#migrant farmworkers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#immigrants#migrants#migrant farmworkers#trump#immigrant workers#agriculture#florida#vermont#washington#mass deportations

147 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Challenges facing farmers and orchardists relying on the H2-A visa program.

0 notes

Text

headcannon that jasper spoke fluent spanish even before meeting up with alice and the cullens

y'all don't think that man would've picked up on shit while spending a decade or so with maria??

#twilight#jasper hale#he has hella respect for the migrant farmworks in wa#he has esme help set up scholarships and shit for undocumented workers#reparations for being a confederate

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

madelyn very considerately built time into our recording schedule for 'this segment of the recap will probably launch air straight into a five minute digression about labor protections and immigrants' rights' and i am running a mile with the inch she's given me. i'm so sorry madelyn. i have thoughts. and opinions. and sources.

#clenching my fist and going i do not have the time or platform to responsibly or succinctly summarize the impact of DDT on migrant workers#and the intercommunity efforts that went towards the establishment of the EPA and regulations protecting farmworkers from pesticides#especially not in our DATING SIM PODCAST#i point at bustafellows and go he started it

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

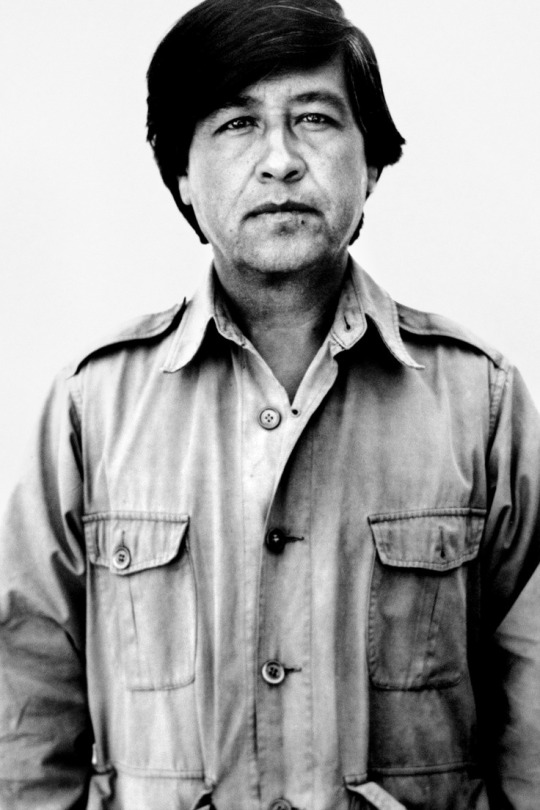

Cesar Chavez grew up on a farm in Yuma, Arizona with his two brothers and two sisters. His family owned a farm and a local grocery store. When Cesar was around eleven years old, hard times from the Great Depression caused his father to lose the farm, so his family packed up all they owned and moved to California to find work. Cesar's family became migrant workers. They moved from farm to farm in California looking for work. All the family members had to work, even Cesar. He worked in all sorts of different fields from grapes to beets, orchards and vineyards. The days were long and the work was very hard. Despite working so hard, the family barely had enough to eat.

Moving so often, Cesar didn't go to school much any more. In just a few short years he had attended thirty-five different schools. The teachers were tough on him. After graduating from the eighth grade, Cesar stopped going to school and the working conditions at the fields for Cesar and his family were horrible. The farmers seldom treated them like people. They had to work long hours with no breaks, there weren't any bathrooms for them, and they didn't have clean water to drink. Anyone who complained was fired.

When Cesar was nineteen he joined the navy, but he left after two years and returned home to marry his sweetheart Helen Fabela in 1948. He worked in the fields for the next few years until he got a job at the Community Service Organization (CSO). At the CSO Cesar worked for the civil rights of Latinos. He worked for the CSO for ten years helping register voters and work for equal rights. Eventually Cesar quit his job in the CSO to start a union of migrant farm workers and he formed the National Farm Workers Association.

One of Cesar's first major actions was to strike against grape farmers. Cesar and sixty-seven workers decided to march to Sacramento, the state capital. It took them several weeks to march the 340 miles. On the way there people joined them. The crowd grew larger and larger until thousands of workers arrived in Sacramento to protest. In the end, the grape growers agreed to many of the worker's conditions and signed a contract with the union. Over the next several decades the union would grow and continue to fight for the rights and working conditions of the migrant farmer.

Born Cesar Estrada Chavez on March 31, 1927 in Yuma, Arizona and died April 23, 1993 in San Luis, Arizona at the age of 66.

#cesar chavez#love#migrants#california#civil rights#farmers#grapes#latino#cso#union#arizona#great depression#strike#human rights#pesticides#mexican#farmworkers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't see a lot of videos on youtube actually interviewing migrant workers, what's up with that?

I might need to go down there to the tours and talk to the workers myself.

0 notes

Text

plus the entire conservative obsession with human trafficking comes from myths of white girls being kidnapped and forced into prostitution across state/national lines that date back to the early 20th-century and that gave rise to the mann act aka "the white-slave trafffic act of 1910," which was then used to prosecute men of color in particular for having consensual sex with white women. the myth of human trafficking exists to stoke reactionary and conservative anxieties and it always has.

the U.S. legal system now largely uses the term "human trafficking" to refer to the exploitation of migrant workers (divided up into "sex trafficking" and "labor trafficking," of which "labor trafficking" is actually more common even though "sex trafficking" wins the greatest political focus b/c of aforementioned white girls being forced into prostitution fears), even though the vast, vast majority of these cases don't involve anyone being forced against their will from one country into another.

as i understand it, the reason it continues to be framed as "human trafficking" in the U.S. even by liberals is basically to get bipartisan support for legislation that conservatives would otherwise be extremely against — e.g., routes to remain in the country for modern slavery survivors like the u/t visas. but this framing is grossly problematic because it perpetuates the myth of "illegal migrants" forcing people back and forth across the border against their will, stoking racist anti-immigration sentiment. and even among people working to support survivors of these exploitative labor conditions, the language of human trafficking exceptionalizes these instances of migrant workers being forced into low/unpaid labor as something uniquely perpetuated by evil "traffickers" rather than resulting from an imperialist economic system that provides little to no labor protections for work done by migrant workers.

a good rule of thumb imo is that if someone is really fixated on 'trafficking' you can safely ignore whatever they have to say like nine times out of ten

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Really wish LibreOffice had like an official app bc I've been editing my resume on a tablet and it's taking fooorreeveerr

#art.txt#yes im job hunting again but i actually have usefull job experience now#and not just retail and migrant farmwork

0 notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Turkey Day everyone!

Today many of us will be enjoying food brought to us by the labor of migrant farm workers. If anyone would like to support the workers who have made our feasting possible I recommend donating to the United Farmworkers Association.

Do not forget the hard working people who have provided us the foods we eat every day. Even if you cannot donate, I recommend keeping these farmworkers in mind.

I also recommend following the UFW on bluesky;

519 notes

·

View notes

Note

I feel compelled to confess that another reason i have a strong reaction to settler western narratives and dust bowl romanticism is because, as a child, i was hopelessly addicted to stallion: spirit of the cimarron.

whether my beloved children's animated horse movie is a motivating factor or the but-for causation of my agitation, I'll let you decide.

Can I ask why you hate Steinbeck? I didn't really like his work either, but it also didn't really inspire any strong emotion in me, so I'm curious about the loathing. Love your analyses and have a nice day!

This was a very lovely message. I'm glad you enjoy my analyses and thank you for the kind words. I'm heinously sleep deprived, but I can't settle because I'm frothing at the mouth over Steinbeck and the Dust Bowl, so maybe providing some context will mollify my seven demons enough to let me rest.

But, I'm drained, so rather than provide any meaningful analysis, I'm going to offer a very brief, broadstrokes, abridged timeline of the Dust Bowl, with emphasis on its historical context, most of which will be haphazardly plucked from myriad sources, which I'll link.

It doesn't capture all, if much of any, of my feelings on the matter, but certainly, it's a snapshot of the bitterest bits.

In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado of Spain became the first European to venture into the Great Plains. He and his expedition were searching for the mythical golden city of Quivira. Instead, they found Kansas.

From 1804-1806, Lewis and Clarke go on an 8,000-mile hike to the Pacific Northwest, harbingering calamity.

The United States of America, drunk on white supremacy, gold in California, religious fervor, and the glut of the Louisiana Purchase, decided it had a divine right to expand westward across North America. In manifesting its destiny, the US leveraged unconscionabile treaties and laws like the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 (along with guns, starvation, and illness) to force many Native Americans to reservations in the West.

From the mid 1850s to the mid 1860s, the West and Plains were struck by a severe drought. This really fucked up the bison, who died in vast numbers.

The Homestead Act of 1862 accelerated the settlement of the western territory by granting land claims in thirty states for a dirt cheap filing fee, five years of sustained residency (after which they could file to recieve proof of ownership), and on the condition that settlers "improve their plot by cultivating the land." These areas were the traditional or treaty lands of many Native American tribes.

Most of those who purchased land under the first Homestead Act were not farmers or laborers and came from areas nearby (Iowans moved to Nebraska, Minnesotans to South Dakota, etc). The act was framed so ambiguously that it seemed to invite fraud, and early modifications by Congress only compounded the problem. Most of the land went to speculators, cattle owners, miners, loggers, and railroads.

Many homesteaders believed that all native peoples were nomads and that only those who owned land would use it efficiently. Few native tribes were truly nomadic. Most nomadic tribes had certain locations they would travel to throughout the year. Other tribes had permanent villages and raised crops. As more settlers arrived, Native Americans were driven farther from their homelands or crowded onto reservations.

Influxes of settlers brought marked changes to the region: bison numbers decreased, fences were erected, domesticated animals increased, water was redirected, non-native crops were planted, unsustainable farming methods increased, and native plants diversity dwindled.

[In 1866, by the way, Congress enacted the Southern Homestead Act to allow poor tenant farmers and sharecroppers in the South to become landowners during Reconstruction. Poor farmers and sharecroppers made up the majority of the Southern population, so the act sold land at a lowered price to decrease poverty among the working class. It was not successful; even the lowered prices and fees were often too expensive. Also, the land made available was mostly undeveloped forestry.]

The late 1870s brought more drought in the Plains. Locusts, which were common to the Plains prior to their sudden extinction, thrived in the drought, ate everything in their path, and ruined crops. The 1875 swarm is estimated to have involved 3.5 trillion insects and covered an area of the West equivalent to the entire area of the mid-Atlantic states and New England. These were the worst swarms during the period of European settlement.

In 1875, Congress passed the Indian Homestead Act to give Native family heads the opportunity to purchase homesteads from unclaimed public lands. This was under the condition that the family head relinquished their tribal identity and relations and, again, "improved" the land. The US government did not issue fee waivers, so many poor non-reservation Natives were unable to pay filing fees to claim homesteads. Those who could pay had difficulty accessing the land because of border disputes due to distance and discord between the US Land Office and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This made white settlements easier to finalize into land ownership.

For the most part, the 1870s drought was followed by a period of wetter than usual conditions that encouraged widespread belief that 'rain follows the plow'. As in, settlers convinced themselves and each other that by cultivating the land using dryfarming crops that needed more water than the Plains could sustainably provide, they could alter its climate, and rains would come.

In 1886, a severe winter killed vast numbers of cattle. This was shortly followed by another severe drought that went on until 1896.

In 1887, Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts decided that Native Americans would prosper if they owned family farms, and his Dawes Act carved reservations into 160-acre allotments. This allowed the federal government to break up tribal lands further. Only those families who accepted an allotment of land could become US citizens. Much of the land subject to the Dawes Act was unsuitable for farming, and large tracts of the allotments were leased to non-Native farmers and ranchers.

After Native American families claimed their allotments, the remaining tribal lands were declared “surplus.” The remaining land was given to non-Native Americans. Land runs allowed the land to be opened to homesteaders on a first-arrival basis.

Unable to catch a hint, the 1880s was a feverish period of settler migration to the West, boosted by both the railroad companies and state and federal governments promising land to those who'd settle it, seemingly without regard for the land's actual carrying capacity.

By the late 1880s, the bison population was thoroughly decimated, meaning the threat of starvation for Native Americans was constant, forcing dependence on the US government and its paltry settlements. Railways, rifles, and an international market for bison hides led to “the Great Slaughter” from about 1820 to 1880, and the bison population plummeted from 30-60 million (estimates vary) to fewer than 1,000 animals. Other factors that contributed to the near-end of the bison: the US military’s directive to destroy bison as a way to control the Native Americans, the introduction of diseases from cattle, drought, and competition from domestic livestock (horses, cattle, sheep).

By the 1890s, drought made clear that the methods of 'dryfarming' used for non-irrigated cultivation of crops, never based on sound science, were wholly inadequate for settling the arid regions of the West. The drought also ended the idea that sturdy settlers, working alone, could manage; the amount of land needed to support even a family was much larger than specified in the Homestead Act but, more crticially, also larger than a family working alone could irrigate. Notably, the 1890s drought was not very dusty, as the Plains were still grassy.

The 1890s drought is partly responsible for the beginning of federally-driven irrigated agriculture with the Reclamation Act of 1902. The act provided for irrigation projects known "reclamation" projects — because irrigation would "reclaim" arid lands for human use. (Unrelatedly, evidence suggests that Native Americans and their precursors may have been in the Plains for at least 38,000 years.)

Theoretically, under the Reclamation Act, the federal government would provide inexpensive water for which farmers would pay, and such payments would then finance the construction of the water projects. The projects' immense construction costs soon proved the premise unrealistic. For example, earlier self-supporting projects created by local initiatives had cost less than twenty dollars an acre. The federal reclamation projects, by contrast, cost an average of eighty-five dollars an acre. Thus, the farmers' share of the federal expenses proved too great a sum for their repayment.

The farmers couldn't pay for their self-sustaining irrigation projects, but Congress extended the repayment periods and continued its irrigation projects. (When repayments still weren't coming in by 1910, Congress advanced $20 million from general treasury funds).

By 1909, most of the prime land in the valleys along the West's rivers had been homesteaded, so to allow dryfarming, which again, the last drought made clear was ill-suited for the arid climate, Congress increased the number of acres for homesteads willing to cultivate lands which could not be easily irrigated. There was a wet period, so the soil was fertile, and settlers, who were still immigrating to the Plains in droves, understood that to mean they were right, rain followed the plow, so they plowed the shit out of it.

In the 1910s, the price of wheat rose, and then, with the onset of the Great War, so did demand for wheat in Europe. So, the settlers plowed up millions of acres of native grassland to plant wheat, corn, and other row crops—still on marginal lands that could not be easily irrigated, even with Congress's pretty dams in every river.

In the 1920s, the war had ended, so the demand for American wheat dropped, and the post-Great War recession sank prices. But, it was also the dawn of tractors and farming mechanization, so settlers went in together on machines they couldn't afford to produce wheat fewer people wanted on land too submarginal to sustain it, and tore that grass up with the wild abandon (like, literally, they abandoned soil conservation practices) of transplants who didn't know anything about the grasslands they were ecologically devastating.

Grasslands, by the way, are fertile because when grasses die, their roots die too, and then their roots decay and fertilize the topsoil into rich earth, which nourishes the other grasses—a self sustaining cycle of life and death. Grasses also have extensive root systems that bind soil particles together, improving soil structure and preventing erosion. Soil erosion occurs when soil is exposed to the impact of wind and water, detaching and transporting soil particles, eventually deteriorating the soil's fertility. Soil erosion can also become dangerous when soil is swept downstream and becomes heavy layers of sediment that disrupt water flow and suffocate aquatic flora or when tossed by the wind so that suspended particles cloud the air, eyes, and lungs.

The Great Plains is the windiest region in North America, namedly because of the airstreams coming down from the Rockies to the West, the shifting pattern of the jet stream in upper levels of the atmosphere, and the fronts of warmer, moist air masses moving in from the Gulf of Mexico to the southeast entangling with the cooler, drier air moving southward from Canada and the Arctic.

Between 1925 and 1930, settlers plowed more than 5 million acres of previously unfarmed land, stripping the soil of its native grasses to expand their fields.

In 1929, overspeculation, excessive bank loans, agricultural overproduction, and panic selling (among other things) caused the US stock market to have a kitten hissy fit, kickstarting the Great Depression.

In 1930, the first of four major drought episodes began in the Plains.

In 1931, despite the lower demand, the settlers leveraged mechanized farming to produce a record crop. This flooded the market with wheat that no one could afford to buy. So, settlers couldn't make back their production costs, so they expanded their fields to try and produce more to make a profit, planting wheat or leaving unused soil bare.

The unanchored soil that was once rich, biological earth became friable, and was swept by high winds into apocalyptic dust storms.

In 1932, the US authorized federal aid to the drought-affected states, and the first funds marked specifically for drought relief were released in the fall of 1933.

[In 1933, Congress created the Tennessee River Valley (TVA). The TVA, under the banner of a sweeping mandate from Congress to promote the "economic and social wellbeing" of the people living in the river basin, decided that too many Southerners were living on the land. From 1933 to 1945, TVA sought to solve the South's economic problems by seizing 1.3 million acres from Southerners and displacing an estimated 82,000 people, many of them illiterate and impoverished, from their homes in order to build 16 hydroelectric dams. They flooded valleys where people once lived.]

[In 1938, President Roosevelt addressed the Conference on the Economic Conditions of the South: "No purpose is closer to my heart at this moment than that which caused me to call you to Washington. That purpose is to obtain a statement—or, perhaps, I should say a re-statement as of today—of the economic conditions of the South, a picture of the South in relation to the rest of the country, in order that we may do something about it: in order that we may not only carry forward the work that has been begun toward the rehabilitation of the South, but that the program of such work may be expanded in the directions that this new presentation will indicate."]

By 1940, 2.5 million people had moved out of the Plains states; of those, 200,000 moved to California. They were not met warmly, and their lives in California were as difficult as the ones they'd left in the Plains, with approximately 40% of migrant farmers winding up in San Joaquin Valley, picking grapes and cotten.

[The Dust Bowl migrant farmers took up the work of Mexican migrant workers, 120,000 of whom were deported from San Jaoquin Valley during the Mexican Repatriation — which refers to the repatriation, deportation, and expulsion of Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the United States during the Great Depression between 1929 and 1939. Estimates of how many were repatriated, deported, or expelled range from 300,000 to 2 million (of which 40–60% were citizens of the United States, overwhelmingly children).]

John Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath in 1939, in which he invokes the harshness of the Great Depression and arouses sympathy for the struggles of [some] migrant farm workers. He's praised as having "masterfully depicted the struggle to retain dignity and to preserve the family in the face of disaster, adversity, and vast, impersonal commercial influences." He based the novel on his visits to the migrant camps and tent cities of the workers, seeing firsthand the horrible living conditions of migrant families—

[—and, quite possibly, Sanora Babb's Whose Names Are Unknown, which was written in the 1930s but not published until 2004, since Random House cancelled its publication after The Grapes of Wrath was released in 1939. Babb had moved to California in 1929 to take a job at the Los Angeles Times. When she arrived, the stock market had crashed, the Great Depression had begun, and the promised job dried up. A migrant without a home, she slept in a city park before leaving for Oklahoma in the mid-1930s, where she witnessed the terrible poverty gripping her native state. Eventually, she returned to California to work for the FSA, serving migrant families stranded without a home or a job, just as she had been years earlier. In contrast, John Steinbeck gained much of his understanding of Great Depression conditions in Oklahoma second hand, through reading reports by federal aid workers like Babb and Collins and from his experience delivering food and aid to California migrants from the Southern Plains. The two novels share strikingly similar imagery, so if you enjoyed The Grapes of Wrath, you'll likely also enjoy Whose Names Are Unknown.]

The Grapes of Wrath won the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962.

[Steinbeck scholar David M. Wrobel wrote that "the John Steinbeck/Sanora Babb story sounds like a classic smash-and-grab: celebrated California author steals the material of unknown Oklahoma writer, resulting in his financial success and her failure to get her work published...Steinbeck absorbed field information from many sources, primarily Tom Collins and Eric H. Thomsen, regional director of the federal migrant camp program in California, who accompanied Steinbeck on missions of mercy...if Steinbeck read Babb’s extensive notes as carefully as he did the reports of Collins, he would certainly have found them useful. His interaction with Collins and Thomsen — and their influence on the writing of The Grapes of Wrath — is documented because Steinbeck acknowledged both. Sanora Babb went unmentioned."]

Writer Timothy Egan calls the Dust Bowl, "a classic tale of human beings pushing too hard against nature, and nature pushing back."

[To justify itself to Congress and the American public, TVA painted a dim picture of the farms it was going to flood and residents of the South. In films, books, and speeches, TVA pointed to poor farming practices and erosion as the chief culprits in the region’s poverty. Poverty and environmental problems in the South had more to do with lumber and mining industries, which extracted natural resources before abandoning the mountains. But TVA depicted the valleys as “wasted land, wasted people,” as if Southern farmers themselves were to blame.]

When Eleanor Roosevelt visited California in 1940 and saw squatter camps and the model government camps and was asked by a reporter if The Grapes of Wrath was exaggerated, she answered unequivocally, “I never have thought The Grapes of Wrath was exaggerated.” Steinbeck wrote to thank her for remarks: “I have been called a liar so constantly that sometimes I wonder whether I may not have dreamed the things I saw and heard in the period of my research.”

[With a budget in the tens of millions of dollars, TVA devoted just $8,000 and 13 staffers to resettlement efforts. Almost as many tenants as landowners were evicted by TVA, and for this class of “adversely affected” farmers, the agency assumed even less obligation. “It is the very necessity of the tenants having to go which will make them find their own solution to their difficulties,” wrote one TVA staff member.]

Anyway, no, I don't like Steinbeck, and I don't enjoy reading about the Dust Bowl.

[Damning the Valley by Wayne Moore, America's Forgotten History Of Mexican-American 'Repatriation' an interview with Francisco Balderrama]

#sarah just indulged me in rewatching it because this post sparked a craving in me#and then sincerely engaged and discussed and analyzed its subtleties with me#even after i sent her an 8 page journal essay on it to further discuss#anyway.#also please dont take the above too seriously#my beloved childhood animated horse movie is woven into the fabric of my being and worldview#but i am from the deep south. i knew about what tva did from oral history & it is sincerely hard for even me to find very many sources on i#that and the violence against native americans and the way dust bowl romanticism erases it from a narrative#despite being THE causation and lesson and consequence that should overwhelmingly frame how we talk about the dust bowl#and just the gaudy way that poor white migrant farmworkers are symbologized in dust bowl lit and reflections#without any actual class justice or extrapolation or contextualization#and the racism in tva and its approaches and how black southerners were disproportionately targeted & impacted#(which i didnt even get into in this post)#are obviously the raison d'etre#but it's also important that i ask myself: how much IS this deeply ingrained bias i have for this movie#itself oversimplified and complicit and romanticist and escapist with regard to the above narrative#leeching into why i feel the way I do about this specific event (especially since I don't have acute & immediate ties to it)#because i can't say it hasnt unconsciously and consciously influenced me and my knee jerk reactions#so while i also dont think i could actually quantify it#or that it's a mortal sin or net bad thing to have a children's story steer me towards scrutinizing a historical mythos#metacognition is vital to comprehension and self awareness and thus our impact on and responsibilities wrt our own histories

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

that exploitation comment on your massage post reminded me of when i posted a picture of people harvesting lettuce and someone said it was weird to share pictures of immigrant farmworkers who were being exploited.

I was like hey actually those are my classmates and community members on a local organic farm and you just said that bc we are all latino. thank you and fuck off 😍

Yeah! Spot the white saviour complex at 20 paces. One of those "so desperate to prove you aren't racist that you became racist" things lol.

Like, don't get me wrong, it's a legitimate concern to hold, but as I said, to state it as absolute fact based on absolutely nothing but Vibes really makes it clear that they (a) have the instincts of a white saviour swerf and (b) are primarily motivated by getting to feel self-righteous rather than actually reducing harm. If they wanted to genuinely help, the comment would have been "I worry there's a risk that this place might be exploiting migrants, as many are. Have you seen or noticed any indicators?" And, you know, maybe a list of such indicators.

Eh. Ah well. We don't need to like each other.

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

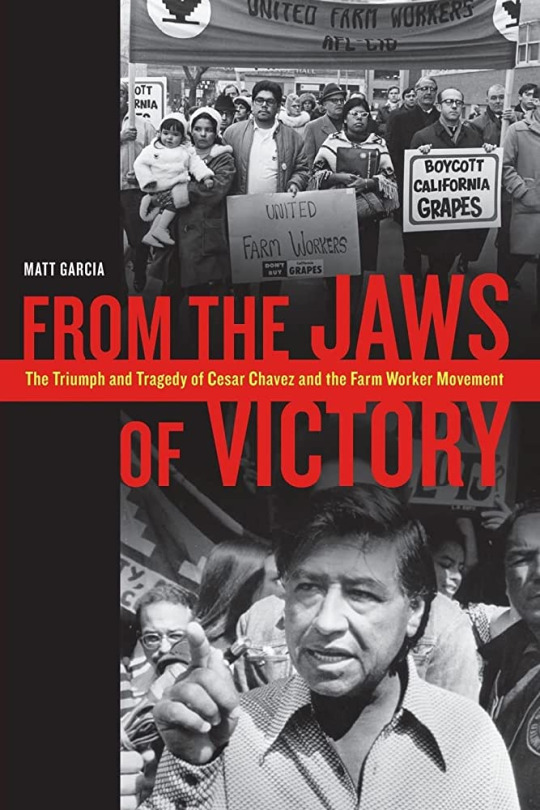

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

#history#u.s history#labor history#ufw#united farm workers#cesar chavez#dolores huerta#trade unions#social history#social movements#unions

70 notes

·

View notes

Link

I’ll never forget something that advocate and former farmworker Leticia Zavala said to me during an interview.

“There is slavery in the fields of North Carolina.”

She said it almost in passing, as part of a larger laundry list of abusive and deadly conditions experienced by farmworkers in the state as part of the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program, a guest worker program overseen by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that allows American employers to temporarily hire migrant workers to perform agricultural work. A whopping 90% of these workers hail from Mexico. This is not surprising, given that the H-2A program is an iteration of the Bracero Program, a bilateral agreement with Mexico that, from 1942 to 1964, allowed for the temporary entry of millions of migrants to perform agricultural labor in the U.S. The program was ultimately abolished because of systemic wage theft, abuse, and exploitation. Lee G. Williams, the DOL official in charge at the time, described the Bracero Program as “legalized slavery.”

As a farmworker organizer, Zavala sees it all: the toll that backbreaking and dangerous agricultural labor takes on workers, the substandard and unhealthy living conditions they are forced to endure, the labor trafficking, starvation, and the all-too-common stolen wages. And there’s also the “modern-day slavery.” Along with other preferred euphemisms used in agriculture—forced labor, involuntary servitude, and indentured servitude—“modern-day slavery” simply means slavery that is happening now, today, the results of which can be found in the produce aisles of countless American grocery stores.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

-fae

140 notes

·

View notes

Link

Last year, during the hottest summer on record, Angel and hundreds of other workers on Dearnsdale fruit farm in Staffordshire were told to pick and sort about 100-150kg of strawberries every day inside polytunnels designed to trap heat. It was so hot that at least one worker fainted, she said. The strawberries they picked ended up on the shelves of some of the UK’s largest supermarkets, including Tesco, Co-op and Lidl.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and VICE World News has uncovered widespread mistreatment of migrants working at more than 20 UK farms, nurseries and packhouses in 2022. Workers reported a litany of problems, from not going to the toilet for fear of not hitting targets, to being made to work in gale-force winds. Some said they would be shouted at or punished for having their mobile in their pocket or talking to work colleagues while on the field. Others said they were threatened by recruiters with being deported or blacklisted.

Many were left in debt and destitution, and some left the UK being owed money by their employers. One worker even had to pull out his own tooth because he could not find appropriate medical care. Our findings expose a poorly enforced government visa scheme that is flagrantly breached by farms and recruiters, and which leaves people vulnerable to exploitation.

At Dearnsdale, those who made mistakes or failed to hit targets were routinely sanctioned. The most common punishment was to have their shift cut short – every day several workers would be sent back to their caravans after only a few hours’ work. That meant that on a day when a worker was hoping to earn money for eight hours of work, they would be paid for only three. The practice is common on farms using the visa scheme.

For workers like Angel, who took on debt to pay for visas and flights to come to the UK, having their earnings cut was devastating. Even after picking fruit and vegetables for five months, she still has not been able to pay off her £1,250 loan.

[...]

Human rights experts and lawyers say that the design of the UK seasonal worker visa puts workers at an increased risk of exploitation. Because these visas tie migrants to their sponsor, a recruiter, workers are then unable to seek work with anyone else, even if they have problems with their employer or their recruiter stops offering them work.

Workers are not only dependent on their recruiter and the farm employing them for work, but also for their housing, transportation and even information about their employment rights. Workers who are this dependent on their employer can find it harder to leave exploitative situations.

193 notes

·

View notes