#new railway lines Odisha

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Railway Line Doubling Survey Ordered for Tatanagar-Badampahar

New mineral transport centre planned in Badampahar, Odisha South Eastern Railway Zone initiates survey for Tatanagar-Badampahar rail line doubling, aiming to improve mineral transportation and passenger services. JAMSHEDPUR – The South Eastern Railway Zone has commissioned a survey and detailed project report for doubling the Tatanagar to Badampahar rail line, addressing growing transportation…

#बिजनेस#Badampahar mineral transport centre#business#Howrah-Mumbai route enhancement#Jamshedpur MP Bidyut Baran Mahto#mineral transportation improvement#new railway lines Odisha#Paradip port connectivity#Railway Infrastructure Development#regional economic growth#South Eastern Railway zone#Tatanagar-Badampahar rail doubling

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Indian Railways expands rail connectivity in western Odisha

Bhubaneswar/Bargarh: The Indian Railways has achieved significant progress in constructing the 138.32-km new railway line connecting Bargarh Road to Nawapara Road. This Special Railway Project is expected to revolutionise the transportation landscape in western Odisha by providing a new, shorter, and more efficient route for both passenger and freight services. The Bargarh Road–Nawapara Road…

0 notes

Text

CBI Team At Odisha Train Crash Site As Railways Hints At "Sabotage"

The CBI probe team arrived at the accident site in Balasore on Tuesday morning and will take over the investigation from Odisha police.

New Delhi: The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) will today take over the investigation into the horrific 3-train crash on Friday in Odisha’s Balasore that killed 278. The CBI probe team arrived at the accident site in Balasore on Tuesday morning and will take over the investigation from Odisha police.

The Odisha police have filed a case with charges of “causing death by negligence and endangering life” in the train accident.

The CBI stepping in is a significant move as officials say only a detailed probe by a top agency can establish criminal tampering, if any, with the point machine or the electronic interlocking system, or if the train changed tracks due to reconfiguration or a signaling error.

Railway officials had earlier indicated that possible “sabotage” and tampering with the interlocking system, which detects the presence of trains, led to the accident involving the Shalimar-Chennai Central Coromandel Express, the Bengaluru-Howrah Superfast Express, and a goods train.

The crash, involving two passenger trains and a goods train, killed 278 people and injured more than 800.

The railways said that according to the initial investigation, the accident was the result of a signalling problem and there was no collision.

Some railway experts have, however, questioned whether Coromandel Express may have hit the goods train directly inside a “loop line”.

A “loop line” divides from the main railway tracks and returns to the mainline after some distance, which helps manage busy rail traffic.

Visuals show the Coromandel Express’ engine resting on top of the goods train, indicating a straight collision.

The CBI inquiry will focus on answering all queries regarding the accident, the worst in the country in the last two decades. Government sources have said all angles will be investigated, including mechanical error, human error, and sabotage.

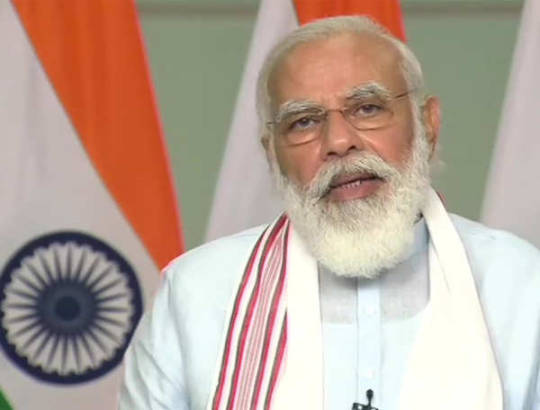

On Saturday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that strictest action will be taken against those found guilty.

0 notes

Text

Odisha Train Tragedy: Loco Pilots Didn't Exceed Speed Limit, Says Railways

NEW DELHI: The Railways absolved the loco drivers in the Odisha train tragedy of wrong-doing, saying that the Coromandel Express did not cross the speed limit and got the green signal to enter the loop line on which a goods train was waiting. The horrific train accident, involving the Shalimar-Chennai Central Coromandel Express, the Bengaluru-Howrah Superfast Express, and an iron- ore laden goods…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

BBC 0424 4 Jun 2023

12095Khz 0359 4 JUN 2023 - BBC (UNITED KINGDOM) in ENGLISH from TALATA VOLONONDRY. SINPO = 55445. English, dead carrier s/on @0357z then ID@0359z pips and newsroom preview. @0401z World News anchored by Neil Nunes. Initial investigations into the three train accidents in India revealed that the Coromandel Express train, which was involved in the tragic railway accident in the Indian state of Odisha, accidentally entered a loop side line and collided with a goods train that was stopped there, instead of taking the main line before the Bahanagar station. The carriages of the other “Bengaluru-Hora Superfast Express” train overturned after colliding with the coaches of the Coromandel Express, which were scattered on the adjacent track. China’s defence minister, Li Shangfu, has said a cold war mentality is resurgent in the Asia-Pacific region, but Beijing seeks dialogue over confrontation. The remarks came after Li refused to formally meet the US defence secretary, Lloyd Austin, at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. Twenty people have been injured - and it is feared that others are trapped - after an alleged Russian strike in Ukraine's central city of Dnipro. Explosions have also been heard over the capital, Kyiv, where air defence systems have again been deployed. All of Ukraine has been placed under air raid alerts. Russia has not commented on the latest events. Hong Kong police said on Sunday they had detained eight people near a park, four of them for "seditious intention and disorderly conduct", as authorities tightened security on the 34th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni said on Saturday that 54 Ugandan peacekeepers were killed in an attack last week by militant group al Shabaab on a military base in Somalia. Museveni said the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) had since recaptured the base from the Islamist group. The protests after the prison sentence against left-wing extremist Lina E. continued in Leipzig during the night. In the city there are “groups of apparently violent” people in various places, the Saxon police said on Twitter. Three Chinese astronauts are safely back on Earth after a smooth weekend landing to end a six-month mission to the country's Tiangong space station. @0406z "The Newsroom" begins. 250ft unterminated BoG antenna pointed E/W, Etón e1XM. 250kW, beamAz 315°, bearing 63°. Received at Plymouth, United States, 15359KM from transmitter at Talata Volonondry. Local time: 2259.

0 notes

Text

261 Dead, 900 Injured After Horrific Three-Train Crash In Odisha

Coromandel Express Accident: The train was going from Howrah to Chennai, rammed into the derailed coaches of the other train, which was going from Bengaluru to Kolkata

New Delhi: At least 261 people were killed and around 900 were injured in a horrific three-train collision in Odisha's Balasore, officials said Saturday, the country's deadliest rail accident in more than 20 years. Prime Minister Narendra Modi will visit the train accident site and meet with injured people at hospitals in Cuttack, his office tweeted.

The crash involved the Bengaluru-Howrah Superfast Express, the Shalimar-Chennai Central Coromandel Express, and a goods train.

The accident saw one train ram so hard into another that carriages were lifted high into the air, twisting and then smashing off the tracks. Another carriage had been tossed entirely onto its roof, crushing the passenger section.

"Everything was shaking and we could feel the coach toppling," Sanjay Mukhia, a daily wage worker travelling to Chennai on the Coromandel-Shalimar Express, told NDTV, showing his injuries.

According to another survivor, severed limbs were scattered over the ripped metal wreckage.

"I was sleeping when the train derailed. Some 10-15 people fell over me. When I came out of the coach, I saw limbs scattered all around, a leg here, a hand there...someone's face was disfigured," the survivor said.

"The rescue operation has been completed and now the focus is on restoration work," Railways Spokesperson Amitabh Sharma said.

Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said a high-level committee will be set up to investigate the train crash.

Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik has declared one-day state mourning in view of the horrific train crash.

Mr Vaishnaw has announced compensation of ₹ 10 lakh for the families of those who have died, ₹ 2 lakh for those seriously injured and ₹ 50,000 for those who sustained minor injuries in the accident.

PM Modi too expressed his distress over the accident, and announced a compensation of ₹ 2 lakh for the family of the dead and ₹ 50,000 for the injured from the PM's National Relief Fund (PMNRF).

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee tweeted she is monitoring the situation continually personally with the Chief Secretary and other senior officers.

48 trains have been cancelled, 39 diverted and 10 trains have been short terminated due to the accident, which happened on the Howrah-Chennai main line in the Kharagpur division of the South Eastern Railway.

0 notes

Text

238 Dead, 650 Injured In Horrific Three-Train Accident In Odisha

Coromandel Express Accident: The train was going from Howrah to Chennai, rammed into the derailed coaches of the other train, which was going from Bengaluru to Kolkata

New Delhi: At least 238 people were killed and 650 injured in a horrific three-train collision in Odisha, officials said Saturday, the country's deadliest rail accident in more than 20 years. Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said a high-level committee will be set up to investigate the train crash.

The crash involved the Bengaluru-Howrah Superfast Express, the Shalimar-Chennai Central Coromandel Express, and a goods train.

The rescue operations are on and all hospitals in the nearby districts have been put on alert. Three NDRF units, 4 Odisha Disaster Rapid Action Force units, over 15 fire rescue teams, 30 doctors, 200 police personnel and 60 ambulances have been mobilised to the site, Odisha Chief Secretary Pradeep told NDTV.

Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik has declared one-day state mourning in view of the horrific train crash.

The Railway Minister visited the accident site this morning to take stock of the situation. "Restoration work will take place immediately. Staff and equipment is ready for restoration work, but our first priority is rescue and medical aid to those injured. We will know details only after a detailed inquiry. An independent inquiry will be done," he said.

Mr Vaishnaw has also announced compensation of ₹ 10 lakh for those who have died, ₹ 2 lakh for those seriously injured and ₹ 50,000 for those who sustained minor injuries in the accident.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi too expressed his distress over the accident, and announced a compensation of ₹ 2 lakh for the family of the dead and ₹ 50,000 for the injured from the PM's National Relief Fund (PMNRF).

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee tweeted she is monitoring the situation continually personally with the Chief Secretary and other senior officers.

So far, 18 long-distance trains have been cancelled due to the accident, which happened on the Howrah-Chennai main line in the Kharagpur division of the South Eastern Railway.

0 notes

Text

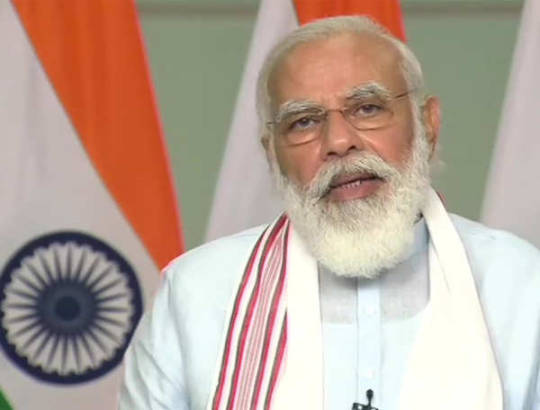

"PM Modi has set a target that Vande Bharat should reach almost all the states by June, confirms the Union Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnav

The 17th Vande Bharat Express was launched yesterday. The Union Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnav later said that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is very clear that these trains must reach almost all the Indian states by the next month.

Vaishnav spoke to ANI in Howrah, saying, "PM Modi has set a target that Vande Bharat should reach almost all the states by June...Vande Metro is being designed for a distance of less than 100 km and daily travel of passengers."

The first Vande Bharat train between Puri and Howrah was flagged off by PM Modi on Thursday. Vaishnav traveled on the Puri-Howrah Vande Bharat train and upon reaching Howrah, he said that the journey was very comfortable.

"The journey was extremely comfortable and the best part of the journey was interacting with youngsters and passengers," said the Union Minister.

The Prime Minister also laid the foundation stone via video conferencing and also promised several railway projects worth more than ₹8000 crores in Odisha. These projects cover flagging off the Vande Bharat Express to Howrah and setting the foundation stone for the renovation of Puri and Cuttack railway stations. 100% electrification of the rail network in Odisha along with a doubling of the Sambalpur-Titlagarh rail line and a new broad gauge rail line between Angul – Sukinda is also part of these projects.

In his address, the PM said that the launch of Vande Bharat in Odisha and West Bengal shows the way India is modernizing.

"India's speed and progress can be seen whenever a Vande Bharat Train runs from one place to another," the PM said.

For more national news India in Hindi, subscribe to our newsletter.

#Vande Bharat#national news India#vande bharat express#vande bharat train#werindia#leading india news source#national news#latest national news

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trains Between Stations

Trains Between Stations

All the information that the user needs about all these different kinds of trains that run between stations is now within his/her command. Our simple NDTV Rail Beeps search will bring right in front of your screen, the details of the number of trains running, operative days of the trains, train timings and a lot many more options. The simple NDTV Rail Beeps is based on real time data from the Indian Railways with results that are constantly updated.

The NDTV Rail Beeps search is based from the latest Indian Railways and IRCTC schedules. With accurate data of different train timetables, it will help the user plan his/her travel much more efficiently.

Find Trains Between Stations Quickly

The process to find the trains between stations is, as mentioned before, very simple. Using NDTV Rail Beeps search makes the entire process of finding where to travel, how to travel and when to travel, very simple. Here is how to go about it in just three simple steps.

STEP 1: There are two search boxes. The user has to simply type the names of the two stations in them.

STEP 2: When you write the name of the station, a drop-down menu will provide you with one or more options of the station name and the station code. Simply select the station you want. For Ex: On typing New Delhi, the drop-down menu will display the option: “NEW DELHI (NDLS)”.

STEP 3: After selecting the station name and station code of two stations, simply select the date of journey and then hit the “Enter” key on your keyboard or click on the “Search Train” option.

Search Results

After you complete the above process, the following search results will appear:

1. Number of trains running between the two selected stations

2. Indian Railway train codes/ Train Numbers

3. Train names

4. The train station of origin

5. Scheduled Departure time

6. Scheduled Arrival time

7. The Weekly Schedule of the trains (Number of days the trains run in a week)

8. The Travel Class: AC, Chair Car, Sleeper, etc

With the increasing demand of getting information at your fingertips, here is the amazing ability to see trains between stations at your command, whenever you need it. And the whole process to get the information you want is very simple and completely hassle-free. The Indian Railways is the fourth largest railway networks in the world with 1,15,000 kms of tracks over a 65,000 kms of distance and a revenue of around Rs 1.7 trillion. All of this because around 20 million passengers travel every day in the Indian railways!

Not only this, but in 2015-16, an average of 13,313 passenger trains ran daily. The 13,313 trains were estimated to have carried around an estimated 22 million passengers every single day. The Indian Railways also have over 70,000 passenger coaches with more than 11,000 locomotives.

To cover so much ground, trains travel all across India between many stations. Because of the vast network of railways, there is a huge demand to travel. And since there is a huge demand to travel in today’s age of rapid advancement in technology, a huge information database for trains between stations is the need of the hour. Especially a reliable database that has information on all the different trains between stations all across India and which is also easily accessible without any difficulties.

Now, Information Enquiry For All National Trains Is Easy

What is also important is to get to know the trains between all the stations in an easy, user-friendly manner, as over-complicated steps should not turn away the user. Fortunately, with the way technology has progressed, gone are the times when one had to physically go to a railway station to find out information about all the different trains or even use phones to call up the railway stations and ask for information.

With the spread of the internet, it has now become extremely easy to access all the information one needs on all the important trains running through the entire railway network.

Database Of Trains In Indian Railways

There are a vast number of trains that run between important stations. All metropolitan cities as well as almost all other cities, towns and villages are covered in the entire length and breadth of the country’s railway network!

There are also a vast number of trains that run across the country every day. It is important that the database accurately covers all the trains that run across all the different stations. Any small error can lead to a huge loss for the user, which is unacceptable.

There are a large number of trains that are searched about daily by users who need to travel between many important stations. The many types of trains are the Rajdhani, Superfast trains, Duronto, Shatabdi, passenger trains, mail express trains and the local trains that run in the metro city of Mumbai.

Mumbai Local

The Mumbai Local trains are the most famous of the local trains because of the large volume of people who travel across the length and breadth of the huge city of Mumbai. It is also the oldest mode of transport in the mega city of Mumbai.

Luxury Trains

Apart from local trains and passenger trains, there are luxury trains too. Those passengers who wish to avail premium travel would also like information on such trains. These trains have a special travel circuit and they travel between important stations where there are many different tourist spots and they also stop at many different heritage spots as well.

Some of these luxury trains include the Maharajas Express, the Golden Chariot, the Deccan Odyssey and perhaps the most famous of all the luxury trains, the Palace On Wheels.

The trains are specially designed to reflect the utmost luxury to the passengers who choose to travel on these trains.

Garib Rath

Apart from the luxury trains, the Garib Rath is also a special, one-of-a-kind train. These trains have reduced fares to make train travel more affordable for those less fortunate. The Garib Rath trains are also super fast trains which also have Air Conditioned coaches as well, so that passengers travel with the least inconvenience.

The Garib Rath beats the speeds of some express trains and some super fast trains too!

Duronto Express

This is one of the fastest trains in India. The Duronto Express trains are parallel to the Rajdhani and Shatabdi trains when it comes to their speed! The Duronto trains have a special ability in that they are only connected to all the major capital cities of the country and the fact that they are long-distance trains allows them to complete long distances between major stations in very short times.

The NDTV database of trains between stations includes information on all of the above types of trains and the important stations that connect them.

Some Interesting Facts Of Trains Between Stations

With such a vast network of railway lines, there are a number of interesting facts about the different trains between stations that are sure to be of interest.

For example, the shortest distance that is covered between two successive stations is just 3 kms. The 3 kms long distance is between Nagpur station and Ajni station.

In contrast, the longest distance that is covered by a train is 4,273 kms. The distance is between the stations of Dibrugarh and Kanyakumari and the train that covers it is called the Vivek Express.

The station with the longest name is “Venkatanarasimharajuvaripeta” in Andhra Pradesh while the one with the smallest station name is “Ib” in Odisha.

The Trivandrum-Hazrat Nizamuddin Rajdhani Express train covers a distance of 528 kms without stopping!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chhatrapur, Ganjam

Chhatrapur, Ganjam

Ganjam district headquarters subdivision Chhatrapur is the main sub-division and main city of Ganjam district in the Indian state of Odisha. There are 2 railway stations here. Geography As of 2011 India census, Chhatrapur had a population of 20,288 (the second largest city in the district) after Ganjam. Males constitute 51% and females 49%. Chhatrapur has an average literacy rate of 89%, higher than the national average of 59.5%; With 85% male literacy and 73% female literacy, 10% of the population is under 6 years of age.

History-- The Ganjam region was part of the ancient Kalinga Empire, which was occupied by King Ashoka in 261 AD, during which time it was the main southern and eastern route for transportation. A large number of black elephants attracted King Ashoka to attack Kalinga. The district was renamed the Old Township on the north bank of the Rushikulia River, and the European Fortress of Ganjam. In 1757 it was the bus of the French commander, who went to Ganjam to pay homage to the head of the empire. It was the English who finally defeated the French at Deccan and annexed Ganjam in 1759. The modern Ganjam Madras Presidency was excavated in Vizag district on March 31, 1936. Ganjam district separated from the President of Madras and formed part of the newly formed Odisha from 1.4.1936. The reorganized district comprises the entire Ghumsar, Chatpur and Baliguda divisions, part of the old Berhampur taluk, part of the old Ichapur taluk, part of the Parlakhemundi plains and the entire Parlakhemundi agency area of the old Chicakola section. In 1992, after the reorganization of the district by district of the Government of Odisha, 7 blocks of Parlakhemundi subdivision were separated and the new district of Gajapati was formed and 3 subdivisions, 22 blocks and 18 urban areas remained in Ganjam district.

Transportation-- Chhatrapur is the commercial capital of the state and the gateway to the southern [Odisha], and it has a well-developed transport network. All express trains of Indian Railways are stopped here Howrah is well connected to the Madras highway so all the luxury buses pass through

Road-- Chhatrapur city is connected to the National Highway NH-16 (Chennai - Kolkata), NH-59 ([[Kharia] three-wheeled auto taxi) is the most important mode of transportation in the city. Taxis are also flying on the city's roads. In partnership, Ganjam Urban Transport Services Limited (GUTSL) has entered into a one-year contract to operate bus services for a city.

Rail-- Chhatrapur Railway Station is located on the east coast railway line, which is one of the major routes connecting India's two metros, Kolkata and [Chennai]. It is located directly in New Delhi, Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhubaneswar, Berhampur, Chennai, [Cuttack], Mumbai, Nagpur, Pune, [Puri]], Vishakhapatnam, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Raipur, Sambalpur and many more [India]. Bhubaneswar - Chhatrapur Connection (DMU) is a popular connection to reach the capital Bhubaneswar Chhatrapur has two railway stations; They are Chhatrapur Station CAP and Chhatrapur Court Station which is a passenger halt

0 notes

Text

New Railway Lines to Boost Connectivity in Tribal Districts: Dr. Dinesh Sarangi

60 km track approved after 47-year struggle; to benefit Jharkhand, Odisha, Bengal Former Health Minister Dr. Dinesh Kumar Sharangi welcomed the approval of key railway connections for tribal-dominated districts. JAMSHEDPUR – The government has approved several crucial railway connections, including the 60 km Budhamara-Chakulia line, benefiting tribal districts in Jharkhand, Odisha, and West…

#जनजीवन#Budhamara-Chakulia railway line#Dr. Dinesh Kumar Sharangi#East Singhbhum development#Indian Railways expansion#Jharkhand railway connectivity#Keonjhar transport infrastructure#Life#Mayurbhanj railway connection#Odisha infrastructure projects#Shimlipal Biosphere tourism#tribal district development

0 notes

Text

Frontier of East Coast Railway needs to be redrawn

With the Waltair Division of East Coast Railway going to the new South Coast Railway, there is now widespread talk about injustice to Odisha. The matter is important enough to warrant a detailed and dispassionate analysis. Minister’s assurance that railway lines within Odisha under the Waltair Division would remain under the East Coast Railway, however, does not address the issue fully. While it…

0 notes

Photo

Latest News from https://is.gd/FJBOcJ

Dhaka Metro | L&T bags contract worth Rs 3,191 crore for construction of metro line

New Delhi: L&T Construction (a subsidiary of L&T Group of companies) has secured a contract of Rs 3,191 crore for the construction of a railway line of Dhaka Metro. The company gave this information today. The joint venture of L&T Construction and Japan’s Marubani Corporation got this contract in the international bidding process.

The company told the Bombay Stock Exchange that L&T Construction got a contract of Rs 3,191 crore for the electrical and mechanical system package of Dhaka Mass Rapid Transit Development Project (MRT-Line 6). They got this contract from the Dhaka Mass Transit Company (DMTC) which includes construction and design of Line-6, first metro route of the the mass rapid transit system in Bangladesh. Japan International Corporation Agency (JICA) is offering funding for this project.

L&T Construction has also received contracts worth Rs 4,033 crore in the domestic market. L&T Construction’s building and factory business got orders worth Rs 4,033 crore. This includes construction and design contracts for 1,125 residential towers in Visakhapatnam, Prakasam, Guntur and Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh.

In addition, orders for design and construction of cement plant in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh were also received. L&T has also got a contract to establish Cancer Institute in Bihar’s capital Patna, along with the supply, installation and commissioning of medical equipment.

Consortium of L&T Hydrocarbon Engineering has got contract to set up two compost plants from Hindustan Fertilizers and Chemicals Limited. L&T Hydrocarbon Engineering, a wholly owned subsidiary of Larsen & Toubro Ltd, has bagged two important contracts from TechnipFMC with Hindustan Fertilizers and Chemicals Limited (HURL).

HURL is a joint venture of Indian Oil, NTPC, Coal India, Fertilizer Corporation of India Limited and HFCL. The project involves engineering, procurement, construction and commissioning of two fertilizer plants in Barauni (Bihar) and Sindri (Jharkhand). The Rs 3,800-crore contract includes 2,200 TPD ammonia plants. Work will be started simultaneously on both projects.

Click here to see more https://is.gd/FJBOcJ

#Dhaka Metro#HURL#L&T#Metro & Railway Construction#Metro rail contract#Industry News#International#Metro Rail#Metro Rail Projects#Tender & Contracts

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://techcrunchapp.com/news-updates-live-technology-is-helping-us-deal-with-agricultural-challenges-says-pm-modi/

News Updates Live: Technology is helping us deal with agricultural challenges, says PM Modi

!1 New UpdateClick here for latest updates

Congress writes to Facebook CEO again

The Congress’ letter to Zuckerberg came over an article in Time magazine, which the opposition party claimed “revealed” more information and “evidence of biases and a quid pro quo relationship” of Facebook India with the Bharatiya Janata Party.

Tour De France to go ahead, despite COVID-19 concerns

The number of daily cases in France has been rising steadily in recent weeks, casting a menacing shadow over the three-week event which is starting nine weeks later than originally scheduled.

Single voter list for LS, assembly, local body polls?

At present, the Election Commission prepares the electoral roll or voter list for Lok Sabha and assembly polls. The state election commissions, which are altogether separate bodies as per constitutional provisions, hold elections for local bodies such as municipalities and panchayats in their respective states based on their own voter lists.

An update from the Health Minister:

Only 0.29% of COVID-19 patients are on ventilators, 1.93% on ICU & 2.88% of cases are on oxygen support. More than 9 lakh samples were tested in the last 24 hours.

BSF finds Pakistani tunnel

The sandbags have proper markings of Pakistan, which clearly shows that it was dug with proper planning & engineeri… https://t.co/EPDafnSFVl

— ANI (@ANI) 1598692973000

UP Rajya Sabha polls: Nomination papers of BJP leader Syed Zafar filed

CM Yediyurappa to flag off first RORO train from Bengaluru to Solapur tomorrow

New e-market platform launched to bridge gap between Indian farmers and UAE food industry

The UAE has launched Agriota, a new technology-driven agri-commodity trading and sourcing e-market platform that will bridge the gap between millions of rural farmers in India and the Gulf nation’s food industry.

Upon landing in the UAE, all IPL participants have followed a mandatory testing & quarantine programme. Total of 1,988 RT-PCR COVID tests were carried out between August 20th – 28th. 13 personnel have tested positive of which 2 are players

– Board of Control for Cricket in India

A protest will be lodged with Pakistani authorities, asking to take action against the guilty

– Jammu BSF IG NS Jamwal on the recovery of a tunnel in Samba area of Jammu and Kashmir

We were getting input about the existence of a tunnel in Samba area (of Jammu & Kashmir). A special team found the tunnel yesterday

– Jammu BSF IG NS Jamwal

Meghalaya’s COVID-19 tally rises to 2,248

Affordable rental housing complexes included in list of infrastructure sub sectors

The Centre has included affordable rental housing complexes in the harmonized list of infrastructure sub-sectors.

The department of economic affairs under the ministry of finance issued a notification earlier this week to this effect.

877 newborns,61 pregnant women die in Meghalaya in last four months: Official

At least 61 pregnant women and 877 newborns have died in Meghalaya in the four months starting from April for want of admission to hospitals and also due to lack of medical attention because of diversion of the health machinery to fight COVID-19 pandemic, a senior health department official said.

Puducherry MLA files plea in SC to stall NEET

On behalf of Puducherry government, we filed a writ petition in SC to stall NEET exam. The case has been filed in my name. The petition will be heard by next week. We hope for a good ruling from the SC which will safeguard the student community: R K R Anantharaman, Puducherry MLA

UAE formally ends Israel boycott amid US-brokered deal

The ruler of the United Arab Emirates has issued a decree formally ending the country’s boycott of Israel amid a US-brokered deal to normalize relations between the two countries.

The state-run WAM news agency reported the decree on Saturday, saying it was on the orders of Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the ruler of Abu Dhabi and the Emirates’ leader.

Sushant case: Rhea arrives for CBI questioning for second day

Actress Rhea Chakraborty, who is accused of abetting the suicide of film star Sushant Singh Rajput, reached the DRDO guest house here for the second consecutive day on Saturday for questioning by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), an official said.

Modern technology is helping deal with the challenges related to agriculture. One example of it was how the government used technology to minimize damage caused by locust attack in about 10 States recently

– PM Modi

Financial experts express mixed feelings on RBI’s restructuring package

The loan restructuring package announced by the Reserve Bank of India evoked mixed reactions from experts in the financial sector, as some found it helpful for the tourism industry, while others described the guidelines of the scheme as “restrictive” to the NBFCs.

Tourism Finance Corporation of India MD and CEO Anirban Chakraborty said hotels and the hospitality sector are under the MSME segment in the loan restructuring framework of RBI.

The emergency credit line extended to the borrowers is a good measure to help the sector sustain for the next two years, he said at a webinar organised by Enqube Collaborations on Friday.

Govt implementing several projects to ensure availability of water in drought-prone Bundelkhand region: PM Modi

Jharkhand allows public transport within state; hotels, lodges to reopen in view of JEE/NEET exams

India has controlled spread of locust swarms using modern technologies including drones

– PM Narendra Modi

When we talk about self-reliance in agriculture then it is not limited to self-sufficiency in food grains but encompasses self-reliance of the entire economy of the village

– PM Narendra Modi

West Bengal govt writes to Railway Board, says metro, local train services can be resumed

IIT Kharagpur researchers develop microneedle to administer drug in a painless way

Researchers at IIT Kharagpur have developed a microneedle which is capable of administering large drug molecules in a painless way, a statement issued by the institute said on Saturday.

The Institute’s Department of Electronics and Electrical Communication Engineering has not only reduced the diameter size of the microneedles but also increased the strength so that they do not break while penetrating the skin, it said.

The microneedle can be used even in COVID-19 vaccination in future, besides for insulin delivery, the statement said.

Pak set to reopen educational institutions from mid-September as COVID-19 situation improves

DERC’s power tariff for 2020-21 will add to financial challenges of discoms: TPDDL

The new power tariff announced by the DERC for 2020-21, without any hike in the existing rates, will “substantially increase” the financial “challenges” and “ability” to ensure round-the-clock electricity supply by the discoms in Delhi, a spokesperson of the TPDDL said on Saturday.

The Delhi Electricity Regulatory Commission (DERC) announced the new tariff on Friday, saying no hike was considered due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, the DERC has maintained the tariff at the existing level. However, for the discoms, this tariff order will substantially increase the financial challenges and hence, the ability to ensure 24×7 power supply,” the spokesperson of the Tata Power Delhi Distribution Limited (TPDDL) said.

PM inaugurates Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agricultural University, Jhansi

Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurates the College and Administration Buildings of Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agric… https://t.co/MJfT4xfKk3

— ANI (@ANI) 1598685644000

Flood-like situation in 4 C’garh districts, thousands shifted

Heavy rains battered several parts of Chhattisgarh over the last two days, creating a flood-like situation in some areas of at least four districts and causing rivers, including the Mahanadi, to flow above the danger mark, officials said.

Nearly 12,000 houses in various districts of the state were partially or completely damaged due to the incessant rainfall and thousands of people were shifted to relief camps, they said.

Chinese, Indians constitute 48% of foreign students in US in 2019: Report

Chinese and Indians accounted for 48 per cent of all active foreign students in the US in 2019, according to an official report.

A report on immigration students in US, released on Friday by the Student and Exchange Visitor Programme (SEVP) — a part of the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — said there were 1.52 million active records in SEVIS for F-1 and M-1 students during calendar year 2019, a 1.7 per cent decrease from 2018.

Jammu-Srinagar NH cleared for stranded vehicles after four days closure

Govt making numerous efforts to popularise sports and support sporting talent

– PM Modi

August receives 25 pc more rainfall; highest in 44 years: IMD

Mumbai police will provide protection to Rhea Chakraborty on CBI’s request

Mumbai police will provide protection to Rhea Chakraborty whenever she commutes from her residence to DRDO guest house. This is being done on the request of Central Bureau of Investigation: Mumbai Police official

Odisha floods: 1.5 lakh people affected across 543 villages

Flood situation continues in several parts of Bhadrak district. Additional District Magistrate, Bhadrak says, “1.5 lakh people are affected across 543 villages in the district that are facing flood situation. Over 3,000 people have been evacuated so far.”

Pranab Mukherjee health update

Former President Pranab Mukherjee is being treated for lung infection. His renal parameters have improved. He continues to be in deep coma and on ventilator support. He remains haemodynamically stable: Army Hospital (R&R), Delhi Cantonment

Suresh Raina pulls out of upcoming IPL, says CSK

Suresh Raina returns to India from UAE 'for personal reasons' and will be unavailable for the remainder of the IPL… https://t.co/Au8yee9GtM

— ANI (@ANI) 1598680595000

President Kovind virtually confers the National Sports and Adventure Awards 2020

President Ram Nath Kovind virtually confers the National Sports and Adventure Awards 2020. https://t.co/f0VZoDoz9y

— ANI (@ANI) 1598680174000

Kiren Rijiju defends govt’s decision to confer Sports Awards to record 74 winners

J-K: Seven terrorists neutralised, one surrendered in last 24 hours

Acting on a specific police input, an operation was launched in Zadoora area of Pulwama district by security forces at 1 am on Saturday in which three terrorists were neutralised. A soldier, who was critically injured in the encounter succumbed to his injuries, according to a Public Relations Officer of Defence, Srinagar. Incrimination materials including arms and ammunition were seized from the encounter site.

Malaysia extends ban on foreign tourists

Malaysia has extended its pandemic movement restrictions including a ban on foreign tourists until the end of the year.

Hockey veterans to attend the National Sports Award Ceremony

Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Awardee Rani Rampal, who is also Captain of Indian Women’s Hockey Team & Arjuna Awardee, Hockey player Akashdeep Singh leave for Sports Authority of India (SAI) Centre in Bengaluru to attend the National Sports Award Ceremony that is being held virtually.

Trump to head to Louisiana as Hurricane Laura cleanup starts

The U.S. toll from the Category 4 hurricane stood at 14 deaths, with more than half of those killed by carbon monoxide poisoning from the unsafe operation of generators. President Donald Trump plans on Saturday to tour the damage in Louisiana and neighbouring Texas.

Pandemic reinforced need to be physically fit, mentally strong

– M Venkaiah Naidu on National Sports Day

Kamala Harris pledges to rejoin the Paris Climate agreement and re-enter Iran nuke deal if voted to power

Uttarakhand BJP Chief Bansidhar Bhagat tests positive for COVID19

UP Congress leader demands expulsion of Ghulam Nabi Azad from party

Congress leader Naseeb Pathan in Uttar Pradesh on Friday said the party should expel Ghulam Nabi Azad who is among 23 signatories to a letter which called for an overhaul of the organisation.

Indian heritage WWII spy Noor Inayat Khan gets honoured with blue plaque in London

Telangana reports 2.7K Covid-19 cases, recovery still lower than national average

Will FM answer how to describe mismanagement of economy before pandemic

– P Chidambaram

Single-day spike of 76,472 infections, 1,021 fatalities push India’s COVID-19 caseload to 34,63,972, death toll to 62,550: Health Ministry

Party election to pick PM Abe’s successor around Sept. 15, media say

Today, on National Sports Day, we pay tributes to Major Dhyan Chand, whose magic with the hockey stick can never be forgotten. This is also a day to laud the outstanding support given by the families, coaches and support staff towards the success of our talented athletes

– PM Narendra Modi

The water level of Yamuna River recorded at Delhi’s Old Yamuna Bridge was 204.26 metres at 8 am today

Three militants, one soldier killed in encounter in J-K’s Pulwama

Prize money on sports awards to be increased: Kiren Rijiju

We’ve taken a decision to increase prize money for sports & adventure awards. Prize money for sports awards has already been increased. Prize money for Arjuna Award & Khel Ratna Award has been increased to Rs 15 lakhs & Rs 25 lakhs respectively: Union Sports Minister Kiren Rijiju

Odisha: Examination cities to remain free from lockdown

There will be no lockdown or shutdown in force in the examination cities in Odisha from 30th August and 7th September and from 12th September and 14th September: State Government

Pulwama encounter update:

One soldier who was critically injured has succumbed to his injuries in an encounter that started last night in Zadoora area of Pulwama. Joint operation in progress: PRO Defence, Srinagar

Black Panther star Chadwick Boseman dies of cancer at 43

China’s Wuhan says all schools to reopen on Tuesday

var objSec = template: 'liveblog', msid:'77814983', secNames: ['news'],secIds:['2147477890','1715249553'];

var tmplName = tpName = 'liveblog',lang = '',nav_sec1,newHookId,subsec1_value,subsec1_common = '1715249553',newHookId2,subsec2_value,subsec2_common = '0'; var objVc = version_on:'20200829164304',js_comments:'111',js_googleslock:'782',js_googlelogin:'21',js_common_buydirect:'749',js_bookmark:'17',js_login:'39',js_datepicker:'2',js_electionsmn:'22',js_push:'53',css_buydirect:'14',js_tradenow:'14',js_commonall:'117',lib_login:'https://jssocdn.indiatimes.com/crosswalk/jsso_crosswalk_legacy_0.5.9.min.js',live_tv:'"auto_open": 0, "play_check_hour": 12, "default_tv": "0"',global_cube:'0',global_cube_wap:'0',global_cube_wap_url:'https://m.economictimes.com/iframe_cube.cms',site_sync:'0',amazon_bidding:'1',fan_ads:'0',trackAdCode:'0',ajaxError:'1',oauth:'oauth',planPage:'https://prime.economictimes.indiatimes.com/plans',subscriptions:'subscriptions',krypton:'kryptonp'; var objDim = d52:'nature_of_content',d10:'user_login_status_hit',d54:'content_shelf_life',d53:'content_target_audience',d12:'tags_meta_keyword',d56:'degree_of_conten',d11:'content_theme_the_primary_tag',d55:'content_tone',d14:'special_coverage',d13:'article_publish_time',d16:'video',d15:'audio',d59:'show_paywall_final',d61:'paywall_probability',d60:'paywall_score',d63:'paid_articles_read',d62:'eligibility_paywall_rule',d65:'bureau_articles_read',d20:'platform',d64:'free_articles_read',d23:'author_id',d67:'loyalty',d66:'article_length',d25:'page_template',d24:'syft_initiate_page',d68:'paywall_hits',d27:'site_sub_section',d26:'site_section',d29:'section_id',d28:'prime_deal_code',d32:'prime_article_read_before_syft',d34:'content_age',d33:'prime_article_read_before_success',d36:'sign_in_initiation_position',d35:'subscription_method_hit',d37:'user_subscription_status',d1:'et_product',d2:'blocker_type',d3:'user_login_status',d4:'agency',d5:'author',d6:'cms_content_publishing_type',d7:'content_personalisation_level',d8:'article_publish_date',d9:'sub_section_name',d40:'freeread',d45:'prime_hp_ui_template',d47:'prime_hp_ui_content_b_color',d46:'prime_hp_ui_content_size',d49:'syft_initiate_position',d48:'content_msid',d50:'signin_initiate_page';var serverTime = '08.29.2020 16:44:03';var WRInitTime=(new Date()).getTime(); (function () if (self !== top) var e = function (s) return document.getElementsByTagName(s); e("head")[0].innerHTML = '

*display:none;

'; setTimeout(function () e("body")[0].innerHTML = ''; var hEle = e("html")[0]; hEle.innerHTML = 'economictimes.indiatimes.com'; hEle.className = ''; top.location = self.location; , 0);)();

_log = window.console && console.log ? console.log : function () ; if(window.localStorage && localStorage.getItem('temp_geolocation')) var geolocation = localStorage.getItem('temp_geolocation'); // Creating Elements for IE : HTML 5 and cross domain checks (function () var elem = ["article", "aside", "figure", "footer", "figcaption", "header", "nav", "section", "time"]; for(var i=0; i -1) window[disableStr + '-' + gaProperty] = true;

ga('set', 'anonymizeIp', true); ga('create', gaProperty, 'auto', 'allowLinker': true); ga('require', 'linker'); ga('linker:autoLink', ['economictimes.com']); ga('require', 'displayfeatures'); window.optimizely = window.optimizely || []; window.optimizely.push("activateUniversalAnalytics"); ga('require', 'GTM-KS2SX8K');

(function () )()

customDimension.dimension25 = "liveblog"; customDimension.dimension26 = "News"; customDimension.dimension27 = "News/"; customDimension.dimension29 = "1715249553"; customDimension.dimension48 = "77814983"; ga('send', 'pageview', customDimension); ga('create', 'UA-5594188-55', 'auto','ETPTracker'); //ETPrime GA

(function (g, r, o, w, t, h, rx) function () []).push(arguments) , g[t].l = 1 * new Date(); g[t] = g[t] )(window, document, 'script', 'https://static.growthrx.in/js/v2/web-sdk.js', 'grx'); grx('init', 'gf999c70d'); var grxDimension = url: window.location.href, title : document.title, referral_url : document.referrer;

if(window.customDimension && window.objDim) for(key in customDimension) var dimId = 'd' + key.substr(9, key.length); if(objDim[dimId] && customDimension[key]) grxDimension[objDim[dimId]] = customDimension[key];

var subsStatus = 'Free User'; var jData = JSON.parse(localStorage.getItem('jStorage')); function getCookie(n) var ne = n + "=", ca = document.cookie.split(';');for (var i=0;i -1) subsStatus = 'Expired User'; else if (grx_userPermission.indexOf("subscribed") > -1 && grx_userPermission.indexOf("cancelled_subscription") > -1 && grx_userPermission.indexOf("can_buy_subscription") > -1) subsStatus = 'Paid User - In Trial'; else if(grx_userPermission.indexOf("subscribed") > -1) subsStatus = 'Paid User'; else if(grx_userPermission.indexOf("etadfree_subscribed") > -1) subsStatus = 'Ad Free User'; catch (e) else grxDimension['user_login_status'] = 'NONLOGGEDIN'; grxDimension['user_subscription_status'] = subsStatus; )()

grx('track', 'page_view', grxDimension);

if(geolocation && geolocation != 5 && (typeof skip == 'undefined' || typeof skip.fbevents == 'undefined')) !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', 'https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); fbq('init', '338698809636220'); fbq('track', 'PageView');

var _comscore = _comscore || []; _comscore.push( c1: "2", c2: "6036484");

if(geolocation && geolocation != 5) (function() var s = document.createElement('script'), el = document.getElementsByTagName("script")[0]; s.async = true; s.src = (document.location.protocol == "https:" ? "https://sb" : "http://b") + ".scorecardresearch.com/beacon.js"; el.parentNode.insertBefore(s, el); )();

if(geolocation && geolocation != 5)

(function() function pingIbeat() window._pg_endpt=(new Date()).getTime(); var e = document.createElement('script'); e.setAttribute('language', 'javascript'); e.setAttribute('type', 'text/javascript'); e.setAttribute('src', "https://agi-static.indiatimes.com/cms-common/ibeat.min.js"); document.head.appendChild(e); if(typeof window.addEventListener == 'function') window.addEventListener("load", pingIbeat, false); else var oldonload = window.onload; window.onload = (typeof window.onload != 'function') ? pingIbeat : function() oldonload(); pingIbeat(); ;

)();

0 notes

Text

New world news from Time: How the Pandemic Is Reshaping India

With a white handkerchief covering his mouth and nose, only Rajkumar Prajapati’s tired eyes were visible as he stood in line.

It was before sunrise on Aug. 5, but there were already hundreds of others waiting with him under fluorescent lights at the main railway station in Pune, an industrial city not far from Mumbai, where they had just disembarked from a train. Each person carried something: a cloth bundle, a backpack, a sack of grain. Every face was obscured by a mask, a towel or the edge of a sari. Like Prajapati, most in the line were workers returning to Pune from their families’ villages, where they had fled during the lockdown. Now, with mounting debts, they were back to look for work. When Prajapati got to the front of the line, officials took his details and stamped his hand with ink, signaling the need to self-isolate for seven days.

Atul Loke for TIME

After Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared on national television on March 24 to announce that India would go under lockdown to fight the coronavirus, Prajapati’s work as a plasterer for hire at construction sites around Pune quickly dried up. By June, his savings had run out and he, his wife and his brother left Pune for their village 942 miles away, where they could tend their family’s land to at least feed themselves. But by August, with their landlord asking for rent and the construction sites of Pune reopening, they had no option but to return to the city. “We might die from corona, but if there is nothing to eat we will die either way,” said Prajapati.

As the sun rose, he walked out of the station into Pune, the most infected city in the most infected state in all of India. As of Aug. 18, India has officially recorded more than 2.7 million cases of COVID-19, putting it third in the world behind the U.S. and Brazil. But India is on track to overtake them both. “I fully expect that at some point, unless things really change course, India will have more cases than any other place in the world,” says Dr. Ashish Jha, director of Harvard’s Global Health Institute. With a population of 1.3 billion, “there is a lot of room for exponential growth.”

Read More: India’s Coronavirus Death Toll Is Surging. Prime Minister Modi Is Easing Lockdown Anyway

The pandemic has already reshaped India beyond imagination. Its economy, which has grown every year for the past 40, was faltering even before the lockdown, and the International Monetary Fund now predicts it will shrink by 4.5% this year. Many of the hundreds of millions of people lifted out of extreme poverty by decades of growth are now at risk in more ways than one. Like Prajapati, large numbers had left their villages in recent years for new opportunities in India’s booming metropolises. But though their labor has propelled their nation to become the world’s fifth largest economy, many have been left destitute by the lockdown. Gaps in India’s welfare system meant millions of internal migrant workers couldn’t get government welfare payments or food. Hundreds died, and many more burned through the meager savings they had built up over years of work.

Now, with India’s economy reopening even as the virus shows no sign of slowing, economists are worried about how fast India can recover—and what happens to the poorest in the meantime. “The best-case scenario is two years of very deep economic decline,” says Jayati Ghosh, chair of the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. “There are at least 100 million people just above the poverty line. All of them will fall below it.”

Atul Loke for TIMERajkumar Prajapati, third from right, gives his family’s details to local officials at the train station in Pune on Aug. 5.

Atul Loke for TIMEThe Tadiwala Chawl area of Pune emerged as a COVID-19 hotspot.

Atul Loke for TIMEWorkers from the Pune Municipal Corporation spray disinfectant in the Tadiwala Chawl area.

In some ways Prajapati, 35, was a lucky man. He has lived and worked in Pune since the age of 16, though like many laborers, he regularly sends money home to his village and returns every year to help with the harvest. Over the years, his remittances have helped his father build a four-room house. When the lockdown began, he even sent his family half of the $132 he had in savings. The $66 Prajapati had left was still more than many had at all, and enough to survive for three weeks. His landlord let him defer his rent payments. Two weeks into the lockdown, when Modi asked citizens in a video message to turn off their lights and light candles for nine minutes at 9 p.m. in a show of national solidarity, Prajapati was enthusiastic, lighting small oil lamps and placing them at shrines in his room and outside his door. “We were very happy to do it,” he said. “We thought that perhaps this will help with corona.”

Other migrant workers weren’t so enthusiastic. For those whose daily wages paid for their evening meals, the lockdown had an immediate and devastating effect. When factories and construction sites closed because of the pandemic, many bosses—who often provide their temporary employees with food and board—threw everyone out onto the streets. And because welfare is administered at a state level in India, migrant workers are ineligible for benefits like food rations anywhere other than in their home state. With no food or money, and with train and bus travel suspended, millions had no choice but to immediately set off on foot for their villages, some hundreds of miles away. By mid-May, 3,000 people had died from COVID-19, but at least 500 more had died from “distress deaths” including those due to hunger, road accidents and lack of access to medical facilities, according to a study by the Delhi-based Society for Social and Economic Research. “It was very clear there had been a complete lack of planning and thought to the implications of switching off the economy for the vast majority of Indian workers,” says Yamini Aiyar, president of the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi think tank.

One migrant worker who decided to make the risky journey on foot was Tapos Mukhi, 25, who set off from Chiplun, a small town in the western state of Maharashtra, toward his village in the eastern state of Odisha, over 1,230 miles away. He had tried to work through the lockdown, but his boss held back his wages, saying he did not have money to pay him immediately. Mukhi took another job at a construction site in June, but after a month of lifting bricks and sacks of cement, a nail went through his foot, forcing him to take a day off. His supervisor called him lazy and told him to leave without the $140 he was owed. On Aug. 1, he walked for a day in the pouring monsoon rain with his wife and 3-year-old daughter, before a local activist arranged for a car to Pune. “We had traveled so far from our village to work,” said Mukhi, sitting on a bunk bed in a shelter in Pune, where activists from a Pune-based NGO had given him and his family train tickets. “But we didn’t get the money we were owed and we didn’t even get food. We have suffered a lot. Now we never want to leave the village again.”

Although Indian policymakers have long been aware of the extent to which the economy relies on informal migrant labor like Mukhi’s—there are an estimated 40 million people like him who regularly travel within the country for work—the lockdown brought this long invisible class of people into the national spotlight. “Something that caught everyone by surprise is how large our migrant labor force is, and how they fall between all the cracks in the social safety net,” says Arvind Subramanian, Modi’s former chief economic adviser, who left government in 2018. Modi was elected in 2014 after a campaign focused on solving India’s development problems, but under his watch economic growth slid from 8% in 2016 to 5% last year, while flagship projects, like making sure everyone in the country has a bank account, have hit roadblocks. “The truth is, India needs migration very badly,” Subramanian says. “It’s a source of dynamism and an escalator for lots of people to get out of poverty. But if you want to get that income improvement for the poor back, you need to make sure the social safety net works better for them.”

Atul Loke for TIMEA doctor waits for a dose of remdesivir while a nurse attends to a newly admitted COVID-19 patient at Aundh District Hospital in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEAfter her condition improved, a COVID-19 patient is helped into a wheelchair so she can be transferred from the intensive-care unit to an observation ward.

Atul Loke for TIMEA young worker dressed in personal protective equipment sweeps the floor of the intensive-care unit.

The wide-scale economic disruption caused by the lockdown has disproportionately affected women. Because 95% of employed women work in India’s informal economy, many lost their jobs, even as the burden remained on them to take care of household responsibilities. Many signed up for India’s rural employment scheme, which guarantees a set number of hours of unskilled manual labor. Others sold jewelry or took on debts to pay for meals. “The COVID situation multiplied the burden on women both as economic earners and as caregivers,” says Ravi Verma of the Delhi-based International Center for Research on Women. “They are the frontline defenders of the family.”

But the rural employment guarantee does not extend to urban areas. In Dharavi, a sprawling slum in Mumbai, Rameela Parmar worked as domestic help in three households before the lockdown. But the families told her to stop coming and held back her pay for the last four months. To support her own family, she was forced to take daily wage work painting earthen pots, breathing fumes that make her feel sick. “People have suffered more because of the lockdown than [because of] corona,” Parmar says. “There is no food and no work—that has hurt people more.”

Girls were hit hard too. For Ashwini Pawar, a bright-eyed 12-year-old, the pandemic meant the end of her childhood. Before the lockdown, she was an eighth-grade student who enjoyed school and wanted to be a teacher someday. But her parents were pushed into debt by months of unemployment, forcing her to join them in looking for daily wage work. “My school is shut right now,” said Pawar, clutching the corner of her shawl under a bridge in Pune where temporary workers come to seek jobs. “But even when it reopens I don’t think I will be able to go back.” She and her 13-year-old sister now spend their days at construction sites lifting bags of sand and bricks. “It’s like we’ve gone back 10 years or more in terms of gender-equality achievements,” says Nitya Rao, a gender and development professor who advises the U.N. on girls’ education.

In an attempt to stop the economic nosedive, Modi shifted his messaging in May. “Corona will remain a part of our lives for a long time,” he said in a televised address. “But at the same time, we cannot allow our lives to be confined only around corona.” He announced a relief package worth $260 billion, about 10% of the country’s GDP. But only a fraction of this came as extra handouts for the poor, with the majority instead devoted to tiding over businesses. In the televised speech announcing the package, Modi spoke repeatedly about making India a self-sufficient economy. It was this that made Prajapati lose hope in ever getting government support. “Modiji said that we have to become self-reliant,” he said, still referring to the Prime Minister with an honorific suffix. “What does that mean? That we can only depend on ourselves. The government has left us all alone.”

By the time the lockdown began to lift in June, Prajapati’s savings had run out. His government ID card listed his village address, so he was not able to access government food rations, and he found himself struggling to buy food for his family. Three times, he visited a public square where a local nonprofit was handing out meals. On June 6, he finally left Pune for his family’s village, Khazurhat. He had been forced to borrow from relatives the $76 for tickets for his wife, brother and himself. But having heard the stories of migrants making deadly journeys back, he was thankful to have found a safe way home.

Atul Loke for TIMEKashinath Kale’s widow, Sangeeta, flanked by her sons Akshay, left, and Avinash, holds a framed portrait of her late husband outside their home in Kalewadi, a suburb of Pune. Kale, 44, died from COVID-19 in July as the family desperately tried to find a hospital bed with a ventilator.

Meanwhile, the virus had been spreading across India, despite the lockdown. The first hot spots were India’s biggest cities. In Pune, Kashinath Kale, 44, was admitted to a public hospital with the virus on July 4, after waiting in line for nearly four hours. Doctors said he needed a bed with a ventilator, but none were available. His family searched in vain for six days, but no hospital could provide one. On July 11, he died in an ambulance on the way to a private hospital, where his family had finally located a bed in an intensive-care unit with a ventilator. “He knew he was going to die,” says Kale’s wife Sangeeta, holding a framed photograph of him. “He was in a lot of pain.”

By June, almost every day saw a new record for daily confirmed cases. And as COVID-19 moved from early hot spots in cities toward rural areas of the country where health care facilities are less well-equipped, public-health experts expressed concern, noting India has only 0.55 hospital beds per 1,000 people, far below Brazil’s 2.15 and the U.S.’s 2.80. “Much of India’s health infrastructure is only in urban areas,” says Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the D.C.-based Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy. “As the pandemic unfolds it is moving into states which have very low levels of testing and rural areas where the public-health infrastructure is weak.”

Read More: India Is the World’s Second-Most Populous Country. Can It Handle the Coronavirus Outbreak?

When he arrived back in his village of Khazurhat, Prajapati’s neighbors were worried he might have been infected in Pune, so medical workers at the district hospital checked his temperature and asked if he had any symptoms. But he was not offered a test. “While testing has been getting better in India, it’s still nowhere near where it needs to be,” says Jha.

Nevertheless, Modi has repeatedly touted India’s low case fatality rate—the number of deaths as a percentage of the number of cases—as proof that India has a handle on the pandemic. (As of Aug. 17 the rate was 1.9%, compared with 3.1% in the U.S.) “The average fatality rate in our country has been quite low compared to the world … and it is a matter of satisfaction that it is constantly decreasing,” Modi said in a televised videoconference on Aug. 11. “This means that our efforts are proving effective.”

Atul Loke for TIMEParents keep their child still while a health care worker takes a nasal swab for a COVID-19 test at a school in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEA health care worker executes a rapid antigen COVID-19 test in the local school of Dhole Patil in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEA health care worker checks a woman’s temperature and oxygen saturation in the Dhole Patil slum on Aug. 10.

But experts say this language is dangerously misleading. “As long as your case numbers are increasing, your case fatality rate will continue to fall,” Jha says. When the virus is spreading exponentially as it is currently in India, he explains, cases increase sharply but deaths, which lag weeks behind, stay low, skewing the ratio to make it appear that a low percentage are dying. “No serious public-health person believes this is an important statistic.” On the contrary, Jha says, it might give people false optimism, increasing the risk of transmission.

Modi’s move to lock down the country in March was met with a surge in approval ratings; many Indians praised the move as strong and decisive. But while other foreign leaders’ lockdown honeymoons eventually gave way to popular resentment, Modi’s ratings remained stratospheric. In some recent polls, they topped 80%.

The reason has much to do with his wider political project, which critics see as an attempt to turn India from a multifaith constitutional democracy into an authoritarian, Hindu-supremacist state. Since winning re-election with a huge majority in May 2019, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political wing of a much larger grouping of organizations whose stated mission is to turn India into a Hindu nation, has delivered on several long-held goals that excite its right-wing Hindu base at the expense of the country’s Muslim minority. (Hindus make up 80% of the population and Muslims 14%.) Last year the government revoked the autonomy of India’s only Muslim-majority state, Kashmir. And an opulent new temple is being built in Ayodhya—a site where many Hindus believe the deity Ram was born and where Hindu fundamentalists destroyed a mosque on the site in 1992. After decades of legal wrangling and political pressure from the BJP, in 2019 the Supreme Court finally ruled a temple could be built in its place. On Aug. 5, Modi attended a televised ceremony for the laying of the foundation stone.

Read More: The Battle for India’s Founding Ideals

Still, before the pandemic Modi was facing his most severe challenge yet, in the form of a monthslong nationwide protest movement. All over the country, citizens gathered at universities and public spaces, reading aloud the preamble of the Indian constitution, quoting Mohandas Gandhi and holding aloft the Indian tricolor. The protests began in December 2019 as resistance to a controversial law that would make it harder for Muslim immigrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, to gain Indian citizenship. They morphed into a wider pushback against the direction of the country under the BJP. In local Delhi elections in February, the BJP campaigned on a platform of crushing the protests but ended up losing seats. Soon after, riots broke out in the capital; 53 people were killed, 38 of them Muslims. (Hindus were also killed in the violence.) Police failed to intervene to stop Hindu mobs roaming around Muslim neighborhoods looking for people to kill, and in some cases joined mob attacks on Muslims themselves, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Atul Loke for TIMEWorkers push the body of a COVID-19 patient into the furnace of Yerawada crematorium in Pune on Aug. 11.

“During those hundred days I thought India had changed forever,” says Harsh Mander, a prominent civil-rights activist and director of the Centre for Equity Studies, a Delhi think tank, of the three months of nationwide dissent from December to March. But the lockdown put an abrupt end to the protests. Since then, the government has ramped up its crackdown on dissent. In June, Mander was accused by Delhi police (who report to Modi’s interior minister, Amit Shah) of inciting the Delhi riots; in the charges against him, they quoted out of context portions of a speech he had made in December calling on protesters to continue Gandhi’s legacy of nonviolent resistance, making it sound instead like he was calling on them to be violent. Meanwhile, local BJP politician Kapil Mishra, who was filmed immediately before the riots giving Delhi police an ultimatum to clear the streets of protesters lest his supporters do it themselves, still walks free. “In my farthest imagination I couldn’t believe there would be this sort of repression,” Mander says.

Read More: ‘Hate Is Being Preached Openly Against Us.’ After Delhi Riots, Muslims in India Fear What’s Next

A pattern was emerging. Police have also arrested at least 11 other protest leaders, including Safoora Zargar, a 27-year-old Muslim student activist who organized peaceful protests. She was accused of inciting the Delhi riots and charged with murder under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, a harsh anti-terrorism law that authorities used at least seven times during the lockdown to arrest activists or journalists. The law is described by Amnesty International as a “tool of harassment,” and by Zargar’s lawyer Ritesh Dubey, in an interview with TIME, as aimed at “criminalizing dissent.” As COVID-19 spread around the country, Zargar was kept in jail for two months, without bail, despite being 12 weeks pregnant at the time of her arrest. Restrictions in place to curb the spread of coronavirus, like not allowing lawyers to visit prisons, have also impacted protesters’ access to legal justice, Dubey says.

“The government used this health emergency to crush the largest popular movement this country has seen since independence,” Mander says. “The Indian Muslim has been turned into the enemy within. The economy has tanked, there is mass hunger, infections are rising and rising, but none of that matters. Modi has been forgiven for everything else. This normalization of hate is almost like a drug. In the intoxication of this drug, even hunger seems acceptable.”

Read More: It Was Already Dangerous to Be Muslim in India. Then Came the Coronavirus

Close to going hungry, Prajapati says the Modi administration has provided little relief for people like him. “If we have not gotten anything from the government, not even a sack of rice, then what can we say to them?” he says. “I don’t have any hope from the government.”

Still a change in government would be too much for Prajapati, a devout Hindu and a Modi supporter, who backs the construction of the temple of Ram in Ayodhya and cheered on the BJP when it revoked the autonomy of Kashmir. “There is no one else like Modi who we can put our faith in,” he says. “At least he has done some good things.”

Prajapati remained in Khazurhat from June until August, working his family’s acre of farmland where they grow rice, wheat, potatoes and mustard. But there was little other work available, and the yield from their farm was not sufficient to support the family. Now $267 in debt to employers and relatives, he decided to return to Pune along with his wife and brother. Worried about reports of rising cases in the city, his usually stoic father cried as he waved him off from the village. On his journey, Prajapati carried 44 lb. of wheat and 22 lb. of rice, which he hoped would feed his family until he could find construction work.

On the evening of his return, Prajapati cleaned his home, cooked dinner from what he had carried back from the village, and began calling contractors to look for work. The pandemic had set him back at least a year, he said, and it would take him even longer to pay back the money he owed. The stamp on his hand he’d received at the station, stating that he was to self-quarantine for seven days, had already faded. Prajapati was planning to work as soon as he could. “Whether the lockdown continues or not, whatever happens we have to live here and earn some money,” he said. “We have to find a way to survive.”

—With reporting by Madeline Roache/London

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2EhqkDC via IFTTT

0 notes