#marabout Casablanca

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tomb of Marabout Sidi Belyout in Casablanca, Morocco

French vintage postcard

#marabout#sepia#belyout#casablanca#photography#vintage#postkaart#ansichtskarte#morocco#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#marabout sidi belyout#postal#briefkaart#photo#tomb#sidi#tarjeta#historic#french#postkarte

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sidi Abderrahmane

2018

0 notes

Text

Témoignage de retour d'affection chez le grand marabout guezo vignon

Témoignage de retour d’affection chez le grand marabout guezo vignon

Merci maitre Après ma rupture avec mon chéri j’étais tombé dans la dépression, je n’arrivais pas à surmonter et a accepter que je l’avais perdu. Je savais que sa nouvelle copine l’avait envoûté, j’ai alors fais une vision chez le grand marabout guezo vignon qui me l’a confirmé. Grâce à son rituel de retour affectif, mon homme est revenu, et on vit actuellement ensemble. Merci maître. Pour plus…

View On WordPress

#adresse marabout Paris#comment travail un marabout#est ce que le Maraboutage existe#grand marabout#grand marabout au Benin#grande marabout#guérisseur traditionnelle#les meilleurs marabout du Mali#maison marabout coffret#marabout#marabout africain#marabout africain Marseille#marabout africain paris#marabout africain sérieux#marabout Avignon#marabout île de France#marabout bordeaux#marabout c&039;est quoi#marabout Canada#marabout Casablanca#marabout Casamance#marabout dangereux#marabout en arabe#marabout France#marabout honnête et sincère#marabout Lille#marabout lyon#marabout Mali Bamako#marabout manuscrit#marabout marocain Marseille

0 notes

Photo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

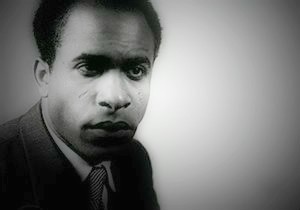

Franz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (French pronunciation: [fʁɑ̃ts fanɔ̃]; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a Martiniquais-French psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and writer whose works are influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism. As an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical, Pan-Africanist, and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology of colonization, and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization.

In the course of his work as a physician and psychiatrist, Fanon supported the Algerian War of Independence from France, and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front. For more than five decades, the life and works of Frantz Fanon have inspired national liberation movements and other radical political organizations in Palestine, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the United States. In What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction To His Life And Thought, leading Africana scholar and contemporary philosopher Lewis R. Gordon remarked that "Fanon's contributions to the history of ideas are manifold. He is influential not only because of the originality of his thought but also because of the astuteness of his criticisms...He developed a profound social existential analysis of antiblack racism, which led him to identify conditions of skewed rationality and reason in contemporary discourses on the human being."

Biography

Early life

Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French département. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, was a descendant of enslaved Africans and indentured Indians and worked as a customs agent. His mother, Eléanore Médélice, was of black Martinician and white Alsatian descent and worked as a shopkeeper. Fanon was the youngest of four sons in a family of eight children, two of whom died in childhood. Fanon's family was socio-economically middle-class. They could afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, then the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon had the writer Aimé Césaire as one of his teachers.

Martinique and World War II

After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval troops were blockaded on Martinique. Forced to remain on the island, French sailors took over the government from the Martiniquan people and established a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and isolation under the blockade, they instituted an oppressive regime; Fanon described them as taking off their masks and behaving like "authentic racists." Residents made many complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct by the sailors. The abuse of the Martiniquan people by the French Navy influenced Fanon, reinforcing his feelings of alienation and his disgust with colonial racism. At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a "dissident" (the coined word for French West Indians joining Gaullist forces), traveling to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces.

He enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre. When the Nazis were defeated and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photo journalists, Fanon's regiment was "bleached" of all non-white soldiers. Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon (Provence). Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.

During the war, Fanon was exposed to severe European anti-black racism. For example, white women liberated by black soldiers, often preferred to dance with fascist Italian prisoners, rather than fraternize with their liberators.

In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique. He lasted a short time there. He worked for the parliamentary campaign of his friend and mentor Aimé Césaire, who would be a major influence in his life. Césaire ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon stayed long enough to complete his baccalaureate and then went to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry.

Fanon was educated in Lyon, where he also studied literature, drama and philosophy, sometimes attending Merleau-Ponty's lectures. During this period, he wrote three plays, which are lost. After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon did a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole under the radical Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles. He invigorated Fanon's thinking by emphasizing the role of culture in psychopathology.

After his residency, Fanon practised psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, for another year and then (from 1953) in Algeria. He was chef de service at the Blida–Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. He worked there until being deported in January 1957.

France

In France while completing his residency, Fanon wrote and published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon Black people. Originally, the manuscript was the doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled "Essay on the Disalienation of the Black"; the rejection of the dissertation prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. For his doctor of philosophy degree, he submitted another dissertation of narrower scope and different subject. Left-wing philosopher Francis Jeanson, leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network, read Fanon's manuscript and insisted upon the new title; he also wrote the epilogue. Jeanson was a senior book editor at Éditions du Seuil, in Paris.

When Fanon submitted the manuscript of Black Skin, White Masks (1952) to Seuil, Jeanson invited him for an editor–author meeting; he said it did not go well as Fanon was nervous and over-sensitive. Despite Jeanson praising the manuscript, Fanon abruptly interrupted him, and asked: "Not bad for a nigger, is it?" Jeanson was insulted, became angry, and dismissed Fanon from his editorial office. Later, Jeanson said he learned that his response to Fanon’s discourtesy earned him the writer's lifelong respect. Afterward, their working and personal relationship became much easier. Fanon agreed to Jeanson’s suggested title, Black Skin, White Masks.

Algeria

Fanon left France for Algeria, where he had been stationed for some time during the war. He secured an appointment as a psychiatrist at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. He radicalized his methods of treatment, particularly beginning socio-therapy to connect with his patients' cultural backgrounds. He also trained nurses and interns. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale, after having made contact with Dr Pierre Chaulet at Blida in 1955.

In The Wretched of the Earth (1961, Les damnés de la terre), published shortly before Fanon's death, the writer defends the right of a colonized people to use violence to gain independence. In addition, he delineated the processes and forces leading to national independence or neocolonialism during the decolonization movement that engulfed much of the world after World War II. In defence of the use of violence by colonized peoples, Fanon argued that human beings who are not considered as such (by the colonizer) shall not be bound by principles that apply to humanity in their attitude towards the colonizer. His book was censored by the French government.

Fanon made extensive trips across Algeria, mainly in the Kabyle region, to study the cultural and psychological life of Algerians. His lost study of "The marabout of Si Slimane" is an example. These trips were also a means for clandestine activities, notably in his visits to the ski resort of Chrea which hid an FLN base. By summer 1956 he wrote his "Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister" and made a clean break with his French assimilationist upbringing and education. He was expelled from Algeria in January 1957, and the "nest of fellaghas [rebels]" at Blida hospital was dismantled.

Fanon left for France and travelled secretly to Tunis. He was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA). He attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution. In this book Fanon reveals war tactical strategies; in one chapter he discusses how to open a southern front to the war and how to run the supply lines.

Death

Upon his return to Tunis, after his exhausting trip across the Sahara to open a Third Front, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced some remission of his illness. When he came back to Tunis once again, he dictated his testament The Wretched of the Earth. When he was not confined to his bed, he delivered lectures to Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) officers at Ghardimao on the Algero-Tunisian border. He made a final visit to Sartre in Rome. In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip to the U.S. for further leukemia treatment.

Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961, under the name of "Ibrahim Fanon", a Libyan nom de guerre that he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front. He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs' (chouhada) graveyard at Ain Kerma in eastern Algeria. Frantz Fanon was survived by his French wife Josie (née Dublé), their son Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendès France. Josie committed suicide in Algiers in 1989. Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in international law and conflict resolution. She has also worked for UNESCO and the French National Assembly, and serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier married Valérie Fanon-Raspail, who manages the Fanon website.

Work

Black Skin, White Masks is one of Fanon's important works. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon psychoanalyzes the oppressed Black person who is perceived to have to be a lesser creature in the White world that s/he lives in, and studies how navigates the world through a performance of White-ness. Particularly in discussing language, he talks about how the black person's use of a colonizer's language is seen by the colonizer as predatory, and not transformative, which in turn may create insecurity in the black's consciousness. He recounts that he himself faced many admonitions as a child for using Creole French instead of "real French," or "French French," that is, "white" French. Ultimately, he concludes that "mastery of language [of the white/colonizer] for the sake of recognition as white reflects a dependency that subordinates the black's humanity".

Although Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks while still in France, most of his work was written in North Africa. It was during this time that he produced works such as L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne in 1959 (Year Five of the Algerian Revolution, later republished as Sociology of a Revolution and later still as A Dying Colonialism). Fanon's original title was "Reality of a Nation"; however, the publisher, François Maspero, refused to accept this title.

Fanon is best known for the classic analysis of colonialism and decolonization, The Wretched of the Earth. The Wretched of the Earthwas first published in 1961 by Éditions Maspero, with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. In it Fanon analyzes the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for national liberation. Both books established Fanon in the eyes of much of the Third World as the leading anti-colonial thinker of the 20th century.

Fanon's three books were supplemented by numerous psychiatry articles as well as radical critiques of French colonialism in journals such as Esprit and El Moudjahid.

The reception of his work has been affected by English translations which are recognized to contain numerous omissions and errors, while his unpublished work, including his doctoral thesis, has received little attention. As a result, Fanon has often been portrayed as an advocate of violence (it would be more accurate to characterize him as a dialectical opponent of nonviolence) and his ideas have been extremely oversimplified. This reductionist vision of Fanon's work ignores the subtlety of his understanding of the colonial system. For example, the fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks translates, literally, as "The Lived Experience of the Black" ("L'expérience vécue du Noir"), but Markmann's translation is "The Fact of Blackness", which leaves out the massive influence of phenomenology on Fanon's early work.

For Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, the colonizer's presence in Algeria is based on sheer military strength. Any resistance to this strength must also be of a violent nature because it is the only "language" the colonizer speaks. Thus, violent resistance is a necessity imposed by the colonists upon the colonized. The relevance of language and the reformation of discourse pervades much of his work, which is why it is so interdisciplinary, spanning psychiatric concerns to encompass politics, sociology, anthropology, linguistics and literature.

His participation in the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale from 1955 determined his audience as the Algerian colonized. It was to them that his final work, Les damnés de la terre (translated into English by Constance Farrington as The Wretched of the Earth) was directed. It constitutes a warning to the oppressed of the dangers they face in the whirlwind of decolonization and the transition to a neo-colonialist, globalized world.

An often overlooked aspect of Fanon's work is that he did not like to write his own pieces. Instead, he would dictate to his wife, Josie, who did all of the writing and, in some cases, contributed and edited.

Influences

Fanon was influenced by a variety of thinkers and intellectual traditions including Jean-Paul Sartre, Lacan, Négritude, and Marxism.

Aimé Césaire was a particularly significant influence in Fanon's life. Césaire, a leader of the Négritude movement, was teacher and mentor to Fanon on the island of Martinique. Fanon was first introduced to Négritude during his lycée days in Martinique when Césaire coined the term and presented his ideas in La Revue Tropique, the journal that he edited with his wife, in addition to his now classic Cahier d'un retour au pays natal. Fanon referred to Césaire's writings in his own work. He quoted, for example, his teacher at length in "The Lived Experience of the Black Man", a heavily anthologized essay from Black Skins, White Masks.

Legacy

Fanon has had an influence on anti-colonial and national liberation movements. In particular, Les damnés de la terre was a major influence on the work of revolutionary leaders such as Ali Shariati in Iran, Steve Biko in South Africa, Malcolm X in the United States and Ernesto Che Guevara in Cuba. Of these only Guevara was primarily concerned with Fanon's theories on violence; for Shariati, Biko and also Guevara the main interest in Fanon was "the new man" and "black consciousness" respectively.

Bolivian indianist Fausto Reinaga also had some Fanon influence and he mentions The Wretched of the Earth in his magnum opus La Revolución India, advocating for decolonisation of native South Americans from European influence. In 2015 Raúl Zibechi argued that Fanon had become a key figure for the Latin American left.

Fanon's influence extended to the liberation movements of the Palestinians, the Tamils, African Americans and others. His work was a key influence on the Black Panther Party, particularly his ideas concerning nationalism, violence and the lumpenproletariat. More recently, radical South African poor people's movements, such as Abahlali baseMjondolo (meaning 'people who live in shacks' in Zulu), have been influenced by Fanon's work. His work was a key influence on Brazilian educationist Paulo Freire, as well.

Fanon has also profoundly affected contemporary African literature. His work serves as an important theoretical gloss for writers including Ghana's Ayi Kwei Armah, Senegal's Ken Bugul and Ousmane Sembène, Zimbabwe's Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Kenya's Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Ngũgĩ goes so far to argue in Decolonizing the Mind (1992) that it is "impossible to understand what informs African writing" without reading Fanon's Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon has also influenced the formation in 2013 of a new South African political party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) by the former president of the ANC Youth League, Julius Malema.

The Caribbean Philosophical Association offers the Frantz Fanon Prize for work that furthers the decolonization and liberation of mankind.

Fanon's writings on black sexuality in Black Skin, White Masks have garnered critical attention by a number of academics and queer theory scholars. Interrogating Fanon's perspective on the nature of black homosexuality and masculinity, queer theory academics have offered a variety of critical responses to Fanon's words, balancing his position within postcolonial studies with his influence on the formation of contemporary black queer theory.

Wikipedia

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sidi Brahim

On pourrait penser que je me tourne vers mon passé mais en réalité je recycle de vieux articles jamais publiés car destinés à un public trop restreint. Et pour celui-ci c’est plutôt une refonte totale à partir de textes que j’avais sélectionnés complétés par une recherche plus poussée. Sidi Brahim, ce n’est pas qu’une rue du 4ieme arrondissement de Casablanca ou nous habitions. Curieux de savoir pourquoi le nom a été conservé, j’ai fait des recherches.

Contrairement à ce que je pensais, la rue Sidi Brahim est toujours là

La bataille de Sidi Brahim (Algérie)

Tous les récits que j’ai trouvé relatent la même histoire. Certains sont plus dithyrambiques que d’autres mais tous parlent de la bravoure des soldats. Pourquoi cette hécatombe ? Le colonel Montagnac a-t-il eu une quelconque responsabilité? Le sujet est moins traité.

.-. Le récit de la bataille (source: internet) • Le 21 Septembre 1845, le caïd Trari, chef de la tribu des Souhalia fidèle allié de la France, demanda l’aide et la protection de l’armée française, car menacé par les troupes d’ Abdel Kader. Abdel Kader s’était réfugié au Maroc et avait entrepris de soulever les tribus Algérienne dont beaucoup, s’étaient déjà ralliées à la France. Le Colonel de Montagnac, contrairement aux instructions des généraux, se mit à la tête d’une petite colonne de 60 Cavaliers et 350 Chasseurs avec 6 jours de vivre et partit le jour même à 22 heures. • Le 22 au matin, Trari orienta Montagnac vers le sud. Du bivouac quelques cavaliers Arabes étaient visibles sur les crêtes et eurent lieu les premiers échanges de coups de feu. • Le 23 à l’aube, Montagnac décide de se porter vers les cavaliers ennemis aperçu la veille. Il laisse à la garde du bivouac, le Commandant Froment-Coste, le Capitaine de Géreaux et des éléments de sa compagnie, le Capitaine Burgard et sa 2em Compagnie. Ils font 4 km vers l’ouest et c’est le drame. Surgissant des crêtes environnantes, 5 à 6 000 cavaliers Arabes, menés par Abd el-Kader, fondent sur la petite colonne. Les cavaliers sont submergés et anéantis. Montagnac est tué. La lutte va durée 3 heures. Averti au bivouac le Commandant Froment-Coste se précipite avec la 2em Compagnie vers le combat, situé a 4 km, il ne fera pas 2 km, les Arabes l’interceptent et l’assaillent de toute part. Froment-Coste est tué, le Capitaine Dutertre, Adjudant major est fait prisonnier… Il ne reste qu’une douzaine de Chasseurs. • A 1 km, se dresse le petit édifice de la Kouba du Marabout de Sidi-Brahim. C’est là que Géreaux décide de s’installer, en attendant du secours. Cela n’échappe pas à Abd el-Kader qui pense qu’il va facilement écraser le restes de la colonne Française, mais il va se heurter pendant trois jours et trois nuits à la résistance des 80 Chasseurs du Marabout de Sidi-Brahim. • Dans l’après midi du 23, les Arabes sont en masse autour de la Kouba et c’est le siège, les munitions et les vivres commence à manquer. Un drapeau tricolore est hissé au sommet d’un figuier qui se dresse près du Marabout pour attirer l’attention de la colonne de Barral qui opère non loin, malheuresement la colonne de Barral est attaquée à son tour et s’éloigne dans la plaine. • Les Arabes vont tout faire pour faire céder la résistance inattendue que leur oppose les Chasseurs de la Sidi-Brahim. Par trois fois ils les sommes de se rendre. Après les sommations les sévices. Le Capitaine Dutertre, fait prisonnier le 23, est amené devant la murette et crie à ses camarades : “Chasseurs, si vous ne vous rendez pas, on va me couper la tête. Moi, je vous le dis, faites vous tuer jusqu’au dernier plutôt que de vous rendre”. Quelques instants plus tard, sa tête tranchée est promenée par les Arabes autour de la Kouba. Ce sont alors les prisonniers de combats précédents qui sont traînés de même les mains liées, afin d’ébranler la détermination des hommes. Lavayssière déclenche une fusillade sur l’escorte d’Abd el-Kader qui se trouvait à proximité, et est lui même blessé à l’oreille. • Les jours passent et la résistance ne faiblit pas. Mais les secours n’arrivent pas. Géreaux, blessé et affaibli décide alors, d’essayer de regagner Djemmaa, à près de 15 kilomètres. Le Caporal Lavayssière, prendra le commandement du détachement. • Le 26 Septembre, à l’aube, ils escaladent la face nord de la Kouba, et formés en carré, blessés au centre, ils marchent dans la plaine. L’épreuve va durer toute la journée. Lorsqu’ils parvinrent dans le lit de l’oued Mersa, à 2000 mètres de leur objectif. La tribu des Ouled Ziri les attendait, ce fut un carnage! • Dans la journée du 26 et les jours qui suivent, quelques rescapés de la colonne Montagnac parviendront à rejoindre Djemmaa, mais plusieurs succomberont à leur épuisement et à leurs blessures.

.-. Montagnac • Le lieutenant-Colonel Montagnac, s’est lancé dans cette bataille sans préparation, sans plan, sans informations sur l’ennemi qu’il allait affronter, sa seule idée était la capture de l’émir Abdel Kader. Et contre l’avis de ses chefs. • Après un premier combat, les troupes françaises furent réduites de 450 à 82 chasseurs qui se réfugièrent dans un marabout d’où ils repoussèrent tous les assauts. • Après plusieurs jours de siège, les hommes, sans eau, sans vivres, à court de munitions, en furent réduits à couper leurs balles en morceaux pour continuer à tirer. L’émir Abd El Kader fit couper la tête du capitaine Dutertre, fait prisonnier et amené devant le marabout pour exiger la reddition des chasseurs. Malgré tout, Dutertre, eut le temps d’exhorter les survivants à se battre jusqu’à la mort. • Les survivants, n’ayant plus de munitions, chargèrent à la baïonnette. Ils percèrent les lignes ennemies et, sur les 80 survivants, 16 purent rejoindre les lignes françaises et 5 moururent quelques jours plus tard. Seuls 11 chasseurs sortirent vivants de la bataille.

.-. Le lieutenant-colonel de Montagnac 15 mars 1843: « Anéantir tout ce qui ne rampera pas à nos pieds comme des chiens. » (Algérie) Lettres d’un soldat, Plon, Paris, 1885.

.-. Le monument commémorant Sidi Brahim • Un premier monument est inauguré le 26 décembre 1898 à Oran en Algérie. Il est composé d’un obélisque de huit mètres de haut couronné d’une figure ailée, une Gloire, placée au sommet du monument. Au-dessous, contre le piédestal, une statue de femme agenouillée symbolisant la France écrivant sur la stèle, “Camarades, défendez-vous jusqu’à la mort” et, au premier plan, le Soldat mortellement blessé ainsi qu’une plaque en bronze portant l’inscription, “Aux héros de Sidi-Brahim, 1845”.

• En 1962 la femme agenouillée: la France, est déboulonnée et remplacée par un buste de Abdel Kader. La gloire est restée au sommet de l’obélisque. • La France de Dalou se trouve aujourd’hui en France, à Périssac dans le vignoble bordelais. Périssac, commune natale du capitaine Oscar de Géreaux, l’un des martyrs de Sidi-Brahim. Le monument de Sidi-Brahim a fêté ses cinquante ans en 2016. Il a été inauguré le 10 juillet 1966.

.-. Donc le nom a été conservé • soit parce qu’il correspond à une défaite de l’armée coloniale française mais c’était en Algérie, • soit tout simplement parce qu’il a une consonnance arabe. Allez savoir! • Après avoir beaucoup lu sur cette bataille et le fait qu’elle soit encore dans les mémoires je pencherais pour la première hypothèse.

https://www.sudouest.fr/2016/09/23/le-monument-de-sidi-brahim-fete-ses-cinquante-ans-2510774-2780.php

Toutes les Photos sont là : https://photos.app.goo.gl/6vT6fPUviqeAVeC76

#gallery-0-6 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-6 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

http://bit.ly/ChristianLoverde

Sidi Brahim Sidi Brahim On pourrait penser que je me tourne vers mon passé mais en réalité je recycle de vieux articles jamais publiés car destinés à un public trop restreint.

0 notes

Text

Vidéo: Casablanca: Ain Diab, la plus célèbre corniche du <b>Maroc</b>, comme vous ne l'avez jamais vue

Morocco Mall, Anfa Place, Mégarama, le Marabout Sidi Abderrahmane, restaurants et cafés, tout est aujourd'hui sans vie à Ain Diab. Vidéo. Coronavirus ... source https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://fr.le360.ma/societe/video-casablanca-ain-diab-la-plus-celebre-corniche-du-maroc-comme-vous-ne-lavez-jamais-vue-212007&ct=ga&cd=CAIyHGZjOGY3YTdmOWE3MjBhYTI6Y29tOmZyOlVTOkw&usg=AFQjCNGaRcsnbEDkXljv6utBCckurRR1lA

0 notes

Photo

My other band...

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

0 notes

Photo

To katter, tre geiter og en gutt som sitter på en stol uten ben på en klippe

0 notes

Photo

0 notes

Photo

0 notes