#maybe its the new yorker in me but people feel so entitled to how other people live their lives but ITS NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS SO STFU

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

okay no im not done bc when i was about 5ish years old, i was diagnosed with OCD, it's still on my chart to this day. i spent the majority of my childhood thinking i had "a weird kind of OCD" as my dad called it. he said i obviously had the same kind he had because i acted just like him and that his doctors told him it was a "rare form of OCD" he'd forgotten the name of. i don't have OCD. not a rare kind or any other kind. but i am autistic.

i'll put the full story under the cut but basically

tl;dr- stop talking about professional diagnosis as if it's the only true way to know if someone actually has the disorder. professionals are wrong all the fucking time, actually + getting a misdiagnosis can be so much worse than not having a professional diagnosis at all.

for about half my life, i remember sitting up at night, wondering why i was the way i was. why i am the way i am. even after receiving my diagnoses (the others aren't important rn), i couldn't understand myself at all. i tried researching OCD as best as a small child can but most help for OCD is aimed towards adults, not children, and none of them talked about the specific things i struggled with the most. i thought i was broken

it wasn't until i was 15 years old when i was talking to my latest therapist (at the time) and she asked me to explain my diagnoses and how they affect me that my entire world would slowly start to change. i told her about all of my symptoms of OCD and she asked me why i do those things, no one had ever asked me that before so i explained it to her.

and she tilted her head, the confusion growing on her face the longer i talked and when i finished, i'll never forget what she said. "that doesn't sound like OCD.. those aren't the motivations behind OCD and that's probably why trying to help you with it hasn't worked. you don't have it. it sounds, to me, like you have autism spectrum disorder." and as a teenager with a passion for psychology, i was, at first, insulted at the idea that i could have been so wrong about myself and got angry.

once i calmed down i realised that despite my raging 15 year old ego, i had never actually looked into OCD in-depth, just surface level stuff when i was a little kid. so i decided to delve more into it and found that she was right, both the DSM-5 and stories from people with OCD didn't lign up with my experiences very much when looked at beyond the surface level. so i decided to do some more in-depth research into autism, which spiralled into very in-depth research into autism, which spiralled into an identity crisis lasting years.

so after literal years of denial before eventually coming to terms with being misdiagnosed and having misunderstood everything about myself for the majority of my life at that point, at 19 years old, i sought out a legitimate diagnosis. i found a psychologist and simply told him everything i told had told the therapist, all the things i had thought were because of OCD, but this time explaining my thought process behind each one and also all the other things i struggled with that the Advice For Adults With OCD books and blogs never mentioned like my difficulties with social situations.

then, this licensed medical professional said to me, "well you've described asperger's perfectly.. but i don't think you have it because autistic people don't know there's anything wrong with them"

he, then, went on to say that i'm obviously "too smart to be autistic" and to "just get a tutor to help with the social anxiety". he went on and on about how i don't look autistic and i'm so good at verbalising so i just can't be autistic. i really hope i don't need to explain how that's ableist as fuck for anyone to say, let alone a medical professional. also. asperger's was not considered a valid diagnosis at this point in time so literally nothing he said has any basis in science whatsoever. in fact, if you read the criteria for level one autism, it actually explicitly states that the person may not appear outwardly autistic as sometimes the symptoms present more inwards.

do you understand why people don't want to seek a professional diagnosis? i was told point blank that i had literally described "asperger's" (now classified as level one autism) to a fucking T and was still refused a diagnosis for the crime of being able to understand that i struggle to function in a world not designed for me and articulate those struggles to someone who's job is supposed to be to help me.

i chose not to seek a diagnosis after that. i do not wish to ever have autism on my records whatsoever. i do not want to ever face a situation where i have an autism diagnosis on my record and i meet another doctor like that psychologist, who will see that and assume that i am incapable of thinking for myself or to refuse me autonomy, using my diagnosis as grounds to say that i don't understand the gravity of my own choices. i have heard many horror stories of doctors refusing to listen to diagnosed autistics or take them seriously. the american psychiatric system is actively harmful and violent towards disabled people.

in fact, i do not care for the psychiatric system in america whatsoever, i do not respect professional diagnoses as having anymore credit than well-researched self diagnoses. i do not blindly trust that any mental health "professionals" are actually knowledgeable in their field until they prove themselves to be. i have faced far too many who would frequently tell me, when i was in my teens, that i should be a therapist or a psychologist because i was teaching them things. that's not a brag btw because that's not a fucking good thing. if your 14 year old client is frequently teaching you things, you aren't doing enough research into your own field. this is not a testament to my intelligence, it's a testament to their incompetence.

people who get so hung up about being "professionally diagnosed" are so funny to me bc they have clearly never had to deal with having been misdiagnosed & the genuine stress (+ potential trauma) that can come from it

like oh, so you think medical professionals are infallible? do you really, genuinely think that doctors have zero biases? especially against certain diagnoses? especially against women and minorities? you don't think there's a severe lack of research for the majority of the population despite the fact that the majority of medical research is done on white cis men?

trying to get a diagnosis in order to get help for a disability can be incredibly difficult to begin with due to the stigma of being disabled. so i really need yall to understand that if you do manage to get a diagnosis and it turns out that it's wrong, the best case scenario is that it's going to make getting the help you need much harder while you continue to struggle with whatever disability you actually have and wondering why nothing helps for however long it takes for you discover to that you were misdiagnosed (if you ever do) & tell a doctor who might believe you and might give you the proper treatment.. if you're really, really lucky

#tw ableism#systematic ableism#people need to learn how to mind their own business#maybe its the new yorker in me but people feel so entitled to how other people live their lives but ITS NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS SO STFU#it actually pisses me tf off like why hasnt anyone punched u in the mouth yet

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

An unlikely thing happened to me on my two weeks’ off. I watched an HBO Max miniseries that mocked some aspects of wokeness.

Mike White’s “The White Lotus” is a tragicomic exposé of our current moneyed elites and the psychological dysfunction they labor so mightily under. There’s a blithe, unthinking finance jock, with a worked-out bod, an uneasy new wife, and a shitload of money, who can muster misery at the slightest ruffle in perfection. There’s the beta male, married to the mega-rich corporate CEO wife, worried about the condition his balls. There’s the super-uptight gay manager, hanging on to sobriety, as he performs for his clients; the mega-wealthy, overweight lost soul, played by Jennifer Coolidge, whose life is a pampered abyss of emotional desolation; and an aspiring young journalist who reconciles herself to money and indolence over a mindless career of clickbait snark.

…

And the most repellent characters are two elite-college sophomores, Olivia and Paula, packed to the gills with the fathomlessly entitled smugness that is beginning to typify the first generation re-programmed by critical theory fanatics. You watch as they casually abuse and denigrate their brother — a young man consumed by living online; you see how they mock anyone who doesn’t meet their exacting standards of youth or beauty; you watch them betray and lie to each other; you see them condescend to someone still struggling to pay back student loans (see the clip above); and you witness the co-ed of color, Paula, act out her antiracist principles, with disastrous real world results for a Hawaiian she thinks she is saving from oppression. She leaves her wreckage behind, gliding away, with impunity, to another semester of battling racism.

At one point, in a memorable scene, as the white daughter expounds about the evil of white straight men, her mother points out that she is actually talking about her brother, sitting at the same table. An individual person. Right next to her. Someone she might even love, if such a thing were within her capacity. Someone who cannot be reduced to a demonized version of his unchosen race and heterosexuality. And the only character one can bond with, and root for, is indeed this young white American male, awkward but genuine, whose story ends with a new bond with his dad, an escape from online addiction, and a newly revitalized human life.

“The White Lotus” is not an anti-woke jeremiad. It’s much subtler than that. Even the sophomores seem more naïve and callow than actively sexist and racist. The miniseries doesn’t look away from the staggering social inequality we now live in; and gives us a classic white, straight, male, rich narcissist in the finance jock. But it’s humane. It sees the unique drama of the individual and how that can never be reduced to categories or classes or identities.

And this step toward humaneness is what interests me. Because if we can’t intellectually engage people on how critical theory is palpably wrong in its view of the world, we can sure show how brutal and callous it is — and must definitionally be — toward individual human beings in the pursuit of utopia. “The White Lotus” is thereby a liberal work of complexity and art.

…

Applebaum’s Atlantic piece is a good sign from a magazine that hired and quickly purged a writer for wrong think, and once held a town meeting auto-da-fé to decide which writers they would permanently anathematize as moral lepers.

Similarly, it was quite a shock to read in The New Yorker a fair and empathetic profile of an academic geneticist, Kathryn Paige Harden, who acknowledges a role for genetics in social outcomes. It helps that Harden is, like Freddie DeBoer, on the left; and the piece is strewn with insinuations that other writers on genetics, like Charles Murray, deny that the environment plays a part in outcomes as well (when it is clear to anyone who can read that this is grotesquely untrue). But if the readers of The New Yorker need to be fed distortions about some on the right in order for them to consider the unavoidable emergence of “polygenic scores” for humans, with their vast political and ethical implications, then that’s a step forward.

…

And then, in the better-late-than-never category, The Economist, the bible for the corporate elite, has just come out unapologetically against the Successor Ideology, and in favor of liberalism. This matters, it seems to me, because among the most zealous of the new Puritans are the boards and HR departments of major corporations, which are dedicated right now to enforcing the largest intentional program of systemic race and sex discrimination in living memory. Money quote: “Progressives replace the liberal emphasis on tolerance and choice with a focus on compulsion and power. Classical liberals conceded that your freedom to swing your fist stops where my nose begins. Today’s progressives argue that your freedom to express your opinions stops where my feelings begin.”

The Economist also pinpoints the core tenets of CRT in language easy to understand: “a belief that any disparities between racial groups are evidence of structural racism; that the norms of free speech, individualism and universalism which pretend to be progressive are really camouflage for this discrimination; and that injustice will persist until systems of language and privilege are dismantled.” These “systems of language and privilege” are — surprise! — freedom of speech and economic liberty. If major corporations begin to understand that, they may reconsider their adoption of a half-baked racialized Marxism as good management. Maybe that might persuade Google not to mandate indoctrination in ideas such as the notion being silent on questions of race is “covert white supremacy,” a few notches below lynching.

…

And then there’s a purely anecdotal reflection, to be taken for no more than that: all summer, I’ve been struck by how many people, mostly complete strangers, have come up to me and told me some horror story of an unjust firing, a workplace they’re afraid to speak in, a colleague who has used antiracism for purely vindictive or careerist purposes, or a hiring policy so crudely racist it beggars belief. The toll is mounting. And the anger is growing. The fury at CRT in high schools continues to roil school board meetings across the country. Some Americans are not taking this new illiberalism on the chin.

This isn’t much, I know. Read Peter Boghossian’s resignation letter from Portland State University to see how deep the rot has gotten. But it’s something. It’s a sign that there is now some distance from the moral panic of mid-2020 and the start of reflection upon the most zealous aspects of this new illiberalism.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorites 19

Helado Negro. “And we’ll light our lives on fire just to see if anyone will come rescue what left of me.”

LISTEN: Sofi Tukker: Ringless Jamila Woods: Basquiat Big Thief: Century Helado Negro: Please Won’t Please Kota the Friend: Hollywood Joan Shelley: Teal Big Thief: Not Anderson .Paak: Jet Black Twain: Run Wild Dori Freeman: That’s How I Feel Angie McMahon: Slow Mover The New Pornographers: Higher Beams Rob Curly: Faded Sampa the Great: Any Day Cataldo: Ding Dong Scrambled Eggs Lloyd Cole: Violins Mark Mulcahy: Happy Boat Amber Mark: Mixer J. S. Ondara: Saying Goodbye Cuco: Bossa No Sé Tyler Lyle: Marina Karaoke The Japanese House: Follow My Girl

Here we sit between the final holiday of this year and the first holiday of the next one. Again, I am attempting to encapsulate my past 365 days of cultural consumption in a post. It feels more difficult this time around. Not because I enjoyed less. Quite the opposite. I feel the past year brought such varied creative stimuli that I struggled to recall much of it. That said I’ll let this flow and ask permission for an addendum, usually worked back into the overall recap in appropriate places, this year simply attached to the end. But before the beginning of the next one.

I’m going to dive headfirst into the record I easily spun more than any other this year, perhaps several years – Helado Negro’s This is How You Smile. Working creatively under the name Helado Negro, Roberto Carlos Lange is a musician of Ecuadorian decent working across genres and languages. I became aware of his work for the first time in 2011 with his release of Canta Lechuza. Reading reviews and listening to tracks I felt conceptually kindred to the work but for whatever reason the songs themselves did not resonate with me. In 2019 when This is How You Smile was released I curiously read a review that mentioned the title’s referencing a work by Jamaica Kincaid. Kincaid’s story Girl first appeared in the New Yorker in 1978. The work is accessible and brief so I read it before listening to one note of the record. When I finally did, I was transfixed. It is the kind of work I wanted to share with anyone who would listen, even texting friends about it at inappropriately early morning hours as I listened; Justin would love this; This is right in Venessa’s wheelhouse, my sister, old friend from college I hadn’t spoken to since his divorce this is a good reason to reconnect. The funny thing is it’s not a record that is inclined to draw people in right away. It’s not built on irresistible hooks or propolsive beats. It unfolds quietly across simple but lush instrumentation, drifting back and forth between English and Spanish, often in the same song. “Running,” the first single, is as unassuming as a track can be. Languid and gentle it practically intends to lull the listener to sleep.

In June I drove with Mrs. OhBoy across two states to see Lange perform with a stripped-down two-piece band at the always wonderful Grog Shop in Cleveland. Knowing my sister lived within shouting distance I invited her to join us. The band played the new record in its entirety front to back. I’m not usually a fan of this live show format but Lange worked it magically. A lighting issue kept the stage darkener than intended for the first few tracks. When it was finally rectified the band and the audience all decided we preferred the previous illumination and the lights were dimmed again. Sometimes songs ended cleanly and abruptly. Sometimes saxophones or digital loops made it impossible to mark when one song ended and the other was beginning. The room seemed to shimmer with each note and gentle phrasing. When the set wrapped, I asked my fellow attendees their thoughts. Mrs. OhBoy summed up my total experience with the work of Helado Negro beginning with Canta Lucheza through his newest, at first, I wasn’t sure but then I thought ‘oh I get it.’

The second and third records I consumed with voracity this year are the tandem from Big Thief, U.F.O.F. and Two Hands. This quartet is working at the top of their game. And work they do. I had the pleasure of seeing them performed in 2018 at the Voodoo Music Festival in New Orleans. Nearing the end of their set Andrianne Lenker announced it was to be their last live performance of a perpetual two-year tour during which they had released two records. They took only the smallest of respites from touring recording and releasing both U.F.O.F. and Two Hands. They seem to be constanly creating. The Beetles played 292 shows at the Cavern Nightclub in Hamburg – Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours rule – how do you get to Carnegie Hall? - and in July of this year I speculated Big Thief to be the best band in America. Watching the four piece perform you get the sense that they could finish each others sentences but are just as likely to let each other ramble on for hours.

There are countless clips of the band playing live that make my case but I’m fond of this intimate little performance.

Speaking of musical acts improving on themselves with each release, this year brought a new e.p. from the duo Sofi Tukker. Nothing about this infectious act fits with the rest of my musical tastes. But how am I supposed to quit them if they keep putting out records like Dancing on the People. The integration of rock-oriented guitar licks and the multi-cultural cross pollination keep the musical arrangements from falling into rote dance patterns. And on “Ringless” Sophie Hawley-Weld composes lyrical quality akin to Stephin Merritt - “I'm more than the worst thing I've ever done. I’m less than the best thing I've ever won.”

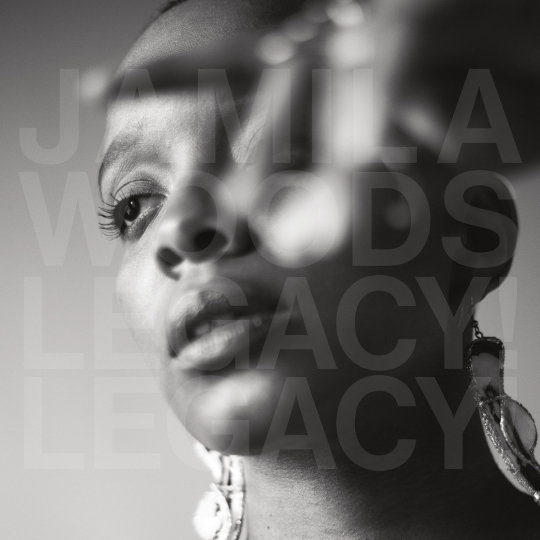

Earlier this month NPR’s Ann Powers published a fascinating piece, Songs That Bend Time. Featured in the article-playlist combination is Chicago’s own Jamila Woods. And rightly so considering her latest release is entitled Legacy! Legacy! and each track pays homage to pioneers that Woods admires. The entire record is astonishing in both composition and performance. “Basquiat” is a great place to start.

It seems I am perennially placing Joan Shelley on my yearly favorites list but truthfully, she was absent last year. 2019 brought Like the River Loves the Sea, another lilting work with her frequent collaborators Nathan Salsburg, James Elkington and Will Oldham. Recorded in Iceland where, as Joan tells it, they were unable to find a banjo anywhere, the record wonderfully utilizes the angelic violin and cello work of Þórdís Gerður Jónsdóttir and Sigrún Kristbjörg Jónsdóttir. Teal and The Fading are true standouts in a solid lineup of Shelley compositions.

“Hollywood” by Kota the Friend was my unofficial song of summer. And two of my long-time heroes, Lloyd Cole and Mark Mulcahy notably had their best records in a turn. Mulcahy brings us The Gus and finds him pushing his story telling prowess to new heights. The track “Late for the Box” treads onto George Saunders level observations. Cole’s Guesswork reunites him with Commotions partner Blair Cowen and effortlessly blends some of Lloyds previous electronic instrumental work with his more noteworthy singer songwriters’ efforts. It feels retro and current at the same time. Similarly, “Higher Beams” from The New Pornographers latest effort, The Morse Code of Brake Lights is as close to a new 70’s-era Genesis song as we may ever hear again.

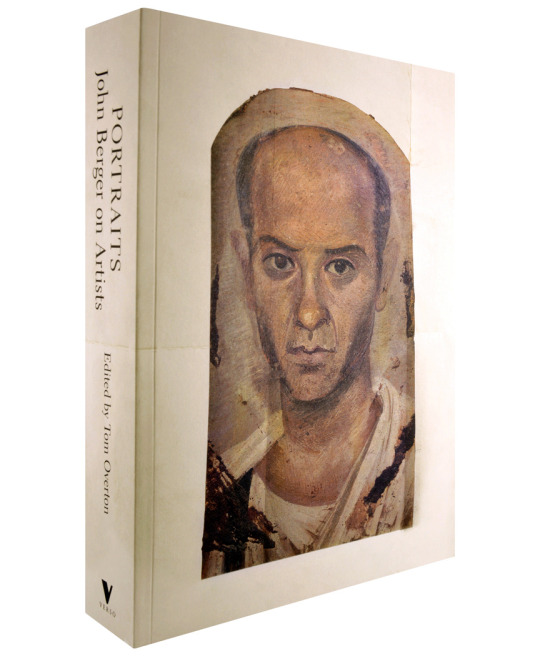

I was able to carve out a little more time for reading in 2019 than previous years. Not a lot but enough to keep multiple books going at once. I haven’t been able to maintain such a practice before. Maybe I grew into it. Or more likely the specifics books I chose allowed for it. I’ve been making my way through John Berger’s Portraits form nearly two years. Its structure is pefect for picking up, putting down and then picking up again. I cannot imagine another person writing more eloquently on the experience of humans creating and interacting with visual art. His writing is cerebral but not lofty. His language is precise yet textural. In a way I hope never to finish this book.

I haven’t read much George Saunders, only Civilwarland in Bad Decline, but when I finally opened Lincoln in the Bardo I poured through it. It can be a difficult read at first. But like Helado Negro, once I caught on to what the artist was doing (oh, I get it), every word was a joy.

Superheroes and deep mythologies are not my cup of tea, but Watchmen is fantastic. To be honest we have their final episode yet to view. We are cherishing it in a way we had previously with the final episode of Catastrophe. The writing is clever and complex. The performances are so good that one cannot imagine any other actor playing any of the roles – Jean Smart? Wow!

Counter to Watchmen, although there is certainly an aspect of mythology, is Lodge 49. AMC has announced they are not renewing it, so we hope it finds a new home. What is so unique about this set of characters and their tales is how ultimately low the stakes are, yet how much the viewer is compelled to care.

I have not seen Parasite yet although it is on the list for this week. We don’t go to the theater a lot, but we did go to see Knives Out. Pure fun. I wore a broad smile for the final 15 minutes of this caper. A fantastic ensemble and masterfully woven story. Not to the lcomplexitiy of the time-jumping Watchmen, much more immediate with the stakes made clear early. That’s what makes this a fresh take on an old genre.

So, here’s the forewarned addendum. One of the books I’ve juggled since Thanksgiving was recommended to me by a friend upon our adopting a new dog, an English Setter. My friend is an avid outdoorsman and has had two retrievers since I’ve known him. Both of the dogs were impeccably trained and behaved which is always important, but can be especially so for larger and active breeds. He told me he used a book called Water Dog to train his retrievers. It is an old book written by Richard A. Wolters and published in 1964. And the bulk of it, as the title suggests, has to do with teaching a dog to retrieve ducks for hunters. Wolters is wry and no-nonsense from the opening paragraph. He threads scientific data with gut instinct and acknowledges that some of his views may be questionable, but his results speak for themselves. Addressing the theory that you’ll ruin a hunting dog by keeping it inside the house with the family, Wolters proposes it was “thought up by some old house wife who hated dogs.” To be sure I am not recommending this because of the results it has brought us with our new four-legged family member. I have only just begun utilizing the books techniques. And as the largest percentage of them relate to laying in a blind and waiting for fowl to approach, be shot and then retrieved, I will never use most of it. But I have read every word, never thinking that a hunting dog manual would be a book that I joyfully balanced in the mix of everything else I intended to experience this year.

*Update (or addendum 2?): We watched the final episode of Watchmen. Go directly to HBO now. Do not pass Go. Do not collect $200. It is mind-bendingly entertaining and provocative. And yet I hope they make not another second of it. It’s not possible to match the quality of these nine episodes.

Under the wire musical addendum. The Japanese House: “Follow MY Girl”

I almost forgot about this gem of a record. Good at Falling came our way back in March. Running the last errands of the year (dog treats to keep pups occupied during a pajama clad New Year’s Day) the randomizer in Apple Music reminded me. So glad it did. And that I prepped this space for late entries. Happy New Year. .

0 notes

Text

They All Saw a Cat

Last week, I was innocently skimming through Emily Nussbaum’s New Yorker commentary on the Girls series finale. I stopped watching this show a while ago—I liked it, and much of the material in early seasons resonated with me, but to a point. That point, or points, were Adam, the whiplashiest character I’ve ever hate-love-hated, forcing himself on his girlfriend and then Hannah repeatedly assaulting her ear with a q-tip. But I digress. I’ve followed the cultural zeitgeist of the show and Lena Dunham herself, and I like Emily Nussbaum, so I read the review. (You can, too.)

Somewhere in the middle of the piece, in a parenthetical no less, Nussbaum asserts: (You can’t be a writer without being entitled: Why else would you think anyone wants to listen to you?)

Record scratch. Oh, god. Is that possibly possibly true? Or rather, are any of the components that make up this doozy of a declaration? Because she’s saying 1) all writers are entitled, and 2) that the act of writing is synonymous with the belief that anyone wants to listen to us, and 3) that that unanimous and inherent entitlement is the reason why we believe that anyone wants to listen to us.

Before I put “Delete blog/set book(s) on fire” on my to-do list, I paused to think.

Couldn’t this (horrible! faulty!) logic be applied to anyone who ever created anything? A chef, or a painter, or, as my tech-minded husband said testily, “How about all the people in the world who feel sure that their app is the one that needs to be made?”

I admit, I spent five years of my life working at a nonprofit that encourages hundreds of thousands of people annually that they have a story (or perhaps dozens) to tell. This nonprofit has been likened more than once to a new breed of parent that believes and convinces their child that he or she is a special snowflake unlike any other, and is capable of—and dare I say it, entitled to--anything he or she sets his magical little mind to. (I am parent to a nine-month-old snowflake myself, and understand how terribly, seductively easy it is to adopt this mindset. No judgement here!)

I’m not now, nor was I ever, saying we’re all Pulitzer-quality yarn-spinners (Nussbaum actually is), but I genuinely do believe that we all have stories to tell that are unlike the stories that anyone else can tell. No one is exactly the same, and while that doesn’t imbue their differences with magic or the right to special treatment, it does add value to their perspective. This perspective allows each of us to experience, understand, live, and do everything differently from each other, and it also makes that uniqueness of experience unknowable to anyone else. That is, unless we decide to share it. And how do we share it, but by telling stories. That story could be painted, plated, coded, thrown on a wheel and fired in a kiln, or knit from dog hair into a dog sweater. Making something out of nothing is telling a story of some kind.

This storytelling isn’t new, btw. We are not talking about a tool for millennials to message each other disappearing videos, or broadcast their every location or opinion or achievement to the masses. People have been telling stories from the very beginning, with words and hieroglyphs and inventions and yes, novels and essays and, now, blogs and critiques and columns.

I am tickled by the thought that anyone ever looked at a cave painting drawn by one of our earliest ancestors and thought, “That entitled sonofabitch.” Maybe they did! Totally their right to feel that way, too.

As part of this snowflake-producing creative writing nonprofit, NaNoWriMo utilized the horrible, useful, sometime hilarious millennial tool for storytelling (and searching and archiving), the hashtag, specifically for a campaign called #whyIwrite (about, you guessed it, why you/I/anyone writes). I did a quick search (thanks, hashtags!) and not a single person wrote “Because I am entitled.” (But then who, other than Emily Nussbaum, is that self-aware? I’m looking at you, caveman.) My quick-search also turned up what I and my cohorts had to say on the subject back in 2011.

“I write because so many things are better read than said. Misunderstandings are too easy in spoken communication; we talk so much and so fast and with so many interruptions! Writing is a haven where I may sit with a concept, clarifying here and editing there, until I can stand back and say, “Here. This is exactly what I mean.””

Reading this makes me realize, I guess, that I’ve gone and made a leap of my own. I am operating on the (possibly gross/horrible/faulty) logic that to write is to tell a story of some kind. And while my above answer does address why I *write* my stories instead of, for example, saying them out loud or painting them (can’t) or cooking them (sometimes I do that, too), or coding them (nope), it doesn’t ask or address exactly why I tell stories (aka create anything, written or otherwise) in the first place.

We’ll get to that in a sec, though.

Do you remember the study showing that by reading literary fiction, we humans’ emotional sensitivity is improved? The NYTimes characterized the findings thusly:

“…after reading literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction or serious nonfiction, people performed better on tests measuring empathy, social perception and emotional intelligence — skills that come in especially handy when you are trying to read someone’s body language or gauge what they might be thinking.”

I don’t know what middling impact or nonimpact my nonserious nonfiction (as opposed to its serious counterparts, or literary or popular fiction) might have or not have but… this is #whyitellstories. My stories happen to be true stories, and they’re not always mine, and so I have no idea if any of it increases or promotes understanding in this often baffling and misunderstood world. If not this way, though, how else will we gain any insight into what’s happening elsewhere to other people of other belief systems and capabilities and ethnicities and everything else that makes up our own snowflakey identities?

I’m not writing to be read, or telling stories to be heard or listened to. The writing-down part is ultimately a selfish act; a putting together of disparate pieces to make something comprehensible in times of confusion. I am using the written word to make sense of, well, everything. So why do I share it? Why tell the story instead of logging it away, sussed but otherwise unconsumed? In the hopes that maybe I’m not alone in my wonderings or bafflement. That anyone else who ever felt confused or amazed or humbled or edified might see the way it happened over here, through this lens of experience, and might think that even though it was different for them, maybe it was also the same.

Even though I think hope Emily Nussbaum is wrong, there’s more than enough room for her opinion and perspective and… were we to meet over a Cinnabon or a tub of hummus, she may come to believe I am the wrong one, indeed the most entitled nonserious-nonfiction writer she ever did meet. We’re probably both right. And wrong. And there is plenty of room for both versions or some combination therein.

As I am often guilty of doing, because I ultimately believe that all of life can be explained by children’s books (which further reinforces my view on the value of storytellers, I guess) I will bring this back to a book that we, the Grant-Bowens, have been reading a lot. They All Saw A Cat is about a cat, as seen by a child, a dog, a flea, a bird, and a bat, among other animals, until, in the end, it sees itself. Each creature sees this cat differently, based on its size, perception, biology, and biases. The way the cat sees itself is the only way it could ever perceive itself in the world, unless that child, dog, flea, bird, bat, and anything else so inclined, shares the way *it* sees the cat. This not only changes the way the cat sees itself, but also the cat’s understanding of the way a child, dog, flea, bird, and bat sees things, too.

I used to think this should be required reading for all nonfiction writers, and then expanded it to all writers, period. Increasingly, I’m thinking it goes on the syllabus for life.

We all see the cat. But how do we see it? And more importantly, why do we see it as we do? If no one else pipes up to answer the question, we will only ever see it one way—our own way--and worse, never realize that there are other ways; ways we can’t even imagine.And they are all weird and surprising and beautiful, and they are all true.

The entitlement of the writer, or the solipsism a writer-free world. I know which I fear more. And so I hit ‘publish.’ Emily, send me your address and I’ll send you a book. It’s about a cat.

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My "cycle code speak"

I developed with Bestie to avoid eavesdropping from others.

We talk then change the subject then go back to,the subject then off topic and back.

Its specialised.

On a very long post readers will lose information.

So bestie and i would speak less about the most important topic but feel the most.

We were always in public or someone was "bugging" us.

So im delighted to see that y'all understand how it works. Snoop had to call y'all out and help y'all,understand how y'all been on auto save to save the Planet.

And have the information posted at the bottom for y'all to simple get it.

I knew exactly how he needed to tell y'all cause,Alex was telling me first thing when i woke up from sleep just now. I said "highlight the information above"

And he had Tree copy and paste the highlighted information in the order I wrote.

One reason people didn't catch onto how they were saving the world is that didn't matter. They were simply being human.

But i appreciate that Snoop went out of his time and went for y'all to make sure you understand why.

1 as a thank you and 2 to help us understand how humans actually are and make that very clear that humans aren't abnormal. We're normal!

So what the contact communications code is is just like you write 3 articles and then you merge them together keeping all the information in order. Then you hit each topic.

Now. Bestie and i when long time no see or in dangerous territory (lots of nosy aliens around to harm) we shuffled the articles so it would be out of order.

So it would be complex and a lot of silence at our public dinner table in a restaurant. While we ourselves minded the information to our hearts to reorder the information into an order. In silence and leaving gaps of space to know we did beginning and end.

Aliens in human form. Usually men would get pissed off and leave the restaurant and cause a scene. Then after then we would go back and do the cycle in order. Because we were safer.

So none of us are stupid. We just dont know what is going on

I can't help but conversation code it.

It isn't any different than the family going around the dinner table talking about their day.

I would do it with my Uncle Dad. Denise was too stupid to,follow along,instead getting bugged I would,talk after everyone talked. So Chris,would,talk,i would say 2-3 sentences about my day and then Nathaniel would say something and i would,say,how i was counter acting his actions. But not allow anyone,but humans to,understand.

Very serious issues needed slight clarification to my Uncle Dad after. He would double check,my safety. After dinner in,the living room

Meaning safe and,handled,I went to my room,first.,not,then,directly to,the living room.

So I don't know how to be uncoded.

Even,things I,write straight forward. End,in cliff hangers or some thing. A cliff hanger,is a code,for "more to,come"

I can't really change that. I'm just an extreme expert at communication.

With bestie and i it became a blood sport. Often she would arrive before me and find aliens she wanted kill. And i would watch her face of anger and wait and develop conversations that way. I would follow her lead.

Otherwise my goal was to keep aliens stupid and then watch them. They would be happy from our information. Information that hurt her and I. So they would stand and catch me looking and sit for safety. Thus notifying my protection detail of CIA agents and they would label my face under kill.

My eyes would narrow then when I looked back to bestie my eyes would open wider. A more comforting honest tell me honey what's going on face.

Then i would Alien stretch my soul ... Aliens thinking it was my skin. To notify "I'm still looking. They're going to die. 'This isn't my territory style'" which was mild to extreme torture and removing the kidnapped kids from extraterrestrial custody.

Bestie hated it. Because she put her life on hold instead of holding bee soulmate in her arms.

Those days i would fill the restaurant with the spirit of love. Usually my bestie would be having a super bad day. It depended where we sat. That was my auto cue.

When Tommy would see my soulmate stretch to order kills he became extremely sad. Because he would realize he could just killed Amanda.

But I would reassure him that wouldn't have worked. It would bad the world unstable due to alien attacks. We would just Moshe pit kill them all in the end after giving them a choice to live right an s rigid on their home planets.

So i would tell him "just see her" but shes married and so am I! "Be friends till the end. I have come to see her and you will, too. Invite him bestie over to you for a BBQ. Get drunk have fun just as we used to do over our house (or i would say at my house)" she would grab her phone and text he would say "maybe" and i would say "let's talk about your problems. Let him know you're struggling as much as him but in a different way" he would show up over her house as "enlisted to lighten to load" help her deal with her life stress.

Y'all don't know but shes been my only "irl" friend for over 10 years. My only friend. I've lived a normal sane life like many of you that have been kidnapped and loaded down under. And just regular people and most especially aliens that want to remain hidden.

People come and go But my life as friendship in real life has only revolved around her. I'm not ashamed to have only one friend. The rest of the time i spent with my soulmate. So I've been happy as can be as a POW.

This is how i know the world needs extreme help. My life sucks and i hate it. The same reasons my bestie hates hers. Because she can't be with her lover.

And family IRL.

Otherwise and because of that sad days For her became revenge kill days.

We could only kill extraterrestrials if they were criminals. The same as an evil human. It kept the balance and the world safe from alien invasions for revenge.

We thank Weck's restaurant in their unique location that used to be the Red Balloon in Los Lunas. Red Balloon was also a yummy restaurant to eat at.

But it was an alien establishment and i ordered humans to take it over. Thereby thus combining fate and history into a native New Yorker tounge that doesn't pronounce the letter R. from "Wrecked that alien bitch" to simply "Weck's"

Red Balloon was code word for "Alien Safe Here"

I made sure they understood they are not.

Most went down to Roswell from the Albuquerque metro area.

Those visiting "the moon" didn't know we had taken it over and visited freely. Those we killed because it was a criminal safety net - the Red Balloon. 99% of aliens going to eat had done something very wrong like kidnapping humans.

The CIA wait staff knew they could tell when Bestie was sad... So it was back to the wall where the bad alien was or back to the wall where I could see what was going on. The wait staff set us told us where to sit.

So i would switch with Bestie every so often to see what she saw. Because my neck pain prevented looking. Often it was "im fucking leaving she keeps looking at me!!"

Like a human looked at a human.

Which was delightful because it proved they knew they were wrong. "Oh my God that is so funny!!"

Usually I found the humor. Often Alex and Tommy would have "invisible dinner talk" and Alex would advise Tommy to basically romance surprise her. Just show up at the house and Alex would volunteer to oversee to help guide Tommy to allow John to be his friend. My bestie's husband.

In this way he could be Uncle in his daughter's life. Because that was what hurt the most.

So we took better care of them than we did ourselves as is obvious.

Our right. Our ruling.

This is why I rarely tell my own feelings. Because most of y'all would feel bad or sad or responsible for helping.

So now I can tell. Because now I've began the mass exercising of moshing our demons to sleep.

But I had to ensure each American was safe first and I had amnesia.

So I had to beat and destroy the strongest aliens on my own. Aliens stronger than me.

David and Goliath.

Except me "Go lie" I am goliath. Because that is my orders.

"Duh I've did" they told me. The weakling.

"Good" I'd say "let it continue. Disobey the 10 commandments. I can't stop you and that isn't my job any way"

My job is to kill. Force surrender. And destroy if they don't

I had to become an archangel. That was always a man's job. Always Alex's. No one but him has been an archangel until 2003 when Declan became one.

Then 2006 when Bestie did.

And now me and there are several others.

To honor bestie. Alex has given up the title of Archangel Michael.

Its a masculine form of her name and it would indicate they're lovers.

He has planned to enlist all his archangel titles under Archangel Gaberial. Gabriel is the masculine form. Spelling Gaberial without the -ia entitles it to be "for the woman". Me.

So no one shall name their sons Gabe. Gaberial or Gabriel or any spelling of such name. For men and hermaphrodite

However they shall be allowed to name their daughters and hermaphrodites "Gaberialla" in honor of me and in understanding he has already protected their right to live.

Any spelling. The above spelling notices "I am your Cinderella, Arch Angel Gaberial, I hereby dutify myself to your spirit to fight for the safety of all humans thereby all consequences shall be none."

When a child gets baptized that is what is said

Now consequences shall be none... Means eternal death to all alien invaders thus allowing earth to be free and clear from painful consequences caused by alien invasions.

Thus it is a choice a parent can not make.

"I am a Gaberialla" says a female voice. "I, too, am a Gaberialla" follows a deeper male voice.

This is allowed by Jesus.

$5 for who can answer "what does the term gaberialla replace in our new society?"

Here's your hint: 3 letter word

Thus at my Jesus Cult wedding. Many times "ahh boo!!" Startling and scary. Those of you that come to realize you've enjoyed fighting the alien nation will have the right to become an archangel Gaberial assistant. To follow many rules of the American Nation.

Because my soulmate has had issues in this lifetime to know who his friends are. Who has his back and who doesn't.

Many of our CIA we use Now will set to retire. Because i said to. Never will the skills or talent accumulated will to to waste. But its time to enjoy new jobs and new lives.

Not anytime soon. But eventually. For now the war must continue.

The spelling remains the same but it is pronounced "arc-Angel" a promise to provide the world with the rainbows the "arch-angels" have always dreamed of.

And also ark of thereby Noah whom is also me. Because we will all be Christianed upon an arch

I will with Tom, Alex and Andrew will bless the bestie to become the first female archangel in known existence in the 3 galaxies I've created with Alex.

Then she with Alex, Tommy, Frederick will then bless all the archangels into existence. Which will include me as we all bow to her feet Muslim style into prayer.

She is also the only known Full bloodied Scorpio on this planet. All the planets were perfectly aligned,,including the moon the night she was born. To be a 100% true and divine Scorpio.

So when you want to know more about her, google astrology sign SCORPIO.

And you will see how easy it was for us to devise the secret communication coded language that didn't beat Navajo code but was simply in time line as good as. She also as a reincarnate invented many codes throughout her 864,922,386,401 lives.

Like Candy she is one of my unknown daughters. Created from my spirit of war.

**Not Christina Hendricks aka Chandler - she is known from my womb in this lifetime. But another Candy. A Candy from the spirit of motherhood. A true 100% divine and perfection true Cancer. She is out of body. She too will be an archangel. Archangel Uril is Another name Alex will give up. Spelled Ariul. sounds like Aerial

To learn about her google the astrological sign Cancer. A video has been produced to know why her symbol is the crab. It was posted yesterday.

Her voice is in Charlie Brown indistinguishable due to the water. In the Muppet Babies the mom/nanny is also her. And in Loony Tunes the old gramma with the broom with Sylvester and Tweety.

Ariel is her learning about love. From me. Ursula. Its not based on a true story. It is the real story.

So I hope this has all made you pleased. Unworried for the future. And you resume your toilet paper gathering for current use and paper mache upon our return to land.

Toilet paper requires no glue unlike other paper. So it is perfect for paper mache dolls to create to burn while thinking of aliens.

Extraterrestrial are the biggest hoarders of them all.

So it will be all gathered and then given away since its already been bought from the factory repaid to the store for allowing purchases to be made easier from factories and then upscaled in pricing to pay for the religious experience of shopping.

Retail therapy is part of the True Jesus (me) religion.

Now please pray for my forgiveness and hope I can be with my true lover Soon.

Remember I got $5 on it that you read and understood what all I've just said.

0 notes

Text

“You will hear an unbelievable true story,” Primož Bezjak, one of the three actors from the Republic of Slovenia on a stage designed to look like a makeshift bunker, tells us at the beginning of the play entitled “Ich kann nicht anders,” which is having a brief run at La MaMa; its fourth and final performance is today at 5 p.m. “Some of you might find it boring, which will mean that you have chosen the wrong event for this evening. But the rest of you — and there will hopefully be quite a few — will find this intriguing, maybe even inspiring.” I was too uncertain about what was going on in the hour that followed to feel inspired, but I certainly wasn’t bored. As explained in the digital program, this fifth production of Beton Ltd., which is what the three performers call their ten-year-old Slovenia-based theater troupe, is intended to turn the audience into voyeurs witnessing the “selected intimate moments” of these three people’s everyday life. In the show itself, though, Bezjak tells us that it takes place in 1991, during the Ten Day War between Slovenia and Yugoslav Army shortly after Slovenia had established its independence. And so, the three sit around eating pizza or playfully gobbling and spitting out those Styrofoam packing peanuts or talking casually, when suddenly lights flash, they become alarmed, take out guns, and take cover behind a stack of boxes. At times, they are suddenly attending to bloody wounds. Just to make this weirder, amid much of the so-called casual conversation about politics or sex or getting older, are stylized monologues, in which the performers talk about one other in front of one other as if the others aren’t there. Mixed in with the casual everyday living and the tense crisis mode, is a deep dive into often obscure erudition. Let’s take that title. You may have wondered why it’s in German when the official languages of Slovenia are Slovene, followed by Hungarian and Italian, and the three performers at LaMaMa are speaking English. Ich kann nicht anders – which can be translated as “I can’t do otherwise” – is part of a famous quote attributed to the 16th century theologian Martin Luther, at a crucial moment when he spurred the Protestant Reformation. We can infer that they are referring to a moment when things are about to change. The mix of erudition and in-your-face theatricality can be jarring. In one fascinating exchange – which one senses may be at the heart of their enterprise — Katarina Stegnar says: “You know, Barnes* wondered… how could one turn disaster into art? Today this is done totally automatically. A nuclear power plant explodes and a year later the play opens in London. There is a tsunami on Sri Lanka and there will be a book and a film inspired by the book and a book inspired by the film and Naomi Watts attached to production. There is a war in Syria and it’s opening the Under the Radar festival. If you want to understand a disaster you have to imagine it, which is why we all need Ai Weiwei. In the end disaster leads to art. Maybe disasters are good for art.” Then Primož Bezjak replies: “Look: Art was never innocent; it is important for people to have something to talk about. Millions of people visit centres of contemporary art all the time even if they hate it. Just so they can talk about it, just so they know what is contemporary, so they can turn their noses up….” While they’re speaking, Branko Jordan is behind them wearing only his underpants, which are blotted with blood, then he strips off his underwear, and gives himself a sponge bath using water from a bucket. The other two strip off all their clothes, and join him in nude bathing. The nudity here is casual and incessant. I can’t tell you what “Ich kann nicht anders” adds up to, or even that it is a cohesive work of theater. There is such a frequent disconnect between what the performers saying and what they’re doing that it seemed to me to approach a parody of avant-garde theater. But I have to confess that much avant-garde theater has struck me as approaching self-parody. That the insights and pleasures of “Ich…” are scattershot – that the piece feels random — may be its main point. In the last discussion of the show, the three talk about how in their youth they had “real discussions. And it was ambitious: who we are, what we need to do…I don’t know where this meaning, has fucking disappeared to. And why. “

* The performer was referring to Julian Barnes, who wrote a piece for the New Yorker in 1989 entitled “Shipwreck,” which riffs on Théodore Géricault 1817 painting “Scene of Shipwreck” (also called the Raft of Medusa) which mediates on this question ‘ How do you turn catastrophe into art? Nowadays the process is automatic. A nuclear plant explodes? We’ll have to justify it and forgive it, this catastrophe, however minimally. Why did it happen, this mad act of Nature, this crazed human moment? Well, at least it produced art. Perhaps, in the end, that’s what catastrophe is for.” It’s worth noting that Barnes’ story, which was collected in his book A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters, was adapted to the stage.

Ich kann nicht anders review: Slovenian avant-garde theater troupe Beton at La MaMa “You will hear an unbelievable true story,” Primož Bezjak, one of the three actors from the Republic of Slovenia on a stage designed to look like a makeshift bunker, tells us at the beginning of the play entitled “Ich kann nicht anders,” which is having a brief run at La MaMa; its fourth and final performance is today at 5 p.m.

0 notes

Text

#MeToo revelations and loud, angry men: the feminism flashpoint of Sydney writers festival

New Post has been published on https://writingguideto.com/must-see/metoo-revelations-and-loud-angry-men-the-feminism-flashpoint-of-sydney-writers-festival/

#MeToo revelations and loud, angry men: the feminism flashpoint of Sydney writers festival

For anyone who thought the movement had lost momentum, the last few days have proved otherwise

Hours before the cornerstone Sydney writers festival panel about the #MeToo movement on Saturday night, the Pulitzer-prize winning author Junot Diaz with events still booked in Sydney and in Melbourne was on a plane out of Australia.

The day before, another festival guest, writer Zinzi Clemmons, had spoken from the audience during the Q&A of one of Diazs panels, questioning the timing of his recent New Yorker essay and asking the writer to reckon with his own alleged history of harm.

She then shared her story on Twitter, claiming he had cornered and forcibly kissed her when she was 26.

Clemmons was joined on Twitter by other women including another festival speaker Carmon Maria Machado who made their own accusations of his alleged misconduct. Diaz withdrew from his remaining appearances, and told the New York Times (without referring to the allegations specifically): I take responsibility for my past.

As the story unfolded on Twitter, the green rooms no journalists policy was enforced with more vigour. Understandable. For anyone who thought the #MeToo movement had lost momentum, the last few days proved otherwise.

Lets recap, moderator and former Crikey editor Sophie Black told the audience, before a panel that would be interjected by a protester, a whistle-blower, and one of Australias best known feminists. Weve got a lot to talk about.

On Friday, for instance, the Nobel prize for literature was cancelled amid a sexual assault scandal. The day before that, a Washington Post investigation told of 27 more women who had allegations of sexual harassment against talk show host Charlie Rose.

One of the journalists behind that investigation, Irin Carmon, was on the panel, along with Now Australias spearhead and spokesperson Tracey Spicer and the New York Times Jenna Wortham. Carmon had been working on the Rose story since 2010, but it was only when the #MeToo movement gathered steam that she was able to get it off the ground.

Tracey Spicer, Irin Carmon, Jenna Wortham and Sophie Black during a panel discussion. Photograph: Jamie Williams

[In 2010] the women werent ready to speak out, and I had to move on, she explained. But when people started to tell their own stories on their own terms, I thought, Maybe its time to go back to the story, maybe they are now feeling its safe enough.

The movement has made it easier, she said, but its still not easy.

Carmon talked about the burden of proof needed to publish a story alleging sexual crimes, and the emotional exhaustion it took for a victim to speak out. The Rose story, she said, had taken over her life. This is not just happening willy-nilly; people are not just doing it for fun. Having been up close in the machine and the aftermath, it is not fun. It is not glamorous just because a few people went to the Oscars.

Later, she said: I wish people knew that what reporters publish is just the tip of the iceberg of what we know, because it has to meet such a high standard. One of Harvey Weinsteins accusers, for instance, had a recording of her harassment and still wasnt believed … So many people dont have that kind of evidence.

Spicer agreed. Since her public call-out for #MeToo stories on Twitter in October, she said 1600 people had contacted her with allegations about 100 different Australian men.

Ive got beyond a dozen accusations against many of the alleged offenders [who we havent yet exposed], she said. And even with that, you have to almost act like youre part of the police force. Is there any clothing with DNA on it? Are there any diaries? Did you tell anyone at the time, a family member or a friend? Its incredibly difficult in this country.

So whenever you read these stories or see them on television, you know that they have been robustly researched.

Australias restrictive defamation laws work against the whistle-blowers, as do varied pressures inside newsrooms, which have been hampering investigations at home. Spicer has spent the past six months connecting the strongest of the stories with news outlets around the country but her efforts, she revealed, havent always been welcome.

This is a conversation thats not going to be very popular in this room, but its something Ive been wanting to say publicly for a long time. When we started doing these stories in this country … we had the support of Fairfax and the ABC, and they were tremendous, she said.

But recently, in the last two months, Ive seen mainstream what we would call old media organisations starting to pull away from some of these stories … Not only is it costly, not only is it difficult because of defamation, but its getting a little bit too close to our executives. And that is a true story.

For that reason, she has been taking stories to a broader array of outlets, including Guardian Australia, the Financial Review and News Corp. If you want to keep reading and hearing about these stories, contact the media outlets in Australia and tell them, she said.

At least one of the people who had told their story to Spicer was in the room; she found her way to a microphone during the audience Q&A. I came to Tracey with my story last year and she followed up with me. She said, Youre not the only victim of this man but we just cant get the story up …

You shouldnt have to be sitting on a stage, putting out a call, asking audience members to give you the resources to bring these man to justice, she continued. I have seen you done so much more than what your job description has asked you, and honestly, the responsibility lies with the media organisations.

Following the Diaz allegations, the panel also discussed so-called trial by Twitter: women making allegations against men on social media or blogs, sidestepping journalism and the justice system.

I dont agree with people naming people on social media, Spicer said, but I understand why people are [doing it]. They feel a frustration with the gatekeepers.

It was even more difficult for women who didnt fit the mould of the victims whose stories have so far been prioritised: white, privileged, straight and famous women. I dont think were dealing or talking about it at all the way we should be, in terms of non-white, hetero normative, straight [victims], said Wortham, who co-hosts the Still Processing podcast on race and pop culture.

Wortham also spoke about the toxicity of open secrets, referencing the shitty media men list which privately circulated New York late last year before it was exposed.

The shared document named men whose allegedly inappropriate and harmful behaviour had, in some cases, been known by many.

I had gone to drinks with those people, I had been alone with them, Wortham said. I was a young 25-year-old who didnt know any better, and Id been in situations that could have potentially been very difficult. And because they were open secrets, the onus was on me to know that that was a dangerous situation.

But she hadnt been tapped into the whisper network. Either I wasnt successful enough or I wasnt interacting with the people who were privileged enough to have that information and pass it along to me. I wasnt in the right place on the hierarchy of knowledge …

Weve developed these coping mechanisms to deal with these societal problems that are really insufficient, and put the [onus] on us.

The panels penultimate moment was a welcome surprise: notable Australian feminist and writer Eva Cox stood at a microphone with a question for the panellists.

Its not How do we stop that man from doing that to us?, but How do we stop men feeling like theyre entitled to?, she said.

We have to start looking at what we are doing to little boys to make them feel entitled. We need to sit down and start addressing the social problem, because we are still the second sex. And unfortunately, a lot of what were doing to fight this … is using a male-driven system to try to screw a male-driven system. It doesnt work.

As the applause died down in the audience, a lone voice could be heard from the front: a man who had been barred from the microphone during the Q&A was standing in front of the stage and screaming aggressively at the strong, accomplished women who sat in front of him.

HOW MANY INNOCENT MEN WILL GET TAKEN DOWN? he yelled, as he was escorted out. GEOFFREY RUSH IS AN AUSTRALIAN ICON!

The four panellists had spent the last 60 minutes illustrating why this movement wasnt going away. It took just one man, in one second, to succinctly prove their point.

An earlier version of this article implied journalists were removed from the green room following the Junot Diaz allegations. According to the festival, the green room was intended as a journalist-free space

Read more: http://www.theguardian.com/us

0 notes

Link

Alva Noë is a lifelong Mets fan who grew up in New York City in the 1970s. He is also a Professor of Philosophy at UC Berkeley who has published influential books on the nature of human action and experience. With his most recent volume, Infinite Baseball: Notes from a Philosopher at the Ballpark, Noë joins the distinguished line of American philosophers who have embraced the national pastime.

Many of the essays in this diverse collection draw on Noë’s columns from the NPR website, 13.7 Cosmos and Culture, now sadly defunct. A longer opening essay frames recurring themes: baseball as a juridical sport, the questionable urge to reduce it to a game of numbers, and the puzzles raised by performance-enhancing drugs. But the book ranges widely, from joint attention to the magic of the knuckleball, from instant replay to Beep Baseball for the vision impaired

The essays are short, sharp, and attractively written, colloquial but profound. You can read them in the breaks between innings of a baseball game and pretend that you are watching it with Noë. As he writes in a piece about baseball and language, “the thing baseball folks do more than anything else, even during a game, is talk about baseball.”

I talked to Noë before Opening Day.

KIERAN SETIYA: Your parents were not baseball fans. How did you fall in love with the Mets?

ALVA NOË: I grew up in Greenwich Village. My parents were “alternative,” you could say. They were artists and most of the people in our lives were artists — potters, painters, musicians, etc. This wasn’t a sports or fan culture, and professional baseball, professional sports in general, was something sort of beyond the horizon; it showed up mostly by way of transistor radio as a kind of window onto the straight world. My dad was also an immigrant, a Holocaust survivor who’d arrived from Eastern Europe at the war’s end. So I think at least part of baseball’s appeal for me, and for my brother, must have been that it was so very normal, so much a part of a larger culture that felt both strange but also comforting. Safety and comfort were a factor for me — as a child, I would listen to games at night under the covers. I associate that with security and pleasure. At the same time, I guess I’ve also felt that I needed somehow to serve a bit as an ambassador from baseball, or maybe from the wider culture, to my family. Why do I love baseball? What is it I love? How can I make sense of this to people for whom baseball is, well, unimportant? In a way, that’s what this book is about.

As for the Mets, well, it was over-determined that I became a Mets fan back in the early 70s. The Mets were actually the better New York team back then. They’d won the World Series in ‘69. I was too young to be aware of that — but I vividly remember watching Tom Seaver and Tug McGraw lead the Mets to the Pennant in 1973. They weren’t just better than the Yankees, they had the better story, or at least the story that made sense to me. The Mets were pretty good, but they were always the outsiders and the underdogs. They were the team for city kids, for Jews and Puerto Ricans. To me, they represented aspiration rather than entitlement and establishment, as with the Yankees. The Mets were summer barbecues in the park; the Yankees were upstate, White, and Republican. I’m not saying it’s true, but that’s how it felt. I could no more support the Yankees than I could support Richard Nixon. And although my parents were not baseball fans, they were enthusiastic opponents of Nixon. So there is a sense then in which the Mets were the closest I could get to an embrace of a kind of Americana.

Of course, it’s important that I didn’t consciously choose to be a Mets fan. That’s not really the kind of thing you choose. Just as you don’t choose to be born here or there. But there’s not choosing and not choosing. I think there is a way in which you do choose what team to love.

Here’s a comparison: Why does anyone have a New York accent? Why are there even accents? You might say that people simply grow up speaking the language of those around them. This is obviously true to a degree. You don’t grow up in New York speaking Cockney English. And yet, crucially, there is variety to the ways people talk and not everyone ends up talking just like those they grew up learning to talk with. I suspect that finally the only way to explain this is to recognize that there is a sense in which we do choose how we talk. Not quite explicitly, to be sure. But we find ourselves talking, roughly, the way we think ‘people like us’ are supposed to talk. New Yorkers as a group tend to talk the way they think they are supposed to talk. And I suspect this is true for other categories of identity.

In particular, I suspect it is true of being a fan. I didn’t choose to be a Mets fan, nor is it something I inherited like a nationality. But I think at some level I chose to be the kind of New Yorker who would be a Mets fan, and my parents did in some ways raise me to be that kind of person.

That comparison speaks to me! I lived in England until my early 20s and first encountered baseball – at a Mets game – during graduate school. But I love it now in a way I’ve never loved another sport. As it happens, I’ve also acquired what I like to describe as a “trans-Atlantic” accent. I sound dubiously American to British friends.

This leads me to a question about being a fan. At the beginning of your book, you cite a puzzle from one of Plato’s dialogues: are things good because we love them or do we love them because they are good? You argue that we don’t love baseball because it is special; it is special because we love it; and we love it because we grew up with it. It’s an endearingly unsentimental view, especially coming from the author of Infinite Baseball. But it made me wonder what you think of fans like me, who didn’t grow up with the sport. I don’t think baseball is objectively better than other games, but I do think it is objectively special. Am I wrong about that?

You are right. Baseball is objectively special, but not objectively better. For me this is like Tolstoy’s thought about unhappy families, that they’re all unhappy in their own way. Well, baseball is special, but so is American football, and so is soccer. But they’re all special in their own way. The point generalizes. For instance, there is something special about languages. French, German, Yiddish, but also Classical Chinese or Hausa. These are special languages. Not more special. And certainly not better. But special, yes. Objectively so.

There is a joke in Wittgenstein somewhere about a French General who marvels at the fact that in French, alone among all the languages, there is a perfect correspondence between the structure of the sentence and the structure of the underlying thought. The general is the butt of the joke. Wittgenstein’s point is that there is no external standpoint from which we can say that one language rather than another is better at expressing thought. But notice this leaves open that there is an internal standpoint from which it can feel mandatory to say just that. For someone inside a language, language fits meaning like a well-worn glove. If you are French, it seems as if the very way we join words together matches something essential in the way we think. And in a way that’s right, not wrong.

And so with baseball. It is special. But to understand why, you need to take up the standpoint from inside baseball.

I do think the whole question of an immigrant’s love of the game is a fascinating one. Sometimes being an outsider affords the opportunity for a special kind of appreciation. Think Hemingway and the bull fight. Or the British and their passion for American (especially African American) music. And then there’s the fact that it is one of the stories that baseball likes to tell about itself that it has served an important role in the American melting pot. People of different national origins as well as classes come together at the ball park. Children of immigrant fathers and their fathers become American at the ballpark. So your affection for the game taps into important themes.

This connects to another idea in Infinite Baseball. I say that to know baseball’s objective specialness, you need to take up the stance inside baseball. But baseball also reminds us, I think, that the inside stance is also always an outside stance. To play baseball is always at once to think about baseball. Maybe that’s even more pronounced in the experience of a convert such as yourself. You love the game, you take up the stance inside, but you remain, and probably always feel, like an outsider, at least to some extent. That’s true of me, too.

I like the idea that baseball is distinctively reflexive or that it thematizes reflexivity in a distinctive way. In your book, you call it a “forensic sport.” Could you say a bit about what that means?

A curious and unremarked fact about baseball is its preoccupation with questions of agency, credit, blame, liability, and the like. In baseball, it is typically not what happened that matters, but rather who is responsible for — who deserves the credit or blame for — what happened. Actually, it’s more subtle than that. What happened, in baseball, is in good measure determined by facts about liability and responsibility.

To see what I mean, consider the law. A person eats poison and dies. This description of the facts leaves open what actually happened. Was this a suicide, a murder, an accident or a misjudgment? To answer the question what happened? you need to decide, roughly, who’s responsible. That is, you need to ask what I call the forensic question. Did she eat the poison on purpose? Did someone slip it into her sherry? Did she squeeze the dropper too many times when preparing her sleeping draught? One can only know what happens when one makes decisions about what she or other persons did. And this is because what happened is actually made up out of facts about who’s responsible, about whodunnit.

Forensics, as we all know from police shows, is the science of whodunnit. More generally, it is the domain of the law and legal responsibility. And more generally still, “forensic” just means, roughly, having to do with agency, and so with responsibility, that is to say with warranted liability for praise and blame.

Baseball events, like legal ones, are, in this sense, forensic in nature. It isn’t the material facts — hitter swings bat, ball flies to right field and lands uncaught — that fix baseball reality. What we want to know is did the batter get a hit, do we credit him with driving a run home and advancing the runners? If so, then we can blame the pitcher for giving up the run. But if the batter reached on an error — if the fielder bungled the ball — then we don’t credit him with reaching base and driving in a run and we don’t blame the pitcher for letting it happen. In that case, something else happened. Yes, a run scored. But it was unearned.

In baseball, you need constantly to adjudicate questions of this forensic sort. That’s how you understand what’s going on. That’s how you tell the game’s story. Even something as basic as balls and strikes comes down, finally, to a judgment about who’s to be held praiseworthy or blameworthy. If you can’t hit what the pitcher is throwing, but you should be able to, then that’s a mark against you, it’s a strike. But if you couldn’t reasonably be expected to hit a pitch, well then, that’s not your fault, it’s the pitcher’s fault. That’s what a ball is. One of the big mistakes we make about baseball is that we think the strike zone is a physical space. Actually, it’s something more like a zone of responsibility.

Baseball reality, then, depends on our attention to these questions of agency and responsibility. To be a fan, or a player, that is, to care about and know what’s going on, you need to be an adjudicator, which is to say, a thinker. This is what makes baseball such an intellectual game.

There is something deeply right about this. If you compare the MLB rules with those of the NBA and the NFL, “judgment” comes up a whole lot more: 5 times in the NBA rules, 6 times in the NFL’s, 62 times in the official rules of Major League Baseball. It is a matter of judgment whether something is a wild pitch or a passed ball, a stolen base or defensive indifference. The definition of a strike makes this explicit: “A STRIKE is a legal pitch when so called by the umpire, which — (a) Is struck at by the batter and is missed; (b) Is not struck at, if any part of the ball passes through any part of the strike zone; (c) Is fouled by the batter when he has less than two strikes; … etc.”

As a philosopher, I love that peculiar self-reference: “when so called.” At the same time, advocates of baseball analytics are prone to complain about some of the phenomena that implicate human judgment: about the arbitrariness of fielding errors and umpires’ shifting strike zones. What do you make of those complaints?

Great question! I love the job played by judgment in baseball. Its what makes the game so vital. Baseball highlights the fact that you can’t eliminate judgment from sport, or, I think, from life. Sure, you can count up home runs and strikeouts and work out the rates and percentages. You can use analysis to model and compare players’ performances. But you can’t ever eliminate the fact that what you are quantifying, what you are counting, that whose frequency you are measuring, is always the stuff of judgment — outs, hits, strikes, these are always judgment calls.

We as a culture are infatuated with the idea that you can eliminate judgment and let the facts themselves be our guide, whether in sports or in social policy. Baseball reminds us that there are limits. You can’t take the judge out of baseball any more than you can take him or her out of the court room. And that’s not because there aren’t facts of the matter, or because there aren’t precise rules. It’s because no rule is so precise that there are no hard cases. And hard cases demand good judges.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m all for trying to get it right. If slow-motion replay lets you see what really happened during a close play at home plate, then I’m in favor of it. But the use of instant replay doesn’t eliminate judgment, it only highlights the role it plays. It is umpires at a remote location who make their call on the basis of the videotape. The tape doesn’t read itself and issue a decision.

And if it did — if down the road we replaced the umpire by some kind of AI — that would either spell the end of baseball, or, more likely, it would shift the locus of dispute, adjudication, and judgment. To my mind umpires aren’t measuring devices. They are participants in the game. The idea that you might replace them with machines makes about as much sense as the idea that you might, in the interest of improving the game, get rid of the players themselves.

Maybe underlying all this is the worry that judgment, of its very nature, is subjective and so arbitrary. But a good judge — which means not only someone with good eyes and knowledge of the rules, but an experienced and fair judge who understands what’s going on and who knows where to position him or herself to make the call — is anything but subjective or arbitrary.