#misogyny. but I think about that post a lot and it exemplifies a lot of what I'm trying to say when I talk about how people discuss

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Since I'm especially on a tear about this: I also wish people who claim to enjoy fictional women would ask themselves if they still take an interest in female characters when those characters are not specifically designed to be universally-liked?

#I'm not talking about 'women who are not good people'#I'm not even talking about 'women who are a mess/extremely flawed' necessarily#I'm talking about women who were not meant to be hashtag relatable and just exist in the story as they are#whose function is not just to be as palatable as possible.#like...are you normal about women when you don't directly relate to them basically. are you normal about them when the point isn't to#cater to you#hold on I'm going to go find a post real quick. it talks about misogynoir and fandom racism which are NOT the same as general#misogyny. but I think about that post a lot and it exemplifies a lot of what I'm trying to say when I talk about how people discuss#characters and discuss fiction in general#mel screams about fictional ladies again#and I know that this is The Women Blog and that's the reason a bunch of you are here. so I don't really know what me talking about this is#really going to accomplish after a certain point because if the people watching me scream into the void didn't on some level already#care or know this they probably wouldn't be following me or looking through my blog?#but I do also need to Uncork My Thoughts™ sometimes and unfortunately that usually means flinging them at tumblr lmao

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

here’s a question, do you think Blake’s responses to Rose would be fundamentally different if Rose was a guy? cause like- there’s Absolutely misogyny to it, as is, but I always thought Blake would’ve reacted like a cat being shoved in a bath to anyone trying to “tell him what to do” (quote unquote).

genuinely could not keep reading pact until i blake misogyny posted because he's sooo bad. he's literally worse than brian. like he's out here making brian look like a feminist. the thing that really sucks about Blake Misogyny is like.

brian will espouse misogynistic gender essentialist viewpoints he believes to be The Natural State Of The World, but in the context of his social environment, it's sort of just him beating himself against a brick wall. if it doesn't successfully alter his social environment to his preferences--which it never does--he'll get crotchety about it, but he's really not manipulative or vitriolic about it. it has 0 impact on the behavior of his female teammates, and he ultimately has to live with that. sure, in a different circumstance he might be able to socially steamroll over women, but as-is all he's doing is giving himself a concussion.

blake, on the other hand, is misogynist with plausible deniability. which is how vast portions of misogynistic behavior presents itself! obviously men believe (& frequently outright say) the things brian says, but they also have consistent interactions w/ women they have material power over where they demean, exert control over, and expect the women to cater to them--all while never directly bringing gender up and thus leaving them with enough plausible deniability that someone can go "well, he might respond the same way if she was a man, right?"

the answer to that question doesn't matter--even though it's very plausible that rose would be afforded far more respect if she was a man, it's insidiously impossible to prove it (which is part of the point of the behavior!), and either way proving it is irrelevant to our ability to point out the ways in which blake's interactions with her are already fundamentally misogynist.

as i've already mentioned, he does a lot of expecting her to "compromise" where "compromise" just means "you do what i want and i put up with the agonizing ordeal of knowing that you're not 100% happy about it," and he's also really prone to putting the burden on her to "communicate" while being fundamentally hostile to sentiment which even remotely infringes on his utter control over a situation (& subsequently over both of their survival). not to MENTION how gendered their division of labor is. you know how, 4 example, men are the ones supposed to know how to fix a car/drive (& are subsequently given the power of freedom of independent movement) whereas women are the ones supposed to do, 4 example, the laundry (confers no power, is labor which consistently services the man in the household)? similarly, rose is the one who does consistent domestic labor--i.e reading/researching/memorizing information to support blake with (thus consistently lowering his workload without having influential power over his behavior)--whereas blake holds power over infrequent & power-conferring tasks like deciding what they're buying* or calling all of the shots in a social interaction.

(*while mundane and laborious financial decisions are usually the woman's responsibility, like what to buy for dinner each week, the infrequent & high-stakes circumstance of purchasing survival supplies mean that blake is in fact the one holding power by being responsible for determining what weapons/etc to buy.)

also, to circle back to the topic of blake's expectations regarding "communication" for a second, i think this post is an exceedingly good explanation of exactly how that little dynamic works between them. hint: it's also him being misogynist. (yes, that post is mandatory reading for this post.)

all of these points culminate in this awful little exemplifying example of his behavior here in 2.1:

“Don’t worry about me if you’re not going to worry about yourself,” Rose said. “You look as tired as I feel, and since you’re the one making the big decisions, like when to go out and-” “Woah,” I said. “Woah, woah. You’re talking about this?” “About going out with Laird.” “I thought we weren’t fighting.” I could see her expression change. Barely restrained frustration, slowly but surely being covered up, hidden behind a mask. “We’re not. Nevermind. I got carried away. I’ll meet you downstairs in a bit, and then we’ll go?” A big part of me wanted to argue. To press the issue. To air grievances and get things on a more even keel. To convince her that I didn’t want her as a slave or a servant. Except we had more pressing matters. Better to find a way to show it to her rather than tell her. “Sure,” I said.

he's:

dramatically interpreting rose mentioning that he's been the one to make big decisions thus far as "fighting," manipulatively smothering both her ability to acknowledge their social dynamics + division of labor & her ability to even approach critiquing his decisionmaking--because how can she criticize him, when even mentioning a circumstance that turned out badly, with zero focus on his errors, results in him treating her as if she's being cruel?

again internally focusing on the idea of "communicating" ("airing grievances/getting on a more even keel"), but outright stating that the intended outcome of the "communication" he wants to have is "to convince her that he didn't want her as a slave or a servant"--in other words, he's viewing her feelings as something inaccurate that need to be corrected and brought in line with his viewpoints vs. as possible indicators that he needs to alter his mindset or behavior

sure, he purchases the bike mirrors as part of his attempt to "show it to her," but without self-awareness regarding how he's treating her, it will ultimately just be an attempt to "convince her" vs to genuinely address her concerns. i actually find it hard to believe that she was smiling about the bike mirrors when he was shopping for them--i don't think she would have any reason to read it as a genuine shift in his mindset & intentions. i'd be willing to guess that she had something else going on over there she was smiling about and he coincidentally caught her at the right moment to misinterpret it as being about bike mirrors.

in conclusion: "damages 2.1" more like. Damaging your relationship with rose thorburn by being a bitch idiot misogynist

#ask#pact time#pactblr#not even done with 2.1 but i HAD to blake misogynist post before i could keep reading#enjoythis post please. because i worked hard to make my rusty car brain go for it :(#special brian laborn feature because i love him

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re your tennis post tags pls talk about misogyny and men's vs women's tennis thank uuuuu (sidenote I don't really watch tennis but are skirts mandated for women to wear? Are dress code rules in general that strict?) 🙏

(follow up on this) there is a far more in-depth post on this to be made, but not for now. this is really mostly just. bits I cut... pasted together

here's a little more detail on the differences between the men's and women's games:

with the exception of a few mixed doubles competitions, men and women are always competing separately - and they are different tours to follow. this is true of both the type of game being played as well as the competitive picture. the men's game is more dominated by the serve, and having a good serve is pretty much a non-negotiable element of being a top player. this is also the shot that is most influenced by height (and yeah, obviously men do tend to be taller). the serve/return dynamic is fundamental for more genders, but it's more important in the men's game the modern men's game tends to involve a lot of high margin aggression, exemplified at the highest level by djokovic and formerly nadal. there's generally a lot of power play from the baseline... big serves, big 'serve plus one' forehands - aka the third shot of the point. also, big serving counterpunchers/defensively-inclined players are mostly only a thing in the men's game. the women's game has more breaks of serve, and also... a little more contrast in what type of playstyles you can use to succeed? the broad dichotomy fans will often talk about are 'bashers', highly offensive players with very high counts of winners and errors, and 'pushers' highly defensive players with low counts of winners and errors. there's also a bit of a third cluster, the players who rely on a lot of variety and mixes of spins and speeds to make their game work. while these broad distinctions also exist in the men's game, with women you can get a bit more extreme in how purely offensive or purely defensive players are obviously, it's not as straightforward as that. within the current men's top ten, you have high variety offensive all rounders like alcaraz, baseline high margin bashers like rublev (sinner is a more fully developed version of this basic archetype), and defensive grinders like medvedev. on the women's side, swiatek at her best exemplifies high margin aggression, with more topspin that she uses to aim for bigger targets than the typical basher. sabalenka is a little more basher, but both her and rybakina aren't the 'purest' versions of bashers either. gauff is the closest the current top ten has to a pusher. look, these are just very, very broad generalisations - but men's tennis doesn't have a penko (or not as successful) and women's tennis doesn't have a hurkacz (the closest you get is haddad maia imo, but that's more somebody who's neutrally trading than pushing)

anyway, one of the fun things about tennis is that you do have these two clearly distinct flavours with different competitive balances and different types of match-ups to engage with. I think it's quite natural to gravitate towards one or the other, to feel more passionately about one tour or the other. I was going to include a note about how that's completely fine, but in all honesty I am running a little low in patience with fans who completely refuse to follow the women's game. yeah, I'm biased, I think it's a lot better than the men's game right now - but also I do still watch the men, and often there's a lack of willingness to even engage with the wta at all. the women's tour can be a bit more volatile and you do need to open yourself up to a scary world where more than three players are contenders in any given slam, but like. just enjoy that depth of field. there's several players who are still plenty consistent if you need that to orientate yourself

then on the misogyny stuff, specifically in the current game and not on a historical level:

well. where to start. at pretty much every mixed gender tournament, there's scheduling discourse and men being given the more prestigious slots. roland garros is a repeat offender on this count. a few years back they introduced 'night sessions' just on philippe chatrier (the main court) where they have a different ticket for just one match, and it's also a thing where they have a specific deal with a different broadcaster within france (aka amazon prime). this year, not a single women's match was scheduled during that session. thing is, none of the players really like the session so most women aren't exactly clamouring for it either (honestly everything about these sessions just sucks) but it's still...? not great? people use the best of five versus best of three thing as a justification (which I find inherently frustrating because I too would prefer bo5 for women) but then don't have it for one match? us open night sessions have two matches, one men's and one women's, which gets rid of the problem

also roland garros did this thing where they just scheduled all the women's matches early in the day, basically as if to get them out of the way? the first session of the day is called the graveyard shift, the vibes are weird and there's like three people watching on the court, it's proper depressing when a slam quarterfinal is happening with that lack of atmosphere

of course, you do also have the exact same flavour of faffing about in tour level matches, where the length of product argument falls away (everyone plays bo3). we don't generally have cases any more where it's just men's matches being scheduled on the main courts or whatever, but more insidious stuff

so we've gradually had a switch from one week masters/1000 tournaments to two weeks, for a bunch of commercial reasons even though... are there any fans who like this? it really just does not work, like there's a week where basically zero big names are playing and it feels like you're just sitting around forever waiting for the tournament to properly kick off. but the gender element is in how the tournaments balance the men's and women's scheduling, where often they front load the women's matches and rush through a bunch of rounds, which means that in the second week you suddenly end up in this situation where the women's tournament has almost completely been played while the men's tournament gets to hog more of the spotlight

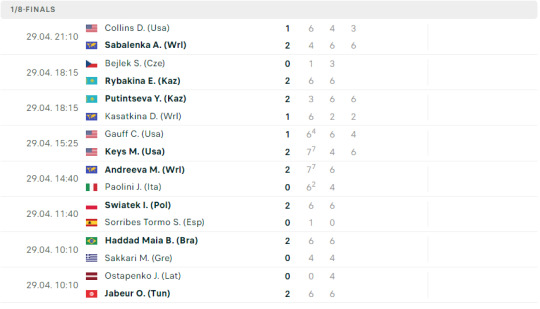

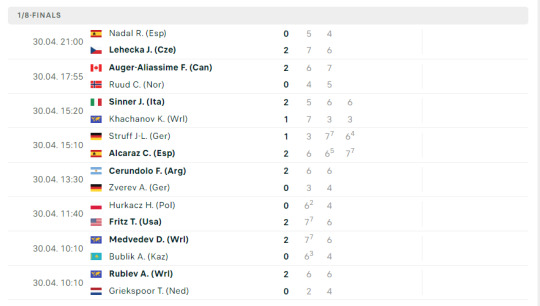

a darkly funny example of this came at madrid this year (because of course it was madrid), where the men's tournament just straight up sucked while the women's tournament produced several all time classics. so it meant that for instance on the 30/4, we had eight men's matches and two women's. on the 2/5, we were supposed to have two men's matches and the two women's semis with the men getting their own day on 3/5, but in a brave example of being an #ally the two men's matches that day managed a full set total between them

there's also like. crowd issues. part of this is because society just straight up sucks and doesn't show up as much for women's tennis. part of it is also a complete failure in marketing. part of it is the wta's organisation and calendar decisions - like figuring out where they'll host their finals like two weeks before d-day or putting a bunch of tournaments in the middle east where the crowd numbers are.... not great. just depressing, this roland garros was also really bad for that

accessibility. men's tennis has tennistv, women's tennis has... geo-locked wta.tv, which does also suck. any mixed gender channels tend to make some howlers in terms of what they're choosing to show. can't get people into the sport if they can't watch it!!

prize money outside of the slams is still very unequal

general wta incompetence. includes all the stuff mentioned above, as well as various other mishaps. the marketing is terrible, you can see it in the highlights and social media content they put out. the highlights game is genuinely laughably bad, you have fans do a way better job but then they get hit by copyright claims

sometimes we do get women's players speak out about some of these issues, like the general outcry during madrid last year prompted by cake gate. it's rarer than would be ideal

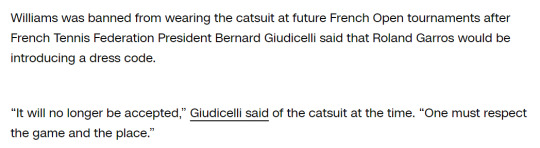

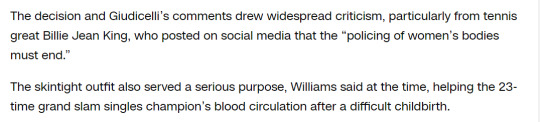

also just various non-structural bits of misogyny, including how the game is treated by journalists or individual men's players and so on. anyway, on the dress question - women are allowed to wear shorts, BUT there was a big controversy a few years back when serena wore a ''''catsuit'''' to roland garros and the rules were changed for the subsequent year to ban it

this was back in 2018, mind you. here's an article about some of the historical controversies relating to women's outfits. tennis has a weird problem with women just wearing sports leggings, which. that's basically all this is, like they're not exactly uncommon, are they. I wear them while playing tennis most of the year

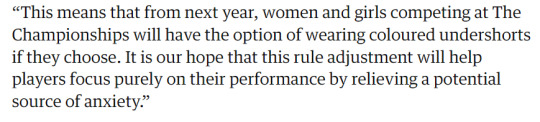

the other recent more positive development is that wimbledon finally last year agreed to let players wear dark underwear in response to protests about how needlessly unpleasant the situation was for women worried about their periods

which is kinda. yeah this is good but why on earth was this still a thing

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

PLEASE tell us why you hate the dumb dragon prequel show??

Oh god, I've talked about it so much over on my main @ripley-stark that I forgot that I haven't really made my opinion known here. If you want the long answer, I've been posting voraciously under the #alicent hightower and #hotd tags since the show started airing.

Tl;dr, I really wanted to love this show! There are lots of good character concepts and... attempted... themes, and the acting, costume design etc is stellar. I think that's one of the reasons why it still occupies my thoughts to this extent and I haven't just moved on. I was extremely hesitant going in because I find the Targs incredibly boring and distasteful, but I was genuinely shocked to love 1.01-1.03. I had a few blissful weeks of thinking, Not me... liking the Targ show?

I should've known. After that point it started to become demonstrably clear that the writers were only interested in glorifying literally every action taken by Rhaenyra, Daemon, and Viserys at the cost of any other character, especially Alicent. No one has an arc. No one has a consistent personality that coheres with their actions/backstory. All POV scenes center around Rhaenyra. Anyone against Rhaenyra, Daemon, or Viserys is a villain--a misogynist in particular.

There is a blatant double standard between the behavior of these three and of any other character. Everyone on the show commits morally gray acts, but actions are portrayed as good or evil based on which character commits them. The characters don't drive the plot; they exist to exalt Rhaenyra through the events of the F&B story the show is based on. Rhaenyra has no flaws. Alicent has every flaw. Rhaenyra is always the victim and Alicent is at fault for every aspect of her own and Rhaenyra's circumstance. In fact the show goes out of its way to exemplify how Alicent is inferior to Rhaenyra in every way and has no valid reason to go against her besides her own internalized misogyny.

This is not a show about a woman rebelling against a sexist system. It's not even a show about two compelling women navigating the patriarchy and vying for power. This is a show about Rhaenyra being correct all the time, about Rhaenyra being the model of behavior for all women. Her and her family's objectively evil and oppressive actions along the way to her goal were all justified because her being queen is the ultimate achievement for all womankind. Despite the fact that she is literally the richest and most powerful woman on the planet with a dragon and her rapist/pedophile/colonizer father and uncle's favor, other women are somehow her worst oppressors and should act more like her to be better people. #feminism.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is random but did you also avoid the Depp/Heard trial? Not because you didn’t care, but just because it was too overwhelming and unpleasant to engage with.

i did avoid diving too far into that sphere intentionally, though of course i still saw news about it through cultural osmosis and the high profile nature of the case, and some of the things online being so downright evil that others couldn't help but comment on them (understandably). i actually still have an article from the atlantic last year saved in my drafts about this (this piece), and i think it's an important, illuminating read, and i've actually been thinking about it a lot again over the past couple of weeks. :/ (the article author kaitlyn tiffany also wrote in 2020 about fandom conspiracy theories is also such an important piece imho, though a disquieting read.)

"

The case is complicated, and the testimony is rife with sordid, disturbing details. In short, Depp has taken Heard to court for defamation over a 2018 essay she published in The Washington Post that identified her as a victim of domestic abuse and sexual violence. Heard also made abuse allegations when she filed for divorce from Depp in early 2016, and was granted a restraining order against him.

Rebecca felt betrayed by Depp when Heard came forward with her story, and has since renounced her fandom. But she’s been positively horrified by the behavior of Depp’s other fans, who have spent the past several years trying to discredit Heard as a “gold digger” and a “monster.” (I agreed to identify Rebecca by only her first name because she was concerned about harassment from this community.)

...For Millennials in particular, she told me, fans’ sense of their own morality is deeply entwined with fandom. “We hang so much of our own identity on these things that we love,” she said. “So if those things are threatened, you either have to admit that you’re sort of a bad person for liking those things or you have to convince yourself that everyone else is wrong.”

Hilde Van den Bulck, a professor of communication at Drexel University, has studied the version of fandom that inverts its practices and creates a community of denigration. Where fandom tends to derive from a positive emotion (I love this actor; I love that character), anti-fandom draws from just the opposite, and nurtures negative feelings toward a famous person or character. Fans and anti-fans both express themselves through online sleuthing: They hang on the object of their fascination’s every word, and analyze every detail of that person’s wardrobe and hairstyling and self-presentation. “Anti-fans know as much about their object of anti-fandom as fans do about their object of fandom,” Van den Bulck said. Their relationship with the celebrity they despise is “often very deep, very emotional.”"

idk i have a lot of things i could write about and delve into with this given more current events, but this exemplifies a lot of where fandom's problems with women intersect with confused ideas about social justice and morality intersect with emotions about things we love intersect with the very incorrect idea that enjoying a work of art or an artist is equivalent to endorsement of everything they do, and it's so complex. absolutely we should hold people accountable, absolutely people should be called out for harmful actions and behavior (be that abuse, racism, misogyny, homophobia, -isms and hurt or disregard for others of any kind), and it should not be tolerated. at the same time, i do worry that overcorrection in tying things we enjoy to morality is leading to us punishing each other for the bad actions of individuals far out of our control, and that doesn't solve the problem or help uplift anyone.

sorry, this got super off-topic! but i understand why you tried to avoid it, because it was overwhelming and unpleasant and triggery, and revealed some ugly and shameful things about the way fans - even predominantly female ones - will behave and harass others online and how we need to curtail that going forward as best as we can.

#i was a fan of his as an actor and i'd not deny that. he's made many movies i adore but he's repulsive to me as a human now#so i still grapple with “can i reclaim (these films)”#and it's a shame it became so horrific and was splashed all over the media like it was#and treated like a sporting event instead of a very upsetting domestic violence case#it left some deep cultural wounds i think#anonymous#letterbox#abuse tw#he basically said last week that we're hypocrites bc all men are like this...yeah okay do you get your advice from mar*lyn mans*n? creeps

1 note

·

View note

Note

thank you for this addition! i think there are a few conversations you've pointed out here where, though they're not all coming from the same place, are cumulatively having the same alienating effect.

so for one thing I'm gonna take a stab in the dark and say there are a lot of people in fandom spaces who have at some point gone through the process of 'reclaiming their femininity', after some time in the 'not like other girls' mines as a kid/teen. i have also done a bit of this in my time, and i've seen more people talk about it in fandom spaces than I've seen anywhere.

so maybe this process felt in some way empowering for a lot of people here - that they discovered they could like things they thought they had to disdain, and that enjoying them gave them a flavour of in-group. I really believe the NLOG mentality primarily comes from girls who have been made outcasts by their female peers, and who in turn said 'well i don't want to be like you anyway'.

i think it's a very natural reaction, but as you get older you start to understand there's a lot of internalised misogyny that can fester in this mindset, and so now the NLOGs are made to look the bullies, and the feminine in-group their victims. which is... pretty unfair lmao, but if you can convince yourself you're now PART of that in-group, it's not so difficult to disdain that old NLOG mindset - that's not you anymore.

but as you say, i think the more harmful trend that carries over from this is this 'reclamation' of femininity, where it's made to fit anything you want it to just so you can feel like you do conform, just in more creative ways. which is.... weirdly contradictory, and also almost an extension of the NLOG mentality. so now in stark sister warfare you've got Sansa stans calling Arya an NLOG and you've got Arya fans saying Sansa exemplifies 'toxic femininity' and Arya some kind of more natural, organic femininity. and ftr i don't think anyone is winning here lol. but I think the issue in the middle is this odd possessiveness over 'femininity' as a trait.

to take this back to my original post, I guess my issue then is this idea that femininity is not a fundamentally neutral thing, that anyone can have in smaller or larger doses. going beyond just the stark sister warfare, there's this need to accommodate more and more traits within it that it becomes very gender essentialist - it's nurturing, it's romance, it's nature, it's the cosmos, it's fucking everything. the gnc character is not actually gnc, just a more fantastical kind of feminine.

so if you're a user who doesn't give a shit about femininity, and identifies more with the character's non-conformity, or their masculine traits, and yet all you see is this insistence on femininity, and this actual fury at the very idea that one might call XYZ gnc or masculine in some way, it's extremely alienating. it does just take away the language you have to describe your own relationship to gender, and replaces it with a universal 'femininity' that utterly insists upon itself.

and then ofc there's the other side of this, which I think is easier to boil down - like the reactions to butch Rhaenyra are just.... ppl hate butch women. they'll tolerate a kind of soft androgyny, but don't push it beyond that. and ESPECIALLY don't draw her with femme Alicent, because why does Alicent get all the femininity! that prized resource! why would you do THAT to Rhaenyra why don't you do THAT to Alicent! punish her she's so much more cold, and evil, and not nearly as motherly as Rhaenyra, and oh shit we've already struck like five different kinds of misogyny in this passage alone. i mean it doesn't even need explaining, these people do know deep down that they just think that drawing Rhaenyra in a butch way is degrading because to be butch is degrading, but they'll dress it up in progressive language because there's no way they're going to admit that. I've looked at their arguments and they don't hold up for two seconds, but doesn't mean they haven't done this dozens of times over.

anyway that isn't to say that I think femininity sucks or isn't interesting. I like that Brienne encompasses both masculinity AND femininity. I really enjoy how GRRM portrays theses as symbiotic sides of her, equal in worth. and I do think it's a shame that GOT turned Brienne into something so much flatter, who operates like a tin soldier 90% of the time. but we don't really need to overcompensate here by putting a 'feminine' spin on her masculine traits as well, or that old argument that she wouldn't have picked up a sword if she didn't have to she would've been happy just being Lady Brienne!!! (canonically, no. she would not)

and idk just.... femininity is not liquid gold we don't have to talk about it like this mystical nuance that every girl wears differently.

It’s not even just asoiaf fandom, it’s a pan fandom thing that showing women who are CANONICALLY GNC in gnc ways is considered misogynist. People were doing this about Vi from Arcane like a week ago

oh for sure. and you see people trying to expand the definition of femininity to fit all kinds of things, by in turn REDUCING masculinity by comparison to just a handful of undesirable, violent traits that you wouldn’t want associated with your fave. perhaps this is partially in response to how alienating femininity can be, and ppl trying to carve it into something more accepting that they can belong to. but I think there should be limits to that, bc the result is othering those who just don’t care for femininity, and embrace nonconformity. and this insistence that drawing out a character’s masculinity/non conformity in fanwork is insulting and degrading but capitalising their femininity is empowering - well that’s just so fucking transparent isn’t it lol.

btw though it’s worth adding that I think the dialogue is different where concerns women of colour, as there’s a very different history there as concerns a kind of…. othering through masculinising?? and I saw a dialogue taking place re. this in a different fandom today, concerning fanwork of a character portrayed by a black woman, and I was just like…. there are two very different conversations to be had about this. so would add that on the above, im talking about the discourse surrounding gnc white female characters.

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

TBH I think the whole "You didn't have an issue with this in 'insert x show here' but you have an issue with it in RWBY? What are you, sexist?" thing can easily be defused with a simple, "How did RWBY present this plot-point compared to the show I like?"

Sure, technically Cinder Fall and Darth Maul are the 'same' character, but how are the two presented in their respective shows? Cinder eats up screentime and none of it goes anywhere and gets frustrating. Maul is a relatively minor villain that had one season's worth of attention in CW and then was the villain of a few episodes throughout Rebels before getting killed off.

The only reason someone would be confused as to why people like Maul but hate Cinder is if they just read the two's respective wiki pages.

Really the whole "Your issues with RWBY are just subconscious misogyny" is just some people wanting to slap labels onto others so they can feel validated on not agreeing with their opinions.

Generally speaking, I'm wary of any take that boils down to a single sentence, "You're just [insert accusation here]." Not because such accusations are always 100% without merit—with a canon dealing with as many sensitive subjects as RWBY, combined with a fandom as large and diverse as it has become, you're bound to come across some people whose "criticism" stems primarily from bigotry—but because such dismissive summaries never tackle the problem a fan has pointed out. If one fan goes, "Ruby's plan was foolish because [reasons]" and the response to that is "You just can't handle a woman leader," then that response has failed to disprove the argument presented. The thing about "criticism" based in bigotry is that there isn't actually a sound argument attached because, you know, the only "argument" here is "I don't like people who aren't me getting screen time." So you can spot that really easily. The person who is actually misogynistic is going to be spouting a lot of rants about how awful things are... but very little evidence as to why it's awful, leaving only the fact that our characters are women as the (stupid) answer.

And yes, there is something to be said for whether, culturally, we're harder on women characters than we are men. Are we subconsciously more critical of what women do in media simply because we have such high expectations for that representation and, conversely, have become so used to such a variety of rep for men—including endlessly subpar/outright bad stories—that we're more inclined to shrug those mistakes off? That's absolutely worth discussing, yet at the same time, acknowledging that doesn't mean those criticisms no longer exist. That's where I've been with the Blake/Yang writing for a while now. I think fans are right to point out that we may be holding them to a higher standard than we demand of straight couples, but that doesn't mean the criticisms other fans have of how the ship has been written so far are without merit. Those writing mistakes still exist even if we do agree that they would have been overlooked in a straight couple—the point is they shouldn't exist in either. Both are still bad writing, no matter whether we're more receptive to one over the other. Basically, you can be critical of a queer ship without being homophobic. Indeed, in an age where we're getting more queer rep than ever before, it's usually the queer fans who are the most critical. Because we're the ones emotionally invested in it. The true homophobes of the fandom either dropped RWBY when the coding picked up, or spend their time ranting senselessly about how the ship is horrible simply because it exists, not because of how it's been depicted. Same for these supposed misogynists. As a woman, I want to see Ruby and the others written as complex human beings, which includes having them face up to the mistakes they've made. The frustration doesn't stem from me hating women protagonists, but rather the fact that they're written with so little depth lately and continually fall prey to frustrating writing decisions.

And then yeah, you take all those feelings, frustrations, expectations, and ask yourself, "Have I seen other shows that manage this better?" Considering that RWBY is a heavily anime-inspired show where all the characters are based off of known fairy tales and figures... the answer is usually a resounding, "Yes." As you say, I keep coming across accusations along the lines of, "People were fine with [insert choice here] when [other show] did it," as if that's some sort of "Gotcha!" moment proving a fan was bigoted all along, when in fact the answer is right there: Yes, we were okay with it then because that show did it better. That show had the setup, development, internal consistency, and follow through that RWBY failed to produce, which is precisely what we were criticizing in the first place.

What I also think is worth emphasizing here is how many problems RWBY has developed over the last couple of years (combining with the problems it had at the start). Because, frankly, audiences are more forgiving of certain pitfalls when the rest of the show is succeeding. I think giving a Star Wars example exemplifies that rather well. No one is going to claim that Star Wars is without its problems (omg does it have problems lol), but there's enough good there in most individual stories to (usually) keep the fans engaged. That doesn't mean that they're not going to point out those criticisms when given the chance, just that disappointment isn't the primary feeling we come away with. Obviously in a franchise this size there are always exceptions (like the latest trilogy...), but for most it's a matter my recent response to The Bad Batch, "I have one major criticism surrounding a character's arc and its impact on the rest of the cast, and we definitely need to unpack the whitewashing... but on the whole yes, it was a very enjoyable, well written show that I would recommend to others." However, for many fans now, we can't say the same of RWBY. Yang getting KO'ed by Neo in a single hit leads into only Blake reacting to her "death" which reminds viewers of the lack of sisterly development between Yang and Ruby which segues into a subpar fight which messes with Cinder's already messy characterization which leads to Ruby randomly not using her silver eye to save herself which leaves Jaune to mercy kill Penny who already died once which gives Winter the powers when she could have just gotten it from the start which results in a favorite character dying after his badly written downfall and all of it ends with Jaune following our four woman team onto the magical island... and that's just two episodes. The mistakes snowball. RWBY's writing is broken in numerous ways and that's what fans keep pointing to. Any one of these examples isn't an unforgivable sin on its own, but the combination of all of them, continuously, representing years worth of ongoing issues results in that primary feeling of, "That was disappointing."

Looking at some of the more recent posts around here, fans aren't upset that Ruby is no longer interested in weaponry because that character trait is Oh So Important and its lack ruins the whole show, they're upset because Ruby, across the series, lacks character, so the removal of one trait is more of a problem than it would be in a better written character. What are her motivations? Why doesn't she seek answers to these important questions? Why is her special ability so inconsistent? Where's her development recently? What makes Ruby Ruby outside of wielding a scythe and wanting to help everyone, a very generic character trait for a young, innocent protagonist? We used to be able to say that part of her character was that obsession and we used to hope that this would lead to more interesting developments: Will Ruby fix/update their weapons? Is her scythe dependency the reason why others need to point out how her semblance can develop? What happens if she is weaponless? Surely that will lead to more than just a headbutt... but now we've lost hope that this trait will go anywhere, considering it has all but disappeared. Complaints like these are short-hand criticism for "Ruby's character as a whole needs an overhaul," which in turn is a larger criticism of the entire cast's iffy characterization (Who is Oscar outside Ozpin? Why was Weiss' arc with her father turned into a joke and concluded without her? etc.) and that investment speaks to wanting her to be better. We want Ruby to be a better character than she currently is, like all those other shows we've seen where the women shine. Reducing that to misogyny isn't just inaccurate, but the exact opposite of what most fans are going for in their criticisms.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

final thoughts about 1984

i lied. this is final but its not about 1984, because it never was about 1984, it was never even about my post or the things i said. its about the version of me and my arguments that’s been constructed by other people, that they’ll continue to argue with.

the post has been circulated thousands of times, screenshoted to twitter to have hundreds of people dunk on me and call me stupid, say i don’t know how to read, etc. i got hate messages telling me to commit suicide and to detransition. it was funny at first. but i’m tired. i never wanna read the year 1984 again. ive started to doubt myself and wonder if there was a secret truth that all of these people had tapped into that i somehow missed and nobody has ever been explain to me, that nobody else has ever written about in all of the writing ive found on the book and everybody gets but me

first, i twote what i twote

i said what i said. could i have worded it better? YES. but i was making a kneejerk reaction to a poorly written post, that was worded in and simple way so i phrased it poorly.

i do think that reading about rape in a classroom is inappropriate and potentially traumatic to readers, i think that experiencing violent misogyny without a discussion is harmful. i dont actually care what orwells intentions were because i dont know them and neither do you. hes dead. his words still hurt people and thats not okay to expose people to without a discussion about it.

i also think that media analysis can be taught with any work. you can perform media analysis on the goddamn mcu and find something worthwhile there. i fundamentally think teachers meeting students where they’re at, validating their interests and teaching the same strategies learned for classics! despite reading lots of classic literature, i never learned how to perform actual proper media analysis until i was in college! my reads of classics were often dismissed by teachers, i was forced to memorize their analyses instead of being able to think critically about works on my own! meet students where they’re at! encourage passion! use it to help teach new techniques and help them engage in and love material!

you don't know me

you know, in the tons and tons of messages and random ass people coming into my DMs demanding a debate, i realized something. they’re not arguing with me. they’re arguing with the version of me that exists in their head. i remember in particular somebody came at me and said “why do you think there’s no merit in 1984 because of some bad things” and i replied that i never said that. they said my message wasn’t clear enough so of course everybody would assume that.

i wrote a two second response girl! i wasn’t trying to create an essay for people to respond against. but who i am doesn’t matter. it never really did. people have constructed me to be the type of person who exemplifies fandom and cancel culture or whatever coming for classic novels, who thinks that anything new and shiny with fandom is better, and that i don’t know how to read and think anything problematic or with hard topics is canceled and not worth any merit.

the truth is i haven’t read a fanfiction since i was 12 or engaged with a fandom since i was 17. my two favorite works of fiction are boogiepop and we know the devil, both of which deal with really heavy topics, have main characters who make bad sloppy choices and hurt people. neither of these works have big fandoms. i think fandom has merit, and i am interested in people who perform literary analysis on popular nerd culture texts. that’s not me, but i support peoples’ right to do that. but i like indie art! most of the media i consume is experimental indie videogames, and a lot of lgbtq independent projects.

again though, who i am doesn’t matter, because nobody here was ever arguing with me, they were arguing with an idea of me based on two sentences, a being constructed from those terms with other peoples assumptions plastered on. i’ve just become somebody to put that being on. that’s kind of how everybody talks to each other online, and i’ve come to recognize that now. hell, i’ve been the perpetrator of that stuff towards other people online too! thats why i don’t hang out online anymore, why i don’t read arguments anymore, and why i am trying not to let the nasty stuff people say to me bother me because it was never about me

can y’all leave me alone now?

even if 1984 was worth all this discussion, i want to be able to turn anonymous messaging on again, i want to be able to have my DMs open without it being an invitation for people to accuse me of not knowing how to read. go bother somebody else with your time. you have the time to write to some random ass bitch over 1984? write letters to prisoners to help alleviate the trauma of the carceral system! go harass nazis on twitter if you want somebody to be mean to! instead of telling me to detransition, go cry about 14 year olds sending u anime jpegs or whatever the hell terfs do! i promise y’all it is NOT deep enough for you guys to be hounding me the way you do. your time is valuable! dont spend it bothering random bitches on tumblr!

if youre gonna bother me over some typo on this post consider that i don’t actually give a shit and you could be spendin the time having sex instead or doing something else that makes you happy. i’m not reading this post again and i’m not talking about this topic again. deuces

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

That one thread on writing advice by Lily Orchard (see post because the thread won’t open for me on Twitter for some reason?) really exemplifies how ridiculous the whole anti vs anti-anti fighting is.

Like, not only is the OP of the twitter thread framing “personal preferences in media“ (which are totally okay to have, duh) as “writing advice“ meaning “If I don’t like it you CAN’T write it!“ but it’s also very telling that she’s mentioning these tropes appearing in children’s media (like SPOP and Star Wars) and using the names of common fanfiction tropes.

Because... for most people who engage in these debates, the main media they consume IS children’s shows and fanfiction, and those are, by default, more black and white and less complex than adult media and fiction (even with fanfiction having adult themes, it’s very one-track minded). So, by combining that and fandom being mostly made up of young people and how fandom is often as vehicle to spread political ideas these days... you get a very black and white debate of what is “okay“ to depict in media.

So on one side you have “you CAN’T write Enemies-To-Lovers“, “you CAN’T redeem evil characters that have killed more than *insert ridiculous arbitrary number*“, “you CAN’T use Bad Words“; and on the other side you have “actually if you think it’s fucked up that I write graphic rape and pedophilia fics purely because they excite me, you’re engaging in censorship“ when the correct answer is “It’s okay to include dark themes in media, and the degree of how they’re included will vary depending on who that media is aimed at, it’s also okay to criticize how these themes are included in media and people have every right to say that they think you’re fucked up if you write graphic pedophilia in a way that’s meant to be titillating“

Because there’s ways to write, and ways to shape a scenes and to frame it. And it’s possible to frame the same dark event as either something to condemn, or as either something the author seems to be okay with. And, even then, regardless of how these issues are framed, people are still going to like/dislike certain portrayals and *gasp* consume media that there’s elements which they criticize!

For example, one of my favourite books, ever, is The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. I seriously consider it to be one of the best pieces of Hispanic literature (and she IS the Hispanic author most read in the whole damn world for a reason, the woman is just very very good!), but that book also has one of the main characters rape a girl under his service, this rape produces offspring and then at the end of the book the girl’s grandson rapes and tortures this main character’s granddaughter. In both instances, you have women suffering and paying for men’s crimes. I, personally, don’t have a problem with the scenes existing in the book (it is a very brutal book and it talks a lot about violence, and politics and history, and a military dictatorship, so dark themes ARE to be expected) what I have a problem with is that, as the years in-book pass, one of the main characters who was a rapist and a horrible man and an abusive father gets “redeemed“. Why? Because he’s old now and he’s nice to his granddaughter and age has softened him. And yeah, that’s bullshit! That’s infuriating! That made me want to throw the whole book out. And THAT doesn’t stop the book from being a brilliant work and one of my favourites ever. I also recognize the time period it was written in and how the story has autobiographical components on Allende’s part.

I can critize the depiction of misogyny in this book and still love it. Just like other people can hate it. I can also be obsessed with Catradora and dislike Reylo (when both follow the same trope, kind of) because of how each is written. I can also enjoy the dark themes in many stories, and think that, during fanfiction browsing, I’ve come accross way too many fics in which people write noncon (aka RAPE) in a way that’s not meant to be seen as a condemnation of it, but titillating (case in point: Dragon Age, there’s people absolutely obsessed with writing Fenris being explicitly raped based on a throwaway line that implied it in the game, and so many definitely write it in a way that feels like they get off on it!) There’s a clear difference in framing a fictional events as a good or a bad thing. And it’s a skill all writers/media creators need to learn. And I can’t make people write one thing or another, but I have the right to criticize it. That’s what the whole conversation is about, really, but making it into a black and white “NO, you CAN’T write ANYTHING that’s dark“ vs “You can write absolutely anything because it’s fiction and fiction never has anything to do with reality ever“ argument, when neither of those positions are true, is very immature.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

im super conflicted abt hawks atm but i was thinking abt his parallels with shigaraki and i was wondering kinda why there's a difference between wanting 'redemption' (i dont think this is the right word but i cant think of a better one 'want better' maybe?) for shigaraki but not for hawks? is it bc he made a permanent decision to kill twice as essentially an agent of the state?

Just to preface, I don’t think I’m objectively right for just wanting Hawks to eat shit immediately in the next chapter. I’m just complaining because a lot of people who “love both Hawks and Twice” and “think Hawks was wrong, but…” are hard to get away from without going in the other direction toward a group of people who have shitty fandom behavior, whose opinions about the Hawks/Twice situation are (unfortunately) much closer to my own. I don’t think there’s necessarily a “correct” way to feel about Hawks, but I feel differently than a lot of people I see around (who, ironically, are the ones insisting that there’s a “correct” way to feel about Hawks), and that’s frustrating. I want to be done with Hawks. I don’t want him to get any more focus in canon, I don’t want to see more posts about how Hawks committing murder is an indication of inner turmoil instead of him choosing a side, I don’t want to keep running into posts that tack on “but Hawks is also sad/a victim” in discussing what’s pretty clearly a tragedy for Jin and the LOV that Hawks was completely and 100% solely responsible for.

But, yeah, sure. I’ll also explain what I think is the difference between Tomura and Hawks:

1. Part of it is emotional and not logical for sure. I love Jin a lot. He embodies the person who has faced incredible adversity, and still comes out on the other side ready to love and open his heart to others, moreover to protect others. I’m not like that at all, but I think it’s very admirable. So in that sense, it hurts on a personal level to lose him over anyone else, and I can’t not associate that with Hawks, since he’s the killer.

2. Jin is a significant death. The nameless minions that Tomura has killed (many of whom were active “Quirk supremacists”) don’t mean anything to me compared to Jin, and?? Through the lens of narrative, I think that makes Tomura more forgivable, because I genuinely have no interest in there being any plot “resolution” with, like, the dead anti-mutant cultists, because I just do not care about them.

3. Tomura, especially early Tomura, has threatened to go places that are unforgivable, like leaving All Might’s students dead and forcibly bringing Bakugou over to their side (whatever terrible procedure that may have entailed). The difference is that the narrative never actually allowed him to cross that line by actually killing the kids, who we do care about as characters, so while the intent in itself is pretty awful, he was never allowed to complete the action that would take him over to the point of no return. Hawks, however, did cross the line by killing someone who we care about and who is narratively established as a “good person,” who even Hawks concedes is a good person.

3. a. I don’t like the MLA ideologically and I don’t like the decision to have the LOV team up with them. But, again, their takeover plan has been stopped in its tracks, which I’m actually fine with to prevent the LOV from crossing the moral event horizon, but that’s, like… completely irrelevant to me thinking Hawks shouldn’t have killed Jin.

3. b. Though there’s still a chance for Tomura to cross the moral event horizon, and I’m not going to convince myself that it won’t happen. If it’s going to happen, I think it’s highly possible that it might happen in this arc, because now Jin is dead and we know how Tomura and the LOV have historically responded to their friends getting hurt. I, and many others, have called Jin the “heart” of the LOV (his name is also literally written with the kanji for “benevolence”), and now without him, there is no remaining heart nor goodwill.

4. Although both Tomura and Hawks are, on one level, fighting on behalf of the ideals that they were “raised into,” their fights happen in very different ways. The MLA arc in particular made clear that the villains are, in part, fighting for their very survival in ways heroes just aren’t. The threat that the LOV were living under was constant—when it wasn’t heroes or other villain groups, it was trying to find money and shelter and essential upkeep. Hawks may not be “free” from the HPSC or the occasional villain attack, but he’s free from those constant material struggles. He’s not an “underdog.”

4. a. Tomura is also, in part, fighting to protect his marginalized friends. It’s for sure not on behalf of every marginalized person, but it’s certainly more than we’ve seen any pro hero fight for. The people Tomura is surrounded with are people who have never been protected nor cared for before, because they were not deemed “innocent” enough to deserve that care and protection, and Tomura continued to care for them even when it was troublesome for him to do so, when they disagreed with him, when they threatened him, and when they fucked up very, very badly.

4. a. i. Eri is an example of a victim who the heroes fought for, but she’s an easy case to want to love and protect: Overhaul was inarguably an abuser who wanted to elevate the yakuza, she was being used in extended torture-experiment sessions, she killed her father on accident, she’s a child, she’s innocent, she’s selfless, she’s well-behaved. It’s basically not even a question whether or not she “deserves” help.

4. b. It’s people who are difficult who get overlooked. Hawks and hero society are completely unprepared to protect and care for people who don’t behave as they’re supposed to. Hawks did not care for the LOV who didn’t personally befriend him. For the one he did, when Jin didn’t cooperate the way Hawks wanted, he went for the kill. It’s either being easy and “manageable,” or die.

4. b. i. Tomura has specifically spared two people who tried to kill him or actually succeeded in killing his ally, people who he explicitly hated or did not care for. So make of that what you will, I guess.

5. From a leftist perspective, it’s just impossible not to account for the fact that Hawks helps maintain a social structure that creates so much suffering. The question isn’t really whether AFO’s teachings to Tomura are better (they’re not, and I want Tomura to break away from them), but it can’t really be ignored that Hawks is enforcing an ideal that’s wildly popular. Why this matters is that Tomura doing the wrong things will be roundly condemned, and he’ll probably be “punished” for them; but heroes are very unlikely to be punished or held accountable for committing murder, especially if it’s “justified.”

5. a. This is problematic because it allows heroes, and the state, to define what a justified “emergency situation” is, and who can die in those emergencies. The people who are deemed killable “in an emergency” are usually those who are already marginalized; hence heroes can wait until those marginalized people get desperate enough to commit villainous acts, and then they can swoop in to arrest or kill them to widespread public acclaim.

5. b. Heroes (and law enforcement IRL) don’t address the roots of crime that lie in overarching oppressive structures like misogyny and capitalism. They don’t prevent theft by bringing people financial stability; they arrest people who were desperate enough to steal, and use those people to send a message to poor people everywhere. They make these conditions of desperation more permanent by punishing the most vulnerable people when they slip up, while doing absolutely nothing until the slip-up happens.

5. c. Heroes are punching down, and villains are punching up. That may not be the case with AFO, but I believe it with the LOV specifically, and I believe this matters because it’s exemplified between Hawks and Twice. Hawks targets someone who reached out to him, despite being hurt over and over again by types like him, who has dealt with poverty and fantasy mentally illness completely on his own, and kills him in defense of the very society that allowed all those things to happen to Jin. Hawks was given a choice: sympathize and relate to Jin, and acknowledge his well-founded grievances toward a dysfunctional society, or prioritize the safety and security of that dysfunctional society by permanently removing Jin from the equation. The choice he believes in is the choice he made.

5. d. In order for Tomura to make the same choice with the same implications, they’d have to be living in an alternate universe, in the Kingdom of AFO, where Tomura is a respected noble who infiltrates a rebel group who were going to “commit atrocities,” kills the one person who offered him a way out of AFO’s control, and possibly screws the rebels altogether, but everyone is happy that the rebels are gone. Even if you think Tomura is capable of that, it’s irrelevant because canon!BNHA has completely different power dynamics. Because Tomura’s violence will always be unpopular and persecuted, rather than justified and glorified by the state, he physically cannot replicate a choice like Hawks’. Tomura can approximate it, but even if he does, he’ll be hunted down by heroes for doing so. The circumstances and consequences for making such a choice are totally different.

So. That’s why I don’t think Tomura and Hawks can be equated. Suggesting that this is a level playing field is essentially believing that criminals and law enforcement exist on level playing fields, and they absolutely do not at all. Hawks is particularly abhorrent because he’s already followed through with his choice. He holds power by being part of the policing class, and regardless of how he came into it, he behaves exactly the same as everyone else who “freely” joined, and in his position of power he made the choice to eliminate someone who was socially powerless.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Drop the essay 🥺 it sounds so interesting

omg I’m so flattered! ❤️ I’ll put it under the cut here (it’s 3600 words lol), just a few things:

Anon is referring to this post

I wrote this for my Gothic Lit + Film module during my BA - 3ish years ago. This clearly isn’t the final version (uncited works, missing bib, etc.) and there’s a lot I would change now. God, I might rewrite it for Victorian Gothic or just for kicks... I got so close to making some really great points lol so forgive Undergraduate me for being almost smart.

And yes, I looked at Interview with The Vampire so #tw: Anne Rice lol

‘Love Never Dies’ (tagline from Bram Stoker’s Dracula)

Explore the Treatment of Homoerotic Desire in Gothic Fiction and/or Film

The Gothic genre is one of transgressions and transformations. It crosses the boundaries of everyday societal norms to explore and express cultural anxieties by reforming psychological worries as physical monsters. Influxes of immigrants from around the Empire and the publication of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution created a huge social shift, undermining religious beliefs of creation and human’s superiority over the natural world. However, it also gave rise to more ‘scientific’ moral categorisations, being twisted to suit the needs of the white colonialists and justify the prejudices of the time by “grounding them in “truth.”” This new Scientia Sexualis, the bringing of sexuality into the psychoanalytic, political and scientific discourse, created new categorisations for sexuality and encouraged identification with these new categorisations.[1] This, for the first time, linked sexuality and identity and now meant one’s sexual practices and preferences came with a “truth” about the person. Homosexuality, as it was now known, was pathologised and seen as a new “species”[2] entirely, one that was a defective, lesser evolution than that of the traditional heterosexuality. Using the Gothic monster meant that authors could explore the ‘queer’ space in society, which means to blur boundaries of sexuality and gender[3] to explore repressed desires and curiosities raised by cultural anxieties over sexuality and gender. In Victorian Gothic, Le Fanu’s Carmilla and Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde are two of examples of using the genre’s transgressive nature and monstrous metaphors to express veiled desires and vicariously act upon them. Although the Gothic gives a home to all that is abhorrent and unacceptable in everyday society, Rice’s Interview with The Vampire explores how the Gothic can treat something on the edge of acceptability. Writing in a time sexual liberation and progressive thinking, Rice’s treatment of homosexuality and non-conventional relationships could be seen to threaten the traditional allegorical use of the genre.

The vampire has long been a sexual being often representing foreign or ‘monstrous’ sex desires and appetites, and Carmilla’s portrayal of aggressive, homoerotic female desire is one the earliest and most complex of these examples. Although one cannot be certain about how progressive Le Fanu wished his novel to be, it can definitely be used to argue against the misogynistic and repressive Victorian gender roles. By using the Gothic genre, Le Fanu explores the ideas of transgressing boundaries, most prominently between life and death, but also using the boundaries of the domestic space being transgressed by Carmilla as a metaphor for the structure of society. The Victorians saw the woman as the ‘angel in the house’, ethereal and asexual, therefore Carmilla’s demonic invasion of the house and her inherently seductive nature is directly antithetical to the socially acceptable version of femininity. However, Carmilla’s “perfidious and beautiful” appearance is confusing for both the other characters, in particular Laura, and the reader themselves. Le Fanu’s expression of female sexuality and gender identity through vampirism conforms to the fact that the “monstrous is transgressive and unnatural because it blends those categories that should be classified as distinct.”[4] Carmilla represents a blurring of the gender boundaries set for women by Victorian society, with vampires being traditionally fluid characters as they “straddle the borders of the living and the dead,” it is natural for Carmilla’s vampirism to give her a freedom akin to that of masculinity. Carmilla excites and threatens the heterosexual male audience with her aggressive sexuality and choice of female victims. On the one hand, she is full of the voracious libidinal energy that is viewed as desirable in sexual objects, but on the other, because of her sexual power and freedom she can be read as a “potential castrator” by becoming a superior sexual predator. Crossing the boundaries of homosocial to homoerotic, Carmilla provides Laura with a relationship separate from her father, one that allows to grow outside of the parameters of the submissive, obedient and asexual daughter. The relationship between Laura and Carmilla means that they have, as Irigaray describes it, “refused to go to market.”[5] The queerness of Carmilla and Laura means that they no longer have to be commodities in the patriarchal market, passed from man to man, but created their own exchange between each other. By engaging in relationship with another woman Carmilla and Laura have “become masculine,”[6] they no longer need to seek masculine assurance outside of themselves or each other.

The group murder of Carmilla by the dominant men in Laura’s life is seen almost identically in Stoker’s Dracula. Lucy is staked by the three men from which she has had blood transfusions in a heavily sexually violent scene where the rebellious female is ‘penetrated’ and subdued by the heterosexual patriarchy. Once Carmilla has been destroyed, Laura is placed safely back under the dominance of the men around her and relies on them to relay Carmilla’s true identity. The confusion between whether they have killed the vampire or the queer woman becomes blurred by Le Fanu here. Laura is told that vampires stalk their victims with the “passion of love” and the use of “artful courtship,”[7]implying that she is not only being warned against vampires, but monstrous queer women. The men in her life invert her homosexual desire into warning signs of a vampire; that she must listen more carefully to the “abhorrence” she feels and ignore the “pleasure” that is akin to the “ardour of a lover.”[8] The novel seemingly ends with the message that many works in the genre embody:

“The Gothic may kill off the monster in such a way as to effect catharsis for the viewer or reader, who sees his or her unacceptable desires enacted vicariously and then safely ‘repressed’ again.”

Carmilla is no exception when it comes to reinstating the status quo after destroying the monstrous queer body it used to be able to safely blur and cross boundaries of societal norms.[9] However, this can also be argued. The novella ends with Laura reminiscing on the time since Carmilla’s destruction, and while she says: “it was long before the terror … subsided”, she also admits there is an “ambiguous” nature to her memories. The male authorities in Laura’s life could see Carmilla’s vampiric nature long before Laura could and despite insisting to Laura that Carmilla was nothing but a “demon”, making it clear that Carmilla’s desire was solely to kill Laura, she still feels affection for her lost friend. The very last sentence of the novella clearly shows her conflicting, but continued desire for Carmilla:

“sometimes the playful, languid, beautiful girl; sometimes the writhing fiend I saw in the ruined church; and often from a reverie I have started, fancying I heard the light step of Carmilla.”

Though the novella is, on the surface, wrapped up neatly with the white, patriarchy dominating over the queer female body, Fanu’s parting sentence emphasises the idea that it might not be a happy ending. Although Carmilla was literallya monster and would have killed Laura had she not been caught, she has clearly had a profound and positive emotional effect on Laura, who was briefly allowed to experience both same-sex support and desire.

Much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were “shadowed by the growing focus on the dangers of … close male friendships and signifiers of homosexuality,”[10] causing a repressed and paranoid time of ‘homosexual panic’. Men of the upper classes moved in almost exclusively male circles; all of their significant relationships outside of marriage would have been homosocial and therefore, plagued with worries about being seen as taking these relationships too far.[11] This paranoia manifested itself in the Gothic literature of the time as frantic and often contradictory.[12] Socially acceptable misogyny allowed male writers to praise homosocial relationships above those with women, who were seen as weak and hysterical, as seen in Stoker’s Dracula when Mina Harker is described as remarkable because she has “the brain of a man.”[13] However, the more insistent and heated misogyny only serves to emphasis what the writers are trying to avoid: being read as homosexual. Stevenson’s novella The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde exemplifies the idea ‘homosexual panic’ manifesting closer to homosexual repression. The invisibility of women, apart from being placed near or as victims of Hyde’s violence, not only speaks to Stevenson’s feelings about women, but also his feelings about men. Hyde’s aggression is often triggered by being faced with female sexuality: he is angered by the prostitute that offers her “venereal box”[14] and the saleswomen that exude “lurid charms” and “coquetry.”[15] While this could be a product of his evilness or lack of moral development, Jekyll retells the former story as the woman offerings a “box of lights,” even though it is clear to both the characters and the readers what really happened. This reluctance to admit to Hyde’s anger towards female sexuality implies an awareness and an anxiety around profound misogyny, particularly if it is female sexuality that repulses Hyde, which leads the reader immediately to ideas of homosexual desire. Through the Gothic genre, Stevenson is able to explore man as “truly two” by creating a physical outlet for this anxiety and repression felt around homosocial relationships that dominated men’s lives. Gothic literature is often full of mystery and secrecy, and like the vampire, which has been linked to the plight of homosexuality because they are forced to live in the shadows, hiding their abhorrent desires and constantly plagued with the fear of being caught and destroyed - Jekyll goes through the same fears with Hyde. Although homosexuality was no long a capital crime (the last men executed for it in the UK being in 1835, the law was changed in 1861, before the publication of both Carmilla (1872) and Jekyll and Hyde (1886)), it was still punishable by law. Jekyll creates Hyde as a criminal outlet for his “concealed pleasures” that he saw as incompatible with his high social status and unworthy of a man respected so greatly by his peers.

Like with the vampire, the Gothic allows for Hyde to be an example of the “monstrous queer” with his “evil” actions reflected in his “deformed” “ape-like” body. In the eighteenth century, ‘monstrous’ was synonymous with queer, linking same-sex desire with the demonic.[16] Similarly, Stevenson’s use of language to describe Hyde is full of natural and evolutionary imagery. He constantly emphasises the fact that Hyde is animalistic, beast-like or, specifically, ape-like to distance Hyde from the respectable and civilised Dr. Jekyll. Hyde is presented as a step down on the evolutionary chain, he is a lesser creature and incapable of higher reasoning and moral thinking. Due to this lack of moral and reasoning capabilities, homosexuals were also seen as inherently selfish and indulgent. The purpose of their sexuality was solely to satisfy personal pleasure rather than transcendental values and contribute to the wider society.[17] This is linked to thinking that Edelman coined as “reproductive futurism,”[18] which is the idea that capitalism’s hold on cultural thinking pervades even to police sexual practices that it deems “unproductive” and therefore, “unnatural.” However, through the Gothic monstrous body, Stevenson can apply natural imagery to Hyde’s impulses and desires while still concealing them under the guise of a “deformity” or a lesser developed being. Through the paradox of his closeness to nature making him ‘abnormal’, Stevenson can tap into the language of the culture and exploit the reader’s psychological justifications for how they view these ‘social disgraces’ (homosexuals), but he can also challenge them.[19] By presenting Hyde as a grotesque Gothic monster the contradictions in viewing homosexuality as both closer to nature and a “deformity” are subtly, but clearly, there for the reader to understand, should they look into the coded meanings of the text.

Anne Rice’s Interview with The Vampire (1976) signalled a new kind a Gothic queer, one living in the age where to identify with homosexuality, personally and socially, was becoming more and more acceptable. One review by Jerry Douglas states that Rice’s series “constitutes as one of the most extended metaphors in modern literature”[20]because it made clear to the mainstream audience the deeply embedded parallel between queerness and the vampire. However, Douglas seems to have missed that almost a century has passed from the first uses of Gothic as an ‘extended metaphor’ for being queer, and it is not the homosexuality that is now hidden in subtext. The homoerotic content of Rice’s novels was so explicitly clear that despite buying the film rights in 1976, impressively the same year as publication, Paramount Pictures did not manage to successfully market the film for production for another twenty years and it was finally released in 1994. Although this proves that society’s view on homosexuality was still decidedly cold and the mainstream audience lacked a palate for viewing homoerotic desire in the cinemas, it also emphasises the leap that Rice was making through her Gothic novels. While homosexuality no longer needed to be coded and staked in a scene reminiscent of gang-rape by white men, the presentation of homoerotic desire and non-conventional relationships still needed the Gothic monstrous body to encourage the audience into a world of blurred boundaries concerning sexuality and gender. One of the revisions for the potential film was to make Louis female, apparently Rice herself offered up this change because she saw it as “consistent with his passivity.”[21] This compromise flags as one of the first indications that Rice’s works may not be the epitome of queer representation in modern Gothic literature, but in fact, she consistently seems afraid to truly obscure and distort societal boundaries of sexuality and gender because of internalised misogyny and homophobia. The film adaptation of Interview with The Vampire, although also written by Rice, downplays the homoerotic content to playful subtext and tension, refusing to risk alienating the mainstream, heterosexual audience by being too transgressive of norms. Coupled with the casting of blockbuster favourites Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise, and Antonio Banderas, whose appeal was deeply entwined with their heterosexuality and masculinity,[22] the novel that was too explicitly queer for the 70s became a cautiously heterosexual-aligned film in the 90s. Perhaps one of the most significant dampeners on the Gothic novel’s queerness and transgression of boundaries was the AIDs crisis, which took hold of western media and created general panic in the 80s. This made the triad of homosexuality, blood, and multiplicity of victims, which appears in the novel, a direct and unavoidable link to the negative misconceptions about and unsympathetic feelings towards AIDs and its victims.