#my initial idea is she is interning as a journalist or maybe assistant editor of a magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

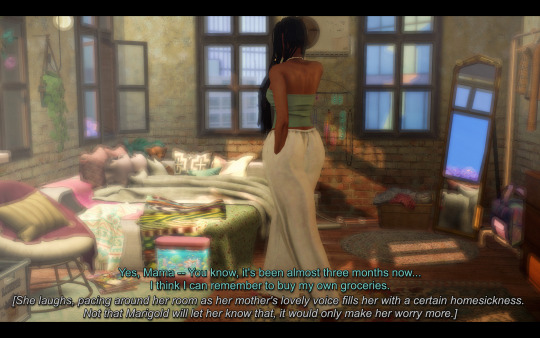

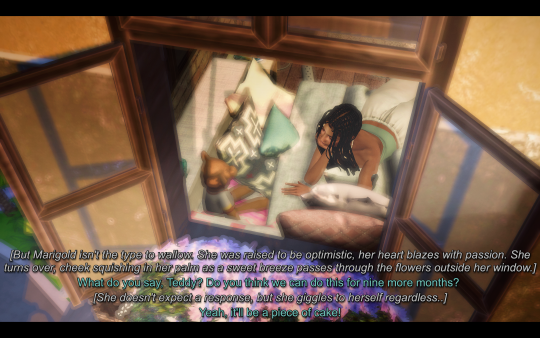

𝕄𝕒𝕣𝕤' ℝ𝕠𝕠𝕞 - 𝟞:𝟚𝟘 ℙ𝕄 ⋆⁺𖤓₊⋆

[Marigold's phone begins to ring again, the third time in the past twenty minutes. A yawn escapes her, old floorboards creaking as she walks through the shoddy curtain into her bedroom.] Marigold: Yes, Mama -- You know, it's been almost three months now...I think I can remember to buy my own groceries. [She laughs, pacing around her room as her mother's lovely voice fills her with a certain homesickness. Not that Marigold will let her know that, it would only make her worry more.] Marigold: Nine more months, and I'm home...if they don't end up hiring me! [Marigold's heart melts as her mother reassures her, pressing a few kisses through the phone.] Marigold: I love you always...I'll be sure to facetime you and Papa tomorrow morning. [Mattress springs squeak as she flops down onto her bed. She can't shake the melancholy, despite living her dream. To describe her life in the city thus far, the two words tied are fulfilling, and lonesome.] [But Marigold isn't the type to wallow. She was raised with optimism, and her heart blazes with passion. She turns, cheek squishing in her palm as a sweet breeze passes through the flowers outside her window.] Marigold: What do you say, Teddy? Do you think we can do this for nine more months? [She doesn’t expect a response, but she giggles to herself regardless.] Marigold: Yeah, it'll be a piece of cake!

#the sims 4#sims 4#ts4#s4#sims#simblr#sim: mars#story tag#my angel#yeah she talks to her stuffed animals what about it#tried out different editing w/ her#bc her world is SO colourful in comparison to my other ocs#she gets a window shot too <3#the point of this is she's a cutie patootie#actual sunshine dont stare too long you'll go blind#struggled to choose a song I have so many for her already!!#put your records on is always a vibe tho#and I think it fits her rn too ;-; <3#my initial idea is she is interning as a journalist or maybe assistant editor of a magazine#she misses home she misses her family terribly but it is only the beginning of her life in the city WOOOOO#I redid the text on these so many times so if there's any mistakes I am SORRYYY

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

NONFICTION

‘She Said’ Recounts How Two Times Reporters Broke the Harvey Weinstein Story

ImageJodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

Jodi Kantor and Megan TwoheyCreditCreditMartin Schoeller

BUY BOOK ▾

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Susan Faludi

Sept. 8, 2019

SHE SAID

Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement

By Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

Tell the truth: Do you really need to hear more about Harvey Weinstein? The open bathrobe, the hotel hot tubs, the syringes of erectile-dysfunction drugs delivered by cowed assistants, the transparent requests for “a massage,” the ejaculatory exhibitions — it’s not just indictable, it’s … ick, simultaneously pathological and pathetic.

Which explains the reluctance I felt sitting down to read “She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement,” wherein the New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey revisit at book length their investigative reporting on Weinstein, promising a “substantial amount” of new information. New information? More than 80 women have come forward to recount their encounters with the Oscar-award-monopolizer-and-patron-of-progressive-causes-turned-Tinseltown’s-über-ogre, the beast whose fleshy unshaven headshot every famous Hollywood beauty knows to hate, and whose trial has now been rescheduled for January to allow for additional testimony against him. What new gruesome details do we need?

But “She Said” isn’t retailing extra helpings of warmed-over salacity. The authors’ new information is less about the man and more about his surround-sound “complicity machine” of board members and lawyers, human resource officers and P.R. flaks, tabloid publishers and entertainment reporters who kept him rampaging with impunity years after his behavior had become an open secret. Kantor and Twohey instinctively understand the dangers of the Harvey-as-Monster story line — and the importance of refocusing our attention on structures of power. When they at last confront Weinstein, in a Times conference room and later on speakerphone, he’s the mouse that roared, the Great and Powerful Oz turned puny humbug, swerving from incoherent rants to self-pitying whimpers (“I’m already dead”) to sycophantic claims of just being one of them. (“If I wasn’t making movies, I would’ve been a journalist.”) He’s loathsome and self-serving, but his psychology is not the story they want to tell. The drama they chronicle instead is more complex and subtle, a narrative in which they are ultimately not mere observers but, essential to its moral message, protagonists themselves.

ADVERTISEMENT

[ This book was one of our most anticipated titles of September. See the full list. ]

Kantor and Twohey broke the Weinstein story. Their 3,300-word Times article on Oct. 5, 2017, aired allegations against him that had been piling up as whispers and rumors for 30 years. That report, and the ones to follow, were grounded in scores of interviews with actresses and current and former employees, supplemented by legal filings, corporate records and internal company communications that documented a thick web of cover-ups, bullying tactics and confidential settlements. It was bravura journalism.

“We watched with astonishment as a dam wall broke,” Kantor and Twohey write of the response to that first article. A day after it was published, so many women phoned The Times to report allegations of sexual harassment and assault against Weinstein that the paper had to assign additional reporters to handle the calls. On Oct. 10, another round of women, including marquee names like Gwyneth Paltrow, Angelina Jolie and Rosanna Arquette, went public in a second article in The Times. Three weeks later, a third article detailed still more accounts of sexual abuse by Weinstein, spanning the globe and dating back to the 1970s. “This has haunted me my entire life,” said 62-year-old Hope Exiner d’Amore, who recounted being raped by Weinstein when she was in her early 20s.

This series of articles in many ways ignited the #MeToo movement, already smoldering in the atmosphere of frustration after reports of Donald Trump’s alleged sexual predations (a story that Twohey broke with another reporter) and the release of the “Access Hollywood” tape failed to slow the reality star’s march to the White House. Their reporting, Kantor and Twohey recall in “She Said,” seemed to operate as a “solvent for secrecy, pushing women all over the world to speak up about similar experiences.”

And a solvent for the structures that enforced that secrecy. A day after the first story came out, a third of the (all-male) board of the Weinstein Company resigned and the remaining members put Weinstein on leave. Two days later, he was fired. Within a year, his corporation declared bankruptcy — and, as part of the Chapter 11 filing, released employees from nondisclosure agreements.

Image

Credit

What explains the company’s decades of inaction? Answering that question, and parsing the ways that such entities and their centurions functioned as Weinstein’s shield, is the prime focus of “She Said.” The guardians the authors unmask aren’t only the obvious ones. Yes, Weinstein’s board members looked the other way long after they knew; yes, The National Enquirer and Black Cube security snoops deep-sixed damaging accounts and shut down whistle-blowers. Yes, Weinstein’s brother, Bob, the company’s co-founder, kept mum beyond all reason — even after Harvey had punched him in the face. But there was also the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which often kept its settlements secret. And David Boies, the lawyer admired for championing gay marriage before the Supreme Court, who served as Weinstein’s personal consigliere and tried to squash every threat of bad press. And Linda Fairstein, the celebrated Manhattan sex crimes prosecutor, who, after an Italian model reported to the New York City police that Weinstein had groped her, brokered connections between Weinstein’s legal team and the lead prosecutor and tried to discredit the woman’s allegation to Twohey.

ADVERTISEMENT

[ “She Said” names some of the people who helped Harvey Weinstein evade scrutiny. ]

And then there was Gloria Allred, the crusading feminist lawyer, whose law firm, in 2004, negotiated a nondisclosure agreement for one of Weinstein’s victims; the firm pocketed 40 percent of the settlement. “While the attorney cultivated a reputation for giving female victims a voice,” Kantor and Twohey write, “some of her work and revenue was in negotiating secret settlements that silenced them and buried allegations of sexual harassment and assault.” Allred went on to do the same with women who had been abused by the Fox News host Bill O’Reilly and the Olympics gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar. In 2017, after a group of lawyers in California persuaded a state legislator to consider a bill that would ban confidentiality clauses muzzling sexual harassment victims, Allred denounced the move and threatened to go on the attack. The legislator, Connie Leyva, quickly shelved the idea. (A year later, Leyva introduced such a bill and it was signed into law.)

Maybe the most appalling figure in this constellation of collaborators and enablers is Lisa Bloom, Allred’s daughter. A lawyer likewise known for winning sexual-harassment settlements with nondisclosure agreements, Bloom was retained by Weinstein (who had also bought the movie rights to her book). In a jaw-dropping memo to Weinstein, Bloom itemized her game plan: Initiate “counterops online campaigns,” place articles in the press painting one of his accusers as a “pathological liar,” start a Weinstein Foundation “on gender equality” and hire a “reputation management company” to suppress negative articles on Google. Oh, and this gem: “You and I come out publicly in a pre-emptive interview where you talk about evolving on women’s issues, prompted by death of your mother, Trump pussy grab tape and, maybe, nasty unfounded hurtful rumors about you. … You should be the hero of the story, not the villain. This is very doable.”

“She Said” contains a second story of what’s doable against great odds: how two reporters with no connections in Hollywood and with almost no one willing to go on the record were able to penetrate this omertà and expose what lay behind it to public scrutiny. This is the book’s deeper level, the story of getting a story, signaled in the choice of chapter titles like “The First Phone Call” and “‘Who Else Is on the Record?’” Kantor and Twohey have crafted their news dispatches into a seamless and suspenseful account of their reportorial journey, a gripping blow-by-blow of how they managed, “working in the blank spaces between the words,” to corroborate allegations that had been chased and abandoned by multiple journalists before them. “She Said” reads a bit like a feminist “All the President’s Men.”

Kantor and Twohey take us through the time-consuming, meticulous and often go-nowhere grunt work that’s intrinsic to gathering evidence, winning the trust of gun-shy victims and maneuvering past barricades that block the path to a publishable article. Along the way, we witness how much institutional support such a protracted effort requires. Kantor and Twohey make a point throughout the book of stressing their reliance on a multilayered editorial team, from rigorous young research assistants like Grace Ashford, who combs through government employment data and tracks down a key former assistant from the late 1980s at Miramax, Weinstein’s film production company, to seasoned elder hands like the Times investigative editor Rebecca Corbett. “Sixtysomething, skeptical, scrupulous and allergic to flashiness or exaggeration,” Kantor and Twohey write of her, “but so low profile that she barely surfaced in Google search results. Her ambition was journalistic, not personal.” The night before the first article ran, Corbett remained in the newsroom until dawn, weighing and reweighing every word.

In this way, “She Said” is a dead-on description of what makes so-called “legacy” journalism so powerful. Ironically, the #MeToo movement that Kantor and Twohey’s articles about Weinstein helped launch promulgates an opposite message: that the best way to bring injustice to light is to get rid of the “gatekeepers” and let rip on Twitter, that we’ll only get to the “truth” when the Establishment is brought down and no one is in charge.

[ Read: “I’m Harvey Weinstein — you know what I can do.” ]

It may be, as the political writer Lee Smith argued in The Weekly Standard, that some journalists had protected Weinstein partly out of a craven illusion that the Hollywood rainmaker would someday make rain for them, buying their articles for high-grossing films. And no doubt the #MeToo movement has prompted the mainstream media to take these stories more seriously. Would Vanity Fair’s editor today omit allegations of sexual assault from a profile of Jeffrey Epstein, as happened in 2003? Nonetheless, the big-league sexual predators who have been brought to justice in the #MeToo era have been brought there not by internet whisper campaigns but by good old-fashioned reporting: O’Reilly by The Times, Nassar by The Indianapolis Star, Epstein by The Miami Herald, Roy Moore by The Washington Post, Weinstein by The Times and The New Yorker. “The Weinstein story had impact,” the authors note, “in part because it had achieved something that, in 2018, seemed rare and precious: broad consensus on the facts.”

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s an implication here: The answer to institutionally protected predation isn’t the anti-institutionalism of social media and viral tweets, but a powerful counter-institution capable of mounting a rigorous investigation, run by, yes, gatekeepers. Not spelled out but amply evident in Kantor and Twohey’s reckoning is the importance that those gatekeepers be female as well as male. In 2013, Jill Abramson, then The Times’s executive editor, promoted Corbett and another woman to the paper’s senior editorial staff, making the masthead 50 percent female for the first time in history. What happens when you get that kind of sisterhood is familiar to any spectator of the Women’s World Cup. Watching Kantor and Twohey pursue their goal while guarding each other’s back is as exhilarating as watching Megan Rapinoe and Crystal Dunn on the pitch.

Toward the end of the book, Kantor and Twohey devote two chapters to Christine Blasey Ford and her decision to air her sexual-assault allegations against the Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. This, and the book’s finale, “The Gathering,” seem appended, an anticlimactic climax. In “The Gathering,” the reporters assemble 12 of the sexual abuse victims they interviewed (including a McDonald’s worker, Kim Lawson, who helped organize a nationwide strike over the fast-food franchise’s failure to address sexual harassment) at Gwyneth Paltrow’s Brentwood mansion to talk, over gourmet Japanese cuisine, about what they’ve endured since going public with their charges. The testimonials inevitably descend into platitudes about personal “growth” and getting “some sense of myself back.” At one point, Paltrow starts crying over the way Weinstein had invoked his support for her career to get women to submit to his advances, and Lawson’s friend (a McDonald’s labor organizer who came with her so she wouldn’t feel alone in a room full of movie stars) hands the actress a box of tissues.

These therapeutic scenes paste a pat conclusion onto a book that otherwise keeps the focus not on individual behavior or personal feelings but on the apparatuses of politics and power. At the least, though, the contrast throws into relief how un-pat, instructive and necessary “She Said” is. It turns out we did need to hear more about Weinstein — and the “more” that Kantor and Twohey give us draws an important distinction between the trendy ethic of hashtag justice and the disciplined professionalism and institutional heft that actually got the job done.

Susan Faludi is the author of “Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women” and, most recently, “In the Darkroom.”

SHE SAID

Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement

By Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

310 pp. Penguin Press. $28.

0 notes