#like just Canada having it’s own distinct culture getting erased again

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Growing up I always thought Canada just used English spellings, but it wasn’t until moving to England that I learned Canada uses a combination of English and American spellings meaning it in fact has its own spellings

#don’t get me started on people in England accusing canada of spelling g everything American/wrong#and then vice versa#like just Canada having it’s own distinct culture getting erased again#Canada

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wendigo is Not What You Think

There’s been a recent flurry of discussion surrounding the Wendigo -- what it is, how it appears in fiction, and whether non-Native creators should even be using it in their stories. This post is dedicated to @halfbloodlycan, who brought the discourse to my attention.

Once you begin teasing apart the modern depictions of this controversial monster, an interesting pattern emerges -- namely, that what pop culture generally thinks of as the “wendigo” is a figure and aesthetic that has almost nothing in common with its Native American roots...but a whole lot in common with European Folklore.

What Is A Wendigo?

The Algonquian Peoples, a cluster of tribes indigenous to the region of the Great Lakes and Eastern Seaboard of Canada and the northern U.S., are the origin of Wendigo mythology. For them, the Wendigo (also "windigo" or "Witigo" and similar variations) is a malevolent spirit. It is connected to winter by way of cold, desolation, and selfishness. It is a spirit of destruction and environmental decay. It is pure evil, and the kind of thing that people in the culture don't like to talk about openly for fear of inviting its attention.

Individual people can turn into the Wendigo (or be possessed by one, depending on the flavor of the story), sometimes through dreams or curses but most commonly through engaging in cannibalism. Considering the long, harsh winters in the region, it makes sense that the cultural mythology would address the cannibalism taboo.

For some, the possession of the Wendigo spirit is a very real thing, not just a story told around the campfire. So-called "wendigo psychosis" has been described as a "culture-bound" mental illness where an individual is overcome with a desire to eat people and the certainty that he or she has been possessed by a Wendigo or is turning into a Wendigo. Obviously, it was white people encountering the phenomenon who thought to call it "psychosis," and there's some debate surrounding the whole concept from a psychological, historical, and anthropological standpoint which I won't get into here -- but the important point here is that the Algonquian people take this very seriously. (1) (2)

(If you're interested in this angle, you might want to read about the history of Zhauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow (or Jack Fiddler), a shaman who was known as something of a Wendigo hunter. I'd also recommend the novel Bone White by Ronald Malfi as a pretty good example of how these themes can be explored without being too culturally appropriative or disrespectful.)

Wendigo Depictions in Pop Culture

Show of hands: How many of you reading this right now first heard of the Wendigo in the Alvin Schwartz Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark book?

That certainly was my first encounter with the tale. It was one of my favorite stories in the book as a little kid. It tells about a rich man who goes hunting deep in the wilderness, where people rarely go. He finds a guide who desperately needs the money and agrees to go, but the guide is nervous throughout the night as the wind howls outside until he at last bursts outside and takes off running. His tracks can be found in the snow, farther and farther apart as though running at great speed before abruptly ending. The idea being that he was being dragged along by a wind-borne spirit that eventually picked him up and swept him away.

Schwartz references the story as a summer camp tale well-known in the Northeastern U.S., collected from a professor who heard it in the 1930s. He also credits Algernon Blackwood with writing a literary treatment of the tale -- and indeed, Blackwood's 1910 novella "The Wendigo" has been highly influential in the modern concept of the story.(3) His Wendigo would even go on to find a place in Cthulhu Mythos thanks to August Derleth.

Never mind, of course, that no part of Blackwood's story has anything in common with the traditional Wendigo myth. It seems pretty obvious to me that he likely heard reference of a Northern monster called a "windigo," made a mental association with "wind," and came up with the monster for his story.

And so would begin a long history of white people re-imagining the sacred (and deeply frightening) folklore of Native people into...well, something else.

Through the intervening decades, adaptations show up in multiple places. Stephen King's Pet Sematary uses it as a possible explanation for the dark magic of the cemetery's resurrectionist powers. A yeti-like version appears as a monster in Marvel Comics to serve as a villain against the Hulk. Versions show up in popular TV shows like Supernatural and Hannibal. There's even, inexplicably, a Christmas episode of Duck Tales featuring a watered-down Wendigo.

Where Did The Antlered Zombie-Deer-Man Come From?

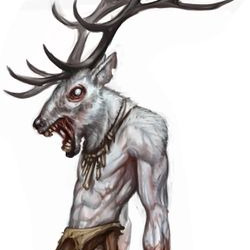

In its native mythology, the Wendigo is sometimes described as a giant with a heart of ice. It is sometimes skeletal and emaciated, and sometimes deformed. It may be missing its lips and toes (like frostbite). (4)

So why, when most contemporary (white) people think of Wendigo, is the first image that comes to mind something like this?

Well...perhaps we can thank a filmmaker named Larry Fessenden, who appears to be the first person to popularize an antlered Wendigo monster. (5) His 2001 film (titled, creatively enough, Wendigo) very briefly features a sort of skeletal deer-monster. He’d re-visit the design concept in his 2006 film, The Last Winter. Reportedly, Fessenden was inspired by a story he’d heard in his childhood involving deer-monsters in the frozen north, which he connected in his mind to the Algernon Blackwood story.

A very similar design would show up in the tabletop game Pathfinder, where the “zombie deer-man” aesthetic was fully developed and would go on to spawn all sorts of fan-art and imitation. (6) The Pathfinder variant does draw on actual Wendigo mythology -- tying it back to themes of privation, greed, and cannibalism -- but the design itself is completely removed from Native folklore.

Interestingly, there are creatures in Native folklore that take the shape of deer-people -- the ijiraq or tariaksuq, shape-shifting spirits that sometimes take on the shape of caribou and sometimes appear in Inuit art in the form of man-caribou hybrids (7). Frustratingly, the ijiraq are also part of Pathfinder, which can make it a bit hard to find authentic representations vs pop culture reimaginings. But it’s very possible that someone hearing vague stories of northern Native American tribes encountering evil deer-spirits could get attached to the Wendigo, despite the tribes in question being culturally distinct and living on opposite sides of the continent.

That “wendigo” is such an easy word to say in English probably has a whole lot to do with why it gets appropriated so much, and why so many unrelated things get smashed in with it.

I Love the Aesthetic But Don’t Want to Be Disrespectful, What Do I Do?

Plundering folklore for creature design is a tried-and-true part of how art develops, and mythology has been re-interpreted and adapted countless times into new stories -- that’s how the whole mythology thing works.

But when it comes to Native American mythology, it’s a good idea to apply a light touch. As I’ve talked about before, Native representation in modern media is severely lacking. Modern Native people are the survivors of centuries of literal and cultural genocide, and a good chunk of their heritage, language, and stories have been lost to history because white people forcibly indoctrinated Native children into assimilating. So when those stories get taken, poorly adapted, and sent back out into the public consciousness as make-believe movie monsters, it really is an act of erasure and violence, no matter the intentions of the person doing it. (8)

So, like...maybe don’t do that?

I won’t say that non-Native people can’t be interested in Wendigo stories or tell stories inspired by the myth. But if you’re going to do it, either do it respectfully and with a great deal of research to get it accurate...or use the inspiration to tell a different type of story that doesn’t directly appropriate or over-write the mythology (see above: my recommendation for Bone White).

But if your real interest is in the “wendigocore” aesthetic -- an ancient and powerful forest protector, malevolent but fiercely protective of nature, imagery of deer and death and decay -- I have some good news: None of those things are really tied uniquely to Native American mythology, nor do they have anything in common with the real Wendigo.

Where they do have a longstanding mythic framework? Europe.

Europeans have had a long-standing fascination with deer, goats, and horned/antlered forest figures. Mythology of white stags and wild hunts, deer as fairy cattle, Pan, Baphomet, Cernunnos, Herne the Hunter, Black Phillip and depictions of Satan -- the imagery shows up again and again throughout Greek, Roman, and British myth. (9)

Of course, some of these images and figures are themselves the product of cultural appropriation, ancient religions and deities stolen, plundered, demonized and erased by Christian influences. But their collective existence has been a part of “white” culture for centuries, and is probably a big part of the reason why the idea of a mysterious antlered forest-god has stuck so swiftly and firmly in our minds, going so far as to latch on to a very different myth. (Something similar has happened to modern Jersey Devil design interpretations. Deer skulls with their tangle of magnificent antlers are just too striking of a visual to resist).

Seriously. There are so, so many deer-related myths throughout the world’s history -- if aesthetic is what you’re after, why limit yourself to an (inaccurate) Wendigo interpretation? (10)

So here’s my action plan for you, fellow white person:

Stop referring to anything with antlers as a Wendigo, especially when it’s very clearly meant to be its own thing (the Beast in Over the Garden Wall, Ainsworth in Magus Bride)

Stop “reimagining” the mythology of people whose culture has already been targeted by a systematic erasure and genocide

Come up with a new, easy-to-say, awesome name for “rotting deer man, spirit of the forest” and develop a mythology for it that doesn’t center on cannibalism

We can handle that, right?

This deep dive is supported by Ko-Fi donations. If you’d like to see more content, please drop a tip in my tip jar. Ko-fi.com/A57355UN

NOTES:

1 - https://io9.gizmodo.com/wendigo-psychosis-the-probably-fake-disease-that-turns-5946814

2 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wendigo#Wendigo_psychosis

3 - https://www.gutenberg.org/files/10897/10897-h/10897-h.htm

4 - https://www.legendsofamerica.com/mn-wendigo/

5- https://www.reddit.com/r/Cryptozoology/comments/8wu2nq/wendigo_brief_history_of_the_modern_antlers_and/

6 - https://pathfinderwiki.com/wiki/Wendigo

7 - https://www.mythicalcreaturescatalogue.com/single-post/2017/12/06/Ijiraq

8 - https://www.backstoryradio.org/blog/the-mythology-and-misrepresentation-of-the-windigo/

9 - https://www.terriwindling.com/blog/2014/12/the-folklore-of-goats.html

10 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deer_in_mythology

#horror#folklore#mythology#deep dive#wendigo#cultural appropriation#monster design#creature design#long post#if you need a place to channel your deerman aesthetic#may I suggest huntokar from welcome to nightvale#100% fictional#100% awesome

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

R&R: Race-based Reminders

by @naruhearts || Jan 24 2018

- - - -

Today is a good day to lay down some key points:

1. White/white-identifying individuals must realize that they CANNOT speak for all POC, including their own POC friends. POC may be intersectionally and systematically oppressed and ostracized as a collective in white-constructed Western society, but differing ethnic minority groups possess differing experiences. It is racially inappropriate for white people to tell certain POC what is or isn’t offensive, since each varied POC experience is not painted with broad strokes; they aren’t the same.

What a white individual may perceive as offensive/non-offensive does NOT hold the same meanings and connotations for a POC.

2. Just because something is ‘fact’ doesn’t discount how POC interpret it and consume it. White people might correct POC who point out something in a TV show, take offense to it, and thus discuss it or make jokes about it. White viewers might be argumentative with POC viewers and claim that: “the characters aren’t racist! I’m pointing out the facts! Nothing indicates they’re racist and there’s no substantial basis for your accusations! The writers didn’t mean for it to be racist!”

“The writers didn’t mean for it to be racist” —> tries to push subconscious white supremacy under the rug, exempt white people from race-based responsibility and accountability, and make the POC reality invisible; I will talk about this more in the future, but white writers do not have to have CONSCIOUS AUTHORIAL INTENT in order to write something that is interpreted as potentially racist. White-painted historical narratives influence a white person’s behaviour and by socialized design, they can incorporate racism into ANYTHING they do, subconscious or not (due to internalization of white dominance).

Don’t be defensive. Media consumption by white people is entirely DISTINCT from media consumption by People of Colour.

Again, a white person CANNOT establish an objective view for POC, especially when it comes to societal mediums like media. If they think that TV show characters can be racist or if they think something in the literary narrative(s) potentially comes across as racist, they are 100% entitled to this belief (this is elaborated upon in later points). Refrain from overall defensiveness and LISTEN to POC. After all, POC are oppressed; white people are not.

***Please do NOT tell POC that they are “fake woke” if you aren’t POC yourself, even if you personally disagree with anything they said or did. This is a form of racial bullying.

3. Other POC groups lack the authority to exercise the N-word if they do not belong to the Black community. The N-word exists within the Black sociocultural context and is attached to historically unjust/oppressive narratives, policy development, and legal/institutional action against Black POC. It isn’t the business of other POC groups to contribute opinions about a Black person’s racism jokes or how they choose to perceive racism, just like it isn’t a Black POC’s business to contribute adjacent opinions about racism jokes or perceptions of racism of Chinese POC, Filipino POC etc.

***As a Filipina POC, I will never, for example, disclose or enforce an opinion about c***k jokes being thrown around by Chinese POC. Their respective racial space stays untouched.

4. The dimension of colourism —> very real. Light-skinned privilege is pervasive and underpins white privilege within the sociocultural Western context, where light-skinned individuals are either considered “not POC enough” or “not white enough”. If a dark-skinned POC states that other light-skinned POC are “not POC enough”, it is NOT a white person’s business to defend their light-skinned POC friend(s) without allowing or inviting those friends to speak (this is addressed in the following point).

5. A white person is entitled to their opinion - and yes, they are certainly entitled to defend their POC friend(s) - but their opinion ultimately does NOT matter nor does it hold importance because the racial discussion occurring between POCs excludes them in the first place. White people cannot relate (nor do they belong) within the underprivileged racial context in that POC lack systemic and institutional power/influence when it comes to their opinions, henceforth it’s NOT a priority for the white person’s opinion to be heard; it is more racially appropriate for white people to withhold such opinions and instead let the debate between POCs continue uninterrupted. People of Colour experience enough interruption and talking over by the predominantly White sphere of North American society.

The following excerpt from USA TODAY OPINION is highly applicable to whiteness and race-based discourse:

“Most people think of the Ku Klux Klan when they hear “white supremacy.” But the term just means that whiteness is the supreme value, which in the news media it is. As feminist writer Anushay Hossain noted to me, “Just the fact that Megyn Kelly feels she can have a conversation about race on television with three white people is the definition of white privilege.” Before anything offensive was said, there was already a problem” (Powers, 2018)

6. Do not put in argumentative or defensive interjections if POC/BIPOC (Black/Indigenous POC) attempt to address your racist actions, especially ones that are “invisible” to you and thus “can’t be racist behaviour” (aka white fragility). Trust the word(s) of POC/BIPOC people. We witness racism everyday as ethnic minority-labelled groups and can hence distinguish underlying racist patterns easily, from the obvious to the nuanced. We think of ourselves in racial terms and are able to describe how our lives are shaped by our race within, again, Whiteness-governed society; white people cannot do these things (fail to think of themselves in racial terms as a larger group; fail to describe how their own lives are shaped by their race) since they hold the (unearned) privilege to walk through life unaffected by social, cultural, and political systems that A. benefit white people, and B. disadvantage People of Colour (aka white privilege).

7. Another point: do not tokenize your POC friends. Saying that you cannot be racist “because you have POC friends” reduces your POC friends to nothing but caricatures who elevate your social status and erase your accountability and complicity. Racism does not manifest ONLY through obvious external attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours, but through internal attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours. Racism exists via subconscious systemic forces (i.e. social media) that permeate society in numerous ways.

In other words, racism is a multifaceted subconscious/conscious structure, “not an event” (DiAngelo, 2018).

8. Some common white myths: “a. I don’t see colour” b. “Focusing on race divides us” c. “It’s about class, not race” —> Firstly, saying one doesn’t see colour perpetuates erasure of the POC experience/reality. Secondly, race already divides us. Thirdly, we CANNOT talk about other systemic forces like socioeconomic class without addressing race. Race is inherently interweaved into other structural dimensions. It’s why BIPOC/POC are paid less than white employees/unequally treated in terms of job capability, struggle to find jobs, are unable to afford three-story suburban houses, and can never seem to find favour no matter how hard we work.

Here we go into the issue of legal structures —> Black people in the U.S., for example, were historically barred from purchasing land, investing their money, and seeking permanent lodging. In 1960s Canada, Indigenous POC were plucked from their homes, abused in residential schools, lost their land, and could not gain Canadian rights and citizenship unless they renounced their Aboriginal identity; the Canadian Chinese Immigrant Act of 1885 implemented the Chinese Head Tax to discourage Chinese POC from entering Canada after the Canadian Pacific Railway was created. Overall, POC were confined to financial poverty/kept from flourishing financially. Filipino immigrants in Canada, for example, tend to move into low-wage backdoor jobs involving the transfer of labour from white people to POC people e.g. nannies, factory workers, and foodservice (these include my Filipino relatives in these jobs), while white individuals tend to take up jobs of higher public status e.g. delegation, policy-making (Gibb & Wittman, 2012). In a predominantly white-privileged society, the BIPOC/POC financial reality lags.

***It’s not about “working hard to get to the top” — it’s about “working hard to eliminate racism that hinders us from getting to the top and staying there.” We will always be five steps behind white people today (who, underneath an individualistic ideology, think financial merit can be earned if one works hard enough regardless of race —> again this perpetuates the erasure of POC realities and ignores the POC financial hardship experience + systemic racist forces at play. We do not live in a meritocracy, but in a racial hierarchy). Historical racism is the reason for it.

9. Finally: appropriate language.

Refrain from using derogatory racial terms such as “coloured” and corresponding rhetoric when referring to People of Colour.

If you intend to be a non-BIPOC/non-POC ally, please expand your horizons on appropriate race-based term usage when engaging in racial discourse. Continuous education with POC is key!

#fandom racism#spn + racism#spn + white fragility#white fragility#white privilege#racism#-mod naruhearts#fandomcolourofmyskin#fcs#long post for ts#white narratives#white history#racism in fandom

25 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Stacey McKenna

29 January 2019

I read the highway signs aloud as I whizzed past, trying to mimic the sing-songy Québécois twang on the radio. It was early May, and I chattered to myself in French as I cut north out of Québec City, through Jacques-Cartier National Park, passing signs warning against collisions with moose and signalling turnoffs to lakes still cloaked in patchworks of ice. I was headed towards the shores and clifftops of one of the world’s longest fjords, hoping to glimpse whales, ride horses and practice a language that I’ve spoken for most of my life, but never quite embraced as my own.

French wasn’t something I chose for myself. The daughter of a Francophile father, I learned it through the Martine storybooks my dad read to me at bedtime, a toddlerhood spent in Strasbourg and endless dad-mandated classes at summer camps and schools in the US, where I grew up. My dad has loved France since he was young. He’s spent years in the country since his first stay as a high-school exchange student, and when I ask him what he loves about the place, he waxes on about friendships and food, beautiful cities and a particular joie de vivre. I now understand that he always wanted to share that with me.

View image of Writer Stacey McKenna travelled to Québec in hopes of practicing the French language (Credit: Credit: Ken Gillespie Photography/Alamy)

My parents tell me that when I was two or three years old, I did have my own relationship with the language: I refused to speak it with them, yet happily babbled on with my babysitter in Strasbourg. But most of the French interactions I recall from my childhood happened in Paris during my self-conscious adolescence. I would tag along with my dad during holidays, bored by the same long meals and adult conversations he so enjoyed. And when I tried setting out on my own, even my most basic attempts to buy a croissant and talk to people were marked by brusque corrections of my American accent.

You may also be interested in: • The true ‘granddaddy’ of the Alps • The island of 1,000 shipwrecks • What it means to know when to leave

I kept returning to France with my dad well into adulthood, but I did so reluctantly, no longer wanting to talk for myself or explore on my own. I had lost confidence in my ability to get the language right, so I let go of my desire to speak it.

That is until the first time I visited Québec 14 years ago as a graduate student. My decision to study in Montréal had less to do with French itself than with my romantic notion of life in a bilingual city where I could, in theory, speak English too.

A relic of pre-revolutionary France, Canadian French retains old qualities that make it difficult for the uninitiated to grasp. “We use words [the French] don’t use anymore, and make distinctions between sounds they’ve flattened,” explained Emilie Nicolas, a Québec-born linguistic anthropology graduate student at the University of Toronto.

Although my classes were in English, I lived in a French neighbourhood and was met with patience and smiles as I struggled with the mellifluous accent and unfamiliar local words. Something about the Québécois diphthongs and nasally vowels lured me in. My interest in French was piqued – even if my painful linguistic past caused my confidence to remain low.

View image of McKenna’s father, a Francophile, had taught her French as a child, when they temporarily lived in Strasbourg (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

Québec’s own fraught linguistic history dates back to 1763, when France ceded the area to Britain. For the next 200 years, the local government filtered French out of schools and adopted measures that benefitted English speakers. By the 1960s, francophones remained worse off economically and socially than their anglophone counterparts, and a distinct cultural and class divide permeated the province.

The 1970s brought a push for pro-French language planning, and with it bills – like the Charter of the French Language – that explicitly linked French to Québécois identity and made it the only official language of the province. But, for some, the fear that French will once again come under attack lingers. That tension was palpable for me in the nine months I lived in Montréal. I never knew which language I was supposed to speak in a given situation, and each choice felt rife with culturally charged meaning that piled on my pre-existing anxiety.

So when I returned last spring, the irony wasn’t lost on me. Here I was, searching for personal peace with French in a region where the language has been mired in discord for centuries. But this time, rather than staying in Montréal, I headed deeper into the province and forced myself to plough through my timidity in a place where most people are monolingual.

View image of Although McKenna continued to travel to France with her father, she lost the desire to speak the language (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

As I stepped up to the car rental counter at Québec City’s Jean Lesage International Airport, I rehearsed my lines with the trepidation that comes from an upbringing of terse correction: "Je m'appelle Stacey McKenna. J'ai réservé une voiture." I forced the words through the lump of nerves in my throat. The woman behind the counter beamed and began rattling off details – all in French. By the time I settled into my little red Volkswagen and set out on the road, I felt ready.

As I traced a loop from Québec City to the Saguenay Fjord and through the region of Charlevoix, French started to feel like a key to the region’s secrets. I arrived in the little town of L’Anse-Saint-Jean just ahead of sea kayaking and whale watching season, so in the morning over breakfast, I asked my bilingual host (guiltily, in English) for advice. He suggested a nearby hike, then asked whether I spoke any French. “I do,” I replied, staring at my plate and pushing my egg around with my fork. “But not nearly as well as you speak English."

“Don’t be shy,” he said. “We like hearing your English accent.”

I felt my belly warm with a newfound affection for the tiny but significant experiences that French – even my imperfect French – might unlock here

According to Richard Bourhis, linguistic psychologist at Université du Québec à Montréal, schooling on pronunciation tends to be less rigid in Québec than in France, which likely creates a difference in how foreign speakers are perceived. “[In France] they're taught that they can’t make mistakes in French, so they don't want you to make a mistake,” he said. “Francophones all over Canada don't mind using English or French with all kinds of accents… so long as we can understand each other.”

As my host had warned, the trail was still slick with snowmelt. I followed it upward – scanning the forest for signs of moose as I went – and soon found myself tromping through lingering drifts.

I turned back before the snow got too deep to cross in trainers, and on my descent, I ran into a group dressed far more appropriately for the muddy spring terrain than I. They asked me in French if there was still snow on top, and to my surprise, I didn’t hesitate. “Je ne sais pas. Je ne suis pas allée au sommet.” (“I don’t know. I didn’t go to the summit.”) They smiled, thanked me and continued their ascent. I felt my belly warm with a newfound affection for the tiny but significant experiences that French – even my imperfect French – might unlock here.

View image of Rather than staying in the bilingual city of Montréal, McKenna travelled deeper into Québec where most people are monolingual (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

The next day, I headed to Baie-Sainte-Catherine, where I caught a whale-watching boat through the Saguenay-St Lawrence Marine Park. Bracing against the wind and the rocking waves, I squinted, hoping to spot the tell-tale spray from a blowhole. As I listened to the on-board scientist talking easily in French and English about the underwater ecosystems, I wondered whether, by resisting for all these years, I’d squandered my own chance at bilingualism.

It’s a mistake French-Canadians seem less likely to make, as Québec’s French-speaking population is currently driving an increase in Canada’s bilingualism rate. “We’re very francophone still, but we don’t see speaking multiple languages as an either/or thing,” Nicolas said. “It adds. It doesn’t erase or threaten who you are in the same way it once did.”

This attitude was evident all over the province: at the Musée du Fjord in Saguenay; the cafe in Baie-Saint-Paul; the restaurant in Québec City. Over and over again, people encouraged me with their patience, asked where I had learned French and complimented my efforts. Inspired by the chance to practice this familiar language in a new, friendlier setting, I suddenly found myself overwhelmed by the pleasure of speaking French. I started drawing out conversations and asking for directions and recommendations I didn’t need. French had lost its tarnish. But more than that, it was becoming mine.

View image of Stacey McKenna: “I suddenly found myself overwhelmed by the pleasure of speaking French” (Credit: Credit: Pierre Rochon photography/Alamy)

When I returned to Québec City, I walked cobbled streets below matte metal roofs. The sky was grey, and I was reminded of days dawdling around Paris with my father. Grateful for the years he had insisted I learn his favourite language, I pulled out my phone and texted: "Je suis à Québec. C'est bon, mais ça serait mieux si tu étais ici." (“I’m in Québec. It's good, but it would be better if you were here.”) He agreed, and suggested we visit Québec together one day.

French had lost its tarnish – but more than that, it was becoming mine

After five days on the mostly francophone roads of rural Québec, I hopped a train to Montréal, home to the majority of the province’s bilingual residents and much of its linguistic tension. Six months prior, provincial legislators had unanimously approved a motion banning the city’s ubiquitous ‘bonjour-hi’ greeting. For nationalists, the phrase is a symbolic threat against French. But according to Bourhis, it’s an embrace of bilingualism, and a way to welcome people of either mother tongue. And despite the resolution, it isn’t going anywhere.

I dropped my bags at my hotel and headed to a glass-fronted restaurant near Old Montréal for lunch. As I took my seat, the server offered a cheery “Bonjour, hi!”. I returned the greeting, and in French free from fear, asked to see a menu.

Travel Journeys is a BBC Travel series exploring travellers’ inner journeys of transformation and growth as they experience the world.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

BBC Travel – Adventure Experience

0 notes

Link

By Stacey McKenna

29 January 2019

I read the highway signs aloud as I whizzed past, trying to mimic the sing-songy Québécois twang on the radio. It was early May, and I chattered to myself in French as I cut north out of Québec City, through Jacques-Cartier National Park, passing signs warning against collisions with moose and signalling turnoffs to lakes still cloaked in patchworks of ice. I was headed towards the shores and clifftops of one of the world’s longest fjords, hoping to glimpse whales, ride horses and practice a language that I’ve spoken for most of my life, but never quite embraced as my own.

French wasn’t something I chose for myself. The daughter of a Francophile father, I learned it through the Martine storybooks my dad read to me at bedtime, a toddlerhood spent in Strasbourg and endless dad-mandated classes at summer camps and schools in the US, where I grew up. My dad has loved France since he was young. He’s spent years in the country since his first stay as a high-school exchange student, and when I ask him what he loves about the place, he waxes on about friendships and food, beautiful cities and a particular joie de vivre. I now understand that he always wanted to share that with me.

View image of Writer Stacey McKenna travelled to Québec in hopes of practicing the French language (Credit: Credit: Ken Gillespie Photography/Alamy)

My parents tell me that when I was two or three years old, I did have my own relationship with the language: I refused to speak it with them, yet happily babbled on with my babysitter in Strasbourg. But most of the French interactions I recall from my childhood happened in Paris during my self-conscious adolescence. I would tag along with my dad during holidays, bored by the same long meals and adult conversations he so enjoyed. And when I tried setting out on my own, even my most basic attempts to buy a croissant and talk to people were marked by brusque corrections of my American accent.

You may also be interested in: • The true ‘granddaddy’ of the Alps • The island of 1,000 shipwrecks • What it means to know when to leave

I kept returning to France with my dad well into adulthood, but I did so reluctantly, no longer wanting to talk for myself or explore on my own. I had lost confidence in my ability to get the language right, so I let go of my desire to speak it.

That is until the first time I visited Québec 14 years ago as a graduate student. My decision to study in Montréal had less to do with French itself than with my romantic notion of life in a bilingual city where I could, in theory, speak English too.

A relic of pre-revolutionary France, Canadian French retains old qualities that make it difficult for the uninitiated to grasp. “We use words [the French] don’t use anymore, and make distinctions between sounds they’ve flattened,” explained Emilie Nicolas, a Québec-born linguistic anthropology graduate student at the University of Toronto.

Although my classes were in English, I lived in a French neighbourhood and was met with patience and smiles as I struggled with the mellifluous accent and unfamiliar local words. Something about the Québécois diphthongs and nasally vowels lured me in. My interest in French was piqued – even if my painful linguistic past caused my confidence to remain low.

View image of McKenna’s father, a Francophile, had taught her French as a child, when they temporarily lived in Strasbourg (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

Québec’s own fraught linguistic history dates back to 1763, when France ceded the area to Britain. For the next 200 years, the local government filtered French out of schools and adopted measures that benefitted English speakers. By the 1960s, francophones remained worse off economically and socially than their anglophone counterparts, and a distinct cultural and class divide permeated the province.

The 1970s brought a push for pro-French language planning, and with it bills – like the Charter of the French Language – that explicitly linked French to Québécois identity and made it the only official language of the province. But, for some, the fear that French will once again come under attack lingers. That tension was palpable for me in the nine months I lived in Montréal. I never knew which language I was supposed to speak in a given situation, and each choice felt rife with culturally charged meaning that piled on my pre-existing anxiety.

So when I returned last spring, the irony wasn’t lost on me. Here I was, searching for personal peace with French in a region where the language has been mired in discord for centuries. But this time, rather than staying in Montréal, I headed deeper into the province and forced myself to plough through my timidity in a place where most people are monolingual.

View image of Although McKenna continued to travel to France with her father, she lost the desire to speak the language (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

As I stepped up to the car rental counter at Québec City’s Jean Lesage International Airport, I rehearsed my lines with the trepidation that comes from an upbringing of terse correction: "Je m'appelle Stacey McKenna. J'ai réservé une voiture." I forced the words through the lump of nerves in my throat. The woman behind the counter beamed and began rattling off details – all in French. By the time I settled into my little red Volkswagen and set out on the road, I felt ready.

As I traced a loop from Québec City to the Saguenay Fjord and through the region of Charlevoix, French started to feel like a key to the region’s secrets. I arrived in the little town of L’Anse-Saint-Jean just ahead of sea kayaking and whale watching season, so in the morning over breakfast, I asked my bilingual host (guiltily, in English) for advice. He suggested a nearby hike, then asked whether I spoke any French. “I do,” I replied, staring at my plate and pushing my egg around with my fork. “But not nearly as well as you speak English."

“Don’t be shy,” he said. “We like hearing your English accent.”

I felt my belly warm with a newfound affection for the tiny but significant experiences that French – even my imperfect French – might unlock here

According to Richard Bourhis, linguistic psychologist at Université du Québec à Montréal, schooling on pronunciation tends to be less rigid in Québec than in France, which likely creates a difference in how foreign speakers are perceived. “[In France] they're taught that they can’t make mistakes in French, so they don't want you to make a mistake,” he said. “Francophones all over Canada don't mind using English or French with all kinds of accents… so long as we can understand each other.”

As my host had warned, the trail was still slick with snowmelt. I followed it upward – scanning the forest for signs of moose as I went – and soon found myself tromping through lingering drifts.

I turned back before the snow got too deep to cross in trainers, and on my descent, I ran into a group dressed far more appropriately for the muddy spring terrain than I. They asked me in French if there was still snow on top, and to my surprise, I didn’t hesitate. “Je ne sais pas. Je ne suis pas allée au sommet.” (“I don’t know. I didn’t go to the summit.”) They smiled, thanked me and continued their ascent. I felt my belly warm with a newfound affection for the tiny but significant experiences that French – even my imperfect French – might unlock here.

View image of Rather than staying in the bilingual city of Montréal, McKenna travelled deeper into Québec where most people are monolingual (Credit: Credit: Stacey McKenna)

The next day, I headed to Baie-Sainte-Catherine, where I caught a whale-watching boat through the Saguenay-St Lawrence Marine Park. Bracing against the wind and the rocking waves, I squinted, hoping to spot the tell-tale spray from a blowhole. As I listened to the on-board scientist talking easily in French and English about the underwater ecosystems, I wondered whether, by resisting for all these years, I’d squandered my own chance at bilingualism.

It’s a mistake French-Canadians seem less likely to make, as Québec’s French-speaking population is currently driving an increase in Canada’s bilingualism rate. “We’re very francophone still, but we don’t see speaking multiple languages as an either/or thing,” Nicolas said. “It adds. It doesn’t erase or threaten who you are in the same way it once did.”

This attitude was evident all over the province: at the Musée du Fjord in Saguenay; the cafe in Baie-Saint-Paul; the restaurant in Québec City. Over and over again, people encouraged me with their patience, asked where I had learned French and complimented my efforts. Inspired by the chance to practice this familiar language in a new, friendlier setting, I suddenly found myself overwhelmed by the pleasure of speaking French. I started drawing out conversations and asking for directions and recommendations I didn’t need. French had lost its tarnish. But more than that, it was becoming mine.

View image of Stacey McKenna: “I suddenly found myself overwhelmed by the pleasure of speaking French” (Credit: Credit: Pierre Rochon photography/Alamy)

When I returned to Québec City, I walked cobbled streets below matte metal roofs. The sky was grey, and I was reminded of days dawdling around Paris with my father. Grateful for the years he had insisted I learn his favourite language, I pulled out my phone and texted: "Je suis à Québec. C'est bon, mais ça serait mieux si tu étais ici." (“I’m in Québec. It's good, but it would be better if you were here.”) He agreed, and suggested we visit Québec together one day.

French had lost its tarnish – but more than that, it was becoming mine

After five days on the mostly francophone roads of rural Québec, I hopped a train to Montréal, home to the majority of the province’s bilingual residents and much of its linguistic tension. Six months prior, provincial legislators had unanimously approved a motion banning the city’s ubiquitous ‘bonjour-hi’ greeting. For nationalists, the phrase is a symbolic threat against French. But according to Bourhis, it’s an embrace of bilingualism, and a way to welcome people of either mother tongue. And despite the resolution, it isn’t going anywhere.

I dropped my bags at my hotel and headed to a glass-fronted restaurant near Old Montréal for lunch. As I took my seat, the server offered a cheery “Bonjour, hi!”. I returned the greeting, and in French free from fear, asked to see a menu.

Travel Journeys is a BBC Travel series exploring travellers’ inner journeys of transformation and growth as they experience the world.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

BBC Travel – Adventure Experience

0 notes