#lucy's really out there living her forest nymph fantasies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

🫐 — wild blueberries! for a headcanon about my muse and a time they have had to, or decided to, forage for /go picking wild fruits and vegetables.

Lucy definitely prefers fresh picked fruits and veggies over store bought ones, but she's never really foraged for wild ones. She would normally go to farmer's markets or farms that allow you to pick them yourself for her produce needs.

In her main main verse, she and Gunpowder live in the middle of the woods, and she's basically turned their little cabin into a farm. She has a bunch of farm animals that she's brought home, and he's built barns and pens for the animals. They've cleared out a space for their garden where she grows her flowers, but they also grow their own produce as well. She's never really had a need to forage.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Narnia Re-read of 2019: “Prince Caspian”

The Chronicles of Narnia

Of all the Chronicles, Prince Caspian turned out to be the one I’d most forgotten. Possibly because I love the 2011 movie so much (which brushed over a good portion of the book), large parts of it read like new to me. The movie leaves out the book’s most strident theme, which is what I want to talk about.

Theme: The Re-Creation of Narnia

Revival is the theme of Prince Caspian. The Narnia that had been redeemed by Aslan’s sacrifice and the Pevensies’ coronation was a distant memory. It was more myth to some like Nikabrik and even Trumpkin. The land was dead. The trees slept. The gods were dormant. The realm had been taken over by Telmarines who both hated Old Narnia and feared it. They rejected magic, regarded Narnia’s natives as abominations, and lived in a desperate and pitiful abhorrence of the Eastern Sea and the Lion who was always said to come from across it.

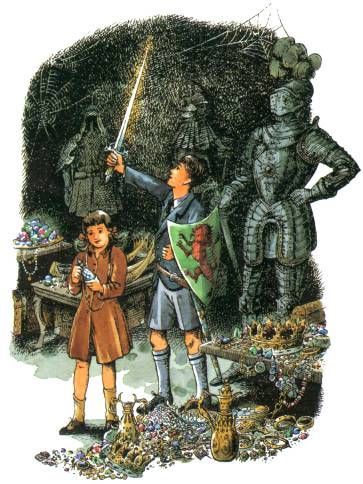

The old kings and queens land in Narnia.

When I think of dead Narnia under Telmar’s rule, I can’t help but think of all the times I’ve heard laments about “dead” churches—churches with no spirit or life. I can’t help but think of all the desperate prayers for revival and all the “revival meetings” held in pursuit of that which they claimed to be.

Of course the Telmarines, who styled themselves true Narnians, did not want revival. They didn’t know exactly what revival would mean, except that it would involve the awakening of the trees and the return of the Lion.

But when Aslan arrives, he does not immediately round up the trees and lead them against the Telmarines in support of Caspian’s tired army (as he did for Peter in his battle against the White Witch’s forces). Instead, once the trees are awake, he declares that it is long past time for a party. Thus begins a night and a day of singing, dancing, revelry, feasting, drinking, merry-making, and story-telling, with Aslan at its very center. Hours and hours of sheer unmitigated joy are followed by the magic-drunk partiers dropping off to sleep in a forest clearing. The details of the celebration are too varied and meticulous to recount here.

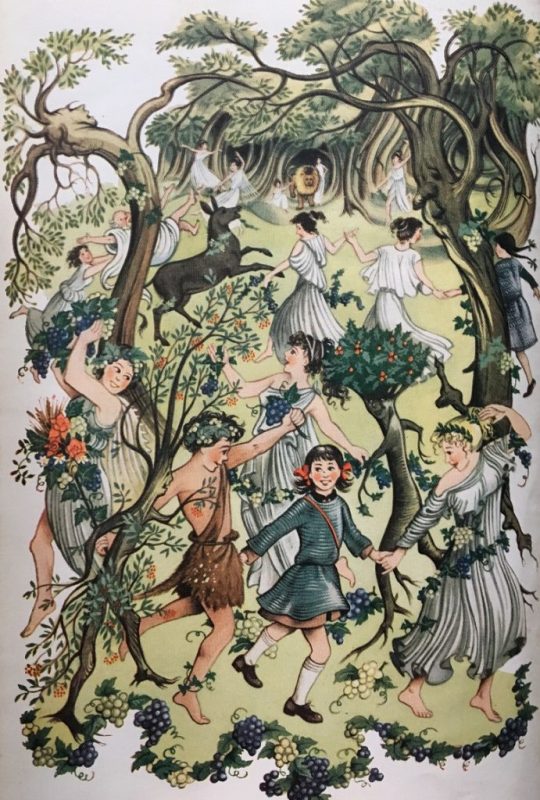

The crowd and the dance round Aslan (for it had become a dance once more) grew so thick and rapid that Lucy was confused.

“Is it a Romp, Aslan?”

Apparently it was. But nearly everyone seemed to have a different idea as to what they were playing.

…all of a sudden everyone felt at the same moment that the game (whatever it was), and the feast, ought to be over, and everyone flopped down breathless on the ground and turned their faces to Aslan to hear what he would say next.

The revival, having starting with Aslan’s roar, reminds one of Narnia being called into creation by Aslan’s song. “The sound, deep and throbbing at first, like an organ beginning on a low note, rose and became louder, and then far louder again, till the earth and air were shaking with it. It rose up from that hill and floated across all Narnia.” As the call rang out, the trees, the animals, the river-god, the nymphs awakened, remembering how Aslan had called them into being. This is a true revival—not merely an awakening of the old, but a renewing—a reset—a Re-creation.

“We will make holiday,” Aslan declares.

“Aslan’s Romp,” by Pauline Baynes

When morning comes, Aslan sets about the work of putting things to right in Narnia. Aslan’s work, once again, is not aiding Caspian, Peter, and Edmund in their desperate negotiations (and later duel) with the despot Miraz. The “work” is freeing a bunch of girls from their stuffy school, freeing a teacher from her miserable duties, breaking down the Bridge of Beruna, turning a child abuser into a tree, breaking the chains of dogs, freeing horses from their burdens, making old donkeys young again, and healing a half-dwarf who turns out to be Caspian’s nurse. Along the way, “everyone was laughing, flutes were playing, cymbals clashing. Animals were crowding in upon them from every direction.” Silenus is (drunk?) on his donkey. Bacchus, draped in vines, is leading a troop of madcap dancing girls.

No matter the outcome, this duel won’t save Narnia.

It seems like insanity. (Of course, some of it is wish-fulfillment for Lewis who saw the encroachment of industrialism, practical science, and modernism in education as problematic for various reasons. Hey, if you can’t torch it in real life, you can torch it in your fantasy novel.) But while Peter and Caspian were fighting to restore Narnia’s political regime, Aslan was restoring Narnia’s soul. His work was more important. What good would it have been for Caspian to be crowned king and the Old Narnians allowed to live freely, if the trees still slept, magic remained dead, and the spirits and gods that gave Narnia its unique vitality remained in exile?

Looking at society today, there is a sense of the same struggle. Conservative religious types want a return to an idealized earlier era where the government, by their account, was in lockstep with the church (or one faction of the church). Liberal anti-religionists think their anger and rancor are all that is needed to force change and bring about a just, fair, and equitable society. Either side could achieve their goal at the expense of the other, but the outcome would leave a heartless, joyless society, devoid of true celebration. The outcome of such battles cannot result in true revival.

True revival begins, not on the battlefield (whether literal or metaphorical), but on the playground and around the dining table and in living rooms. Revival begins when our hearts reawaken to the old ways we seem to have forgotten: the ways of neighborliness and friendship, of feasting and frivolity, of story-telling and community, of laughter and love and longing fulfilled, of dance and delight in simple things.

Impossibly, after centuries of repression, that’s how Narnia was restored.

The Great Bridge Builder approves of the destruction of the Bridge of Beruna.

The Telmarines feared that which they could not control—the wild, impossible magic of the land they had conquered. So they tried to stamp it out. They walled themselves off from it. They let their fear drive out magic and love, and so became a cruel and heartless people.

That’s the way our world is going. We’re letting fear drive out love and dreams and simple things. Fear of the other. Fear of open doors and open hands. Fear of the possibilities. And if we succumb to fear, we wall ourselves off from love and magic—things which no law, no election, no regime change can restore.

Our only hope is revival—recreation—in the way Aslan brings it: a tidal wave of unrepressed and exuberant charity expressed through friendship and feasting, the breaking of chains, the correcting of injustices, care for nature, and the righting of wrongs wherever they are found. Only then will we reawaken joy and magic and general happiness and peace.

Prince Caspian: A Parallel of the Apostle Paul?

Prince Caspian on the Road to Damascus

Years ago, shortly after reading Prince Caspian and watching the movie, I was reading through the Book of Acts. I don’t remember how far along I was in the book—but it must have been more than halfway—when it jumped out at me: oh my gosh, Prince Caspian is the story of the Apostle Paul; everything lines up!

Due to the common misconception of what an allegory is, people often mistake The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe as being such. It is, in fact, as Lewis called it, “a supposition”—similar to the modern fantasy-genre retellings of classic fairy tales and myths that have become popular of late. They answer the question: How would this have happened in another world or another time? I think, whether Lewis intended it or not, Prince Caspian is that kind of story—a supposition of what the aftermath of Jesus’ resurrection would have looked like in Narnia. (Obviously, I’m ignoring the time difference between Jesus’ resurrection and the events of the Book of Acts in our world and Aslan’s resurrection and Prince Caspian’s time in Narnia.) The rough approximations look like this:

Prince Caspian tries to convince the Old Narnians he’s not like the rest of the Telmarines.

The Old Narnians represent the first century believers.

The Telmarines represent the Jewish religious authorities who tried to stamp out, sometimes violently, the sect of the Nazarene.

The Pevensies represent the original apostles of Christ who accept, confirm, and aid Caspian in his new journey as a follower of Aslan.

Caspian, destined (at one time) to be a standard bearer of the persecution of Old Narnia, reminds me of Saul who, as part of the Jewish religious establishment, “breathed out threatenings and slaughter” against the followers of the Way.

Caspian’s flight from the Telmarine stronghold and his subsequent run-in with Trumpkin, Nikabrik, and Trufflehunter is his Damascus Road experience.

And just as the believers were suspicious of Saul (later to become known as Paul) and his sudden conversion, many of the Old Narnians are suspicious of Caspian appearing to be on their side.

There you have it. It seemed so apparent to me that I was sure others had thought similarly. But I’ve searched the internet and, alas, it seems I’m the only one.

The Movie

As indicated at the beginning of this piece, I really like the 2011 Prince Caspian movie adaptation. It was gritty, earthy, and lived up to its trailer tagline: “You’ll find Narnia a more savage place than you remember.” I even liked the realistic head-butting between Peter and Caspian and the teasing romance of Caspian and Susan. (The kiss at the end was overkill. When that appeared on the big screen, I, like I’m sure many others, thought, Hey! You have to explain that to Ramandu’s daughter one day.)

But the thing I liked the most was the variety of Old Narnian creatures present at Aslan’s How and in the midnight raid on the Telmarine fortress. Centaurs, mice, satyrs, fauns, dwarfs, gryphons, kid centaurs (centaurlings?), lady centaurs, squirrels, bears, giants. Did I say mice? I loved it.

Good old Narnians

There was one glaring flaw in the movie that I thought, if done away with, would have made a stronger cinematic experience. (Not that anyone cares at this point; but I like carrying on about the mechanics of storytelling whether literary or visual, so bear with me.)

One of these things is not a Pevensie.

From the book, I got the impression that Caspian was about Edmund’s age. However, in the movie, he appears to be older than Peter and is bigger (taller) than all of the Pevensies. The movie tries to play Caspian as a vulnerable, threatened heir to the throne—someone who needs the Pevensies’ help. But it’s hard to believe. You can sense Barnes as Caspian holding back out of deference—when what you should feel is his desperation. This is shown distinctly in a scene close to the end of the movie: after the Telmarines have surrendered, Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Caspian kneel before Aslan. Caspian’s head levels above the Pevensies’, automatically drawing your eye to him. And when the Pevensies rise and Caspian remains kneeling, the result is almost comical: the viewer’s mind says, “one of these things does not belong,” and the scene tries to force you to accept that Caspian ��belongs.”

A younger (shorter) actor would not have stuck out so obviously in this scene. Throughout the movie, by virtue of his youth, he would have appeared more authentically vulnerable and threatened—someone who needed help, someone who would have more easily taken advice. And, he wouldn’t have towered over Trufflehunter and Nikabrik in that run through the forest as they were trying to get away from the Telmarine soldiers.

Can you feel those “vulnerable prince” vibes? …Didn’t think so.

To be clear, I like Ben Barnes. I think he did a great job portraying Caspian. But there was a bit of cognitive dissonance when he appeared with the Pevensies on screen. (That accent didn’t help either.)

Go to the article

0 notes