#mosses from an old manse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[...] the intense morbidness which now pervaded his nature.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mosses from an Old Manse; from 'Egotism; Or, The Bosom Serpent'

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dirty Work 41

Warnings: this fic will include dark content such as bullying, familial discord/abuse, and possible untagged elements. My warnings are not exhaustive, enter at your own risk.

This is a dark!fic and explicit. 18+ only. Your media consumption is your own responsibility. Warnings have been given. DO NOT PROCEED if these matters upset you.

Summary: You start a new gig and find one of your clients to be hard to please.

Characters: Loki

Note: it's thursday and i'm thirsty.

As per usual, I humbly request your thoughts! Reblogs are always appreciated and welcomed, not only do I see them easier but it lets other people see my work. I will do my best to answer all I can. I’m trying to get better at keeping up so thanks everyone for staying with me.

Your feedback will help in this and future works (and WiPs, I haven’t forgotten those!) Please do not just put ‘more’. I will block you.

I love you all immensely. Take care. 💖

You have no tears left. When you’re still and silent, standing in Odin’s arms, slumped against him, the birds sing a little louder and the sun shines a little bright. You feel almost cleansed despite the hollow at the pit of your stomach. You lift your head and wipe your damp cheeks as he slowly lets his embrace fall away from you.

You sniffle and peer back through the garden, towards the house. You’e not ready to face them all, not with puffy eyes and a heavy heart. Odin pats your shoulder gently, rubbing your arm as he coos your name.

“I have something else to show you,” he says and offers his hand.

You take it and gulp down the last of your grief. He turns you away from the great Odinson manse and leads you around the fountain. Leaves rustle softly and the water trickles soothingly. He guides you down a path hidden behind a cluster of bramble, overgrown with moss and ivy, littered with winged samara and sprouting blooms.

The noise of the fountain fades behind you as you enter an archway formed by outstretched maple branches, canopied in the spring leaves. There’s a small structure ahead shrouded in purple wisteria. A gazebo, smaller than that on Laufeyson’s property, forged in stone with rounded windows upon each side. Within, the walls have benches jutting out, another doorway opposite the entrance, looking out into a shadow swath of untrimmed foliage.

“It is old, a bit unkempt, much like myself,” he chuckles as he lets you go.

“It’s beautiful,” you preen as you admire the neat lines between each stone block, “wonderful… I… I love it.”

“It’s a perfect hiding place,” he muses, “a perfect place to have one’s breakfast without disturbance.”

You turn to him, a question stitches between your brows.

“I will fetch you tea? Yes? Perhaps some fruit and something more substantial?”

“I…”

“Dear, you think overly much of others and not enough of yourself. Sit, enjoy your solitude while you can, and I will return with all you need,” he insists.

“I can’t, Mr. Lauf–”

“You let me worry for my son,” he interjects. “I’ve no doubt his part in your despair.”

You don’t argue further. You wouldn’t dare. You lower your head and sit along the stone bench against the wall and turn to peer out the window. It is wonderful there. Like a little world of your own.

You glance over but he’s already gone. You barely even heard him with the buzz of insects and scratch of sneaky critters all around. You turn back to the long window and watch a dragonfly skim along the ground, whizzing up, down, and back and forth. It’s as if you escaped into a book you read as a girl, where everything was magical and spectacular. You don’t think you’ll get a happy ending though.

Your mind wanders through the greenery and back to the house. The bedroom, dark in the small hours of the night, laying awake, staring at the wall, Mr. Laufeyson’s warm breaths puffing into your neck. Those moments when he doesn’t seem so intimidating but remains perplexing. One moment, wrapped around you, the next toying with you like a puppet.

Your core tingles and you bend your legs on the bench, squeezing them together. The sensations swirl in your mind with the shower steam. As delightful as it all was, your heart rents with shame. The way he left you on the tile, the expectation you would get yourself up and go to him, ready to be used again. As always, you have a duty.

Mr. Laufeyson does not care for you as a person, you doubt you’ll ever be that in his eyes. You are just another possession, like his records on the shelf, or that telescope he polishes so vehemently. Just another number in his collection.

You hear a snap and blow away the anxiety as best you can. You can’t worry about it so deeply, you know what you agreed to. He has given what he’s promised; you’ve been fed, clothed, and housed. You need him more than he could ever need you.

You turn to the doorway as Odin appears again, a tray in his hands. He brings it to the next bench and sets it down. There’s a cup of tea and a stack of square waffles beneath a dusting of sugar and heaps of berries. It smells delicious as your mouth waters for a taste.

“I’ve brought this as well,” he stands straight and takes a book from under his arm, “I hope it will keep you entertained.”

“Oh?” You watch him set it down.

“Today is for you, dear, you won’t be disturbed, I will see to it,” he declares, “Walpurgisnacht approaches and we all must be ready for the spring. Lay the past behind so we can start again.”

You lower your eyes, “thank you, Odin.”

“No need for that,” he says, “I only ask that you do one thing for me,” he nears and pets your head. You peer up at him as you heart seizes. “You will be kind to yourself.”

“I… I’ll try.”

“You should take care of her,” he points to you, “I rather like her a lot and I hate to see those I care for suffer.”

You smile, “I will.”

“Better,” he grins and retreats, “I will be in to check on you periodically.”

“Thank you,” you call after him and he gives a half-salute before he’s off, whistling into the air.

You exhale and let the last of the tension slake away. You drag the tray close and cut into the fluffy stack. You remember how you always wanted a waffle maker. Instead, you always had the frozen waffles you slid into the old overheating toaster. These are much better, they’re sweet and oh so yummy.

Sitting there, in the small gazebo, amidst the wilderness, you feel like a bird in a nest. Safe, cozy, and alone.

✨

You lose yourself in the pages of the book. The sun shifts as you move with it, keeping the ink in its light as you imbibe every word like sweet nectar. It’s like staring in a mirror as you feed on the tale of one, Jane Eyre.

Your literary meditation is splintered by the sudden ripple of a shadow and the clearing of a throat; gentle, almost reluctant to tear through the serenity. You look up at Odin as he stands in the archway, a small curve amidst his thick white beard.

“Apologies,” he says as he comes forward to gather up the tray, “I’m afraid it’s time.”

You deflate and close the book. You stand and hold out the book, “I can get all that.”

“No, no, I can manage,” he assures you, “and that is for you, dear. Keep that as your own.”

“I couldn’t–”

“You have some to go, haven’t you?” He eyes the book, “please, I have enough books.”

You look down at the book and hug it. It’s like a new best friend. You just want to spend all your time amidst its pages.

“Thank you.”

“Whatever you need,” he backs out of the gazebo, “come with me now. Let us put our masks on.”

You giggle and follow him. He says it so well. It’s like slipping back into a costume. You feel the peace chipping away and the tension once more has you rigid. Back to the real world.

“Now, we cannot give ourselves away,” he halts just out of sight of the veranda, “I shall go ahead and you will follow that path,” he turns and nods behind the row of hedges, “follow it around the front and you may slip in.”

“Oh, uh…” You blink and look over your shoulder, “that way?”

“Yes, it will take you right around to the front door.”

“Right, thank you… again.”

He bows his head and steps forward. You turn off in your own escape as the slippers on your feet clap against the ground. You come out in the golden sunshine and tramp across the stonework of the arced drive. As you come up the steps, the door opens from within. You stop at the middle stare and gape up.

“There you are,” Mr. Laufeyson greets, almost an accusation, “where’ve you been off to?”

Your brows pop up and you peer around, “reading.”

“Reading? You couldn’t do so in your room?” He challenges.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Laufeyson. I broke the rules.”

“You broke the rules– get inside,” he points you inside as he steps back. You obey and he snaps the door at your entrance, turning towards you with a finger in the air. “Is that all you have to say?”

“Yes, Mr. Laufeyson, I’m very sorry.”

He sighs and drops his hand, gripping his hip, “where were you reading?”

“Outside.”

“Outside– be straight, where?”

“In the garden,” you say plainly, lips down turned, “I only wanted to watch the butterflies.”

You look up at him, a pout in your lower lip, and bat your lashes. You clutch the book tighter and his eyes fall to squint at it. He reaches and curls his fingers around the top, wiggling it free. He flips it over to read the spine.

“This is a first edition,” he states as he examines, “where did you find this?”

The disbelief in his voice makes you nervous. First edition?

“Is it very old?” You ask.

He winces and looks at you, his green eyes lit, “1847… I’d say so.”

“Oh?” You bat your lashes.

“Not in its original form,” he turns it over, “it’s been rebound into a single volume. The first print was in three parts and this cover… it can’t possibly be so ancient.”

You gulp and purse your lips.

“So I have to wonder, where you found this,” he sneers at you.

“Well, I… your father gave it to me.”

“Gave it to you? To read? He lent it to you?”

“Um, he just said… to keep it as my own,” you shrug.

“Do you--keep it? A first edition Bronte?” He sounds ready to explode, “so that is where you’ve been? With my father?”

“I saw him, Mr. Laufeyson, but I was mostly alone,” you sniff, “I shouldn’t have gone out. I’m sorry. Again.”

“Is that all you’re going to say? Sorry, sorry, sorry?”

You nod, “sorry.”

He closes his eyes and pinches his nose, “you will stay close.” He offers the book back to you, “put this away and put on some proper shoes,” he looks down at the oversized slippers, “I’ve some errands to run for mother and you will come along. Do your duty.”

✨

Mr. Laufeyson is quiet throughout the drive. So are you. You accept your penance and roil in the thick silence, fingers twiddling and twining restlessly. His sighs make you flinch as you await further reprimand.

He pulls in before a shop front of white trimmed in red. He gets out without waiting and you follow after him. You trail him inside as he strolls across to the counter where women in red aprons and caps smile back at him.

“Hello, I’ve come to pick up an order for Odinson,” he declares flatly.

“Frigga? Oh yes,” the shorter of the pair flits into the backroom.

“You don’t remember me?” The other woman asks. Laufeyson’s eyes shoot darts at her and his brows arch.

“I recall you spilled vodka on my wedding shoes, yes,” he scoffs.

“Oh,” she makes a face, “I thought maybe you’d forgotten that part.”

“Mm,” he hums and taps his fingers on the shining countertop.

The other woman returns and slides over a large white box, a red seal stuck along the corner to keep it firmly closed. Laufeyson takes out his wallet, “how much then?”

“Paid for,” the woman proclaims, “all yours.”

“Right,” he slides the box off and pivots smoothly.

You peer back before you scurry ahead of him to the door, opening it as his hands are full. That woman was at his wedding? Did she know Sif? Was it a big event? Did everyone go? You don’t ask any of the questions that flood your head. You’d rather not know.

He balances the box in one hand and reaches into his pocket for his keys, unlocking the trunk. He tucks the box firmly against the emergency kit to keep it in place.

“Whatever it is, it should be kept cool in here,” he shuts the lid, “though I wonder why mother couldn’t have it brought with tomorrow’s delivery.”

You don’t say a word. You wouldn’t know either. He strides back along the side of the car and dips into the driver seat. You mirror him as you get in on the passenger’s and he presses the button to turn the engine. He sighs and rests the heel of his hand on the steering wheel. He glances in the rear view.

“I’ve another stop to make.”

That’s all he says. It isn’t a question, just a statement. Though you wonder why he even made the declaration. You don’t need to know, you just go along.

He backs out and rolls out of the lot into the street. You distract yourself with the other storefronts and the veneers of city buildings. He drives onto an avenue and slows along the curb, shifting to a stop before he once more shuts off the engine.

Again, he gets out without instruction. You follow. That’s all you can do. He heads up to the grey brick house. Where are you? It isn’t until you’re at the front door that you notice the metal placard mounted on the wall; Bragi Skald, Antiques and Artifacts.

Laufeyson clangs the large knocker on the door and checks his watch. You wait. It’s quiet. You see no light through the windows but the curtains are drawn flush to the windows, as if they’ve been sealed.

The hinges whine suddenly as the door swings inward, “Ah, Loki!” A blond man at least head shorter than his visitor greets, “wonderful to see you again. I did have it in my ear that you were about, I was curious as you when you should darken my doorway.”

“Bragi,” Laufeyson replies tersely.

“And who is this gorgeous creature,” the man’s crystal blue eyes surprise you as the bow in his lip deepens. He sends you a wink and offers his hand, “forgive me, sweetheart, I nearly missed you there, and how could I overlook such a ravishing woman.”

“Enough,” Laufeyson girds.

“I haven’t even introduced myself–”

“This is Bragi,” Laufeyson introduces the man then utters your name pointedly in return.

“Ah, beautiful name but that hardly answers my curiosity. Who is she? Oh, don’t tell me, you’re marrying again–”

“Hardly,” Laufeyson swipes away the thought with his hand, “I only need to be away from my family.”

“Yes, yes, of course. With Walpurgisnacht, I can only imagine–”

“Be glad you only have to imagine it,” Laufeyson scowls. “Are you going to welcome us in or shall we continue to stand on your porch like tramps?”

“Come, come,” Bragi opens the door wider, “Lady, please, don’t mind the clutter.”

Laufeyson waves you ahead of him. You enter and hold back your shock at the interior. You can hardly see the walls for the stacks of books all around, many with sheaths of paper jutting out. It smells like cinnamon and hint of dust.

“What are we in the mood for? Tea? Or something stronger? I’ve some absinthe–”

“Don’t be mad,” Laufeyson rebukes, “tea will do fine. Just tea, none of your tricks.”

“You speak to me of tricks?” Bragi hums, “is that a sense of humour I sense, oh, dour Loki.”

You lock your jaw to keep from gaping. You’ve never heard anyone talk to Mr. Laufeyson like that, not anyone outside his family, and even Thor did not mock him so lightly.

“Do you want tea?” Laufeyson looks over at you.

“If it isn’t any trouble.”

“Tea,” Laufeyson snaps his fingers at Bragi.

“Do you like scones, lady?” Bragi turns his attention to you.

“I’m not very hungry, thank you–”

“Lady!” A squawk makes you jump, drawing your attention to the flutter of blue feathers that descends to perch on the banister post. A great blue parrot tweaks its head and repeats the word.

“Oh, hush,” Bragi shoos away the bird but only receives a nip of its sharp beak, “don’t listen to Fossegrim. He talks too much.” Bragi shakes his head and retreats down the hallway, “tea, tea, tea…” he chants as if he might forget.

Laufeyson tuts, “he speaks of talking too much…”

You stare up at the blue parrot as it stares back at you. Around its eyes and mouth are bright yellow strips. It’s a pretty creature.

“Lady,” it bawks again and hops off the banister, winging around the space to land on your shoulder.

You gasp as Laufeyson takes a step back. He just sends a troubled look to the bird and glances around, “in here,” he points you through the doorway behind him.

“Um…” you move carefully, trying not to disturb the bird.

In the next room, a large harp stands in one corner, a piano the other, and a litter of various instruments on shelves mounted on the walls. There’s a twelve-string guitar on the sofa, leaned against the armrest as if it was left there haphazardly.

“Be very careful,” Laufeyson returns, “it bites.”

“Bite!” The parrot squawks and snaps in Mr. Laufeyson’s direction. He sighs and once more eludes the bird’s breadth.

“Wish he’d lock that thing up,” he mutters.

You stand like a statue, nervous. You turn your head slowly to look at the parrot. It leans in and nuzzles your hair. You stay as you are, paralysed as you fear it might snap at you too. A grating chitter rises from its throat, softer than its former screech. It continues the purrlike noise as it rocks on your shoulder.

“Is it singing?” You ask as Laufeyson stares with arms crossed.

“I have no idea. Let’s hope it’s not growling.”

You frown and clasp your hands tight. If the bird keeps Mr. Laufeyson away, it can’t be so bad.

#loki#dark loki#dark!loki#loki x reader#fic#dark fic#dark!fic#dirty work#series#au#maid au#avengers#mcu#marvel#thor

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Hawthorne and His Mosses" by Herman Melville

A papered chamber in a fine old farm-house--a mile from any other dwelling, and dipped to the eaves in foliage--surrounded by mountains, old woods, and Indian ponds,--this, surely is the place to write of Hawthorne. Some charm is in this northern air, for love and duty seem both impelling to the task. A man of a deep and noble nature has seized me in this seclusion. His wild, witch voice rings through me; or, in softer cadences, I seem to hear it in the songs of the hill-side birds, that sing in the larch trees at my window.

Would that all excellent books were foundlings, without father or mother, that so it might be, we could glorify them, without including their ostensible authors. Nor would any true man take exception to this;--least of all, he who writes,--"When the Artist rises high enough to achieve the Beautiful, the symbol by which he makes it perceptible to mortal senses becomes of little value in his eyes, while his spirit possesses itself in the enjoyment of the reality."

But more than this, I know not what would be the right name to put on the title-page of an excellent book, but this I feel, that the names of all fine authors are fictitious ones, far more than that of Junius,--simply standing, as they do, for the mystical, ever-eluding Spirit of all Beauty, which ubiquitously possesses men of genius. Purely imaginative as this fancy may appear, it nevertheless seems to receive some warranty from the fact, that on a personal interview no great author has ever come up to the idea of his reader. But that dust of which our bodies are composed, how can it fitly express the nobler intelligences among us? With reverence be it spoken, that not even in the case of one deemed more than man, not even in our Saviour, did his visible frame betoken anything of the augustness of the nature within. Else, how could those Jewish eyewitnesses fail to see heaven in his glance.

It is curious, how a man may travel along a country road, and yet miss the grandest, or sweetest of prospects, by reason of an intervening hedge, so like all other hedges, as in no way to hint of the wide landscape beyond. So has it been with me concerning the enchanting landscape in the soul of this Hawthorne, this most excellent Man of Mosses. His "Old Manse" has been written now four years, but I never read it till a day or two since. I had seen it in the book-stores--heard of it often--even had it recommended to me by a tasteful friend, as a rare, quiet book, perhaps too deserving of popularity to be popular. But there are so many books called "excellent," and so much unpopular merit, that amid the thick stir of other things, the hint of my tasteful friend was disregarded; and for four years the Mosses on the Old Manse never refreshed me with their perennial green. It may be, however, that all this while, the book, like wine, was only improving in flavor and body. At any rate, it so chanced that this long procrastination eventuated in a happy result. At breakfast the other day, a mountain girl, a cousin of mine, who for the last two weeks has every morning helped me to strawberries and raspberries,--which like the roses and pearls in the fairy-tale, seemed to fall into the saucer from those strawberry-beds her cheeks,--this delightful crature, this charming Cherry says to me--"I see you spend your mornings in the hay-mow; and yesterday I found there 'Dwight's Travels in New England'. Now I have something far better than that,--something more congenial to our summer on these hills. Take these raspberries, and then I will give you some moss."--"Moss!" said I--"Yes, and you must take it to the barn with you, and good-bye to 'Dwight.'"

With that she left me, and soon returned with a volume, verdantly bound, and garnished with a curious frontispiece in green,--nothing less, than a fragment of real moss cunningly pressed to a fly-leaf.--"Why this," said I, spilling my raspberries, "this is the 'Mosses from an Old Manse'." "Yes," said cousin Cherry, "yes, it is that flowery Hawthorne."--"Hawthorne and Mosses," said I, "no more: it is morning: it is July in the country: and I am off for the barn."

Stretched on that new mown clover, the hill-side breeze blowing over me through the wide barn door, and soothed by the hum of the bees in the meadows around, how magically stole over me this Mossy Man! And how amply, how bountifully, did he redeem that delicious promise to his guests in the Old Manse, of whom it is written--"Others could give them pleasure, or amusement, or instruction--these could be picked up anywhere--but it was for me to give them rest. Rest, in a life of trouble! What better could be done for weary and world-worn spirits? what better could be done for anybody, who came within our magic circle, than to throw the spell of a magic spirit over them?"--So all that day, half-buried in the new clover, I watched this Hawthorne's "Assyrian dawn, and Paphian sunset and moonrise, from the summit of our Eastern Hill."

The soft ravishments of the man spun me round in a web of dreams, and when the book was closed, when the spell was over, this wizard "dismissed me with but misty reminiscences, as if I had been dreaming of him."

What a mild moonlight of contemplative humor bathes that Old Manse!--the rich and rare distilment of a spicy and slowly-oozing heart. No rollicking rudeness, no gross fun fed on fat dinners, and bred in the lees of wine,--but a humor so spiritually gentle, so high, so deep, and yet so richly relishable, that it were hardly inappropriate in an angel. It is the very religion of mirth; for nothing so human but it may be advanced to that. The orchard of the Old Manse seems the visible type of the fine mind that has described it. Those twisted, and contorted old trees, "that stretch out their crooked branches, and take such hold of the imagination, that we remember them as humorists and odd-fellows." And then, as surrounded by these grotesque forms, and hushed in the noon-day repose of this Hawthorne's spell, how aptly might the still fall of his ruddy thoughts into your soul be symbolized by "the thump of a great apple, in the stillest afternoon, falling without a breath of wind, from the mere necessity of perfect ripeness"! For no less ripe than ruddy are the apples of the thoughts and fancies in this sweet Man of Mosses.

"Buds and Bird-Voices"--What a delicious thing is that!--"Will the world ever be so decayed, that Spring may not renew its greeness?"--And the "Fire-Worship." Was ever the hearth so glorified into an altar before? The mere title of that piece is better than any common work in fifty folio volumes. How exquisite is this:--"Nor did it lessen the charm of his soft, familiar courtesy and helpfulness, that the mighty spirit, were opportunity offered him, would run riot through the peaceful house, wrap its inmates in his terrible embrace, and leave nothing of them save their whitened bones. This possibility of mad destruction only made his domestic kindness the more beautiful and touching. It was so sweet of him, being endowed with such power, to dwell, day after day, and one long, lonesome night after another, on the dusky hearth, only now and then betraying his wild nature, by thrusting his red tongue out of the chimney-top! True, he had done much mischief in the world, and was pretty certain to do more, but his warm heart atoned for all. He was kindly to the race of man."

But he has still other apples, not quite so ruddy, though full as ripe:--apples, that have been left to wither on the tree, after the pleasant autumn gathering is past. The sketch of "The Old Apple Dealer" is conceived in the subtlest spirit of sadness; he whose "subdued and nerveless boyhood prefigured his abortive prime, which, likewise, contained within itself the prophecy and image of his lean and torpid age." Such touches as are in this piece can not proceed from any common heart. They argue such a depth of tenderness, such a boundless sympathy with all forms of being, such an omnipresent love, that we must needs say, that this Hawthorne is here almost alone in his generation,--at least, in the artistic manisfestation of these things. Still more. Such touches as these,--and many, very many similar ones, all through his chapters--furnish clews, whereby we enter a little way into the intricate, profound heart where they originated. And we see, that suffering, some time or other and in some shape or other,--this only can enable any man to depict it in others. All over him, Hawthorne's melancholy rests like an Indian summer, which, though bathing a whole country in one softness, still reveals the distinctive hue of every towering hill, and each far-winding vale.

But it is the least part of genius that attracts admiration. Where Hawthorne is known, he seems to be deemed a pleasant writer, with a pleasant style,--a sequestered, harmless man, from whom any deep and weighty thing would hardly be anticipated:--a man who means no meanings. But there is no man, in whom humor and love, like mountain peaks, soar to such a rapt height, as to receive the irradiations of the upper skies;--there is no man in whom humor and love are developed in that high form called genius; no such man can exist without also possessing, as the indispensable complement of these, a great, deep intellect, which drops down into the universe like a plummet. Or, love and humor are only the eyes, through which such an intellect views this world. The great beauty in such a mind is but the product of its strength. What, to all readers, can be more charming than the piece entitled "Monsieur du Miroir"; and to a reader at all capable of fully fathoming it, what at the same time, can possess more mystical depth of meaning?--Yes, there he sits, and looks at me,--this "shape of mystery," this "identical Monsieur du Miroir."--"Methinks I should tremble now, were his wizard power of gliding through all impediments in search of me, to place him suddenly before my eyes."

How profound, nay appalling, is the moral evolved by the "Earth's Holocaust"; where--beginning with the hollow follies and affectations of the world,--all vanities and empty theories and forms, are, one after another, and by an admirably graduated, growing comprehensiveness, thrown into the allegorical fire, till, at length, nothing is left but the all-engendering heart of man; which remaining still unconsumed, the great conflagration is naught.

Of a piece with this, is the "Intelligence Office," a wondrous symbolizing of the secret workings in men's souls. There are other sketches, still more charged with ponderous import.

"The Christmas Banquet," and "The Bosom Serpent" would be fine subjects for a curious and elaborate analysis, touching the conjectural parts of the mind that produced them. For spite of all the Indian-summer sunlight on the hither side of Hawthorne's soul, the other side--like the dark half of the physical sphere--is shrouded in a blackness, ten times black. But this darkness but gives more effect to the evermoving dawn, that forever advances through it, and cirumnavigates his world. Whether Hawthorne has simply availed himself of this mystical blackness as a means to the wondrous effects he makes it to produce in his lights and shades; or whether there really lurks in him, perhaps unknown to himself, a touch of Puritanic gloom,--this, I cannot altogether tell. Certain it is, however, that this grat power of blackness in him derives its force from its appeals to that Calvinistic sense of Innate Depravity and Original Sin, from whose visitations, in some shape or other, no deeply thinking mind is always and wholly free. For, in certain moods, no man can weigh this world, without throwing in something, somehow like Original Sin, to strike the uneven balance. At all events, perhaps no writer has ever wielded this terrific thought with greater terror than this same harmless Hawthorne. Still more: this black conceit pervades him, through and through. You may be witched by his sunlight,--transported by the bright gildings in the skies he builds over you;--but there is the blackness of darkness beyond; and even his bright gildings but fringe, and play upon the edges of thunder-clouds.--In one word, the world is mistaken in this Nathaniel Hawthorne. He himself must often have smiled at its absurd misconceptions of him. He is immeasurably deeper than the plummet of the mere critic. For it is not the brain that can test such a man; it is only the heart. You cannot come to know greatness by inspecting it; there is no glimpse to be caught of it, except by intuition; you need not ring it, you but touch it, and you find it is gold.

Now it is that blackness in Hawthorne, of which I have spoken, that so fixes and fascinates me. It may be, nevertheless, that it is too largely developed in him. Perhaps he does not give us a ray of his light for every shade of his dark. But however this may be, this blackness it is that furnishes the infinite obscure of his background,--that background, against which Shakespeare plays his grandest conceits, the things that have made for Shakespeare his loftiest, but most circumscribed renown, as the profoundest of thinkers. For by philosophers Shakespeare is not adored as the great man of tragedy and comedy.--"Off with his head! so much for Buckingham!" this sort of rant, interlined by another hand, brings down the house,--those mistaken souls, who dream of Shakespeare as a mere man of Richard-the-Third humps, and Macbeth daggers. But it is those deep far-away things in him; those occasional flashings-forth of the intuitive Truth in him; those short, quick probings at the very axis of reality:--these are the things that make Shakespeare, Shakespeare. Through the mouths of the dark characters of Hamlet, Timon, Lear, and Iago, he craftily says, or sometimes insinuates the things, which we feel to be so terrifically true, that it were all but madness for any good man, in his own proper character, to utter, or even hint of them. Tormented into desperation, Lear the frantic King tears off the mask, and speaks the sane madness of vital truth. But, as I before said, it is the least part of genius that attracts admiration. And so, much of the blind, unbridled admiration that has been heaped upon Shakespeare, has been lavished upon the least part of him. And few of his endless commentators and critics seem to have remembered, or even perceived, that the immediate products of a great mind are not so great, as that undeveloped, (and sometimes undevelopable) yet dimly-discernible greatness, to which these immediate products are but the infallible indices. In Shakespeare's tomb lies infinitely more than Shakespeare ever wrote. And if I magnify Shakespeare, it is not so much for what he did do, as for what he did not do, or refrained from doing. For in this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a scared white doe in the woodlands; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself, as in Shakespeare and other masters of the great Art of Telling the Truth,--even though it be covertly, and by snatches.

But if this view of the all-popular Shakespeare be seldom taken by his readers, and if very few who extol him, have ever read him deeply, or, perhaps, only have seen him on the tricky stage, (which alone made, and is still making him his mere mob renown)--if few men have time, or patience, or palate, for the spiritual truth as it is in that great genius;--it is, then, no matter of surprise that in a contemporaneous age, Nathaniel Hawthorne is a man, as yet, almost utterly mistaken among men. Here and there, in some quiet arm-chair in the noisy town, or some deep nook among the noiseless mountains, he may be appreciated for something of what he is. But unlike Shakespeare, who was forced to the contrary course by circumstances, Hawthorne (either from simple disinclination, or else from inaptitude) refrains from all the popularizing noise and show of broad farce, and blood-besmeared tragedy; content with the still, rich utterances of a great intellect in repose, and which sends few thoughts into circulation, except they be arterialized at his large warm lungs, and expanded in his honest heart.

Nor need you fix upon that blackness in him, if it suit you not. Nor, indeed, will all readers discern it, for it is, mostly, insinuated to those who may best undersand it, and account for it; it is not obtruded upon every one alike.

Some may start to read of Shakespeare and Hawthorne on the same page. They may say, that if an illustration were needed, a lesser light might have sufficed to elucidate this Hawthorne, this small man of yesterday. But I am not, willingly, one of those, who as touching Shakespeare at least, exemplify the maxim of Rochefoucauld, that "we exalt the reputation of some, in order to depress that of others";--who, to teach all noble-souled aspirants that there is no hope for them, pronounce Shakespeare absolutely unapproachable. But Shakespeare has been approached. There are minds that have gone as far as Shakespeare into the universe. And hardly a mortal man, who, at some time or other, has not felt as great thoughts in him as any you will find in Hamlet. We must not inferentially malign mankind for the sake of any one man, whoever he may be. This is too cheap a purchase of contentment for consious mediocrity to make. Besides, this absolute and unconditional adoration of Shakespeare has grown to be a part of our Anglo Saxon superstitions. The Thirty-Nine Articles are now Forty. Intolerance has come to exist in this matter. You must believe in Shakespeare's unapproachability, or quit the country. But what sort of belief is this for an American, an man who is bound to carry republican progressiveness into Literature, as well as into Life? Believe me, my friends, that men not very much inferior to Shakespeare, are this day being born on the banks of the Ohio. And the day will come, when you shall say who reads a book by an Englishman that is a modern? The great mistake seems to be, that even with those Americans who look forward to the coming of a great literary genius among us, they somehow fancy he will come in the costume of Queen Elizabeth's day,--be a writer of dramas founded upon old English history, or the tales of Boccaccio. Whereas, great geniuses are parts of the times; they themselves are the time; and possess an correspondent coloring. It is of a piece with the Jews, who while their Shiloh was meekly walking in their streets, were still praying for his magnificent coming; looking for him in a chariot, who was already among them on an ass. Nor must we forget, that, in his own life-time, Shakespeare was not Shakespeare, but only Master William Shakespeare of the shrewd, thriving business firm of Condell, Shakespeare & Co., proprietors of the Globe Theater in London; and by a courtly author, of the name of Chettle, was hooted at, as an "upstart crow" beautfied "with other birds' feathers." For, mark it well, imitation is often the first charge brought against real originality. Why this is so, there is not space to set forth here. You must have plenty of sea-room to tell the Truth in; especially, when it seems to have an aspect of newness, as American did in 1492, though it was then just as old, and perhaps older than Asia, only those sagacious philosophers, the common sailors, had never seen it before; swearing it was all water and moonshine there.

Now, I do not say that Nathaniel of Salem is a greater than William of Avon, or as great. But the difference between the two men is by no means immeasurable. Not a very great deal more, and Nathaniel were verily William.

This too, I mean, that if Shakespeare has not been equalled, give the world time, and he is sure to be surpassed, in one hemisphere or the other. Nor will it at all do to say, that the world is getting grey and grizzled now, and has lost that fresh charm which she wore of old, and by virtue of which the great poets of past times made themselves what we esteem them to be. Not so. the world is as young today, as when it was created, and this Vermont morning dew is as wet to my feet, as Eden's dew to Adam's. Nor has Nature been all over ransacked by our progenitors, so that no new charms and mysteries remain for this latter generation to find. Far from it. The trillionth part has not yet been said, and all that has been said, but multiplies the avenues to what remains to be said. It is not so much paucity, as superabundance of material that seems to incapacitate modern authors.

Let American then prize and cherish her writers, yea, let her glorify them. They are not so many in number, as to exhaust her good-will. And while she has good kith and kin of her own, to take to her bosom, let her not lavish her embraces upon the household of an alien. For believe it or not England, after all, is, in many things, an alien to us. China has more bowels of real love for us than she. But even were there no strong literary individualities among us, as there are some dozen at least, nevertheless, let America first praise mediocrity even, in her own children, before she praises (for everywhere, merit demands acknowledgment from every one) the best excellence in the children of any other land. Let her own authors, I say, have the priority of appreciation. I was very much pleased with a hot-headed Carolina cousin of mine, who once said,--"If there were no other American to stand by, in Literature,--why, then, I would stand by Pop Emmons and his 'Fredoniad,' and till a better epic came along, swear it was not very far behind the 'Iliad'." Take away the words, and in spirit he was sound.

Not that American genius needs patronage in order to expand. For that explosive sort of stuff will expand though screwed up in a vice, and burst it, though it were triple steel. It is for the nation's sake, and not for her authors' sake, that I would have America be heedful of the increasing greatness among her writers. For how great the shame, if other nations should be before her, in crowning her heroes of the pen. But this is almost the case now. American authors have received more just and discriminating praise (however loftily and ridiculously given, in certain cases) even from some Englishmen, than from their own countrymen. There are hardly five critics in America, and several of them are asleep. As for patronage, it is the American author who now patronizes the country, and not his country him. And if at times some among them appeal to the people for more recognition, it is not always with selfish motives, but patriotic ones.

It is true, that but few of them as yet have evinced that decided originality which merits great praise. But that graceful writer, who perhaps of all Americans has received the most plaudits from his own country for his productions,--that very popular and amiable writer, however good, and self-reliant in many things, perhaps owes his chief reputation to the self-acknowledged imitation of a foreign model, and to the studied avoidance of all topics but smooth ones. But it is better to fail in originality, than to succeed in imitation. He who has never failed somewhere, that man can not be great. Failure is the true test of greatness. And if it be said, that continual success is a proof that a man wisely knows his powers,--it is only to be added, that, in that case, he knows them to be small. Let us believe it, then, once for all, that there is no hope for us in these smooth pleasing writers that know their powers. Without malice, but to speak the plain fact, they but furnish an appendix to Goldsmith, and other English authors. And we want no American Goldsmiths, nay, we want no American Miltons. It were the vilest thing you could say of a true American author, that he were an American Tompkins. Call him an American, and have done, for you can not say a nobler thing of him.--But it is not meant that all American writers should studiously cleave to nationality in their writings; only this, no American writer should write like an Englishman, or a Frenchman; let him write like a man, for then he will be sure to write like an American. Let us away with this leaven of literary flunkyism towards England. If either we must play the flunky in this thing, let England do it, not us. While we are rapidly preparing for that political supremacy among the nations, which prophetically awaits us at the close of the present century; in a literary point of view, we are deplorably unprepared for it; and we seem studious to remain so. Hitherto, reasons might have existed why this should be; but no good reason exists now. And all that is requisite to amendment in this matter, is simply this: that, while freely acknowledging all excellence, everywhere, we should refrain from unduly lauding foreign writers, and, at the same time, duly recognize the meritorious writers that are our own,--those writers, who breathe that unshackled, democratic spirit of Christianity in all things, which now takes the practical lead in the world, though at the same time led by ourselves--us Americans. Let us boldly contemn all imitation, though it comes to us graceful and fragrant as the morning; and foster all originality, though, at first, it be crabbed and ugly as our own pine knots. And if any of our authors fail, or seem to fail, then, in the words of my enthusiastic Carolina cousin, let us clap him on the shoulder, and back him against all Europe for his second round. The truth is, that in our point of view, this matter of a national literature has come to such a pass with us, that in some sense we must turn bullies, else the day is lost, or superiority so far beyond us, that we can hardly say it will ever be ours.

And now, my countrymen, as an excellent author, of your own flesh and blood,--an unimitating, and perhaps, in his way, an inimitable man--whom better can I commend to you, in the first place, than Nathaniel Hawthorne. He is one of the new, and far better generation of your writer. The smell of your beeches and hemlocks is upon him; your own broad prairies are in his soul; and if you travel away inland into his deep and noble nature, you will hear the far roar of his Niagara. Give not over to future generations the glad duty of acknowledging him for what he is. Take that joy to yourself, in your own generation; and so shall he feel those grateful impulses in him, that may possibly prompt him to the full flower of some still greater achievement in your eyes. And by confessing him, you thereby confess others, you brace the whole brotherhood. For genius, all over the world, stands hand in hand, and one shock of recognition runs the whole circle round.

In treating of Hawthorne, or rather of Hawthorne in his writings (for I never saw the man; and in the chances of a quiet plantation life, remote from his haunts, perhaps never shall) in treating of his works, I say, I have thus far omitted all mention of his "Twice Told Tales," and "Scarlet Letter." Both are excellent, but full of such manifold, strange and diffusive beauties, that time would all but fail me, to point the half of them out. But there are things in those two books, which, had they been written in England a century ago, Nathaniel Hawthorne had utterly displaced many of the bright names we now revere on authority. But I content to leave Hawthorne to himself, and to the infallible finding of posterity; and however great may be the praise I have bestowed upon him, I feel, that in so doing, I have more served and honored myself, than him. For at bottom, great excellence is praise enough to itself; but the feeling of a sincere and appreciative love and admiration towards it, this is relieved by utterance; and warm, honest praise ever leaves a pleasant flavor in the mouth; and it is an honorable thing to confess to what is honorable in others.

But I cannot leave my subject yet. No man can read a fine author, and relish him to his very bones, while he reads, without subsequently fancying to himself some ideal image of the man and his mind. And if you rightly look for it, you will almost always find that the author himself has somewhere furnished you with his own picture. For poets (whether in prose or verse), being painters of Nature, are like their brethren of the pencil, the true portrait-painters, who, in the multitude of likenesses to be sketched, do not invariably omit their own; and in all high instances, they paint them without any vanity, though, at times, with a lurking something, that would take several pages to properly define.

I submit it, then, to those best acquainted with the man personally, whether the following is not Nathaniel Hawthorne,--to to himself, whether something involved in it does not express the temper of this mind,--that lasting temper of all true, candid men--a seeker, not a finder yet:--

A man now entered, in neglected attire, with the aspect of a thinker, but somewhat too rough-hewn and brawny for a scholar. His face was full of sturdy vigor, with some finer and keener attribute beneath; though harsh at first, it was tempered with the glow of a large, warm heart, which had force enough to heat his powerful intellect through and through. He advanced to the Intelligencer, and looked at him with a glance of such stern sincerity, that perhaps few secrets were beyond its scope.

"'I seek for Truth,' said he."

Twenty-four hours have elapsed since writing the foregoing. I have just returned from the hay mow, charged more and more with love and admiration of Hawthorne. For I have just been gleaning through the "Mosses," picking up many things here and there that had previously escaped me. And I found that but to glean after this man, is better than to be in at the harvest of others. To be frank (though, perhaps, rather foolish), notwithstanding what I wrote yesterday of these Mosses, I had not then culled them all; but had, nevertheless, been sufficiently sensible of the subtle essence, in them, as to write as I did. to what infinite height of loving wonder and admiration I may yet be borne, when by repeatedly banquetting on these Mosses, I shall have thoroughly incorporated their whole stuff into my being,--that, I can not tell. But already I feel that this Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul. He expands and deepens down, the more I contemplate him; and further, and further, shoots his strong New-England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul.

By careful reference to the "Table of Contents," I now find, that I have gone through all the sketches; but that when I yeterday wrote, I had not at all read two particular pieces, to which I now desire to call special attention,--"A Select Party," and "Young Goodman Brown." Here, be it said to all those whom this poor fugitive scrawl of mine may tempt to the purusal of the "Mosses," that they must on no account suffer themselves to be trifled with, disappointed, or deceived by the triviality of many of the titles to these Sketches. For in more than one instance, the title utterly belies the piece. It is as if rustic demjohns containing the very best and costliest of Falernian and Tokay, were labeled "Cider," "Perry," and "Elder-berry Wine." The truth seems to be, that like many other geniuses, this Man of Mosses takes great delight in hoodwinking the world,--at least, with respect to himself. Personally, I doubt not, that he rather prefers to be generally esteemed but a so-so sort of author; being willing to reserve the thorough and acute appreciation of what he is, to that party most qualified to judge--that is, to himself. Besides, at the bottom of their natures, men like Hawthorne, in many things, deem the plaudits of the public such strong presumptive evidence of mediocrity in the object of them, that it would in some degree render them doubtful of their own powers, did they hear much and vociferous braying concerning them in the public pastures. True, I have been braying myself (if you please to be witty enough, to have it so) but then I claim to be the first that has so brayed in this particular matter; and therefore, while pleading guilty to the charge, still claim all the merit due to originality.

But with whatever motive, playful or profound, Nathaniel Hawthorne has chosen to entitle his pieces in the manner he has, it is certain, that some of them are directly calculated to deceive--egregiously deceive--the superficial skimmer of pages. To be downright and candid once more, let me cheerfully say, that two of these titles did dolefully dupe no less an eagle-eyed reader than myself, and that, too, after I had been impressed with a sense of the great depth and breadth of this American man. "Who in the name of thunder," (as the country-people say in this neighborhood), "who in the name of thunder, would anticipate any marvel in a piece entitled "Young Goodman Brown"? You would of course suppose that it was a simple little tale, intended as a supplement to "Goody Two Shoes." Whereas, it is deep as Dante; nor can you finish it, without addressing the author in his own words--"It is yours to penetrate, in every bosom, the deep mystery of sin." And with Young Goodman, too, in allegorical pursuit of his Puritan wife, you cry out in your anguish,--

"Faith!" shouted Goodman Brown, in a voice of agony and desperation; and the echoes of the forest mocked him, crying--"Faith! Faith!" as if bewildered wretches were seeking her all through the wilderness.

Now this same piece, entitled "Young Goodman Brown," is one of the two that I had not all read yesterday; and I allude to it now, because it is, in itself, such a strong positive illustration of that blackness in Hawthorne, which I had assumed from the mere occasional shadows of it, as revealed in several of the other sketches. But had I previously perused "Young Goodman Brown," I should have been at no pains to draw the conclusion, which I came to, at a time, when I was ignorant that the book contained one such direct and unqualified manifestation of it.

The other piece of the two referred to, is entitled "A Select Party," which in my first simplicity upon originally taking hold of the book, I fancied must treat of some pumpkin-pie party in Old Salem, or some Chowder Party on Cape Cod. Whereas, by all the gods of Peedee! it is the sweetest and sublimest thing that has been written since Spenser wrote. Nay, there is nothing in Spenser that surpasses it, perhaps, nothing that equals it. And the test is this: read any canto in "The Faery Queen," and then read "A Select Party," and decide which pleases you the most,--that is, if you are qualified to judge. Do not be frightened at this; for when Spenser was alive, he was thought of very much as Hawthorne is now--was generally accounted just such a "gentle" harmless man. It may be, that to common eyes, the sublimity of Hawthorne seems lost in his sweetness,--as perhaps in this same "Select Party" his; for whom, he has builded so august a dome of sunset clouds, and served them on richer plate, than Belshazzar's when he banquetted his lords in Babylon.

But my chief business now, is to point out a particular page in this piece, having reference to an honored guest, who under the name of "The Master Genius" but in the guise "of a young man of poor attire, with no insignia of rank or acknowledged eminence," is introduced to the Man of Fancy, who is the giver of the feast. Now the page having reference to this "Master Genius", so happily expresses much of what I yesterday wrote, touching the coming of the literary Shiloh of America, that I cannot but be charmed by the coincidence; especially, when it shows such a parity of ideas, at least, in this one point, between a man like Hawthorne and a man like me.

And here, let me throw out another conceit of mine touching this American Shiloh, or "Master Genius," as Hawthorne calls him. May it not be, that this commanding mind has not been, is not, and never will be, individually developed in any one man? And would it, indeed, appear so unreasonable to suppose, that this great fullness and overlowing may be, or may be destined to be, shared by a plurality of men of genius? Surely, to take the very greatest example on record, Shakespeare cannot be regarded as in himself the concretion of all the genius of his time; nor as so immeasurably beyond Marlowe, Webster, Ford, Beaumont, Johnson, that those great men can be said to share none of his power? For one, I conceive that there were dramatists in Elizabeth's day, between whom and Shakespeare the distance was by no means great. Let anyone, hitherto little acquainted with those neglected old authors, for the first time read them thoroughly, or even read Charles Lamb's Specimens of them, and he will be amazed at the wondrous ability of those Anaks of men, and shocked at this renewed example of the fact, that Fortune has more to do with fame than merit,--though, without merit, lasting fame there can be none.

Nevertheless, it would argue too illy of my country were this maxim to hold good concerning Nathaniel Hawthorne, a man, who already, in some minds, has shed "such a light, as never illuminates the earth, save when a great heart burns as the household fire of a grand intellect."

The words are his,--in the "Select Party"; and they are a magnificent setting to a coincident sentiment of my own, but ramblingly expressed yesterday, in reference ot himself. Gainsay it who will, as I now write, I am Posterity speaking by proxy--and after times will make it more than good, when I declare--that the American, who up to the present day, has evinced, in Literature, the largest brain with the largest heart, that man is Nathaniel Hawthorne. Moreover, that whatever Nathaniel Hawthorne may hereafter write, "The Mosses from an Old Manse" will be ultimately accounted his masterpiece. For there is a sure, though a secret sign in some works which proves the culmination of the power (only the developable ones, however) that produced them. But I am by no means desirous of the glory of a prophet. I pray Heaven that Hawthorne may yet prove me an impostor in this prediciton. Especially, as I somehow cling to the strange fancy, that, in all men, hiddenly reside certain wondrous, occult properties--as in some plants and minerals--which by some happy but very rare accident (as bronze was discovered by the melting of the iron and brass in the burning of Corinth) may chance to be called forth here on earth, not entirely waiting for their better discovery in the more congenial, blessed atmosphere of heaven.

Once more--for it is hard to be finite upon an infinite subject, and all subjects are infinite. By some people, this entire scrawl of mine may be esteemed altogether unnecessary, inasmuch, "as years ago" (they may say) "we found out the rich and rare stuff in this Hawthorne, whom you now parade forth, as if only yourself were the discoverer of this Portuguese diamond in our Literature."--But even granting all this; and adding to it, the assumption that the books of Hawthorne have sold by the five-thousand,--what does that signify?--They should be sold by the hundred-thousand, and read by the million; and admired by every one who is capable of Admiration.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I Read in 2024, #8: Moby Dick (Herman Melville, Independent Publisher (originally Harper & Brothers), 1851)

A sprawling narrative of the narrator Ishmael's time on the whaling ship Pequod, Moby Dick is the story of Captain Ahab's obsessive quest for revenge upon the whale that maimed him. Drawing upon elements of contemporary naturalist writing of the world and whaling, Ishmael paints a sharp picture of the whaling culture and industry of the time and it's foibles and the world it brought into being.

You'll be able to tell eventually based on my to read list, but Limbus Company is partly to blame for my reading this one. I'd long thought about going back to classics, and have done so plenty in the past, but the game by one of my favorite developers drawing upon 12 different classics of literature from across the world was a pretty good reason go step it up a bit more.

And in fact, this one was meant to be posted before Wuthering Heights, but I got swept up in how good that book was and posted it first right after finishing it. Which is not to say that this isn't good. Moby Dick is a fucking banger. Truly crazy. May have given me some grist to work with in some other projects, even.

Moby Dick is a sprawling bastard of a novel, at times lapsing into stage direction, epistolary and direct address of the audience by Ishmael, our near-silent and yet deeply wordy narrator. It feels like the production of a hyperfixation (which on some level it is) and a genuine love for the material, a piece of rock carefully sculpted around a vein of gold that gives you glimpses of what lies underneath without simply laying it all bare. Moby Dick is a novel of small, momentous moments.

Famously, Herman Melville made significant changes to the novel after speaking with Nathaniel Hawthorne (author of Mosses from an Old Manse) to deepen it and draw in elements of human nature, more directly drawing a parallel between Ahab and Moby Dick as a war between Man and God. It's probably felt the strongest in the beginning and the end, when faith and circumstance are both questioned the most. Ishmael is warned against the black end that is coming for the Pequod by Elijah but cannot begin to fathom the reason why, but by the time they arrive in the seas of Japan to hunt Moby Dick, Ahab has forged a harpoon quenched in blood in the name of Satan to slay his foe.

Much of the body of the novel is an exhaustive, frankly beautiful description of the circumstances of whaling, oceangoing and the process of whaling across the world. It would be a mistake to say that this is not necessary to the narrative, though I can imagine so many teens being forced to read this in high school english finding the task tedious in the extreme. And yet, it informs the story directly. Without these things, you would not come to an understanding of Ishmael himself, though it would seem superfluous. It's a labor of utmost love for the people who do this frankly insane and borderline suicidal thing, something that was considered necessary for the time by society at large and represented unerringly in its brutality and horror.

And yet, the novel understands that the pervasive whaling is on some level evil. Moby Dick is a punishment by God himself, a brilliant white avenger of humanity's evil. It strikes like the wrath of god when other whalers engage in the act against other shoals, utterly devastating and driving off the virtuous and sinful in equal measure. The other boats that encounter Moby Dick all survive because they fear it, the representative of God upon the ocean. Only Ahab's singular obsession drives him to ruin, even in the face of being offered the opportunity to repent in the form of the Rachel, the opportunity to turn away from ruin in the pursuit of saving a human life imperiled before them.

The fault lied within you all along, Ahab.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Christmas Banquet" -- Nathaniel Hawthorne

“The Christmas Banquet” by Nathaniel Hawthorne from Mosses from an Old Manse In a certain old gentleman’s last will and testament there appeared a bequest, which, as his final thought and deed, was singularly in keeping with a long life of melancholy eccentricity. He devised a considerable sum for establishing a fund, the interest of which was to be expended, annually forever, in preparing a…

1 note

·

View note

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Mosses From An Old Manse Nathaniel Hawthorne Antiquarian HB Book.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 23: Revolutions on a Rainy Day

Welcome back to my Totally Lit Road Trip blog, where the lit stands for literary!

Today was our second full day in Concord, MA, and despite the steadily increasing rain, we managed to pack in a ton of literary sightseeing.

Our first stop was The Old Manse, a residence where both Ralph Waldo Emerson (who preferred to go by Waldo) and Nathanial Hawthorne lived at some point in their lives. Our tour guide was so knowledgeable and since it was just me and Jess on this tour, it was like having a private guide all to ourselves again.

The first thing our guide stressed was that historians see The Old Manse as the birthplace of two different revolutions - The American Revolution, and the Cultural Revolution of Transcendentalism. The home was built in 1769 by Rev. William Emerson (Waldo’s grandfather), who was the minister of Concord. He married the former minister’s daughter, Phebe Bliss. Known as the “Patriot Preacher,” Rev. Emerson was heavily into politics and supported the revolution, making him very popular with his congregation.

From the window of one of the upstairs bedrooms that would later become Waldo’s bedroom/study, Phebe Emerson and her five children, one of whom would become Waldo’s father, could see the literal beginning of the American Revolution - the first shots fired at the North Bridge. Years later, Waldo would coin the term “the shot heard round the world” in his 1837 poem “Concord Hymn,” which commemorated the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Waldo’s first career path was that of a preacher, however, after the death of his first wife Ellen after only 18 months of marriage, Waldo felt he no longer had the calling of being a minister. Instead, he traveled around Europe for almost a year, meeting other leading authors of the time period, and beginning to shape his philosophies. From this point on, most of his income came from writing and speaking engagements.

After the death of his grandfather, Waldo’s grandmother Phebe remarried, and it was years later when Waldo moved back to the house as an adult to care for his aging step-grandfather. During this time, he wrote “Nature,” the speech considered to be a founding text of the Transcendentalism movement.

Waldo was actually the person who suggested that Nathanial Hawthorne and his wife Sophia be taken on as renters of the home, and Hawthorne is the one who gave it the name “Old Manse”, manse being the British term for a minister’s home. Hawthorne and his wife, Sophia, lived there for about three years, during which he wrote the stories that would eventually come together to form his first successful book, Mosses from an Old Manse. He insisted on writing in the same room of the house which Waldo used as his study, although he had his desk face the wall because unlike Waldo, Hawthorne found nature to be distracting rather than inspiring. Sophia, and accomplished artist, spent much of her time in the house painting. Unfortunately, her last portrait, which she considered to be her best, is of whereabouts unknown.

The Hawthornes were eventually evicted because they were unable to continue paying their rent, due to a dry spell of both writing and artistic income. But they left their lasting marks on the home: Sophia engraved window panes with her diamond ring, and Nathanial left a hole in the house where he installed a stove in the kitchen. (He took the stove with them when they moved out.)

After this the Hawthornes moved to Salem, MA, where Nathanial would go on to write House of the Seven Gables and The Scarlet Letter, arguably his most famous work of fiction. They later moved back to Concord and lived at The Wayside, which is unfortunately not currently open to the public.

One of my favorite things in the house was a Steinway square grand piano, which is still in playable condition. In fact, the tour guides actually encourage guests to sit down and play a few chords to keep it in good working order! Obviously, I had to give it a go, and I can now say that I’ve played a square grand.

Another cool artifact in the house is a grandfather clock built in Limerick, Ireland, which still keeps accurate time when wound, and which stands in the original position in the house that it has occupied since Waldo’s grandfather purchased it.

The bookcases in the house are all built horizontally, and stacked on top of each other, unlike today’s bookshelves. Our tour guide told us that this is because the Emerson’s highly valued their tomes and wanted to be able to easily lift and slide the bookshelves out the windows in case of a fire.

And finally, I would be remiss if I failed to mention Longfellow, the preserved owl that resides at The Old Manse. Apparently no one know how he came to be in the house, but Nathanial Hawthorne found him in the attic when he moved in. The owl is believed to be from colonial times, meaning it existed before the house was built. Nathanial loved it and wanted it to be a centerpiece for conversation when guests came over, but Sophia was creeped out by it, leading to an unending “game” where she would hide it back up in the attic, and he would bring it down again and put it in a different room of the house.

After our wonderful tour of The Old Manse, we stopped for a quick bit to eat at Main Streets Café, where I had a mac ‘n cheese grilled cheese sandwich. That’s right folks, deep fried mac ‘n cheese wedges on a sandwich with even more delicious, cheesy gooiness. Highly recommend.

With our bellies full, we headed over to Emerson House, the home Emerson lived in with his second wife and four children. Emerson House is massive! There are so many rooms and split-levels and doors that lead who knows where. You could get lost in there without a tour guide, but luckily we had a team of lovely women to lead us through the house both physically and historically.

Unfortunately, you can’t take pictures inside Emerson House, but here’s me standing out front in the rain.

One of the coolest things about Emerson house is that, unlike the other authors’ homes in the areas which are all owned by trusts or preservation societies, Emerson House is still owned by direct descendants of Waldo. They take care of the upkeep and allow the Ralph Waldo Emerson Memorial Association to give tours.

Here are some interesting facts we learned about Emerson and his home, in no particular order:

In July 1872, a fire broke out in the attic of the home. Luckily, no one was injured, and they even managed to get all of the furniture (and more importantly, all of the books!) out in time. (Possible due to easily yeet-able bookshelves?) Due to smoke and water damage, the house was unlivable for a time. Emerson did have the house insured, but the whole town banded together to raise additional funds for restoring the home. Different neighbors also volunteered to keep the family’s belongings safe until the home was livable again. While the house was being reconstructed, Emerson and his daughter traveled to Europe and Egypt, and when they returned, the town had a celebration in their honor, and even closed schools for the day!

Waldo was at least six feet tall, and as such would have to duck in some of the lower hallways of the home. He hung his gardening hat on a peg which only he was tall enough to reach.

The Emersons entertained visitors from all over, and Waldo almost never turned away guests, even unannounced ones. He was very generous if people asked for money, and never let anyone leave without a meal.

As a friend of Waldo, Henry David Thoreau lived in the house for long spans of time on multiple occasions. He typically stayed in the room that was meant to be for Waldo’s brother Charles, who tragically died before his wedding. It took Waldo 10 years to finish the room and eventually make it the master bedroom, but Thoreau stayed there frequently. He was a fan favorite of Emerson’s four children, who could often see him approaching the carriage entrance from their window in the nursery. They loved him because he made good popcorn and told good stories.

Waldo was a great friend to the Alcott family. He allowed Louisa May Alcott to use his library and often gave her book recommendations. Alcott’s first book, Flower Fables, is dedicated to Waldo’s daughter, Ellen. Waldo also lent many pieces of art to Louisa’s sister, the artist May Alcott, including one piece that was a wedding gift! She would make copies of the paintings, a common practice for aspiring artists at the time.

And finally, every single room in Emerson House has at least one bookshelf. That right there is life goals.

Right across the street from Emerson House is the Concord Museum, so that was our next stop. This museum has many interactive exhibits and mainly focuses on Concord’s Revolutionary War history, although it does also have a fair share of local author and artist history, as well.

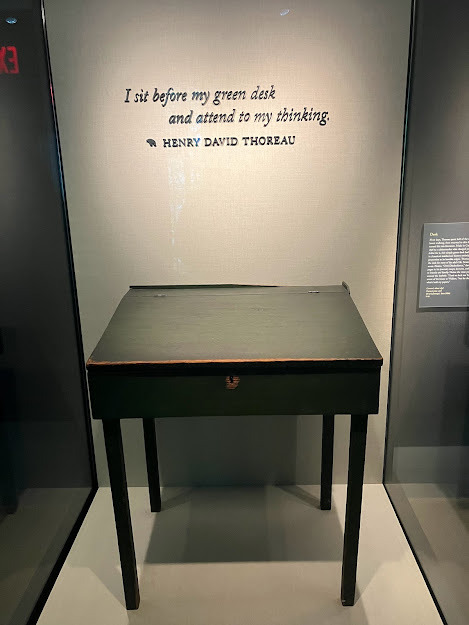

One of the first things you encounter in the museum’s foyer is a replica of Thoreau’s writing desk, which you can sit at and write in a little notebook there.

The original green desk is in one of the galleries as you walk through.

The museum also has many odds and ends from the different local authors. One is Emerson’s writing desk, which was originally green, but then he later painted it black. The replica that resides at The Old Manse is green.

One of Louisa May Alcott’s tea kettles, which she brought with her when she served as a Civil War nurse, is also at the museum.

Also on display is the entirety of Emerson’s study, displayed exactly as they were in his lifetime. Everything in the room is the original!

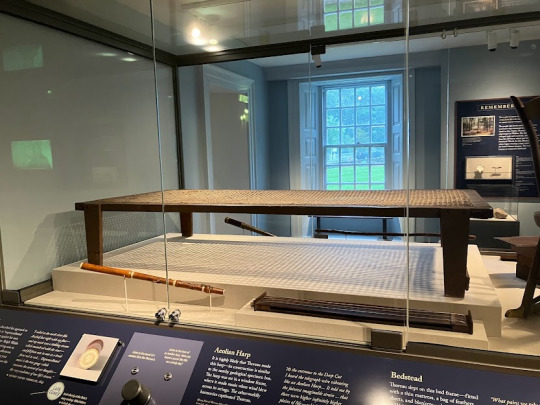

Finally, there is a room dedicated to Thoreau’s belongings, including his bed frame, a wooden flute, and some pencils and surveying tools.

A large portion of the Concord population were abolitionists, and although she was not a native of Concord, the museum does have a first edition of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was originally published in two volumes.

We were lucky enough to be visiting during the Concord Free Public Library’s 150 Years of Art Celebration, so there was a special exhibit with art pieces that are usually at the library. This included busts of Hawthorne, Thoreau, and Alcott, as well as one of May Alcott’s paintings. The largest piece in the library’s collection is a portrait of Emerson, with a rainbow in the background.

After leaving the museum, we browsed for a bit at Concord Bookshop and then drove over to Walden Pond once it finally stopped raining. There, we were able to visit the replica of Thoreau’s writing cabin, which is very small! The original cabin was located on the other side of the pond, but is no longer standing. Visitors who are into hiking can hike up to the point where the cabin once stood and where many admirers leave rocks as a sign that they’ve been there. (Not me and Jessica. We’re indoor people!)

We ended our night with some sushi at Karma (highly recommend the Golden Banana Roll...banana and eel, who knew?!), and ice cream at Bedford Farms, where their “small” is my “large”.

In two and a half days, we managed to squeeze in every literary and historical attraction that we planned for, which is pretty impressive, especially considering the rain. It was definitely made easier by the fact that everything in Concord is so close to each other.

Before we head home tomorrow, we hope to stop by the North Bridge, the site of the beginning of the American Revolution. Hopefully the rain will hold up long enough to let us walk to the bridge and see Daniel Chester French’s Minute Man statue.

Stay tuned for more literary/historical adventures!

<3 Theresa

#totallylitroadtrips#totally lit road trips#totallylitroadtrip#totally lit road trip#concord#massachusetts#the old manse#emerson house#concord museum#ralph waldo emerson#nathaniel hawthorne#louisa may alcott#henry david thoreau#walden pond

1 note

·

View note

Text

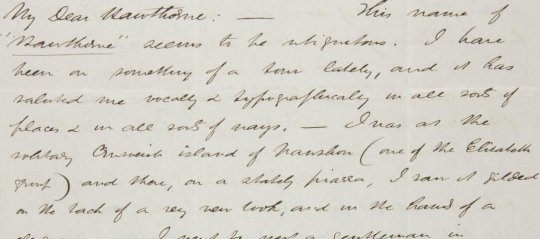

Read a (Love) Letter From Herman Melville to Nathaniel Hawthorne

There has been much speculation about this friendship.

Literary Hub Emily Temple

In 1850, Ticknor, Reed & Fields published The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic novel of repentance and slut-shaming. But this isn’t about The Scarlet Letter—it’s about one of the most fascinating friendships in literature. Because whenever I think of Nathaniel Hawthorne, I can’t help but think of Herman Melville.

Hawthorne and Melville met in 1850, and though Hawthorne was fifteen years older, and the two very different (Melville bombastic and highly emotional, Hawthorne much more reserved) the two hit it off right away. Soon afterwards, Melville published a very complimentary review of Hawthorne’s Mosses from an Old Manse, and the writers began an intense friendship that would last about two years before unexpectedly dissolving. There has been much speculation about this friendship, of course, and whether it may have been something more. As Jordan Alexander Stein put in in LARB, “All we are left with are representations of Melville’s feelings, tantalizingly expressed without being particularly easy to pinpoint. Melville wrote of Hawthorne with undeniably sexy language. What proves more elusive are the feelings to which, with any precision, this language can be said to refer.”

For instance, in that aforementioned review, Melville writes: “[A]lready I feel that this Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul. He expands and deepens down, the more I contemplate him; and further, and further, shoots his strong New England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul.” Which sounds like, well, you know.

But one of the best examples of this is the wildly flirtatious, possibly scandalous (magnets indeed), letter below. After Hawthorne read Moby-Dick—which was dedicated to him—he sent Melville a letter. That letter has not survived (nor any of Hawthorne’s letters to Melville—which begs the question: why did Melville destroy these?, but anyway), but Melville’s response, written in November of 1851, suggests that his friend rather liked his novel. So is it a love letter? Even if they were never more than friends, I’d have to say yes. I mean, “Knowing you persuades me more than the Bible of our immortality,” and “I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces”? Damn. Romantic or not, that’s some passionate correspondence.

Pittsfield, Monday afternoon.

My Dear Hawthorne:

People think that if a man has undergone any hardship, he should have a reward; but for my part, if I have done the hardest possible day’s work, and then come to sit down in a corner and eat my supper comfortably—why, then I don’t think I deserve any reward for my hard day’s work—for am I not now at peace? Is not my supper good? My peace and my supper are my reward, my dear Hawthorne. So your joy-giving and exultation-breeding letter is not my reward for my ditcher’s work with that book, but is the good goddess’s bonus over and above what was stipulated—for for not one man in five cycles, who is wise, will expect appreciative recognition from his fellows, or any one of them. Appreciation! Recognition! Is love appreciated? Why, ever since Adam, who has got to the meaning of this great allegory—the world? Then we pygmies must be content to have our paper allegories but ill comprehended. I say your appreciation is my glorious gratuity. In my proud, humble way,—a shepherd-king,—I was lord of a little vale in the solitary Crimea; but you have now given me the crown of India. But on trying it on my head, I found it fell down on my ears, notwithstanding their asinine length—for it’s only such ears that sustain such crowns.

Your letter was handed me last night on the road going to Mr. Morewood’s, and I read it there. Had I been at home, I would have sat down at once and answered it. In me divine maganimities are spontaneous and instantaneous—catch them while you can. The world goes round, and the other side comes up. So now I can’t write what I felt. But I felt pantheistic then—your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God’s. A sense of unspeakable security is in me this moment, on account of your having understood the book. I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb. Ineffable socialities are in me. I would sit down and dine with you and all the gods in old Rome’s Pantheon. It is a strange feeling—no hopefulness is in it, no despair. Content—that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.