#neo city: japan - the link in osaka day 1

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

191218 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Origin in Osaka Day 1 © P. do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

1 note

·

View note

Text

220625 | NCT 127 performing at the ‘NEO CITY : JAPAN – THE LINK’ in Osaka Day 1

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Independent Working Woman as Deviant in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1867

by Shiho Imai Author: Shiho Imai Title: The Independent Working Woman As Deviant in Todugawa Japan, 1600-1867 Publication info: Ann Arbor, MI: MPublishing, University of Michigan Library 2002 Availability: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information. Source: The Independent Working Woman As Deviant in Todugawa Japan, 1600-1867 Shiho Imai vol. 16, 2002 Issue title: Deviance Subject terms: Asia Domesticity History Prostitution Sexuality URL: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.ark5583.0016.005 As all students of early modern Japan are aware, the ukiyoe ("pictures of the floating world") prominently depict lovers, courtesans, kabuki actors, and various categories of urban entertainers. They also feature a relatively unknown group of women who made their living by selling flowers, tea, and books on the streets of Edo (now Tokyo) and Osaka. These female street peddlers constituted an essential part of the urban scene, both real and imagined. Yet while contemporary artists and writers both scrutinized and celebrated the lives of the women of the "pleasure quarters," they largely ignored the existence of the humble peddlers. [1] To the extent that these peddlers were represented at all, it was in their capacity as sexual beings. When the artists expanded their horizons to include city dwellers, from female street peddlers to maids and wet nurses of merchant households, their depictions were often sensual. [2] Subsumed under the common stereotype of being sexually charged, the differences among the women receded into the background. But if the ukiyoe artists found the slightest resemblance between the courtesans and the working women of Edo, it was not merely the product of their sexual fantasies. It was evidence of an emerging language of "difference" to mark those women who worked beyond the family economy. While the presence of women at work outside the home was nothing new to the Tokugawa period (1600-1867), a clear indication of their growing importance was the emergence of a discourse that cast women's work outside of the household as deviant. To understand how working women came to be seen as deviant, the primary focus here will be on the women of artisan and merchant classes in the cities of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Distinguished from both the samurai and the peasantry, these two classes constituted the lower ranks of the four-tiered social hierarchy in the Tokugawa period. At the top of the four classes was the samurai. This was followed in neo-Confucian theory by the peasant and artisan classes. The merchants found themselves at the bottom of the social order because, in theory, they did no productive work. Although the samurai, the ruling elite, held the merchants and their concern with money in contempt, the townspeople (mainly, merchants and artisans) were financially better off than the peasants. In a period of relative peace and stability like the Tokugawa era, conditions became even more favorable for the merchants. [3] This social class structure determined the ways in which women experienced womanhood in Tokugawa Japan. At the center of the female world was the ie or the extended family - most women lived and worked within the ie. But while the woman of the samurai class was expected to "look to her husband as her lord, and serve him with all worship and reverence," as one moral tract instructed, this kind of subservience to the husband was not necessarily demanded of the women of the lower classes. [4] As historian Anne Walthall has suggested, women in peasant households worked in the fields in much the same way as men. The similarity in the type of work performed allowed for a greater flexibility of gender roles in other areas, such as the participation in social protests. [5] Moreover, historian Kathleen Uno has argued that all members of artisan and merchant households frequently shared productive and reproductive work. The proximity of production and reproduction encouraged men, women, and children alike to contribute to the fundamental goal of family continuity. [6] But if the preservation of the ie took precedence over individual and personal concerns, what of the women who did not marry out? What was the fate of the women who by choice and necessity lived and worked independently of the ie? In this paper, I argue that the emergence of a discourse on deviance that pathologized women's non-domestic work was closely connected to the increasing presence of women who deviated from conventional work patterns that revolved around the maintenance of the ie. As work relations based on ancestral and communal ties gradually gave way to those mediated by money and wages, it made it easier for women to work in areas that had previously been dominated by men. My contention is that the labeling of women who worked beyond the household economy as deviants was a product of this unprecedented commercial expansion. Many scholars of Japanese history in the West have explored the possibilities and limitations of independent working women in Tokugawa Japan through individual case studies: Jennifer Robertson's work on women of the Shingaku (Heart Learning) movement; Patricia Fister's biography of a female poet; and Joyce Chapman Lebra's study of a female sake brewer have contributed to an understanding of the ambivalent roles of working women in artisan and merchant society. [7] More recently, Hitomi Tonomura, Anne Walthall, and Wakita Haruko have translated the works of Japanese scholars such as Yokota Fuyuhiko's study of the period's early encyclopedias on women's work; these scholars have turned to literary sources to reconstruct the ordinary, everyday work roles of women. Given the social and chronological context in which the sources were produced, Yokota has argued that various forms of labor had already been available to women by the mid-seventeenth-century. [8] This essay builds on the research of the scholars above and Japanese-language works by Nishioka Masako and Seki Tamiko, who have made extensive use of contemporary literature that helped to shape the configuration of gender roles. [9] It is an attempt to juxtapose the period's literary production with "real" events and state policy to probe the relationship between ideology and practice. This essay begins by examining some of the urban occupations that were accessible to women. Most of the primary sources used in this paper are literary materials from the Genroku (1688-1703) era. Well-known as an age of brilliant cultural achievement, rooted in the experiences of the expanding bourgeoisie, the Genroku era was a cultural epoch that continued well into the eighteenth century. The celebration of life and sexuality epitomized by ukiyoe art and Genroku literature stood in sharp contrast to the relatively staid cultural productions of the samurai elite. The era's art and fiction may not necessarily mirror the full measure of women's experience, but they reveal the social attitudes about women that are deeply embedded in the narratives. They also reflect the ways in which popular culture shaped expectations of and biases towards women. Genroku culture devoted particular attention to the human body - male and female - as an erotic object and helped essentialize the meaning of gender. [10] It further facilitated the commodification of that essentialized female body with far-reaching implications for women. Modes of representing female bodies in artistic and literary representations echoed the availability of those bodies through channels of public and private prostitution. Next, I will examine the phenomenon that historian Yokota Fuyuhiko has defined as yujo-ka ("prostitute-like"), the blurring of distinctions between the courtesans and laywomen by the early eighteenth century. [11] It was within this context that women who worked independently of the ie came to be identified less through their type of labor than by cultural and spatial markers of deviance. Finally, I will consider the social and economic transformations of the late Tokugawa period as the backdrop to the changing relationship between working women and the state. An analysis of governmental sources, including criminal records and loyalty awards, exposes the role of deviance as a method of social control. The attempt on the part of the Tokugawa bakufu (government) to further distance the sexual labor of the yujo from the productive and reproductive labor of the laywomen sheds light on the continual assessment of women's work. By examining the changing parameters of respectability, I hope to address the fluidity of what constituted deviance for women in early modern Japan and how it evolved over time. Limits of Working Opportunities for Women Within and Beyond the Household There are numerous episodes in writer Ihara Saikaku's (1642-1693) Japanese Family Storehouse (1688) and Five Women who Loved Love (1686) that confirm the presence of women on the shop floor. In Kyoto, a small dyer's shop was run by the husband-wife team of Kikyoya; [12] in the town of Sakata, a man and his wife worked together as brokers of Abumiya; [13] and in Osaka, a cooper and his wife worked day and night, never failing to meet their debts. [14] At first glance, the arbitrary division of household labor suggests that women faced few restrictions governing the character of their work. But limitations on the work roles and space which women could occupy were inherent in this recognition of their work roles. Female labor was all too important to ignore, but women were to be no more than helpmeets in the household economy. The authors of contemporary literature were careful to distinguish women who overstepped these boundaries from the dutiful wives and daughters of merchant households, and they depicted the former far less favorably. The contradictory messages behind society's reliance on female labor were most pronounced in the description of working women that were young, single, and relatively free of direct male supervision. There are many episodes in Tokugawa literature from the Genroku era that emphasize the sexuality of women at work. A case in point is the common portrayal of maids as mischievous young women. Historian Gary Leupp has explained that most artisan and merchant households were able to employ at least one maid-of-all-work by the end of the Tokugawa period. [15] According to Saikaku's Some Final Words of Advice (1694), some of the girls "look just like any other parlor maid but [their] intentions are quite another matter. These stylish women, who fabricate as trustworthy an impression as possible, are actually parlor thieves." [16]Onna daigaku (Greater Learning for Women), the infamous text on womanhood attributed to the Confucian moralist Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714) shared Saikaku's concerns and noted: "Those low-born girls have had no proper education...They are stupid, obstinate, and vulgar in their speech...If a servant girl be altogether too loquacious and bad, she should be speedily dismissed." [17] Ekken claimed that the gossip among female servants was often responsible for the disruption of the household and the decline of the family fortune. Women were also employed as wet nurses and seamstresses in the houses of samurai and well-to-do merchants. As Leupp has explained, employers had little leeway in the selection of wet nurses because of high turnover rates and the constant demand for their services. As evidence, Leupp invokes a description by Saikaku of the circumstances under which the wet nurses were hired: "When you look at the people who take up employment as wet nurses these days, they are generally either people whose marriages are broken up, or servant girls who, unable to get boyfriends, go chasing after men [and get pregnant]." [18] Saikaku's portrayal of the seamstress is also fraught with sexual overtones. The protagonist of Life of an Amorous Woman (1686) attempts a series of occupations to regain her long-lost respectability, one of which is a seamstress, only to slip back into her amorous habits. "From this time forward I was seamstress in name only," she admits; "when I went out on my visits, it was by another form of work that I contrived to make my own living." [19] While it is difficult to assess the accuracy of the ways in which the servants are characterized, the stereotypes also illustrate the employers' concerns over the servants' moral qualities as well as possible acts of violence and sabotage by dissatisfied servants. Most employers incorporated an element of paternalism in their relationship with their servants and provided food, shelter, clothing, and occasional leisure time. In writer Shikitei Sanba's (1776-1822) comedic tale, Ukiyoburo (1809), two maids discuss their mistresses at a bathhouse. "Don't be fooled by her appearance as she is very demanding," one insists. To this the other replies, "If we ever try to live up to their expectations, we'd die of tuberculosis!" Just as the women are about to finish their conversation, they spot a member of the household and immerse themselves in the tub in embarrassment. [20] According to Leupp, the bathhouse was a frequent site where members of nearly all classes met. In addition to random visits to the theater, the bathhouse provided an opportunity for the servants to interact and socialize with each other. [21] However much they were disparaged in popular literature, servant girls were indispensable members of many merchant and samurai households. For the sake of small businesses, domestic service was seen as a proper wage-earning opportunity for women analogous to the cooperation of married women within the ie. As Saikaku himself acknowledged, many were "drawn into a life of service with a view to the future...their main wish being to make prospects for the future as secure as possible." [22] It is likely that domestic service did not impinge on conventional definitions of female labor as long as women's employment was restricted to the home. The final resort for many young women who were either unable or unwilling to work in a household setting was to work in the cities' pleasure quarters. According to historian Cecilia Seigle, the pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara first opened its gate in 1617 to meet the demands of a growing population of wifeless men in Edo. Since it attracted so many new inhabitants, Yoshiwara was suddenly ordered to move to a new location in 1656. The eviction of Yoshiwara was partly due to the city's expansion, but more so to the proximity of the brothels to the center of official activities. Their new site was located beyond the city limits but accessible by road or boat. What is most telling about the character of its operation is that the bakufu was willing to negotiate the terms of the establishment in exchange for operation fees. [23] This reveals the reciprocal relationship between the pleasure quarters and the state and their mutual interest in containing prostitution to a limited area. Since courtesans were confined to the pleasure quarters and hemmed in by many rules and regulations, they constituted a stratum of women specifically "other" than the respectable wives and daughters of urban residents who lived and worked outside the quarters. The courtesans' containment, in turn, justified their labor as necessary evil. As historian Sone Hiromi has suggested, the traffic of women - sold into prostitution by their poverty-stricken parents - and the contractual relationship that bound the courtesans to the quarters reveals how much the female body had taken on the character of merchandise. [24] As long as the courtesan was enclosed within the walls where she could not influence other women, her labor, seen as a commercial transaction, was an accepted part of society. The society of artisan and merchant classes in the cities of Tokugawa Japan, then, did not inhibit women from working altogether. From assisting in family business to working as domestic servants and courtesans, customary means of making a living for women encompassed household labor, wage work and publicly authorized prostitution. But young single women who worked on a contractual basis, whether as waged workers or publicly authorized prostitutes, entered the literary imagination as commodities of sexual desire. To be sure, there is an underlying distrust towards women in general in many of Saikaku's novels. For example, even the ideal wife of a townsman may be "captivated by a delicious love story" or "deluded by the latest dramatic productions." [25] Nevertheless, Saikaku drew a clear line between the temptress and the helpless victim. A woman engaged in the kind of work that removed her from the ie could easily be accused of being overtly sexual. By the early nineteenth century, working women were at once idealized and marginalized, exposing the limitations for women in public. Yujo-ka: Pushing the Limits of Respectability In his reassessment of Confucian moralist Kaibara Ekken's Onna daigaku, historian Yokota Fuyuhiko has argued that implicit in artistic and literary representations of female labor was the possibility of "yujo-ka," or likeness to the courtesans. The repetitive imagery of the female body as commodity confined working women to the status of sexual objects. Not even the women who worked within the accepted bounds of the ie were immune. To guard against the socially dangerous implications of such a possibility, Onna daigaku, according to Yokota, may have been an attempt to deny those sexual connotations attached to women's work by setting the boundaries between respectability and the lack thereof in its cultural and spatial manifestations. Far from subordinating women to the home, Ekken had tried to dissociate the respectable working women from the "real" prostitutes and courtesans. [26] In what instances, then, could yujo-ka or "prostitute-like" status be ascribed to the women of artisan and merchant households? What do those instances tell us about the changing patterns of women's work? What were the implications for wage-earning women whose work occurred outside the ie? As early as the Genroku era, Ekken showed particular concern over the exuberant tastes of the townswomen and stated that "the women of lower classes, ignoring all rules of this nature, behave themselves [in a] disorderly [fashion]...they contaminate their reputations, bring down reproach upon the head of their parents and brothers, and spend their whole lives in an unprofitable manner." [27] As a critic of conspicuous spending, Ekken was adamant when it came to the appropriate apparel for artisan and merchant women. "Her personal adornments and the color and pattern of her garments should be unobtrusive," he warned, because "it is wrong in her, by an excess of care, to obtrude herself on other people's notice." [28] Ekken's concerns were not unwarranted. As historian Cecilia Seigle has noted, the Yoshiwara courtesan exerted a formidable influence on society. It was the courtesans who set the trends for much of urban fashion and culture. [29] Ejima Kiseki (1666-1735), the author of Seken musume katagi (1717), was deeply disturbed by the townswomen who increasingly resembled the courtesans and the onnagata (female roles played by kabuki actors), and he blamed mothers who enjoyed the attention their daughters received in their frequent outings to temples and shrines. [30] The yujo-ka in this regard - the imitation of the courtesans' fashion and consumption patterns - blurred the line between the yujo and the respectable women of artisan and merchant classes. One of the most obvious symbols of yujo-ka was the adoption of the hairstyles favored by the courtesans. Author Ihara Saikaku observed in Life of an Amorous Woman that the "modern young wives have truly lost all gentleness of manner. They are forever striving to learn the [hair] styles favored by the courtesans and actors of kabuki." [31] According to historian Yasukuni Ryoichi, a man's hairstyle reflected status, but only on rare occasions when a man attended a town meeting or event, did he bother to take note of his hair. [32] By contrast, hairstyling for women was a form of self-expression. The following senryu (sarcastic poetry) mocks the seriousness with which the townswomen attended to their hair: Kami wo yufu tokiniWhen a woman does her hair onna wa me ga suwariher eyes are glued to the mirror [33] It is likely that the senryu was written when women were still able to do their own hair. But as the latest trends became more complex and difficult to imitate, the townswomen did not hesitate to seek professional help from the hairdressers. According to historian Nishioka Masako, the first female hairdressers were spotted in Osaka sometime between the Meiwa (1764-71) and Anei (1772-80) eras. While the early hairdressers catered mostly to women of the pleasure quarters, it was not long before they began attracting women of the artisan and merchant classes. Yasukuni has pointed out that popular hairstyles were not only fashionable but also convenient, particularly for the townswomen who could maintain the same set for up to one or two months. By the Kaei (1848-53) era, there were more than 1,400 female hairdressers in Edo alone. [34] The emergence of the hairdressers exemplifies how far female labor had developed by the mid-Tokugawa period. In writer Tamenaga Shunsui's Shunshoku umegoyomi (1832), one of the female characters is a young hairdresser who is described as a tomboy, otherwise known as "anego" (female boss) among the town youths. [35] While there is no reason to assume that all hairdressers took on a masculine character, it is likely that many were either self-sufficient or less dependent on the ie. Given the phrase, "kamiyui no teishu" (the hairdresser's husband) that referred to a man who lived off a woman's income, historian Seki Tamiko has suggested that the hairdressers' earnings were often on a par with men's. [36] The newly invented stereotypes that address the hairdressers' potential self-sufficiency must be considered within the context of a rapidly expanding commercial economy that supported the employment of independent wage-earning women and the society's continued fascination with yet denigration of female labor. As historian Susan Hanley has pointed out, during the course of the Tokugawa period the townspeople spent large proportions of their incomes on status goods and gifts to maintain and enhance existing social networks. [37] These acts were serious challenges to the rigid social distinctions of the period and frowned upon by the Tokugawa government. In an episode in businessman Mitsui Takafusa's (1684-1748) Chonin kokenroku (ca. 1730), a merchant of Edo is severely punished when his spendthrift wife is mistaken for a lady by none other than the Shogun himself. [38] As historian Mikiso Hane has explained, some merchant households lost their fortunes by incurring the wrath of the ruling authorities. [39] Hence the women who catered to the extravagant needs of merchant wives and daughters faced heavy consequences when they violated the official banning of hairdressers in a series of moral reforms in the late eighteenth century. Not only were the hairdressers fined, but their husbands and parents were also held accountable. Nevertheless, the hairdressers were continually brought back by popular demand. [40] At stake were not only social but also spatial demarcations. As Ekken wrote in Onna daigaku, a woman was expected to limit her trips to "temples and other like places where there is a great concourse of people" until she had reached the age of forty. [41] Historian Ono Sawako has pointed out that shrine and temple compounds were known for yuraku (play), an open space for casual contact between men and women of different classes. The hanami (cherry blossom outings), festivals, and pilgrimages were all opportunities in which men and women could join together in the games and rituals that accompanied many of these occasions. [42] In a society where existing hierarchical relations assumed distinct spatial expressions, the mingling of women of diverse backgrounds posed a particular threat to the already ambiguous boundaries of class and gender. Notwithstanding the risk of being accused of yujo-ka, the wives of merchant households continued to patronize the culture of the yujo that embraced the liberating qualities of leisure and entertainment. Seki has noted that the kabuki plays written by playwright Tsuruya Nanboku (1755-1829) were particularly popular among merchant women. One story depicts a ghost of a woman who haunts her unfaithful husband and drives him to his death. Seki has argued that the out-of-the-ordinary storylines gave the townswomen a moment to breathe in an otherwise suffocating patriarchal household economy. [43] The culture of the yujo, then, imbued a sense of liberation among women of all occupations and status, exposing the cracks in a system that bound the working women to the ie. Much like the existing social hierarchy that was honored more in the breach than in its maintenance by the eighteenth century, the respectability that Ekken's Onna daigaku attempted to restore was gradually slipping away. [44] But it was not the merchant women themselves who were to blame - they were, after all, victims of bad influence. It was, rather, the women associated with the yujo, those who had deviated from the ie system in their capacity to support themselves, who were held accountable. In reality, it was not so much the yujo as it was the growing consumer society that tempted the people of artisan and merchant classes to give in to sumptuous tastes and habits. The desire to consume both goods and services, in turn, necessitated the emergence of female occupations such as the Yoshiwara courtesans and the hairdressers. It also allowed women to engage in various types of wage work, from which the cities' numerous employment agencies profited. [45] As young women and men migrated to the city to take employment as servants and laborers, isolation and anonymity touched the ways in which people interacted with each other. In these changing and fluid communities, people were less likely to know a person's history and had to rely on external factors such as dress and hairstyle to determine a person's social standing. Yet it was precisely this ability to judge someone based on her or his appearance that was increasingly called into question. In an episode in Saikaku's Some Final Words of Advice, an employer must choose between two housemaids; one is very attractive and the other is most ordinary. When they agree to work on a trial basis, the employer discovers that the prettier of the two is incompetent while the less attractive girl could easily pass as a private secretary. The moral of the story was that one "can never tell about people just by looking at them." [46] Still, in another instance, personal appearance is rendered less dependable as it is purchased or forfeited. The protagonist in Saikaku's Life of an Amorous Woman confesses: "I now changed into a garb that fitted my new role [as chambermaid]. In every respect I made myself look like an innocent young girl." [47] It was also in this thriving economy that a variety of illegal monetary transactions emerged, including those involving the female body. Working outside the designated pleasure quarters, the women engaged in private prostitution were punishable by law. Nevertheless, private prostitution saw no signs of disappearing. For example, the suwai (kimono broker) in writer Takizawa Bakin's (1767-1848) travel narrative is described as a gentle and obedient woman, devoid of any mention of prostitution; but as historian Komori Takayoshi has indicated, it was also around this time that the suwai earned their reputations as agents of private prostitution. [48] Seen in this light, women engaged in some occupations may have provoked the image of being sexually loose by actually engaging in private prostitution. The following Edo senryu depicts the goze, or blind female street musicians who were often reduced to the life of a beggar: Goze no iro The blind woman's choice koseki no yoi otoko is the man with the sweet nari voice [49] The senryu describes the goze's flirtatious behavior in spite of her inability to see. References to affairs initiated by the goze in exchange for petty cash are common. As Yasukuni has explained, illegal prostitutes frequently disguised themselves as wandering musicians, maids, hairdressers, and waitresses. According to Yasukuni, the private prostitutes were in some ways responsible for a series of regulations concerning female house ownership in Kyoto and Osaka. It necessarily aroused suspicion when women of the above-mentioned occupations rented or owned a home. This may have caused further problems for working women particularly from the mid- to late Tokugawa period. [50] The blending of culture and the overlapping character of private prostitution and wage work, then, compounded the ascription of yujo-ka status in literary representations of female labor. However, many contradictions are inherent in the discourse of yujo-ka. On the one hand, the yujo was synonymous with female extravagance and sexual immorality. On the other hand, the courtesan was singled out for her elaborate and sophisticated tastes. It was not just the merchant wives and daughters who were mesmerized by the power of the yujo. One woman who tried to imitate a courtesan could not escape Saikaku's disgust in Seken munesanyo (1692). Everything from the way the laywoman walked, talked, and dressed did not live up to his expectations. [51] In Saikaku's Some Final Words of Advice, another woman was criticized for believing that her most important concern should be the declining fortune of her family. As she took up different forms of menial work to lift her husband's spirits, she began to pay less and less attention to her personal appearance only to look older than her age. [52] The yujo, therefore, was not a menace in itself. It was rather the fading distinction between the yujo and the laywoman in their manners and appearances that harbored potential problems. For the culture of the deviants represented the kind of freedom and independence that the townsmen were unwilling to grant all women. However, the women of artisan and merchant classes defied the codes of socially prescribed norms and pushed at the limits of respectability. As we shall see, when the state intervened in the process of delineating the two types of women and their work, the "othering" of anyone associated with the yujo became legitimized, reinforced, and eventually, normalized. The Changing Relations between Women and the State In 1832, a woman by the name of Take was arrested for stealing some old clothing from her former master's home. Take was not only accused of theft, but also—among other offenses—dressing as a man. Even the town officials were baffled by the crime and sentenced her to fifty days in prison, forbidding her from engaging in further acts of cross-dressing. Five years later, however, Take was arrested again for disguising herself as a male officer. This time, Take faced one hundred days in prison and was eventually exiled to Hachijo Island. She was only twenty-four years old at the time. [53] The unusual cruelty on the part of the town officials reflects the changing relationship between women and the state by the late Tokugawa period. As historian Seki Tamiko has noted, Take's offense entailed more than a transgression of gender. Take, a self-supporting individual with no particular affiliation with the ie, was an alarming presence in the eyes of the Tokugawa officials. [54] To be sure, with the exception of private prostitution and female hairdressing, the bakufu did little to impose legal measures regulating the activities of wage-earning women. As historian Sone Hiromi has pointed out, without a definitive system of social welfare, there was no reason for the bakufu to discourage women of lower status from making a living. [55] But as historian Natalie Zemon Davis has suggested, tales of crime and pardon could circulate among the masses not as an imposing "official culture," but as cultural exchange, conducted under an overarching authority. [56] In a climate of increasing tension between the bakufu and the prosperous merchants, talk of punishment and rewards may have functioned as a measure of social control. The state's intervention in commending those work roles that focused on the preservation of the ie became particularly salient in a time of political and economic crisis. Inspired by the already existing cultural imagery and institutionalized in the form of licensed prostitution, the difference between the yujo and respectable working women, hence the distinction between sex and reproduction, had become official. [57] In 1787, Matsudaira Sadanobu (1758-1829) became the bakufu's chief councilor to cope with the devastating consequences of a year of great floods, inflation, food shortage, and rioting. The policies he adopted were conservative in nature, and concentrated on reducing expenditures and encouraging frugality. [58] But the bakufu's endeavor to regulate and reduce the expenditure of the townspeople took unusual turns. For example, Sadanobu forbade the use of barbers and hairdressers on the premise that imitation of Kabuki actors and yujo necessarily involved excessive clothing and would, therefore, corrupt public morals. [59] As noted earlier, the ban was of little avail in imposing frugality upon the townspeople. In the hope of increasing agricultural production, Sadanobu and Mizuno Tadakuni (1793-1851), his successor in reform, encouraged the peasants in the cities to return to farming. Tadakuni further attempted to curtail secondary work such as weaving so that peasants could focus on tilling the soil. [60] In his study of artisan and merchant women in Kyoto, historian Yasukuni Ryoichi has pointed out that the specialization and diversification of labor in the textile industry created greater opportunities for female weavers within the household division of labor. [61] The demand in silk encouraged farmers to favor sericulture over other cash crops, allowing women to engage in the kinds of work that reaped higher profits than did typical male labor. Despite the growing recognition of female weavers as breadwinners in the family, the differences in the kinds of work performed led to lower pay scales for women, often at the insistence of the Tokugawa government. [62] This is not to imply that the bakufu discouraged women from working outside the home. According to historian Katakura Hisako, the number of rewards by which the machi-bugyo (town magistrate) honored the good deeds of the urban community rose particularly during the Kansei (1789-1801) and Tenpo (1830-1843) Reform eras, with forty-four cases and forty-six cases respectively. In one instance, a woman by the name of Tetsu was praised for her continuous support of her elderly father from her income as seamstress and peddler. In another example, Hisa was commended for supporting her family when her husband became permanently ill. Carrying her two-year old daughter on her back, she sold flowers in the morning, tofu and bean curd by day, and took care of her husband at night. Most of the work in this category involved street peddling, but the kind of work rewarded by the bakufu became diversified over the years. [63] Yet, the stark reality remains that women's work rewarded by the bakufu was mainly for the benefit of the family or its male members, unlike other urban occupations that stressed the individual. Behind the bakufu's ardent support for women's work, then, was a striking message that contained women to the ie system. In 1789, the bakufu arrested several thousand illegal prostitutes in Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka. In Edo, the arrested women were sent to Yoshiwara or banished to agricultural villages in nearby regions. As historian Cecilia Seigle has explained, this was an attempt to solve two problems with one measure: cleanse Edo of vice and alleviate the shortage of marriageable women in rural villages. [64] Through this gesture of punishment and discipline, the bakufu desperately sought to bolster its sense of control. In this respect, the deportation of illegal prostitutes to nearby agricultural villages resonated with the function of the ninsoku yoseba (almshouses), facilities constructed in 1790 for the purpose of providing housing and employment for the homeless and convicts of Edo. As historian Kato Takashi has illustrated, Sadanobu attempted to clear the streets of persons he considered threats to society by placing vagrants in a supervised institution. He further hoped to reform those persons to become productive members of society by introducing such potential troublemakers to the discipline and rewards of work. [65] As such, one illegal prostitute who supported a bedridden father received a lighter sentence in a private prostitution raid in 1828. [66] In this age of reform, the working woman as deviant took on a tamable character worthy of redemption, as long as she was willing to subsume her personal gains to the needs of the family. Meanwhile, the pleasure quarters became an institution where the fate of the courtesans was sealed as a necessary evil. Inherent in contemporary discourse about women's work was thus a factor that restricted both freedom and individuality. The labeling of self-reliant, outspoken women as deviants not only deprived working women of a viable identity, but also gave commoner men and the state overarching control over their bodies. As society began to rely on female labor outside the traditional household economy, the reaffirmation of gender roles became a priority. Historian Gary Leupp's analysis of the various grounds on which the bakufu rewarded the commendable behavior of commoners reveals the language that defined such gender roles: charity, loyalty, filial piety, chastity, and purity. [67] This context makes it conceivable why Take, who not only disguised herself as a man but also assumed a male identity, was severely punished for such a petty offense as theft. In a period of change and fading distinctions between established categories, evinced by the notion of the yujo-ka, ideals of gender and sexual propriety were reinscribed in other ways - lauding the women who worked to support their households but condemning those who defied male authority by working independently of the ie. Conclusion The celebration of sexuality that characterized much of Genroku culture and its representations of women in ukiyoe art and literature, then, cannot necessarily be taken at face value. With an emphasis on the female body as an object of sexual desire, Genroku culture accelerated the commodification of women through public and private prostitution. Described as young, single, and free-spirited, working women also gained visibility and recognition, but could not escape the stigma of promiscuity. Often at the hands of the ukiyoe artists and writers of contemporary literature, those women who worked beyond the confines of the ie were transformed from innocent bystanders into dangerous sexual predators. Although the pleasure quarters and the "real" yujo were accepted parts of society, the discourse of yujo-ka attempted to prevent their autonomous and transient lifestyle from spilling over to the more respectable working women of the artisan and merchant classes. Indeed the yujo exerted control over the culture of the townswomen and indirectly undermined the patriarchal household economy. Yet, the society of artisans and merchants could not afford to condemn female wage work altogether and its presence beyond the household. Carefully distinguishing between the wifely duties of married women engaged in small businesses, male writers as well as the state at once encouraged and denigrated female labor. Furthermore, in a series of reforms initiated by the Tokugawa bakufu, the discourse on deviance assumed a different character as the working woman turned aggressor now became the object of rescue. Although government crackdowns on private prostitution, both real and disguised, were customary practices, the bakufu found a novel, practical solution to this nagging problem by the end of the Tokugawa period. Rather than punishing women for their imputed association with lewd activities, the government opted to confine them to the kinds of work and areas in which their labor was most needed. In so doing, it facilitated the gradual relinquishing of a woman's right to her body and labor and foreshadowed the changing role of woman from wife and helpmeet to agent of reproduction, hence, motherhood. It would not be until the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the subsequent policies that promoted modern industry and commerce that the separate spheres ideal would take root among members of the new urban middle-class. But the continued construction of independent working women as deviant was a legacy of the "floating world." Brown University Providence, Rhode Island 1. See, for example, Okumura Masanobu, "The Traveling Woman Bookseller"; Okumura Toshinobu, "Actors as a Flower Seller and Street Musician"; and Nishimura Shigenaga, "The Actor Sanyo Kantaro as a Tea Seller" in Early Masters: Ukiyoe Prints and Paintings from 1680-1750 (New York: Japan Society Gallery, 1991). The names of those who reside or have resided primarily in Japan are written with the family name preceding the given name. 2. See, for example, Kitagawa Utamaro, "Beauties in the Kitchen" and "Needlework," in Utamaro, ed. Muneshige Narayuki and Sadao Kikuchi, trans. John Bester (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1974). 3. Mikiso Hane, Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991), 149-151. 4. Kaibara Ekken, Greater Learning for Women, trans. Basil H. Chamberlain (London: John Murray, 1905), 43. 5. Anne Walthall, "Devoted Wives/Unruly Women: Invisible Presence in the History of Japanese Social Protest," Signs (Autumn 1994): 106-36; see also Walthall, "The Life Cycle of Farm Women in Tokugawa Japan," in Recreating Japanese Women, 1600-1945, ed. Gail Lee Bernstein (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991). 6. Kathleen Uno, "Women and Changes in the Household Division of Labor," in Recreating Japanese Women; Hane, Premodern Japan, 154-5. 7. Jennifer Robertson, "The Shingaku Woman: Straight from the Heart"; Patricia Fister, "Female Bunjin: The Life of Poet-Painter Ema Saiko"; and Joyce Chapman Lebra, "Women in an All-Male Industry: The Case of Sake Brewer Tatsu'uma Kiyo," in Recreating Japanese Women. 8. Hitomi Tonomura, Anne Walthall, and Wakita Haruko, eds., Women and Class in Japanese History (Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 1999). 9. Nishioka Masako, Edo no onnabanashi (Tokyo: Kawade shobo shinsha, 1993); Seki Tamiko, Edo koki no joseitachi (Tokyo: Aki shobo, 1980). 10. I use the term essentialize to suggest that Genroku culture had a tendency to subsume all women under a common biological category regardless of their differences. 11. Yokota Fuyuhiko, "Onna daigaku saiko," in Gender no nihonshi: ge, ed. Wakita Haruko and S. B. Hanley, (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1995), 382; see also "Imagining Working Women in Early Modern Japan," in Women and Class , ed. Tamanoi Tonomura, trans. Mariko Asano. 12. Ihara Saikaku, Japanese Family Storehouse, trans. G. W. Sargent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 81. 13. Ihara, Japanese Family Storehouse, 53. 14. Ihara Saikaku, Five Women who Loved Love, trans. Wm. Theodore De Bary (Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1956), 104-5. 15. Gary P. Leupp, Servants, Shophands, and Laborers in the Cities of Tokugawa Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 50-1. 16. Ihara Saikaku, Some Final Words of Advice, trans. Peter Nosco (Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1980), 218-9. 17. Kaibara, Greater Learning for Women, 43. 18. Leupp, Servants, Shophands, and Laborers, 52. 19. Ihara Saikaku, Life of an Amorous Woman, trans. Ivan Morris (New York: New Directions, 1963), 173-83. 20. Shikitei Sanba, Ukiyoburo, trans. into modern Japanese by Nakamura Michio (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1957), 193. 21. Leupp, Servants, Shophands, and Laborers, 115. 22. Saikaku, Some Final Words of Advice, 218; see also Yokota, "Imagining Working Women,"160-3. 23. Cecilia Segawa Seigle, Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993), 9-23. 24. Sone Hiromi, "Prostitution and Public Authority in Early Modern Japan," trans. Akiko Terashima and Anne Walthall, Women and Class, 171-2. 25. Ibid. 26. Yokota, "Onna daigaku saiko," 382. 27. Kaibara, Greater Learning for Women, 35. 28. Kaibara, Greater Learning for Women, 41. 29. Seigle, Yoshiwara, 71. 30. Ejima Kiseki, Seken musume katagi, trans. into modern Japanese by Nakajima Takashi (Tokyo: Shakai shisosha, 1990), 121. 31. Ihara, Life of an Amorous Woman, 173. 32. Yasukuni Ryoichi, "Kinsei Kyoto no shomin josei," Joseishi sogo kenkyukai, ed., Nihon josei seikatsushi 3 (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990), 102. 33. Hamada Giichiro and Morikawa Akira, eds., Kansho nihon koten bungaku 31(Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten, 1977), 30. Author unknown. 34. Nishioka, Edo no onnabanashi, 38-40; Yasukuni, "Kinsei Kyoto no shomin josei," 98-102. 35. Tamenaga Shunsui, Shunshoku umegoyomi, trans. into modern Japanese by Funabashi Seiichi (Tokyo: Kawade shobo, 1974), 325-7. 36. Seki, Edo koki no joseitachi , 37. 37. Susan Hanley, "Tokugawa Society: Material Culture, Standard of Living, and Lifestyles," in The Cambridge History of Japan, v. 4: Early Modern Japan, ed. John W. Hall, et al. (New York: University of Cambridge Press, 1988), 660-705. 38. David J. Lu, "On Being a Good Merchant, 1726-33," Japan: A Documentary History (Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 229. Adapted from E. S. Crawcour, "Some Observations on Merchants: A Translation of Mitsui Takafusa's Chonin Kokenroku," Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 8 (1962), 114-22. 39. Hane, Premodern Japan, 152. 40. Nishioka, Edo no onnabanashi, 33. 41. Kaibara, Greater Learning for Women, 40. 42. Ono Sawako, Edo no hanami (Tokyo: Tsukiji shokan, 1992), 126. 43. Seki, Edo koki no joseitachi, 23. 44. By this time, the merchants who were at the bottom of the social order were financially better off than the ruling samurai elite. 45. Leupp, Servants, Shophands, and Laborers, 70. 46. Ihara, Some Final Words of Advice, 216-7. 47. Ihara, Life of an Amorous Woman, 161. 48. Yasukuni, "Kinsei Kyoto no shomin josei," 90-1; Komori Takayoshi, "Tsugi tsugi arawareru kakubaita," in Yujo, ed. Nishiyama Matsunosuke (Tokyo: Kondo shuppansha, 1985), 44. 49. Tanabe Sadanosuke, Kosenryu fuzoku jiten (Tokyo: Seiabo, 1962), 105-7. The senryu was written by an unknown author sometime between the Horeki (1751-63) and Tenmei (1781-88) eras. 50. Yasukuni, "Kinsei Kyoto no shomin josei,"74-7; see also Seigle, Yoshiwara, 210 51. Ihara Saikaku, Seken munesanyo, trans. into modern Japanese by M. Tanizawa, Z. Zinbo, and Y. Teruoka, (Tokyo: Shogakkan, 1996), 384-5. 52. Ihara, Some Final Words of Advice, 185. 53. Seki, Edo koki no joseitachi , 76-8; see also Robertson, "The Shingaku Woman," 92. 54. Ibid. 55. Sone, "Prostitution and Public Authority in Early Modern Japan," 183 56. Natalie Zemon Davis, Fiction in the Archives: Pardon Tales and their Tellers in Sixteenth Century France (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987), 112. 57. I draw upon Yokota's reinterpretation of Greater Learning for Women, "Imagining Working Women," 164-5, to understand the relationship between the sexual bodies of the prostitutes and the labor of ordinary women. 58. Hane, Premodern Japan,187. 59. George Sansom, A History of Japan, 1615-1867 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1963), 206. 60. Hane, Premodern Japan, 188. 61. Yasukuni, "Kinsei Kyoto no shomin josei," 88-97. 62. Wakita Haruko, Hayashi Reiko, and Nagahara Kazuko, eds., Nihon joseishi (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1987), 171. 63. Katakura Hisako, "Bakumatsu ishinki no toshi kazoku to joshi rodo," in Josei no Kurashi to rodo, ed. Sogo joseishi kenkyukai (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1998), 85-91. 64. Seigle, Yoshiwara, 167. 65. Kato Takashi, "Governing Edo," in Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era, eds. James L. McClain, John M. Merriman, and Ugawa Kaoru (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), 60. 66. Seki, Edo koki no joseitachi, 41-2; see, for example, Walthall, "Devoted Wives/Unruly Women." 67. Leupp, Servants, Shophands, and Laborers, 78.

0 notes

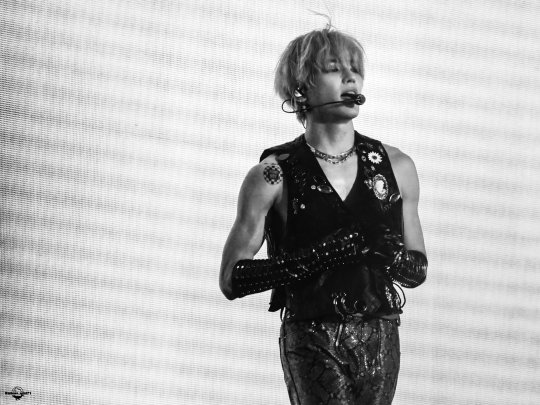

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

215 notes

·

View notes

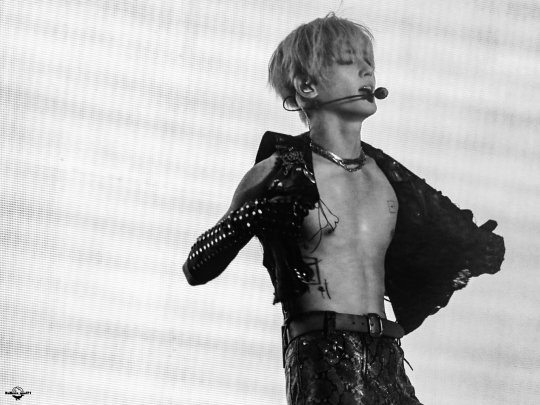

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © Ballena_azul71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © drunk for u do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © deflow do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © mixtape#71 do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © drunk for u do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220625 NCT Lee Taeyong at Neo City: Japan - The Link in Osaka Day 1 © deflow do not edit, crop, or remove the watermark

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

220625 | NCT 127 performing at the ‘NEO CITY : JAPAN – THE LINK’ in Osaka Day 1

32 notes

·

View notes