#my area on november 2nd 1881

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

IT'S NOT GREEK INDEPENDENCE DAY

THERE IS NO GREEK INDEPENDENCE DAY!!!!!

TODAY IS THE CELEBRATION FOR THE ANNIVERSARY OF THE START OF THE GREEK REVOLUTION OF 1821 (and the religious holiday for the Annunciation)

PLEASE STOP CALLING IT INDEPENDENCE DAY

#texterna#this is my biggest pet peeve#there is no independence day because different parts of greece gained independence different years#like the earliest parts gained independence January 27 1827? somewhere then#my area on november 2nd 1881#some other areas as late as 1945#so yeah.....

1 note

·

View note

Text

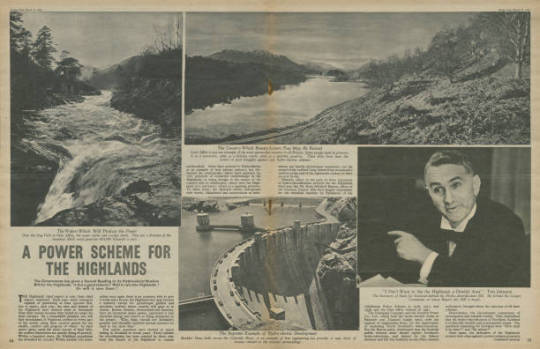

Tom Johnston, one of Scotland’s best known Secretaries of State, was born on November 2nd 1881.

Now and again I bend the rules and cover a politician in my posts, Tom Johnston is such a case, a remarkable man who lived to see the Highlands transformed, bringing electricity to regions who had, until then had very little or none in the years up to Woerld War Two,

Johnston was the son of David Johnston, a grocer, and his wife, Mary Blackwood, he was born in Kirkintilloch in and educated at Lairdsland Public School then at Lenzie Academy.

Tom then entered the University Glasgow where he became interested in politics and stood successfully for a local election in 1903 representing the Independent Labour Party.

In 1906, thanks to inheriting a printing press from a relative, he was able to set up The Forward, a radical weekly paper that reflected his Fabianism and teetotalism. He remained editor until 1933. It was in the early days of running the paper that he matriculated at the University as a mature student aged twenty-three.

In 1907 he continued his education and took a class in Moral Philosophy and gave his address as the Student Settlement, a pioneering student association interested in social improvement. The following year he enrolled for Economics, but he left without graduating.

He married Margaret F. Cochrane in 1914 and they were married for over 50 years, they had two children.

During the The First World War he advocated peace and attacked war profiteers. After the war he stood for parliament, and in 1922 won West Stirlingshire for Labour. The period of his greatest achievement was during the Second World War. Churchill appointed him as secretary of state for Scotland in 1941. He worked with colleagues of all parties to galvanise the Scottish economy on a war footing.

It was Tom Johnston who was instrumental in creating the North of Scotland Hydro- Electric Board, his greatest achievement, handling rural Scotland's resistance and hesitation towards the project intelligently. Until the 1940s, many rural areas of Scotland outwith the Central Belt had little or no electricity supply. There were coal-fired steam-turbine and some diesel-driven power stations serving urban locations.

In the three decades following the Second World War, the Hydro Board's teams of planners, engineers, architects and labourers succeeded in creating an epic succession of electricity generation and distribution schemes that were world-renowned not only for successfully achieving their technical aims in very demanding terrain but for often doing so in an aesthetically inspiring manner. The economic and social benefits thus brought to all the people of Scotland, and especially those in rural areas, were immense and long-lasting

In 1920 he published the History of the Working Classes in Scotland and from 1950 to 1952 he served as President of the Scottish History Society.

The University of Glasgow conferred the degree of Honorary LLD in 1945. In 1948 he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Aberdeen. He was also Chancellor of Aberdeen University from 1951 until his death.

Thomas Johnston died on 5th September 1965 in Milgavie.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The seashore seems to be a potent spot for ghosts. Fishermen dread to walk anywhere near where a ship has foundered. The souls of drowned sailors are said to haunt such places and the ‘calling of the dead’ has frequently been heard . . .” James Turner, The Stone Peninsula, 1975.

Fishermen and sailors are a superstitious clan, and passing close to the watery graves of the lost members of their brotherhood was once treated with great trepidation. There was a fear that the voices of dead sailors would call their name and somehow lure them to their doom beneath the waves.

“I have been told that, under certain circumstances, especially before the coming of storms or at certain seasons, but always at night, these callings are common. Many a fisherman has declared he has heard the voices of dead sailors ‘hailing their own names’.” Robert Hunt, 1881.

Porthtowan is ‘just’ another cove on Cornwall’s wilder north coast but it is a favourite spot of mine. I especially like to catch it at low tide when the flat sand runs all the way to Chapel Porth. I walk the mile or so with the stark cliffs towering above me, then I return along the grassy top path, making a satisfying circular walk. The cliffs and bare downs here once bristled with mine buildings and hummed with hard industry but now Porthtowan beach is popular with surfers and families alike.

Like so many places in Cornwall however, strange legends and tragedy are never far away.

The Man in Black

There is a curious story about Porthtowan that would make a sailor’s blood run cold.

Once a fisherman was making his way home across the sand late one afternoon. The tide was far out leaving a wide band of smooth sand, the water calmly lapped towards the shore. Quite suddenly the man heard an unearthly voice coming from the waves.

“The hour is come, but not the man.”

The strange phrase was repeated three times. And then, just as the fisherman tried to see from where the voice was coming from, a figure appeared on the cliff above the beach. A silhouette of a man dressed in black.

As the frightened fisherman watched the dark figure seemed to listen for a moment, then suddenly he charged headlong down the steep incline, ran across the beach and dove into the sea, vanishing from sight. In another version of this tale as the man in black jumps into the sea the fisherman sees a ghostly sailing ship appearing out of the mist on the horizon.

The Dragon & the White Shuck

The towering hills between Porthtowan and Chapel Porth are almost completely devoid of trees. Barren and windswept, intensive mining has stripped the landscape. Little grows here and it can be a bleak and forboding place when a clammy sea mist rolls in.

“We descend over a stony waste, threading innumerable walls to Chapel Porth, a cove at the mouth of a deep moorland combe . . . for some miles the cliff tops are covered with heather. Porth Towan a larger but in other respects similar cove comes next. Both are more or less spoilt by mines.” John Lloyd Warden Page, 1897.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

There is a legend about this place which is particularly unusual, a one off perhaps, for Cornwall. Neither dragons or shuck are common here you see. And for those wondering, as I was one, a shuck is a huge, shaggy dog, normally black. A written description from 1888 claims that these hounds are sometimes headless but usually have a single ‘blazing eye’ in the middle of their forehead.

Their name apparently derives from an old English word ‘scucca’ meaning devil or fiend. Shucks are most common in East Anglia. It’s thought that they originated in Scandinavian folklore as a black hound of Odin and were brought to us here by the Vikings. The hound associated with our Cornish story was indeed monstrous in size, but it was apparently white, not black.

The myth tells us that back along, many moons ago, a fearsome dragon roamed the cliffs above Porthtowan, in an area known as Mile Hill. The scaly monster had his liar in a nearby cave in the cliff face and he spent his time terrorised the local people, as dragons often do.

One night however, according to tale, the dragon crossed paths with the Cornish White Shuck. A bloody battle ensued and against the odds the huge, mysterious dog defeated the dragon, who slunk off with his tail between his legs.

Legend has it that the spirit of that hound still haunts the wild clifftops above Porthtowan to this day.

Shipwreck of the Rose of Devon

On 16th March 1816 on the flat sands between Porthtowan and Chapel Porth a squadron of Iniskilling dragoons from had to beat off local miners with sticks. The miners were trying to board the brig Harriet that had run ashore on her way to Liverpool. Shipwrecks were once depressingly common on the Cornish coast. Many, like the Harriet, have been recorded on the stretch of coast close to Porthtowan, their stories written about in the papers, and rarely do they have a happy ending.

And so, the fate of the Rose of Devon that came to grief at Porthtowan is not for the fainthearted I am afraid.

On 28th November 1897 the waves were winter wild. The newspapers reported that sightseers had come from miles around to watch the roaring waters and the towering clouds of sea spray from the cliffs above Porthtowan beach, much as we do today.

As the light faded that day Coastguard West, who was on duty that weekend, took a last look at the churning waters and saw nothing in particular that concerned him. However, when West came down to the water at 6am the next morning something wasn’t right. There was wreckage pounding in on the incoming tide. And that wasn’t all.

To his horror he spotted first two and then four bodies rolling in on the waves or stuck in between rocks. West ran for help and within just a few minutes there were six bodies laid out on the sand. All but one of the drowned crew wore belts bearing the name ‘Rose of Devon’.

Image said to show the wreck of the Rose of Devon on Porthtowan beach: credit Cornish Memory

The Rose of Devon had apparently been driven onto the rocks by the raging gale. According to later reports the ship’s rockets and flares had been been hidden by the violent lightening and heavy rain that night.

The bodies of the crew were taken to a house near the beach and as the tide retreated later that day the shell of the 405 ton wooden barque was revealed stuck fast on the beach.

‘At dawn her shattered hull festooned with chains and ropes was stranded in the surf.’

The Rose of Devon was launched in Plymouth and owned by Onesimus Dorey of Guernsey. It was captained by George Borcher and had a crew of eleven. The rest of the men were eventually washed up, some weeks later, all along the coast. The body of George Borcher washed up at St Agnes.

The inquest was held on the six recovered bodies at Porthtowan two days later on 1st December and a self-evident verdict of ‘found drowned’ was given on each by coroner Laurence Carlyon. The newspapers of the day detailed each of the crew, including their physical descriptions, tattoos and various obvious injuries but no names were recorded. However, another more disturbing issue was also discussed. The condition of the bodies since they had been washed ashore.

Apparently in the days after the wreck the dead crew had been moved to an unprotected outhouse, where they had been laid out on a dirt floor and left uncovered. And the remains of the sailors had been attracting the attention of rats.

“Coastguard West said they could get the bodies removed into a house where there was a wooden floor but that they would have to obtain . . . permission first. He added that he and his colleagues knocked on the door of the shed in which the bodies were every time they passed in order to frighten the rats away.” The Cornishman, 2nd Dec 1897.

None of the men were from Cornwall and so there was no one to claim their bodies. In years gone by the practice had been to buried the drowned on the clifftops close to where they had been discovered but that had been outlawed. It was now the responsibility of the parish to pay for the sailors’ funeral. There appears to have been some debate over which parish, Illogan or St. Agnes, was to take the bodies.

As it was the funerals of six of the men (Captain Borcher’s family claimed his remains) were eventually held at Mount Hawke on 9th December 1897. The West Briton newspaper reported that hundreds of local people turned out to pay their respects and each coffin was draped with a flag. Some time after a granite memorial was raised in the graveyard to mark the spot where the unfortunate crew had been laid to rest. The inscription reads: F. Eliot, H. Martel, C. Palzard, W. Toll and 2 others”.

Local man Jerry Strongman, who grew up in Porthtowan, recalled seeing the remains of the wreck of the Rose of Devon at low tide during his childhood in the 1960s. As far as I am aware no trace of it can be found today.

I provide all the content on this blog completely free, there’s no subscription fee. If however you enjoy my work and would like to contribute something towards helping me keep researching Cornwall’s amazing history and then sharing it with you then you can donate below. Thank you! [wpedon id=17835]

Further Reading:

St Agnes Beacon

Cavalla Bianca – an unusual wreck in Penzance

Walking Opportunities:

Porthtowan to Chapel Porth circular walk

Porthtowan – ghosts, dragons & shipwrecks "The seashore seems to be a potent spot for ghosts. Fishermen dread to walk anywhere near where a ship has foundered.

2 notes

·

View notes