#like we already have scenes of him mingling with artists and painters and their models and boxers and modistes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

you know what we need for benedict's season is genuine yearning pining longing unable to touch forbidden scandalous not only on a societal level but on a class level romance vibes. i need that man to not be able to LOOK at sophie in case the wrong people see. i want him utterly unable to speak to her or interact with her in any meaningful way because the slightest wrong move might ruin her entirely. benedict is the least repressed bridgerton sibling by a long chalk, and i want him to Suffer bc his usual method of immediately hooking up with any person he finds even mildly attractive is completely off the table in this scenario. i want him to have to fight himself every moment to keep his distance i want him to be in abject agony i want him to truly Yearn hopelessly!! they need to not touch for like at least six episodes and when they finally do i need benedict to immediately pass out

#bridgerton#benedict bridgerton#does this fit with the book? not really. but the show is already so different that i'm kinda hoping they change some of his story's themes#bc i don't think show!benedict would ever ask a woman to be his mistress it just doesn't feel like he has those vibes#he already doesn't really care what society thinks of him so i can't see him being too cut up about sophie's parentage or status#like we already have scenes of him mingling with artists and painters and their models and boxers and modistes#and he's always perfectly at ease wherever he goes. which i think is part of the reason show!benedict is such a scene stealer#luke thompson really plays him with such a level of ease and familiarity that u don't see in many of the others#it truly feels like he's part of the family. he makes every scene his own in subtle ways and it's really fascinating#anyway if his season isn't next i'm gonna riot they can't keep theatrically trained luke thompson away from a real storyline for any longer

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

LORNA SIMPSON

Lorna Simpson, The Water Bearer (1986)

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/02/arts/design/02lorn.html

Lorna Simpson, Guarded Conditions (1989)

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/representing-the-black-body-lorna-simpson-in-conversation-with-thelma-golden-54624

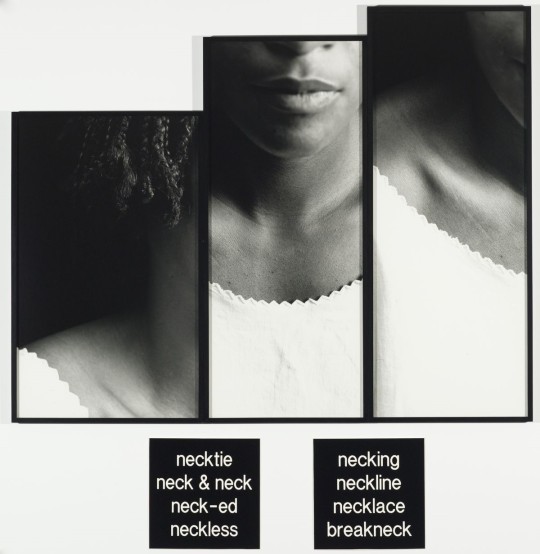

Lorna Simpson, Necklines (1989)

https://mcachicago.org/Collection/Items/1989/Lorna-Simpson-Necklines-1989

Lorna Simpson Wigs (1994)

https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/lorna-simpson-wigs-1994/

Childhood

Born in Brooklyn in 1960, Lorna Simpson was an only child to a Jamaican-Cuban father and an African American mother. Her parents were left-leaning intellectuals who immersed their daughter in group gatherings and cultural events from a young age. She attributed their influence as the sole reason she became an artist, writing, "From a young age, I was immersed in the arts. I had parents who loved living in New York and loved going to museums, and attending plays, dance performances, concerts... my artistic interests have everything to do with the fact that they took me everywhere ...."

Aspects of day-to-day life lit up Simpson's young imagination, from the jazz music of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, to magazine advertisements and overheard, hushed stories shared between adults; all of which would come to shape her future art. The artist took dance classes as a child and when she was around 11 years old, she took part in a theatrical performance at the Lincoln Center for which she donned a gold bodysuit and matching shoes. Though she remembered being incredibly self-conscious, it was a valuable learning experience, one that helped her realize she was better suited as an observer than a performer. This early coming-of-age experience was later documented in the artwork Momentum, (2010).

Simpson's creative training began as a teenager with a series of short art courses at the Art Institute of Chicago, where her grandmother lived. This was followed by attendance at New York's High School of Art and Design, which, she recalls "...introduced me to photography and graphic design."

Early Training and Work

After graduating from high school Simpson earned a place at New York's School of Visual Arts. She had initially hoped to train as a painter, but it soon became clear that her skills lay elsewhere, as she explained in an interview, "everybody (else) was so much better (at painting). I felt like, Oh God, I'm just slaving away at this." By contrast, she discovered a raw immediacy in photography, which "opened up a dialogue with the world."

When she was still a student Simpson took an internship with the Studio Museum in Harlem, which further expanded her way of thinking about the role of art in society. It was here that she first saw the work of Charles Abramson and Adrian Piper, as well as meeting the leading Conceptual artist David Hammons. Each of these artists explored their mixed racial heritage through art, encouraging Simpson to follow a similar path. Yet she is quick to point out how these artists were in a minority at the time, remembering, "When I was a student, the work of artists from varying cultural contexts was not as broad as it is now."

During her student years Simpson travelled throughout Europe and North Africa with her camera, making a series of photographs of street life inspired by the candid languages of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Roy DeCarava. But by graduation, Simpson felt she had already exhausted the documentary style. Taking a break from photography, she moved toward graphic design, producing for a travel company. Yet she remained connected to the underground art scene, mingling with likeminded spirits and fellow African Americans who felt the same rising frustrations as racism, poverty, and unemployment ran deep into the core of their communities.

At an event in New York Simpson met Carrie-Mae Weems, who was a fellow African American student at the University of California. Weems persuaded Simpson to make the move to California with her. "It was a rainy, icy New York evening," remembers Simpson, "and that sounded really good to me." After enrolling at the University of California's MFA program, Simpson found she was increasingly drawn towards a conceptual language, explaining how, "When I was in grad school, at University of California, San Diego, I focused more on performance and conceptually based art." Her earliest existing photographs of the time were made from models staged in a studio under which she put panels or excerpts of text lifted from newspapers or magazines, echoing the graphic approaches of Jenny Holzer and Martha Rosler. The words usually related to the inequalities surrounding the lives of Black Americans, particularly women. Including text immediately added a greater level of complexity to the images, while tying them to painfully difficult current events with a deftly subtle hand.

Mature Period

Simpson's tutors in California weren't convinced by her radical new slant on photography, but after moving back to New York in 1985, she found both a willing audience and a kinship with other artists who were gaining the confidence to speak out about wider cultural diversities and issues of marginalization. Simpson says, "If you are not Native American and your people haven't been here for centuries before the settlement of America, then those experiences have to be regarded as valuable, and we have to acknowledge each other."

Simpson had hit her stride by the late 1980s. Her distinctive, uncompromising ability to address racial inequalities through combinations of image and text had gained momentum and earned her a national following across the United States. She began using both her own photography and found, segregation-era images alongside passages of text that gave fair representation to her subjects. One of her most celebrated works was The Water Bearer, (1986), combining documentation of a young woman pouring water with the inscription: "She saw him disappear by the river. They asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory." Simpson deliberately challenged preconceived ideas about first appearances with the inclusion of texts like this one. The concept of personal memory is also one which has become a recurring theme in Simpson's practice, particularly in relation to so many who have struggled to be heard and understood. She observes, "... what one wants to voice in terms of memory doesn't always get acknowledged."

In the 1990s Simpson was one of the first African American women to be included in the Venice Biennale. It was a career-defining decade for Simpson as her status grew to new heights, including a solo exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1990 and a series of international residencies and displays. She met and married the artist James Casebere not long after, and their daughter Zora was born in the same decade. In 1994 Simpson began working with her grandmother's old copies of 1950s magazines including Ebony and Jet, aimed at the African American community. Cutting apart these relics from another era allowed Simpson to revise and reinvent the prescribed ideals being pushed onto Black women of the time, as seen in the lithograph series Wigs (1994). The use of tableaus and repetition also became a defining feature of her work, alongside cropped body parts to emphasize the historical objectification of Black bodies.

Current Work

In more recent years Simpson has embraced a much wider pool of materials including film and performance. Her large-scale video installations such as Cloudscape (2004) and Momentum (2011) have taken on an ethereal quality, addressing themes around memory and representation with oblique yet haunting references to the past through music, staging, and lighting.

Between 2011 and 2017 Simpson reworked her Ebony and Jet collages of the 1990s by adding swirls of candy-hued, watercolour hair as a further form of liberation. She has also re-embraced painting through wild, inhospitable landscapes sometimes combined with figurative elements. The images hearken to the continual chilling racial divisions in American culture. As she explains, "American politics have, in my opinion, reverted back to a caste that none of us want to return to..."

Today, Simpson remains in her hometown of Brooklyn, New York, where in March 2020, she began a series of collages following the rise of the Covid-19 crisis. The works express a more intimate response to wider political concerns. She explains, "I'm just using my collages as a way of letting my subconscious do its thing - basically giving my imagination a quiet and peaceful space in which to flourish. Some of the pieces are really an expression of longing, like Walk with Me, (2020) which reflects that incredibly powerful desire to be with friends right now."

Despite her status as a towering figure of American art, Simpson still feels surprised by the level of her own success, particularly when she compares her work to those of her contemporaries. "I feel there are so many people - other artists who were around when I was in my twenties - who I really loved and appreciated, and who deserve the same attention and opportunity, like Howardena Pindell or Adrian Piper."

The Legacy of Lorna Simpson

Simpson's interrogation of race and gender issues with a minimal, sophisticated interplay between art and language has made her a much respected and influential figure within the realms of visual culture. American artist Glenn Ligon is a contemporary of Simpson's whose work similarly utilizes a visual relationship with text, which he calls 'intertextuality,' exploring how stencilled letters spelling out literary fragments, jokes or quotations relating to African-American culture can lead us to re-evaluate pre-conceived ideas from the past. Ligon was one of the founders of the term "Post-Blackness," formed with curator and writer Thelma Golden in the late 1990s, referring to a post-civil rights generation of African-American artists who wanted their art to not just be defined in terms of race alone. In the term Post-Black, they hoped to find "the liberating value in tossing off the immense burden of race-wide representation, the idea that everything they do must speak to or for or about the entire race."

The re-contextualization of historical inaccuracies in both Simpson and Ligon's practice is further echoed in the fearless, cut-out silhouettes of American artist Kara Walker, who walks headlong into some of the most challenging territory from American history. Arranging figures into theatrical narrative displays, she retells horrific stories from the colonial era with grossly exaggerated caricatures that force viewers into deeply uncomfortable territory.

In contrast, contemporary American artist Ellen Gallagher has tapped into the appropriation and repetition of Simpson's visual art, particularly her collages taken from African American magazine culture. Gallagher similarly lifts original source matter from vintage magazines including Ebony, Our World and Sepia, cutting apart and transforming found imagery with a range of unusual materials including plasticine and gold-leaf. Covering or masking areas of her figures' faces and hairstyles highlights the complexities of race in today's culture, which Gallagher deliberately teases out with materials relating to "mutability and shifting," emphasising the rich diversity of today's multicultural societies around the world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Boxcar Kids

Reading time: 10 minutes

A new gang of artists, armed with gall and heart and tools from Harbor Freight, threatens to diversify Provo, Utah, with fine art, artisan coffee, haircuts, tattoos, and community events. They’ve taken over the tired midcentury building located at 156 West 500 South and have turned it into a parlor of sorts, a source of golden light and autumnal galas and monthly Drink and Draws with nude models. They call the place The Boxcar Studios.

The Boxcar Studios opened twelve months ago, unofficially. Jake Buntjer—father, photographer, found art sculptor, and now community organizer—founded Boxcar when he acquired the building on a bargain lease. Inspired by Corey Fox, owner of Velour and godfather to Utah Valley’s music scene, Buntjer set out to create a marketplace and community for fine artists and their patrons. “I knew in my gut,” says Buntjer, “if I could acquire this space, if I could create the opportunity for myself and then share it with other people, that we could hook dreams. And if I hooked a dream with somebody and they hooked with me, then we could hook more dreams together and create an ecosystem that benefitted everybody.” Boxcar has since endured on Buntjer’s vision, enlisting artists’ faith and gumption and gristle from volunteers. On any given day at the Boxcar, Millennials and Gen-Xers can be found rewiring electrical circuitry, plumbing new pipes, nailing up reclaimed boards, or painting walls. On weekends you’ll find art shows, musical performances, mingles, and costume parties. This February you can attend a private carnival for $50, which includes live music by Timmy the Teeth, premium cocktails, fire dancers, contortionists, stilt walkers, and whatever shenanigans might ensue in such an environment. In recent months, Boxcar has hosted Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s gatherings, providing a free space for friends and community members to gather for drink and food.

Seven artist studios flank the rear of the Boxcar, while three shops comprise the storefront—Revolución Barbershop & Co., Man in the Moon Mercantile & Reclamation, and Rugged Grounds, a coffeehouse. Azure paint adorns the building’s face, corrugated steel roofing runs down its west side. Out front, on a crumbly sidewalk, a wooden sign beckons folks inside, where they are apt to meet Jeremiah “Pete” Hansen behind the glass counters of the Mercantile.

Pete is lean and blond, wears a newsboy cap. A reassuring Paul Newman-like smile springs easily and frequently across his face, erasing the worry that traces his temples and brow. Pete’s background is in the restaurant and construction industries and his first love is culinary arts, but the vagaries of life have sent him meandering. He got to know the Boxcar while patching its roof one day, working odd jobs. It didn’t take long for the unheated and leaky building—combined with Buntjer’s vision—to seduce Pete, like an empty frontier. He soon began regularly working and hanging around the Boxcar, volunteering his time. Now he mans the entry point five days a week.

What inspires a grown man to abandon a recurring paycheck for some impossible opportunity, to take a chance on art and community?

“The short story?” says Pete, “I grew up in a big-ass family, the seventh of nine kids. Always shared a room. Married young, always shared a house. Got divorced, didn’t know what the fuck. Got remarried, tried to make that work. Didn’t work out. I don’t know how to be alone. I don’t know who I am. I don’t know what 'me' is. So why not?” Besides, he adds, "I can reinvent myself, I can be whoever I want. And reality is what?”

Reality does seem to twist and morph inside the Boxcar. The Mercantile, for example, is bedecked with green soda bottles, burlap bags, clackety typewriters, trilobites, brass belt buckles, wired spectacles, fraying leather jackets, false teeth, and black-and-white postcards. Drunken Sailor Radio plays on Pandora. A gray housecat named Toby toes about, purrs. There’s a velour chaise lounge, a yellow Tonka truck, a stuffed piranha, bat, and boar’s head, one sheep skull covered in turquoise, and a brocade sofa in the colors of The Mystery Machine—sea green and aqua. In the evenings, bistro lighting colors the timbered room copper and gold. In the mornings, the large south-facing shop window is platinum white, a portal back to a world of concrete and cubicles, where the pathway is known. But inside the Boxcar, possibility wafts around like an invisible river, and there’s the sense that, if lucky, you can hitch and ride the flow.

Next door, inside Revolución Barbershop & Co., California natives E’Sau and Lizzy Negrete cut and buzz hair. Actually, Lizzy quietly works the counter, swiping cards, taking money, smiling at the conversations that ricochet around the shop. E’Sau wields the scissors, clipping hair with jabs and hooks, while she dances around each customer. Rectangular black-rimmed glasses accent her round face. She talks in loud, quick gestures, her tattooed arms unfurling in all directions. Old liquor bottles—Jack Daniels, Don Julio, Jim Beam—fitted with spray nozzles, line a shelf below a mirror. E’Sau’s been cutting hair for 24 years.

“I’m the oldest of fourteen kids,” she says, “and I have ten brothers. My mom bought me a pair of clippers from K-Mart one day, when I was 13. I’ve been cutting hair since.”

Being the eldest, E’Sau spent most of her life taking care of younger siblings. “I never got to know who I really am until I moved away,” she says. Until she came to Provo.

And until Revolución, she’s always barbered from home. Having an actual shop, for the Negretes, is a dream come true. To see it through, E’Sau provides the chutzpah, Lizzy provides pragmatic oversight, encouraging her rebellious partner to play by the rules and file for all the appropriate licenses.

To the other side of Mercantile lies Rugged Grounds, set to open for business this February. Partners Skyler Saenz and Sadie Crowley, with help from friends, have renovated the old tax and payroll office entirely with reclaimed materials, from the paneled walls to the stainless counters to the modified sawhorse tables. They plan to sell traditional espresso and coffee, but will also offer kombucha, pour-overs, and cold-brew. The two blow kisses to each other from across the room, hug when they collide in the kitchen area. They both are young and attractive, and their endearments give off an intoxicating air of youthful promise, but without naivety. What they have seems solid, rugged, adding charm to the already quaint quarters.

“I’ve thought about doing something like this forever,” says Sadie. “Since I was pre-teen. And Skylar thought about it forever, too.”

Skyler confirms this. “Big dream on a whim,” he says.

When Boxcar hosts a gathering, the three storefront shops come alive. Doorways connect the structural trio like tunnels between funhouse rooms. The Negrete’s Latino community descends on the brightly lit barbershop en force, showing this gringo what familial relationships should look like—the generous hugs and fearless laughter. Ceviche and tequila abound. In the dimly lit Rugged Grounds and Mercantile, the scent of dried fruits and cocoa drifts between the chatter of Provo’s curious and outcast, who flock to the Boxcar on such evenings. Espresso and soymilk swirl inside paper cups, mimicking déjà vu.

After coffee and conversation—or during or before, there are no rules—guests mingle their way up a flight of creaky stairs, northward through Buntjer’s own atelier, and back down a set of creaky stairs into the industrial tail of the Boxcar. Depending on the evening, a band plays on a makeshift stage or art hangs from the rafters—photographs, paintings, mixed-media installations. The artists in residence open their doors and answer questions about their work.

Painter and illustrator Chase Henson rents a studio. Pencils, brushes, and tubes of paint litter his space. A while back he was studying aviation mechanics, following his father’s footsteps, but an internship opened his eyes. Chase realized mechanics wasn’t for him, so he altered course and earned a degree in art. Around the same time he abandoned the religion of his upbringing, became fascinated with religion in general, and in particular Hinduism. He now portrays its mythologies and gods in his paintings, metamorphosed in various ways. Of the Boxcar he says, “This place saved my artistic life.” Chase recently lost a tattooing apprenticeship and was ready to forsake the starving artist’s way. Boxcar, with its burgeoning community and forthcoming tattoo shop, represents a second chance.

Artists desperately need second chances in Provo. With a pious religious base and a politically conservative worldview that spiders through its suburban sprawl, the third largest city in Utah feels more like the set of The Donna Reed Show than an actual metropolis. Culture is something primarily emitted via Mormondom. Artists who have succeeded in Provo tend to paint portraits of Jesus Christ or depict dead Mormon prophets, Mormon temples, scenes from the Book of Mormon, and so on. Photographers succeed by snapping happy and glistening pics of Utah’s scenery. So making Hindu-inspired paintings that connote mysticism (Chase Henson) or honest photos of naked men (Trevor Christensen) or found art sculptures that hint of death and magic (Jake Buntjer) or photos that color youth and playfulness with loneliness and nostalgia (Lyndi Bone) or mixed media that decry industrialism and corporatism (Kelly Larsen) is a labor of love and uphill battle. But the Boxcar has enabled this motley crew to concentrate their artistic efforts, and they are puncturing cultural barriers, pushing through.

The crew is more interested in building than in tearing down, however. Buntjer’s vision of Boxcar is inclusive. Despite being an ex-Mormon and divorcee—marks that Mormondom customarily frowns upon, even shames—Buntjer doesn’t want to alienate members of the dominant culture. He in fact sees Provo’s homogeneity as artistic promise—a clean page on which to score a new song. He wants to give back to the community that shaped him by sprouting a culture that it can one day appreciate. And if that day doesn’t come, well, he and the other misfits will have each other and whatever they make of themselves through art. “I just want the community,” Buntjer says. “I want church.”

The community is coming together, and maybe the “church” is too. Boxcar is akin to a clubhouse for adults, a chapel, a place of play and spiritual replenishing. Sometimes in the late hours, usually between one and four a.m., when the night is taut and black and all that remains of the crowds is echoing whispers, three or four or six overgrown youth will circle within the gold light, among the stuffed beasts and skeletal fragments and vintage tools, and share wine or whiskey or whatever alcohol can be found hiding in a dilapidated desk drawer. The stars turn overhead. Those gathered begin to skip and leapfrog their words, so that they end up communicating more through vibes and frequencies than actual language. Psychologists call this “flow,” except they’ve yet to study it in conversational contexts. To a stranger or latecomer, it would sound like gibberish. In truth, it’s a deeper form of communication than everyday chatter, something that occurs at the level of the soul, and often regards matters of the same—what it is or isn’t, how to attain it or express or channel it. The details of these revelries are often forgotten by morning, but lingering impressions remain—footprints on each being’s nucleus, pictographs of the night tattooed onto vital organs. Of these clubhouse sessions, Pete says, “They happen when they need to.” You can’t buy tickets. No money required.

The beasts and skeletons and tools belong to Buntjer. His studio is where the Boxcar’s more serious and subdued meetings occur. His also radiates the greatest amount of magic. Whereas the other studios feel like studios, splotched with paint, flung with framed illustrations and photos, Buntjer’s studio is part shop of horrors, part dreamland, part American Pickers collective. There are leather and felt hats, fur coats, and twenty-one pairs of rusty pliers. There are hammers, saws, tapes, an old tequila bottle filled with purple goop. Block letters on a beam read: MISTER PAUPER. There are springs, wires, cloths, razor blades, dressmaking torsos in wicker, iron, and plastic, and over twenty-five doll heads, many with their eyes plucked out. A horse bust sits blindfolded in one corner. There are canvas bags, model ships, birdhouses, dusty jewelry boxes, a wall of brass curiosities. Buntjer reimages the refuse when he sculpts, which involves grinding, cutting, stitching, tying, wiring, hammering, gluing, and dreaming. The floor creaks. Light streaks through its cracks. A stuffed desert bighorn sheep stands in the center of the room. Above it drapes a large white flag bearing a red X, as if to suggest: this is the place.

Buntjer, with his pointy beard and heeled boots, resembles a satyr. Fitting for a mythmaker. Between overseeing Boxcar’s operations, sculpting, shooting photos, pitching art shows, and directing art for a new theatre in Provo, Buntjer works sometimes eighteen hours in a day. He is in the Boxcar’s tail, the storefront, and out back unloading his Jeep all at once, planning, directing, organizing. Sculpting. Sometimes following a Boxcar event, which represents the climax of a month’s work, he retires to his studio, the hearth of Boxcar, on a burgundy sectional next to the desert bighorn, for a clubhouse session. For church. But even as he unwinds, a vision visibly turns in his head, one he has expressed a hundred times in a hundred different ways, but that always resounds the same:

“I knew in my gut if I could acquire this space, if I could create the opportunity for myself and then share it with other people, that we could hook dreams. And if I hooked a dream with somebody and they hooked with me, then we could hook more dreams together and create an ecosystem that benefitted everybody. Then maybe everybody could be a little more creative, a little more real, a little more daring, a little more risky, because they were connected to other people doing the same thing. It’s a family.”

A family of foolhardy misfits, a chest of coupled dreams. Without them, Boxcar is just an old building. But, for now, it feels like a train car being pulled toward some remarkable, enchanting place. And I, for one, am aboard, if only to see what's at the next stop.

A version of this story was originally published February, 2017, at Utah Stories.

0 notes