#like did we have to implicitly call the nature of my marriage into question about it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'you're platonically married and you write about platonic sex, how can you possibly care about the distinction between platonic and romantic, what's the point, isn't that silly' is a late but strong contender for most mystifying and vaguely hurtful thing someone has said to me in 2024

#gav gab#like i really dont know what to do with this one lmao#like did we have to implicitly call the nature of my marriage into question about it#dont care for that!#'oh you're married? well NOW what's the point in differentiating at ALL'#i- pardon me?#fascinated with this being the breaking point#like i guess i'd have been allowed to care about platonic relationships#and SPECIFICALLY AND EXPLICITLY PLATONIC relationships if i. hadn't gotten married?#if i didn't write about friends fucking?#wha'ts the implication here#no go on please tell me. WITHOUT implying it's impossible to enjoy physical or emotional intimacy#above a certain threshold without romance#or else the point of even having the concepts of romantic and platonic are meaningless#i feel like id be more offended/hurt by that whole thing if i could like#even understand it lmao

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Having established friendship’s intimate links to proper womanhood, and having demarcated the unrequited passions, obsessive infatuations, and conjugal relationships often conflated with friendship, we can now turn to female friendship itself. What repertory of gestures, emotions, and actions defined friendship? How did women mark their friendships and how did friendships evolve? How did friendship interact with kinship and marital bonds, religious belief, and the Victorian gender system?

One of the most striking differences between Victorian and twentieth century friendship is how often Victorian friends used “love” interchangeably with weaker expressions, such as “fond of” or “like,” and how often women used the language of physical attraction to describe their feelings for women whom a larger context shows were friends, not lovers. In 1864, when Lady Knightley’s beloved cousin Edith died, the twenty three-year-old offset her grief with a romantic quotation: “And yet through all I feel sure / ‘Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all’” (71). A year later, Knightley rhapsodized that a new woman, also named Edith, “has come to bless my life. . . . I have grown to love Edie very dearly” (105–6).

…Lifewriting provides many instances of a woman recording her attraction to other women or boasting of being “intimate” with other women in youth and adulthood; Ann Gilbert recalled how as a girl, her sister became “by instantaneous attraction” another girl’s “bosom friend” (24, 78). In an 1881 memoir published in 1930, fifty-one-year old Augusta Becher recalled a youthful meeting with a young woman who “proved just charming—took me captive quite at once” and went to dinner wearing “lilies of the valley I had gathered for her in her hair” (37–38). Ethel Smyth’s autobiography discussed her own sexual affairs with women in coded terms but openly described how her mother and the children’s author Juliana Ewing “were attracted to each other at once and eventually became great friends” (68, 111).

Others wrote of loving (rather than liking) women; in 1837, Emily Shore (1819–1839) wrote of her friend Matilda Warren, “I love her more and more. . . . It is difficult to stop my pen when once I begin to write of her.” The two women argued fine points of religious doctrine but concluded “that, after all, we agreed in loving each other very dearly.” Addressing her friend Catherine Marsh in 1862, twenty years after they first met, a married woman wrote, “My Katie, you were mine in 1842, and you have been twenty times more mine every year since,” reveling in friendship as the proud possession of a beloved intimate (40).

Such expressions of love between friends, as we have seen, were perceived as fulfilling the social function of feminization that led Sarah Ellis to promote friendship alongside motherhood and marriage as one of the duties of women. In The Bonds of Womanhood, historian Nancy Cott influentially argues that in the United States, domestic ideology promoted friendship between women as one way of confining women to a female world and to female roles, even as female friendship also laid the foundations for a feminist movement that sought to open the male worlds of education and professional work to women.

But even women who were not active feminist reformers enjoyed the ways that friendships allowed them to go beyond the limits assigned to their gender without being perceived as mannish or unladylike. Friendship was both a technology of gender and an enactment of the play in the gender system. As friends, for example, women were able to exercise a prerogative otherwise associated with men: taking an active stance towards the object of their affections. In an 1880s memoir about the 1830s, Georgiana Sitwell, later Swinton (1823–1900), recalled a governess who “was romantic, worshipped the curate, and formed a passionate attachment to our newly imported French governess.”

…Counseled to be passive in relation to men, women were allowed to act with initiative and spontaneity toward female friends, and friendship enabled women to exercise powers of choice and expression that they could not display in relation to parents or prospective husbands. Bonds with parents and siblings were given, not chosen, and friendship was for many girls their first experience of an affinity elected rather than assigned. For women who grew up in families with over ten children, friendship was also a girl’s first experience of a dyad rather than a swarm.

While women had the power to turn down marriage offers and had subtle ways of attracting men they wanted as spouses, they were not allowed to choose a mate too overtly; only in Punch lampoons did women propose to men, and it was considered equally improper for women openly to initiate courtship. It was perfectly acceptable, however, for a woman to make the first move toward friendship with another woman, or to solidify amity by writing to a female acquaintance, calling on her, or giving her a gift. Aristocratic women had exchanged gifts, miniatures, and poems for centuries, and in the Victorian era the practice became widespread among middle-class women of all ages.

One of adolescent Emily Shore’s several intimates, Elizabeth, gave her a “chain made of her beautiful rich brown hair” before leaving England, which Shore considered a token of her friend’s affection and looked forward to displaying as a sign of social distinction: “I have generally worn a pretty little chain of bought hair, and when people have asked me ‘whose hair is that?’ I have been mortified at being obliged to answer ‘Nobody’s.’ Now, when asked the same question, I shall be able to say it is the hair of my best and dearest friend” (269).

Mature women painted portraits of friends and composed poems about them that they then bestowed as gifts, creating a friendship economy based on artifacts whose praise of a friend’s beauty, loyalty, and achievements also implicitly lauded their maker for having chosen so wisely. Female friendship allowed middle-class women to enjoy another privilege that scholars have assumed only men could indulge—the opportunity to display affection and experience pleasurable physical contact outside marriage without any loss of respectability.

Women who were friends, not lovers, wrote openly of exchanging kisses and caresses in documents that their spouses and relatives read without comment. Women regularly kissed each other on the lips, a gesture that could be a routine social greeting or provide intense enjoyment. Emily Shore, whose Bedfordshire Anglican family was so proper they did not allow her to read Byron, described in a diary later published by her sisters the “heartfelt pleasure” she obtained from a visit to her friend Miss Warren’s room: “She was sitting up in bed, looking so sweet and lovely that I could not take my eyes off her. . . . She made me sit on her bed, and kissed me many times, and was kinder to me than ever [and] held my hand clasped in hers” (203).

Female amity gave married and unmarried women the opportunity to play the social field with impunity, since a woman could show devoted love, lighthearted affection, fleeting attraction, and ardent physical appreciation for multiple female friends without incurring rebuke. The editor of Emily Shore’s journals noted that when Shore wrote of loving Matilda Warren her diary was also “filled most especially with her passionate love” for a woman named Mary (207). Thomas Carlyle wrote indulgently about Geraldine Jewsbury’s affection for his wife Jane as well as about “a very pretty . . . specimen of the London maiden of the middle classes” who “felt quite captivated with my Jane.”

Marion Bradley, wife and mother, wrote of her deep bond with Emily Tennyson and in an 1865 diary entry observed more casually that her new governess was “a gentle, lively, wise, cultivated little creature. . . . I love her and hope always to be very thoughtful for her and good to her.” Equal latitude was afforded to unmarried women. The biography of Agnes Jones (1832–1868), written by her sister and published in 1871, narrated her life in terms of two arcs: achievements as a nurse and love for various women. In adolescence, her sister’s “ardent affectionate nature was drawn out in warmest love” for a teacher, followed by an “attachment” to a fellow missionary that “ripened into a warm and lasting friendship” as well as a close connection with another “devoted friend” (15, 21).

In an era that saw no contest between what we now call heterosexual and homosexual desire, neither men nor women saw anything disruptive about amorous badinage between women, and therefore no effort was made to contain and denigrate female homoeroticism as an immature stage to be overcome. Only in the late 1930s, after fear of female inverts had become widespread, did women’s lifewritings start to describe female friendship as a developmental phase to be effaced by marriage. Since then, erotic playfulness between women has either been overinterpreted as having the same seriousness as sexual acts or underinterpreted and trivialized as a phase significant only as training for heterosexual courtship.

…Victorian society harshly condemned adultery, castigated female heterosexual agency as unladylike, and considered it improper for women to compete with men intellectually, professionally, or physically. But a woman could enjoy, without guilt, the pleasures of toying with another woman’s affections or vying with other women for precedence as a friend. In maturity as in youth, women delighted in attracting and securing female friends whom they often singled out for being beautiful and socially in demand. In a letter to her brother in 1817, the unmarried Catherine Hutton of Birmingham (1756–1846) boasted, “I have been a great favourite with a most elegant and clever woman.”

To a married female friend who often gave her fashion advice she wrote of acquiring yet another “new” friend: “[S]he is beautiful, unaffected, and to me most friendly.” Female rivalry over men was discouraged because it implied that women fought for and won their husbands, but women were allowed the agency of competing for one another’s favor. Lady Monkswell crowed about having “supplanted” one woman as the “great friend” of Mrs. Edith Bland, and the relative who edited her published letters and diaries included many other instances in which she bragged of similar successes (12).

Such relish in contending with women over women was possible without any loss of ascribed femininity, even as it took women well beyond the parameters of womanhood as defined relative to men. Just as women boasted of making conquests of female friends, they also openly appreciated each other’s physical charms. Women commented compulsively in their journals and letters on the appearance of every new woman they met, even when they did not know the woman personally.

Adrienne Rich has influentially argued that “compulsory heterosexuality” works by stifling all kinds of bonds between women, from the homosocial to the homosexual, but Victorian society’s investment in heterosexuality went hand-in-hand with what we could call compulsory homosociability and homoeroticism for women. The imperative to please men required women to scrutinize other women’s dress and appearance in order to improve their own, and at the same time promoted a specifically feminine appetite for attractive friends and lovely strangers. Conduct literature praised female friendships for developing in women the loyalty, selflessness, empathy, and self-effacement that they were required to exercise in relation to men.

Women’s lifewriting shows an acceptance of that idealized and ideological version of female friendship; few women left records of conflict or rivalry with friends, though some acknowledged engaging in jealous competition with relative strangers over prized acquaintances and intimates. At the same time, friendship provided a realm where women exercised an authority, agency, willfulness, and caprice for which they would have been censured in the universe of male-female relations. Female friendship provided women with a sanctioned realm of erotic choice, agency, and indulgence, in contrast to the sharp restrictions that middle-class gender codes placed on female flirtation with men.

A woman who wrote of spending time alone with a man in his bedroom or giving him a lock of hair without being engaged to him would have transgressed the rules governing heterosexual gender, but to write of doing so with another woman was to describe an accepted means of forming social bonds and acquiring social status in the realm of homosocial gender. The celebration of women’s friendships shows that femininity was defined not only in relation to masculinity but also through bonds between women that did not simply tether them to the gender system but also afforded them a degree of play within it.”

- Sharon Marcus, “The Play of the System.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1823 Aug., Tues. 5

7

11

In the stable etc. 1/2 hour – Read from page 71 to 83 on “the letters and life of Ninon de l’Enclos” volume 8 (No. [numero] 15) Retrospective Review – I agree with the reviewer – some fastidious readers may possibly object to the publication of such an article thro’ such a medium –

Dissatisfied with several passages of the letter I wrote last night to M– [Mariana]. Wrote it over again in 3/4 hour in a hand so much less close, that in spite of the great deal left out, made it fill 3 pages and a few lines of crossing on the 2nd page – There seemed some appearance of annoyance and displeasure in my 1st letter which I entirely avoided in my 2nd –

Went down to breakfast at 9 40/60 – At 11 took George in the gig and set off to Haugh – Put a letter into the post for my uncle, and got to Haughend in 50 minutes – All the party at home with the addition of “Captain” Butler, a very grood sort of, vulgar, quondam Captain of an Indiaman – The young people did not appear till luncheon –

Sir John A– [Astley] franked my letters to Mrs. N[orcliffe] (Langton hall, Malton) to Miss Marsh (Micklegate York) and to M– [Mariana] (Lawton hall, Lawton, Cheshire) and they went in the Haughend letter bag in time for yesterday’s post – Nothing particular in the conversation way –

Sir John somehow or other inquired if I believed all Homer’s stories, or that there ever was such a place as Troy, or such a siege – I saw he had read Bryton or some sceptic on the subject and was very gentle in what I said in support of my historical creed – At last Sir John (after some flimsy observation) tried to shew that women were as much respected in ancient days as now – Briseis as much respected by Achilles, as wives were respected by their husbands now – Woman as well treated then as now – He (Sir John) would have treated lady A– [Astley] as well at that time as he does at this – I did not say much, not wishing to appear to have too much the better of the question argument for none said a word about it but ourselves, and Sir John is evidently looked up to as an oracle by them all, tho’ his responses will never set the Thames on fire by their wisdom –

He complimented his wife exceedingly – In fact, she is pretty enough, stylish enough, sensible enough, everything enough for him – Speaking of their place of family, she observed she “always thought the Astleys were an envied family in Wiltshire” “My dear” said he “they envy me for having got you” –

It is plain enough to me from their manners etc. etc. that they not exactly comme il faut with the Wiltshire county society – They have had the house in London that Sir Jacob Astley and his family had had, and many calls were therefore made upon them by mistake – They returned some – Were admitted at one house, the manners of the ladies shewed they were not expected, and the A– [Astley]s took their leave – A party was soon afterwards given by the family, and they (the A– [Astley]s) were not asked – They do not get on in London society – Nor as yet perhaps are they likely to do – Nor will Miss A– [Astley] even after “she has been presented” (at court) –

Lady A– [Astley] has not worldly nous enough to keep all these things to herself – Thinks Mrs. William Henry Rawson very ladylike, Ditto Mr. Christopher Rawson – The manners of the Society here suit the A– [Astley]s very well – Captain Butler it seems has had 1 or 2 premiums from the Doncaster society (I know nothing of this society) for feeding horses – Kept his draft-horses throughout the winter at 3/5 a head on chopt straw and line-seed – His saddle horses only cost him about 5/. [shillings] a week having nearly the same as the cart-horse with the addition of a little hay and corn –

Boils down the linseed to the consistence of cream – Perhaps about 2 quarts water to a pint of lineseed – Mixes this with their oats or chopt straw to a proper (a mashy?) consistence, and gives them as much as they will eat – A chopping machine at Doncaster 7 1/2 guineas – Try our horses with about 2 wine-glasses full of linseed at first – Merely pour on boiling water – and let the seed stand till it is mucilaginous –

This plan is good for feeding cattle – It is the way in which dealers fatten up horses – But it wont do for hunters, or horses from which speed is required – The linseed works away to greasy perspiration – Runs out of the anals like melted fat – They must have good hay and corn for speed – But cart-horses do uncommonly well on this food –

They all like Caradoc – Think him “a very likely horse” – His toes turn in a little: this is best for a gig-horse – If the toes turn at all outwards, the gig horse can scarcely ever keep his feet – He cannot hold up up hill and down –

Staid till about 3 – Called at Saville hill to ask Miss P– [Pickford] whether, when she called with me at Haughend, she meant to call on lady A– [Astley] or not – Not – Asked her to come to Shibden to see Caradoc’s long switch tail cut – She would meet me at the library in 1/2 hour –

At 4 1/4 – drove thro’ the town, past Northgate, and Crosshills, and turned up by Greenhill, stopt at Furnish’s, and got a pair of new reins 10/6 – Left George to drive the gig home from Northgate, and without going into the house, went to the library – Shewed Miss P– [Pickford] the article respecting Ninon de l’Enclos (vide the 1st line of today) and the points of Humour (vide page 79) – She agreed with the retrospective reviewers, and with me that the soldier and his chére amie was the best print –

She walked home with me to the top of our little lane, but must there return for the children who would come to meet her – We walked about on the top of the bank – My aunt joined us – She left us in about 20 minutes (at 6) –

We then walked to H–x [Halifax] – Miss P– [Pickford] returned with me up the old bank even to xxxxxx. I walked back again with her a little way up the Cunnery lane, when we met her party of children – 3 Wilcocks, 2 Paleys, and Miss Jones the governess, and we parted –

Our chief conversation about Miss Threlfall and my entreaties to see her last letter. Nothing could prevail till at last I asked if she feared its telling me anything I did not know before. On finding this the case, I said I would soon sooner move this fear by proving that I was not as still suspected in any degree of uncertainty.

I wondered she did not know this already, but I had wrapped up my meaning too much and she should now have it so clearly that no doubt could possibly remain in her mind. Upon this I said I considered her connection with her friend a marriage of souls and something more. That if they were on a visit and their friend provided them separate rooms it would be unnecessary and they would presently defeat this arrangement by being together.

Under other circumstances it would have been a wonder that with beauty fortune etc. etc. Miss Threlfall did not marry but now it was no wonder at all. Asked Miss P[ickford] if she now understood me thoroughly. She said yes. I said any would censure unqualifiedly but I did not. If it had been done from books and not from nature, the thing would have been different. Or if there had been any inconsistency first on one side of the question, then the other. But as it was, nature was the guide, and I had nothing to say there was no parallel between a case like this and the sixth satire of Juvenal. The one was artificial and inconsistent the other was the effect of nature and always consistent with itself.

At all events, said I, ‘you remember an early chapter of genesis and it is infinitely better than the thing alluded to there,’ meaning onanism. ‘This is surely comparatively unpardonable. There is no mutual affection to excuse it’. Miss P[ickford] did not say much but seemed satisfied.

‘Now,’ said I, ‘the difference between you and me is mine is theory. Yours practice. I am taught by books, you by nature. I am very warm in friendship, perhaps few or none. Moreso, my manners might mislead you, but but I do not in reality go beyond the utmost verge of friendship. Here my feelings stop. If they did not, you see from my whole manner and sentiments I should not care to own it. Now do you believe me?’ ‘Yes,’ said she, ‘I do.’

‘Alas,’ thought I to myself, ‘you are at last deceived completely.’ My conscience almost smote me but I thought of π [Mariana]. It is for her sake that I fisrt [first] thought of being, and that I am so deceitful to poor Pic, who trusts me so implicitly and at last turned no objection to my seeing the letter. I said perhaps there was not another in the world she could trust so safely. Perhaps not Miss Caroline Renouard, she was not read or liberal enough tto [to] think as I did. She would condemn unqualifiedly. Pick agreed.

I owned my manners might mislead people, particularly before I knew as much as I do now, before I read Lubinus’s Juvenal, before I first knew Miss Brown of whom she has heard reports. But now I knew how to be more careful. Yet still, my manners might mislead Miss Vrelfall [Threlfall]. She said, ‘yes they would’ –

I ended by saying I was now satisfied that she thoroughly understood me and that I had had an opportunity of telling her my sentiments, for she must often have wondered and not known what to make of me. We parted mutually satisfied, I musing on what had passed. I am now let into her secret and she forever barred from mine – Are there more Miss Pickfords in the world than I have before thought of –

Came in to dinner a little before 7 – Had ordered George to have the gig ready a little before 9 in the morning to go to Huddersfield to speak to Pontey about coming over to plan our new road to the house, etc. – But finding my uncle against it contrary to my expectation – (I had always thought all he said against it in joke) – I immediately countermanded the order very quietly determining never to mention the thing again – Nor to mention planting or otherwise improving the place –

I told my uncle very quietly I certainly would not teaze him any more on the subject; and I shall indeed change my mind, if I do – The thing absolutely did not annoy me at all – I immediately thought to myself, ‘perhaps it is best as it is – I incur no responsibility – etc. etc.’ Perhaps I may save my money in future instead of laying it out on the place and leave things as they are –

Barometer 1 3/4 degrees below changeable Fahrenheit 56º at 9 p.m. – Rainy morning till between 10 & 11, afterwards a shower or 2 which I escaped and otherwise a toleraby fine day i.e. fine afternoon and evening – Came upstairs at 10 25/60. E [two dots, treating venereal complaint] O [three dots, signifying much discharge] Missed washing just before dinner –

Miss Pickford called this morning and sat a little while with my aunt – She brought me Samouelle’s system of Entomology to read –

[sideways in margin] Major P– [Priestley], speaking of horses that went near the ground, called daisy-croppers – i.e. going so near the ground as to crop or strike off the tops of the daisies – Drove along the new road today for the 1st time

“the soldier and his chére amire“– Points of humour; illustrated by the designs of George Cruikshank [x]

1 note

·

View note

Text

(found this while looking for something else. I can only assume it’s related to my big ethics essay considering what’s at the bottom, but even my digital file keeping is akin to post-it notes and scatted pieces of paper.)

"If the Empire is to have my life, why can't I have a say in how long they should have it? If I can decide what to do within it, why not outside it?" Rochester looked uneasily to Simone. She stared back at him, placid as a river sheathed in ice.

"If you get that," she said after a while. "Why can't I get that?"

"You should. I should. We paid our dues." Maybe everyone has.

For (contrived purpose) Wilhelm, Rochester and Qiu find themselves on a planet recently instituted with new leadership Imperial. In disguise they are not Imperial citizens and are treated harshly by the enforcement officers. Rochester area this as an injustice to the empire as he knows it: a corruption of the ideal of progress under Imperial leadership, the use of sith ideology outside of context. Wilhelm, being off a lower class, sees it as rote. There is a brief discussion on the ship about relationships: the expectation of Rochester to have had the marriage with Stion'n (or some other appropriate woman) before the intervention of Sith, Qiu remarks she gave eggs to the eugenics programme and Willem points out he "failed" an exam on 97/100 and did not get invited to the programme despite surpassing colleagues in areas untested. As they prepare to leave Rochester involves himself in a riot against the planetary governor, believing that they will be replaced for their failings. It's some weeks later, on another planet, he learns of the retribution meted out against the populace, and sees the extent of the propaganda used.

"If there's no reward or punishment for unjust acts and likewise for just, or that for this moment we not consider them and think only of the act themselves, why act justly? Or unjustly?"

"Nothing?"

"Nothing at all."

Rochester shrugged. "I can't think of anything."

"So nothing in the act itself is preventing you?"

"You said no external factors. Aren't my own feelings external factors to the act?"

"So the justness or unjustness of an act is not in the act itself?"

"I don't know. Is a human life different to a leaf, if we don't consider consequences?"

"A 'human' life?"

"Sorry, a person's."

"And we consider consequences?"

"Aren't those the external factors? I wouldn't be rewarded for saving a murderer from drowning but rather punished for it?"

"Is a person's life not inherently worth something?"

"Beyond their being a murderer?"

"I think we might be getting off track."

"Well, if you remove consequences of the action, doesn't the action then become amoral?"

"How so?"

"There's no question of justice when I wave my hand, but if I strike someone with it, then the question arises. But if there's no consequence to myself or the person I hit, where's the need to question its justice or morality?"

"So, you think the justness of an action might stem from it taking place in a system of consequences and reactions?"

"I suppose so." A little uneasy. Unsure of his answers and thoughts for the road ahead was unpaved and long, and shrouded in ignorance.

It is, in the Imperial culture, just that the Sith might rule as they do for they are favoured, might is within their nature and the weakness self correcting in their system.

It is to be above one's station if, being not force sensitive, one attempts to exercise that rule of might.

The empire as a tool of sith has the might to be right, but its citizens within must act appropriately. As all citizens are equal, they are to act equally to each other (but they aren't equal, class and breeding are paramount, where it is merit one might advance but first merit is birth). To act as a sith is to put oneself on their footing, and thereby in their court. So that all citizens are equally protected from the Sith court, no citizen must enter it.

Under the sphere of philosophy comes the ministry of education which, in its entirety, covers education from childhood to adulthood, propaganda and censorship. Censorship in part extends the role of sith who search for heretics by ensuring that texts published to have anti-Imperial sentiment. This might include, but is not limited to, characters engaging in un-virtuous or sinful acts who do not get their comeuppance (see Hayes code) or who are otherwise depicted sympathetically, expect where they are sith and act in a sith manner (that is virtuous to a sith but not a citizen). Less so on core worlds but common on those conquered is the existence of illegal printing presses (sometimes actually paper and ink) that create anti-Imperial leaflets alongside unapproved works or uncensored versions of sort after works. Even though romance is a common genre in the empire and many books are sold cross borders, the Cabinet censors parts or rewrites whole chapters to better suit "Imperial tastes".

Virtues of the Empire:

Loyalty

Of the citizen:

Honesty

Integrity

"Strength of will"/perseverance

Charity to children

Courage

Pride (in the empire and ones achievements)

Wisdom

Temperance of action and feeling (self discipline)

Orderliness *at once keeping stuff in order, but also understanding one's place in the empire

Will to excellence *the best me and the best I can do makes the empire better as a whole or the the best I can do for the empire is the best me

cleanliness *don't smell

Unity *not necessarily friendliness, but not rocking the boat as it were

"In all ones actions and duties to uphold the standards of the Empire"

Timely - to know when best to be serious and to be jovial. Also, be on fucking time

Respectfulness

Of the Sith:

Cunning

Wisdom

To live one's truth (the existential ideal)

Strength

Will to power

Justice (upholding Imperial laws and ideals)

Magnificence

The Sith might also be expected to perform the virtues of the citizens listed above, particularly those of being timely, orderly and clean. When in the presence of Sith of higher standing, or of citizens of high standing particularly those of the military or intelligence, then such actions will also be expected.

Temperance (self discipline) - the Sith rule and control their emotions. Though one might become powerful through unbridled rage, one might lose oneself to it and lose one's mental faculties including (ironically) the _will_ to power, making one un-Sith-like.

As ever, these virtues are not to be practiced in excess nor be shied from. Life in the Empire is a balancing act.

The Empire contains three formal classes, four if slaves are considered.

There are the Citizens, which one could class all as for they all live within the Empire, but Citizens are those who are born to Imperial families, typically within core Imperial worlds. They have the force of longevity behind them, their presence and purpose within the Empire is inherent. They have the tried and true Imperial education, in mathematics, warfare, literature and the sciences. They all hold in some form a military position. A teacher can be called upon to fire a gun, as a baker can be expected to fix a tank. Full time military service is performed by all citizens for four years, and after that either continue within the military system or return to perform other vital roles within the Empire.

De facto citizens or the Treatise'd. Those living in planets the Empire has conquered, by war or through the Treaty of Coruscant. Formal expectations of them are the same, however Citizens oft treat them, not necessarily with contempt but not with high expectations. Citizens see their lack of Imperial education (something being rectified but sorely lacking in the adult generations) as a fault that prevents them from performing the best they can for the Empire (see the virtues). This disregard for their own experiences, talents and cultures does, to put it mildly, chafe the De Facto citizens.

The Sith. They can learn philosophy. It's not the most popular subject, but many who do involve themselves in the Ministry of Education, and by extension the Bureau of Propaganda and the censorship cabinet. Philosophy is a poor subject for citizens, as it gives one the ability to ask questions and not necessarily accept the answers given.

Rule consequentialism (not utility as this implies Bentham et al, but "to the betterment of the Empire" that is, does this action benefit the Empire, how so, to what extent) and virtue, as outlined. As the legal system must exist for the society to function there are of course pre-existing rules.

For an example from the game, murder. It is implicitly stated that murder is _not_ allowed (the quest of the acolyte sith ganking civs) through much of the society, up to the Dark Council, where it seems to be a matter of not getting caught (a virtue of the Sith is therefore cunning; Darth Thanaton's adherence to tradition in the face of the easier route is seen as an eccentricity ultimately turned weakness).

Education in the Sith language starts at an early age. For those who are sith born to sith, it is a natural process of learning as with any mother tongue. For those who have force abilities at a young age, or are believed to be likely of showing them, this is a more formal education one might expect on a school setting, starting also at a young age. Obviously this approach favours those who have the opportunity to learn and whose abilities can be either reasonably expected it recognised. Those who come into their abilities late, or come from de facto worlds, or even are slaves, may never receive this education. The ability to speak the sith language is a merit. This is how merits play out in the Empire, and how their meritocracy works. Birth is a merit, opportunity and privilege also.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobuyuki thought(s) that i had

fyi Buyan = No[Bu]yuki + [yan]dere ; as Nobu & Yuki are shorthands already in use

This isn’t so much of an attempt to explain or Rationalize of Buyan’s means of expressing his yandere - it’s really more like a thought or consideration on things tying TO it and potentially something that, were I to write fanfic from his POV or angled around him as a character, I might...include or note upon at an appropriate point.

Note: screenshots that are not mine will be sourced, otherwise all screenshots ARE in fact mine.

SO.

Buyan is the Sanada clan heir. He is utterly devoted to his clan and his duties as heir - that has never been in question; he is responsible, he is trusted implicitly (by the Sanada and from the looks of it, by those in Ueda/at least the city (town?)) around the castle, and honestly, he’s adored - again by his clan and the others mentioned. Saizo is an exception insofar as adoration/etc, but he does seem to trust in the fact (at least) that Nobuyuki IS wholly dedicated to the Sanada and the clan’s well-being/future/etc.

I do not know how much background is given in other Sanada-related LI routes, but for certain in Buyan’s, it goes into his history/growing up, etc.

At least...partially, as Buyan himself only reveals so much - some of those details, imo, are important! But ever the mysterious angel-faced manipulator, he almost always smoothly glides the conversation back to MC herself. Leaving MC up to learning from everyone around her + Buyan to inform her and fill her in - even Masayuki himself!

But the overall gist is that Nobuyuki’s life is not his own. His life is for the Sanada, he must live for them - both figuratively AND literally. It’s part of the final confrontation in his route - he must live, no matter the cost, as he is the one who will ensure the Sanada’s survival (and potential rebuilding and/or expansion, even) regardless of what happens to Yukimura and Masayuki.

As such, his life is planned out more or less from the beginning. Now, due to his temperament (likely how he’s been raised helps too, I’m sure, but his temperament is DEFINITELY suited to his role as clan heir), he has accepted this - his role, his duties, his Purpose...there’s no plot point in his route for him trying to shuck the role nor does MC try to convince him to live for himself, etc.

Again, being clan heir suits him - he is a natural charmer, manipulation requires some practice but he’s clearly already a Master, as well as a tactician and, well, he’s fucking smart. No if and or buts about it.

The closest to anything approaching a negative is the weight of having to stay behind, unknowing of his brother, his father - the people important to him - until he gets news of them/they arrive home. And that IS hard. Yukimura is a brilliant warrior but he’s not invincible and he is the Warrior between the two of them. Buyan can clearly hold his own in a fight, he’s still a samurai after all, but again. Heir, not the Warrior.

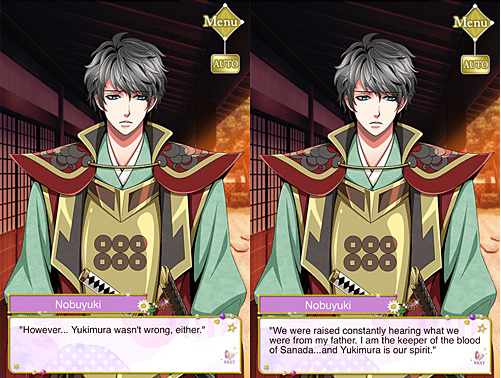

Which, again, is said a number of times in his route & I wouldn’t doubt more than once in Yukkins’s own route, take just this scene for example:

SOURCE

All of this rambling leads me to my main thought regarding his behavior towards MC in his route/previous ES/etc featuring him + MC; Nobuyuki’s life, purpose, existence...is the Sanada clan’s. His childhood wasn’t even his because after his & Yuki’s mother died, atop being heir, he more or less took over raising + tending to Yukimura as well (and in his subtle ways, continues to do so SOBS).

And just as his life is his clan’s, the clan has placed the entirety of their trust in his hands (not simply bc he is heir, he is a DAMN sharp man and brilliant politician, truly) and his decisions, thus, are taken more or less at face value. And because of this trust placed in him, his father has thus allowed Buyan to actually choose his own wife, rather than numerous attempts at arranging marriages/etc.

Very impressive indeed.

It is a duty, of course, but one that Masayuki (and the clan) trust him to fill & trusts in his choice of a bride with essentially little to no questioning. Even as Masayuki knows about his son’s...occasional “eccentric behavior” and his strict list of necessary Sanada Bride qualifications. Buyan is, apparently, allowed to be as picky as he chooses.

Regardless of his son’s eccentricities, I have little reason to doubt that Masayuki has been one if the biggest (as Nobuyuki was older than Yukimura when their mother died, so she would have had time to influence/leave impressions on him herself) factors in Nobuyuki’s education, in all his duties as heir, not to mention implementing values upon Buyan - especially IN regards to marriage and finding a wife.

This brings up questions that I have little time for, as analyzing Masayuki is not the point of this post.

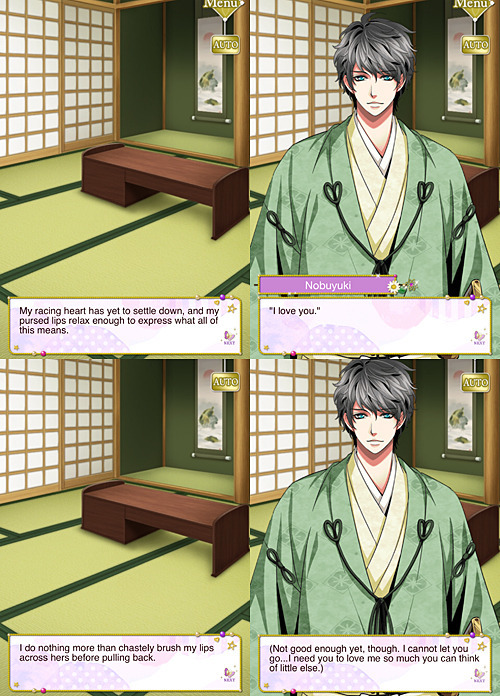

Instead, I would like to point out this particular piece of advice from Nobuyuki’s route and how it rings true to me in regards to his relationship with MC, regardless of his dangerously subtle yandere mentality:

Nobuyuki wants to know everything there is about MC. As suited to his subtle yandere ways, he will manipulate her and ensure that she comes to him to more or less reaffirm (to him, in his mind) that she does, in fact, want him. And that she loves him.

He doesn’t not force or coerce these affirmations (I call these as such bc yandere-types frequently tend to need Affirmations from their Beloved to appease their obsession/possessiveness/insecurities/etc etc etc and while not blatant in this way, Buyan does seem to have at least a Smidge - even if it’s mostly for his), but instead sets up a strategic stage (arguably something of a game) that instead ensures MC comes to him herself and As demonstrated in his thoughts from his Draughts of Starlight ES:

Source

Of course, there’ve been times where Buyan is caught off guard by things MC does, be it unexpected demonstrations of kindness/affection, making him his favorite dessert without her even knowing it is his favorite, her resilience & matching his own force of will when directly confronting him, etc etc etc.

His reactions tend towards being surprised and then shifting to fascination and either amusement & often at least a level of curiosity OR as we do get to see, strong urges of affection. And when he shows that affection, boy, it is like unleashing a tidal wave. His feelings are next level Intense and his expression of them is no different.

Holy fuck, this is probably just vague tangents vaguely related to the entire reason I started this post in the first place at this point. Let’s get TO what I could have said in fewer words.

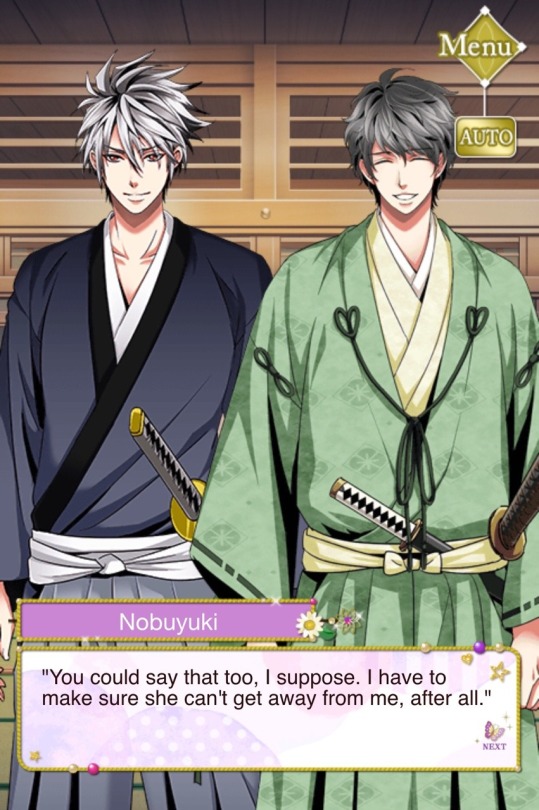

THOUGH, a quick addendum - regardless of his choice in wife, since whoever he chooses as his wife will meet those requirements of his (some exceptions, like noble lineage, are excused like in the Draughts ES because MC is Perfect in Every Way otherwise, and I assume the same goes for MC in his own route), she will thus be ideal and him, being the gentle yandere he is, would not want to let her go. Or for her to escape. The classic most example in Yukimura’s...route? (I’m fairly sure this is) in response to Saizo calling [Nobuyuki] his [future] wife’s [prison] Warden:

Source

God, I love your beautiful face and fluffy hair, Buyan.

Ahem, anyways.

ALL of these various...points...I’ve touched upon, IN MY OPINION, all point to a likely...thought process? behind Buyan’s attitude towards his MC. The MC, his bride...

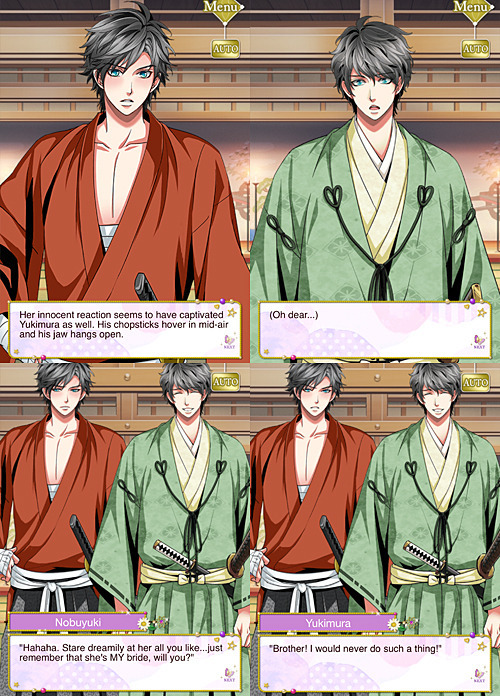

And it is in your best interest to NOT forget that she is his. Even you, Yukkins, cannot afford to pose a threat to your beloved brother in this regard:

Source

His, as Nobuyuki is keen to remind, [future] wife...

A person who was to fulfill yet another duty of his to his clan, a theoretical woman that was - regardless of even being his ideal bride - ultimately, intrinsically, merely part of one of the numerous obligations that were expected of him as heir...Well, back to his ES again (I had more screenshots myself to use as well but I spilled coffee on my laptop and now it’s drying SOB) to let Buyan say it himself:

Source

...turns out to be what/who he regards as The Greatest Blessing of his life.

And not just randomly or by chance either. HE chose her himself, for himself, of his own volition. Somehow, within the contract - as he refers to it - of his life, one of the few things he could, in fact, choose for himself...brings him utter satisfaction. He’s not pleased, he feels blessed by this choice he made - taking a chance with a young woman who captured his fascination and hit essentially all his switches. Risky? Certainly.

But a risk he was willing to take and the payoff was more than even this angel-faced mastermind could have anticipated.

This boils down to, essentially, the fucking thought I had in the first place in regards to some contemplative insight into Buyan’s POV/Buyan focused perspective regarding his route’s MC. Let’s do a quick summary:

Nobuyuki is the clan heir, he was born into it, bound by the obligation, and was settled into his role very neatly.

Nobuyuki is allowed to make decisions for the Sanada as he is trusted by his clan & family.

Nobuyuki is trusted with these decisions and has the clan’s trust because he has obviously proven over the years, after getting involved in the duties as clan heir and future clan head, that his choices are those that will most benefit the clan.

Nobuyuki’s choices will always most benefit the clan, they must, and so while he has access to a wide variety of means to accomplish what must be done and he is allowed to make any choice (often without any explanation of what he did, or why he did, required of him), he ultimately is bound by the duty + obligation that whichever choice he makes, it is always for the clan’s greatest benefit.

Thus he is allowed to choose his own wife, so long as she is a suitable addition to the Sanada clan...and she meets his Must Haves list.

MC doesn’t have wealth, isn’t of a noble lineage, nor does she bring in any sort of plentiful dowry...But that is 1 miss versus hitting every. other. requirement. on Nobyuki’s Wifey Must Haves list.

Even before meeting her, he’s already decided that - once he has all the information on her collected (I’ll give him credit, he DID initially think this “interesting new retainer” of Shingen’s was a Uesugi spy so it’s not like he was just...randomly choosing young women to look into) - her actions demonstrate her courage and she might be just what he needs. For a few things. Jinpachi may have well confirmed or denied this since he’s been keeping an eye on MC for Nobuyuki until he got there.

Once he’s made his decision, he will stick to it because it would be a waste of (multiple) opportunities.

He didn’t think, of course, that he might catch Feelings (his ES also shares this in common), but really, when does anyone?

Insert drama.

In the end, he is able to have/keep the woman he’d chosen and she loves him and accepts him for who he is. According to her. Granted she sees him as more mischevious than dangerous, BUT, when you love a yandere wholeheartedly and they love you, I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s the overall perception???

They’ll be married, soon, and according to Buyan, he wants to be married a-fucking-sap. Enthusiasm? Honestly, I’m sure he does feel that. Officially binding the two of them together? Most certainly plays a part, too.

And thus: Nobuyuki loves MC and she loves him. He will do anything & everything he can to make her happy regardless that his foremost obligation is to prioritize his clan above all else.

He will ensure that she is so happy, so enraptured, SO in love with him...that her thoughts will be saturated with little else BUT him (he goes so far as to label this desire of his as a need of his). MC will NOT end up dissatisfied with him, she will NOT feel neglected feeling due to his duties...and as for him?

His bride. His wife [to-be]. His MC (he does refer to MC as his [MC’s name] in the Divine end. Divine end epilogue? UGH IF ONLY I HAD MY SCREENSHOTS). The woman he chose to fulfill one of the (few) obligations that he had (arguably) the most control over...is everything he could have expected. Even, dare I say, hoped for.

MC bypassed Nobuyuki’s Very High and Specific Requirements and captured his heart utterly. Just as he’s captured her and her heart.

Regardless of some short-term surprise on his clan/father’s behalf, they all accept his explanation that she is exactly what the Sanada clan needs. And his clan does, in fact, fall in love with her. His father approves of her, regardless of her common birth, and Yukimura is SO enthusiastic about the two of them and is so happy for his brother - for the both of them.

MC, in turn, accepts and loves them as her own family & clan (because they are as such now). She has promised herself to him and has promised to be with him through those heart-gripping times of waiting and the unknown, to support him in any way she can, and to stand at his side always. She is determined to do all she can as a Sanada bride, as the heir’s wife. As Nobuyuki’s wife.

His. His wife. His choice. His his his his HIS.

The bride, the wife, the woman he specifically chose for himself. Likely one of the very few, if next to never, self-serving choices he’s made. All wrapped up in an honest boon to the clan. An excellent decision, one that is trusted and accepted, that isn’t countered.

In my perspective, this utter...obsessive devotion, this possessive love, is likely fueled by the fact that a selfish decision on his part worked for beyond the good he could have expected and now he is never going to let her go. And he’s never going to allow anyone to threaten their happiness, their relationship, ever. Her eyes might remain on him, and he wants them too, and while he rains affection on her, he’ll have those who so much as stare at her too long thoroughly understand the risks (and even consequences) of such poorly thought out actions.

Thx for coming to my Excessively, Unnecessarily Long TedTalk on some minor...analysis of a small portion of Nobuyuki’s yandere thought process in relation to his MC.

#slbp#slbp nobuyuki#kae speaks tag#( is this a character analysis or just an overdrawn ramble )#( we may never know )

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can't quite remember what I said but first I know I was thanking you for answering the questions so thoroughly and that I also enjoy Elliot. Partially b/c as u say, the flaws, but also b/c he does try to fight some of his less enlightened thinking. He is honest in his responses which is refreshing. His views might not be pleasant but characters aren't stabbed in the back by him. And, as you say, he does evolve as the show continues

was in the writer’s room to give him an emotionally and physically abusive father and a bipolar, unmedicated mother but that literally gave him no healthy relationships to model his behavior as a young child. In regards to E/O, my question wasn’t so much why isn’t Olivia in an f/f relationship, but more how you see the relationship which you answered nicely. I can’t ever actually see them being sexual unless being totally off the job b/c I think they’d be totally afraid of screwing up the best relationship they had and I’m saying this even though I like Kathy. E/O trust one another implicitly and even though they hurt one another, the trust was deep enough to survive, excepting of course, how Elliot left which I agree was a poor choice on the part of the writers. They could have mentions once in awhile about hearing from Elliot, texts, phone calls that wouldn’t take time away from the storyline. Instead, the inexplicable silence which is completely OOC in regards to Olivia.

[first post if anyone wants context]

This whole ask/reply is a little all over the place but hopefully it makes sense! I think my inbox has been eating asks, so thank you for resending the start.

But yeah, your points are other reasons I love Elliot’s character. He tries, maybe not always and maybe not perfectly, but he does and I think that’s important. It’s one of those little traits that makes me soft for him.

no healthy relationships to model his behavior as a young child

This is actually a really interesting point that I haven’t thought about much. I don’t have a whole lot to say about it now but give me a day or two and I’m sure I could write another essay.

I can’t ever actually see them being sexual unless totally off the job…

Okay, yes! When it comes to writing fic, I like playing with the idea of E/O in a romantic or sexual relationship while partners because it’s fun and there’s so much canon content to work with, but if I had to pick like, a preference for them getting together, it’d actually be after Elliot’s retirement.

I think him leaving opens a door for their relationship to develop past a partnership, and I think, if they’d kept in contact, that development would come naturally. Slowly, probably, but that’s expected. I think they’d struggle at adjusting to a new normal—they’d need to figure out how to navigate their friendship outside of a partners-context, but once they did, it’d be like. The perfect opportunity to turn into something more.

(I also don’t think Elliot’s marriage would survive his retirement. This isn’t even like, a shippy thing. I really like Kathy but their relationship never came across as particularly stable—even before the first near-divorce—and I think without the job to blame a lot of their issues on, they’d realise that it was never just that). ((I’m so close to going off on a tangent about my headcanons for Elliot post-s12 but I literally Won’t Shut Up, so I’ll hush now).

afraid of screwing up the best relationship they had

Yesssssss. This is actually something that draws me to them.

I think the fear of ruining their friendship/partnership would stop them from acting on their desire, but that doesn’t eliminate the desire, and two people being in love without being able to do a damn thing about it?? It’s one of my favourite fiction tropes for romantic relationships. And in the context of E/O it hits almost all of my buttons.

…excepting of course, how Elliot left, which I agree was a poor choice on the part of the writers. They could have mentions once in awhile…

Anon, I swear you’re inside my head.

I don’t know if this is unpopular or not, but I actually like that Elliot left. Not the show, but the unit. It makes sense to me that he’d retire after the incident with Jenna—I really cannot see him handling the guilt well. He’d internalise it, he’d beat himself up over it, and you know he wouldn’t talk about it. Wouldn’t seek help for it. I can even believe that he’d isolate himself after it; that he’d separate himself from the job (read: Olivia) until he could wrap his head around the whole thing.

What I can’t believe is that he’d just disappear into thin air without a goodbye. Or even that Olivia would let him. A casual line every now and then to suggest that Liv still talks to him would be everything, but honestly? I wouldn’t be half as annoyed if they’d just kept the bloody Double Strands deleted scene. It’s the closest thing to closure we have and I hate that they didn’t add it to the episode.

#sorry if this response isn’t as in depth as the other one. i just got home from work and i’m exhausted.#but i wanted to post something because… i love talking about my boy#ask#anonymous#elliot stabler#eo

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Sacraments In Scripture - Part 8

CHAPTER 8

SACRAMENTS

OF MARRIAGE

Overview

At the very creation of man and woman, God instituted marriage:

God who created man out of love also calls him to love—the fundamental and innate vocation of every human being. For man is created in the image and likeness of God who is himself love. Since God created him man and woman, their mutual love becomes an image of the absolute and unfailing love with which God loves man (Catechism, no. 1604).

The vocation to the Sacrament of Marriage is a call for men and women in their marital (and familial) relationship to imitate the kind of love which is characteristic of God—a love that is absolute, unfailing, sacrificial, and life-giving. Marital love is to be a godly love.

Old Testament

Since the nature of Trinitarian love is “absolute and unfailing,” marital love is to be exclusive and permanent in order to truly embody the love of God. Because of this, we may often find it troublesome when we encounter many of the great figures of the Old Testament, such as some of the patriarchs or the kings of Israel, who repeatedly “transgress” what we know to be the truth of marital love. The Catechism teaches that in the Old Testament God allows certain practices because of man’s “hardness of heart”(Catechism, no. 1610). If we read the biblical narrative carefully, however, we can see that even while allowing such practices, God is teaching His people the truth of marital love by the consequences that result when the fullness of His design is not lived out. The Bible subtly shows that when marriage is not exclusive and permanent, it often leads to bad results. So, for example, when Abraham took Hagar as a concubine, she bore Ishmael, and the result was a brotherly battle between the Israelites and the Ishmaelites (modern-day Arabs) that continues to this day. When Lot slept with his daughters, they bore Amon and Moab, from whom the Ammonites and the Moabites descended, and with whom the Israelites were constantly at war. When Jacob took two wives and two concubines, he sowed the seeds for family division, which was demonstrated when Joseph was sold into slavery by his brethren and again later when there was division among the twelve tribes. When Solomon took many wives, he disobeyed the law for kings given by Moses, which provides that the king “shall not multiply wives for himself, lest his heart turn away” (Deut. 17:17). Solomon’s heart did turn away from Yahweh (cf. 1 Kings 11:4) and, because of his divided heart, the kingdom of Israel was divided in civil war during the reign of his son Rehoboam (cf. 1 Kings 12). By showing us such disastrous effects, these biblical narratives implicitly teach us God’s design for marriage at creation.

The true nature of marital love is most clearly demonstrated by Yahweh Himself in His covenant relationship with Israel. The prophets spoke of Israel’s covenant relationship with Yahweh as a marriage covenant. Yahweh is described as Israel’s husband: “For your Maker is your husband” (Is. 54:5). In Ezekiel the Lord describes how His covenant with Israel is a marriage covenant: “I plighted my troth to you and entered into a covenant with you, says the Lord GOD, and you became mine” (Ezek. 16:8).

Seeing God’s covenant with Israel in the image of exclusive and faithful married love, the prophets prepared the Chosen People’s conscience for a deepened understanding of the unity and indissolubility of marriage (Catechism, no. 1611).

Since Israel is covenanted to Yahweh, Israel’s worship of idols is considered marital infidelity, thus the Lord refers to Israel as an “adulterous wife” (Ezek. 16:32). Through Jeremiah, God describes how Israel broke the covenant made at Sinai, “though I was their husband” (Jer. 31:32). Yet, despite Israel’s unfaithfulness, Yahweh is steadfast in His covenant love and faithfulness.

Above all, it is through the prophet Hosea that God illustrates the marital relationship that the covenant creates between Himself and Israel. God tells Hosea to take a harlot named Gomer, for a wife. Gomer’s infidelity to Hosea is a sign of Israel’s marital infidelity to Yahweh. The Lord says to Hosea, “Go, take to yourself a wife of harlotry and have children of harlotry, for the land commits great harlotry by forsaking the LORD” (Hos. 1:2). The Lord then reveals to Hosea that in the future He will make a new covenant with Israel, a covenant that will mark a new and faithful marriage relationship between God and His people.

And I will betroth you to me for ever; I will betroth you to me in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy. I will betroth you to me in faithfulness; and you shall know the LORD (Hos. 2:19-20).

The Lord tells Hosea that He shall woo Israel by taking her out to the wilderness, where He shall “speak tenderly to her” (Hos. 2:14). Just as Yahweh led Israel into the wilderness in the Exodus and made a covenant with her at Sinai, so too, He will once again take Israel out into the wilderness before ratifying the New Covenant. It is not accidental, then, that the New Testament begins with Israel’s going out to the wilderness to hear John the Baptist, who calls himself the “friend of the bridegroom” (Jn. 3:29).

New Testament

According to Saint John’s Gospel, Jesus performed His first sign, which marked the beginning of His public ministry, while attending a wedding feast in Cana.

The Church attaches great importance to Jesus’ presence at the wedding at Cana. She sees in it the confirmation of the goodness of marriage and the proclamation that thenceforth marriage will be an efficacious sign of Christ’s presence (Catechism, no. 1613).

Not only did Jesus perform a miraculous sign at the wedding when He changed the water into wine, His very presence at the feast was a sign of the nature of His mission and of the restoration and elevation of marriage that He was bringing about.

When Jesus is questioned by the Pharisees about Moses’ allowance for divorce, He reminds them of God’s original plan for marriage:

Have you not read that he who made them from the beginning made them male and female, and said, “For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one”? So they are no longer two but one. What therefore God has joined together, let no man put asunder (Mt. 19:4-6).

According to Jesus, divorce and the breakdown of marriage is the result of sin: “For your hardness of heart Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so” (Mt. 19:8). Jesus makes it clear that marriage is intended to be exclusive (monogamous) and permanent, and thus in His response to the Pharisees He restores to marriage its original dignity.

Jesus not only restores marriage to its original design, He elevates marriage to a sacrament. This means that marriage is not simply a sign, but a sign that effects grace. Jesus is the bridegroom and, through the New Covenant, He makes the Church His bride. Marriage between a man and a woman signifies the love of Christ and His bride the Church (cf. Catechism, no. 1617). As we saw above, the People of God were often unfaithful to the commitment of marriage, both individually and corporately. Indeed, this is reflected at the national level by Israel’s covenant unfaithfulness to Yahweh. But in the New Covenant, Jesus bestows upon marriage sacramental graces that enable men and women to be faithful to their marriage vows. Likewise, in the New Covenant, the bride of Christ is given the graces to be faithful to her divine spouse. This is what Hosea had foretold when he spoke of how Yahweh would enter into a new covenant marked by fidelity and love.

Jesus often alluded to the fact that He is the bridegroom, and His bride is the Church. For example, when asked why the disciples of John the Baptist and the Pharisees fast, and His do not, He replied:

Can the wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them? As long as they have the bridegroom with them, they cannot fast. The days will come, when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will fast in that day (Mk. 2:19-20).

This may seem like a strange response to us, but it made sense to Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries. In Jesus’ day, the Jews would celebrate a wedding feast for an entire week. The Pharisees had the custom of fasting twice a week, but they were exempt from fasting if they were attending a wedding celebration. Jesus refers to this custom to explain that His disciples are like the friends of a bridegroom during the wedding feast, and thus it is inappropriate for them to fast. However, Jesus does point out that a day will come when the bridegroom is taken away—a reference to His death—and then His disciples will fast.

Jesus often employed the imagery of a wedding feast in His teaching. Marriage was more than a metaphor to Jesus; often, it was a thinly veiled allusion to His kingdom. For example, Jesus says:

The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a marriage feast for his son, and sent his servants to call those who were invited to the marriage feast (Mt. 22:2-3).

The invitation to the feast signifies how Israel has been summoned to follow Jesus and enter into the kingdom of God. As it is in the parable, so it is in the ministry of Jesus: The invitation is rejected. Jesus uses this parable to show that God the Father has prepared a wedding feast for Him—the Son. This interpretation of the parable is confirmed by the Book of Revelation, where Saint John sees history climaxing in the wedding feast for Jesus and His bride the Church. The angel who shows Saint John the vision of the wedding exclaims, “Blessed are those who are invited to the marriage supper of the Lamb” (Rev. 19:9). Earlier, when Saint John recorded the events at the wedding feast of Cana in his Gospel, he made no mention of the names of the bride and bridegroom. Some of the Fathers of the Church believe this is intentional, to show that Jesus is the true bridegroom and the Church is His true bride.

Application

For those who have been called to the Sacrament of Marriage, the biblical accounts should renew our commitment to live out our marital vocation to the fullest. The covenant between spouses is integrated into God’s covenant with man: “Authentic married love is caught up into divine love” (Catechism, no. 1639). The vocation of marriage should be a clarion call to each spouse to witness to the unconditional, steadfast, and everlasting love of our God. Each marriage should be an earthly icon of the love of Christ and the Church. Indeed, Saint Paul calls the Sacrament of Marriage a “great mystery” (Eph. 5:32), because it represents the spousal relationship between Jesus and His bride, the Church.

The love of Christ for the Church, and vice versa, is therefore a model for married couples. Saint Paul elaborates on this marital spirituality when he says, “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Eph. 5:25). The way we love our spouse is to be a blueprint for how we should love Christ. Conversely, the ways in which we fail to love our spouse is often a sign of how we fail to love God. Marriage provides lessons in love that need to be contemplated so as to deepen our desire and ability to love God.

One of the great privileges and responsibilities of married love is openness to new life. God has blessed marriage from the beginning, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 1:28). In this way, family fruitfulness gives witness to the life-giving power of love. Thus the Second Vatican Council and the Catechism observe:

Hence, true married love and the whole structure of family life which results from it, without diminishment of the other ends of marriage, are directed to disposing the spouses to cooperate valiantly with the love of the Creator and Savior, who through them will increase and enrich his family from day to day (Catechism, no. 1652; cf. GS 50).

Love is generous, and true love is modeled on the divine, which is self-giving.

The rich biblical teaching on marriage is not exclusively for those who are called to married life. All Christians, both individually and as members of the Church, are called to be as a bride to Christ our bridegroom. Indeed, the saints and doctors of the Church often describe the relationship between God and the soul, in the third and final stage of the interior life, as being spousal. Saints such as John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila refer to the soul as the bride of Christ. The Catechism refers to the spousal nature of the Christian life:

The entire Christian life bears the mark of the spousal love of Christ and the Church. Already Baptism, the entry into the People of God, is a nuptial mystery; it is so to speak the nuptial bath which precedes the wedding feast, the Eucharist (Catechism, no. 1617).

As we grow in the Christian life, the relationship between the soul and God is to be that of a marital covenant: steadfast, ever-lasting, sacrificial, and fruitful. Saint Paul reminds us of how we are called to be pure and loving brides to Jesus our bridegroom, when he says, “I feel a divine jealousy for you, for I betrothed you to Christ to present you as a pure bride to her one husband” (2 Cor. 11:2).

Questions

1. When did God create marriage? (See Genesis 2:23-25; Matthew 19:4-6.)

2. How are the effects of sins against marriage revealed in the lives of some of the Old Testament patriarchs and kings?

a. Genesis 19:36-38

b. 2 Samuel 11:1-5, 12:7-15

c. 1 Kings 11:1-13

3. How do the prophets characterize Israel’s covenant relationship with Yahweh?

a. Isaiah 54:5

b. Ezekiel 16:8

4. How does Hosea, in his own life, embody Yahweh’s covenant relationship with Israel? (See Hosea 1:2.)

5. Read Matthew 19:8. According to Jesus, why did Moses allow for divorce?

6. Read Ephesians 5:21-33. How is the relationship between spouses to imitate the relationship between Christ and the Church?

7. How is marriage a sign of the spiritual life of the soul? (See Catechism, no. 1617.)

8. For each of the following properties of the marriage bond, how does authentic married love signify and bear witness to the love of God?

a. monogamy

b. indissolubility

c. fruitfulness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dorf on the stakes of the Originalism/Textualism debate

On his blog, Dorf on Law, Cornell law professor Michael Dorf has a very thoughtful and measured assessment of The Stakes of the Originalism/Texualism Debate. In it, he starts with the proposition that, with the confirmation of self-described originalist Neal Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, originalism is here to stay for the foreseeable future. With this in mind, he sets out to examine the stakes in this debate. He does so in a clear-eyed and nuanced manner, and I recommend you read the whole thing.

In this post, I want to highlight his two key moves. First, he makes the increasingly familiar claim that, if original meaning is taken at a sufficiently high “level of generality,” there may be very little difference between the results of an originalist and nonoriginalist evaluation of constitutional meaning. Here is how he puts the matter:

What makes originalism ostensibly distinct from other views is what Prof. Larry Solum has called the “fixation thesis”–the notion that the meaning of a provision is fixed at the moment of its enactment–and the “constraint thesis”–the notion that this fixed meaning constrains constitutional practice. One can concede both points to Solum and concede further that whether judges accept these theses affects how they write opinions justifying their rulings. However, for reasons similar to those elaborated on this blog last week by Prof. Eric Segall in describing a recent article by Prof. Peter Smith, I think that whether a judge accepts Solum’s theses has little immediate practical impact. Nonetheless, the stakes in the debate over originalism are not as low as one might think, as I shall explain.

As Smith and Segall and others have argued, if a judge believes that the original meaning of a constitutional term is best understood at a high level of generality, then the constraint principle does little constraining. “Equal protection” is a good example. Most of the framers and ratifiers almost certainly thought that most forms of de jure sex discrimination were consistent with equal protection of the laws, but, as nearly all contemporary originalists would say, the framers’ and ratifiers’ concrete intentions and expectations do not define the meaning of the term equal protection. To the extent that we care about intentions and expectations as evidence of meaning, we care about semantic intentions and expectations. If, say, as some originalists argue, the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment was a prohibition on state laws redolent of caste distinctions, then sex discrimination is presumptively invalid today, because we now recognize, as our nineteenth century forebears did not, that sex-based distinctions generally are caste-like distinctions.

Thus, where a “living Constitutionalist” might say that the meaning of equal protection evolved between 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was enacted, and 1973, when the Supreme Court decided Frontiero v. Richardson, a semantic originalist would say that the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment was constant all along. In this example, Solum’s constraint principle would constrain the rhetoric of a modern sex discrimination case, but it would not constrain the outcome. Both originalists and living constitutionalists who think that sex discrimination violates contemporary notions of equality would treat such discrimination as presumptively invalid.

That is not to say that there cannot be cases in which the choice between accepting Solum’s two theses and rejecting them makes a difference. But it is to say that in the cases that are most divisive–which involve constitutional provisions that are naturally read at a high level of generality–the choice will not be decisive.

A couple thoughts on this premise. When I published my 1999 essay, An Originalism for Nonoriginalists, I asserted that, properly understood, original public meaning originalism offered progressives many more favorable results than they had assumed. So I agree with some of this. I don’t want to spend too much space on this premise of Dorf’s (and Smith and Segall), so I will limit myself to two observations:

First, this claim implicitly concedes that the original meaning of most of the Constitution–what Sandy Levinson has called the “hard-wired” part of the Constitution–is determinate enough to yield results. The “fixed” original meaning of “state” is definite enough to apply to California–though California was not imagined at the time of enactment–and so is the text that allocates two senators to California irrespective of its population. Why, I ask, should we follow this text today if the original meaning is not “fixed” and does not “constrain” current legal decision makers? Put another way, why would a living constitutionalist who rejects either the fixation thesis or the constraint principle adhere to the text here if doing so violates his or her deeply held commitment, say, to “one-person-one vote”? Perhaps an academic could take this view, but could any Democratic judicial nominee be confirmed by even a Democratic-controlled Senate if she candidly claimed the power to override this express constitutional constraint?

Second, I doubt that the handful of “constitutional provisions that are naturally read at a high level of generality” are nearly as general as typically claimed by nonoriginalists. For example, the words “equal protection” does not appear as a free standing “equality principle,” but appears in the phrase “equal protection of the law” and this passage is embedded in a larger clause that also refers to the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States” (which no state statute may abridge) and the “due process of the laws” (which no state shall deny when depriving a person of life, liberty, and property).

Read in their entirety–and in context– the “natural” reading of these provisions may be far less general than is claimed. In particular, in context, the original meaning of the “equal protection of the law” may refer to the affirmative governmental duty of protection or equal enforcement “of the law”–that is, statutes that are otherwise constitutional (because such laws are not violative of either the Privileges or Immunities or the Due Process of Law Clauses). I cannot substantiate this claim here but, if true, it would make the original meaning of the “general” clauses far less underdeterminate, which would reintroduce a gap between public meaning originalism and living constitutionalism.

But for now, I want to take Professor Dorf’s charitable assumption about happy results as given and consider his second move, which is the heart of his claim about the remaining stakes of the debate:

2) Bait and switch. The fact that originalists and living constitutionalists often reach the same outcomes in concrete cases does not necessarily mean that the practical stakes are low, because even as, in academic circles concrete-expectations-and-intentions originalism has given way to semantic originalism in the last three-plus decades, in public debate originalism means concrete-expectations-and-intentions originalism. I will cheerily concede that the academics who propound semantic originalism thereby intend only to work out what they regard as the best (or what many of them think is the only legitimate) approach to constitutional interpretation and construction, without any regard for the political consequences. But even if unwittingly, in doing so the academics enable concrete-expectations-and-intentions originalism–which has a conservative, even reactionary, bias–to flourish.

I made this point at length in a 2012 essay in the Harvard Law Review, in which I reviewed Balkin’s Living Originalism and Prof. David Strauss’s The Living Constitution. Here is a small sample of what I wrote there:

“Widespread acceptance of Balkin’s views would allow conservatives to say that even liberals now accept originalism but then turn around and define originalism narrowly. Balkin and other leading “new” originalists like Professors Randy Barnett, Lawrence Solum, and Keith Whittington make originalism respectable by answering objections leveled at “expectations-based originalism” — but judges, elected officials, and the public misuse the credibility that these scholars lend to originalism more broadly by relying on evidence about the framers’ and ratifiers’ expected applications in considering concrete cases.”

Thus, although the scholars would never say that there can be no Fourteenth Amendment right to abortion or same-sex marriage simply in virtue of the fact that most members of the Reconstruction Congress and the general public in 1868 thought there was no such right, politicians and justices who, during their confirmation hearings talk the talk of semantic originalism, make just such academically discredited arguments in reliance on the framers’ and ratifiers’ concrete expectations and intentions.

The stakes are high because academic originalism–even if through no fault of academic originalists–legitimates reactionary jurisprudence. [My italics added.]