#metropolitan museum of art (1981)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Model Sporting Boat

Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, ca. 1981-1975 BC. Tomb of Meketre (TT280), Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 20.3.6

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress

1780

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

"This separate bodice and ankle-length skirt stand out from within the first waves of radical change in fashion in the late 1770s, for the horizontal separation of parts and the exposure of the feet. Such practical thinking--with primary reference to peasant traditions, not to elite clothing--was still combined with panniers and a conical silhouette of past practice. But, most significantly, a dialogue has begun: clothing can be changed by real needs, even the desire of women to be active, to walk more in nature (as advocated by Rousseau) and stand less on ceremony. In the 1981-82 Costume Institute exhibition "The Eighteenth-Century Woman," this costume was worn with an enormous wig with a frigate atop it, in the manner of court celebrations of French naval victories. But this dress had already taken its own plebeian and pedestrian path and should not be mistaken with the last flourishes of court hegemony."

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Model of a shield and quiver with javelins, Egypt, Middle Kingdom circa 1981-1802 BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lintel of Amenemhat I and Deities

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egyptian Art Collection

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 108

Period: Middle Kingdom

Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Reign: reign of Amenemhat I–Senwosret I

Date: ca. 1981–1952 B.C.

Geography: From Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht North, Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, MMA excavations, 1907

Medium: Limestone, paint

Dimensions: H. 36.8 × W. 172.7 × D. 13.3 cm, 183.7 kg (14 1/2 × 68 × 5 1/4 in., 405 lb.)

Accession Number: 08.200.5

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue Quilted Silk Robe à la Française, ca. 1750, European.

Met Museum.

#blue#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#robe à la française#1750#1750s#1750s dress#1750s extant garment#met museum

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Purse. ca. 1760. Credit line: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Designated Purchase Fund, 1981 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/156992

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptian model boat (painted wood) belonging to one Ukhhotep. Artist unknown; ca. 1981-1802 BCE (12th Dynasty, Middle Kingdom). Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#art#art history#ancient art#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#model#boat model#woodwork#carving#12th Dynasty#Middle Kingdom#Metropolitan Museum of Art

385 notes

·

View notes

Photo

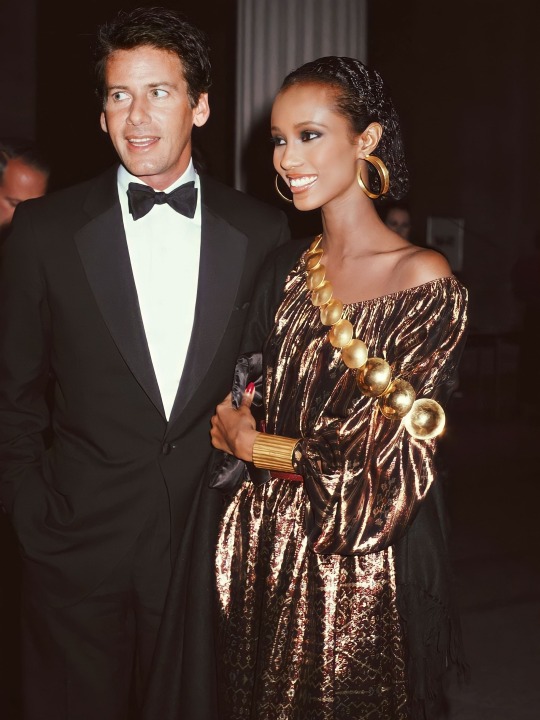

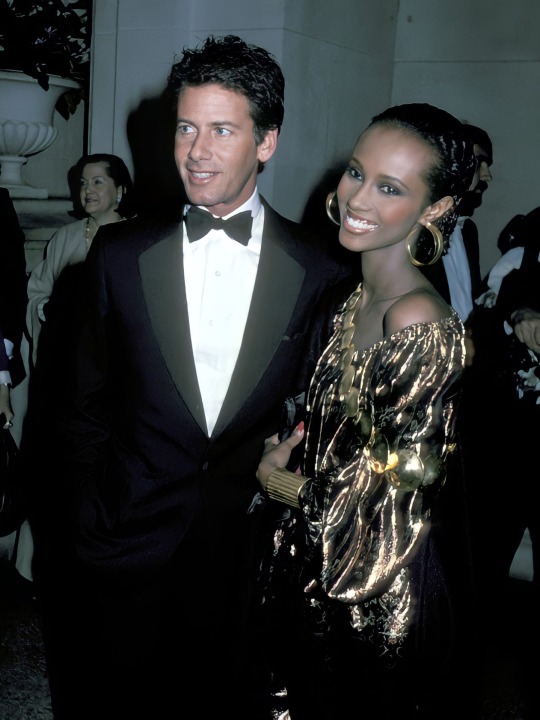

Iman with Calvin Klein photographed by Ron Galella at the Eighteenth-Century Woman exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute (December 1981). This was Iman's first Met Gala.

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

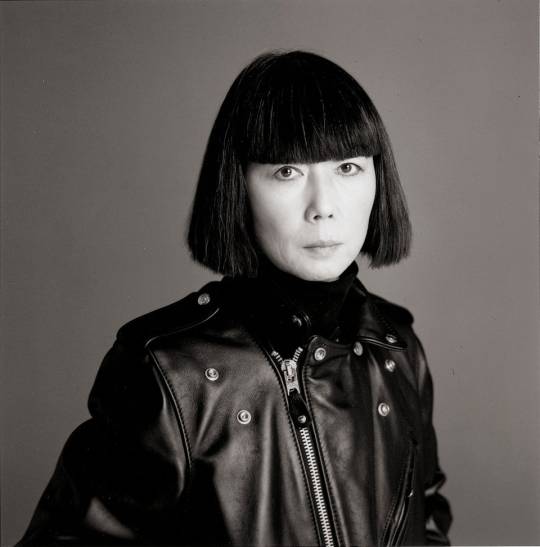

Rei Kawakubo ( 川久保 玲) is a Japanese avant-gardist of few words, and she changed women’s fashion.

Kawakubo was born in 1942 in Tokio, three years before the atomic bombs landed on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She studied the history of aesthetics—both Japanese and Western—at Keio University, worked in advertising for a spell at a textile company, and then started working as a freelance stylist in 1967. Kawakubo opened her first office in Paris and staged her first Comme des Garçons ("Comme des garçons” means “like some boys), show there in 1981. Not surprisingly, one of her favorite themes is punk, which was waking up the world to the principles of individual choice and just-do-it spirit just as her brand was finding its feet. Her conceptual clothes, mostly black and often tattered with holes, were an affront to the sexy, body-conscious fashions of the time—such as Mugler and Montana. But over the course of the '80s, Kawakubo's intellectual and feminist take on fashion often mirrored the cultural and emotional turmoil of women infiltrating the male-dominated work world. It also began to influence a new generation of designers

Being one of fashion's most influential designers, Rei Kawakubo strives to challenge the form the traditional garment. Kawakubo is the second living designer to be honored for an exhibition at the Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This Comme des Garçons exhibition in particular highlights key themes that have inspired and continue to inspire her creativity as a designer.In the context of the human form, the body is radically reconsidered. She proposes new ideas of beauty by creating organic forms and protrusions in her garments, creating outfits that discard standard sizes. An example of an exhibition in which she radically questions form is her spring/summer 1997 collection, known as "Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body". Through this exhibition Kawakubo is targeting body modification through dress, generating unstructured dresses and forms that don't highlight on erogenous zones of the body. By doing this, she is also questioning ideas surrounding gender and the body creating transgressive forms, discarding stereotypes surrounding the female.

Kawakubo’s clothes may have the rigor of modernist architecture but there are loose flaps, extraneous arms, and asymmetrical edges that let the wearer improvise her own particular style of dress. It is not rare to see shredded dresses, blood-red hoods, or large bulges protruding from odd places on the “Comme” runway. The clothes look like they are designed to reject description, indeed, they seem to be deliberately constructed to confuse and repel bystanders. This act of rebellion may come off as shock theater, but it actually offers something much more compelling: distance that allows for self-expression. In avoiding trends and convention, Kawakubo’s clothes embody a clear mantra: when others do not understand you, they are unable to define you. Ultimately, it is up to you to define yourself, be it through your clothes or the things that you say. Dressing for yourself, as opposed to dressing to make others comfortable, is an act of freedom that only fashion can offer.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Usuyuki by Jasper Johns. 1981. American.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#Usuyuki#art#culture#history#modern history#modern art#jasper johns#abstract#american art#America#american history#the metropolitan#the metropolitan museum of art#the Met

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Additional Readings on it all, both popular and academic - An ‘Ism’ Overview - Perspectives Comparing And contrasting art movements

Prehistoric Art:

Palaeolithic Art (40,000 BCE - 10,000 BCE)

Clottes, Jean. Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times. University of Utah Press, 2003.

Guthrie, Dale. The Nature of Paleolithic Art. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Vanhaeren, Marian, et al. "Middle Paleolithic shell beads in Israel and Algeria." Science, vol. 312, no. 5781, 2006, pp. 1785-1788.

Marshack, Alexander. "Upper Paleolithic notation and symbol: a provisional framework." Man, vol. 16, no. 1, 1981, pp. 95-122.

Neolithic Art (10,000 BCE - 2,000 BCE)

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul G. Bahn. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. 7th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Hodder, Ian. The Leopard's Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Catalhoyuk. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2006.

Whittle, Alasdair, and Vicki Cummings. "Going over: People and things in the early Neolithic." Proceedings of the British Academy 144 (2007): 33-58.

Soffer, Olga. "The Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic in the Russian Plain: Problems of Continuity and Discontinuity." Journal of World Prehistory 4, no. 4 (1990): 377-426.

Ancient Art:

Egyptian Art (3100 BCE - 30 BCE)

Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Robins, Gay. The Art of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press, 2008.

Freed, Rita E. “The Representation of Women in Egyptian Art.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 81, 1995, pp. 67-86.

Redford, Donald B. “The Heretic King and the Concept of the ‘Golden Age’ in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 33, no. 4, 1974, pp. 365-371.

Greek Art (800 BCE - 146 BCE)

Boardman, John. The Oxford History of Greek Art. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Pollitt, J. J. Art and Experience in Classical Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1972.

Neer, Richard T. "The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture." American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 105, no. 2, 2001, pp. 255-280.

Osborne, Robin. "Greek Art in the Archaic Period." The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 115, 1995, pp. 118-131.

Roman Art (509 BCE - 476 CE)

Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015.

Brilliant, Richard. Roman Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Kleiner, Diana E. E. "Roman Sculpture." Oxford Art Journal 26, no. 1 (2003): 49-63.

Stewart, Peter. "The Social History of Roman Art." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 7, no. 1 (1997): 83-96.

Medieval Art:

Early Christian Art (200 CE - 500 CE)

Robin Margaret Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (New York: Routledge, 2000).

William Tronzo, The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014)

Herbert Kessler, "The Spiritual Matrix of Early Christian Art," Representations, no. 11 (1985): 96-119, doi:10.2307/2928505.

Jas' Elsner, "What Do We Want Early Christian Art to Be?" Religion Compass 2, no. 6 (2008): 1118-1138, doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00091.x.

Byzantine Art (330 CE - 1453 CE)

Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Mango, Cyril. The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453: Sources and Documents. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

Mango, Cyril. "Byzantine Architecture." The Grove Dictionary of Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 19, 2023. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000002606.

Evans, Helen C. "Byzantium and the West: The Reception of Byzantine Artistic Culture in Medieval Europe." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 4 (Spring, 2001): 3-44. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3269056.

Islamic Art (7th century CE - present)

Grabar, Oleg. Islamic Art and Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Bloom, Jonathan M. and Sheila S. Blair. Islamic Arts. London: Phaidon Press, 1997.

Blair, Sheila S. "The Mosque and Its Early Development." Muqarnas 10 (1993): 1-19.

Carboni, Stefano. "The Arts of Islam." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 4, 2001, pp. 5-6, 17-65.

Romanesque Art (11th century - 12th century)

Conrad Rudolph, "Artistic Change at St-Denis: Abbot Suger's Program and the Early Twelfth-Century Controversy over Art," (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

George Henderson, "Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque," (London: Thames & Hudson, 1972).

C. R. Dodwell, "The Dream of Charlemagne," The Burlington Magazine 118, no. 875 (1976): 330-341.

Gerardo Boto Varela, "The Iconography of the Lamb and the Role of the Temple in the Creation of the Romanesque Architectural Sculpture in the Kingdom of León," Gesta 43, no. 2 (2004): 171-186.

Gothic Art (12th century - 15th century)

Camille, Michael. Gothic Art: Glorious Visions. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Conrad Rudolph. Artistic Change at St-Denis: Abbot Suger's Program and the Early Twelfth-Century Controversy over Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Kemp, Simon. "The Uses of Antiquity in Gothic Revival Architecture." The Art Bulletin 73, no. 3 (1991): 405-421.

Snyder, James. "Gothic Sculpture in America: The Late 19th Century." The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 34, no. 4 (1975): 286-304.

Renaissance and Baroque Art:

Renaissance Art (14th century - 17th century)

Gardner, Helen, et al. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History. 16th ed., Cengage Learning, 2019.

Greenblatt, Stephen. Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare. University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Baxandall, Michael. "The Period Eye." Renaissance Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1987, pp. 3-20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24409669.

Freedberg, David. "Painting and the Counter Reformation." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 32, 1969, pp. 244-262. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/750844.

Mannerism (1520 - 1580)

Freedberg, S. J. (1993). Painting in Italy, 1500-1600. Yale University Press.

Shearman, J. (1967). Mannerism. Penguin Books.

Cole, B. (1990). Virtue and magnificence: Leonardo's portrait of Beatrice d'Este. Artibus et historiae, 11(21), 39-58.

Baxandall, M. (1965). "Il concetto del ritmo" in Michelangelo's Entombment. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 28, 9-29.

Baroque Art (1600 - 1750)

Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. 16th ed. Phaidon Press, 1995.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art and Architecture. 2nd ed. Laurence King Publishing, 2005.

Haskell, Francis. "The Judgment of Solomon: Poussin's 'The Sacrament of Ordination' and the Critics." The Burlington Magazine, vol. 124, no. 948, 1982, pp. 275-284.

Brown, Jonathan. "The Golden Age of Dutch Art: Painting, Sculpture, Decorative Art." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 64, no. 4, 2007, pp. 36-44.

Rococo (1715 - 1774)

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, The Spiritual Rococo: Décor and Divinity from the Salons of Paris to the Missions of Patagonia, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Alastair Laing, ed., Rococo: Art and Design in Hogarth's England, exh. cat. (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984).

Alina Payne, "Fragile Alliances: Rococo and the Enlightenment," Art Bulletin 85, no. 3 (2003): 540-564.

Melissa Lee Hyde, "Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century," Journal of Design History 21, no. 3 (2008): 219-23

19th Century Art:

Neoclassicism (1750 - 1850)

Wölfflin, Heinrich. Principles of Art History. Translated by M. D. Hottinger, Dover Publications, 1932.

Rosenblum, Robert. Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art. Princeton University Press, 1967.

Praz, Mario. "The Eighteenth-Century Elegiac Mood: Some Clarifications and Distinctions." Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 2, no. 3, 1969, pp. 295-318.

Honour, Hugh. "The Ideal of the Classic in the Visual Arts." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 22, no. 1/2, 1959, pp. 1-25.

Romanticism (1800 - 1850)

Abrams, M. H. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1971.

Bloom, Harold. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. Oxford University Press, 1973.

Frye, Northrop. "Towards Defining an Age of Sensibility." Studies in Romanticism, vol. 1, no. 1, 1962, pp. 1-14.

Mellor, Anne K. "Possessed by Love: The Female Gothic and the Romance Plot." PMLA, vol. 102, no. 2, 1987, pp. 134-150.

Realism (1830 - 1870)

Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Walt, Stephen M. The Origins of Alliances. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987.

Waltz, Kenneth N. "The Theory of International Politics." International Security 15, no. 1 (Summer 1990): 5-17.

Morgenthau, Hans J. "Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace." Foreign Affairs 28, no. 4 (July 1950): 566-583.

Impressionism (1860 - 1900)

Herbert, Robert L. Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

Moffett, Charles S. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.

Smith, Paul. "Monet's Impressionism: Aesthetic and Ideological Dilemmas." The Art Bulletin 68, no. 4 (1986): 595-615.

Dumas, Ann, and Anne Distel. "Monet at Vetheuil: The Turning Point." The Burlington Magazine 124, no. 953 (1982): 350-58.

Post-Impressionism (1886 - 1905)

Paul Smith, ed., "Post-Impressionism" (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1988).

Richard R. Brettell, "Post-Impressionists" (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

John House, "Post-Impressionism: Origins and Practice" in "Oxford Art Journal" vol. 6, no. 2 (1983): 3-16.

Patricia Mainardi, "The End of Post-Impressionism" in "Art Journal" vol. 43, no. 4 (1983): 308-313.

20th Century Art:

Fauvism (1900 - 1910)

Elderfield, John. Fauvism. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1976.

Shanes, Eric. The Fauves: The Reign of Color. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995.

Hargrove, June. "Matisse, Fauvism, and the Rediscovery of Pure Color." The Art Bulletin 63, no. 4 (1981): 689-704.

Rewald, John. "The Fauve Landscape." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 79, no. 6 (1972): 287-304.

Cubism (1907 - 1914)

Cooper, Douglas. The Cubist Epoch. Phaidon Press, 1970.

Green, Christopher. Cubism and its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916-1928. Yale University Press, 1987.

Shiff, Richard. "Cézanne and the End of Impressionism: A Study of the Theory, Technique, and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art." The Art Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 4, 1976, pp. 529-555.

Barr, Alfred H. "Cubism and Abstract Art." The Museum of Modern Art Bulletin, vol. 1, no. 3, 1934, pp. 6-7.

Futurism (1909 - 1916)

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. Futurist Manifestos. Edited by Umbro Apollonio, translated by Robert Brain and Others, Thames and Hudson, 1973.

Leighten, Patricia. Futurism: An Anthology. Yale University Press, 2019.

Perloff, Marjorie. "Futurism's 'Futuricity'." Modernism/modernity, vol. 19, no. 2, 2012, pp. 247-263.

Santoro, Marco. "The Politics of Speed: Futurism and Fascism." The Journal of Modern History, vol. 87, no. 4, 2015, pp. 821-856.

Dadaism (1916 - 1924)

Hulsenbeck, Richard. Dada Almanach. Berlin: Erich Reiss, 1920.

Gale, Matthew. Dada & Surrealism. London: Phaidon, 1997.

Naumann, Francis M. "Dada and the Concept of Art." The Art Bulletin 69, no. 4 (1987): 634-651. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3051041.

Dadoun, Roger. "The Dada Effect: An Anti-Aesthetic and its Influence." October 66 (1993): 3-16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/778760.

Surrealism (1920 - 1940)

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Ades, Dawn. Dada and Surrealism Reviewed. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978.

Martin, Alyce Mahon. "Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War." Oxford Art Journal 20, no. 2 (1997): 77-89.

Weisberg, Gabriel P. "Surrealism in America: The Beginning." Art Journal 28, no. 3 (1969): 222-29.

Abstract Expressionism (1940 - 1960)

Greenberg, Clement. Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, 1961.

Rosenberg, Harold. The Tradition of the New. New York: Horizon Press, 1959.

Alloway, Lawrence. "Networks, Names and Numbers." Artforum 1, no. 2 (1962): 29-33.

Hess, Thomas B. "Abstract Expressionism." Art News 51, no. 9 (1952): 22-23, 45-46, 48-49.

Pop Art (1950s - 1960s)

Foster, Hal. The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha. Princeton University Press, 2012.

Livingstone, Marco, ed. Pop Art: A Continuing History. Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Alloway, Lawrence. “The Arts and the Mass Media.” Architectural Design and the Arts and Crafts Movement, vol. 31, no. 9, 1961, pp. 346–349. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4228719.

Lippard, Lucy R. “Pop Art.” Art International, vol. 12, no. 8, 1968, pp. 24–31. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24889088.

Minimalism (1960s - 1970s)

Judd, Donald. Complete Writings, 1959-1975. New York: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975.

Fried, Michael. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Lippard, Lucy. "Eccentric Abstraction." Art International, vol. 12, no. 2, 1968, pp. 24-27.

Krauss, Rosalind. "Sculpture in the Expanded Field." October, vol. 8, 1979, pp. 30-44.

Conceptual Art (1960s - 1970s)

Kosuth, Joseph. Art after Philosophy and After: Collected Writings, 1966-1990. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

Lippard, Lucy R. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions.” October 55 (Winter 1990): 105-143.

Graham, Dan. “The End of Liberalism.” In Dan Graham: Rock My Religion. Edited by Brian Wallis, 31-59. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Performance Art (1970s - present)

Abramovic, Marina. The Artist Is Present: Essays. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Goldberg, RoseLee. "Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present." October 56 (1991): 78-89.

Jones, Amelia. "Presence in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation." Art Journal 56, no. 4 (1997): 11-18.

Postmodernism (1970s - present)

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Lyotard, Jean-Francois. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Butler, Judith. "Contingent Foundations: Feminism and the Question of ‘Postmodernism’." The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 86, no. 10, 1989, pp. 571- 577.

Harvey, David. "The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change." Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1990.

Digital Art (1980s - present)

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

Christiane Paul, Digital Art, (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008).

Sarah Cook and Beryl Graham, "From Periphery to Centre: Locating the Technological in Art History," Art History 28, no. 4 (September 2005): 514-536, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2005.00442.x.

Oliver Grau, "The Complexities of Digital Art," in MediaArtHistories, ed. Oliver Grau (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 45-67.

Street Art (1980s - present)

Chaffee, Lyman, and Chris Stain. Walls of Heritage, Walls of Pride: African American Murals. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

Harrington, Steven. Street Art San Francisco: Mission Muralismo. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2009.

Schacter, Rafael. "The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 73, no. 4 (2015): 385-387.

Riccini, Raffaele. "Street Art as a New Form of Urban Governance: A Comparative Perspective." Urban Affairs Review 52, no. 5 (2016): 723-746.

Contemporary Art:

Neo-Expressionism (1980s - 1990s)

Storr, Robert. 1986. "Dislocations: Themes and Meanings in Post-World War II Art." New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Harrison, Charles, and Paul Wood. 1991. "Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas." Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Bois, Yve-Alain. 1986. "Painting: The Task of Mourning." October 37 (Summer): 15-63.

Krauss, Rosalind E. 1985. "The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths." Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Installation Art (1990s - present)

Bishop, Claire. Installation Art: A Critical History. New York: Routledge, 2005.

O'Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Schneider, Rebecca. "The Explicit Body in Performance." TDR: The Drama Review 46, no. 2 (2002): 74-91. doi:10.1162/105420402320980586.

Bishop, Claire. "Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics." October 110 (2004): 51-79. doi:10.1162/0162287042379787.

Relational Aesthetics (1990s - present)

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 1998.

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso, 2012.

O'Doherty, Brian. "Inside the White Cube." Artforum 5, no. 1 (1967): 12-16.

Bishop, Claire. "Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics." October 110 (2004): 51-79.

New Media Art (1990s - present)

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Paul, Christiane. Digital Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Gere, Charlie. "Digital Culture." In The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis, 491-506. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Drucker, Johanna. "The Century of Artists' Books." Art Journal 56, no. 3 (1997): 20-34.

Superflat (1990s - present)

Murakami, Takashi. Superflat. New York: MADRA Publishing, 2000.

Schimmel, Paul. Color and Form: The Geometric Sculptures of Donald Judd. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1991.

Krajewski, Sara. "Superflat and the Politics of Postmodernism." Postmodern Culture 14, no. 3 (2004): 1-18. doi:10.1353/pmc.2004.0046.

Nakamura, Lisa. "Cuteness as Japan's Millennial Aesthetic." Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65, no. 2 (2007): 137-147. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2007.00207.x.

Post-Internet Art (2000s - present)

Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012).

Karen Archey and Robin Peckham (eds.), Art Post-Internet: INFORMATION/DATA (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014).

Gene McHugh, "Post-Internet: Art After the Internet," Artforum International 52, no. 1 (2013): 366-71.

Nora N. Khan and Steven Warwick, "Fear Indexing the X-Files," e-flux Journal 56 (2014): 1-9.

Afrofuturism (2000s - present)

Sheree R. Thomas, ed., "Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora" (New York: Aspect/Warner Books, 2000).

Ytasha L. Womack, "Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture" (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013).

Nettrice R. Gaskins, "Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Aesthetics," "Journal of Black Studies" 40, no. 4 (2010): 699-710.

Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones, "Introduction: The Rise of the Afrofuturist," "Black Magnolias Journal" 5, no. 2 (2018): 1-11.

Socially Engaged Art (2000s - present)

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso, 2012.

Kester, Grant. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Kester, Grant. "Dialogical Aesthetics: A Critical Framework for Littoral Art." in Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985. Ed. by Simon Leung. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

Thompson, Nato. "Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011." Art Journal, Vol. 71, No. 1, 2012, pp. 101-102.

Environmental Art (2000s - present)

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

Kastner, Jeffrey, and Brian Wallis, eds. Land and Environmental Art. London: Phaidon, 1998.

Kagan, Sacha. "The Nature of Environmental Art." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 51, no. 3 (1993): 455-67.

White, Edward. "Earthworks and Beyond." Art Journal 39, no. 4 (1980): 326-32.

NFT Art (2010s - present)

Belamy, Christies. (2018). Portrait of Edmond de Belamy. Paris: Obvious Art.

Harrison, P., & Weng, S. (2021). The NFT Bible: Everything you need to know about non-fungible tokens. United States: Independently published.

Liu, Z., Wang, J., & Lin, L. (2021). From NFT to NFA: The Implications of Blockchain for Contemporary Art. Journal of Cultural Economics, 45(2), 245-264. doi: 10.1007/s10824-021-09421-6

Schellekens, M., & Zuidervaart, H. (2022). On the Importance of Being Unique: An Analysis of Non-Fungible Tokens as a Medium for Digital Art. Leonardo, 55(1), 56-63. doi: 10.1162/leon_a_02179

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Relief of Amenemhat I

The king wears a tightly curled wig, with an uraeus cobra on his brow to protect him from his enemies, and the false beard of kingship. He carries a flail, also a symbol of his rule, and a ceremonial instrument known as a mekes.

The first king of 12th Dynasty, Amenemhat I is known to have been born in the south of Egypt, and may have served as vizier to the last ruler of the previous dynasty, Mentuhotep IV. Early in his reign, he moved the capital from Thebes to a new city in the north, Itj-tawy. In order to ensure the stability of his new dynasty, he also appears to have established a coregency with his son, Senusret I, ten years before his demise.

Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, ca. 1981-1952 BC. From Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, Lisht. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 08.200.5

Read more

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

In case anyone wanted to know what I was basing Theo's yellow coat on - this is what I picture.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collage, I like destruction (name is still in progress, much like the rest of the piece) made using

Augustus of Prima Porta, unknown (1 ad)

The Wedding at Cana, Paolo Veronese (1562-1563)

Ciphers and Constellations, in love with a woman (1941)

Jeff Koon, Lobster (2003)

Untitled (Cala Lilies) - Donald Sultan 1998

Charioteer of Delphi - INIOCHOS - 470 to 478 BC

Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump - Jean-Michel Basquiat - 1982

Head (1981) Jean-Michel Basquiat

Marble Statue of Aphrodite - Roman Imperial - the metropolitan Museum of Art

ludovosi Ares - Lysippos - 4th Century BCE

Winged Victory - unknown sculptor - 4th century BC

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egyptian Art Collection

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 105

Period: Middle Kingdom

Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Reign: reign of Amenemhat I, early

Date: ca. 1981–1975 B.C.

Geography: From Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Southern Asasif, Tomb of Meketre (TT 280, MMA 1101), serdab, MMA excavations, 1920

Medium: Wood, gesso, paint, linen

Dimensions: l. 73 cm (28 3/4 in); w. 55 cm (21 5/8 in); h. 29 cm (11 7/16 in) average height of figures: 21 cm (8 1/4 in.)

Credit Line: Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920

Accession Number: 20.3.12

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow Silk Robe à la Polonaise, 1780-1785, American.

Met Museum.

#met museum#yellow#silk#dress#robe à la polonaise#18th century#1780#1780s#American#USA#womenswear#extant garments#1780s usa#fave#1781#1782#1783#1784#1785

182 notes

·

View notes