#literature student wilhelm Is so canon and so real

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

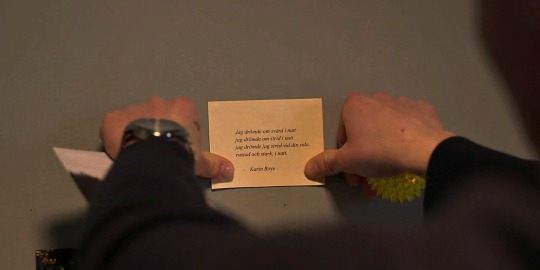

"I dreamt of swords last night.

I dreamt of battles last night.

I dreamt I fought by your side

armed and strong, last night."

#young royals#wilmon#prince wilhelm#simon eriksson#we don't talk about this scene enough#literature student wilhelm Is so canon and so real

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cast of Mignon: reality check

(apologies in advance if none of this makes sense. It’s a pretty obscure opera.)

Mignon (Sperata), mezzo-soprano

Mezzo heroines for the win! Gets a relatively famous mezzo aria (”Connais-tu le pays”) Here portrayed as older than her literary counterpart, but still unfortunately in love with one of the biggest jerks in opera and literature in general (sorry not sorry Goethe). Canonically genderfluid because Barbier and Carré are awesome. She deserves much more than what this world throws at her (including Wilhelm) and unfortunately her naivete is probably what leads her to believe she doesn’t have the ability to seek out better things. If she were given the chance to explore the world and gain experience outside her former captivity (and Wilhelm), she would be better able to make smarter choices. Aside from this general misfortune, she is extremely sweet and adorable, altogether too accommodating (a trait that literally almost gets her killed). She should have gone off with Lothario after he adopts her, like he asked her to, and the two of them could have travelled to her homeland and made the discovery of their relation without Wilhelm. Also, she should totally date Frédéric. Although getting together with Wilhelm isn’t the ideal happy ending, she does find her father and her home and her real name (Sperata). It’s unfortunate we had to wait three hours to be able to call her that.

Wilhelm, tenor

A student. Classic example of the Dick Tenor. Basically wants to roam the world without commitments or consequences, which truthfully is relatable; but when it’s at the expense of the well-being of people in your life, it’s not really fair. He is decently nice to Mignon, taking care of her when she starts following him around and when she gets sick. However, the fact that he only starts to fall for her when she presents as feminine is unfair and tbh kinda gross. He does not heed the warnings of Laerte, who (as seen below) has gotta win some kind of record for tenor braincells. Wilhelm is totally smitten with Philine because of her charm and her fame; we can’t really blame him for that, since pretty much everyone is. And yeah, he does risk his life to save Mignon. Still doesn’t save his dick personality, though. Overall he just needs an attitude adjustment, a splash of reality, and probably a good slap in the face. (Sorry, I just really do not like Wilhelm.)

Lothario, bass

A wandering musician. Genuine Good Bass. Traditional operatic adopted father figure, but in this case, it just so happens that the child he rescues and adopts actually is his kid. This isn’t discovered until the end, though. He’s clearly traumatized, and of course society interprets this as him having lost his mind. He turns to music for comfort. Constantly searching for the thing he has lost, but he can’t remember what that is. Primarily only interacts with Mignon, whom he tries to protect from the rest of the world. Unfortunately he is also very suggestable, which leads to the unfortunate incident of Philine’s theater getting burned down when Mignon wishes a fiery death on her rival. Once he rediscovers his identity as both Mignon’s father and a nobleman, it’s clear he’s going to put these roles to good use and make the world a better place. Now if only he’d have the sense to kick Wilhelm out.

Philine, soprano

A singer and actress. Thing is, Philine would probably be more of a halfway decent person if she weren’t infatuated with Wilhelm. After all, she is the one who paid for Mignon’s freedom, and in the extended ending she has a moment where she almost apologizes. Plus, the biggest mean thing she does wasn’t meant to be life-threatening for those involved, and she only did it because she was jealous of the attention Wilhelm was giving Mignon. Another case of sopranos losing brain cells around tenors. In general, she’s still a vain, self-centered drama queen. We can understand her desire to live life to the fullest; if only it weren’t at the expense of those around her. Truthfully, she and Wilhelm are probably a better match for each other than the (operatic) canon couple, because of their mutual obliviousness to the needs of others and their similarly self-absorbed attitudes. In the original (extended) ending, she does say she’s going to get together with Frédéric, but for his sake, let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

Laerte, tenor

An actor in Philine’s troupe. Plays the role of Genuinely Good Tenor since Wilhelm can’t be bothered to. Probably the smartest person in this opera. He sees what everyone else refuses to see and tries to be practical, but that’s hard when you’re surrounded by oblivious lovebirds. Primary function is to provide sarcastic commentary. Has a delightful little number where he teases Philine. Tries to warn Wilhelm against falling for Philine, but of course Wilhelm doesn’t listen. Laerte clearly feels for both Mignon and Frédéric. However, he has basically given up on trying to interfere in other people’s lives. Why he continues to follow Philine around is anyone’s guess. He probably just enjoys observing the drama that consistently surrounds her.

Frédéric, mezzo, is absolutely never a tenor because that would be ridiculous

One of the most adorable and underrated trouser roles in opera. As per usual, very much crushing on the soprano and jealous of her affections for the tenor. Has an absolutely delightful number when he sneaks into Philine’s room. Draws his sword on Wilhelm as a challenge when they find they’ve each snuck in to meet Philine in her room. Wilhelm clearly does not take him seriously. Pretty much no one does, in fact. He does laugh at Mignon when he sees her in a dress, which isn’t very nice, especially given her self-esteem is almost nonexistent to begin with. He’d probably gain a few brain cells if he gave up on Philine. It’s insinuated at the end (in the original ending, at least) that he does, in fact, wind up with Philine. However, I’m still in camp Mezzos Should Run Off Together, and I think if Frédéric lets go of his obsession with Philine, and Mignon lets go of her obsession with Wilhelm, the mezzos could totally get together.

Jarno, bass

Functional purpose is to be the one who kidnapped Mignon and eventually sells her to Wilhelm (who sets her free), but is also a really insulting portrayal of stereotypes surrounding Romani people, which isn’t entirely the librettist’s fault because it’s based on the original source material, but still, Barbier and Carré could have done better. But this opera is pretty messed up in general. They probably should have just picked a different story.

#this opera is kind of obscure#and very odd tbh#i keep giving past me a side-eye bc it was my favorite opera for a significant amount of time#to be fair the music IS incredible#but it's the only time i've been disappointed in Barbier and Carré#i mean it could be worse but#it could also be better#and not necessarily just in that stereotypical operatic trope-y way#there are certain aspects of the story that aren't that#maybe kinda just products of their time but#not just that either#i partially blame Goethe#but at least Mignon doesn't DIE like she did in the books#also i still do not understand why Wilhelm is such a belvoed character#he's such a jerk#like for real#one of the jerkiest tenors i've encountered#not like specifically evil just#really inconsiderate and unworthy of the infatuation he receives#still trying to come up with a tenor i wouldn't feel bad putting in this role for my fantasy cast#anyway#Mignon#Mignon opera#Ambroise Thomas#Jules Barbier#Michael Carré#opera#opera tag#opera characters#opera analysis

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Garth Greenwell Wants Us to Stop Policing What Stories Are ‘Relevant’

Published by Medium

His new novel ‘Cleanness’ challenges what it means for a story to be ‘universal’

In 2014, when Garth Greenwell was an MFA student at The Iowa Writers’ Workshop, a professor he revered — “and continue[s] to revere,” he says — dismissed a short story he’d written about cruising for sex, saying that it “read like a sociological report on the practices of a subculture.” Greenwell was shocked, in part because the critique seemed to pivot on a loaded question: What makes a piece of art “universal”?

“To this professor, something like Congregationalist ministers in rural Iowa” — as Marilynne Robinson explores in her novel Gilead — “did not feel like a subculture, but instead was representative of universal human experience,” says Greenwell “in a way that gay men having sex with each other in a bathroom did not.” He has been writing urgently against that proposition for his entire career — including in his sophomore novel, Cleanness, out January 14.

Greenwell’s 2016 debut novel What Belongs To You was critically celebrated, winning the British Book Award for Debut Book of the Year and longlisted for the National Book Award. It opens with a man cruising for sex in a public bathroom in Bulgaria, beneath Sofia’s National Palace of Culture. The novel is told from the perspective of an American abroad, an unnamed English teacher who pays for sex with a hustler named Mitko. That transaction sparks a murky relationship rooted in profound inequities, providing a particular lens into the politics of contemporary Bulgaria as it stumbles out of its recently communist past. It also urges the narrator to examine how growing up gay in the South informs his current relationship to desire, shame, and belonging.

Cleanness is a kind of sequel to What Belongs to You, finding the American abroad in a more conventional relationship, with a Portuguese exchange student he refers to as R. Greenwell once again examines the pageantry of sexual dominance and submission with frank, tensile precision. “I was interested in how we use the idea of cleanliness as a concept,” he says over the phone from Iowa, where he’ll teach a fiction course at the Writers’ Workshop this spring. In chat rooms, for instance, “Are you clean?” is a way of asking prospective partners about their HIV status. Greenwell had come to regard cleanliness as a “devastating ideal.” Before he was a novelist Greenwell studied poetry; the word “cleanness” is an allusion to a medieval poem written in the late 14th century that interprets the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, or what Greenwell calls “the nightmare version of cleanness.”

“It does seem to be a fact of human life that we long both to be clean and to bathe in filth,” he says. “And what I hope the book leads to or suggests by the end is the possibility of a life that can accommodate both urges in a way that doesn’t require the eradication of a huge chunk of ourselves or our desires.”

Greenwell belongs in the ever-evolving canon of gay literature, a canon that has significantly expanded since he discovered queer writers like James Baldwin and Jeanette Winterson in his youth. He found their work “lifesaving,” allowing him to reject the presumption that the “only possible shapes for my life were being a child molester and dying of AIDS.”

Some might find it limiting to be thought of as a “gay writer” writing “gay fiction.” But Greenwell accepts the designation. Instead of constricting his work, he considers it a key part of its expansion. “Art achieves universality through devotion to the particular,” he says. “My serious, firmly held belief about art is that any human experience can open the door to all human experience.”

Greenwell has been ruminating on the concept of “relevance” lately, particularly as the word gets thrown around on Twitter, as a colloquial and often catty form of critical discourse. In writing about gay sex, he himself somewhat benefits from the current hunger for stories from underrepresented voices. Other writers find themselves out of vogue. Greenwell recalls hanging out with his friends at Prairie Lights, his local bookstore in Iowa City, and casually shooing away a novel based on its jacket copy: “Do we really need another story about a middle-aged guy who’s thinking about cheating on his wife?”

But he rejects his own impulse to dismiss the book in question. “That is as false as what that professor at that writing workshop said to me,” says Greenwell, calling such judgments “anti-art.”

Greenwell, 41, lives in Iowa City with his partner, the poet Luis Muñoz, who runs the Spanish MFA program at the University of Iowa. Though he admires Iowa City’s rich literary history and its self-awareness as a city of literature, he finds it a difficult place to write. In cafes, he can often feel the novels being constructed around him. Greenwell instead prefers the solitude he found in Bulgaria, where, like his protagonist, he moved to teach at the American College of Sofia in 2009. It was there, feeling completely disconnected from the literary world, that he first started writing fiction, drafting what would eventually become What Belongs To You.

In Iowa, Greenwell often tries tricking himself back into that literary isolation. It’s partly why he writes his books longhand rather than on the computer, where the rest of the world feels too close.

“I really do experience making art as failure,” he says. “I have a very highly developed sense of humiliation, and for me to feel comfortable failing in the way I need to fail in order to write anything that’s meaningful to me, I need to feel like no one knows what I’m doing, [like] no one cares what I’m doing.”

Greenwell calls Cleanness a book of fiction, rather than a novel or story collection. He sees its nine sections as a song cycle, or “nine centers of emotional intensity that are set in relation to one another,” he says. He modeled the structure of the book after Schubert’s “Winterreise,” the 1828 song cycle for piano and voice set to poems by Wilhelm Müller.

Music was Greenwell’s first education in art. As a high school student in Kentucky, he failed his freshman year of English — in part because his father had kicked him out of the house for being gay at age 14. Singing provided temporary solace. His choir teacher recognized something in Greenwell’s voice and introduced him to opera, giving him private voice lessons after school. At the end of his freshman year he handed Greenwell an application to Interlochen Center for the Arts, an arts boarding school in Northern Michigan.

“He knew that I was really kind of having suicidal sex. I was just so extravagantly promiscuous and unsafe in the parks of Louisville, and I think he was the one adult who saw this kid was really in trouble,” says Greenwell. “He was the first person, certainly the first adult, who suggested that my life might have any value.” Transferring to Interlochen on a scholarship his sophomore year and escaping the turmoil of his family life was like “flipping a switch” and he went from nearly failing to being an A student.

Though he transitioned from opera to poetry while in college, at the University of Rochester, Greenwell says opera bears a greater influence on his writing than the novel, informing his expansive, experimental approach to syntax — “singing opera is often using very few words over a long period of time” — and the suspension of his prose. “When I’m writing, I never think of other writer’s sentences,” he says. “I think about music. The shape I’m writing into is the shape of Jessye Norman singing a phrase of Strauss’s Four Last Songs.”

Is the work of Richard Strauss, the German composer born in 1864, “relevant” today? Perhaps in so far as it helps Greenwell to create work that aspires to be “urgently communicative” in 2020. “In my experience of art I often feel that I’m being called to tune myself to a particular pitch,” he says.

Relevance, as Greenwell sees it, also has nothing to do with popularity. He calls such preoccupations “the death of an artist.” With the release of Cleanness looming, he’s not indifferent to book sales. “I would love if I could pay for my house,” he says. “But I hope that I never have the false idea that whether my book sells a million copies or 10 copies has anything to do with the actual artistic value of that book.” Those numbers have so much to do with chance, subject to the vagaries of a fickle publishing industry.

Instead, Greenwell’s true mark of success is clear: “When a 15-year-old kid in Kentucky pulls Giovanni’s Room from a library shelf — that’s the real life of literature.”

0 notes