAC. It has so much fewer configuration options, so is somewhat simpler to use, and is included in CUETools package. It supports MusicBrainz and freeDB metadata databases, AccurateRip and CTDB. After loading one or more audio recordsdata to , you simply want to decide on one of many output codecs from under. When the file is able to be downloaded, use the small download button to save it to your pc.

Free download the highly effective wv to flac converter free windows 10 Converter - iDealshare VideoGo ( for Home windows , for Mac ), set up and fireplace up, the following interface will pop up. MP3 converter and audio converter that helps 15 audio formats and 10 video codecs. Convert FLAC to MP3, M4A to MP3, AAC to MP3, WAV to MP3, MP3 to WAV, OGG to MP3, MP3 to FLAC, wv to flac converter free windows 10 MP4 to MP3, Video to MP3. Can someone please assist me convert awv andcue file set I have into individual FLAC tracks? I believed I had this worked out with Foobar, however despite the fact that the ensuing information have been playable, Foobar stated that there were "major errors" within the conversion.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wv To Mp3 Converter,WavePack To Mp3,wv Converter,wv Audio Converter,wv Mp3 Converter

To use the WV conversion function merely add the files you wish to convert to WV. Then click combo-box to choose "WV" as the output format. Excellent app when it's essential to handle enter and output audio information of assorted formats. Many of them indicate numerous settings. The drawback, you can not carry out the conversion in a fast and automated manner. For that goal, I exploit Mp4 Video 1 Click for Windows (search here or google) in conjunction with LameXP. So, being joined collectively, LameXP and Mp4 Video 1 Click on for Windows are the nice pair for each handbook-accurate and automated-fast audio conversions. Say I have a lossy MP3 audio file (5.17Mb, 87% compressed from its original, supply unknown). I then encode it to another lossless format, say FLAC or WAVPACK. Navigate to your WAV file that you just want to convert to MP3 and press the Open button. Right-click on transformed item and choose "Play Destination" to play the destination file, select "Browse Vacation spot Folder" to open Windows Explorer to browse the vacation spot file. 2.Codecs Supported: SPX(Speex),MP3,WMA,MP2,OGG,WAV,AAC(used by iTunes),FLAC, APE,wv,MPC (MusePack),WV(WavePack),OptimFROG, TTA ,Ra(Real audio). TAudioConverter Transportable is packaged in a Installer so it'll routinely detect an existing set up when your drive is plugged in. It helps upgrades by installing proper over an present copy, preserving all settings. And it is in Format, so it routinely works with the Platform including the Menu and Backup Utility. WMA, OGG, FLAC, WAV. All2MP3 convert the most used audio and video codecs on to MP3. Free WV to FLAC Converter On-line instrument which is provided here helps with conversion of wv to flac converter with Crack to FLAC much less consumption of to FLAC file Converter here doesn't require any of users e-mail signup and personal information. I did notice it took a very very long time for dynamic split to course of a drum track using Wavpack in a recent venture, so I'll do as you recommended and use wav for recording and enhancing and only encode to wavpack after a project is finished. If you might want to, you may select an alternate output high quality, frequency, and bitrate from the superior choices. It might probably show you how to convert TS, MTS, M2TS, TRP, TP, WMV, ASF, MKV, AVI, FLV, SWF, and F4V to MP4, MOV, M4V and audio formats like MP3, MP2, WMA, AC3, AIFF, ALAC, WAV, M4A, OGG, and so on. Compress FLAC recordsdata to smaller measurement with out losing any high quality. Right here you can learn how to take a look at efficiency of audio formats by yourself utilizing fmedia. I do not connect any sound information right here, it's higher in the event you use your personal information, most likely in different music genre. Should you wish to share your outcomes with others, please send me a message and I'll do my best to edit the article so it reflects all difference in take a look at results. We solely examined audio converter software that was suitable with the most popular video codecs. Nonetheless, when you plan to use conversion software program primarily for converting video information and sometimes for changing audio, buy a video converter software program as an alternative. In addition to video format compatibility, the best video converter packages are additionally suitable with most the popular audio formats. Listed here are a couple of our favorites. In addition to changing single audio recordsdata into other formats in bulk, you possibly can join multiple information into one bigger audio recordsdata with Freemake Audio Converter. You may also regulate the output quality earlier than converting information. Free WavPack To MP3 Converter's user-friendliness is especially because of the straight-ahead interface that it offers you with, thanks to which you'll be able to swiftly add your recordsdata in two mouse strikes, then output them to the focused format. CUERipper is an utility for extracting digital audio from CDs, an open source various to EAC. It has rather a lot fewer configuration choices, so is considerably simpler to use, and is included in CUETools package deal. It supports MusicBrainz and freeDB metadata databases, AccurateRip and CTDB. After loading a number of audio files to , you just want to decide on one of the output formats from beneath. When the file is ready to be downloaded, use the small obtain button to put it aside to your pc.

Free download the highly effective WV Converter - iDealshare VideoGo ( for Home windows , for Mac ), set up and fireplace up, the following interface will pop up. MP3 converter and audio converter that helps 15 audio formats and wv to flac converter with crack 10 video formats. Convert FLAC to MP3, M4A to MP3, AAC to MP3, WAV to MP3, MP3 to WAV, OGG to MP3, MP3 to FLAC, MP4 to MP3, Video to MP3. Can someone please help me convert awv andcue file set I've into individual FLAC tracks? I thought I had this labored out with Foobar, however although the ensuing files were playable, Foobar said that there were "major errors" within the conversion.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How To Convert APE Recordsdata To MP3

I simply lately wanted to convert some audio recordsdata kind a shopper intoflac format. I wrote the following script for my comfort. To use it - cd to a directory with one pair of matching ape and cue files. The last thing it's best to know is that it's not advisable to convert between lossy formats as you will continue to loss high quality. It's OKAY, nevertheless, to convert between lossless formats as the standard is retained. On Linux, you could possibly use mac to dump theape intowav, then bchunk to separate the bigwav file into tracks utilizing data from thecue file. Click on the HUGE ROUND button on the proper bottom aspect to finish the APE to FLAC conversion with excessive audio high quality and quick pace. I did attempt to convert utilizing JRiver, but the way the information end up you have to highlight every monitor ape to flac converter free download online to delete individually. Doesn't look like a giant deal, but after doing 5 cd's and having three of them copy the highlight instead of delete I gave up. I know that is both user error or finicky keyboard however both manner huge quantities of work versus dbpoweramp that when transformed retains the unique ape files highlighted for simple elimination. As for converting originally didn't know and it was all completed. I wrote Monkey's Audio because again then there was no option to store issues in a lossless approach that allowed real-time playback and tagging. So APE stuffed a hole and was a whole lot of enjoyable to write. Minimal IDTE is an excellent minimalistic, tremendous mild, super moveable version of IDTE-ID3 Tag Editor and is designed to fulfill the requirement of minimal useful resource consumption. Main Venture - Please do not use this challenge for Tagging WAV & MP4 information. As, on account of changed specifications they don't seem to be supported anymore. Some music file types, including WAV (.wav), AIFF (.aiff), and RA (.r) can't be uploaded to your library utilizing Music Supervisor or Google Play Music for Chrome. Have plenty of lengthy podcasts, music, songs in MP3, WAV, APE or FLAC and need to split or minimize them into shorter tracks? If your audio file have a CUE related to it, splitting your music recordsdata can be much simpler by the assistance of the smart Bigasoft CUE plitter for Mac. When you could have accomplished the correct output settings, http://www.audio-transcoder.com/how-to-convert-ape-files-to-flac now you can click on on Convert All button and Wondershare Video Converter Ultimate will begin converting MP3 to FLAC convert the file instantly. Please observe the steps to convert audio information to APE with PowerISO. Subsequent, click on Configure Encoder to alter the settings for the LAME MP3 encoder. By default, it is going to be set to Standard, Quick, which doesn't offer you a really top quality MP3 file. You possibly can convert APE to Apple Lossless with Avdshare Audio Converter. I'm fairly sure you aren't alone in your confusion in regards to the distinction of APE and FLAC. Though APE (Monkey's Audio) and FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec) are lossless audio compression codecs, they have their very own traits for different usage. Therefore, you might as nicely have a look on the APE vs FLAC comparability in your reference. iSkysoft iMedia Converter Deluxe provides an possibility to avoid wasting to presets supported by totally different cell units, media players, and gaming consoles. During the conversion course of, you possibly can select the output format relying in your system kind. The device might be an iOS or an Android telephone. Added assist of format FLAC. And it stays like this for all future use of the MP3 format, until one goes to Tools""Preferences""Reset preferences" which then returns all to defaults and it really works, however solely on the 128 bit rate. Different formats like OGG Vorbis and many others usually are not showing this behaviour, and I do not bear in mind my earlier verson which was 2.zero.5., doing this. While iPhones and iPads are engaging, well-designed gadgets, they do come with strict limitations with regards to the type of audio files they will accept — Apple isn't recognized for taking part in nice with recordsdata, besides these the company sells you. It may be irritating to drop thousands on high-finish hardware, only to be limited by the Apple ecosystem. four.Audio cutter utility lets you trim your flac music files to take away silence, or undesirable sections. When your music recordsdata are added, use the mouse to pick all the music files or press Ctrl+A on Home windows PC or Command+A on Mac laptop. For the ultimate 12 years I've been listening to only 320mp3s and every time I come accross flac or CDs, I truly do not hear sufficient of a difference to alter every thing to flac. It has a bonus over MP3, although, in that it'll in all probability achieve better sound high quality with the same file dimension or smaller. FLAC is a lossless audio format. There are a restricted variety of media players that assist this, too. Click OKAY a few times to get back to the principle display screen after which click on the Play button at top to start the encoding course of. In my example, I converted a 6 min 45 sec sixty eight MB WAV file to a 12 MB 256 kbps MP3 file utilizing this program. For those who go with the default settings, you will get a four MB MP3 file. Ultimately, we advise converting your audio to MP3 or AAC as a result of enormous quantity of compatibility with different products, and if encoded using a excessive bit-cost the usual could be nearly an similar to a lossless format. FLAC is usually a great selection because of it may maintain your audio in a lossess format from which you will convert from in the future. If you happen to happen to're altering reel to reel to CD , or audio cassette to CD , these information shall be uncompressed WAV information after transferring, and will be reworked to any format mentioned above.

Moving on, however, I have installed soundKonverter as properly, and that also says that it helps ape out of the box, but when browse to a folder of ape files, soundKonverter can not open them. I've tried dragging the folder, opening just recordsdata and so forth. No luck. Hi-fi: After all, the most important benefit to FLAC recordsdata is that they are ideally suited to listening on a hello-fi system. In the previous couple of years, a wealth of streaming audio gamers have appeared with lossless FLAC playback one among their many advantages. The least costly of those is the $35, £30 or AU$fifty nine Chromecast Audio however these multiroom music programs also support the format.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Complete Guide to the Fakaza mp3 Songs for Latest Music Release

Ongoing music from an assist with preferring Spotify or Apple Music is mind blowing, yet altogether it's not worthwhile constantly. For example, you'll require a solid web affiliation. Also, remembering that you can download tunes for disengaged play, when you quit paying the month to month charge, permission to your music disappears.

Buying electronic music, for instance, MP3s or FLAC Latest amapiano songs appears to be OK in light of multiple factors. The tracks are on the whole yours and put on anything device you want, and it better finances the skilled worker who can then keep on making more music. These stores offer lossy music records accessible to be bought, but most also offer lossless FLAC or ALAC for a detectable extension in quality, and they commonly cost comparable to MP3.

Whether you're wanting to buy a music single or whole assortments, here are the best objections to visit. Most recent music Mp3 I'll start with the serious deal - - iTunes and Amazon - - and forge ahead toward a piece of my top decisions that you probably won't have known about, including Bandcamp.

Why Streaming isn't Enough and how Fakaza mp3 Songs are the Future of Music Consumption?

The destiny of music will likely seek after comparative bearings we are finding in current advancement. It will be incomprehensibly well disposed like virtual amusement, it will end up being continuously PC based and A.I.

Music streaming has disturbed the music business and immediately changed how clients focus on and purchase music. Music online highlights offer many tunes from an enormous number of experts for a monotonous cost consistently, allowing clients to get to music at a significantly less costly rate than currently possible.

MP3s versus Streaming

Notable streaming destinations like Spotify and Pandora usually use a bitrate of 160 kbps, which isn't actually that of MP3s. Accepting you spring for Spotify Premium, you'll anyway approach 320 kbps tracks, which is indistinguishable from MP3s. Streaming is one of the vitally streaming destinations that streams in CD quality.

The fundamental way entertainers acquire cash online is from mechanical and streaming sways. That is a lavish way to deal with communicating pay from online arrangements through stages like iTunes as well as streaming compensation from Spotify and various organizations.

Instructions to Shop for the Latest Music Albums and Fakaza mp3 Songs Format Online

How should I buy MP3 tunes? No matter what the climb of streaming, a large number of MP3s are at this point prepared to move and the amount of tracks is growing continually. All of the stores recorded here enable you to either download tunes legally to a PC or clearly to your phone - - and most recommendation gave applications for Android.

Though online music organizations are extensive nowadays, you can Latest amapiano songs regardless purchase music singles and assortments. Whether you slant toward the solace of cutting edge plans, the energy and elegant vinyl, or the nostalgic worth of CDs, crowd individuals can regardless have their main tunes.

Pay attention To Your Favorite Songs and Albums in HQ Audio Quality With These Mp 3 Sites

While streaming objections, for instance, Pandora might be favorable for an in a rush music experience, where do you go when you really want to hear music as the specialist arranged? Focusing on unrecorded music is one strategy for doing that, but unfortunately we can't put every one of our #1 specialists in our pocket for little engaging gatherings. Most recent South African tunes That is where Hi-Res Audio turns out to be perhaps the main element.

Hello res sound annihilates MP3s and AAC records. Principal data is lost when you focus on music through MP3 records considering the lossy tension that makes these reports more humble. High-Resolution Audio can imitate the whole extent of sound that the skilled worker made while recording the substance. Sony understands the meaning of defending the inventiveness of music, which is the explanation we've made Hi-Res Audio things that grant audiophiles (like you) to focus on music in the best strong quality.

So where might you anytime at some point find Hi-Res Audio tunes that the audiophile in you yearns for? Explore our Top 5 picks for Hi-Res Audio downloading destinations under.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Renault Sandero Driver’s Review

The new Renault Sandero is armed with fresh styling and plenty of standard specification.

With a turbocharged 898 cm3 unit delivering 66 kW and 135 N.m of torque, I expected there to be a little more oomph, but I soon discovered that I needed to make good use of the Sandero’s rev range and five-speed manual ‘box to get it to feel as zippy as I would like it to be, which is weird for a forced-induced car. This, I suspect, will impact on fuel consumption - an area that turbocharged units are supposed to thrive in. Renault claims a consumption of 5,2 litres/100 km. The Sandero’s ride is slightly firm as a result of the 15-inch wheels, but it’s not uncomfortable. It’s also a very settled vehicle thanks to the standard fitment of a stability control system in both the Expression and Dynamique models.

The 20-something-year-old side of me (we shall name her Fun Kelly) that has little money and places a lot of value in well, value for money and how much nice stuff (as I would say were I chatting to my friends) I could get for my hard-earned cash, doesn’t always look at engine offering and ride quality first though. What this side of me immediately considers is how many people can I fit in the vehicle with relative comfort, would there be space for all our luggage should we want to road trip, how can I play my tunes to sing along to and how comfortable is the car as a living space.

In terms of people-carrying abilities and luggage space, the Sandero offers a decent amount of both. The rear bench is able to house three passengers and offers ample legroom for all. Renault claims that the boot can swallow 292 dm3 of luggage - more than its closest competitors that offer 270 dm3 in the case of the Volkswagen Polo Vivo, 251 dm3 for the Toyota Etios and 284 dm3 for the Ford Figo. When it comes to music, the Sandero offers an MP3-compatible audio system that can play CDs or be connected via USB or Bluetooth. There’s also the befit of satellite audio controls behind the steering wheel. On a comfort level, there’s cruise control and air-conditioning (available as an option on the Expression) in the high-spec Dynamique model, while both come fitted with central locking, a height-adjustable steering column, and safety features that include ABD with EBD and brake assist and dual front air bags (with side airbags available on the Dynamique).

We also have to consider the fact that this is a Renault and that while it’s an excellent value proposition straight off the showroom floor, there’s always that part of my mind wondering what the aftersales experience would be like. Let’s be honest, it faces stiff competition, all of which come with relatively good after-sale support and wide dealer networks, and two of which are locally made, so parts should be easier to come by.

Then we’re swayed by the fact that, even though the dealer network isn’t as big as the others' and even though servicing comes courtesy of a multi-franchise, Renault SA has given this vehicle a standard 2-year/30 000 km service plan and a 5-year/150 000 km warranty. Of its competitors, only the Etios has a service plan to match that of the Sandero’s.

With all that it offers as standard, the Sandero is a bargain. The verdict is this: the engine isn't quite up to scratch and, therefore, the engine may need to be worked a bit harder than one would like, but I can’t deny that it’s good value-for-money. There aren’t any cars at this end of the market that can offer all that the Sandero offers. It's a very tempting buy among a crowd that offers rather basic specification. If you can live with an engine that underperforms slightly, the Sandero is definitely worth a look.

*Specifications:

Model: Renault Sandero

Engine: 898 cm3, three-cylinder turbopetrol

Transmission: five-speed manual

Power: 66 kW @ 5 280 r/min

Torque: 135 N.m @ 2 500 r/min

0-100 km/h: 11,1 secs

Fuel consumption: 5,2 litres/100 km

CO2: 119 g/km

Luggage capacity: 290 dm3

Service plan: 2 years/30 000 km

Service intervals: 15 000 km

*According to Renault

Article sourced from: https://www.carmag.co.za/

0 notes

Text

You, an intellectual: With the prevalence of streaming sites like Spotify and the DRM attendant usurping more traditional forms of media consumption like CDs, most people no longer hold true ownership of the media they enjoy, and will suffer

Me, a caveman technologically stuck in the 2000s who still uses iTunes and YouTube-to-mp3 converters and burns music from my local library’s CD collection by the armload: lmao can’t relate

#No. YOU don't own the music you consume. I have complete possession of all the music I've acquired through legally dubious means#.txt#but I'm also willing to download full albums off YouTube then separate them into individual tracks in Audacity#and I like a lot of obscure music you can't find on mainstream sites like Spotify#so

0 notes

Text

sauntering-vaguely-downwards replied to your post: I love the fact that libraries are doing more...

we also have music streaming sites and language learning apps and apparently my particular library has a youtube channel for some un-fucking-known reason

hahaha yeah idk if mine has those (it’s rather small) but tbh I’m happy I don’t have to go through the trouble of ripping CDs anymore because I can just. copy the mp3 files

I haven’t found where their shitty ass app (that used to be better but they wanted me to update it so instead of having a proper program I have an app and I have failed at every attempt to download the proper program again) stores the EPUB files when it downloads them so it’s harder to copy ebooks for personal consumption, but my mom doesn’t use her kindle much since she got a smart phone so it’s not too annoying for her to leave the wifi off

ANYWAY the point is I love libraries and I haven’t seen my fav librarians this summer (I know one moved to a different branch bc her landlord was shitty and she moved in with her bf and got a pay raise and I’m happy for her even though I miss her) and tbh I’m kind of bummed about that

#sauntering-vaguely-downwards#larkie has friends#one time they had to close the library due to a sudden snow storm#and my mom took forever to come bc it was a whiteout#and so it was just me and the librarians in this closed and darkened library#another time this guy was an asshat to me and a friend during some presentation#and the librarians like took care of us afterwards and had some Words with him#last time I was there I had a long talk with one of them about like types of vodka#these ladies are basically an extra group of moms for me and I miss them

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Man Who Broke the Music Business

One Saturday in 1994, Bennie Lydell Glover, a temporary employee at the PolyGram compact-disk manufacturing plant in Kings Mountain, North Carolina, went to a party at the house of a co-worker. He was angling for a permanent position, and the party was a chance to network with his managers. Late in the evening, the host put on music to get people dancing. Glover, a fixture at clubs in Charlotte, an hour away, had never heard any of the songs before, even though many of them were by artists whose work he enjoyed.

Later, Glover realized that the host had been d.j.’ing with music that had been smuggled out of the plant. He was surprised. Plant policy required all permanent employees to sign a “No Theft Tolerated” agreement. He knew that the plant managers were concerned about leaking, and he’d heard of employees being arrested for embezzling inventory. But at the party, even in front of the supervisors, it seemed clear that the disks had been getting out. In time, Glover became aware of a far-reaching underground trade in pre-release disks. “We’d run them in the plant in the week, and they’d have them in the flea markets on the weekend,” he said. “It was a real leaky plant.”

The factory sat on a hundred acres of woodland and had more than three hundred thousand square feet of floor space. It ran shifts around the clock, every day of the year. New albums were released in record stores on Tuesdays, but they needed to be pressed, packaged, and shrink-wrapped weeks in advance. On a busy day, the plant produced a quarter of a million CDs. Its lineage was distinguished: PolyGram was a division of the Dutch consumer-electronics giant Philips, the co-inventor of the CD.

One of Glover’s co-workers was Tony Dockery, another temporary hire. The two worked opposite ends of the shrink-wrapping machine, twelve feet apart. Glover was a “dropper”: he fed the packaged disks into the machine. Dockery was a “boxer”: he took the shrink-wrapped jewel cases and stacked them in a cardboard box for shipping. The jobs paid about ten dollars an hour.

Glover and Dockery soon became friends. They lived in the same town, Shelby, and Glover started giving Dockery a ride to work. They liked the same music. They made the same money. Most important, they were both fascinated by computers, an unusual interest for two working-class Carolinians in the early nineties—the average Shelbyite was more likely to own a hunting rifle than a PC. Glover’s father had been a mechanic, and his grandfather, a farmer, had moonlighted as a television repairman. In 1989, when Glover was fifteen, he went to Sears and bought his first computer: a twenty-three-hundred-dollar PC clone with a one-color monitor. His mother co-signed as the guarantor on the layaway plan. Tinkering with the machine, Glover developed an expertise in hardware assembly, and began to earn money fixing the computers of his friends and neighbors.

By the time of the party, he’d begun to experiment with the nascent culture of the Internet, exploring bulletin-board systems and America Online. Soon, Glover also purchased a CD burner, one of the first produced for home consumers. It cost around six hundred dollars. He began to make mixtapes of the music he already owned, and sold them to friends. “There was a lot of people down my way selling shoes, pocketbooks, CDs, movies, and fencing stolen stuff,” he told me. “I didn’t think they’d ever look at me for what I was doing.” But the burner took forty minutes to make a single copy, and business was slow.

Glover began to consider selling leaked CDs from the plant. He knew a couple of employees who were smuggling them out, and a pre-release album from a hot artist, copied to a blank disk, would be valuable. (Indeed, recording executives at the time saw this as a key business risk.) But PolyGram’s offerings just weren’t that good. The company had a dominant position in adult contemporary, but the kind of people who bought knockoff CDs from the trunk of a car didn’t want Bryan Adams and Sheryl Crow. They wanted Jay Z, and the plant didn’t have it.

By 1996, Glover, who went by Dell, had a permanent job at the plant, with higher pay, benefits, and the possibility of more overtime. He began working double shifts, volunteering for every available slot. “We wouldn’t allow him to work more than six consecutive days,” Robert Buchanan, one of his former managers, said. “But he would try.”

The overtime earnings funded new purchases. In the fall of 1996, Hughes Network Systems introduced the country’s first consumer-grade broadband satellite Internet access. Glover and Dockery signed up immediately. The service offered download speeds of up to four hundred kilobits per second, seven times that of even the best dial-up modem.

Glover left AOL behind. He soon found that the real action was in the chat rooms. Internet Relay Chat networks tended to be noncommercial, hosted by universities and private individuals and not answerable to corporate standards of online conduct. You created a username and joined a channel, indicated by a pound sign: #politics, #sex, #computers. Glover and Dockery became chat addicts; sometimes, even after spending the entire day together, they hung out in the same chat channel after work. On IRC, Dockery was St. James, or, sometimes, Jah Jah. And Glover was ADEG, or, less frequently, Darkman. Glover did not have a passport and hardly ever left the South, but IRC gave him the opportunity to interact with strangers from all over the world.

Also, he could share files. Online, pirated media files were known as “warez,” from “software,” and were distributed through a subculture dating back to at least 1980, which called itself the Warez Scene. The Scene was organized in loosely affiliated digital crews, which raced one another to be the first to put new material on the IRC channel. Software was often available on the same day that it was officially released. Sometimes it was even possible, by hacking company servers, or through an employee, to pirate a piece of software before it was available in stores. The ability to regularly source pre-release leaks earned one the ultimate accolade in digital piracy: to be among the “elite.”

By the mid-nineties, the Scene had moved beyond software piracy into magazines, pornography, pictures, and even fonts. In 1996, a Scene member with the screen name NetFraCk started a new crew, the world’s first MP3 piracy group: Compress ’Da Audio, or CDA, which used the newly available MP3 standard, a format that could shrink music files by more than ninety per cent. On August 10, 1996, CDA released to IRC the Scene’s first “officially” pirated MP3: “Until It Sleeps,” by Metallica. Within weeks, there were numerous rival crews and thousands of pirated songs.

Glover’s first visit to an MP3-trading chat channel came shortly afterward. He wasn’t sure what an MP3 was or who was making the files. He simply downloaded software for an MP3 player, and put in requests for the bots of the channel to serve him files. A few minutes later, he had a small library of songs on his hard drive.

One of the songs was Tupac Shakur’s “California Love,” the hit single that had become inescapable after Tupac’s death, several weeks earlier, in September, 1996. Glover loved Tupac, and when his album “All Eyez on Me” came through the PolyGram plant, in a special distribution deal with Interscope Records, he had even shrink-wrapped some of the disks. Now he played the MP3 of “California Love.” Roger Troutman’s talk-box intro came rattling through his computer speakers, followed by Dr. Dre’s looped reworking of the piano hook from Joe Cocker’s “Woman to Woman.” Then came Tupac’s voice, compressed and digitized from beyond the grave, sounding exactly as it did on the CD.

At work, Glover manufactured CDs for mass consumption. At home, he had spent more than two thousand dollars on burners and other hardware to produce them individually. His livelihood depended on continued demand for the product. But Glover had to wonder: if the MP3 could reproduce Tupac at one-eleventh the bandwidth, and if Tupac could then be distributed, free, on the Internet, what the hell was the point of a compact disk?

In 1998, Seagram Company announced that it was purchasing PolyGram from Philips and merging it with the Universal Music Group. The deal comprised the global pressing and distribution network, including the Kings Mountain plant. The employees were nervous, but management told them not to worry; the plant wasn’t shutting down—it was expanding. The music industry was enjoying a period of unmatched profitability, charging more than fourteen dollars for a CD that cost less than two dollars to manufacture. The executives at Universal thought that this state of affairs was likely to continue. In the prospectus that they filed for the PolyGram acquisition, they did not mention the MP3 among the anticipated threats to the business.

The production lines were upgraded to manufacture half a million CDs a day. There were more shifts, more overtime hours, and more music. Universal, it seemed, had cornered the market on rap. Jay Z, Eminem, Dr. Dre, Cash Money—Glover packaged the albums himself.

Six months after the merger, Shawn Fanning, an eighteen-year-old college dropout from Northeastern University, débuted a public file-sharing platform he had invented called Napster. Fanning had spent his adolescence in the same IRC underground as Glover and Dockery, and was struck by the inefficiency of its distribution methods. Napster replaced IRC bots with a centralized “peer-to-peer” server that allowed people to swap files directly. Within a year, the service had ten million users.

Before Napster, a leaked album had caused only localized damage. Now it was a catastrophe. Universal rolled out its albums with heavy promotion and expensive marketing blitzes: videos, radio spots, television campaigns, and appearances on late-night TV. The availability of pre-release music on the Internet interfered with this schedule, upsetting months of work by publicity teams and leaving the artists feeling betrayed.

Even before Napster’s launch, the plant had begun to implement a new anti-theft regimen. Steve Van Buren, who managed security at the plant, had been pushing for better safeguards since before the Universal merger, and he now instituted a system of randomized searches. Each employee was required to swipe a magnetized identification card upon leaving the plant. Most of the time, a green light appeared and the employee could leave. Occasionally, though, the card triggered a red light, and the employee was made to stand in place as a security guard ran a wand over his body, searching for the thin aluminum coating of a compact disk.

Van Buren succeeded in getting some of the flea-market bootleggers shut down. Plant management had heard of the technician who had been d.j.’ing parties with pre-release music, and Van Buren requested that he take a lie-detector test. The technician failed, and was fired. Even so, Glover’s contacts at the plant could still reliably get leaked albums. One had even sneaked out an entire manufacturing spindle of three hundred disks, and was selling them for five dollars each. But this was an exclusive trade, and only select employees knew who was engaged in it.

By this time, Glover had built a tower of seven CD burners, which stood next to his computer. He could produce about thirty copies an hour, which made bootlegging more profitable, so he scoured the other underground warez networks for material to sell: PlayStation games, PC applications, MP3 files—anything that could be burned to a disk and sold for a few dollars.

He focussed especially on movies, which fetched five dollars each. New compression technology could shrink a feature film to fit on a single CD. The video quality was poor, but business was brisk, and soon he was buying blank CDs in bulk. He bought a label printer to catalogue his product, and a color printer to make mockups of movie posters. He filled a black nylon binder with images of the posters, and used it as a sales catalogue. He kept his inventory in the trunk of his Jeep and sold the movies out of his car.

Glover still considered it too risky to sell leaked CDs from the plant. Nevertheless, he enjoyed keeping up with current music, and the smugglers welcomed him as a customer. He was a permanent employee with no rap sheet and an interest in technology, but outside the plant he had a reputation as a roughrider. He owned a Japanese street-racing motorcycle, which he took to Black Bike Week, in Myrtle Beach. He had owned several handguns, and on his forearm was a tattoo of the Grim Reaper, walking a pit bull on a chain.

His co-worker Dockery, by contrast, was a clean-cut churchgoer, and too square for the smugglers. But he had started bootlegging, too, and he pestered Glover to supply him with leaked CDs. In addition, Dockery kept finding files online that Glover couldn’t: movies that were still in theatres, PlayStation games that weren’t scheduled to be released for months.

For a while, Glover traded leaked disks for Dockery’s software and movies. But eventually he grew tired of acting as Dockery’s courier, and asked why the disks were so valuable. Dockery invited him to his house one night, where he outlined the basics of the warez underworld. For the past year or so, he’d been uploading the pre-release leaks Glover gave him to a shadowy network of online enthusiasts. This was the Scene, and Dockery, on IRC, had joined one of its most élite groups: Rabid Neurosis, or RNS. (Dockery declined to comment for this story.)

Instead of pirating individual songs, RNS was pirating entire albums, bringing the pre-release mentality from software to music. The goal was to beat the official release date whenever possible, and that meant a campaign of infiltration against the major labels.

The leader of RNS went by the handle Kali. He was a master of surveillance and infiltration, the Karla of music piracy. It seemed that he spent hours each week researching the confusing web of corporate acquisitions and pressing agreements that determined where and when CDs would be manufactured. With this information, he built a network of moles who, in the next eight years, managed to burrow into the supply chains of every major music label. “This stuff had to be his life, because he knew about all the release dates,” Glover said.

Dockery—known to Kali as St. James—was his first big break. According to court documents, Dockery encountered several members of RNS in a chat room, including Kali. Here he learned of the group’s desire for pre-release tracks. He soon joined RNS and became one of its best sources. But, when his family life began to interfere, he proposed that Glover take his place.

Glover hesitated: what was in it for him?

He learned that Kali was a gatekeeper to the secret “topsite” servers that formed the backbone of the Scene. The ultra-fast servers contained the best pirated media of every form. The Scene’s servers were well hidden, and log-ons were permitted only from pre-approved Internet addresses. The Scene controlled its inventory as tightly as Universal did—maybe tighter.

If Glover was willing to upload smuggled CDs from the plant to Kali, he’d be given access to these topsites, and he’d never have to pay for media again. He could hear the new Outkast album weeks before anyone else did. He could play Madden NFL on his PlayStation a month before it became available in stores. And he could get the same movies that had allowed Dockery to beat him as a bootlegger.

Dockery arranged a chat-room session for Glover and Kali, and the two exchanged cell-phone numbers. In their first call, Glover mostly just listened. Kali spoke animatedly, in a patois of geekspeak, California mellow, and slang borrowed from West Coast rap. He loved computers, but he also loved hip-hop, and he knew all the beefs, all the disses, and all the details of the feuds among artists on different labels. He also knew that, in the aftermath of the murders of Tupac and the Notorious B.I.G., those feuds were dying down. Def Jam, Cash Money, and Interscope had all signed distribution deals with Universal. Kali’s research kept taking him back to the Kings Mountain plant.

He and Glover hashed out the details of their partnership. Kali would track the release dates of upcoming albums and tell Glover which material he was interested in. Glover would acquire smuggled CDs from the plant. He would then rip the leaked CDs to the MP3 format and, using encrypted channels, send them to Kali’s home computer. Kali packaged the MP3s according to the Scene’s exacting technical standards and released them to its topsites.

The deal sounded good to Glover, but to fulfill Kali’s requests he’d have to get new albums from the plant much more frequently, three or four times a week. This would be difficult. In addition to the randomized search gantlet, a fence had been erected around the parking lot. Emergency exits set off alarms. Laptop computers were forbidden in the plant, as were stereos, portable players, boom boxes, and anything else that might accept and read a CD.

Every once in a while, a marquee release would come through—“The Eminem Show,” say, or Nelly’s “Country Grammar.” It arrived in a limousine with tinted windows, carried from the production studio in a briefcase by a courier who never let the master tape out of his sight. When one of these albums was pressed, Van Buren ordered wandings for every employee in the plant.

The CD-pressing machines were digitally controlled, and they generated error-proof records of their output. The shrink-wrapped disks were logged with an automated bar-code scanner. The plant’s management generated a report, tracking which CDs had been printed and which had actually shipped, and any discrepancy had to be accounted for. The plant might now press more than half a million copies of a popular album in a day, but the inventory could be tracked at the level of the individual disk.

Employees like Glover, who worked on the packaging line, had the upper hand when it came to smuggling CDs. Farther down the line and the disks would be bar-coded and logged in inventory; farther up and they wouldn’t have access to the final product. By this time, the packaging line was becoming increasingly complex. The chief advantage of the compact disk over the MP3 was the satisfaction of owning a physical object. Universal was really selling packaging. Album art had become ornate. The disks were gold or fluorescent, the jewel cases were opaque blue or purple, and the album sleeves were thick booklets printed on high-quality paper. Dozens, sometimes hundreds, of extra disks were now being printed for every run, to be used as replacements in case any were damaged during packaging.

At the end of each shift, employees put the overstock disks into scrap bins. These scrap bins were later taken to a plastics grinder, where the disks were destroyed. Over the years, Glover had dumped hundreds of perfectly good disks into the bins, and he knew that the grinder had no memory and generated no records. If there were twenty-four disks and only twenty-three made it into the grinder’s feed slot, no one in accounting would know.

So, on the way from the conveyor belt to the grinder, an employee could take off his surgical glove while holding a disk. He could wrap the glove around the disk and tie it off. He could then hide the disk, leaving everything else to be destroyed. At the end of his shift, he could return and grab the disk.

That still left the security guards. But here, too, there were options. One involved belt buckles. They were the signature fashion accessories of small-town North Carolina. Many people at the plant wore them—big oval medallions with the Stars and Bars on them. Gilt-leaf plates embroidered with fake diamonds that spelled out the word “boss.” Western-themed cowboy buckles with longhorn skulls and gold trim. The buckles always set off the wand, but the guards wouldn’t ask anyone to take them off.

Hide the disk inside the glove; hide the glove inside a machine; retrieve the glove and tuck it into your waistband; cinch your belt so tight it hurts your bladder; position your oversized belt buckle in front of the disk; cross your fingers as you shuffle toward the turnstile; and, if you get flagged, play it very cool when you set off the wand.

From 2001 on, Glover was the world’s leading leaker of pre-release music. He claims that he never smuggled the CDs himself. Instead, he tapped a network of low-paid temporary employees, offering cash or movies for leaked disks. The handoffs took place at gas stations and convenience stores far from the plant. Before long, Glover earned a promotion, which enabled him to schedule the shifts on the packaging line. If a prized release came through the plant, he had the power to ensure that his man was there.

The pattern of label consolidation had led to a stream of hits at Universal’s factory. Weeks before anyone else, Glover had the hottest albums of the year. He ripped the albums on his PC with software that Kali had sent, and then uploaded the files to him. The two made weekly phone calls to schedule the timing of the leaks.