#like it portrays the idea that its unfathomable for him to go anywhere on his own and so in that vein . Interesting Storytelling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

everyday i constantly think of masato's wheelchair and if that's his only one/main one no wonder he's so pissed at everyone

#snap chats#someone pointed this out to me like last year so im stealing it sorry cause I Think Of It Constantly#the handling of masato's disability will forever annoy me esp with how vague it is but esp his chair#one day ill draw masato with an appropriate wheelchair. maybe then he'll be happy for once#in a way i guess it could tie into how restricted or trapped he felt since the type of chair he's shown is more like. a hospital one#and not one youd really use as a regular user- like in that vein it is a bit of storytelling in that he can ONLY go out with help#since hospital chairs are SO much different from home chairs ESPECIALLY in regards to mobility and independence the user has#AND NOT TO MENTION HOW UNCOMFORTABLE THOSE CHAIRS ARE get his ass a proper cushion P L E A S E#like it portrays the idea that its unfathomable for him to go anywhere on his own and so in that vein . Interesting Storytelling#theres a lot of implications going on here if im so honest and again it makes for Really Interesting Story Telling#however i refuse to give rgg credit like that when it comes to disabilities. ... they havent earned that from me yet#see this is why the vagueness of his condition annoys me because he's shown to be independent enough to roll himself to his elevator#and presumably get himself dressed but he cant have a proper chair ?#because ik there are people who have expressed they have conditions where even writing is tiring#so if his condition was in-line with that and it was hard for him to push himself in his chair then i could buy it#obviously the issue lies with his lungs but i just want to know the full extent yk...#to wrap this up tho ive been thinking of character design in rgg and how we dont give credit to it enough#sooooo if i make a second post ten minutes from now thats why cause i keep forgetting to spam my thoughts on here LMAO#ok bye

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6 – So Long, and Thanks For All the Fish [TST 1/2]

The chapter title comes from the wonderful Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy book series – drop this meta and read them immediately.

No, no he [Moriarty] would never be that disappointing. He’s planned something, something long-term. Something that would take effect if he never made it off that rooftop alive. Posthumous revenge – no, better than that. Posthumous game.

This is what Sherlock says about Moriarty in the very first scene of TST, and on rewatch the application to Mofftiss is startling. Trust the writers – a short-term disappointment for a long-term excitement, if you will. The reference to the rooftop is a way of pointing out just how far back this has been planned – in other words, the seeming randomness of the series is not in fact random. But let’s see how that plays out in TST.

This episode opens, as so many have pointed out, with doctored footage, as though deliberately showing us how stories can be rewritten. However, we only get glimpses of the footage at the start of the episode – the extensive old footage is not security camera footage, but recap footage from s3, and specifically the end of HLV. The idea that there is something classified, hidden, that we don’t have the full story, is meant to be associated with the actual show Sherlock, not just the camera footage – it would have been very easy to give us most of the same footage in security camera style, but they deliberately reused shots from the show to make us doubt their own authenticity. So far, so good.

The first thing that I (and most of my friends) noticed about this scene, however, is that it’s not good. The writing is questionable, to say the least. The serious resolution to the problem of Magnussen’s murder is interrupted by Sherlock tweeting, brotherly bickering, hyperactive and possibly high Sherlock being played for comedy (complete with mock opera). And then, perhaps the worst lines of the show so far:

SHERLOCK: I always know when the game is on. Do you know why?

SMALLWOOD: Why?

SHERLOCK: Because I love it.

Like a lot of this show, think about those lines for more than a nanosecond and they really don’t make sense. You’ve got to think about them for a lot longer before they start to again. This, I think, is where BBC Sherlock’s self-parody really starts. TAB focuses on parodying, critiquing and rewriting historical adaptations, but it’s easy to see the merging of all of the undeniably Sherlock elements into one parodically awful scene. The quick quips that are supposed to be clever and that are so common in Moffat’s dialogue are seen in that moment of dialogue – but the quip isn’t clever anymore, it’s empty. The same catchphrase of ‘the game is on’ comes back, and the quintessential use of technology is referenced in Sherlock’s Twitter account, where again his #OhWhatABeautifulMorning is unfathomably glib. Our Sherlock is also better known than previous adaptations for his drug abuse, and this also gets referenced, but here it gets played for comedy, which is incongruous with the rest of the show – in fact, THoB, HLV and TAB all take it pretty seriously, so to see it played off as a joke is tonally questionable. In other words, here we have Sherlock caricatured as a programme, in one scene – and it’s horrible.

(We should also notice that the use of Twitter is important – it underlies a lot of the glib comedy in this episode, with Sherlock later Tweeting #221BringIt (which is so unbelievably queer?). In Sherlock, Moffat use Twitter rather than Tumblr to comment on fan reaction to Sherlock, probably because their older audience will have no idea what Tumblr is, but also because Twitter is much more mainstream in its appreciation. Twitter takes centre stage in TEH, with #SherlockLives and the scene with the support group. The joke there is about the sheer level of how-did-he-do-it mania that gripped the public – so when we see Twitter again, we should be thinking about an extratextual as well as a textual response to Sherlock, and how Sherlock’s behaviour on Twitter in this episode might caricature the way that he is seen from the outside.)

I don’t truly buy that (in this scene, at least) Mofftiss are critiquing their own show in a straightforward sense, because they have dealt with technology better than this (words on screen, technology as useful within mysteries), drugs better than this (John’s, Mycroft’s and Molly’s reactions to Sherlock’s behaviour as well as Sherlock’s own difficulties) and clever quips far better (pick any episode). But in deconstructing this show to its instantly recognisable elements, and making them worse to hyperbolise the point, that scene strips the show of its heart. Interestingly, it’s also stripped of John, who will be the metaphorical heart of Sherlock through the EMP, but is also the part of the show that is missing when it is caricatured as the Benedict-Cumberbatch-being-clever show. This is also a critique of most people’s perception of Sherlock Holmes as a character through history in the sense of the reductive cleverness – Mofftiss are showing us that this is completely empty.

What does this mean for Sherlock himself, bearing in mind that this is taking place in his Mind Palace? The answer is pretty grim – remember that Sherlock is metatextually grappling with his own identity at this point; he needs to discover the man he is, rather than is portrayed as, in order to get out of this alive. In a psychological sense, then, the opening of TST sees Sherlock deconstruct himself as seen from the outside, and as his psyche has traditionally perceived himself, and realise that that version of himself is hollow. This scene, then, is a rejection of the Sherlock of the public eye, as well as Sherlock’s own eyes.

There is a non-explanation for how the Secret Service doctored the footage of Sherlock shooting Magnussen, the response simply being that they have the tech. If the answer is going to be that vague, there is little reason to bring up the question – except to raise it in the viewers’ minds. Making the audience question their belief in the s4 universe is something that happens very frequently, and this is the start of it. A later chapter goes into the parallels that Sherlock and Doctor Who have, but there’s an important bit from Last Christmas (DW Christmas Special 2014) that is relevant here – the main characters, all dreaming, whenever they are asked any questions that can’t be explained in the dream universe, simply reply ‘it’s a long story’. This is a ‘long story’ moment – where no explanation is given, so questions about reality are raised and unanswered.

Another similar moment comes when Sherlock says he knows exactly what Moriarty is going to do next – how? And, more to the point, it becomes hugely obvious that he doesn’t. Yet, for the first time in history, he feels happy to sit back and wait on Moriarty, because he knows that what will come will come. This insistence that the future will take its course as it needs to might draw our minds ahead to the frankly ridiculous reliance on predictions that we see in TLD – however, it should also draw our minds across to Doctor Who, and to Amy’s Choice, a series five episode I’m going to delve deeper into later, but where because it’s a dream, the Doctor is able to predict every word the monsters say.

Notice that ‘glad to be alive’ is followed by Vivian saying her name – we’ll come back to this later.

Cue opening credits!

Before going anywhere else with TST, required reading is this meta by LSiT (X). I can’t make these points better than she has, nor can I take credit for them. I’m particularly invested in her description of the aquarium and the Samarra story, as well as the client cases that appear and aren’t updated on John’s blog. Our reading will diverge later on – I think this series is a lot more metaphorical than it is hypothesis-testing, although the latter is a notable feature of ACD canon (see the original THotB) that definitely does happen here as well. I’m going to leave the Samarra story, the aquarium and the cases for LSiT to explain, however, and move on.

When we move into 221B, the fuckiness is instantly apparent from the mirror. You can go here (X) to navigate the whole inside of 221B, and I suggest you do; it’s a fantastic resource. The mirror showing the green wall is simply wrong – the angle that this is shot from suggests that we should see the black and white wallpaper, complete with skull etc. Instead, we see the green wall – and the door. We can tell this is wrong because in the ‘wrong thumb’ case about thirty seconds later, the right wallpaper is reflected in the mirror. Another note of fuckiness that we should spot is that Sherlock seems to be taking his cases from letters, in the mail he has knifed into the mantelpiece – this show has been really keen on emphasising that he uses email for the last three series, so the implication that people are sending him letters is even odder than it would be in a modern show anyway.

(Everybody in the world has commented on the ‘it’s never twins’ line – but to reiterate its importance. Firstly, it’s almost identical to the line in TAB, just with ‘it’s’ instead of ‘it is’. TAB repeats lots of things though, because it’s a dream – well yes, but dreams can’t tell the future. So material from TAB being recycled doesn’t point to TAB being a dream, it points to TST being a continuation of the dream in TAB. The fact that they saw fit to reiterate this line in a series about secret siblings also puts paid to the theory that s4 was plotted in a rush and not in line with previous series – there is a theme here, and they’re pushing it.)

And so we move to Sherlock relentlessly texting through the birth, through the christening – horrible, ooc behaviour for him if we think back to how emotional he was at the wedding. Importantly, this behaviour is all tied up with his obsessive Tweeting, which in turn links in to how the outside world (i.e. us) perceive Sherlock – is this the Sherlock that people want to see on screen? Doesn’t he feel wrong? Sure, there’s an element of self-critique in there from Mofftiss, but the incorporation of the phone obsession leaves the blame squarely with the audience. In case we couldn’t already feel that Sherlock’s character is way off, we have his Siri loudly say that she can’t understand him.

We remember from TAB that Sherlock sees himself as cleverer through John’s eyes, and the reasonably sympathetic portrayal we get in TAB we can probably put down to this attempt at understanding himself from the outside. The water in TST is showing us that we’re going in, and the sad thing is that this is almost definitely how Sherlock has come to perceive himself, but just like Siri he doesn’t truly recognise it. It’s also worth noting here the emphasis placed on God in godfather and later the deliberate mentions of Christianity at the Christening – there is also a tuning out of a culture he can’t really align himself with here, which is more important when we think about the fact that this character has been around since the 19th century.

Water tells us we’re sinking deep into Sherlock’s mind, as discussed in a previous chapter. Water imagery is going to be hugely prevalent in TST, but I want to talk quickly about the subtle hints at water even when we’re not in a giant fuck-off aquarium. Take a look at the rattle scene (which always sparks joy). When we get a side angle that shows both Sherlock and Rosie, there’s a black chest of some description behind Rosie – the top is glowing slightly blue, for reasons I can’t fathom. Then we’re going to cut to a shot of Rosie – despite seeing only a second before that there is nothing on her head, there is a glow of blue on it that looks almost like a skullcap. Cut back to Sherlock getting a rattle in the face, and the mirror is glowing the same blue colour behind him. This is all fucky, and it’s a fuckiness which is aesthetically tied to the waters of Sherlock’s mind perfectly. It suggests that Rosie isn’t real, but more important is the mirror. Earlier on I pointed out how the mirror was showing the wrong reflection; here, the mirror is glowing blue, linking it thematically to Sherlock’s subconsciousness. Visually, we’re being hinted at the process of self-reflection that’s going on in Sherlock’s brain – and the opening of TST is showing him getting it terribly wrong. Note that when the mirror jolted right earlier, Sherlock was proclaiming that it had been the wrong thumb – god knows what thumbs have to do with this, but there’s a question of shifting perception on his person, like he’s trying to locate himself.

The glowing blue light sticks around, and seems particularly associated with Rosie, like she’s the focus of much of Sherlock’s thought at the moment. LSiT’s meta linked above has already picked up on the many dangers in Rosie’s cradle decoration, from the Moriarty linked images to the killer whale mobile. Due purely to a lucky pause, I caught the killer whale’s eyes glowing blue, just like the blue from the rattle scene. He’s thinking about her in terms of the key villains of the show as well as the villains in his mind.

I’m not going to comment on the bus scene because I have a chapter dedicated to Eurus moments before TFP – jumping straight ahead.

We then find our first Thatcher case – others have been pretty quick to point out the significance of the blue power ranger in gay tv history (X), and infer that Charlie is queer coded – much like David Yost, who played the blue power ranger, he is not able to come out without being treated badly. This is undoubtedly important, as is the fact that this is the second time in 12 minutes of this show that they’ve shown us how easily film footage can be faked, and someone can be lied to – you don’t need to have Mycroft Holmes levels of clearance, just a Zoom background. This is important too. But the other thing I want to focus on is that he says he’s in Tibet.

Sherlock comes pretty high on my list of top TV shows, but currently Twin Peaks holds the top spot – it’s an unashamedly cryptic show all about solving mysteries through dreams, so no wonder I like it. It’s made by David Lynch, and in the TAB chapter I talk about how TAB takes a lot of structural inspiration from his most famous film, Mulholland Drive, which has similar themes. I don’t think this is anything particularly interesting beyond an attempt to reference the defining work in the field of it-was-all-a-dream film and tv – David Lynch and Mofftiss and Victor Fleming are the only people I can think of who can actually make that plot look good. But this Tibet moment, particularly as we’re going to be hit by another reference to Tibet later, underlining its importance, I think is a reference to this scene (X) where the protagonist, Cooper, outlines a dream in which the Dalai Lama spoke to him and gave him the power to use magic to solve mysteries. Fans of Twin Peaks will know that the magic doesn’t last long – it’s pretty much an introductory way in, and most of the rest of his important deductions will all be made in dreams. This is one of the most famous scenes in the whole programme, because it introduced the world to the weirdness of what had been set up as a straightforward cop show, and despite Cooper rarely (possibly never?) mentioning Tibet again, it’s still highly quoted and recognisable. As a watershed moment in bringing dream worlds into normal detective dramas (something highly frowned upon according to any theory of storytelling!) this is a gamechanging moment, and I don’t think it’s a stretch to point to Sherlock’s several references to Tibet as a link back to this moment.

We then cut back to Sherlock thinking whilst Lestrade tells him more about the case – what is bizarre here, is that John and Lestrade are clearly visible through what can only be described as a rearview mirror attached to the side of Sherlock’s head. If anyone can tell me what that is, I would love to know. I’m going to assume it’s a fucky mirror, because it’s in keeping with the other fucky mirrors so far. The visibility of John and Lestrade in the mirror is even more odd because it doesn’t match the colour palette of 221B at all. Sherlock is lit largely in warm, brown colours, as is Charlie’s father in the previous scene we’re transitioning from – Lestrade and John are lit in dark blue, to the point where they’re barely visible. This looks like a rearview mirror, but not like the one on the power ranger car – it’s a much older car, out of a different time, like so much in this dream world. The only colour palette they seem to match is the one from the s4 promotion photos – you know, when Baker Street is completely underwater.

Drowning in the Mind Palace. Here we are, back where we started. Sherlock might be thinking about the case of Charlie, but he’s actually reflecting on that world we saw in the promo photos, where he’s struggling to stay alive in his brain. Notice that this isn’t just a split shot, it’s specifically a mirror, so we’re meant to focus on this episode as an act of reflection. There are great parallels between Sherlock and the Charlie case which you can find here (X) – essentially, Charlie and Carl Powers from TGG are mirrors for one another both in their names and in the manner they die (a fit in a tight place, basically). Carl Powers is already a mirror for Sherlock – obsessively targeted by Jim for being the best at what he does. Charlie mirrors Sherlock through their shared trip to Tibet (dreamscape alert) and, we think, through the metatextual link of the blue power ranger. In case you hadn’t spotted it, Powers links back to that too – probably coincidence, but a nice one nevertheless. Carl Powers’s death is by drowning, which we shouldn’t ignore in an episode as loaded with ideas about drowning in the mind palace. The fact that the mirror reflects drowning Baker Street aesthetics should make us think that Charlie is asking us to reflect on Carl Powers’s death, but also on Sherlock’s own – already fatally injured (by a fit or by Mary), he is going to die smothered, unable to cry for help (in a swimming pool/carseat costume (?!)/mind palace). The idea that none of these people could cry for help is particularly poignant because so much of series 4 is about Sherlock being unable to voice his own identity, and as we’ll see once he’s able to do that, that may give him the impetus to escape his death. Think of ‘John Watson is definitely in danger’ back in HLV.

Now. Why is Sherlock so keen for Lestrade to take the credit? It’s another reason to bring up the fact that John’s blog is constantly updating – it’s dropped in a lot in this series as opposed to others – and to make us think about why nothing is happening in real life. But, given that this episode is about Sherlock trying to find who he is, is it a rejection of the persona that goes along with being Sherlock Holmes? Possibly, but he’s going to have to go to a lot more effort than that. John’s blog is the real problem here, making not just Sherlock but Lestrade out to be like they’re not. John’s blog is a stand in for the original stories, which were supposed to be written by John Watson, but TAB has already (drawing on TPLoSH) laid the groundwork for the idea that John’s blog/those stories really do not tell the whole story. So this is coming back with a vengeance here, even though for the first time Sherlock is properly moving against the persona in there, not just bitching about John’s writing style, which is a theme more common to Sherlock Holmes across the ages. John then says that it’s obvious, and when pressed just laughs and says that it’s normally what Sherlock says at this point – so again, when Sherlock stops filling the intense caricature of arrogance and bravado, John the storyteller steps in to put him back in line, even though that means pulling him back to being a much more unpleasant character.

A note here: most of the time in EMP theory, I think John represents Sherlock’s heart, and I try to refer to John as heart!John as much as possible when that’s the case. There are a few cases which are different, but most notable are when the blog comes up – then John becomes John the blogger, and our symbolism shifts over to the repressive features of the original stories and how that’s playing out in the modern world. Although a pain to analyse sometimes, I find it incredibly neat that the two of them are bound up in John as source of both love and pain, which fits our story beautifully.

John as blogger continues in the baby joke that he and Lestrade have going down the stairs – they continue with their caricature of Sherlock, but he doesn’t recognise himself in it. Or rather, there’s a moment when he seems to, but he can’t quite grasp onto it. This is typical of the way he recognises himself in the programme. It’s also worth noting that the image of John as a father is particularly tied into ACD, as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, so tying together blogger and father in this scene cements our theme.

Going into the Welsborough house, we get a slip of the tongue from Sherlock which is fantastic. He tells them that he is really sorry about their daughter, which at an earlier point in the show might just be a classic Sherlock slip-up. But mixing up genders is actually something which happens quite a lot in this show, and it’s something drawn attention to as significant in TAB.

Sherlock asks John “How did he survive?” of Emelia Ricoletti, when of course he’s thinking about Moriarty, and John corrects him quickly, much like here. A coincidental callback? Maybe not. What’s the first mistake that Sherlock ever makes? Thinking that Harry Watson is a man. What’s the big trick they pull at the end of S4? Sherlock has a secret sister – and Eurus points out that her gender is the surprise at the end of TLD. Eurus is also an opposite-sex mirror for John and for Sherlock at various points and this allows Sherlock to approach their relations from a heterosexual standpoint and thus interrogate them – more on that later. So gender-swapping is a theme that runs through the show a lot. But the similarity to TAB in particular is important here, because in TAB that was our first obvious declaration that this wasn’t just a mirror to be analysed by the tumblr crowd, this was a mirror on the superficial level that had to be broken through. This callback to TAB is a callback to the mirrored dreamscape. Don’t believe me? Look at what happens next. The second Sherlock sees Thatcher the whole room not only goes underwater, but actually starts to shake – another throwback to recognising that Emelia was Moriarty, when the whole room shakes and the elephant in the room smashes. So, again, we’re being told that this isn’t about this case – it’s about something else, and that something is the elephant in the room. Just like the shaking smashes the elephant in the room, the shaking is what tells us about the smashed bust of Margaret Thatcher. Margaret Thatcher, whose laws on “promoting homosexuality” were infamous. Smashing the elephant in the room and Thatcher simultaneously between 2015, the 1980s and 1895 is hitting the history of British homophobia for the last hundred years summed up as quickly as possible, and tearing it down through Sherlock’s self-exploration. This is a good fucking show.

You’ll also notice that Sherlock is alone in the room, just for a second, when he has his Thatcher revelation – everybody else vanishes. Again, we’re seeing that the rest of the case is an illusion, providing just enough storytime to keep the audience believing in the dream, and possibly Sherlock too.

[There’s a fantastic framing of Sherlock here between two portraits, a man and a woman, seemingly ancestral – I would love to know more about these, because if I know Arwel they’re significant, and the way they hang over Sherlock is really metaphorically suggestive. If anyone has any info on that, it looks like a really good avenue to explore.]

Blue. Blue is the colour of Sherlock’s mind palace, but this scene ties it firmly to the Conservative party. The dark blue of Sherlock’s scarf nearly matches Welsborough’s jumper, which is in fact a better match for the mind palace aesthetic generally. Thatcher unsurprisingly wears blue as well. If blue is the water that Sherlock is drowning in, how interesting that it’s being tied to the most homophobic prime minister of the last 50 years. There was absolutely no need to make this guy a cabinet minister, dress him in blue, even make Thatcher replace Napoleon – I would actually argue that Churchill is a figure who matches Napoleon’s distance and stature much better for our time. Thatcher is an odd choice, and therefore significant. To tie this to the mind palace further, we then get a shot of Sherlock reflected in the picture of Thatcher as he analyses it – a reflection of him reflecting. In case we forgot what this was actually about.

Sherlock not knowing who Thatcher is – perfectly feasible and actually quite important, although something that I’m not going to resolve until my meta on TFP, because that’s where it comes together for me. But Sherlock playing for time with his further jokes about being oblivious (‘female?’) – that, again, is Sherlock actively playing a caricature of himself. He’s not doing it for fun – he’s doing it to cover up his concern about the smashed elephant in the room Thatcher bust.

The weird thing about the reveal of how Charlie died is that we see what should have happened, if everything had gone right, before we see how he died. I can’t recall this happening in another episode of Sherlock, although I could be wrong. It’s marked by the really noticeable scene transition of crackling television static, as though the signal is cutting out. This is possibly a bit of a reach, but there’s one obvious place where we’ve seen a lot of static before.

Moriarty coming back isn’t what’s supposed to happen. It doesn’t happen in the books. We’re telling the wrong story here. (Bear in mind, from previous chapters, that Jim represents Sherlock’s fear that John’s life is in danger.) Just like Jim returning isn’t the right story, but it’s the one that happened, Charlie’s story isn’t the right story but it’s the one that happened – and indeed, Sherlock needing to save John from a dangerous marriage + suicide is not what is supposed to happen – John and Mary are supposed to be married for good (until she dies) in canon. A whole load of false endings – new stories superseding old ones. Mofftiss has an idea that there’s a new story that’s going to be told, and our strongest canon divergence is the end of s3, when we get into the EMP – and from thereon in to TAB it’s off the deep end, and the same is seen here. That TV static is talking about a new medium for a new age and their refusal to deal with established canon norms. Just in case we didn’t remember, outside in the porch we even get a visual reminder of the TV static with a second’s flashback to ‘Miss Me?’ Bad news is, that means Sherlock Holmes rejecting the norms he’s been given (feasibly represented by the hyperbolic nuclear family here) and instead… dying in his mind palace. Less fun. Carl Powers died too. Sherlock still hasn’t got there quite yet – let’s hope he doesn’t.

The next scene is, I think, very important. We come across Mycroft in a dark room with a tiny bit of light – this is really odd, as the obvious place to put Mycroft would be the Diogenes Club. Yet, although clearly more modern, this reminds me most of all of the room we meet Mycroft in in TAB.

The colour palette is the same as the top photo, and the similar chunks of light falling through suggest that we’re in the same place. I’ve brought in a photo from the aeroplane in TAB to show how the light is designed to mirror that of the Diogenes Club in TAB as well – there is a unity in all these Mycroft’s that we shouldn’t miss. Here I can’t imagine I’m the first one to notice that the light in Mycroft’s office is designed to look like a chessboard, which was an important motif in the promotional pictures for s4. Chess is associated with Sherlock’s brain through Mycroft, most notably in THE where it is contrasted with Operation which represents their emotional (in)capacities. So here we are – Mycroft is the brain, if we didn’t already know, and Sherlock has gone to speak to his brain alone much like he did in TAB. Mycroft has already been associated with the queen a lot; they meet in Buckingham Palace in ASiB, where there is a jibe about Mycroft being the queen of England – we can see here in Sherlock’s head that the brain’s power is vastly reduced by comparing these two episodes. The first time we see Mycroft in connection to the Queen we go to the most famous building in the UK. The second time, Sherlock says he’s going to the Mall, which is the street that Buckingham Palace is on, so we are led to expect a reprisal – and instead come here. There is still a picture of the queen on the wall, but apart from that we are in the darkest room of the show so far, whose grating makes it look under siege. Mycroft’s power in Sherlock’s head is vastly reduced, and indeed the brain’s influence (represented by the queen) over Sherlock’s character is waning as Sherlock struggles to come to terms with his emotional identity.

[Crack/tenuous theory: when Sherlock asks John if he is the king of England in s3, in the drunk knee grope scene, this shows that his brain’s control over his emotions have slipped; references to the queen in relation to Mycroft before have shown that Sherlock does know about the royal family, so this has to metaphorically refer to his own psyche and letting go of his brain’s anti-emotion side. Like I say, crack. But I believe it.]

Again, if we weren’t sure about Mycroft representing the brain without the heart, his rejection of the baby photos is sending out a clear message of juxtaposition with John, who represents the heart. We also shouldn’t fail to notice the water coming over Sherlock’s face again as he struggles to recognise what is important about this. This comes as he is trying to recognise what is important about the Thatchers case. I’m going to try to lay it out as best I can here.

We’ve been through what Thatcher represents to queer people of Sherlock’s age, so there’s already a strong metaphor for homophobia being smashed there. However, let’s look at the AGRA memory stick being uncovered. We know (X) that Sherlock deduced his feelings for John as he was marrying Mary, and so having the smashing of the Thatcher bust at the AGRA memory stick reveal is pretty devastating metaphorically. Why does Sherlock constantly think Moriarty is involved? Well, HLV tells us that the Jim in Sherlock’s mind is his darkest fear – and he’s originally tied up in Sherlock’s mind when he’s first shot, but he pretty quickly gets loose. That darkest fear is exactly what Jim says in that episode: ‘John Watson is definitely in danger’. The reason we bring Jim in to represent this is part of deconstructing the myth of Sherlock Holmes. The whole concept of an arch enemy is made fun of in the show, and rightly so; Moriarty himself tells the Sir Boastalot story which lines Sherlock up with that ridiculous heroic tradition that he’s set himself into, which isn’t what Sherlock Holmes is really about at all. Holmes has never really been particularly invested in individual criminals (although there are exceptions – Irene Adler, for example) – the time he gets most het up is The Three Garridebs, as we all know, when he thinks Watson is dying. It’s his greatest fear, and it’s also what Jim threatens, so Jim has become a proxy for that – and to understand that Sherlock Holmes is not the great Sherlock Holmes of the last hundred years, we have to get under and beyond Jim. Hence what we’re about to see. It’s not Jim, it’s Mary – and this is in very real terms, because Mary’s assassination attempt on Sherlock has left John in danger – but Sherlock won’t put the pieces together until the end of this episode, as we will see.

We should also pause over Mycroft asking Sherlock whether he’s having a premonition – Mycroft is laughing at the concept of Sherlock being able to envisage the future here, which we should remember when it comes to the frankly ludicrous plot of the next episode. Much like the much commented upon “it’s not like it is in the movies” which is there to undermine TST, this line is here to undermine TLD and point out the fact that it can’t possibly be real.

Sherlock describes predestination as like a spider’s web and like mathematics – both of these are to do with Moriarty. In the original stories, Moriarty is a mathematician, and one of the most famous lines from both the stories and the show describes Moriarty as a spider. This predestined future is one that Sherlock doesn’t like – Mycroft points out that predestination ends in death, which is what Sherlock is trying to avoid in this episode, and although Moriarty is never mentioned explicitly, his inflection here suggests that Sherlock is thinking about John subconsciously, without even understanding it. The Samarra discussion brings us back to the question of Sherlock’s death, and links it in with the deep waters of the mind he’s currently drowning in – the pirate imagery becomes really important here, because a pirate is someone who stays alive on the high seas and fights against them. The merchant of Samarra becoming a pirate is not merely a joke about a little boy, it’s a point about fighting for survival – and how will Sherlock later fight for survival? We’ll see him battle Eurus (his trauma, more on that later) head on, literally describing himself as a pirate. Fantastic stuff.

The scene transition where all of the glass breaks and then we cut to a background of what looks like blue water is a motif that runs through this entire episode – we’re smashing down walls in Sherlock’s mind, most particularly the Thatcher wall of 1980s homophobia, and indeed the first picture we see is that of the smashed bust.

Moving on – before we go back to Baker Street, there’s a shot of the outside – that features a mirror, reflecting back on 221B in a distorted, twisted way. Another mirror that is wrong – we’re reflecting in an alternate reality. These images keep popping up. It’s echoed in Sherlock’s deduction a few seconds later – by the side of his chair is what looks like either a car mirror or a magnifying glass, possibly the one from the Charlie scene, distorting his arm. It’s placed to look like a magnifying glass, whether it is or not, which ties in with the classic image of Holmes – but that image is distorted, remember.

Others have pointed out that when Sherlock falsely deduces that the client’s wife is a spy working for Moriarty, he should really be talking to John – and, in fact, this is another proof that this isn’t really, because otherwise this is pretty touchy stuff to be making light of in front of John. Instead, let’s remember this is Sherlock’s Mind Palace – John isn’t John here. What Sherlock does a lot in s4 – and nowhere more than the finale of TST – is displace a lot of his real world problems onto other people because he cannot handle the emotional impact of them, and that’s what he’s doing here. He’s trying to come to terms with the danger that Mary poses, but he can’t do it with John – hence why this scene has a John substitute, because that’s what the client is.

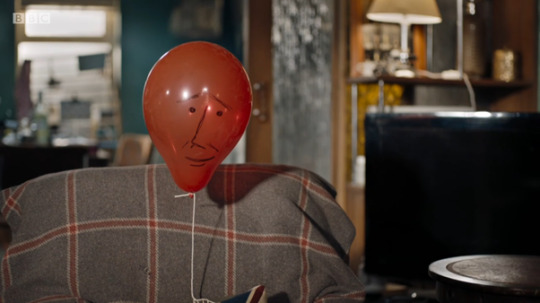

Note that the red balloon is over the Union Jack cushion, reminding us that this scene is about John in danger (see this post X). However, what’s important here is that Sherlock has got it wrong. He’s currently trying to work out why what has just happened with Mary poses so much danger, and he’s imagining Mary as the worst threat he possibly could – in a word, this Mary is a supervillain. But Mary is not a supervillain; he’s got this all wrong, and even as he says it, it’s completely ridiculous. This is not the danger Mary poses – and so out the door the client goes, and we’re back to square one, trying to work out exactly why John is in so much danger.

I’m not going to pause over the next moment of importance for too long because many have covered it – let’s just notice that Sherlock’s face is overlaid with a smashed Thatcher bust, and remind ourselves that these are the walls of homophobia in Sherlock’s brain. Also note that this matches the half-face overlay of the water in the previous scene, linking the two (although the scene with Ajay later will cement that anyway).

Next up: Craig and his dog. Nothing can be said about dogs that hasn’t be said in these wonderful metas by @sagestreet (X). Nevertheless, let’s note that this dog is coloured the same as Redbeard, and Mary (a Sherlock mirror in this episode, and in this scene – their clothing matches, and their joining of skillsets to exclude John is the link that has always united them as mirrors) compares John to the dog. We know from the metas linked above that dogs are linked to queerness in the show, but let’s remember that John here is not John – John represents Sherlock’s own heart. It’s going to take longer than this for Sherlock to acknowledge John’s queerness. I don’t think Toby the dog is that important – instead, this is foreshadowing for the more significant dog to come in TFP. The dog also allows for another bit of self-parody in the show – the close-up on the dog running through chemical symbols and the map link directly back to the chase scene in ASiP, but this time everything is different. We have no clue really what Toby is chasing or what the crime that has been committed is – they’re not even running, they’re walking! All we have are cool, if ridiculous, graphics – and, brought down to style without substance, it’s nothing but comic parody. This is important because the opening of TST is so parodic – we’re back to questioning whether the things that people associate with Sherlock and think they like about Sherlock are the right things. The fact that Toby reaches a dead end here is important – he’s a weird loose end to have hanging through the episode. When things in Sherlock normally tie together so nicely, this is a section which has absolutely no bearing on the rest of the plot other than to look a bit silly. But fundamentally, we’re talking about the superfluity of style and image here; we’ve been talking about it for a long time in relation to previous adaptations, but TST brings it in in relation to Sherlock itself.

Skipping past more bust breakages, the next scene is John and Mary in bed together – and the first thing we see is them, once again, in a mirror. There’s nothing wrong with this mirror (as far as I can tell) – everything seems to be in order! But it doesn’t break the theme of mirrors misreflecting, because this is the scene that introduces unreliable narration on a big level – this is the scene which deliberately excludes John’s texts to E. John and Eurus are gone into in another chapter so we’ll move on again.

Craig’s quote about people being weird for missing the olden days is, of course, crucial to this reading of Sherlock. It’s pretty on the nose for a show whose protagonist is idealised in the Victorian age – and sums up Mofftiss’s feelings towards the Vincent Starrett 221B poem that I elaborated on in the TAB chapter of this meta: essentially, that it always being 1895 is a very bad thing! Craig’s mockery of this nostalgia puts it into more comprehensible modern terms for us, but it also links Thatcher and 1895 again as pasts to be broken with. It’s also important that Craig says that Thatcher is like Napoleon now – although the titles of most episodes are taken from ACD stories, it’s rare that an explicit reference is made to the link between the titles (nobody mentions scarlet vs. pink in ASiP, for example). This is the first time that I can find that Sherlock shows self-awareness from within the narrative that there are extranarrative stories being played out. I’ve said before that I don’t think Thatcher and Napoleon are a good comparison; whether it is or not, Craig’s reference is actively pulling a metatextual part of Sherlock’s history into his story and forcing him to reckon with it. This is important, because he develops expectations of how this story is going to play out (black pearl of the Borgias) which are wrong – because they’re based on what he has learned to expect of himself as fictional character. We could only have such a reference within the Mind Palace.

For the sake of splitting this meta up to make it readable, I’m going to call time on this half of TST, and we’ll pick it up tomorrow at Jack Sandiford’s house. (Also I don’t know how much text tumblr allows and this is a long document.) Until then!

#emp#tst#tjlc#meta#bbc sherlock#my meta#mine#thewatsonbeekeepers#chapter six: so long and thanks for all the fish#tjlc is real#emp theory#the six thatchers#johnlock

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

thoughts on the beguiled.

I’ve wanted to watch The Beguiled since I saw the trailer for it in 2017, but I never ended up seeing it. I also didn’t hear much hype around it in the 19C US lit academic community, which I was definitely a part of at the time of its release. I saw–I think–a Vogue article on it, and a few articles came out about the costuming or historical setting. It was directed by Sophia Coppola, so that carries some weight–or it should have. I can’t speak much to the film’s popular success, but I can say that it wasn’t a thing in academia. That surprises me now, especially given how popular the recently released Green Knight movie has been in the medieval academic internet. Maybe The Beguiled didn’t get much buzz because it’s a remake, so anyone who would’ve hyped a movie in 2017 had already seen the original, or maybe it’s just that 19C US lit academia hasn’t come to fully appreciate films about that time period (I’m not sure I buy that because everyone had something to say about the most recent Little Women adaptation). Basically, I’m surprised the 2017 The Beguiled wasn’t required viewing for every PhD student in 19C US lit in the same way that literally any single one of the Little Women or Anne of Green Gables adaptations has proven to be. Is it because The Beguiled focuses on the South? Is it because it’s a remake? I don’t know, and now that I’m not in academia, I’m not sure I really care. It’s just a casual thought that prompted this post.

If you haven’t seen or heard of The Beguiled, it’s like Misery meets Little Women but set in the Civil War-era South. The recent adaptation stars Kirsten Dunst, Nicole Kidman, Elle Fanning, and Colin Farrell. The basic premise is that Colin Farrell’s character is a Union (Northern) soldier (originally of Irish descent) who is wounded in battle and hides in the woods to die or … recover? He’s found by a young Southern girl who’s attending an all-girl’s boarding school in the area; she’s out picking mushrooms, finds him, and brings him back to the school so the headmistress can care for him. The five or six other female students at the boarding school–and the headmistress–quickly become enamored with Colin Farrell and begin competing for his affections. They heal his leg, and he begins reciprocating everyone’s attention. He tells Kirsten Dunst he loves her, he shares a few heavy emotion moments with Nicole Kidman, and he flirts repeatedly with Elle Fanning–all while the other girls and women are in the room. It’s bold behavior, but what does he have to lose? Well, actually, a lot because Kirsten Dunst finds him one night in bed with Elle Fanning, and when he approaches her to apologize or explain (honestly, what is his goal????), she pushes him away from her–and down the gigantic plantation house’s stairs. He’s knocked unconscious and his sutured leg injury reopens, so Nicole Kidman decides to amputate because he’s losing a lot of blood (but actually because she’s jealous that he went to Elle Fanning’s bedroom). He awakens from the surgery and is BIG MAD. He calls everyone on their bullshit but also goes into a drunken rage because he only has one leg and the amputation was performed for, frankly, illegitimate reasons. Kirsten Dunst tries to calm him down by having sex with him, but the other women plot how to get rid of him (oh yeah, he grabbed a weapon–I missed how he got it. Did he already have it? I thought Nicole Kidman had one too?), and they decide to have Mushroom Girl go get the bad mushrooms. They feed them to him, he dies, and the leave his body outside the gate for whichever army to pick up as they pass. That’s it. That’s how the movie ends.

I liked this movie; it was fine. Was it what I’d hoped for from Coppola? Not at all. Marie Antoinette is one of my favorite movies and I always how Coppola will make films in that same style. The Virgin Suicides has a lot of that same energy, and I love that film too. The Beguiled definitely feels like a Coppola movie. It has a similar dreamy and ethereal quality, but here there’s a darkness and underlying tension that some of the (literally) brighter films don’t always have–visually, at least. Or, maybe a better way of putting it is that the true bright, dreamy, and ethereal scenes are fewer and further between in The Beguiled than they are in the other two films I mentioned. Whereas the dark, saturated tones appear pretty much throughout in The Beguiled (except in a few very key moments), Marie Antoinette and TVS are dominated by those bright, dreamy, ethereal tones, and the darker, saturated tones appear in very strategic moments to signal Serious Business happening. As a viewer, I don’t mind the difference, but I’m not sure if the dark, saturated tones in The Beguiled always accurately reflect other depths of the film–most notably, its plot. But more on that in a second.

To get the thing out of the way that I’m supposed to talk about as someone with a PhD in 19C US lit, the historical stuff in this film works. It’s not trying to be irreverent or fanciful with historical tropes like, say, Marie Antoinette. That’s not a value judgment; it’s just a comment. Frankly, I don’t really have too much to say about this film’s historical aspects. Whereas I usually have some opinion of costuming (the recent Little Women adaptation is wonderful but there are … things I don’t love) or how historical subject matter from the period gets treated in films, in this case, I really wasn’t distracted by any significant historical inaccuracies and there were only a few times that I was like “wait a second, is this right???” Honestly, the biggest cause for that question related to some of the evening wear, which looked a little cheap, but that’s whatever; also, Civil War-era garments aren’t something I know especially well, so who am I to judge?

I appreciated the film’s take on women’s–well, some women’s–concerns during the Civil War, including the threats posed by roving military troops on both sides of the conflict, the loss of loved ones (and the sense that their lives are halted but also must go on), the mindless regurgitation of stereotypes about enemy soldiers, etc. I also love the way the film portrays some of the more mundane aspects of these women’s lives–the monotony of sewing, housework, and learning French to speak … with one another–and some of the unique situations caused by wartime population changes, including middle- and upper-class women’s need to perform outdoor labor (I was surprised to see them using shovels, for instance).

I was, frankly, extraordinarily disappointed to see that the film pares the household economy down to a group of middle- and upper-class white women with a casual comment about how all of the enslaved workers left prior to the film’s opening. I understand that this detail further emphasizes how alone and isolated this group is, but for a film released in 2017, it frankly felt like a cop-out. It’s unfathomable to me that a Southern Gothic film set during the Civil War wouldn’t have one single Black character and could write an entire population off in a throw-away line at the beginning of the film. Black Americans played essential roles in the US economy during this period–in all periods, but I’m talking about this one specifically here–and they were pivotal figures in the Civil War itself. They held especially pivotal roles in the South’s (really, the nation’s) economy, and their relationships with domestic life in that region were so complex, rich, and, frankly, worthy of all the attention in the world. Did the film’s producers not want to hire more actors, or did they think a group of white people having old-timey white people problems was enough to bring in audiences? The 19C was full of a million different stories of how enslaved southerners responded to the war and how their lives changed–especially in the South–because of it, so to not depict even one of those stories strikes me as … well, representative of what’s wrong with this film.

Okay, so I lied when I said I didn’t have an opinion on the historical stuff in this film.

My big issue with the film–well, other than (or connected with) the fact that it completely ignores literally the most important population of society during the historical moment it depicts–is that this film’s content doesn’t seem to live up to its visual richness and depth. What I mean by this is that the film’s deep and rich visual style–the color saturation and tones mentioned above–don’t mesh with the plot and characters, which are collectively underdeveloped. I think the underdeveloped plot is fairly straightforward–I didn’t need to leave much out in my summary above, and that paragraph is shorter than most emails I send. This is a film without subplots, which has made me realize how important subplots actually are for fleshing out a fictional world–even a fictional world I know a lot about and am able to imagine my own depth for. The story is a love triangle (with a few extras) in the South during the Civil War. That love triangle could take place literally anywhere and anytime else and it’d have basically the same tension. I’m not even sure you really even need the enemy soldier dimension of Colin Farrell’s character because it’s barely an issue; the majority of the tension comes from the threat a man poses–even an injured one–to a group of women, and that’s timeless. We, as a society, are also obsessed with the idea of women fighting for a man, a storyline I’m getting a bit sick of because it’s just another way we pit women against one another. But that gets to something else, which is the lack of character development. The characters–all seven of them or whatever–are stereotypes. Kirsten Dunst is the shy one who underestimates her beauty, Colin Farrell is an undercover Casanova (a 19C fuckboy, shall we say?), Elle Fanning is a flirt, and Nicole Kidman is a stern (and vindictive) older unmarried woman. We also have the spoiled rich girl and the silly sweet (but also unexpectedly vicious) girl. And Mushroom Girl is the nature-lover, who we know will be expected to conform to societal expectations the second the war ends and she reaches a certain age.

Frankly, the most interesting part about this film is imagining what is happening and will happen outside of what it shows on screen. I spent the entire time I was watching it wondering what these girls’ families were doing, how the soldiers just beyond the camera shots were faring, what the home’s previous (enslaved) domestic laborers were up to and where they had gone (and what their lives were like here before the war), what would happen to the girls in the days and months following the events of the film, etc.

TL;DR: It’s a flawed film that wasn’t terrible to watch, but left me wanting more–a lot more, and not in a “oh, make a sequel!” kind of way but in a “what was left on the editing room’s floor?” kind of way.

xoxo, you know.

1 note

·

View note

Text

thoughts on the beguiled.

I’ve wanted to watch The Beguiled since I saw the trailer for it in 2017, but I never ended up seeing it. I also didn’t hear much hype around it in the 19C US lit academic community, which I was definitely a part of at the time of its release. I saw–I think–a Vogue article on it, and a few articles came out about the costuming or historical setting. It was directed by Sophia Coppola, so that carries some weight–or it should have. I can’t speak much to the film’s popular success, but I can say that it wasn’t a thing in academia. That surprises me now, especially given how popular the recently released Green Knight movie has been in the medieval academic internet. Maybe The Beguiled didn’t get much buzz because it’s a remake, so anyone who would’ve hyped a movie in 2017 had already seen the original, or maybe it’s just that 19C US lit academia hasn’t come to fully appreciate films about that time period (I’m not sure I buy that because everyone had something to say about the most recent Little Women adaptation). Basically, I’m surprised the 2017 The Beguiled wasn’t required viewing for every PhD student in 19C US lit in the same way that literally any single one of the Little Women or Anne of Green Gables adaptations has proven to be. Is it because The Beguiled focuses on the South? Is it because it’s a remake? I don’t know, and now that I’m not in academia, I’m not sure I really care. It’s just a casual thought that prompted this post.

If you haven’t seen or heard of The Beguiled, it’s like Misery meets Little Women but set in the Civil War-era South. The recent adaptation stars Kirsten Dunst, Nicole Kidman, Elle Fanning, and Colin Farrell. The basic premise is that Colin Farrell’s character is a Union (Northern) soldier (originally of Irish descent) who is wounded in battle and hides in the woods to die or … recover? He’s found by a young Southern girl who’s attending an all-girl’s boarding school in the area; she’s out picking mushrooms, finds him, and brings him back to the school so the headmistress can care for him. The five or six other female students at the boarding school–and the headmistress–quickly become enamored with Colin Farrell and begin competing for his affections. They heal his leg, and he begins reciprocating everyone’s attention. He tells Kirsten Dunst he loves her, he shares a few heavy emotion moments with Nicole Kidman, and he flirts repeatedly with Elle Fanning–all while the other girls and women are in the room. It’s bold behavior, but what does he have to lose? Well, actually, a lot because Kirsten Dunst finds him one night in bed with Elle Fanning, and when he approaches her to apologize or explain (honestly, what is his goal????), she pushes him away from her–and down the gigantic plantation house’s stairs. He’s knocked unconscious and his sutured leg injury reopens, so Nicole Kidman decides to amputate because he’s losing a lot of blood (but actually because she’s jealous that he went to Elle Fanning’s bedroom). He awakens from the surgery and is BIG MAD. He calls everyone on their bullshit but also goes into a drunken rage because he only has one leg and the amputation was performed for, frankly, illegitimate reasons. Kirsten Dunst tries to calm him down by having sex with him, but the other women plot how to get rid of him (oh yeah, he grabbed a weapon–I missed how he got it. Did he already have it? I thought Nicole Kidman had one too?), and they decide to have Mushroom Girl go get the bad mushrooms. They feed them to him, he dies, and the leave his body outside the gate for whichever army to pick up as they pass. That’s it. That’s how the movie ends.

I liked this movie; it was fine. Was it what I’d hoped for from Coppola? Not at all. Marie Antoinette is one of my favorite movies and I always how Coppola will make films in that same style. The Virgin Suicides has a lot of that same energy, and I love that film too. The Beguiled definitely feels like a Coppola movie. It has a similar dreamy and ethereal quality, but here there’s a darkness and underlying tension that some of the (literally) brighter films don’t always have–visually, at least. Or, maybe a better way of putting it is that the true bright, dreamy, and ethereal scenes are fewer and further between in The Beguiled than they are in the other two films I mentioned. Whereas the dark, saturated tones appear pretty much throughout in The Beguiled (except in a few very key moments), Marie Antoinette and TVS are dominated by those bright, dreamy, ethereal tones, and the darker, saturated tones appear in very strategic moments to signal Serious Business happening. As a viewer, I don’t mind the difference, but I’m not sure if the dark, saturated tones in The Beguiled always accurately reflect other depths of the film–most notably, its plot. But more on that in a second.

To get the thing out of the way that I’m supposed to talk about as someone with a PhD in 19C US lit, the historical stuff in this film works. It’s not trying to be irreverent or fanciful with historical tropes like, say, Marie Antoinette. That’s not a value judgment; it’s just a comment. Frankly, I don’t really have too much to say about this film’s historical aspects. Whereas I usually have some opinion of costuming (the recent Little Women adaptation is wonderful but there are … things I don’t love) or how historical subject matter from the period gets treated in films, in this case, I really wasn’t distracted by any significant historical inaccuracies and there were only a few times that I was like “wait a second, is this right???” Honestly, the biggest cause for that question related to some of the evening wear, which looked a little cheap, but that’s whatever; also, Civil War-era garments aren’t something I know especially well, so who am I to judge?

I appreciated the film’s take on women’s–well, some women’s–concerns during the Civil War, including the threats posed by roving military troops on both sides of the conflict, the loss of loved ones (and the sense that their lives are halted but also must go on), the mindless regurgitation of stereotypes about enemy soldiers, etc. I also love the way the film portrays some of the more mundane aspects of these women’s lives–the monotony of sewing, housework, and learning French to speak … with one another–and some of the unique situations caused by wartime population changes, including middle- and upper-class women’s need to perform outdoor labor (I was surprised to see them using shovels, for instance).

I was, frankly, extraordinarily disappointed to see that the film pares the household economy down to a group of middle- and upper-class white women with a casual comment about how all of the enslaved workers left prior to the film’s opening. I understand that this detail further emphasizes how alone and isolated this group is, but for a film released in 2017, it frankly felt like a cop-out. It’s unfathomable to me that a Southern Gothic film set during the Civil War wouldn’t have one single Black character and could write an entire population off in a throw-away line at the beginning of the film. Black Americans played essential roles in the US economy during this period–in all periods, but I’m talking about this one specifically here–and they were pivotal figures in the Civil War itself. They held especially pivotal roles in the South’s (really, the nation’s) economy, and their relationships with domestic life in that region were so complex, rich, and, frankly, worthy of all the attention in the world. Did the film’s producers not want to hire more actors, or did they think a group of white people having old-timey white people problems was enough to bring in audiences? The 19C was full of a million different stories of how enslaved southerners responded to the war and how their lives changed–especially in the South–because of it, so to not depict even one of those stories strikes me as … well, representative of what’s wrong with this film.

Okay, so I lied when I said I didn’t have an opinion on the historical stuff in this film.

My big issue with the film–well, other than (or connected with) the fact that it completely ignores literally the most important population of society during the historical moment it depicts–is that this film’s content doesn’t seem to live up to its visual richness and depth. What I mean by this is that the film’s deep and rich visual style–the color saturation and tones mentioned above–don’t mesh with the plot and characters, which are collectively underdeveloped. I think the underdeveloped plot is fairly straightforward–I didn’t need to leave much out in my summary above, and that paragraph is shorter than most emails I send. This is a film without subplots, which has made me realize how important subplots actually are for fleshing out a fictional world–even a fictional world I know a lot about and am able to imagine my own depth for. The story is a love triangle (with a few extras) in the South during the Civil War. That love triangle could take place literally anywhere and anytime else and it’d have basically the same tension. I’m not even sure you really even need the enemy soldier dimension of Colin Farrell’s character because it’s barely an issue; the majority of the tension comes from the threat a man poses–even an injured one–to a group of women, and that’s timeless. We, as a society, are also obsessed with the idea of women fighting for a man, a storyline I’m getting a bit sick of because it’s just another way we pit women against one another. But that gets to something else, which is the lack of character development. The characters–all seven of them or whatever–are stereotypes. Kirsten Dunst is the shy one who underestimates her beauty, Colin Farrell is an undercover Casanova (a 19C fuckboy, shall we say?), Elle Fanning is a flirt, and Nicole Kidman is a stern (and vindictive) older unmarried woman. We also have the spoiled rich girl and the silly sweet (but also unexpectedly vicious) girl. And Mushroom Girl is the nature-lover, who we know will be expected to conform to societal expectations the second the war ends and she reaches a certain age.

Frankly, the most interesting part about this film is imagining what is happening and will happen outside of what it shows on screen. I spent the entire time I was watching it wondering what these girls’ families were doing, how the soldiers just beyond the camera shots were faring, what the home’s previous (enslaved) domestic laborers were up to and where they had gone (and what their lives were like here before the war), what would happen to the girls in the days and months following the events of the film, etc.

TL;DR: It’s a flawed film that wasn’t terrible to watch, but left me wanting more–a lot more, and not in a “oh, make a sequel!” kind of way but in a “what was left on the editing room’s floor?” kind of way.

xoxo, you know.

1 note

·

View note

Text

My side project for story/lore updating Syndra

Envisioning a Sovereign

I legitimately thought I put this on my blog at some point, but evidently not. Some months ago I started a side project centered on updating Syndra's Lore and Voice Over, chiefly to correct the flaws I saw with her and build upon her strengths. An Art update is somewhat planned for, but as I'm still looking around for a suitable artist, that is much more out of my immediate control. You can find my public documents in their second draft iteration below. Third draft is currently being worked on; I'm largely happy with the Lore section, but the Voice Over may/will need a magnitude more work spent on it. It's worthwhile to point out that as I go on to describe this project, there will be a great intermixing of my views, ideas, and overall goals with the current existing canon. So, if you don't read it on Syndra's Champion biography, it's very likely that is something I've changed or influenced in some degree and not a Riot change.

Lore: Here

Voice Over: Here

Also, it helps if you read, or at least have the Lore section open, as the below is written from a design perspective rather than directly pointing to individual lines and the like.

Painting the picture of this project is a bit of a jumble as there are so many moving motivations involved with it. The core idea that would setup for the others, however, was my intense dissatisfaction with how much Syndra is portrayed in the fan community. For the vast majority of work you might see, Syndra herself was often portrayed as: crazy, insane, megalomaniacal power hungry, a girl-child in a woman's body, and various other de-empowering, dehumanizing, or outright demonizing characteristics. I do not mean exaggeration when I say it is hard to find any pieces that actually treat Syndra as a character and not a useless archetype.

My grievances with this problem rose to the point that some of my followers asked, 'Why not show us what you want, then?' and so, I did.

Small beginnings, greater endings

The immediate plan was to keep as much of her original personality intact as possible, but reshape it in a more humanizing way. Core principles I identified consisted of: extremely personally motivated, disregarding of 'oppressive' cultural norms, separated from the world with her unfathomable magic, haughtily arrogant yet not foolishly or idiotically so. As I worked on the story, I looked for ways to inject 'humanity' into the equation to make Syndra more a person than a Dungeons & Dragons sheet of features and personality quirks. Where does she begin to get where she is now?

One idea that arose above the others as the 'most relatable, with potential', was crafting Syndra as a peasant-born farmer. She has a few brothers, is the only daughter, and is the youngest child, and her entire family is mundane. No royal blood, no 'rulers in hiding', no ancient prophecies or godlike machinations. Thus, her birth, and the incredible magic she arrived to the world with, stunned everyone, and all of them her believed that she was some sort of great sign. This sky rocketed her family into prominence in her village when she was still less than a year old, and this great fortune would come to play a heavy burden on her throughout her traditional life.

Now, let's look at her homeland, Ionia. Built upon Asiatic principles, I often view the massive island continent with a vague feeling of pre-Imperial China. Capable, and with a mastery in some arts foreign even to the Valoran city-states, Ionia never really formed a strong central government. Their pacifist ways and pursuit of spiritual enlightenment motivated closer, more regional styles of governance where individual schools of thought may come to dominance. One of the few global ideals that would arise between all Ionians, however, was the pursuit of 'Balance'. In simple terms, a life in absolute harmony with the elements and world, with excess in either direction cut out. While it would be crude of me to say, you would find analog concepts in Buddhism and Taoism.

Where does this land Syndra in such a world? Undoubtedly while her magic would be seen as a gift, such cautious people would be quick to temper it however they could. The whole of their nation believes in Balance, and so Syndra would inherit that thinking like any other. She may even be harder on herself than others because she has that gift, and see it as a personal burden to bear. It would still be used, but always under scrutiny and scorn, on top of all the other normal womanly concerns that would befall her. After all, being a family's only daughter, and with such a prestigious tag attached, desirable suitors would do well to securing her family and herself for life.

And with this framework, we have our extraordinary-trying-to-be-ordinary Syndra, facing a childhood of profound dilemmas no one would eagerly embrace. All the while she's trying to keep a grip on things, the world around her is weighing heavier and heavier. Her magic is always growing, always finding new heights as an athlete training day-after-day would. In this, I make a very targeted and specific rule. Syndra's magic is powerful, but it is a part of her–it is not some thing, some other identity. She is seamless with it, and it is always in her control. At no point anywhere in her life does her magic not behave as she would want it to, even when in the deepest fits of rage, sorrow, or happiness. By implementing this rule, we establish that at no point is her personal agency ever in question. One does not get to make her a victim of herself just because she is 'all powerful'.

What's the powder keg for her? With her great power, and the weight of her culture upon her, it stands that something would push her to explode, even just once. And so, as she grew into young adulthood, and suitors came for her, the once wild and hardworking Syndra found herself being chased after. She didn't care for such things, for she is far too busy working and helping others, and most of her suitors fell off as a consequence. One particular man, however, simply never gave up, and one could imagine his pursuit turned into dogged chasing. Her family, elders, and what few 'friends' might even pressure her into accepting him, though she never would at all. Does she make the sacrifice for the greater good?

In a fresh design, this kind of 'chaos point', or period where anything could happen, is often subject to greater design concerns. In most of my small writings, I'm quite fond of using dice rolls to decide where any particular point goes from a list of possible outcomes. However, as we need to fit Syndra into her rebellious older self, this one is kind of determined already to have a 'bad time'.

She doesn't, and eventually his increasing pressure finally boils her stress over. I'm specific in mentioning that while the man doesn't die, he'll come out of the first 'offensive' use of her magic rather crippled for life. The event, and rejection of a 'normal marriage proposal', kicks off her village elders into a frenzy. They're all very afraid Syndra has finally done the unthinkable, has become too deviant or wild, or some other 'all consuming concern'. Through their own work, they find a tutor capable of teaching her magic 'properly', something that Syndra herself is quite glad to finally have.

This is another small, but critical detail, I strive to maintain. Syndra is a good woman–she wants to help her family, village, and lead a good life with the gift she has. The world around her, however, is constantly stabbing and needling at her every day. She's stressed in ways no one would want ontop of a full, 24/7-no-days-off workload. Thus, she's very glad to have a teacher who can help her become 'proper', at least in a way others might finally stop fearing/hating her so much. We are, at this point, still dealing with a normal person with an extraordinary gift. Those of you with any familiarity to the X-Men series may have an appreciation of what this angle entails.

With mixed feelings, Syndra leaves her small village life with her newfound tutor, and journeys to a monastery in the mountains. Here she learns, becoming quite educated in not only mundane arts and knowledge, but magical as well. She has her ups and downs, magic certainly comes easier to her with her innate relationship to it, though. Other teachers come and go, but for the most part it's almost exclusively Syndra and her one teacher, who I often call the 'Old Monk'. Over the years, they work and train together, and the raw peasant girl that was Syndra is shaped into a lady of considerable teaching and capability, all with that spitfire personality bubbling beneath the elegant restraint she learned. And yet, there was always this uneasy feeling with her, and as the years progressed, Syndra's health began to deteriorate.

Life is peachy and everything is going well, at least, as far as her duties are concerned. Yet, the start of what would catalyze Syndra into who she would become began on the very first day she arrived at the monastery. The truth would not come for many years, and that alone would drive the deepest dagger into her heart.

When her health hit its critical point, Syndra pressured her teacher into helping her. He would reveal to her that he had been siphoning her magic away for years, trying to keep it contained/under his control while she trained. This revelation utterly stuns Syndra, as he demonstrates in a simple conversation what years of (literal and emotional) agony have wrought on her. He never trusted her, despite saying so, and would go as far as invade her very person because he believed it right of him to do. An emotional battle of words follow with Syndra pleading her case, and the Old Monk never budging on his position. The end of the discussion comes with his ultimate threat: to strip the magic out of her completely, forever.

While the severity of 'magical severance' can be argued up and down, I often equate it to a sort of soul destroying experience. The body may be alive, but the person–particularly a mage–will never be wholly functional again, as so much of them will simply be 'gone'. Thus, such a threat might understandably be seen as a fate worse than death and characterize Syndra's horrific fear. Let's frame that, now. 'Hardworking, always trying to do what others say' Syndra is being told to bend the knee or get magical lobotomy done to her by the one person she came to trust the most. On top of years and years, almost her entire life in fact, of emotional and physical abuse and exhaustion. Nothing physical, mind you, she isn't beating beaten or tied up or anything, but the people around her are certainly fine with her working herself to death every day for no thanks. The Old Monk isn't some monstrous villain, at least as one might imagine a demon or other simple idea. His position will become clear in a little bit. Let's go on a joy ride, kids.

Unwilling to give in or let anyone else threaten her like that again, Syndra finally boils over completely, and she annihilates the Old Monk. In one fell stroke, she destroys the one person she trusted so much, all her faith in Ionia, all the dreams she had for her village and family–everything. She stands alone, apart from the world she grew up in, for the first time. Her health restores itself as her stolen magic returns, all but rejuvenating her to greater heights she would've obtained without the interference. With some thinking, and realizing she had nowhere else to go, Syndra draws upon her power and tears the entire monastery from the earth. The whole place, plus most of the mountain it was on, and lifts it right up into the sky.

This transition probably sounds a little sketchy or absurd, but it is a fun and strong detail for Syndra. If we frame her now floating fortress with the sort of mindset Ionians would have, she might even appear 'divine'. After all, how many people, save the Gods/Goddesses, could lift such a massive piece of land into the very Heavens? This'll play an important part later, but let's get back to the ride.

Furious and fraught with the pain of such betrayal, Syndra goes searching for answers. Pillaging her mentor's old study and hidden spots, she finds enough information to locate other monasteries. To her horror, they sound all too much like her own in their secretive, prison-like nature. She ventures forth, and over some years, investigates these monasteries, finding other people like her. While none of them came close to her in sheer power, they all possessed magical talent of some sort, and all their teachers kept them under invisible shackles. I leave it to others to decide what Syndra did to these teachers and the monasteries, but she ultimately ended up freeing many, many mages she ran across.

Here's an important part that helps characterize Syndra's behavior. She frees a lot of people, but notably doesn't free everyone. I often prefer to think of her finding people who are literally too dangerous to let out. Either because they are quite dangerous, as a person, or their magic is so unstable/problematic that the prison is the only way they can survive. This distinction builds a very potent gray morality, as it indicates Syndra can agree with the imprisoning reasons some of the time, but not all of the time. Consequentially, this also establishes the Old Monk as a sort of 'jail warden', responsible for keeping dangerous magic users under control. How or why is a point of intrigue that will drive her story later on, but the Old Monk did not make his magical severance threats because he himself was malicious. He was simply doing his job.

The Sovereign of Ionia