#mott warsh Gallery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

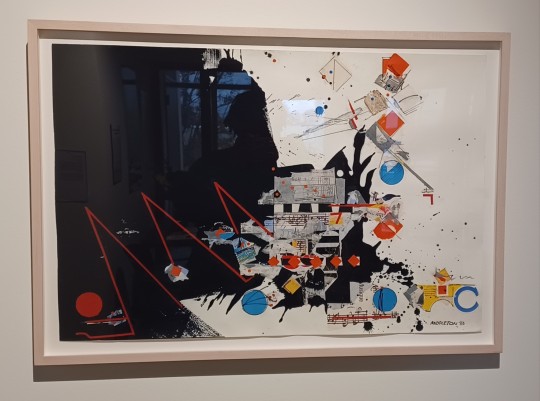

Highlights from Game Changers: Sam Gillam and his Contemporaries

S, 1970

Paper Theater, 1991

Coal and Taper, 1977

Red Slatt, 2003

I don't have the label for this.

December, 1988

A few of the Contemporaries

Raymond Saunders; This and That of What Wants to be Beauty, 2005

Mildred Thompson: Untitled, no date

Betye Saar; Return to Dreamtime, 1990

#mott warsh Gallery#charles stewart mott#contemporary art#sam gillam#black artist#black contemporary art#abstract art

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Women of Color Find Their Rightful Place in the History of American Abstraction

Mildred Thompson, “Magnetic Fields” (1991) oil on canvas, triptych 70.5 x 150 inches (art and photo courtesy and copyright of the Mildred Thompson Estate, Atlanta, GA)

KANSAS CITY — Art history rarely gets it right the first time, but the established accounts of American abstraction that canonized particular artists before the paint on their work was dry, is proving particularly vulnerable to criticism. Whether due to a rejection of the staggering certitude of Greenberg’s formalism, the deep veins of racism/classism/sexism running through twentieth- century criticism and curation, or the closely guarded access to institutions of art, these historical narratives are undergoing an intensive curatorial corrective.

An important achievement towards this end is Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today, organized by the Kemper Museum of Art in Kansas City. The exhibition, generously funded by the NEA and the Andy Warhol Foundation, is on view through September 17, after which it travels to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. According to the Kemper, this is the first museum exhibit in the US to show abstract artwork created exclusively by women of color. Stylistically varied and teeming with formal flights of bravura, the exhibit seems to engage the magnetic forces of the Mildred Thompson painting from which it takes its name.

Alma Woodsey Thomas, “Orion” (1973) acrylic on canvas, 60 x 54 inches (courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. © Alma Woodsey Thomas, photo by Lee Stalsworth)

Magnetic Fields follows closely on the success of the 2016 Women of Abstract Expressionism, at the Denver Museum of Art, which I viewed. That show was, in itself, a convincing challenge to the popular conception of Abstract Expressionism as a boy’s club. The well known 1950 Life magazine photograph of the Irascible 18, aka the New York School included only one woman, Hedda Sterne, who later would note that all the men were furious about her inclusion, thinking her mere presence would detract from the profound seriousness of their endeavor.

Installation view of Magnetic Fields Maren Hassinger, “Wrenching News,” (2008) (work on floor); Abigail DeVille, “Harlem Flag,” (2014) partial view of “Magnetic Fields” (1991) by Mildred Thompson (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The Denver show, which traveled to Charlotte, NC and Palm Springs, CA, featured mostly exemplary work by 12 women within the circle of the Abstract Expressionists. Of course, as in any broadly conceived group show, many were left out. Someday, for instance, I’d like to see Janet Sobel’s 1944 drip paintings — admired by Pollock and which Greenberg would later cite as the first instance of ”all-over” painting — placed within an Abstract Expressionist context. But it was an eye-opener to see the bold yet underappreciated works of Judith Godwin, Perle Fine, and other even less known women from the period.

Magnetic Fields opens my eyes even further, pointing out work by Alma Thomas, Mildred Thompson, and Howardena Pindell that could expand the Abstract Expressionist canon even further. To be clear, Magnetic Fields focuses on work from the 1960s to the present, but all three of these women were working in New York in the forties and fifties, in the abstract expressionist style, right alongside their better known colleagues. Like those in the Denver Museum exhibition, these artists struggled against derision from their male peers, lack of access to the art institutions, holding down multiple jobs with paltry wages, and the demands of raising a family.

Installation view of Magnetic Fields (left to right) Alma Thomas, “Orion,” (1973); Brenna Youngblood, “YARDGUARD” (2015); Mildred Thompson, “Magnetic Fields,” (1991) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

But add a history of racism — both insidious and blatantly overt — and the achievements of the 21 African American women in Magnetic Fields add some serious grit to the much mythologized heroics of Life’s portrait of the 17 men topped off by the rather lonely figure of Hedda Sterne. The courage, tenacity, and fortitude of these women are described in their stories and those qualities reverberate in the artworks on display. In a panel discussion at the Kemper, Lilian Thomas Burwell described her lyrical, shaped paintings in the context of her own family’s struggle during the Northern migration. In a 2006 artist statement, Pindell wrote of the small circular shapes comprising her mixed media abstractions, making a connection to childhood memories of strange red circles drawn on the bottom of root beer mugs “to designate that the glass was to be used by a person of color.” These small, confetti-like shapes comprise much of her work from the late seventies and early eighties. Here, in “Autobiography: Japan (Shisen-do, Kyoto)” (1982) they are combined with scraps of tickets, exhibition guides and other ephemera into a crusty, dimpled, and obsessively constructed self image.

It wasn’t until 1975 when Alma Thomas, who worked out of her kitchen for most of her career, became the very first black woman to have a solo show at the Whitney. She was 80 years old. The perseverance behind such stories continue to inspire the careers of the younger artists in Magnetic Fields. As the title of Mary Lovelace O’Neal’s monumental 1991 abstraction reads, “Racism is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere.”

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, “Racism is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere” (1993) acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 86 x 138 inches (photo courtesy of the Mott-Warsh Collection, Flint MI. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal)

Importantly though, resistance to the work on display here was not limited to the white community. The Black Arts Movement, formally established in 1965 by a group of politically motivated poets, artists, and musicians, had little use for abstract painting. Deeply connected to the Black Power Movement, BAM was committed to the artistic celebration and manifestation of “the goodness and beauty of Blackness.” Scholar and co-founder of the group, Larry O’Neal, wrote: “The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world.” Abstraction, in the view of O’Neal and others in the arts movements, was a white idea. In EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art, author Kellie Jones quotes Howardina Pindell’s description of an event in the late sixties: “I remember going with my abstract work to the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the director at the time said to me, ‘Go downtown and show with the white boys.’” Pindell added that William T. Williams and Al Loving met with the same kind of response. “We were basically considered traitors because we didn’t do specifically didactic work.”

Shinique Smith, “Whirlwind Dancer” (2014–2017) ink, acrylic, paper and fabric collage on canvas over wood panel 96 x 96 x 3 inches, collection of Leslie and Greg Ferrero, courtesy of David Castillo Gallery, Miami, (photo by E. G. Schempf; © Shinique Smith)

Fifty years later it is notable that, didactics or no, the work of these women can be said to express most vibrantly, “the goodness and beauty of Blackness,” as well as its enrichment of the larger visual culture.

Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today, continues at the Kemper Museum of Art (4420 Warwick Boulevard) Kansas City, MO through September 17.

The post Women of Color Find Their Rightful Place in the History of American Abstraction appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2g0E3Ti via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Highlights of

From Her Perspective: Intersections of Gender & Race

Bearing, 2006,

Bradley McCullum & Jacqueline Terry

African/American, 1998

Kara Walker

Untitled (from the Kitchen Table Series), 1990

Carrie Mae Weems

Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, 1998

Renee Cox

Baby Back (American Family), 2001

Renee Cox

Rozeal

Painful,the appearance of a dime in the cling (after Yashitashi's painful, the appearance of a prostitute of the Kansei era), 2006

Mrs. O'Dell Broadway and the Breakfast Program, 2009

Michele Tejoula Turner

Histology of Different Classes of Uterine Tumors, 2006

Wangechi Mutu

Corridor Day, 2003

Lorna Simpson

#Mott Warsh Gallery#MW Gallery#flint michigan#from her perspective#art show#charles stewart mott#carrie mae weems#kara walker#bradley mccullum#jacqueline terry#rozeal#iona rozeal brown#renee cox#histology#feminism#wangechi mutu#black artist#photography#mixed media#lorna simpson#video art#sculpture#women artists#black women art

0 notes