#mylatinostory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Carlos Francisco Parra

My time in the Smithsonian Latino Center’s Latino Museum Studies Program (LMSP) was one of the most significant experiences I have had in my doctoral studies. As a graduate student, a great deal of the work I must accomplish – research, reading, writing – is often done on an individual level, which can induce a state of isolation at times. Despite the archival-focused nature of most history dissertations, my study into the development of Spanish-language media in Los Angeles requires me to look beyond the limited institutional archival holdings that relate to this topic and instead engage persons involved with these media outlets as well as to look for a variety of objects that can help me piece together the story I am trying to retell.

Building upon the skills I have honed during my graduate program, the LMSP has allowed me to not only engage with the material objects and archival holdings related to Spanish-language broadcasting held at the National Museum of American History (NMAH) but to also build strong connections with distinguished historians and NMAH curators Kathleen Franz and Mireya Loza. Working with Drs. Franz and Loza I have broadened my understanding of what I am researching by exploring the different archival objects they have collected for the NMAH’s “Spanish-Language Broadcasting Collection” which covers a wide range of topics, personalities, and communities ranging from the humble origins of Spanish-language television at KCOR-TV (later KWEX-TV) in San Antonio, Texas (one of the precursors for the Univision media leviathan) to the personal recollections of Puerto Rican theater, movie, and telenovela actress Gilda Mirós. In this point in my research I have become aware of the dearth and difficulty of finding extant primary documents from Spanish-language television and radio stations from the early years of these industries. The ephemeral nature of broadcast media also complicates the ability of researchers to reconstruct historical narratives and provide analysis on these broadcasts’ contents. Through their resources at NMAH, Drs. Franz and Loza have made important strides in gathering a growing collection of oral histories and artifacts pertinent to the story of la televisión en español en los Estados Unidos.

During the summer I wrote finding aids for items within this collection, including one for Ms. Miros and another for the popular 1985 Telemundo telenovela Tainairí. Part of my responsibilities also included transcribing an oral history interview with an important figure in the early history of KMEX-TV Channel 34, the first Spanish-language TV station in Los Angeles. Working with these documents and objects is exciting because they are pieces of a greater narrative that still must be retold and studied by scholars. In the case of Gilda Miros’s career, it is exciting to historicize her trajectory as a Puerto Riqueña in telenovelas, journalism, the stage and even the big screen in her appearances in Nuyorican and Mexican films in the 1960s (the latter of which included appearances in films from the waning years of Mexican Cinema’s golden age with her role in the 1967 movie El Santo Contra la Invasión de los Marcianos (El Santo vs. The Martian Invasion). In my work with Tainairí I consulted NMAH’s growing collection on documents related to Telemundo to describe this successful 1985 telenovela produced in the network’s founding station, WKAQ-TV in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Starring Von Marie Mendez and Juan Ferrara in a series produced by Diomara Ulloa and directed by playwright Dean Zayas, Tainairí is a historical fiction telenovela which explored the struggle for abolition in late colonial Puerto Rico and examined race, gender, sexuality, and class. Tainairí is memorable as well for being one of the last great telenovelas produced by Telemundo before the rise of the network on the continental U.S. after 1987 and the ascendancy of the Miami affiliate WSCV-TV in novela production.

Beyond helping me see the larger picture of the dissertation project I am grappling with, Drs. Franz and Loza provided me with a great deal of career advice in how to enhance my scholarly career in these early stages. The enormous contribution LMSP has thus far provided to my career is also highlighted in the numerous professional relationships this experience has allowed me within NMAH and the different branches of the Smithsonian Institution. As a former high school teacher, one of my biggest motivations as a graduate student is to develop a way of linking my passion for history and learning with the larger public and leaving an educational impact on it. The public history/curatorial aspects of the LMSP curriculum has shown me some ways in which I can engage with the public at large and make scholarly work relevant. From building new professional relationships, to new friendships with other talented up-and-coming scholars, to living in such a culturally-vibrant and historically-rich city like Washington, D.C., the Latino Museum Studies Program has left an indelible mark on my long-term trajectory as a scholar and as an individual.

From left to right: Dr. Mireya Loza and Dr. Kathleen Franz of the National Museum of American History and Verónica Méndez (a fellow LMSP scholar) and myself observe a poster-size publicity advertisement in Variety magazine demonstrating the expansion of the Spanish International Network, SIN (the precursor to Univision) as of 1976. Photograph courtesy Hannah Gutierrez.

Following Dr. Kathleen Franz’s guidance on best practices for object handling, I inspect a pair of sneakers donated by Dunia Elvir, a Honduran American anchor at Telemundo 52 KVEA-TV in Los Angeles, California. Dunia’s sneakers feature a hand-drawn toucan bird, the Honduran flag, and a small Telemundo 52 logo, all crafted by one of Dunia’s fans.

A close-up of me inspecting one of the sneakers given to Telemundo 52 KVEA-TV (Los Angeles) anchor Dunia Elvir by a devoted viewer. In addition to learning about the provenance of the material objects held in NMAH’s Spanish Language Broadcast Collection, I learned about the proper method of handling these and other material objects so that they may not wear out over time and thus be available to future scholars.

Museum-level object handling practices were greatly impressed upon us during the summer 2017 Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies Program. Here I examine and handle objects from the Smithsonian’s Bracero Oral History Project along with LMSP fellows Veronica Mendez and Daniela Jimenez. In addition to learning about curatorial theory and practice, working with other emerging scholars was one of the most rewarding experiences I had during my time with the LMSP.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stay tuned as we follow Carmen Lomas Garza installing her #Ofrenda at the National Museum of American History. We will be streaming LIVE throughout the day via the #SLC_Ustream Channel #latinidadengrande #mylatinostory #dayofthedead

0 notes

Photo

Transfronteriza Chicana Nidia Melissa Bautista closes out Smithsonian Latino Center Digital Outreach inaugural broadcast series "México de Hoy" by highlighting the social and political connections between Mexico and the U.S. Watch her interview on Ustream Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum channel. #latinidadengrande #mylatinostory #Starlatino #UcscLALS #UCSC (at La Casa Azul de Frida Kahlo y Diego Rivera)

0 notes

Video

The art of Buñuelo making. Live with the Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum. #LVMCelebración #virgendeguadalupe #mylatinostory #denver @smithsonian_lvm @mizzgaby @littledreamer416 @itstetebetch

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Christina Azahar

¡Saludos a todxs! My name is Christina Azahar, a half Salvadoran/half gringa, born and raised in Georgia. I am currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Ethnomusicology at the University of California, Berkeley. Thank you for reading through my #FellowTakeover to learn more about my #LMSP2017 experience!

As an ethnomusicologist, I’m broadly interested in how music functions as a form of community-making, and how it can sustain movements toward social justice. My dissertation research, titled “Noisy Women, Imagined Spaces: Gender, Mobility, and Sound in Chile’s Popular Music Scenes,” examines how contemporary Chilean women artists like Ana Tijoux and Pascuala Ilabaca use sound as a way to navigate the physical and figurative spaces of post-dictatorship Chile. I also have also written on protest song during El Salvador’s civil war, and have a passion for teaching music in the U.S. Civil Rights era.

So, what brings me to the Latino Museum Studies Program? In 2013 I interned at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings under curator Daniel Sheehy to gain firsthand experience conducting album research and promotion. After seeing the range of ways music fit into exhibits and programs across the institution, I wanted to find a way to develop my research skills while also gaining experience in museum outreach and education. This is what led me to apply for the Latino Museum Studies Program practicum at SITES, the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service.

Christina Azahar with Practicum Lead, Maria del Carmen Cossu, outside the SITES office. Photo by Andrew Holik.

SITES functions as an exhibit ambassador for the Smithsonian outside of Washington D.C., so the office’s primary role is to travel exhibits to community centers, museums, college campuses, and other venues around the country. More than a collection of objects or banners, these traveling exhibits are meant to serve as catalysts in each community for public programming, outreach, and educational activities.

My practicum lead, Maria del Carmen Cossu, is the Project Director for Latino Initiatives at SITES. Her role involves developing exhibitions that further an understanding of the U.S. Latino experience, creating culturally sensitive community engagement and educational resources to be circulated with the exhibits, and (lucky for me!) mentoring emerging Latinx professionals in museum studies.

One of the things I’ve enjoyed most about my SITES practicum has been seeing how this office collaborates with staff and curators from across the Smithsonian. From going to off-site storage units to prepare banners for shipping, to sitting in on project proposal meetings with staff from the National Museum of American History, in my four weeks here I’ve come to understand how different Latino traveling exhibits come together from start to finish.

Christina speaking with SITES registrar Josette Cole about designing, fabricating, and shipping exhibits to venues around the country. The banners we prepped here were from the exhibition “Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program, 1942-1964,” which has been traveling for nearly ten years. Photo by Maria del Carmen Cossu.

Christina sitting in on a meeting with curator Margaret Salazar-Porcio and a team from the National Museum of American History to discuss the proposal for a potential new exhibit, “Latinos in Baseball.” Photo by Maria del Carmen Cossu.

The main SITES exhibit I’ve worked on this summer is “Dolores Huerta: Revolution in the Fields/Revolución en los Campos,” an adaptation of the exhibit “One Life: Dolores Huerta” curated by Dr. Taína Caragol at the National Portrait Gallery. One of the main goals for the summer was to develop a new traveling exhibit script and create a storyboard for interviews with Dolores to be included as an AV addition to the text and images. In the script and AV footage, we wanted to provide an intimate look at Dolores’s personal life while also celebrating her role as an organizer of the California Farmworkers movement, and contextualizing her work within the broader civil rights movements occurring in the 1960s.

There’s so much to tell about Dolores Huerta’s history and the history of the Farmworkers movement which can’t fit into a single banner exhibit, so I also worked to develop educational activities and community outreach topics which would be published as resources to complement the exhibition. One deliverable was a lesson plan on protest song and cultural revival in the Farmworkers movement in which students learn how Chicano music became a tool for organizing strikes and promoting union activity. I also proposed that SITES draw on the history of Filipino and Chicano collaboration in the movement to create outreach materials which will spark conversations acknowledging the history and potential of inter-racial solidarity and political organizing across the country.

As I wrap up my time at the Smithsonian, I realize on the one hand that I’m hugely inspired by the cutting-edge exhibitions and programming being done here to support Latinx culture and community. I mean, the Smithsonian has a “Latinx Digital Curator” position? That’s amazing! On the other hand, I’m hugely overwhelmed by the immense challenges of sharing Latinx stories with broader audiences without eliminating voices or diminishing experiences of struggle. Rather than attempt to reconcile these complex issues now though, I look forward to staying in touch with the brilliant Latinx scholars, activists, and cultural workers I’ve met here to continue imagining new ways of serving our communities, and celebrating our art in all its many forms.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Véronica Méndez

¡Hola gente! Thank you for taking the time to check out my #LMSP2017 #fellowtakeover blog post where I will share my experiences as a Latino Museum Studies Program Fellow at the National Museum of American History (NMAH).

Véronica Méndez standing in the Many Voices, One Nation exhibit in the National Museum of American History. (Photo by Rudy Mondragón) I’d like to start by introducing myself. My name is Véronica A. Méndez and I am a Ph.D. candidate and mama scholar in the Department of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I was born in México and grew up in San Antonio, Texas (Go Spurs Go!). My doctoral research lies at the intersection of Borderlands Studies, Chicana/o Studies, Latin American and U.S. History. Broadly, my dissertation interrogates how Tejanas, (women of Spanish-Mexican origin) experienced and influenced the course of empire and nation-state formation during the nineteenth century in San Antonio, Texas, across Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-Texan rule.

Dr. Mireya Loza, project lead of Documenting Spanish-Language Television, and Véronica Méndez, 2017 LMSP fellow. (Photo by Carlos Parra)

Under the direction of Dr. Mireya Loza, and in collaboration with Dr. Katherine Franz, from the Division of Work and Industry at the National Museum of American History, I am working on a project titled ¡Escuchame!: the History of Spanish Language Broadcasting in the U.S. My primary role is processing oral histories related to the development and rise of Spanish language television. The oral histories collected document the experiences of producers, reporters, chief engineers, writers, camerawomen, anchors, and set designers across six Spanish television networks: KMEX (Los Angles), KVEA (Los Angeles), SIN, WKAQ (San Juan), WNJU (New Jersey and New York), and WSCV (Miami). Together, these oral histories provide an in-depth historical perspective as new broadcasting technologies offer new and far-reaching avenues for the Latina/o communities to represent themselves and claim space within the larger fabric of the nation.

Weekly meeting at the NMAH. From left to right: Dr. Mireya Loza, Dr. Kathleen Franz, 2017 LMSP fellows Véronica Méndez and Carlos Parra. (Photo by Hannah Gutiérrez) Currently, my research focuses on the life and career of Gilda Miros, a Puerto Rican born, Nuyorican identified, author, theater and screen actress and television and radio broadcaster. Miros immigrated from Santurce, Puerto Rico to the Bronx in New York City as a small child; she later relocated to Mexico City to pursue an acting career and eventually becoming a radio and television broadcaster for SIN, WAPA, WXTV, Telemundo, WADO, JIT, and SBS. Miros’s oral history helps us understand issues of representation in media and television, along the lines of race, gender, and class, ethnicity, and nation, as well as the transnational networks that informed the development of Spanish-language broadcasting.

Handling Gilda Miros material at the National Museum of American History. These particular items document Miros travels to Vietnam as a presenter with the USO during the Vietnam War. A Puerto Rican serviceman gifted the green army hat to Miros. (Photo by Carlos Parra)

In addition to processing oral histories, I have received training in best practices for handling and processing objects acquired for the collection. These items will be utilized for an upcoming exhibit. The Smithsonian Archive Center at the National Museum of American History also houses the Spanish Language Broadcasting Collection, 1963-2015. This collection includes photographs, film stills, design plans, ratings statistics, programming, advertising, and programming for WNJU, WKAQ as well as material documenting Gilda Miros work as an actress, model, radio announcer and television talk show. Together, these objects capture significant moments in history and help frame the narrative on Spanish Language Television.

Jenarae Alaniz, Museum Specialist in the Division of Work and Industry, and Véronica Méndez looking through recently processed ¡Escuchame! objects at the National Museum of American History. (Photo by Rudy Mondragón)

Handling a large collection press badges belonging to Cuban-American journalist José Díaz-Balart. (Photo by Rudy Mondragón)

I am excited to be a 2017 Latino Museum Studies Program fellow and contribute to the ¡Escuchame! project. The history of Spanish-language media serves as a rich archive for documenting the hopes and anxieties of a growing Latina/o community, across time, as well as underscoring the rich diversity that defines it.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Ismael Illescas

Hello everyone! Thanks for making time out of your day to check out my #LMSP2017 #Fellowtakeover! In this post, I share a little bit about myself and my experience as a Latino Museum Studies Program (LMSP) fellow!

My name is Ismael Illescas and I am a doctoral student in the department of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. I was born in Ecuador but grew up in the working class neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles. I am passionately interested in identity formation and how interethnic and interracial solidarities are forged through the use of expressive cultures, particularly graffiti and street art. My doctoral research examines how the creative self-activity of working class youth who produce graffiti and street art offers us an alternative form of social belonging grounded in unconventional and democratic ways of conceptualizing and using public space in an era marked by the relentless privatization of space.

As an LMSP fellow, I have the great opportunity of working with Melissa Carrillo, the Director of New Media and Technology, at the Smithsonian Latino Center (SLC) on the practicum titled “Latinos in the 21st Century: A Digital Experience for All.” This project is an innovative and ongoing initiative that utilizes a multi-platform museum model for representing and accessing the immense amount of Latino collections and educational resources with an emphasis on digital storytelling. This digitally-centered initiative draws from existing content from the Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum, SLC public programs, exhibitions and educational products and outreach as well as Latino/a related content and materials located across Smithsonian museums. As such, it operates and is situated within a larger Smithsonian-wide digital framework.

The New Media and Technology Director, Melissa Carrillo, and Ismael Illescas in front of a canvas in homage to Don Tosti’s “Pachuco Boogie” at the Smithsonian Latino Center. Photo Courtesy of Jose Ralat-Reyes.

My participation in this practicum includes digitally curating content for the Mobile App Project as a way to expand the SLC’s presence online through testing visitor engagement in preparation for the Latino Gallery. Specifically, I engage in researching the Smithsonian collections and exhibition database while also providing support with the rapid prototyping of ideas through mini workshops. One of my main tasks includes researching the vast collections across the Smithsonian museums online in order to locate assets that pertain to Latino/a art, culture, and history that can be leveraged and included in the Mobile App.

Ismael Illescas engaging with user interaction technology at the National Museum of African American History and Culture Photo Courtesy of Diana C. Bossa Bastidas.

Participating in this practicum has provided me the opportunity to find historically significant materials on Latino/a expressive culture that advances both my academic research and contributes to the development of the Mobile App Project. One of the most exciting tasks has been digitally curating the oral histories of early Chicano/a muralists such as Willie Herrón, Frank Romero, as well as recorded discussions between Lady Pink and Lee Quiñones, both Latino/a pioneers of graffiti writing culture. These muralist and graffiti artists serve as examples that it has been Chicano/a and Latino/a artists who have been at the forefront of offering a radically different conception and uses of public space at the service of aggrieved communities.

Ismael Illescas in front of the “Petitioning With Your Feet” in the “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith” exhibition at the National Museum of American History. Photo Courtesy of Veronica Mendez.

Another important assignment was undertaking a case study that involved critically analyzing cultural competency books on Latino/a community to test the Presente framework of the forthcoming Latino Gallery. After a critical assessment of the book, I presented my findings during a roundtable discussion on digital storytelling which engaged and prompted questions from both museum and industry collaborators on how to best represent and interpret the complexity and diversity of the Latino/a in the U.S.

Ismael Illescas using the “In the Studio Producer Console” at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Photo Courtesy of Diana C. Bossa Bastidas.

As a former graffiti artist who greatly admires the wild styles produced by Los Angeles graffiti writers, locating the works of Charles “Chaz” Bojórquez, the Grandfather of Cholo graffiti, within the vast Smithsonian collections and exhibition database has been truly amazing. Having the opportunity to apply my skills, knowledge and cultural competency to projects that acknowledge the important artistic and historical contributions of Latino/a artists is both an honor and a political act. This opportunity to grow as a scholar and activist would not have been possible without the Smithsonian Latino Center.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome Latino Museum Studies Program 2017 Fellows

The 2017 Latino Museum Studies Program fellows. (Photo by Adrián Aldaba) The Latino Museum Studies Program started on July 3, 2017, welcoming a new cohort of 12 graduate students coming together for a six-week summer fellowship in Washington, D.C. The fellowship provides professional development to emerging museum professionals and scholars while looking at museum studies through a Latino lens. It provides a unique opportunity to meet and engage with Smithsonian professionals, scholars from renowned universities, and with leaders in the museum field. As with each year, each fellow will participate in a practicum project at one of the various Smithsonian Institution museums, cultural and research centers. They will share more information about their projects and interests in a series of upcoming blogs posted on this website. In the interim, let’s take a look at what each of them presented on their first day as fellows!

Christina Azahar, Ph.D. candidate in Ethnomusicology at the University of California - Berkeley, following her introductory presentation at the Smithsonian Latino Center. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Christina’s dissertation research examines gender, mobility, and spatial politics in Chilean popular music scenes, focused specifically on the music and political work of Ana Tijoux, Pascuala Ilabaca, Francisca Valenzuela, and Carolina Ozaus. She has also published work on cultural memory and protest song in El Salvador since the end of the country’s Civil War, and regularly serves as a teaching assistant for classes on African American, Asian American, and Chicano music. Born and raised in Milledgeville, Georgia, she received her B.A. at the University of Georgia in Music (saxophone) and Latin American and Caribbean Studies. After graduating in 2013, she spent the summer interning with Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, where she became interested in pursuing museum curatorial work and programming.

Christina will be working with María del Carmen Cossu, Program Director for Latino Initiatives at the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service on the practicum - Traveling Exhibition Development for Dolores Huerta: Revolution in the Fields / Revolución en los Campos.

Mayela Caro, Ph.D. candidate in Public History at the University of California, Riverside, following her presentation on Hollywoodisms: Latinx in Hollywood Films 1932-1945. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Mayela’s research field is in 20th century United States cultural history and digital humanities. She focuses on the representation of gender and Latinidad in various forms of popular culture of the 1930s and 1940s. Her Master’s thesis entitled, “Hollywoodisms: Latin American Images in Hollywood Films, 1933-1945,” analyzes the manner in which Hollywood represented Latinx actors and how the images that conveyed Latinidad shifted with the implementation of the Censorship Code and the onset of WWII. Her passion for Latino Studies derived from a young age.

Mayela will be working with Taína Caragol and Leslie Ureña, Museum Curators at the National Portrait Gallery, on the practicum -“Piecing Together” Latinx Art and History in the 19th Century.

Shakti Castro, a May 2017 graduate of the Public History Masters program at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, following her presentation titled “Do Puerto Ricans Speak Puerto Rican? Boricuas in the Barrios and Beyond”. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas) Shakti Castro is a Puerto Rican Diaspora historian born and raised in The Bronx. She received a B.A. in media studies and English literature from Hunter College at CUNY, where she spent four years at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies as a research assistant and oral historian. During her time at the Center, she was a research assistant who helped launch the Center's latest oral history initiative, Centro Memorias. As part of Memorias, Shakti conducted over 30 oral history interviews with artists, educators, and leaders within the community. This May, she received an M.A. in History with a graduate certificate in Public History, from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. During her time at UMass she worked with the university's new Oral History Lab assisting with workshops and hosting listening parties.

Shakti will be working with Katherine Ott, Museum Curator at the National Museum of American History on the practicum - Health Modalities and History in Latinx Communities.

Jonathan Cortez, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of American Studies at Brown University, following their introductory presentation at the Smithsonian Latino Center. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas) Jonathan Cortez is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of American Studies at Brown University. Jonathan received their B.A. in Mexican American and Latina/o Studies and Sociology from The University of Texas at Austin in 2015. They received their M.A. in Public Humanities from the John Nicolas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage in route to their Ph.D. Their work focuses on Latinx history, 20th-century agricultural labor, comparative/relational ethnic studies, and public humanities. Specifically, Jonathan focuses on the construction of locally- and federally-funded labor camps and the lived experiences of laborers in these camps through issues of race, gender, health, and immigration.

Jonathan will be working with María Martínez, Program Specialist; and Antonio Curet, Curator at the National Museum of the American Indian on the practicum - Contextualizing Museum Archaeological Collections: The Case of Pre-Columbian Mirrors.

Maeve Coudrelle, Ph.D. candidate in the Art History Department at Temple University, following her introductory presentation at the Smithsonian Latino Center. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Maeve Coudrelle is a Ph.D. candidate and University Fellow in the Art History Department at Temple University. Her dissertation focuses on biennials, print culture, and theories of cultural contact, looking specifically to global print exhibitions from 1950 to the present in Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States. Focusing on regions with colonial pasts and a connection to the print as protest, her dissertation will highlight the role of exhibitions in positioning the identity of a city or nation on the global stage. She hopes to make clear not only the potential of visual objects to re-orient our understanding of human interaction and encounter, but also to underscore that exhibitions exist as theoretical arguments, rather than unbiased histories. Maeve will be working with Michelle Joan Wilkinson, Museum Curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, on the practicum - Research of Black and Latino designers.

Stephanie Huezo, Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University, Bloomington where she is studying Latin American and Latino History, following her presentation on “Maestros populares and the Narrative of Liberation in El Salvador and in the U.S. – Salvadoran Diaspora (1980 – 2009)”. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas) Stephanie Huezo is a Salvadoran-American and New York native. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University, Bloomington studying Latin American and Latino History. Her dissertation focuses on the community-based education in El Salvador, critically examined everyday experiences of students to raise consciousness of the oppressed. She analyzes how teachers used popular education as a tool for resistance, as a strategy for survival during the civil war (1980-1992), and its impact on the U.S. Salvadoran diaspora. Stephanie will be working with Ranald Woodaman, Director of Exhibits and Public Programs (and LMSP Alumnus), at the Smithsonian Latino Center on the practicum - Latino DC History Project: Interpreting Central American Women’s Work.

Ismael Illescas, Ph.D. candidate in the Latin American and Latino Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, following his presentation on “Born to Create: Graffiti, Street, Art, and Patial Politics in the Post Industrial City of Los Angeles”. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Ismael Illescas is a Ph.D. candidate in the Latin American and Latino Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His interest in graffiti and street art stems from his involvement in the subculture growing up in South Central Los Angeles during the early 2000s. His research registers Latin@s contributions to the making of graffiti and street art in Los Angeles, and examines the contradictions concerning its celebration in museum and gallery spaces and its criminalization outside of those spatial confines. He has a B.A. in Sociology from the University of California, Santa Barbara as well as an Associates of Arts degree in Liberal Arts from Santa Monica College.

Ismael will be working with Melissa Carrillo, Director of New Media & Technology (and LMSP alumna) at the Smithsonian Latino Center on the practicum - Latinos in the 21st Century: A Digital Experience for All.

Daniela Jiménez, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Chicanx Studies and a first-year student in the MLIS program at UCLA, following her presentation on Exploring Relational Chicanxs Studies/U.S. Latinx through Popular Culture and Japanese Cultural Productions. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Daniela Jiménez is a third-year Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Chicanx Studies and a first-year student in the MLIS program at UCLA. Most recently, she is completing a graduate certificate program through the Urban Humanities Initiative --an interdisciplinary effort to explore urban space and cities as artifacts through the fields of architecture and design, urban planning, and the humanities. Her research interests include the reconfiguration and reinterpretation of Chicanx and U.S. Latinx in European and Asian countries, the role of social media in intercultural exchange, community-based archives, and archival theory and practice. Outside of her graduate work, Daniela is involved with the revitalization of Third Woman Press. Daniela will be working with Alison Oswald, Archivist at the National Museum of American History, on the practicum - Documenting Spanish Language Television through Archives.

Verónica Méndez, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, following her presentation on Locating Tejanas in Nineteenth Century U.S. – Mexico Borderlands. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Verónica Méndez was born in Mexico, and raised in San Antonio, TX. She completed her graduate training in the Midwest and is currently living in New Haven, CT. She is a first-generation immigrant, mama scholar and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Working at the intersection of Borderlands Studies, Chicana/o Studies, Latin American and U.S. History, her dissertation interrogates questions of sovereignty, race, gender and citizenship across shifting regimes in nineteenth century San Antonio, Texas. Her focus centers on how Tejanas experienced and negotiated their in/exclusion from imperial and national constructions of citizenship and subject making.

Verónica will be working with Mireya Loza, Curator (and LMSP alumna) at the National Museum of American History on the practicum - Documenting and Collecting Spanish-language Television.

Rudy Mondragón, Ph.D. candidate in Chicana and Chicano Studies at the UCLA, following his presentation on “That’s Totally Disrupting”: Ring Entrances as Sites of Resistance. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Rudy Mondragón is a Ph.D. candidate in Chicana and Chicano Studies at the UCLA. His research intentionally responds to Jorge Iber and José Alamillo’s call upon scholars to examine the racialized, gendered, class-based and transnational dimensions of sport among Mexican American and Latina/o experiences. Rudy’s research utilizes the sport of boxing as a site to interrogate representations of race and ethnicity, masculinities, immigration, and citizenship. His focus is on the ways boxers of color use spatial strategies to negotiate their position within and beyond the neo-liberal structures of boxing to creatively claim space, perform resistance, and disrupt the status quo. Methodologically, Rudy is interested in textual analysis of media, archival work, participation observation, and in-depth interviews. Rudy will be working with Margaret Salazar-Porzio, Curator at the National Museum of American History on the practicum - Latinos and Baseball: In the Barrios and the Big Leagues.

Pau Nava, Ph.D. candidate at the University of Michigan’s American Culture program, following their introductory presentation at the Smithsonian Latino Center. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas)

Pau Nava is a self-identified Art Queerstorian. Pau’s research centers on visual representations of queer Latinidad. As a genderqueer person of color, Pau’s social location is a driving force for their consideration of gender within transgender studies that interrogates the limits of the gender binary. They received their B.A. in Art History and Latinx studies, and as a native of the Chicagoland area, spent their undergraduate career researching mural history in Chicago’s Mexican-American neighborhood of Pilsen through the McNair Scholars program.

Pau will be working with Josh Franco, Collection Specialist at the Archives of American Art on the practicum - Research & development of Collection Plan for a target area of the United States.

Carlos Parra, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Southern California American Culture program, following their introductory presentation at the Smithsonian Latino Center. (Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas) Carlos Francisco Parra is a doctoral student in the University of Southern California’s Department of History. Inspired by his experiences growing up in a bicultural border town, Parra is fascinated by the issue of cultural identity formation among Mexican Americans in the greater U.S.-Mexican border region. His research focuses on the cultural, political, and economic development of that international boundary as well as the formation of identities and communities along the border. Prior to his doctoral work, he attended the University of Arizona (B.A. in Secondary Education) and the University of New Mexico (M.A. in History) and also served as a public high school history teacher in his home community in Nogales, Arizona. Carlos will be working with Kathy Franz, Curator at the National Museum of American History on the practicum - Documenting and Collecting Spanish-language Television.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Rudy Mondragón

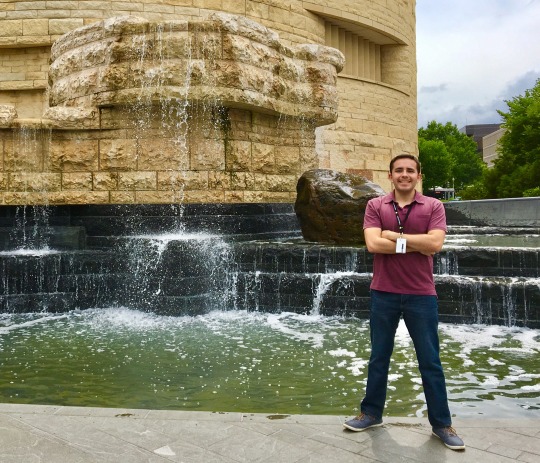

Rudy Mondragón standing outside of the National Museum of American History. Photo Credit: Veronica Mendez

What’s up y’all! First and foremost, I would like to thank you for taking the time to check out my #LMSP2017 #fellowtakeover blog piece where I will share a little bit about myself and my experiences with the 2017 Latino Museum Studies Program (LMSP).

My name is Rudy Mondragón and I am a Ph.D. student in the Chicana and Chicano Studies Department at the University of California, Los Angeles. I grew up in South Gate, a city located in South East Los Angeles. In the early 1990s, my father introduced me to the sports of baseball, boxing, and soccer. As a result, I developed an interest in soccer and eventually earned a scholarship to play division-1 soccer for the University of California, Irvine. Though I participated in soccer, I developed a passion for boxing that started off as a hobby and is now the subject of my life’s work. My doctoral research utilizes the sport of boxing as a site to interrogate the ways in which boxers perform race, masculinity, and citizenship as well as how boxers perform subtle forms of resistance through the politics of fashion and soundscapes while situated in their specific socio-political and historical contexts.

Rudy Mondragón and Dr. Margaret Salazar-Porzio working inside a National Museum of American History processing room. Photo Credit: Luke Perez

As part of the LMSP practicum component, I am supporting Dr. Margaret Salazar-Porzio on the Latinos and Baseball: In the Barrios and the Big Leagues project. This multi-year community collecting initiative is situated in the National Museum of American History (NMAH) within the Division of Home and Community Life and is in collaboration with the Smithsonian Latino Center. This collecting initiative focuses on the historical role that baseball has played as a social and cultural force within Latina/o communities to explore how racial, ethnic, gender, national, and cultural identities are forged within an increasingly globalized world. By using baseball as a site of analysis, this project builds on original research, oral histories, and collections by and with partners that are found all over the country.

Rudy Mondragón and his practicum lead, Dr. Margaret Salazar-Porzio, collectively viewing an object from the Latinos and Baseball project. Photo Credit: Luke Perez

My role with this project is to focus on the baseball objects collected from our partners at the Kansas City Museum. Some of these objects include baseball uniforms from the Aztecas and Eagles teams from Latino baseball leagues, a pair of baseball cleats, helmet, baseball bat, catcher’s mitt, and a beautiful Aztecas letterman jacket from the 1960s. I have been tasked with writing descriptions and documenting the condition of each object. In addition, I have conducted phone interviews with the donors of these artifacts to gain more contextual information. The stories that the donors share help bring each object to life and provides us with an opportunity to explore the historical significance that baseball has played for Latinos in forging communities despite the forces of racism, segregation, and discrimination that are at play.

Jack Johnson collectible cards that were included in early cigarette packages. This card was part of a 1910 series included in Hassan Cigarettes

As a Chicano Sports Scholar, working at the NMAH has proved to be a valuable resource for me. I have had multiple opportunities to meet sports curators who are doing important work in sharing critical stories through a material culture approach. Recently, I had the chance to browse the sports collections at NMAH with Eric W. Jentsch, the Deputy Chair and Curator of the Division of Culture and the Arts who specializes in the history of sports and pop culture. During our hour long meeting, I viewed Roberto Clemente’s Pittsburgh Pirates jersey, a baseball signed by Jackie Robinson, and Hank Aaron’s Milwaukee Brewers number 44 jersey. Outside of baseball, I viewed collectible cards of boxing great Jack Johnson that were included in early 20th century cigarette packages, a Muhammad Ali robe, Joe Louis gloves, and an Irish-American Boxing Trophy Belt made in the 19th century. I left this meeting wanting to know more stories about each of the objects I viewed. This reflection reminded me that the vision of collecting sporting artifacts and unveiling the multiple stories that accompany them is an ongoing project that will require collaborations, innovation, and creativity.

Eric W. Jentsch (left) and Rudy Mondragón (right) holding Irish-American Boxing Trophy Belt, 1850-1900.

Being a part of the Latinos and Baseball: In the Barrios and the Big Leagues project and working with Dr. Margaret Salazar-Porzio and her team has been an enriching experience. I feel empowered to take the skills I have learned here and put them to practice with my own research to better serve my communities. I am thankful for being a part of the LMSP because the Smithsonian Latino Center staff has created a space where scholars, intellectuals, and practitioners can come together to discuss the ways in which Latina/o and Latinx communities can be represented inside of museums in socially just and humanized ways.

You can follow me on social media at the following handles: Twitter: @boxingintellect Instagram: boxingintellect

Additional Photos

Muhammad Ali (1942-2016) "The Greatest" gained fame for his boxing skills, charisma and the controversy he generated outside the ring. In 1976 the Smithsonian acquired Ali's boxing gloves and robe for an exhibition on the American Bicentennial, A Nation of Nations. Photo Credit: Rudy Mondragón

The American Stories exhibit features “A Segregated Game,” objects that tell a story about race and the exclusion of Black players from major league baseball. The Negro Leagues offered Black players an alternative space to play ball. Photo Credit: Rudy Mondragón.

The Latino Museum Studies Program fellows had a special behind the scenes tour of the Museum’s offsite facility as part of the program schedule. This photo finds Rudy Mondragón standing in front of the Lowrider ‘Dave’s Dream’, an object not currently on view. This 1969 Ford LTD is an example of Latina/os forging community through the cultural art form of low riding. Photo Credit: Diana C. Bossa Bastidas

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Stephanie Huezo

Stephanie Huezo at the Smithsonian Latino Center. Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas

Hola todxs! I’m Stephanie Huezo, PhD candidate in History with a minor in Latino Studies at Indiana University-Bloomington. I’m excited that you are joining me in my #LMSP2017 #FellowTakeover post!

I research Salvadorans in both El Salvador and the United States. My dissertation focuses on the emergence of popular education in El Salvador, a community-based education that critically examines everyday experiences to raise consciousness of the oppressed. Specifically, I analyze how community organizers used popular education as a tool for resistance and a strategy for survival against hegemonic powers during the civil war and neoliberal democracy in El Salvador. My work examines community organizers beyond the nation state to demonstrate how popular education, as a practice of resistance, transfers and reconstitutes itself in the diaspora, serving as a strategy to navigate racial, class, and economic tensions through community organizing. It is within these spaces where Salvadorans create new forms of identities and meanings of belonging while keeping preexisting moral ethos that equipped many during the civil war.

I was drawn to the Smithsonian’s Latino Museum Studies Program because of its commitment to increasing the representation, research, and knowledge of Latino history. As a program fellow, I am working with the Smithsonian Latino Center’s Exhibitions and Public Programs Director, Ranald Woodaman, on the Latino DC History Project. This important multi-year project focuses on showcasing the presence and contributions of the Latinx community in the D.C. metropolitan area. I have the privilege of conducting oral histories with Central American Women for this year’s theme on Central American Women’s Work. As a transnational scholar who spends most of my time interviewing people in El Salvador, I came prepared for the job. However, conducting interviews with working women of different social classes in a busy city was not the same as my experience in a small town in El Salvador. I had to adjust to a new setting and new group. Thanks to the LMSP workshops and experiences of Smithsonian staff, I quickly adapted to my new environment and went on to conduct nine oral histories!

I conducted an interview with Jackie Reyes, the first Salvadoran to hold the position of Director of the Office of Latino Affairs for the government of the District of Columbia. We talked about her experience immigrating to D.C., her involvement in the Latin American Youth Center, and her work with the D.C. Latinx community. Photo by the DC Mayor’s Office of Latino Affairs.

Ranald Woodaman and I in front of the iconic Celia Cruz at the Smithsonian Latino Center offices. Photo by Diana C. Bossa Bastidas

My practicum has also prompted me to visit many places in the District, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) area and participate in local events to recruit potential interviewees. I attended an event for Latino Conservation Week hosted by the National Parks Service, visited the Latin American Youth Center, attended a workshop for day laborers, met with scholars from the University of Maryland, and visited the Salvadoran Consulate for an exhibition on the effects of the Salvadoran civil war in the diaspora. These visits helped me understand the intersection of belonging and space. What was once a Latinx barrio (the Columbia Heights, Mt. Pleasant, and Adams Morgan neighborhoods) is now a gentrified space. Many Latinxs have moved to the suburbs in the last two decades because of the high cost of living. My work with the Smithsonian was even affected because that meant I had to travel longer distances to conduct interviewees. However, many of my interviewees still expressed an attachment to these neighborhoods and some even still consider these spaces home even if their literal home is in the suburbs of Maryland. It was in these areas that the Latinx community felt, what Dr. Ana Patricia Rodriguez calls, Wachintonians.

I attended the “Making a New Home: The Founding of Latino D.C.” tour co-sponsored by the National Parks Service and the Latin American Youth Center. By the end of the tour, I ended up helping and translating the tour for the many Spanish speaking attendees. Photo by Mayela Caro.

The Latino Museum Studies Program has provided me the opportunity to grow as a scholar and an activist. Even though I am not a D.C. resident, I encouraged myself to participate in as many activities with the local Latino community to learn about them and their experiences in the nation’s capital. It’s important for me to represent a varied and nuanced history of Central American women in D.C. and their contributions to the workforce in my research and I believe the only way that is to be done is by understanding the Latino community’s everyday lived experience. Working with the Smithsonian has strengthened my commitment to community-based research where I, as a scholar, will also work and give back to the community I study. With the LMSP fellowship, I have contributed, even if in a small way, to bringing the stories of the Latinx community to life but more importantly, as a Salvadoreña, I have been inspired by the Salvadoran community in D.C. to continue the work I’m doing both in academia and in my own community.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Pau Nava

As a good luck charm, I brought a small Polaroid from the first time I met Chicanx art critic Tomas Ybarra-Frausto. The Archives of American Art (AAA) is home to the papers of Dr. Tomas Ybarra-Fruasto, which document Chicanx and Mexican Art in the United States. ¡Hola todx!

My name is Pau Nava and I am a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan’s Department of American Culture. Within American Culture, I frame myself as a self-proclaimed “Art Queerstorian” invested in documenting the public art of Midwestern Mexicanidad and queer Latinidad. As a scholar, much of my research has centered on the muralist movement of Mexican Chicago, Chicanx art and transgender studies.

The first time I met Tomas Ybarra-Frausto was at Chicago’s 2016 Latino Art Now! Conference. Coincidentally, this is the same conference where Dr. Josh Franco sat down with Marc Zimmerman and Len Dominguez and acquired the AAA’s first ever digital born collection that I am working on as part of my practicum this summer. The Polaroid photograph and courage to approach Dr. Ybarra-Frausto was provided by Chicago artist Gabriela Ibarra.

This summer, my LMSP practicum is at the Archives of American Art (AAA) under the mentorship of Latinx collections specialist, Dr. Josh Franco. My practicum involves me helping process a newly acquired digital born set of interviews of Chicago Latinx artist from the 70s to early 2000s. The collection is so newly acquired it does not have an official name yet. Since the Archive’s inception, this is the first time a collection is acquired completely digitally.

This photo shows my practicum lead, Dr. Josh Franco, and I, discussing my findings.

Contrary to what people may imagine when they think of archives (boxes and physical folders), my archive experience has been spent listening to different audio files and browsing online images. Part of my practicum duties include helping to process and aid the Archives with identifying the collection strengths so that they may be useful and accessible to future researchers.

I use the landmark Chicanx art exhibition CARA: Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985 for fact checking. Despite it never having been hosted in Chicago, it’s existence is still very much a part of the conversations in the artist interviews I am working with.

Chicago holds a special place in my heart as a first-generation art historian. I grew up in the suburb of Elgin, IL., about 45 minutes from Chicago. I remember the train rides where my mother would take my brother and I to the different free museum days within the city. Before starting grad school I moved to Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood where a lot of the art spaces mentioned in my #LMSP2017 project take place. As a predominantly Mexican American neighborhood, Pilsen’s many murals captivated me because it was the first time I saw my Mexican culture unapologetically grace public spaces.

The Pilsen community greatly felt the loss of Maestro Guerrero who passed away in 2015.

My first mural tour was led by Pilsen’s esteemed artist and educator Jose Guerrero (1938-2015) as part of DePaul University’s first ever art history course on Chicanx art. When we hear about Chicanx art and Mexican visualities we tend to turn to places like the west coast and greater southwest. From my work in the Pilsen community and suburban Mexicanidad, my mission is to open the door for more representation of the Chicanx and Mexican art in the Midwest. Many of the artist interviews I am listening to this summer were created as part of a cd project honoring the legacy of Maestro Guerrero and artist Jose Gamaliel Gonzalez. There is something really powerful about helping contribute to a history so close to home. Although Pilsen is present in the Archives of American Art, it does not mean its history is done being documented. I leave with more questions regarding erased local landmarks such as Casa Aztlan and the voices of muralists such as Juanita Jaramillo, whose name haunts Pilsen mural history as one of the few women mentioned in Chicago’s early Latinx murals.

Picture of a 1987 art exhibition catalog of Pilsen’s Mexican Fine Arts Center (now known as the National Museum of Mexican Art) where a lot of Pilsen’s early muralists were exhibited. Many of their artistic careers and practice as artists fostered by the existence and art networks of organizations such as Casa Aztlan.

Through my work within the art history of Pilsen, displacement and gentrification are an ever-present violence in the community. Casa Aztlan is most easily recognized for its place as the cover to a book that highlights women activists involved this cultural organization titled Chicanas of 18th street. As I listen to the stories of artists such as Marcos Raya, Ray Patlan, and Dulce Pulino, I recognize the lack of recognition Casa Aztlan has towards its many contributions to the artistic training of some of Pilsen’s earliest Latinx artists. As I complete my time at the Archives of American Art, these findings make me question if this is a dissertation topic that has fallen on my lap.

As LMSP2017 comes to its final weeks, I find myself with more questions in my researcher toolkit. As a city that has terrible weather conditions for murals, taking pictures and interviewing artists is a valuable part of art historical work within the city of Chicago. I am getting ready to return to the Midwest with the hopes that my findings help spark more celebration and dialogue about the rich Latinx art history of Chicago.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Maeve Coudrelle

Maeve Coudrelle in front of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Hello all! I’m excited to be sharing this post with you about my #LMSP2017 practicum project. Thanks for taking the time to read my #FellowTakeover!

My name is Maeve Coudrelle and I’m an Art History Ph.D. student at the Tyler School of Art, Temple University in Philadelphia. My research focuses on graphic art in the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean, looking to the intersection of activism, biennial exhibitions, and regional identity. I study how exhibitions can shape our understanding of migration and cultural contact – specifically through the lens of printmaking.

I was immediately drawn to LMSP’s focus on critically examining how institutions can work with the public to productively question categories like “American,” “Latino,” or “immigrant.” Museums, as significant repositories of historical and cultural information, are spaces where exchange and informed debate can become focal points.

Maeve Coudrelle with Michelle Joan Wilkinson at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, overlooking the National Mall. My practicum, working with Curator Dr. Michelle Joan Wilkinson at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), has allowed me to directly contribute to the expansion of a collection that explores American history in all its complexities. I am continually inspired by NMAAHC’s commitment to fostering informed and thoughtful conversation, acknowledging a long diasporic history of trauma and violence, while also centering moments of resilience, triumph, innovation, and celebration. At NMAAHC, my primary responsibility is to conduct research to assemble a select list of African American and Latinx designers to inform potential acquisitions. It’s exciting to be able to explore the work of graphic, product, and architectural designers, knowing that one day these figures might be represented in the NMAAHC collections.

Bed frame designed by Henry Boyd, ca. 1840, displayed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. My first project when I arrived at the museum was to assemble a list of the current design-related objects on view in the galleries. These objects range widely, from metal jewelry by Art Smith to intricate hats by Mae Reeves to a bedstead by Henry Boyd, all innovative and beautiful objects that demonstrate artistry, business acumen, and invention. A noteworthy aspect of the NMAAHC galleries is that objects aren’t separated by medium or type. Instead, they are incorporated into a larger historical narrative, used to illustrate important stories and moments in time. As such, there is no “design” section; as in our daily lives, design is everywhere, shaping space in ways that may go unnoticed.

Maeve Coudrelle and Michelle Joan Wilkinson, discussing digital resources on the NMAAHC website.

My typical workday at NMAAHC consists of visiting Smithsonian libraries, including the NMAAHC and American Art and Portrait Gallery Libraries; locating and reading relevant resources; and compiling key information on designers of note. The final outcome of my practicum entails assembling a digital storyboard spotlighting select designers.

Working at NMAAHC has given me the chance to experience how art-related research and collecting can be combined with a focus on inclusive and responsible museum practices. It’s inspiring to see objects that I teach and study, including prints by Emory Douglas and Wadsworth Jarrell, incorporated into a larger story that centers crucial conversations. I look forward to learning more about how exhibitions can trouble exclusionary narratives and explore the ever-changing permutations of identity, migration, and cultural exchange that animate our lives.

All photographs by José Ralat-Reyes.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Shakti Castro

Hi Everyone,

I’m Shakti Castro, a recent graduate of the University of Massachusetts Amherst public history master’s program, and my work focuses both on how the Puerto Rican Diaspora has helped shape American cities and how these cities have shaped Puerto Rican communities. Using oral history as my primary methodology, I examine community and identity formation, cultural production, and, more recently, issues around public health.

My summer practicum, a part of the Latino Museum Studies Program, is titled “Health and History in Latinx communities.” Under the supervision of Dr. Katherine Ott, of the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, I am determining best practices in documenting the histories of substance abuse and harm reduction outreach in Puerto Rican communities in New York City. This project will result in a collection plan to assist the museum in identifying objects and documents around this seldom studied history that should be added to the collections.

Looking through harm reduction items in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Division of Medicine and Science collections.

Harm reduction programs, I am learning, assist those who deal with drug addiction, and they often include, but are not limited to, needle exchange programs, campaigns for safe injection sites, and free “rescue kits” including the life-saving medicine Naloxone for opioid overdoses. Within the museum’s harm reduction-related items are needle exchange kits with clean hypodermic needles, alcohol swabs, and bottles of chlorine. There are also brochures, flyers, and zines. Looking through these items, I was most struck by the empowering language used in the printed materials, respecting the agency of those who used heroin and other drugs. The zines and brochures emphasize that what a person puts in their body is their right and choice, and the kits are about enabling people to make the safest choices they can, even with addiction. Harm reduction is about empowering people who often feel they have no choice so that, eventually, if and when they are able, they can take the first step on a long journey towards recovery if they so choose.

This bottle, labeled in both English and Spanish, is meant to sterilize hypodermic needles and cut down on the transmission of HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C, and other blood borne illness among IV drug users.

Some of the harm reduction-related items in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Division of Medicine and Science collections include art created by those who have dealt with addiction. This piece includes paint, photography, and poetry.

In working to document how opioid addiction has affected the Puerto Rican community, many ethical and practical questions arise. How do we best represent this history materially? How do we choose objects that allow us to tell stories that are compassionate and don't compromise the dignity of the people involved? In curating a collection, for research or for an exhibit, my priority is to find items that illuminate the ways in which Puerto Ricans have been active agents in healing their own communities, through the creation of harm reduction and rehabilitation programs, as well as other kinds of organizations.

Though this is a difficult and painful part of the Puerto Rican experience in the U.S., it’s an important one that should be documented. It is one piece in a much larger story around migration, urban change, and resilience. What’s important to me is to represent this history with compassion, as well as acknowledging and respecting the dignity and agency of those affected by addiction. I am grateful to be doing this work as a Smithsonian Latino Center fellow, helping to document Latinx history in all its complexity.

All photographs by Sarah Goldberg, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History Intern.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Jonathan Cortez

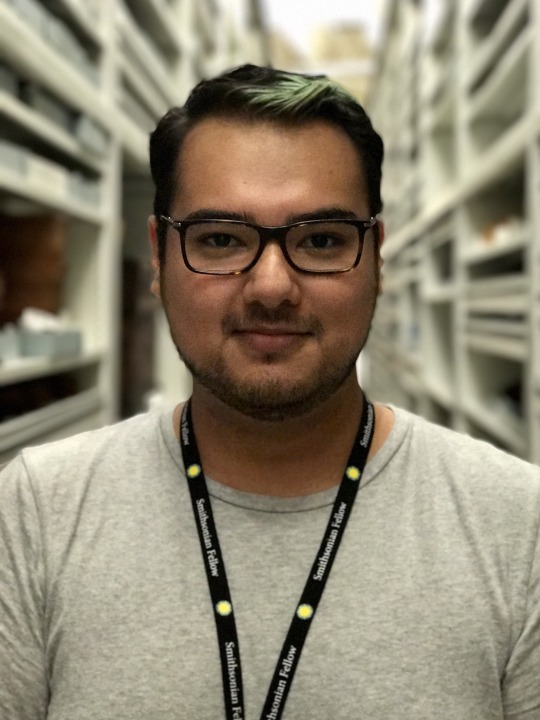

Jonathan Cortez at the Cultural Resources Center branch of the National Museum of the American Indian.

¡Hola todxs!

My name is Jonathan Cortez and I am currently a doctoral student in the department of American Studies at Brown University. Thank you for joining me on my #LMSP2017 #FellowTakover blog post. Be sure to check out my #DayInTheLife by following @Smithsonian_lmsp on Instagram.

Growing up in the coastal bend region of South Texas in the town of Robstown, it is from this region’s history and proximity to the U.S.-Mexico border where I draw my inspiration for academic research and community involvement. My work focuses on the role of federally-funded labor camps along the U.S.-Mexico borderlands as a site for specific formations of race, gender, and human control during the early-to-mid twentieth century. In addition to my academic work, I find museums to be an important space to disseminate and co-create histories with communities often left out of museum narratives. Being a Latino Museum Studies Program Fellow has allowed me to hone both my research skills and my interest in museums with a focus on having a responsibility to communities.

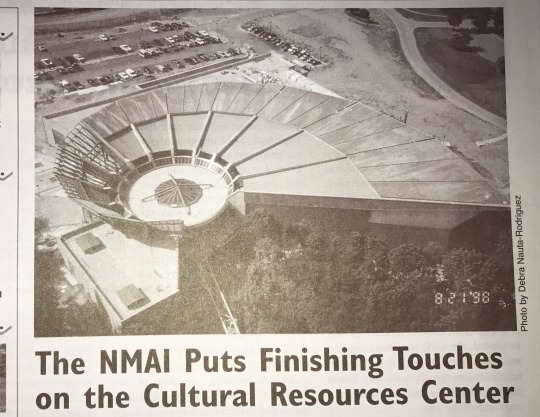

Top view of Cultural Resource Center. Photo by: Debrah Nauta-Rodriguez, from Runner No. 98-5, Sept/Oct 1998.

My practicum project is at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Cultural Resources Center (NMAI-CRC) where I am supporting Dr. Maria Martínez and Dr. Antonio Curet with the “Contextualizing Museum Archaeological Collections: The Case of Pre-Columbian Mirrors” project. Fun fact: the CRC holds most of the museum’s collections, about 98%. The NMAI views their collections as “living” in the sense that ancestral spirits continue to travel with these objects. This informs where the objects are kept, the proximity to other each other, what direction objects face, and how they are handled. By acknowledging the often violent ways in which these collections were acquired, the NMAI vows to stay in communication with Native communities and invite communities into the space to visit with their ancestral objects, and, if requested, take steps towards repatriation.

Jonathan Cortez examining the obsidian “mirror.” Photo by Maria Martínez.

My time since being at my practicum site has been a crash course in all things museums studies. Meetings about library research, archival material, data analysis, and cataloging are only a few of the training I have gone through. Curation, design, and collections will come in the next few weeks. The more special moments of the practicum thus far have been being on tours, especially with Native communities. The histories of these objects come face-to-face with their living descendants and are accompanied by many mixed emotions.

Tours with Native communities gives meaning to the collections beyond research purposes. On one tour with the Southern Ute from Colorado, the spiritual leader led a prayer in both Numic (Uto-Aztecan) and English. The CRC staff was encouraged to join the circle. The spiritual leader then prayed for the objects, acknowledging the looting and violence that took place for the museum to acquire, and he prayed for the staff, to be sure we can take care of the collection but also so that no spirits linger with us after we leave. The Southern Ute tribe proceeded to the private ceremonial room for more private prayer and smudging, if requested. As the tour journeyed through the collections, gasps at the astonishment of the objects could be heard alongside sniffles coming from a few tearful tribe members. These tours continue to bring with them emotional responses, evoking histories untold and peoples dispossessed.

Personally, this practicum continues to force me to reflect on the role of indigeneity in Latinx Studies. Traditionally indigeneity has been discussed, and rightly critiqued, within the scope of Chicanidad and the notion of mestizaje. However, working with the NMAI and getting to visit with Native communities moves past this historiographical view. Native communities are still here and continue to contribute to Latinidad as well as building their own identity within and beyond the U.S. nation-state. My time at the NMAI and CRC will continue to push me to center communities in the creation of museum design, content, and collection.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes

Text

Arepas, Pupusas, and Bocoles: Colombia, Venezuela, Central America, Mexico, and the U.S.

by Xánath Caraza

Round food is present in many cultures of the world. Round cakes, round bread, round corn cakes, round, round, round food. In Latin America, maize is one of the main sources of food. It is deeply rooted in Meso-America, a cultural region from approximately Central Mexico to Panama. Meso-America, in order to be culturally defined as Meso-America, shares similar cultural patterns, for example, the use of codexes, the identification of Quetzalcoatl (the plumed serpent god in its different manifestations) and the cultivation of maize among other similarities. However, beyond Panama, in other countries such as Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Chile, corn is also part of traditional diets. Often a wide variety of corn is available including sizes of kernels, colors, and tastes. What I have noticed is that there is a round pattern of food made out of corn throughout the Americas. For example, in Venezuela and Colombia, arepas are highly appreciated. Then in Central America, the pupusa is queen. In Guatemala, thick tortillas are common; in Mexico, there are tortillas made of black, red, white or yellow corn. Also, there are bocoles, another round thick tortilla-like delicacy made of corn. Each of these delicious round corn foods developed within their own context; therefore, each typically reflects the flavors of its own region, its species and vegetables, such as avocado filled arepas in northern South America and Panama or loroco flowers in Central American pupusas. Many of these round corn delights are eaten any time of the day, breakfast, lunch or dinner or simply as a snack between meals. Many of them are easy to eat on the go, excellent food for traveling. In northern regions of South America, most especially Venezuela and Colombia, arepas are an everyday fare for many. Panama just to the north enjoys this treat as well. What is an arepa? This hearty dish is a round frequently grilled and almost flat corn cake. Once it is cooked, it can be filled with avocado, queso fresco or meat, just to mention some possibilities. Another variation is to fry them instead of being grilled. How is the arepa connected to the history of these regions of Latin America? Before colonial times and political division, indigenous people shared this vast region and shared the use of corn and other products. Roots of arepas are indigenous. Its name is believed to originate from the Cumanagoto word ‘erepa’ which translates as corn. This is why I treasure each bite when I have the opportunity to enjoy an arepa. While arepas are traditional in northern South America and Panama, as we move further north to Central America, flat corn dishes take on the form of pupusas. This delectable round corn cake, larger than arepas, is filled with queso fresco, loroco, ayote, fried beans and/or chicharrones, made by hand and grilled. In addition to corn, there is another variety of pupusas but made with rice flour. Personally, I still prefer the ones made of corn. To accompany a pupusa, it is usually eaten along with curtido, a slaw made of shredded carrots, cabbage, onions, oregano, and tomato salsa to taste. Large jars of curtido are passed around and served up alongside your delicious round corn pupusa. How do I like my pupusas? For me, pupusas taste better when eaten as a finger food and among friends. Isn’t good food usually enjoyed more with the accompaniment of those we enjoy around us? What are the origins of the name of this wonderful round corn cake? The origin of the word pupusa or popotlax seems to be a combination of two Nahuatl-Pipil words. Popotl means filling or stuffing, and tlaxcalli means tortilla. Pupusas are so popular that El Salvador has made them its national dish and celebrates el Día de la pupusa on the second Sunday of November each year. And, it’s not just El Salvador; pupusas are also extremely popular in Honduras as well. As we go further north yet to Mexico, we can enjoy bocoles, another round corn cake which is also grilled en un comal. They are made by hand and the masa is mixed with manteca de res. I personally mix the masa with vegetable oil or butter. Almost flat, bocoles are filled and then cooked or they can be filled after being grilled. Traditional fillings include queso fresco mixed with a chile ancho paste, refried beans and yerbabuena, eggs, avocado, and/or meat. Historically and thriving today, bocoles are an indigenous food of the Huastec people in Mexico; the Huastec people live in what we know today as the states of Hidalgo, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro and the Northen region of Veracruz. My mother belongs to the Huasteca veracruzana and I grew up eating homemade bocoles filled with queso fresco and chile ancho paste. I truly enjoy the memories of my mother and grandmother warming up the comal, and the delicious earthy aroma of grilled bocoles filling the air. We often take with us childhood flavors, nuestros sabores de niñez, wherever we go and whether we are aware of it or not. Here in the US, disfruto, I enjoy seeing the many different family restaurants where I can order wonderful pupusas or arepas. I haven’t yet found a place to order bocoles, but at home, usually on a quiet weekend, I honor la abuela every time I summerge my hands en la masa to make bocoles. Gracias, abuela. Inspired by my grandmother, here is my recipe for bocoles: Los bocoles Prepare masa harina, about 2 cups (follow package directions) Add ½ a teaspoon of soft butter Filling Rehydrate 2 ancho peppers (I love the flavor of ancho peppers, but you can only use one).

Mix with crumbled queso fresco, about ½ cheese, I use queso fresco that I am able to find at the supermarket.

Make masa balls, about the size of golf ball, make an indention put the filling in the indention and then close it up. Flatten it into a small cake and grill it. Enjoy!

📷Pictures of pupusas and bocoles by Xánath Caraza. Picture of arepas courtesy of Paola Ramírez.

Follow the Smithsonian Latino Center on Instagram @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via twitter @SLC_Latino.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stay tuned as we follow Carmen Lomas Garza installing her #Ofrenda at the National Museum of American History. We will be streaming LIVE throughout the day via the #SLC_Ustream Channel #latinidadengrande #mylatinostory #dayofthedead

0 notes