#nohopereadio

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I went to the Wikipedia page on Les Champs magnétiques (a French surrealist novel written entirely as automatic writing, i.e. typing whatever words come into your head without trying to make them mean anything), which is one of the Wikipedia pages I remember being fascinated by as a young teen first discovering Wikipedia, when at least a couple of you were literally not even born yet, or like barely born. The very short article hasn't changed much since 20 years ago except that the example passage they quote is now a different one for some reason, which I noticed immediately on account of the vibes being wrong despite the new passage also mentioning train stations, and I had to go back to an older revision to see the one I remember from my youth:

The marvellous railway-stations never afford us shelter anymore: the long passages terrify us. So in order to go on living these monotonous minutes must still be stifled, these scraps of centuries. Once we loved the year's last sunny days, the narrow plains where our eyes' gaze flowed like those impetuous rives of our childhood. There remain nothing but reflections now in the woods repopulated with absurd animals, with well-known plants.

For some reason I felt like going back even further to the very first version of the article, created May 8th 2004, and I was rewarded with the fact that the user who initially created the article for Les Champs magnétiques (and the current version is still mostly their work actually) decided to get a bit self-referential and wacky with it; this is how their original version ends:

Keeping the spirit of surrealism, the rest of this entry is done using automated writing (spelling mistakes and all): A strange french book, is this book. I can try to read it but sometinmes I have trouble, especisallym wsince my essay is due in Monday. I have boorrowed a lot of books from the library. Perhapos I can do an automated essay? I mentioned it to my lecturerer and he said it would not work. I wonder if the wiklipedia people will accept this entry. I think they are too strict and it is a pity that surrealism is not an accepted technique if these people knew anything about post-modernism they would realise that everythign like this is valid on some level althought I guess I haven't really spoken about the book, yeah its good, there is poetry towards the end so it's not really a novel.

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is from Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett:

---

This is being written with green ink—though in fact it is not, not yet. Quite some time has passed since this pen was last used—and, compared to the other fountain pen I have, which is used very often, it is indeed rather unwieldy—and perhaps for that reason alone I am finding it quite difficult to just get on with something.

It would seem the last time it was used the ink running from its nib was blue black. In fact it still contained the old cartridge, more or less empty, and I wonder—I can’t help it— where all the ink from that cartridge went. Quite some time has passed you see since this pen was last used and actually I have a fair idea where most of the ink from that last cartridge went because the pen itself had been a gift as a matter of fact, and since there was a notebook along with it too it’s reasonable to suppose that the two things combined, just in the way the person who made the gift had intended.

How very diligent of me.

Even now, this far in, the words here are still coming blue black—and give no indication of changing. Not so much as a hint, which I think is unusual. How can that be? I don’t see anything odd or ridiculous about writing in green by the way; but, alas, it is not really something you can go on with once you’ve come across those unkind and boorish remarks and recognised the stigma attached, and then of course one just feels very embarrassed as if caught out and doesn’t do it any more and sort of pretends they never did. The reason why it’s happening again now, or soon will be, is not because I have recently returned to green ink but because recently a cartridge of green ink was discovered in the bottom of a shopping bag I haven’t used for a very long time. The reason I haven’t used this particular shopping bag for a long time is because it has wheels, and while it was very useful to have a shopping bag with wheels when I lived in the city, it is completely impractical now that I no longer live in the city, and so the last time I used it was when I moved from the city and I filled it up with things from the kitchen cupboards in the house in the city I was moving from, and even then I didn’t put it to its proper use and pull it along on its wheels from the house, a man carried it over his shoulder from the kitchen to a van that was quickly filling up with my stuff from the house I was moving away from in the city. Sure enough the shopping bag with wheels was stuffed with bubble wrap, which I’m sure I will need again one day, but I’m sure I don’t need to hang onto this particular bundle, so I discarded the bubble wrap actually, and then, at the bottom of the bag, well not very much really. A battery of course always a battery, a very small whisk, and a Sheaffer cartridge of green ink.

what are some short examples of what you would consider to be "good prose"? I'm curious to learn more about your guys's tastes

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

famous authors we have nude photos of: Allen Ginsberg, Simone de Beauvoir, Patricia Highsmith, Eve Babitz...... there must be others

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The chapter from Dorian Gray that just lists all the many and various sensual pleasures Dorian indulges in in his new life of dandyism is one of the most boring chapters in anything ever. I haven't read it lately I just thought of it randomly. It's boring enough that part of me suspects it's boring on purpose to make a point. But that would be dumb I prefer to think it's boring on accident.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

did i already ask you which book you think is best to start with iris murdoch? i keep wanting to read her but havent gotten pulled in

I would rec A Fairly Honourable Defeat for starting out! It's top tier and it has very high concentrations of all the Murdoch hallmarks, the weird sexual energy, characters abruptly breaking into intense philosophical debates, the intricate but wild and almost soap opera-esque plotting. The comedic stuff is more foregrounded, not that it's "a comedy" at all. The gayness is less subdued than in many other of her books, if that's a draw for you? Julius King is one of her very best characters (can only think of one plausible competitor). If that one doesn't hold your interest you're probably safe to give up on her, it's pretty exemplary of what the Murdoch thing is, I would say.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

@the-lilac-grove:

I always struggle with Persuasion, in part because it's the only Austen novel that was published that she didn't get to finish / polish. She wrote a first draft, died, and it was published. Every other novel, she went back and revised over and over, refining and improving it. Persuasion is the one time we get to read a first draft from Austen. Which is, in its way, fascinating. But I wish we could have seen what the novel would have been if she'd had the same chance to revise and polish it the way she did with everything else. It feels like a great start of an idea that never got a chance to fully realize its potential.

Oh I knew it was posthumous but I didn't know the part about it getting less dev time than the other novels... I finished it since writing the OP and the second half is definitely stronger but it feels like clearly a minor work compared with P&P and Emma, despite me being in the lonely 30ish-year-old target audience who are supposed to like this one!

One thing I'll bring up, not because it super bothered me but because it feels representative of the book feeling relatively thin: what's the deal with the Benwick/Louisa engagement? Like Benwick is introduced as one of the more likeable and intelligent characters, the engagement is announced off-screen and everyone thinks it makes no sense and Anne is like "wow, I guess people just do crazy shit sometimes"--and I feel like in any other Austen novel this would be setting us up to gradually uncover some hidden motivations or something that make it all make sense. But in fact it seems like the explanation really is just that people do crazy shit sometimes? I don't know it's kind of weird I think! I feels very un-Austen to let something like that resolve with such a lack of complication.

(To be clear I enjoyed the book a lot, it's still 300 pages of Jane Austen prose, there's a high floor on that, my disappointment is relative to the other books!)

I'm about 100 pages into Persuasion and it's kind of a weird reading experience. I think in a bad way? I mean Jane Austen can't really not be entertaining so I'm still enjoying it but, so far Anne seems like the most weakly written of the Austen protagonists. One of her major traits is that no one wants to talk to her, which is fine but it means she gets less dialogue than basically every other character including pretty minor ones; I really don't have a sense of this girl's voice at all, and Austen characters are really a lot about the voice usually so it's a very noticeable lack! But then her inner life doesn't seem that rich either, her thoughts seem to entirely consist of 1) anxiety and embarrassment around Wentworth, and since that's the main plot it's kind of obligatory, and 2) internally rolling her eyes at her silly relatives making fools of themselves, which isn't exactly endearing but more to the point it's not all that revealing of her character, it feels like she exists largely to be a straight man to the others. Like she's clearly the protagonist but the book doesn't seem to give much of a shit about her...?

Especially coming to this quite soon after reading Emma the contrast in this regard is super jarring...

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did track down the paragraph I was talking about in this post by the way, with more difficulty than I expected. It's from Rilke's The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. It's actually quite different from my memory. It's also pretty long, I've had to split it into two paragraphs to get around tumblr's character-per-block limit!! So this was all one long paragraph in the original:

Will anyone believe that there are such houses? No. They will say that I’m falsifying. But this time it’s the truth, nothing left out and naturally also nothing added. Where should I get it from? It’s well known that I’m poor. Everyone knows. Houses? But, to be precise, they were houses that no longer existed. Houses that were torn down from top to bottom. What was there was the other houses, the ones that had stood alongside them, tall neighboring houses. They were obviously in danger of collapsing after everything next to them had been removed, for a whole framework of long tarred poles was rammed aslant between the ground of the rubble-strewn lot and the exposed wall. I don’t know whether I’ve already said that I mean this wall. But it was, so to speak, not the first wall of the present houses (which nevertheless had to be assumed) but the last one of the earlier ones. You could see their inner side. You could see the walls of rooms on the different storeys, to which the wallpaper was still attached, and here and there the place where the floor or ceiling began. Along the whole wall, next to the walls of the rooms, there still remained a dirtywhite area, and the open rust-stained furrow of the toilet pipe crept through it in unspeakably nauseating movements, soft, like those of a digesting worm. Of the paths taken by the illuminating gas, gray dusty traces were left at the edges of the ceilings, and here and there, quite unexpectedly, they bent round about and came running into the colored wall and into a black hole that had been ruthlessly ripped out.

But most unforgettable were the walls themselves. The tenacious life of these rooms refused to let itself be trampled down. It was still there; it clung to the nails that had remained; it stood on the handsbreadth remnant of the floor; it had crept together there among the onsets of the corners where there was still a tiny bit of interior space. You could see that it was in the paint, which it had changed slowly year by year: from blue to an unpleasant green, from green to gray and from yellow to an old decayed white that was now rotting away. But it was also in the fresher places that had been preserved behind mirrors, pictures and cupboards; for it had drawn and redrawn their contours and had also been in these hidden places, with the spiders and the dust, which now lay bare. It was in every streak that had been trashed off; it was in the moist blisters at the lower edge of the wall-hangings; it tossed in the tom-off tatters and it sweated out of all the ugly stains that had been made so long ago. And from these walls, once blue, green, and yellow, which were framed by the tracks of the fractures of the intervening walls that had been destroyed, the breath of this life stood out, the tough, sluggish, musty breath which no wind had yet dispersed. There stood the noondays and the illnesses, and the expirings and the smoke of years and the sweat that breaks out under the armpits and makes the clothes heavy, and the stale breath of the mouths and the fusel-oil smell of fermenting feet. There stood the pungency of urine and the burning of soot and the gray reek of potatoes and the strong oily stench of decaying grease. The sweet lingering aroma of neglected suckling infants was there and the anguished odor of children going to school and the sultriness from beds of pubescent boys. And much had joined this company, coming from below, evaporating upward from the abyss of the streets, and much else had seeped down with the rain, unclean above the towns. And the domestic winds, weak and grown tame, which stay always in the same street, had brought much along with them, and there was much more too coming from no one knows where. But I’ve said, haven’t I, that all the walls had been broken off, up to this last one? Well, I’ve been talking all along about this wall. You’ll say that I stood in front of it for a long time; but I’ll take an oath that I began to run as soon as I recognized the wall. For that’s what’s terrible—that I recognized it. I recognize all of it here, and that’s why it goes right into me: it’s at home in me.

My memory has altered this beyond recognition in the 12 years or so since reading it: I remember the narrator recognizing a house while walking out in open country, which is completely different; I remember something about a wall being in a state of shabby disrepair but I don't remember the whole building being partially demolished so that only one wall is left. Most of this paragraph is incompatible with what I had in mind, I think really the only thing I latched onto was the sentence near the end where after the lengthy description the narrator reveals that they only saw the house for a fraction of a second before running away, which I still think is a cool way of showing that weird compressed-time effect you get in certain high-adrenaline moments.

But apart from that I'm not sure I even did more than skim the whole passage at the time. Which isn't surprising I guess because it's actually very boring! Like even as I was braced for disappointment, this is quite disappointing. I'll probably still read the book at some point but I have to say I'm not eager.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I were writing a novel, I would certainly not have any long (a page or more) passages be in italics, and I especially would not do that as a recurring thing. Even if those parts are flashbacks or dreams or a mysterious different narrator or something, I would find some other way to convey that those passages are A Different Kind Of Deal. Stop having them be in italics I don't like that cut it out

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virginia Woolf makes for far better out-and-about reading than at-home reading imo. Always puts me in a people-watching mood, she might be the very best author for making plausible the illusion that everything everyone does is already maximally interesting and that art doesn't need to add anything. Maybe it's not an illusion if you have Virginia Woolf's brain. Or maybe it's the London that's the secret, maybe London's not bluffing about being the only real city, I mean how would I know? Maybe I gotta be in London. I'm not doing that though

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was March and the wind was blowing. But it was not “blowing.” It was scraping, scourging. It was so cruel. So unbecoming. Not merely did it bleach faces and raise red spots on noses; it tweaked up skirts; showed stout legs; made trousers reveal skeleton shins. There was no roundness, no fruit in it. Rather it was like the curve of a scythe which cuts, not corn, usefully; but destroys, revelling in sheer sterility. With one blast it blew out colour–even a Rembrandt in the National Gallery, even a solid ruby in a Bond Street window: one blast and they were gone. Had it any breeding place it was in the Isle of Dogs among tin cans lying beside a workhouse drab on the banks of a polluted city. It tossed up rotten leaves, gave them another span of degraded existence; scorned, derided them, yet had nothing to put in the place of the scorned, the derided. Down they fell. Uncreative, unproductive, yelling its joy in destruction, its power to peel off the bark, the bloom, and show the bare bone, it paled every window; drove old gentlemen further and further into the leather smelling recesses of clubs; and old ladies to sit eyeless, leather cheeked, joyless among the tassels and antimacassars of their bedrooms and kitchens. Triumphing in its wantonness it emptied the streets; swept flesh before it; and coming smack against a dust cart standing outside the Army and Navy Stores, scattered along the pavement a litter of old envelopes; twists of hair; papers already blood smeared, yellow smeared, smudged with print and sent them scudding to plaster legs, lamp posts, pillar boxes, and fold themselves frantically against area railings.

This is from Virginia Woolf's The Years. Imagine sitting down to write about a windy day in London and you just have this available to give, what does it feel like to have this paragraph among the possible acts of your mind

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A small number of classics publishing thoughts

I wish it were way more common to see long books published in multiple volumes. I'm fine with long books existing but a 900 page paperback is not good to hold in your hands. It's bad to hold. It's heavy for example. I don't wanna do that. If there were two of them but smaller it would be fine.

And I get why this doesn't happen in general, if you need to buy two books that's going to be more expensive, customers en masse wouldn't like it. But I'm puzzled about classics publishing specifically, because this is where choice, in theory, abounds. If I want a copy of War and Peace, I can cheap out on a £3.99 Wordsworth edition that probably uses a public domain translation and will definitely fall apart before I finish it, I can pay £9 more for the privilege of real paper and footnotes from Penguin/Oxford/Vintage/etc, I can pay £9 more than that for a tacky Penguin Clothbound edition because a straight person on instagram told me to, and above that there's varying degrees of actually nice expensive gift editions, I mean the Folio Society has proven that there's really no upper-bound to what people will pay for a book that looks really good.

What I can't seem to do, for any amount of money, is buy a paperback that is the size of my hands. I literally can't do it. All of the above are single volume and between 1000-1500 pages. The Everyman's Library War and Peace is in three volumes but hardback, and hardback is a significant disadvantage imo but that's probably genuinely the best option still. And that's a special exception anyway, Everyman's doesn't make a habit of doing this, their edition of Middlemarch for example is one 900-page volume, same with the other longboys I checked.

Surely there is room in this variegated competitive market for one edition that prioritizes comfort, for people who want to actually read the book and have a nice time doing so. It seems like there's not. Oh well.

---

I made fun of the Penguin Clothbound series above, and listen if you think they look cool and not like something conceived by a graphic design student who's just looked up what books are as research for their assignment then more power to you, but you still shouldn't buy them because they suck, like the quality is so bad! That coloured ink rubs off so easily it's insane. Part of my job involves picking books from the shop floor for online orders, and I hate seeing orders for the those ones because it's a very frequent occurrence that we'll have like six copies of the clothbound Frankenstein or whatever in-store and I still can't fulfill the order because none of them are remotely presentable, they've all got prominent scratches or faded parts, and this is before they've ever even been owned by anyone, this is just from existing in a shop and getting occasionally manhandled! It's so so sad. And the thing is a lot of books age gracefully, they look nice and well-loved as they get battered and worn, but these ones when the ink comes off just look like cheap pieces of shit! Please stop buying them, you do not want these books on your shelves trust me!

---

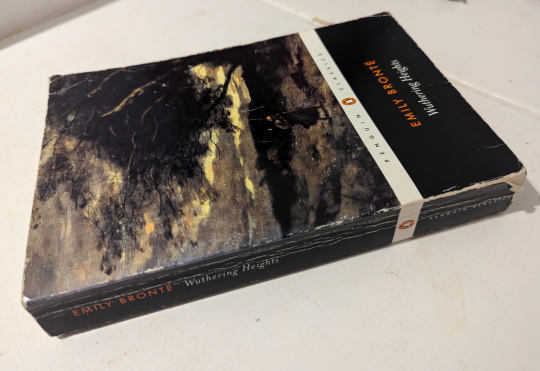

tbh the normal-ass Penguin Classic black paperbacks aren't always great quality either. My copy of Wuthering Heights looks like it's been passed down through three generations but I bought it new and I've only read it 1.5 times:

And like sure I let it get jostled around in my bag a lot but I do that with all my books and they don't all look like this. Definitely part of the issue is that it crinkles white which shows up really strongly against the black, but even allowing for that it's really bad. Penguin just kind of sucks with their classics publishing in general I think. It's weird because you'd think with no living author to pay royalties to there'd be more room for investing in an actual quality product--seems not! Most of my others in this series are kinda beat up too although admittedly this is the worst example.

(I don't even like Wuthering Heights it's kinda boring! The 0.5th read was my first attempt, I fell off it and then forced myself to try again later. I probably wouldn't still own it if it weren't sadly too ugly now to give away!)

---

Classics publishing! Just some thoughts.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

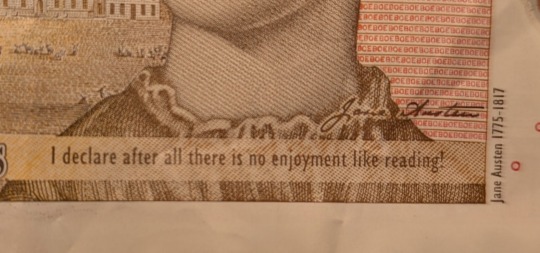

I'm assuming a bunch of you have heard of this before but while I'm Austenposting I'm gonna put it here because I still find it quite funny: the current Bank of England £10 note features a portrait of Jane Austen on one side with a quote from her underneath, "I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading!":

Which presumably came from someone on the design team googling "jane austen quotes" and picking one that sounded suitable and not digging deep enough to notice that this is actually a line of dialogue from Pride and Prejudice spoken by a character who finds reading boring but is pretending to like it to impress Mr Darcy:

Miss Bingley's attention was quite as much engaged in watching Mr. Darcy's progress through his book, as in reading her own; and she was perpetually either making some inquiry, or looking at his page. She could not win him, however, to any conversation; he merely answered her question, and read on. At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, "How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading!"

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first piece of fiction using [Jane Austen] as a character (what might now be called real person fiction) appeared in 1823 in a letter to the editor in The Lady's Magazine. It refers to Austen's genius and suggests that aspiring authors were envious of her powers.

Devastating that she didn't live long enough to see people writing rpf about how she's the best writer ever and all the other authors are jealous... (the story is here fwiw but paywalled so I can't get at it)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like many women authors at the time, Austen published her books anonymously. At the time, the ideal roles for a woman were as wife and mother, and writing for women was regarded at best as a secondary form of activity; a woman who wished to be a full-time writer was felt to be degrading her femininity, so books by women were usually published anonymously in order to maintain the conceit that the female writer was only publishing as a sort of part-time job, and was not seeking to become a "literary lioness" (i.e. a celebrity).

Okay this is just Wikipedia and the source isn't checkable-to-me but... huh! I knew about the thing where women writers would often publish either anonymously or with a male pseudonym, but I guess I assumed that was all for marketing reasons, the fear that people wouldn't be interested in buying books by women. Which is presumably still part of it. But I hadn't heard about this other angle where a woman using her own name might be shamed for, I guess, trying to make it part of her identity to be a writer? Like writing and publishing books is fine if you're not trying to make too big a deal about it, if you pretend to mostly care about other stuff? I mean that's not really worse than what I previously thought was the explanation, I guess, but it is fucked up in a novel and interesting way!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like Jane Austen a lot. I'm gonna attempt to say a few things about why:

It's very refreshing to read good fiction that takes seriously the importance of doing good by other people, and takes it seriously on lots of different scales: like there's big interpersonal conflict and moral dilemmas and stuff, but there's also like, spending an hour talking to your dad about cheerful things because you know he's likely to sit stewing in anxiety over something if you don't, even though you're kind of depressed at the moment and would rather be alone with your thoughts. That's a situation too!

Seriously it feels like not long after Austen fiction writers collectively agreed that all the interesting material was in the parts of the human mind that are normally hidden or repressed, or in people trying to forge some individual authentic path that's in conflict with the world or something, idk, maybe it's good that the thing I'm gesturing at happened. But I'm very glad we have at least one great novelist whose characters are primarily concerned with matters like "how can I best be a good friend to the people I care about?" and similarly-shaped questions.

I think part of this is just that like, there is no part of her that believes goodness is boring, she fundamentally takes for granted that people who are trying to be good are more interesting and complex and deep than people who aren't, and it's very hard not to agree with this when you're reading her.

Something about the very particular tone of her comedy is connected to all this, she's mocking, near-scathing about all her characters including the ones she likes, but it's from a place of like... the most important thing in life is to hold your principles sacred, but also it's a guarantee that you and the people around you will fall short of those principles many many times, but also the correct attitude to take towards these human limitations is laughter instead of despair, but also the most important thing in life is to hold your principles sacred. She really makes it feel like "people are ridiculous" and "people are important" are two sides of the same coin, idk this is more abstract than I want it to be, but something like that is the vibe.

It's frustratingly difficult to say anything general about her fiction that doesn't make it sound boring... anyway I love her is the point.

#nohopereadio#although I'm not really satisfied with this one it is still technically correct to tag it as#posts where I tried#uninteresting#jane austen

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

I liked this moment from my current book (which is Tirra Lirra by the River from 1978), on the subject of what gets left out of art. The context is, our narrator is in need of an abortion; it's 1930s London, where she's just migrated from Sydney, Australia; she's very recently reunited with her best friend from her teenage years, who is now a novelist, and who knows somebody who can help, but the friend is hesitant at first:

Olive chewed her lip again, and I waited again. Then she said with sudden resolution, ‘I’ll ask this woman, of course. It’s only that it’s so frightfully embarrassing. She’ll think it’s for me.’ I was amazed that she should care. Here was another problem of reconciliation. Her novels were so worldly, her ‘approved’ characters so far above the current moral laws. ‘Olive,’ I said, ‘what do your characters use?’ ‘Use?’ ‘What contraceptives? They have affairs, so they must use something, unless the men are sterile or the women barren. And they’re not, because they have children, or talk of having them. And what about Aldous Huxley’s characters? And Noel Coward’s? And D. H. Lawrence’s? Yes, his. What do they use?’ ‘You had better ask them,’ said Olive. ‘I can’t. But I can ask you. What do yours use?’ ‘I haven’t the faintest idea. Contraception—the avoidance of pregnancy—simply is not part of my theme.’ ‘What is your theme?’ ‘I suppose,’ said Olive, sounding shyer still, ‘the delicate nuances of feeling, you know, between a man and a woman in that position. I mean,’ she amended quickly, ‘in that relationship.’ ‘But wouldn’t those delicate nuances be affected by what they use? You can’t tell me it isn’t a nuance all of its own if a man has to stop to put something on, or a woman has to stop to put something in.’ But now Olive gave a laughing shriek and put both hands over her ears. And as I watched her laughing, and shaking her imprisoned head from side to side, I began to laugh myself. I could hardly believe that I should be shocking her (of all people!) in exactly the same way that the first lot of artists used to shock me at Bomera.

12 notes

·

View notes