#maria susanna cummins

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

For no other reason but my own curiosity, I made a list of all the literary references in Clockwork Angel (I also want to do this for Clockwork Prince and Clockwork Princess once I get around to rereading them).

*note: iirc, A Tale of Two Cities is referenced in all 3 TID books, so I'm only gonna list it once.

Some patterns I noticed are that Tessa seems to be a fan of Dickens and Collins.

Sir Galahad (knight of King Arthur)

Inferno (Dante)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll)

Oliver Twist (Charles Dickens)

A Tale of Two Cities (Charles Dickens)

Lady Audley’s Secret (Mary Elizabeth Braddon)

Boadicea (Alfred Tennyson)

The Trail of the Serpent (Mary Elizabeth Braddon)

The Moonstone (Wilkie Collins)

Armadale (Wilkie Collins)

The Woman in White (Wilkie Collins)

The Lamplighter (Maria Susanna Cummins)

The Three Musketeers (Alexandre Dumas)

Prothalamion (Edmund Spenser)

Jane Eyre (Charlotte Bronte)

Ivanhoe (Walter Scott)

Odes (Horace)

Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austin)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

almost calculated to rivet the reader

I was recommended the book The Bestseller Code: Anatomy of the Blockbuster Novel by another editor at the publishing house I work for, who was impressed at the thought of an algorithm that could predict whether a book would be a bestseller with 72 percent accuracy.

As someone who reads “literary” novels, has a disdain for tech evangelists bordering on the visceral, and regards the development of data-driven publishing with mistrust, I expected to be annoyed by the book. But it’s ultimately not quite as offensive to those sensibilities as it might seem. Rather than a “code” to help people write novels that’ll sell, or an algorithm of some kind that might drive book acquisitions in years to come, The Bestseller Code is about exploring why bestsellers like The Da Vinci Code or Fifty Shades of Gray appeal the way they do. And it offers support, through text mining (the process by which one discovers and extracts particular textual features from a book) and machine learning (the way one might process those features by feeding them into a machine that goes on to make predictions about, say, whether a given manuscript will achieve bestseller status or not), for research that was already done by folks like the scholar Christopher Booker, who read hundreds of books over decades, the old-fashioned way, and identified seven main plots for fictional narratives that authors Jodie Archer and Matthew Jockers find are corroborated by their own data.

Granted, there’s a bit of Jennifer Weiner-type “the commercial lit popular authors write keeps getting badmouthed by critics and the Literary Establishment!” stuff in the book. There’s also one baffling moment where Archer and Jockers make a claim that “the range of existential experience was much greater in bestsellers,” and defend that claim by talking about particular verbs that appear more often in bestselling novels than in non-bestsellers: “bestselling characters ‘need’ and ‘want’ twice as often as non-bestsellers, and bestselling characters ‘miss’ and ‘love’ about 1.5 times more often than non-bestsellers.” Verbs and isolated actions do not existential experiences make! But at root, Archer and Jockers’s research is the product of curiosity about what makes mainstream bestsellers sell the way they do, and whether readers have figured something out that acquisitions editors at big houses may not have yet.

As it turns out, there’s a degree of technical sophistication in Fifty Shades of Grey or The Da Vinci Code in the way these books follow a plot arc that manages to perfectly satisfy a commercial-fiction reader’s desire to be thrilled by dramatic stories and the fantasies they play upon. Specifically, for these books, it’s the “rebirth” plot, in which a character experiences change, renewal, and transformation. Which doesn’t sound revolutionary. But if you look closely at the plot structure, and the sequence of emotional beats in both novels, you see a rollercoaster shape that’s almost calculated to rivet the reader: these peaks of high, low, a high-high, a mild low, another smaller high, a low, and a final high (unless, like Fifty Shades, you need another low to set the reader up for the sequel). Authors and readers alike seem to have stumbled on such perfect, sophisticated structures. The writers happen upon them, rather than consciously being educated in them or consciously crafting them as more literary writers often do; readers seem to hunt them out by instinct: the books that best follow one of the seven plot structures are the ones that rise to the top.

There’s also one moment in The Bestseller Code that’s genuinely affecting, in the context of a discussion of Maria Susanna Cummins’s novel The Lamplighter, which in its time was scorned by Nathaniel Hawthorne and James Joyce. As Archer and Jockers put it, bestsellers and commercial novels are set in emotional terrains, more so than public ones. That is, they’re about their characters as they feel and act, within a world that’s taken as a given, rather than what novels classified as “literary” are often about—characters having to navigate a sociopolitical world that is itself a subject for the author’s comment, or an author’s self-aware exercise of and experimentation with language. And these novels “work for huge numbers of readers not because of what they say to us but what they do to us.” As such, these novels “need no shaming”: they just exist on a separate plane from the literary ones.

In the end, I didn’t mind getting this dispatch from that plane. I make occasional trips to other such planes: sometimes I’m in the mood for, say, Joe Abercrombie’s brand of fantasy, and I’ve read all the Harry Dresden novels; I also love some books that are the literary equivalents of summer blockbusters, like the Expanse series. But I know I won’t descend to the bestseller plane very often—and I do consider it a descent. To my mind, craft and thrill alone don’t give novels the most merit. I don’t read just to be entertained or to be moved, which is what bestsellers offer. I read in order to be made to think, in precisely the ways those literary, public-terrain, sociopolitical novels make me think. And I value them because they linger. They don’t just do things to me, work on me, crash over me like a wave and then recede; they speak to me, just as Archer and Jockers say, and what they say to me lives inside me for years to come.

What’s more, I already suffer enough with the tendency to “identify” with the characters in books I read without venturing into ones that indulge or depend upon that instinct as bestsellers do.

Finally, while Archer and Jockers’s algorithm does a fine job anatomizing bestsellers in a way that speaks to the merit they do have and the function they do serve, I don’t know that I’d trust its recommendations even if I were a passionate reader of bestsellers, considering the book the algorithm picked as the absolute best representation of what it considers a bestseller is Dave Eggers’s The Circle.

Which does reinforce that what an algorithm can’t understand is context. What keeps The Circle from being a bestseller, to my mind, is that the conceit—a woman who goes to work for a tech firm and is schooled in the particular inhumanities she needs to adopt in order to succeed in that increasingly human environment—is not the most engaging. The story may be too close to a specific reality, as opposed to the everyday worlds (e.g., in John Grisham, Jodie Picoult, or Danielle Steel) or the heightened settings (e.g., in The Da Vinci Code or Fifty Shades) in which bestsellers are best set. Perhaps the world in which The Circle takes place is so specific, and its concerns so urgent, that it doesn’t even need to be fictionalized to be of most interest; it seems that representation of Big Tech in memoir, like Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley, does better in the marketplace. And finally, Eggers himself is more a literary than a commercial author, something buyers of commercial fiction might be mindful of and trust less than one of the established names in the bestseller market. And he represents a different, past era in even literary fiction. We’re not in the age of the “Brooklyn Books of Wonder” anymore—the humorous triumph over adversity, the twee search for meaning and for love that characterized books of a certain time in the early 2000s. Really, all Eggers’s attempts to succeed beyond that trend—Zeitoun, What Is the What, The Monk of Mokha, A Hologram for the King—seem to me to have been tepidly received. The culture has moved on from his particular moment, and it moves in vogues an algorithm can’t always track.

I’ll also say that, seeing how Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, another book I reread recently, did so well in its day, and how it holds the fuck up—the plot and writing remain absorbing, and the atmosphere as seductive and pleasurable as ever; and that it gets namechecked so often in trends like dark academia suggest teens are exercising their beautiful prerogative to learn all the wrong lessons from that book to this day—I’ll say it’s a safe bet you can write a literary bestseller too, if you wanted to.

*

Anyway. Perhaps you’re reading this piece hoping to learn how to write a bestseller yourself. If so, here’s the skinny:

Keep your primary focus on two or three themes. And keep those themes basic. Archer and Jockers list ones like “kids and school”; “family time”; “money”; “crime scenes”; “domestic life”; “love”; “courtrooms and legal matters”; “maternal roles”; “modern technology”; “government and intelligence.”

Make sure your book has a central conflict—and make sure your protagonist is an active agent in that conflict and in her life generally, knowing what she needs and going for it, acting and speaking with a degree of assurance. Characters in bestselling novels grab, think, ask, tell, like see, hear, smile, reach, and do. Characters in lower-selling literary novels, on the other hand, murmur, protest, hesitate, wait, halt, drop, demand, interrupt, shout, fling, whirl, thrust, and seem.

Shape your story to fit one of the seven archetypal plotlines the authors identify:

A gradual move from difficult times to happy times

The reverse, a move from happy times to more difficult ones

A coming-of-age story or rags-to-riches plot

A “rebirth” plot in which a character experiences change, renewal, and transformation

A “voyage and return” plot in which a character is plunged into a whole new world, experiences a dark turn, and finally returns to some sort of normalcy

Another “voyage and return” plot in which the character herself voyages into the new world, fights monsters, suffers, and finally completes some sort of quest

A story in which your protagonist overcomes a villain or some threat to the culture that must be eliminated so she can change her fortunes back to the good

And make sure you time the emotional beats of your story to follow the curve of your plotline. For instance, The Da Vinci Code and Fifty Shades both follow the “rebirth” plot, and the respective authors ensure the arcs of the romances in both books match the curve of the plotline too, keeping the reader hooked in a way that’s, ultimately, structural.

Be sure to pepper your plot with scenes in which characters are intimate in casual ways. Much is made in The Bestseller Code of the intimacy reflected in a tactic John Grisham uses in a couple of his novels, which is to have his protagonist go over to a love interest’s house with wine and Chinese to just hang out and let her in on how he’s feeling.

Sex that doesn’t drive the plot forward doesn’t go over well. Avoid it. Even in romance novels (as opposed perhaps to erotica), sex is usually in service of the storyline.

Seek for a balance between features in your prose that speak to the more literary, refined style that often comes from institutions of education and letters, and the more journalistic, conversational, everyday style of writing one might intuitively associate with commercial fiction (shorter sentences, snappier prose, with more conversational and casual writing, more words like “okay” or “ugh”). These aren’t especially rigorous categories, I’m aware. Just use your best guess; you’ll probably be fine.

#books#literary#jodie archer#matthew jockers#dave eggers#anna wiener#brooklyn books of wonder#commercial fiction#e. l. james#maria susanna cummins#jennifer weiner#donna tartt

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

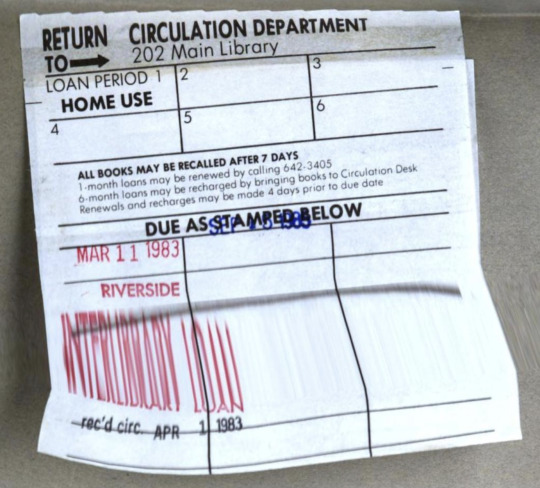

Distorted interlibrary loan slip.

From the back matter of Haunted Hearts by Maria Susanna Cummins (1864).

#Google Books#digitization#art#lit#tech#books#rare books#book arts#library#libraries#used books#old books#photography#new media#distortion#circulation slip#stamps

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nathaniel Hawthorne, in between hours spent jerking it to his own paragraphs of mind-numbing building description, threw tantrums about Maria Susanna Cummins selling more books than he did

pass it on

#literature opinions#like I'm not saying The Lamplighter is GOOD#but he sure did get furious over female writers outselling him#maybe if you spent a bit more time on plot and less time undressing New England infrastructure with your prose dude#classic literature#I have a friend who sends me pictures of herself discreetly flipping off the statue of him every time she goes to Salem#such is my loathing of Mr. Hawthorne's work

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buncombe Co. NC Genealogies and Histories #northcarolinapioneers

Buncombe County Wills and Estates

Buncombe county was formed in 1791 from parts of Burke County and Rutherford Counties. It was named for Edward Buncombe, a colonel in the American Revolutionary War, who was captured at the Battle of Germantown. The large county originally extended to the Tennessee line. Many of the settlers were Baptists, and in 1807 the pastors of six churches including the revivalist Sion Blythe formed the French Broad Association of Baptist churches in the area. In 1808 the western part of Buncombe County became Haywood County. In 1833 parts of Burke County and Buncombe County were combined to form Yancey County, and in 1838 the southern part of what was left of Buncombe County became Henderson County. In 1851 parts of Buncombe County and Yancey County were combined to form Madison County. Finally, in 1925 the Broad River township of McDowell County was transferred to Buncombe County. Genealogy Records available to members of North Carolina Pioneers Images of Will Book B, 1869 to 1899 Names of Testators:

| Alexander, George C. | Allen, Autonia | Baird, Eliza T. | Baird, Mary A. | Banks, H. H. | Banks, S. M. | Bell, Thomas | Brand, Hann | Brank, Joseph R. | Brittain, George W. | Brittain, William | Brookshire, Lula | Brown, Nathan | Brown, Nathaniel | Brown, William H. | Buchanan, W. A. | Burnett, Elrige | Burnett, James M. | Burnham, Hiram | Buttam, William | Calloway, Sarah Ann | Carter, Daniel W. | Chambers, William | Chambers, William Sr. | Chunn, Joseph | Clark, Jesse | Cochran, Harriet | Cole, Joel | Coleman, William | Conley, John | Crane, Mary Ann | Cunningham, E. H. | Cunningham, John W. | Curtis, B. J. | Daugherty, Lemuel | Davis, Asbery | DeBrull, Susanna | Duffield, Charles | Dula, Thomas | Edney, James M. | Edwards, Helen Maria | Eller, Adam | Eller, William | Embles, Joseph | Endley, James | Erwin, William A. | Frank, John | Freer, Carolina | Frisbee, William | Garren, Marion | Green, Jeremiah | Green, Katherine | Hall, A. E. | Hampton, Levi | Hawley, Levi | Henderson, David | Henderson, L. D. | Henry, James L. | Herndon, E. W. | Herrick, Edwin Hayden | Hyatt, P. A. | Hyman, Ellen | Ingram, Louis | James, Silas | Johnson, A. R. | Johnson, Henry J. | Johnson, Rufus | Johnson, V. D. | Johnston, Hugh J. | Jump, William | Kennedy, John P. | Kimberley, Bettie | Lanning, John | Lanning, Rebecca | Lee, Stephen | Lenoir, Betsy | Litcomb, Margarett | Love, Lorenzo | Luther, Laura | Luther, Solomon | Lynch, Martha J. | McBrayer, William | McGill, Wardlaw | Mercer, Sarah Ann | Merrell, John | Merriman, Branch H. | Middleton, Henry | Miles, Levin | Miller, Henry | Miller, Peter | Moody, Mary Janet | Mordecai, G. W. | Morgan, David | Morgan, Noah | Morrow, Ebenezer | Murdock, Margaret | Murphy, Laura | Murray, Patience Marcella | Murray, Robert A. | Murray, William S. | Palmer, C. B. | Patton, Eliza W. | Patton, John E. | Penland, M. P. | Pinner, Hugh | Plummer, William G. | Polk, Thomas | Poor, John | Pullium, R. W. | Randolph, Mary | Rankin, W. D. | Ratcliff, M. J. | Reed, Jacob | Reed, William R. | Revis, W. C. | Reynolds, John | Reynolds, John D. | Richards, Charles B. | Roberson, James Alford | Roberts, James Riley | Roberts, Joshua | Roberts, M. | Roberts, Thomas O. | Rogers, Caroline M. | Roselee, Sarah | Rumple, Robert | Russell, W. H. | Saunders, Benjamin F. | Shackleford, P. C. | Sluder, J. E. | Sluder, John | Southee, Joseph | Smith, B. J. | Smith, F. A., Mrs. | Smith, James T. | Smith, J. H. | Smith, Owen | Smith, William A. | Stepp, Rachael | Stevens, Francis M. | Stevenson, Abraham | Stewart, John Curtice | Stroup, Nancy | Swain, Eleanor H. | Taylor, Robert J. | Wallack, Isadore | Weaver, Jesse R. | Weaver, John S. | Weaver, M. M. | Wells, J. R. | Whitaker, Henry | White, David | Woodcocke, J. A. | Woodfin, Eliza | Worth, Frederick | Young, Lewis

Images of Buncombe County Will Book C, 1887 to 1897 Names of Testators:

| Adams, Daniel D. | Adams, Julia W. | Alexander, George Newton | Arnold, Henry | Ashworth, Johnson | Austin, J. H. | Baird, Rebecca | Ballard, Caroline | Barker, Clarence Johnson | Blount, John Gray | Braunch, William George | Broesback, Anna | Brown, Daniel | Brown, Mary T. | Budd, Margaret Anderson | Call, John D. | Cameron, Paul | Carpenter, John | Carpenter, John (1911) | Carroll, John L. | Carter, Melvin Edmondson | Cathcart, William | Cathcart, William (1805) | Cathey, J. L. | Cawble, Jacob | Chambers, John C. | Chapman, S. F. | Chapman, Verina | Christiansen, George | Cole, Ann B. | Clark, Adger | Clemmons, E. T. | Cortland, Mary Katharine | Croft, Sarah Ann | Cummins, Anson W. | Cushman, Walter S. | D' Allinges, Baron Eugene | Davidson, Thomas F. | Dobbins, Mary | Ducket, Margaret | Frady, J. A. | Frady, John | Fulton, Mary | Garren, David | Gask, B. S. | Goodrum, Maria | Haggard, Elliott | Hendry, Theodore | Henry, Robert | Hill, Wylie | Hines, W. F. | Israel, Levina | Johnson, Julius | Johnston, Andrew H. | Johnston, William | Jones, R. L. F. | Lagle, W. S. | Lindsey, Andrew J. | Mason, Lavinia | McHemphill, William | McMerrill, John | McNeal, Florella | McRee, C. E. | Melke, Arthur | Meyers, Sarah Ellick | Meyers, Sarah Thayer | Miller, George | Miller, Joseph M. | Moore, Harry V. | Murdock, David | Murray, J. L. | Neilson, M. A. | Peller, Joseph | Penland, William M. | Pinketon, James | Pinner, Leander | Powell, Martha J. | Price, Linus | Randall, James M. | Randall, Matthew | Reed, John Sr. | Reeves, John | Reynolds, Alice | Roberts, J. R. | Schultz, Andrew | Spivey, B. F. | Starnes, Jacob | Summer, Richard | Swain, Eleanor H. | Tagg, Marcellus J. | Tennent, Charles | Tennent, Marianne | Tompkins, Frederick W. | Washington, Julia | Weaver, M. M. | Webb, S. W. | Weber, August | West, George W. | Whitaker, L. W. | White, Edward S. | Wilson, Alfred

Images of Will Book A, 1831 to 1868 Names of Testators:

| Alexander, James | Alexander, James C. | Alexander, Lorenzo D. | Anderson, William | Arrington, James | Ashby, John | Ayres, C. | Baird, B. | Baird, Hannah | Ball, Joel | Bell, Thomas | Boyd, James | Brevard, John | Burlison, Edward | Call, John | Candler, Zachariah | Carter, Jesse | Carver, Joseph | Chambers, John | Cochran, Harriett | Cochran, William | Cole, Jesse | Cole, Joseph | Collins, Riddick | Cooke, Joseph | Curtis, Benjamin | Curtis, Delilah | Dale, Richard | Davidson, Samuel | Davidson, Sophronia | Davis, John | Davis, Margarett | Davis, William | Dillingham, Absalom | Dilliingham, Rebecca | Dougherty, John | Doweese, Garrett | Edmons, Elizabeth | Edwards, David | Edwards, Isham | Eller, Mary | Flagg, William | Fortner, John | Foster, Mary | Foster, Thomas | Foster, Thomas | Garmon, William | Gaston, Thomas | Gentry, John | Gilbert, Daniel | Gill, Rebecca | Gillispie, Francis | Goodlake, Thomas | Gousley, Hugh | Grantham, Joseph | Green, Jeremiah | Gudger, William | Harper, Lot | Harris, Able | Hawkins, Rachel | Henry, Dorcas | Holcombe, Obediah | Hutsell, Elizabeth | Ingle, Elizabeth | Ingram, Thomas | James, Thomas | Jarrett. Fanny | Johnston, A. H. | Jones, Ebed | Jones, George W. | Jones, Thomas | Jones, Wiley | Jones, William | Killian, William | King, Jonathan | Lackey, John | Lane, Sarah Ann | Livingston, John | Low, Stephen | Lowrey, James | Lusk, John | Marson, William | Martin, Jacob | McBrayer, James | McDonnell, William | McDowel, Athan | McFee, John | Means, John | Merrell, Benjamin | Merrell, Jesse | Merrell, John | Morgan, James | Morrison, John | Murdock, William | Nelson, William | Owens, John | Palmer, Jesse | Palmer, J. T. | Patton, Ann | Patton, James A. | Patton, James | Patton, James W. | Patton, John | Peavy, Bartlett | Peek, Jesse | Penland, John | Pinner, Burrell | Pitman, Thomas | Plemans, Peter | Poor, Isaac | Porter, Edmund | Porter, William | Potter, James | Powers, Brady | Prestwood, Johnathan | Reaves, Malachi | Reed, Eldred | Reed, Jane | Reed, Peter | Reynolds, Joseph | Roberts, John | Robeson, Andrew | Robeson, Jonah | Robeson, William | Robird, Robert | Rogers, Andrew | Saddler, John Roberd | Saunders, Benjamin | Sharp, Thomas | Smith, James M. | Smith, James M. (1864) | Spier, Alexander | Stepp, Silas | Stockton, Richard | Summers, Richard | Thrash, Valentine | Turner, James | Vance, Priscilla | Warren, Robert | Weaver, J. T. | Wells, Leander | Wells, Thomas | West, Henry | West, John | Whitaker, John | Whitaker, William | White, Ann | Whitesides, John B. | Whitmire, Christopher | Williamson, Elijah | Williamson, Elizabeth | Williamson, Richard | Willis, John | Wilson, John | Woodfin, J. W. | Wyatt, Shadrack | Young, John | Young, Rosannah | Young, Sarah

Indexes to Probate Records

Wills 1831 to 1868; Wills 1868 to 1899; Wills 1887 to 1897

Find your Ancestors Records on North Carolina Pioneers SUBSCRIBE HERE

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2gOnCGA

1 note

·

View note