#nonmariners

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Paparazzi was out in full affect yesterday at #nonmariners and caught #0nlyfins in the mix lol👀📸...Definitely an epic day chilling with some real ones 💯🙌🏾🤙🏾. Drone footage credits go to @mykel_bda awesome work bro👊🏾👊🏾👊🏾 https://www.instagram.com/p/CSFz6K_sIoF/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Give me a book and a beach and I'll be ok 👌🏼. Enjoying a few final days in beautiful Bermuda #bermudaful #bermuda #nonmariners #warwicklongbay #fashionillustration #copicmarkers #hnicholsillustration (at Warwick Long Bay)

#copicmarkers#warwicklongbay#bermudaful#bermuda#hnicholsillustration#nonmariners#fashionillustration

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tata project vacancies for marine and highways projects

Tata project vacancies for marine and highways projects

Shankar Anappindi⚫ 2nd Head – Global Talent Acquisition, SBG . Tata Projects has the following opportunities: Location: KARAIKAL (TN) & DIGHI (MH). Mode of employment: Outsourced Interested may leave the following details in the comment box – “Location Interested, eMail ID & Contact No.”. 2 of my team members (Raja for Karaikal & Manas for Dighi) will monitor this page and shall get in touch with…

View On WordPress

#employment#marine#MGH#nonmarine#OGH#oilandgas#oilandgasjobs#opportunities#safetyofficer#( Mechanical#Civil)#electrical#Execution

0 notes

Text

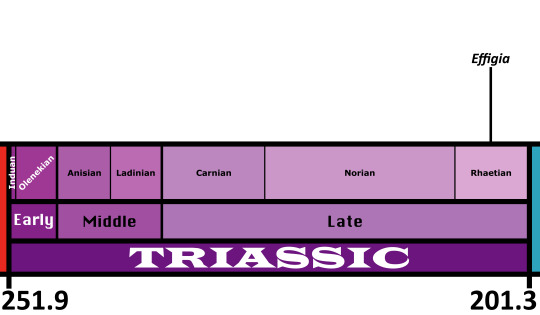

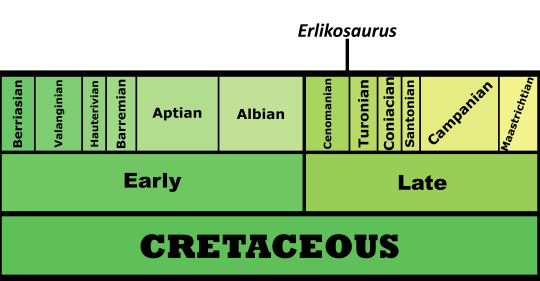

Effigia okeeffeae

By Stolpergeist

Etymology: Ghost

First Described By: Nesbitt and Norell, 2006

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Disapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Archosauria, Pseudosuchia, Suchia, Paracrocodylomorpha, Poposauroidea, Shuvosauridae

Referred Species: E. okeeffeae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Around 205 million years ago, in the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Effigia was found at Ghost Ranch in the Chinle Formation in New Mexico

Physical Description: Effigia was a small, bipedal animal that remarkably resembled dinosaurs it lived with at the time. In total, from head to tail, it would have been about two meters long. It walked on two legs that were held directly underneath the body, and it had small arms that weren’t used in supporting its weight. It had a long body, with a decently sized tail and long neck. The head of Effigia was small and narrow, ending in a beak and having no teeth whatsoever. So, in short, it looked like the later Limusaurus, except it wasn’t feathered - and it wasn’t a dinosaur! This is the first known example of the lightly-built bipedal animal with a beak body plan, aka, the “ostrich” body plan, even though this iteration - the first iteration - had nothing resembling feathers or efficient breathing or hollow bones. In fact, it probably would have breathed primarily based on abdominal muscles, based on its close relatives. And it did have hollow bone walls, much like dinosaurs. Effigia also had a somewhat endothermic body temp - ie, it was closer to warm-bloodedness than modern crocodilians, and may have even been warm-blooded outright. It had five fingers on each hand, though only three of each would have claws; it had four main toes on each foot, unlike the three in theropods, and a little toe raised up (kind of like the fourth toe in theropods). It was rather front heavy, unlike theropods that lean more towards the hip, giving it a forward-leaning appearance.

Diet: Probably herbivorous. While the exact diet of Effigia is murky, the beak of this species indicates it probably would have fed on a variety of plant material, like the later mimics such as Limusaurus and Ornithomimus. However, omnivory was certainly not out of the question.

Behavior: Because Effigia was front-titled, it’s actually not clear whether or not it would have behaved similarly to the animals it resembles. In fact, it doesn’t seem very well adapted for fast movement at all - it looks exactly like the sort of creature that may have tripped over itself on a regular basis. That said, it is entirely possible that it would have balanced itself differently, or adjusted its position in such a way to make up for this oddity in posture. That said, it also had fairly short legs compared to its overall body length, so it’s doubtful that it would have been a fast mover in any position. As such, it probably would have moved slowly throughout its ecosystem, grazing on plants and following fresh vegetation where it came up and utilizing its long neck to reach into areas where food was less accessible, and grabbing on to it for feeding. It may not have been a particularly social animal though, like living archosaurs, it probably would have taken care of its young in some fashion.

Ecosystem: Ghost Ranch was a large floodplain, not quite as forested as the environment had been in earlier times (when they were literally called the “petrified forest”), however, there were still extensive dry forests that experienced dramatic dry and wet seasons each year. These seasons were interspersed with regular flooding, which lead to rapid preservation of a very diverse Late Triassic ecosystem. This was an extremely diverse habitat, with a variety of other reptiles that lived alongside Effigia. There was the slender dinosaur Coelophysis, the weirdly-toothed dinosaur Daemonosaurus, the Silesaurids Kawanasaurus and Eucoelophysis, the Lagerpetid Dromomeron, the early Crocodylomorph Hesperosuchus, the Aetosaur Stenomyti, the phytosaur Redondasaurus, the Drepanosaurs Avicranium and Drepanosaurus, the aquatic archosauriform Vancleavea, the sphenodont Whitakersaurus; coelocanths, ray-finned fish, mystery fish, and even invertebrates such as branchiopods and ostracods. It’s possible that Effigia lived alongside other animals as well, but more research is needed into the exact environment of the Chinle Formation where Effigia was found before that can be confirmed. It is entirely possible that Effigia would have been preyed upon by Coelophysis.

Other: Effigia is so freaking weird, you guys. Like, the Triassic may as well be called the Period in Which Reptiles Tried Out All The Things Dinosaurs Would Later Do (But Only Dinosaurs Would Get Paid For It). It is so similar to later Ornithomimosaurs that at least a few paleontologists used to think that the remains later called Effigia were actually dinosaurs, before their proper reassignment into the Pseudosuchians. This just emphasizes how much different reptiles were trying out new designs and new ideas in the Triassic Period, some of which superficially resembled later dinosaurs - but with surprise twists. It also demonstrates exactly how much crocodile-relatives were diversifying extensively in the Triassic, and how hard they would be hit by the end-Triassic extinction.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Colbert, E. H.. 1947. The little dinosaurs of Ghost Ranch. Natural History 59(9):392-399-427-428.

Heckert, A. B., S. G. Lucas, L. F. Rinehart and A. P. Hunt. 2008. A new genus and species of sphenodontian from the Ghost Ranch Coelophysis Quarry (Upper Triassic: Apachean), Rock Point Formation, New Mexico, USA. Palaeontology 51(4):827-845.

Hunt, A. P., and A. G. Lucas. 1989. Late Triassic vertebrate localities in New Mexico. In S. G. Lucas and A. P. Hunt (eds.), Dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs in the American Southwest, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque 72-101.

Hunt, A. P., and S. G. Lucas. 1993. A new phytosaur (Reptilia: Archosauria) genus from the uppermost Triassic of the western United States and its biochonological significance. In S. G. Lucas and M. Morales (eds.), The Nonmarine Triassic. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 3:193-196.

Lucas, S. G., J. A. Spielmann, A. P. Hunt. 2007. Taxonomy of Shuvosaurus, a Late Triassic archosaur from the Chinle Group, American Southwest. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 41: 259 - 261.

Lucas, S. G., J. A. Spielmann, and L. F. Rinehart. 2013. Juvenile skull of the phytosaur Redondasaurus from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, and phytosaur ontogeny. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 61:389-400.

Martz, J. W., B. J. Small. 2019. Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae). PeerJ 7: e7551.

Nesbitt, S., M. A. Norell. 2006. Extreme convergence in the body plans of an early suchian (Archosauria) and ornithomimid dinosaurs (Theropoda). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (1590): 1045-1048.

Nesbitt, S. 2007. The anatomy of Effigia okeeffeae (Archosauria, Suchia), theropod-like convergence, and the distribution of related taxa. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 302: 84.

Nesbitt, S. J., M. R. Stocker, B. J. Small and A. Downs. 2009. The osteology and relationships of Vancleavea campi (Reptilia: Archosauriformes). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 157:814-864.

Nesbitt, S. 2011. The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 352: 1 - 292.

Pritchard, A. C., and S. J. Nesbitt. 2017. A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida. Royal Society Open Science 4:170499.

Renesto, S., J. A. Spielmann, S. G. Lucas and G. T. Spagnoli. 2010. The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 46:1-81.

Rinehart, L. F., S. G. Lucas, A. B. Heckert, J. A. Spielmann, and M. D. Celeskey. 2009. The paleobiology of Coelophysis bauri (Cope) from the Upper Triassic (Apachean) Whitaker quarry, New Mexico, with detailed analysis of a single quarry block. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 45:1-260.

Schachner, E. R., P. L. Manning, P. Dodson. 2011. Pelvic and hindlimb myology of the basal archosaur Poposaurus gracilis (archosauria: Poposauroidea). Journal of MOrphology 272 (12): 1464 - 1491.

Schaeffer, B. 1967. Late Triassic fishes from the western United States. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 135(6):285-342.

Sues, H.-D., S. J. Nesbitt, D. S. Berman and A. C. Henrici. 2011. A late-surviving basal theropod dinosaur from the latest Triassic of North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278:3459-3464.

#Effigia#Effigia okeeffeae#Poposaur#Pseudosuchian#Triassic#Archosaur#Reptile#Triassic Madness#Palaeoblr#Triassic March Madness#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

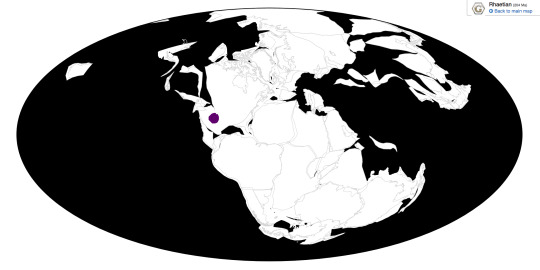

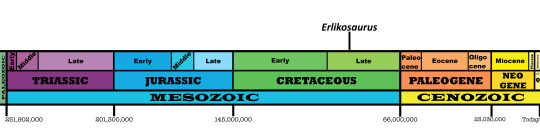

Erlikosaurus andrewsi

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Demon-King Reptile

First Described By: Perle, 1980

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Therizinosauria, THerizinosauridea, Therizinosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 90 million years ago, in the Turonian of the Late Cretaceous

Erlikosaurus is found in the Bayan Shireh Formation in Dornogovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Erlikosaurus was a kind of Therizinosaur, the very bulky feathered dinosaurs with long, pointed claws extending from their hands. They’re weird in other ways, too - they have backward-facing hip bones like those of birds and Ornithischians, and giant pot-bellies to let them digest large amounts of plant material. As such, they stood up almost as vertical as people do - rather than horizontally like… all other dinosaurs. Erlikosaurus had a long neck, a squat body, short legs and a short tail; while its arms were normal length, it also had very long curved claws, like other therizinosaurs. It had very large and long nostrils for a therizinosaur, and a very high number of teeth compared to its relatives. Interestingly enough, therizinosaurs like Erlikosaurus also had swollen, pneumatized braincases, which allowed them to be lighter weight and potentially cool off quicker. Erlikosaurus also, unlike other Therizinosaurs, ahd long and slender claws on its feet. It may have been around six meters long. Like other therizinosaurs, it would have been covered with feathers all over its body, and potentially had very primitive long feathers on its arms like wings.

Diet: Erlikosaurus, like other therizinosaurs, was an herbivore.

By Jack Wood

Behavior: Erlikosaurus is a fascinating dinosaur behavior-wise because we actually have a decent number of scans of its brain, which may teach us aspects of its behavior. Erlikosaurus had a very well developed sense of smell, hearing, and balanced, which means that it retained a lot of the traits of carnivorous theropods - and probably used them to its advantage as an herbivore. It also probably was able to sense oncoming predators well and have complex social behavior. The range of its mouth, however, was narrower than that of its close carnivorous relatives - indicating that herbivorous dinosaurs, much like herbivorous mammals, had smaller mouth gapes than carnivores. With complicated social behavior, long claws, and good senses, Erlikosaurus would have been incredibly paranoid - and dangerous - ready to fend off anyone that would have threatened their family groups with those long scythe claws. As a social dinosaur, Erlikosaurus would have probably taken care of its young, and been warm blooded. The scythe claws, when not used in defense, would have been helpful in gathering plants down from the trees, much like with sloths today.

Ecosystem: The Bayan Shireh Environment was one of many such ecosystems found in the mid to late Cretaceous, showcasing a wide variety of animals that were almost - but not quite - like their latest Cretaceous counterparts. Here was a braided river environment, going through season wet and dry seasons as the mud and sand interchanged from one another leading to a variety of rock types and depositional environments. There were many water plants and flowering plants lining the shores, giving it a lush and green feel for at least part of the year - and giving Erlikosaurus something to eat! There were also fish, molluscs, the mammal Tsagandelta, and turtles making frequent appearances in the environment. Unnamed crocodylian relatives and Azhdarchid pterosaurs were present, but most of the charismatic animals present were other dinosaurs. Erlikosaurus wasn’t the only Therizinosaur, and also lived with Segnosaurus and Enigmosaurus. The very large, weird, and lopsided sauropod Erketu graced the treetops, slowly foraging on food, while the much smaller Ornithomimosaur Garudimimus scurried about between them all. Ankylosaurs went absolutely wild here, represented by Talarurus, Maleevus, and Tsagantegia. There were two small bipedal Ceratopsians, Graciliceratops and Microceratus, and the early hadrosauroid Gobihadros. There was also a mystery dinosaur, Amtosaurus, which has no affinity beyond “Ornithischian” at this point in time. As for predators, there was the very large raptor Achillobator and the small tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus - both similar in size to one another, and both giant dangers to the roaming herds of Erlikosaurus!

By Scott Reid

Other: Erlikosaurus was a very advanced therizinosaur, similar to later members of the group like Therizinosaurus rather than Early Cretaceous varieties. As such, it shows that the more classic therizinosaur body shape was around by the “mid” Cretaceous. In addition, it may or may not be the same animal as the other therizinosaurs found in its home - more research is needed to determine as such.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Averianov, A. O. 2007. Theropod dinosaurs from Late Cretaceous deposits in the northeastern Aral Sea region, Kazakhstan. Cretaceous Research 28:532-544

Barsbold, R., and A. Perle. 1980. Segnosauria, a new infraorder of carnivorous dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 25(2):187-195

Barsbold, R. 1981. Bezzubyye khishchnyye dinozavry Mongolii [Toothless carnivorous dinosaurs of Mongolia]. Sovmestnaia Sovetsko-Mongol’skaia Paleontologicheskaia Ekspeditsiia Trudy 15:28-39

Barsbold, R. 1983. Khishchnye dinosavry mela Mongoliy [Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition 19:1-117

Barsbold, R. 1997. Mongolian dinosaurs. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 447-450

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Clark, J. M., T. Maryanska, and R. Barsbold. 2004. Therizinosauroidea. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 151-164

Clark, J. M., M. A. Norell, L. M. Chiappe and A. Perle. 1995. The phylogenetic relationships of "segnosaurs" (Theropoda, Therizinosauridae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3, supl.):24A

Clark, J. M., A. Perle, and M. A. Norell. 1993. The skull of the segnosaurian dinosaur Erlikosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13(3, suppl.):30A-31A

Clark, J. M., A. Perle, and M. A. Norell. 1994. The skull of Erlicosaurus andrewsi, a Late Cretaceous "segnosaur" (Theropoda: Therizinosauridae) from Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3115:1-39

Currie, P. J. 1992. Saurischian dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous of Asia and North America. In N. J. Mateer, P.-j. Chen (eds.), Aspects of Nonmarine Cretaceous Geology. China Ocean Press, Beijing 237-249

Currie, P. J., and D. A. Eberth. 1993. Palaeontology, sedimentology and palaeoecology of the Iren Dabasu Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China. Cretaceous Research 14:127-144

Currie, P. J. 2000. Theropods from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. In M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, & E N. Kurichkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia 434-455

Danilov, I. G. 1999. A new linholmemydid genus (Testudines: Lindholmemydidae) from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. Russian Journal of Herpetology 6(1):63-71

Eberth, D. A., P. J. Currie, D. B. Brinkman, M. J. Ryan, D. R. Braman, J. D. Gardner, V. D. Lam, D. N. Spivak, and A. G. Neuman. 2001. Alberta's dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates: Judith River and Edmonton groups (Campanian-Maastrichtian). In C. L. Hill (ed), Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 61st Annual Meeting, Bozeman. Guidebook for the Field Trips: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Paleontology in the Western Plains and Rocky Mountains, Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper 3:49-75

"Erlikosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 142.

Gianechini, F. A., P. J. Makovicky, and S. Apesteguía. 2011. The teeth of the unenlagiine theropod Buitreraptor from the Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina, and the unusual dentition of the Gondwanan dromaeosaurids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56(2):279-290

Hendrickx, C., and O. Mateus. 2014. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the indentification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa 3759(1):1-74

Hicks, J.F., Brinkman, D.L., Nichols, D.J., and Watabe, M. (1999). "Paleomagnetic and palynological analyses of Albian to Santonian strata at Bayn Shireh, Burkhant, and Khuren Dukh, eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia." Cretaceous Research, 20(6): 829-850.

Jerzykiewicz, T. and Russell, D.A. (1991). "Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin." Cretaceous Research, 12(4): 345-377.

Kirkland, J. I., D. K. Smith, and D. G. Wolfe. 2005. Holotype braincase of Nothronychus mckinleyi Kirkland and Wolfe 2001 (Theropoda; Therizinosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian) of west-central New Mexico. In K. Carpenter (ed.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 87-96

Lautenschlager, Stephan; Rayfield, Emily J.; Altangerel Perle; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (2012). "The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e52289.

Lautenschlager, Stephan (November 4, 2015). "Estimating cranial musculoskeletal constraints in theropod dinosaurs". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (11): 150495.

Li, D., C. Peng, H. You, M. C. Lamanna, J. D. Harris, K. J. Lacovara, and J. Zhang. 2007. A large therizinosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of northwestern China. Acta Geologica Sinica 81(4):539-549

Mader, B. J., and R. L. Bradley. 1989. A redescription and revised diagnosis of the syntypes of the Mongolian tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus olseni. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9(1):41-55

Makovicky, P. J., and M. A. Norell. 1998. A partial ornithomimid braincase from Ukhaa Tolgod (Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia). American Museum Novitates 3247:1-16

Nessov, L. A. 1995. Dinozavri severnoi Yevrazii: Novye dannye o sostave kompleksov, ekologii i paleobiogeografii [Dinosaurs of northern Eurasia: new data about assemblages, ecology, and paleobiogeography]. Institute for Scientific Research on the Earth's Crust, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg 1-156

Paul, G. S. 1984. The segnosaurian dinosaurs: relics of the prosauropod-ornithischian transition?. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 4(4):507-515

Perle, A. 1977. O pervoy nakhodke Alektrozavra (Tyrannosauridae, Theropoda) iz pozdnego Mela Mongolii [On the first discovery of Alectrosaurus (Tyrannosauridae, Theropoda) in the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Shinzhlekh Ukhaany Akademi Geologiin Khureelen 3(3):104-113

Perle, A. 1981. Noviy segnozavrid iz verchnego mela Mongolii [A new segnosaurid from Mongolia]. Trudy - Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya 15:50-59

Pu, H., Y. Kobayashi, J. Lu, Y. Wu, H. Chang, J. Zhang, and S. Jia. 2013. An unusual basal therizinosaur with an ornithischian dental arrangement from northeastern China. PLoS ONE 8(5):e63423

Qian, M.-p., Z.-y. Zhang, Y. Jiang, Y.-g. Jiang, Y.-j. Zhang, R. Chen, and G.-f. Xing. 2012. [Cretaceous therizinosaurs in Zhejiang of eastern China]. Journal of Geology 36(4):337-348

Rauhut, O. W. M. 2003. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 69:1-213

Russell, D. A. 1997. Therizinosauria. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 729-730

Russell, D. A., and Z.-M. Dong. 1994. The affinities of a new theropod from the Alxa Desert, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 30(10-11):2107-2127

Senter, P., J. I. Kirkland, and D. D. DeBlieux. 2012. Martharaptor greenriverensis, a new theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah. PLoS ONE 7(8):e43911:1-12

Sereno, P. C. 1998. A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 210(1):41-83

Sues, H.-D. 1997. On Chirostenotes, a Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from western North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17(4):698-716

Sukhanov, V. B., and P. Narmandakh. 1975. Cherepakhi gruppy Basilemys (Chelonia, Dermatemydidae) v Asiy [New turtles from the Basilemys group (Chelonia, Dermatemydidae) in Asia]. In N. Kramarenko, B. Luwsandansan, Yu. Voronin, R. Barsbold, A. Rozhdestvensky (eds.), Iskopaemaya Fauna I Flora Mongolii [Fossil Flora and Fauna of Mongolia]. Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya, Trudy [The Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition, Transactions] 2:94-101

Tsuihiji, T., M. Watabe, R. Barsbold and K. Tsogtbaatar. 2015. A gigantic caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 56(1):60-65

Turner, A. H., S. H. Hwang, and M. A. Norell. 2007. A small derived theropod from Öösh, Early Cretaceous, Baykhangor Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3557:1-27

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Xu, X., Z.-H. Zhang, P. C. Sereno, X.-J. Zhao, X.-W. Kuang, J. Han, and L. Tan. 2002. A new therizinosauroid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 40(3):228-240

Varricchio, D. J. 1997. Troodontidae. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 749-754

Zanno, L. 2004. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of a primitive therizinosauroid (Theropoda: Maniraptora): new information on the phylogenetics and evolution of therizinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(3, suppl.):134A

Zanno, L. E. 2006. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the primitive therizinosauroid Falcarius utahensis (Theropoda, Maniraptora): analyzing evolutionary trends within Therizinosauroidea. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(3):636-650

Zanno, Lindsay E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503–543.

Zhang, X.-H., X. Xu, X.-J. Zhao, P. C. Sereno, X.-W. Kuang and L. Tan. 2001. A long-necked therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol, People's Republic of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 39(4):282-290

#erlikosaurus#erlikosaurus andrewsi#dinosaur#therizinosaur#feathered dinosaurs#factfile#palaeoblr#feathered dinosaur#maniraptoran#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Herbivore#Theropod Thursday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

324 notes

·

View notes

Note

Has the Dinosaur Park therizinosaur been described?

Specimens of it have been briefly described and illustrated in Sues (1978) (though it hadn’t been identified as a therizinosaur then) and Currie (1992) in the book Aspects of Nonmarine Cretaceous Geology (which isn’t readily available online, as far as I can tell). It would be nice to see a more detailed reassessment of the material however, given that we know more about therizinosaur anatomy nowadays. The Theropod Database has more details, as usual (search for CMN 12349).

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Nonmariners #nonmariners2018 #cupmatchweekend #calicojacks #calicojacks2018 #bermynet #rdp #robertdanielsphotography #raftup #raftup2018 (at Somerset, Sandys, Bermuda)

#nonmariners#nonmariners2018#cupmatchweekend#calicojacks#calicojacks2018#bermynet#rdp#robertdanielsphotography#raftup#raftup2018

0 notes

Photo

Saying ✌🏽 to Bermuda and headed to Chicago for a few days. Excited to finally be going on vacation. I plan on eating a lot, relaxing, and being MIA. 😌👌🏽❤️ | #tamaraxo #latepost #nonmariners #gotobermuda (eventhoughimleavingrightnow) #bermudablogger #holidayswithtamara (at Bermuda)

0 notes

Text

fun fact: This is because the law originally covered "birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and fish", with marine invertebrates included in "fish", and at some point in the, like, 80s? When they wanted to cover nonmarine invertebrates, instead of adding "and invertebrates" they went "fuck it, snails are fish". The judges, looking at the ruling of "snails are fish", went "well fuck it, if snails are fish, bees are fish too".

Second fun fact: the best taxonomical classification for "fish" is "vertebrate that isn't a tetrapod (bird/mammal/amphibian/reptile)", so fish cannot be invertebrates. The moment they included something invertebrate (idk, crabs? jellyfish? anemones?) in the definition of fish, their fate was sealed.

great news

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

ANIMAL POPULATION OF THE SEA

The animals of sea (fauna) is very large, where the number of species is also large. The important groups of marine animals- (a) Invertebrates, (b) Vertebrates Invertebrates are animals lacking backbone, vertebrates are animals having a spinal column (backbone) and endoskeleton. Phylum: one of the large divisions in the classification of plants. (a) Invertebrates 1. Phylum Protozoa: Protozoa are single-celled organisms, microscopic. The pelagic forms inhabiting the plankton. 2. Phylum porifera: The sponges are multi cellular animals with spicules of silica or CaCO3 with fibrous skeletons made of the horny substance spongin. Sponges are benthic and marine. There are about 2500 species, mostly marine

3. Phylum coelenterata: These are primitive forms and show a remarkable degree of polymorphism i.e., a single species present a variety of forms. 4. Phylum ctenophora: Ctenophora are small globular jelly forms. The abundant community is called comb jellies or sea walnuts. There are 80 species, all marine. 5. Phylum Platyhelminthes: They are flat worms found in the sea. It has class turbellaria and class Nemertinea. The planktonic forms are modified and found in about 550 species of nemerteans, all are marine. 6. Phylum nemathelminthes: The roundworms occur largely as parasites, but some found in the plankton. There are about 1500 species, many of which are nonmarine. 7. Phylum trochelminthes: Class rotatoria. These are tiny benthic or planktonic organisms having rings of cilia for swimming and for gathering food. They are about 1200 species of rotifers, most are freshwater habitats. 8. Phylum bryozoa: These are colonial animals known as “Sea mats” or ‘moss animals’. They are more than 3000 species, about 35 of which are non-marine. 9. Phylum brachiopoda: These are ancient sessile animals, resembling bivalve molluscs. They grow permanently attached to rocks and shells in the littoral zone below low tide. About 120 living and 3500 fossil species are known. 10. Phylum phoronidea: Phoronidea are wormlike animals. These are about 12 marine species. 11. Phylum chaetognatha: These are numerous

0 notes

Text

Bumbershoot Policy

Bumbershoot is a specialized form of liability insurance that covers nonmarine and maritime liability exposures. http://vastseek.com/sources/12-investopedia/43414-bumbershoot-policy

0 notes

Text

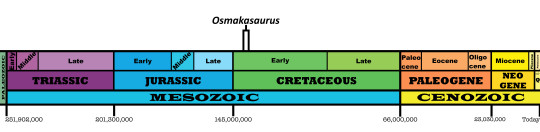

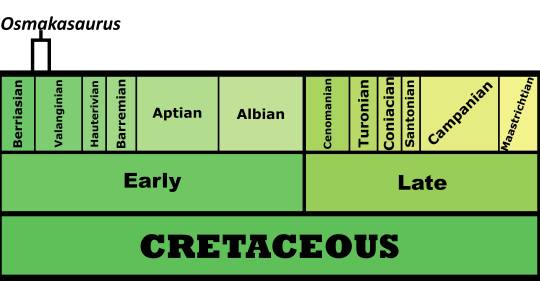

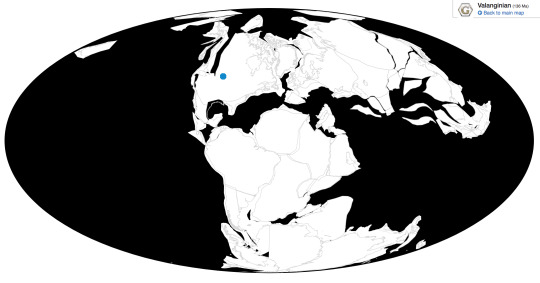

Osmakasaurus depressus

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Reptile from the Canyon

First Described By: McDonald, 2011

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 140 and 137 million years ago, from the Berriasian to the Valanginian ages of the Early Cretaceous

Osmakasaurus is known from the Chilson member of the Lakota Formation in South Dakota

Physical Description: Osmakasaurus was an animal fairly like Camptosaurus, a bulky bipedal herbivore with short arms and thick legs. It probably ranged between 4 and 5 meters long, and compared to its close relatives it had a fairly narrow and weirdly-shaped hip, though of course very little else is known of it to determine how else it may have differed from its close relatives. Osmakasaurus would have been primarily scaly, though it may have had some residual tufts of feathers or a feather cape of some sort for display.

Diet: Osmakasaurus would have been a mid-level browser, feeding on bushes and low-lying tree branches, probably specializing on tough vegetation like its close relatives.

Behavior: Osmakasaurus probably wasn’t a herding sort of animal - dinosaurs in this group of Ornithopods tend to be more solitary than the earlier flocks of small bipedal friends and the later magnificent herds of the later hadrosaurs. Instead, Osmakasaurus would have been fairly solitary, moving around its environment and trying to stick to places of denser vegetation in order to stay hidden. It is possible that it formed family groups during the mating season - it almost decidedly took care of its young, so it is not unreasonable to suppose that mated pairs would care for the young during the season together, but that would probably be the extent of its social behavior after leaving the families. They would have been somewhat slow animals, given their size, but able to run when needed.

Ecosystem: The Chilson environment was a sandy floodplain, filled with winding rivers and greatly affected by seasonal ebbs and flows of water. As such it was mainly filled with plants able to deal with these changes - hardy conifers and seed ferns, though there were some leptosporangiate ferns as well. These rivers, though fickle, hosted a wide variety of animals in addition to Osmakasaurus. There were many types of fish, as well as mammals such as Bolodon, Passumys, Lakotalestes, and Infernolestes. Other dinosaurs mainly included other herbivores - an ankylosaur, Hoplitosaurus; some sort of large sauropod; and a more Iguanodon-like Ornithopod, Dakotodon.

Other: Osmakasaurus used to be a species of Camptosaurus, since the latter was a wastebasket taxon in which large, bipedal ornithopods that weren’t quite Iguanodon-like enough were dumped into. It was since separated out, but not much more has been said about it. It was close to being Iguanodon, but not quite, and so still was in the group of generic-Camptosaurus-esque things. It is only known from scattered remains.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Cifelli, R.L., Davis, B.M., and Sames, B. 2014. Earliest Cretaceous mammals from the western United States. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 59 (1): 31–52.

D'Emic, M. D., & J.R. Foster (2014) The oldest Cretaceous North American sauropod dinosaur. Historical Biology (advance online publication) DOI:10.1080/08912963.2014.976817

Gilmore, C.W., 1909. Osteology of the Jurassic reptile Camptosaurus, with a revision of the species of the genus, and description of two new species. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 36: 197-332.

McDonald, A.T., 2011. The taxonomy of species assigned to Camptosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda). Zootaxa 2783: 52-68.

Ruiz-Omeñaca, L. Piñuela, J. C. García-Ramos. 2012. New ornithopod remains from the Upper Jurassic of Asturias (North Spain). 10th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists. ¡Fundamental! 20: 219 - 222.

Sames, B., Cifelli, R.L., and Schudack, M. 2010. The nonmarine Lower Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior foreland basin: new biostratigraphic results from ostracod correlations, and their implications for paleontology and geology of the basin—an overview. Earth-Science Reviews 101: 207–224.

#Osmakasaurus#Osmakasaurus depressus#Dinosaur#Ornithopod#Ankylopollexian#Palaeoblr#Cretaceous#North America#Herbivore#Mesozoic Monday#Dinosaurs#Prehistoric Life#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

122 notes

·

View notes

Video

Chinle Formation badlands (Upper Triassic; Painted Desert, Arizona, USA) 16 by James St. John

Caption enclosed;

Mudshales in the Triassic of Arizona, USA.

The Chinle Formation is a widespread, nonmarine, siliciclastics-dominated unit, principally representing deposition in ancient fluvial and lacustrine environments. The Chinle outcrops in southwestern America, principally in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, but also including portions of Colorado and Nevada.

In the Painted Desert region of Arizona, colorful mudshales of the Chinle Formation have weathered and eroded into a spectacularly scenic landscape. In the above photo, reddish shales of the Petrified Forest Member are present. This stratigraphic member also includes some sandstone beds, and evaporitic gypsum is present in places. The shales are floodplain deposits. The sandstones are river channel deposits.

The Chinle Formation is generally not resistant to weathering and frequently forms distinctive badlands. "Badlands" refers to a landscape unsuitable for farming. Such terrains are complexly dissected (eroded), have steep slopes, relatively soft rocks (usually shale), little to no soil, and little to no vegetation. Good examples of badlands topography are the Mancos Shale badlands of Utah-Colorado, the White River badlands of South Dakota (Badlands National Park), and the Little Missouri badlands of North Dakota (Roosevelt National Park).

Stratigraphy: Petrified Forest Member, upper Chinle Formation, Norian Stage, Upper Triassic, ~213 Ma

Locality: Painted Desert (view from Tawa Point along Petrified Forest Road), northern Petrified Forest National Park, near the western border of Apache County, eastern Arizona, USA

0 notes

Text

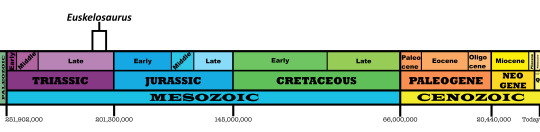

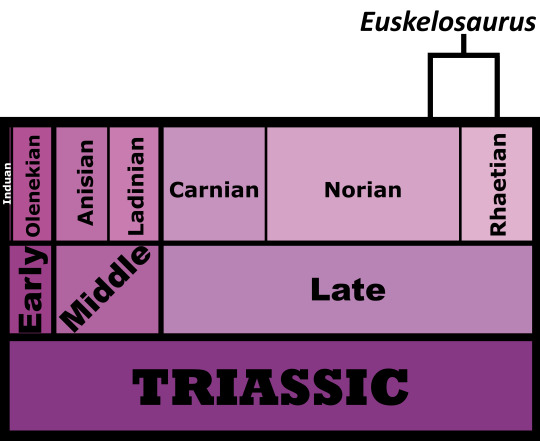

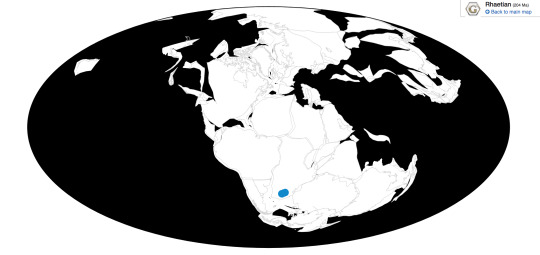

Euskelosaurus browni

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Good Leg Reptile

First Described By: Huxley, 1866

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Bagualosauria, Plateosauria, Plateosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Around 210 to 205 million years ago, from the Norian to the Rhaetian ages of the Late Triassic

Euskelosaurus is known from the lower Elliot Formation of South Africa

Physical Description: Euskelosaurus would have been a somewhat large, robust early sauropodomorph, possibly ten meters in length. It probably would have had long arms with long claws on the fingers, but they wouldn’t have had long enough arms to reach the ground. Euskelosaurus would have also had robust legs and a long tail. Its neck would have been long, ending in a small head. It might have been covered in some sort of fluffy covering, though we can’t be sure. It probably would have been quite heavy in general.

Diet: Euskelosaurus would have probably been an herbivore, most likely a mid-level browser.

Behavior: It is difficult to say exactly what the behavior of Euskelosaurus would have been, given it’s known from kind of poor remains. However, we can guess some things. Based on relatives like Massospondylus and the dinosaur family tree in general, it probably took care of its young. Based on other prosauropods, it probably lived in herding groups. And, given its size, it probably spent most of its time eating plant food. It also would have been active and warm-blooded, but not very fast. It’s claws could have been used to strip leaves off of branches, and its small head would have been able to weave in between dense foliage.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Euskelosaurus lived in the Elliot Formation, a famous fossil ecosystem of Triassic to Early jurassic age animals showcasing how life evolved around the Triassic-Jurassic extinction and how dinosaurs began to explode into new forms right after the extinction. Unfortunately, Euskelosaurus hails from the early part of that ecosystem - the more poorly known Triassic member, where dinosaurs are few and far between, as are other animals. This makes Euskelosaurus important, being one of few dinosaurs known from this ecosystem, but also explains its poor condition. This was a semi-arid floodplain and lake system, with very long dry seasons and flash-in-the-pan wet seasons. It was primarily filled with conifers, as well as some horsetails and cycads.

It’s difficult to say exactly what animals Euskelosaurus lived with, given that the organization of the formation is murky and there are animals that are actually in the Upper Elliot Formation that were originally said to be in the Lower. However, Euskelosaurus probably lived alongside other Sauropodomorphs, including Eucnemesaurus, Plateosauravus, Blikanasaurus, and maybe others. There would have also been cynodonts, weird crocodile relatives, and even predatory dinosaurs. Until more is sorted out, however, it’s difficult to say.

Other: Euskelosaurus was a prosauropod, a type of dinosaur from which the larger sauropods would evolve at the end of the Triassic. It seems to be closely related to the better known Plateosaurus.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bordy, E.M.; Eriksson, P. (2015-09-01). "LITHOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE ELLIOT FORMATION (KAROO SUPERGROUP), SOUTH AFRICA". South African Journal of Geology. 118 (3): 311–316.

Broom, R. (1911). "On the dinosaurs of the Stormberg, South Africa". Annals of the South African Museum. 7: 291–308.

Cooper, M.R. (1980). "The first record of the prosauropod dinosaur Euskelosaurus from Zimbabwe". Arnoldia Zimbabwe. 9 (3): 1–17.

Durand, J.F. (2001). "The oldest juvenile dinosaurs from Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 33 (3–4): 597–603.

Galton, Peter M. (1985). "Notes on the Melanorosauridae, a family of large Prosauropod Dinosaurs (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha)". Geobios. 18 (5): 671–676.

Gauffre, Francois-Xavier (1993). "Biochronostratigraphy of the Lower Elliot Formation, southern Africa) and preliminary results on the Maphutseng dinosaur. Saurischia: Prosauropoda) from the same Formation of Lesotho". In Lucas, Spencer G.; Morales, Michael (eds.). The Nonmarine Triassic: Bulletin 3. pp. 147–9.

Huxley, TH (1866). "On the remains of large dinosaurian reptiles from the Stormberg mountains, South Africa". Geological Magazine. 3: 563–4.

McPhee, Blair Wayne (2016). The South African Mesozoic: advances in our understanding of the evolution, palaeobiogeography, and palaeoecology of sauropodomorph dinosaurs (Thesis).

McPhee, Blair W.; Choiniere, Jonah N. (2016). "A hyper-robust sauropodomorph dinosaur ilium from the Upper Triassic–Lower Jurassic Elliot Formation of South Africa: Implications for the functional diversity of basal Sauropodomorpha". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 123: 177–184.

McPhee, B. W., E. M. Bordy, L. Sciscio, J. N. Choiniere. 2017. The sauropodomorph biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of Southern Africa: Tracking the evolution of Sauropodomorpha across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (3): 441 - 465.

Sciscio, Lara; De Kock, Michiel; Bordy, Emese; Knoll, Fabien (2017-11-01). "Magnetostratigraphy across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary in the main Karoo Basin". Gondwana Research. 51: 177–192.

Seeley, H.G. (1894). "XLI.—On Euskelesaurus Brownii (Huxley)". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 14 (83): 317–340.

Tankard, Anthony; Welsink, Herman; Aukes, Peter; Newton, Robert; Stettler, Edgar (2009-09-01). "Tectonic evolution of the Cape and Karoo basins of South Africa". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (8): 1379–1412.

Van Heerden, J. (1979). The morphology and taxonomy of Euskelosaurus (Reptilia: Saurischia: Late Triassic) from South Africa. Nasionale Museum.

Welman, Johann (1999). "The basicranium of a basal prosauropod from the Euskelosaurus range zone and thoughts on the origin of dinosaurs". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 29 (1): 227–232.

Yates, A.M. (2004). The death of a dinosaur: dismembering Euskelosaurus. Geoscience Africa. p. 715.

#Euskelosaurus#Euskelosaurus browni#Prosauropod#Dinosaur#Sauropodomorph#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Triassic#Africa#Herbivore#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

184 notes

·

View notes