#like artists are gatekeeping art rather than developing their skills

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Well in the end it comes down to recognizing when you can’t have a good faith conversation. I can understand the arguments being made and where it comes from but I fundamentally disagree with some of the foundations of these beliefs and will not budge. Nuance necessitates some alignment, I think.

#my ramblings#at this moment I don’t think you can separate the conversation of ai as a tool from the CURRENT ONGOING ethical issues#this isn’t theoretical it is right now for real being used in a specific way#if you’re curating your own datasets (??) for training (???) obviously there are ways to address it#but the major tools being used#are largely unethical full stop#and go beyond ‘unethical but you kind of can accept it and it’s necessary for day-to-day life’#in my opinion at least#there are ai tools that can be used without exploiting artists#like yknow filters or some of those color tools or van gogh generator#van gogh’s dead so it’s not really exploitation of his art unless it’s like. I dunno. sold as if it were a commission#instead of an ai generated product#plus I feel like some of the arguments I’ve read frame things in kinda weird way#like artists are gatekeeping art rather than developing their skills#and there are unproductive ways to frame arguments that raise concerns about ai#but making it about the argument rather than the tool is missing the forest for the trees#well yknow how it is#I simply won’t see those takes anymore

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'know I think the reason why I hate the term "content creator" isn't necessarily the word choice of calling stuff posted online "content". Superficially I don't think it's a bad idea to have an intentionally vague catch-all term a la "queer" that ensures gatekeeping is difficult by definition.

I think the actual reason why I hate the term "content creator" is that it places overwhelming focus on the end product, not on creation as a process or skillset. "Artist" "writer" "documentarian" "musician" or even a vague catch-all term like "creative" is much nicer to me because it's a term that places the emphasis on the human being and their skills and craft, rather than the output. If anything defines me it's not the actual final pictures I post on the internet, but the skills and techniques and methods of thinking I've incorporated into my being over my lifetime. Even with clients, the point of a portfolio isn't so much us showing off what we've created in the past, but is rather simply a means to demonstrate what skills we have developed. At a broader scope, it's also why a resumé is a list of skills, degrees, and workplace experiences first and foremost, with specific final outputs and projects being secondary if mentioned at all.

Conversely, "content creator" reduces all of that to the end product. It's a phrase that suggests a disinterest in the how and almost exclusively on the what. Here you're defined not by what skills you have as a person, but rather on what your output is: you are a creator of content, and the content is what's actually important above all else. The "creator" in "content creator" is but a mere means to an end, and the thing about being viewed as a means-to-an-end is that the people in charge will want to replace you with something more efficient if it'll result in the same end, in their mind.

Over the years we've been seeing the ongoing trivialisation of creatives at large: not just the NFT and AI art drivel, but also the replacement of practical effects and sets with CG solely because those workers are cheaper, the abuse of video game developers, the erosion of selling music as a viable income stream, the normalisation of spec work from writers and graphic designers, the list goes on. All of these events and more, in my view, have the same undercurrent of viewing final products and results as the most important thing in the creative process; care for the human beings who actually make the things is secondary at best.

Hence I don't think that a lot of the observations people make about tech dudebros flip-flopping between "art is immutably valuable and unique" for NFTs and "art is basically all the same and interchangeable" with AI isn't necessarily hypocrisy, because when you understand that these people view the tangible but inanimate final product, an entity that demands nothing of you nor will invite any protest if reduced to a single number on a spreadsheet, as the most important thing? Of course they have no problem doing both. It's also why you can't actually engage with these people on good faith; at the end of the day trying to appeal to their sense of morality when it comes to the welfare of human beings is not really what they're interested in, frankly.

It's the mass acceptance of "so long as we get the results, I don't care how we go about achieving them" which honestly freaks me out the most.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

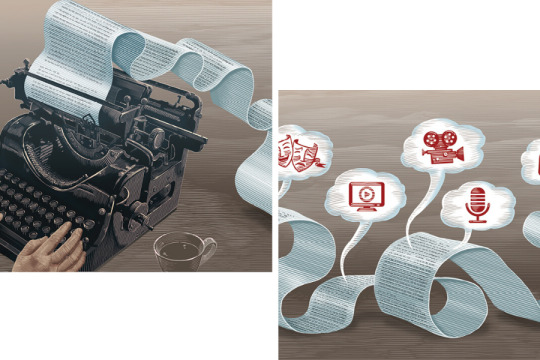

Watch This Space: Playwrights Train for All Media

As dramatists begin to write for all media, the nation’s playwriting programs are starting to teach beyond the stage.

BY MARCUS SCOTT

In 2018, a record 495 original scripted series were released across cable, online, and broadcast platforms, according to a report by FX Networks. And with the growing popularity of streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon (not to mention new players like Disney and Apple), a whopping 146 more shows are up and running on various platforms now than were on air in 2013. So how does peak TV relate to theatre?

Once a way for financially strapped playwrights to land stable income and adequate health insurance, television has since emerged as a rewarding venue for ambitious dramatists looking to forge lifetime careers as working writers. Playwright Tanya Saracho is the current showrunner for “Vida” on Starz. Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa is the series developer of “Riverdale” and “Chilling Adventures of Sabrina.” Sheila Callaghan is executive producer of the long-running black comedy “Shameless.” Sarah Treem, co-creator and showrunner of “The Affair,” recently concluded the Rashomon-esque psychological drama in November.

To satiate demand for more content, showrunners have sought to recruit emerging playwrights to fill their writers’ rooms. It’s now common practice for them to read plays or spec scripts penned prior to a writer’s graduation.

Many aspiring playwrights have caught on, enrolling in drama school intent on flirting with virtually every medium under the umbrella of the performing arts. Several institutions around the country have become gatekeepers for the hopeful—post-graduate MFA boot camps bestowing scribes with the Aristotelian wisdom of plot, character, thought, diction, and spectacle before they’re dropped into the school of hard knocks that is the modern American writers’ room. Indeed, since our culture has emerged from the chrysalis of peak TV, playwriting programs have begun training students for a career that includes not only the stage but multiple mediums, including the screen.

Playwright Zayd Dohrn, who has served as both chair of Northwestern University’s radio/TV/film department and director of the MFA in writing for screen and stage since 2016, said versatility is the strongest tool in the kit of the program’s students.

“We offer classes in playwriting, screenwriting and TV writing, as well as podcasts, video games, interactive media, stand-up, improv, and much more,” he explained. “There’s no one way to approach the craft, and we offer world-class faculty with diverse backgrounds, professional experiences, and perspectives, so students can be exposed to the full range of professional and artistic practice.”

Dominic Taylor, vice chair of graduate studies at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television in California, also agrees that multiplicity is the key to the survival of a working writer. “In the industries today, whether one is breaking a story in a writers’ room or writing coverage as an assistant, the ability to recognize and manipulate structure is paramount,” Taylor said. “The primary skill, aside from honing excellent social skills, would be to continue to study the forms as they emerge. Read scripts and note differences and strengths of form to the individual’s skill set. For example, the multi-cam network comedy is very different from the single-cam comedy—‘The Conners’ versus ‘Modern Family,’ let’s say. It’s not just the technology; it is the pace of the comedy.”

Taylor, a distinguished multi-hyphenate theatre artist working on both coasts, said that schools like UCLA offer a lot more than classes, including one with Phyllis Nagy (screenwriter of Carol). UCLA’s program also partners with its film school, and hires professional directors to work with playwrights to develop graduate student plays for productions at UCLA’s one-act festival, ONES, or its New Play Festival. Taylor also teaches four separate classes on Black theatre, giving students the opportunity to study the likes of Alice Childress, Marita Bonner, and Angelina Weld Grimké in a university setting (a rarity outside of historically Black colleges and universities).

Dohrn, a prominent playwright who is currently developing a feature film for Netflix and has TV shows in development at Showtime, BBC America, and NBC/Universal, said that television, like theatre, needs people who can create interesting characters and tell compelling stories, who have singular, unique voices—all of which are emphasized in playwriting training.

“Playwrights are not just good at writing dialogue—they are world creators who bring a unique vision to the stories they tell,” Dohrn emphasized. “More than anything else, a writer needs to develop his/her/their unique voice. Craft can be taught, but talent and creativity are the most important thing for a young writer.”

For playwright David Henry Hwang, who joined the faculty at Columbia University School of the Arts as head of the playwriting MFA program in 2014, success should be a byproduct, not a destination. “As a playwright, I don’t believe it’s possible to ‘game’ the system—i.e., to try and figure out how to write something ‘successful,’” he said. “The finished play is your reward for taking that journey. The thing that makes you different, and uniquely you, is your superpower as a dramatist, because it is the key to writing the play only you can write. Ironically, by focusing not on success but on what you really care about, you are more likely to find success.”

Since arriving at Columbia, one of Hwang’s top priorities was to expand the range of TV writing classes. This led to the creation of separate TV sub-department “concentrations,” housed in both the theatre and film programs. All playwriting students are required to take some television classes.

“We are at a rather anomalous moment in playwriting history, where the ability to write plays is actually a monetizable skill,” said Hwang, whose TV credits include Treem’s “The Affair.” “Playwrights have become increasingly valuable to TV because it has traditionally been a dialogue-driven medium (though shows like ‘Game of Thrones’ push into more cinematic storytelling language), and playwrights are comfortable being in production (unlike screenwriters, some of whom never go to set). Once TV discovered playwrights, we became more valuable for feature films as well.”

Playwrights aren’t the only generative theatremakers moving to the screen. Masi Asare is an assistant professor at Northwestern’s School of Communication, which teaches music theatre history, music theatre writing and composition, and vocal performance. The award-winning composer-lyricist, who recently saw her one-act Mirror of Most Value: A Ms. Marvel Play published by Marvel/Samuel French, said that the world of musical theatre is not all that different either; it’s experiencing a resurgence in both cinema and the small screen: Lin-Manuel Miranda, Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez, Justin Hurwitz, and Benj Pasek and Justin Paul have all written songs that were nominated for or won Oscars. The growth of YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter have offered new ways for musical theatre graduates to market and monetize their songs and build an audience.

“The feeling that a song has to ‘work’ behind a microphone in order to be a good song is really having an impact on young writers,” said Asare. “The song must sound and look good in this encapsulated video that will be posted on the songwriters’ website and circulated via social media.” She noted that in this case, the medium of video is also changing the medium of musical theatre itself. “Certainly it may lead to different kinds of musicals—who knows? New experimentation can be exciting, but I think there is a perception that all you have to have is a series of good video clips to be a songwriter for the musical theatre, a musical storyteller. I think that does something of a disservice to rising composers and lyricists.”

Some playwriting students, of course, are not interested in learning about how to write for television. But many who spoke for this story agreed that learning about the different ways of storytelling can be beneficial. One program in particular that has its eyes on the multiplicity of storytelling mediums is the Writing for Performance program at the California Institute of the Arts. Founded by playwright Suzan-Lori Parks in 2001 as a synergy of immersive environments, visual art installation, screenplay, and the traditional stage play, the program has helped students and visiting artists alike transcend theatrical conventions. Though Parks is no longer on the CalArts faculty, her spirit still infuses the program. As Amanda Shank, assistant dean of the CalArts School of Theater, puts it, “Every time she came to the page, there was a real fidelity to the impulse of what she was trying to communicate with the play, and the form followed that. It’s not her trying to write a ‘correct’ kind of play or to lay things bare in a certain prescribed way.”

That instinct is in the life fiber of CalArts’s Special Topics in Writing, a peer-to-peer incubator for the development of new projects that grants students from across various departments the opportunity to develop and produce writing-based projects. Shank defines the vaguely titled yearlong class, which she began, as a “hybrid of a writing workshop and a dramaturgical project development space.” A playwright and dramaturg, Shank said her class was born of her experience as an MFA candidate; she attended the program between 2010 and 2013, and then noticed her fellow students’ lack of ability to fully shepherd their projects.

“I was finding a lot of students that would have an idea, bring in a few pages or even bring in a full draft, but then they would kind of abandon it,” said Shank. “I wanted a space [that would] marry generative creativity, a place of accountability, but also a place that was working that muscle of really developing a project. Because I think often as artists we look to other institutions, other people to usher our work along. Yes, you need collaborators, yes, you need organizations of supporters—but you have to some degree know how to do those things yourself.”

Program alum Virginia Grise agrees. Grise has been a working artist since her play blu won the 2010 Yale Drama Series Award. She conceived her latest play, rasgos asiaticos, while still attending CalArts. Inspired by her Chicana-Chinese family, the play has evolved into a walk-around theatrical experience with some dialogue pressed into phonograph records that accompany her great uncle’s 1920s-era Chinese opera records. After developing the production over a period of years, with the help of CalArts Center for New Performance (CNP), Grise will premiere rasgos asiaticos in downtown Los Angeles in March 2020, boasting a predominantly female cast, a Black female director, and a design team entirely composed of women of color. Her multidisciplinary work is emblematic of the direction CalArts is hoping to steer the field, with training that is responsive to a growingly diverse body of students who may not want to create theatre in the Western European tradition.

“You cannot recruit students of color into a training program and continue to train actors, writers, and directors in the same way you have trained them prior to recruiting them,” said Grise. “I feel like training programs should look at the diversity of aesthetics, the diversity of storytelling—what are the different ways in which we make performance, and how is that indicative of who we are, and where we are coming from, and who we are speaking to?”

As an educator whose work deals with Asian American identity, including the play M. Butterfly and the high-concept musical Soft Power, Hwang said that one of his goals as an educator is to train a diverse body of students and teach them how to write from a perspective that is uniquely theirs.

“If we assume that people like to see themselves onstage, this requires a range of diverse bodies as well as diverse stories in our theatres,” Hwang said. “Institutions like Columbia have a huge responsibility to address this issue, since we are helping to produce artists of the future. Our program takes diversity as our first core value—not only in terms of aesthetics, but also by trying to cultivate artists and stories which encompass the fullest range of communities, nationalities, races, genders, sexualities, differences, and identities.”

The film business could use similar cultivation. In March 2019, the Think Tank for Inclusion and Equity (TTIE), a self-organized syndicate of working television writers, published “Behind the Scenes: The State of Inclusion and Equity in TV Writing,” a research-driven survey funded by the Pop Culture Collaborative. Data from that report observed hiring, writer advancement, workplace harassment, and bias among diverse writers, examining 282 working Hollywood writers who identify as women or nonbinary, LGBTQ, people of color, and/or people with disabilities, analyzing how they fare within the writers’ room. In positions that range from staff writer to executive story editor, a nearly two thirds majority of this surveyed group reported troubling instances of bias, discrimination, and/or harassment by members of their individual writing staff. Also, 58 percent of them said they experienced pushback when pitching a non-stereotypical diverse character or storyline; 58 percent later experienced micro-aggressions in-house. The biggest slap in the face: When it comes to in-house pitches, 53 percent of this group’s ideas were rejected, only to have white writers pitch exactly the same idea a few minutes later and get accepted. Other key findings from the report: 58 percent say their agents pitch them to shows by highlighting their “otherness,” and 15 percent reported they took a demotion just to get a staff job.

But there was more: 65 percent of people of color in the survey reported being the only one in their writers’ room, and 34 percent of the women and nonbinary writers reported being the only woman or nonbinary member of their writing staff; 38 percent of writers with disabilities reported being the only one, and 68 percent of LGBTQ writers reported being the only one.

For Dominic Taylor, the lack of diversity and inclusion in TV writers’ rooms can be fought in part by opening up the curriculum on college campuses, which he has expanded since joining the faculty at UCLA. “Students need a comprehensive education,” Taylor pointed out. He noted the importance of prospective playwrights being as familiar with Migdalia Cruz, Maria Irene Fornés, James Yoshimura, Julia Cho, and William Yellow Robe as they are with William Shakespeare, and looking at traditions as vast as the Gelede Festival, the Egungun Festival, Shang theatre of China, as well as the Passion Plays of Ancient Egypt.

“All of these modes of performance predate the Greek theatre, which is the starting point for much of theatre history,” explained Taylor. “It is part of my mandate as an educator to complete the education of my students. Inclusion is crucial to that education.”

After all, with the growing variety of platforms for story and expression, why shouldn’t there also be diversity of forms and voices? Whatever the medium of delivery, these are trends worth keeping an eye on.

Marcus Scott is a New York City-based playwright, musical writer, and journalist. He’s written for Elle, Essence, Out, and Playbill, among other publications.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Yuri!!! on ICE” Comments on Music by Music Production Team!

TV anime “Yuri!!! on ICE” is enhancing its wonderfulness with many pieces of music. We have interviewed music producer Keisuke Tominaga (PIANO), compositor Taro Umebayashi and Taku Matsushiba to hear about their music’s attractiveness and secret stories of producing them. We are now introducing some comments which could not be on PASH! for January on PASH! PLUS! Let’s start the first half!

Keisuke Tominaga Born in 1978, place of birth is Yokohama. Music producer. Graduated from photography course, Nihon University College of art. After retiring music production GRANDFUNK, established PIANO inc. in 2012. Representative director. Interested in sea fishing. Principal products are TV anime series “Terror in Resonance”, “Space☆Dandy” and “Kids on the Slope”.

Taro Umebayashi Born in 1980, place of birth is Tokyo. Songwriter and music compositor. Graduated from Faculty of Music, Tokyo University of the Arts and studied songwriting and orchestral music. Released 1st album “greeting for the sleeping seeds” from Rallye Lable as an artist [milk].

Taku Matsushiba Born in 1991, place of birth is Osaka. Songwriter and musician. After graduating from The Music High School Attached to the Faculty of Music, Tokyo University of the Arts, studied at Faculty of Music, Tokyo University of the Arts and completed master’s course of songwriting. Mainly analyzing and performing contemporary music, but widely committing to such as orchestration and commercial music by using his conduction skill.

・Victor Nikiforov FS “Aria <Hanarezu ni Soba ni Ite>” (3:41) Conducted by Taku Matsushiba, Ensemble FOVE (Tenor: Kazuma Kudo)

Q.What is ‘Ensemble FOVE’, which is precipitating in many pieces of music?

Ensemble FOVE is an up-and-coming ensemble by one of the most outstanding musicians of classics and contemporary music. We have asked them to perform some pieces of music which even are not credited in “Yuri!!! on Ice” (for example, orchestra part of “History Maker” is one of them). I think the most impressive parts of “Aria <Hanarezu ni Soba ni Ite>” are solo part of cor anglais by Kanami Araki and performance of harp by Rino Kageyama. Adding to that, upsurge of tutti in the middle part of the music might be one of the most attractive parts in this ensemble. (Matsushiba)

The wonderfulness of group composition in Ensemble FOVE can be seen in credits of soundtrack “Oh! Suketora!!!”. This classical song we made was recorded in big studio with conduction of Mr. Matsushiba with full orchestra to make it sound like real concert. We had to take a risk of not being able to retake the individual parts, but we could record the resonance and ambience of instruments, so I think the music became rich in sound. This music became such a good product by the work of Mr. Hiroaki Sato, who was the recording engineer for all the pieces of music. We have talked to make this piece of music ‘as if you are listening at special seats in concert hall’, so we used wide dynamic ranges of sounds.

Yuri Katsuki SP “Ai ni Tsuite ~Eros~” (2:16) Taku Matsushiba featuring Jin Oki

Q.Tell us the episode about making 2 different arranged pieces of music, “Ai ni Tsuite ~Eros~” and “Ai ni Tsuite ~Agape~”.

I first finished demo tape for “Ai ni Tsuite ~Agape~”, which was the part Mr. Umebayashi in charge of, and I listened to its melody part to make the arrangement version of “Ai ni Tsuite ~Eros~” with Mr. Matsushiba.

In “Ai ni Tsuite ~Eros~”, we featured interplay and descarga (*plays in ad lib). To make this happen, I thought putting musicians together and recording at same time will make a hot and powerful music. Since I decided this at primary stage, the recording was in form. However, we couldn’t get agreement from producer Yamamoto. I think the reason was ‘the music was too powerful’ or something. First, I was worried to rearrange the music, but by listening to it again made me to feel that the tempo was too thrilling and it was ‘passive’ rather than ‘erotic’. So I slowed down the tempo and showed the music to Mr. Yamamoto, this time he has agreed to the arrangement. By re-recording the music with slower tempo, I could feel the plays between the sounds and palma of flamenco. This made the music really erotic. But even slowing it down will make the eroticism to be old age (laugh), so we stopped slowing down just before that to be able to feel the youngness and passion of Yuri.

Yuri Katsuki FS “Yuri on ICE” (3:42) Taro Umebayashi

From the characteristic of Yuri made by producer Yamamoto and Ms. Kubo Mitsurō, and examining the meaning of a line ‘I will call this feeling love’, I talked with Mr. Umebayashi to adjust the image of Yuri that “so many memories of ‘love’ came and went through in his life”. The sounds of piano circles around to develop the emotion of going through in his memory, the rhythm carries the atmosphere, and suddenly it breaks (*the music stops) in the middle part. The climax gains the groove and the hot emotion melts and flows towards finale.

The melody and phrases which Mr. Umebayashi came up with were great. When I was working on pre-pro (*some work to be done before recording) with an image of Yuri sliding on the ice with its rhythm, there were some moments that I strangely, but naturally, felt like I made this song. By the way, in episode4, there is a scene when Yuri was listening to demo music which his friend made, but actually the music played at that scene is the 1stdemo we made. You can see that the code progression and rhythm were fairly completed at that time.

Yuri Plisetsky SP “Ai ni Tsuite ~Agape~” (2:20) Taro Umebayashi

After I finished making the melody part, I wrote the lyric in Japanese and sent it to Mr. Tokuya Miyagi (professor in Waseda University) to translate it into Latin. However, this work was extremely difficult. I was ignorant about Latin so I asked help to Mr. Matsushiba and visited Waseda University for several times, but it turned out that Latin was a language which we had to stick to its accent, which meant to us that we had to change the melody part of the music to make it sense. Then, the music team asked us that they have to consult the score division and the way of putting the word correctly to someone who has great knowledge of Latin. So, we visited Mr. Hidehiko Hinohara, who is a former teacher of Mr. Matsushiba and a songwriter with great knowledge of Italian. We asked him to correct the lines in both accent and musical ways, and went back to Waseda University to get re-checked with its lyric. We had to do this for several times to finish the work. Mr. Matsushiba helped me a lot during the progress, but when we were eating lunch at Waseda University after the meeting, he started to regret himself that ‘I can’t call myself a songwriter without knowing Latin!’ so I calmed him down by saying ‘I-I think you were doing great’ (laugh).

Yuri Plisetsky FS “”Piano concerto in B minor: Allegro Appassionato” (3:47) Conducted by Taku Matsushiba, Ensemble FOVE (Piano: Kaoru Jitsukawa)

The performances of Mr. Matsushiba’s conduction, Mr. Kaoru’s elegant piano, Ensemble FOVE’s strings, brass, wooden pipe and percussion were soulful and wonderful. I could tell that the members of Ensemble FOVE are really in high level, which they were playing Mr. Matsushiba’s difficult scores very easily. I personally recorded this type of classical music with live performance for the first time. And its newly written score… this isn’t a normal thing to happen. I was really excited when I was editing this music to the scene of Yurio’s skating (episode 9 & 12).

Kenjirō Minami FS “Minami’s Boogie” (3:32) Taro Umebayashi

The songwrite and electric guitar is by Mr. Umebayashi himself. Brass-arrange was done by Yoichi Murata, who is well known with ‘SOLID BRASS’ and a representative trombonist in Japan. The music became really entertaining but powerful and explicit with perfect brass-arrange.

I was glad to see the high-spirited choreography with a performance of air guitar by choreographer Kenji Miyamoto.

I went to watch the “Christmas on Ice” to study figure skating, but it was my first time of watching an ice show, so I tried hard to get tickets. I logged in to the ticket page really fast, but tickets were sold out immediately. I was surprised by the popularity of figure skate, and when I was about to giving up, producer Yamamoto told me ‘I got a ticket from my friend’ and he gave me the ticket. I thought Mr. Yamamoto was a great person at that moment.

Phichit Chulanont SP “’Shall We Skate?’ from a movie Osama to Skater (The King and the Skater)” (2:15) Taku Matsushiba featuring The Soulmatics

The main vocal and chorus were done by a gospel group The Soulmatics. They well knew the sound images of Broadway, Disney, “glee” and more, so they grasp the point of what we were wanting. Also, some of the members were trained at New York, which made the recording to be done without hesitation. When we were recoding the background chatter, they casted themselves as the King, vassals, gatekeeper, town girl, drunker and more to make the atmosphere of the session, which was really fun.

The sounds hear like a live performance, but most of the sounds were made by sampling and step recording. This is done by Plus-tech Squeeze Box, alias Tomonori Hayashibe, who has nicknamed ‘the magician of sampling’. He is a genius of making any sounds with computer programs, and Disney-ish, musical-ish, cartoon-ish music are his fields of expertise. He exhibited his full power to this piece of music. Some other music, even non-programed music are arranged by Mr. Hayashibe in “Yuri!!! on ICE”. This is about an another anime, but the 17thepisode in “Space☆Dandy”(Produced by Shinichiro Watanabe) is all about musical and all the music are made by Mr. Umebayashi and Mr. Hayashibe. This episode is well-made and really laughable, so if you are interested, please watch it.

Phichit Chulanont FS “’Terra Incognita’ from a movie Osama to Skater 2 (The King and the Skater 2)” (3:41) Taku Matsushiba featuring U-zhaan

This is a hybrid world music which is a mixture of BBflute, bansuri, tabla and sitar in live performance, bagpipes, electric guitar, synthesizer, step recording and Bulgarian-ish chorus. I personally love this music because the balance of groove went perfect, without being chaotic atmosphere. ‘Bansuri’ is an Indian instrument which has a similar sound to Shakuhachi (Japanese banboo flute) and it was performed by Junichiro Taku who performed flute sound in the music of “Yuri!!! on ICE”. He has the power to express the scene with his performance, so recording with him was really fun. I cooperated with Mr. Taku in some other animations such as “Terror in Resonance” which I made the background music with Yoko Kanno (further comments about this are below). ‘Tabla’ was performed by U-Zhaan and ‘sitar’ was performed by Daikichi Yoshida. They are both top players in Japan. Some other pieces of music, such as music used in trailers are made with cooperation of U-zhaan with his great performance.

Q.What are the meaning and language used in this music as lyrics?

I imaged an archaism of which used in an imperial ruled country in ancient Asia, but to be honest, it means nothing. I first finished with melody and chose some words which enhance the melody. This way of choosing words were like vocalizing (* way of singing with vowels but without lyrics). I chose these words with Mr. Matsushiba while vocalist Tomoko Koda was recording. These techniques are influenced by Yoko Kanno when we were working together. Way of breathing, directing, producing, strength and weakness and all the other things needed for making music are taught by her.

Guang-Hong Ji SP “La Parfum de Fleurs” (2:05) Conducted by Taku Matsushiba, Ensemble FOVE

Ami Ito (Ensemble FOVE) is performing the solo part with violin, but the way of performing is like a Chinese fiddle, to be concentrated on vibrato. The first impression of this music might be an easy-listening and beautiful, but in reality, this is a curious music but has romantic atmosphere. I really love this. (Matsushiba)

Guang-Hong Ji FS “’The Inferno’ from a movie Shanghai Blade” (3:43) Taku Matsushiba

The orchestra part of this music was done by Ensemble FOVE and other beat arrangement and SE/ME works were done by beat arranger Nozomu Yoneda. First half of the part is in six-eight time and it changes to quadruple time after the car chasing. It was especially hard to make the atmosphere of speeding with six-eight time, but it succeeded with a help of Mr. Yoneda. The wonderful performance of sax was done by Kohei Ueno with a scene of “abduction and confinement”. Actually, it’s hard to discover, but the sound effect of running car is used in the music (laugh).

The order was to make the music sound like ‘Chinese mafia’, so I was peering the poster of a movie “Infernal Affairs” and fantasized its sound tracks while making the music (but actually, I haven’t watched it yet). The sound of sax by Mr. Ueno is rude and erotic. I think I was keep saying ‘more erotic!’ for all the time while I was making music.

+ FIRST HALF +

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a Music Producer? Culture Club Producer Steve Levine Explains

What is a Music Producer? Culture Club Producer Steve Levine Explains: via LANDR Blog

Every musical project is the result of a group of collaborators working together.

Even when the artist is the star of the show, there’s always a handful of skilled professionals to support their vision and make it work.

Behind the scenes you’ll find mix engineers, session musicians and most importantly, producers.

But the producer’s role is one of the most frequently misunderstood in music.

One person who knows the producer’s craft inside out is Steve Levine. He’s known as the producer behind Culture Club’s massive 80s singles and the only person other than Brian Wilson to produce the Beach Boys.

We sat down with Steve to talk process, collaboration and the core of the producer’s role.

In this article you’ll learn what a producer is and find out how connecting with one can make a difference in your music.

Let’s get started.

What is a producer in music?

A music producer can have several different roles depending on the genre of music and type of workflow.

In the traditional recording process, a music producer acts in a similar way to the director of a film.

“A film director decides the location, the actors and cameras the same way a music producer chooses the instrumentation, musicians, or recording gear”

They create a vision for the material and advise the musicians artistically on how to achieve it. During a recording session the producer acts as a coordinator and provides organizational help. They also offer creative input and notes on the musicians’ delivery and the technical choices made by the engineer.

Producers often have skills and experience in all the different phases in the life cycle of a song. That means that they can make contributions on everything from songwriting details to equipment choices and delivery notes.

After the sessions, the producer provides feedback and direction during the mixing and mastering stages to ensure that the musical vision they’ve created with the artist gets realized.

“Historically, the reason we were called producers rather than directors goes back beginning of rock’n’roll with people like Sam Phillips. The early creators of music acted as studio owner, sound engineer, mastering engineer and the physical producer of the record as well. That’s where the title came from—those very early pioneer rock’n’roll days where the person that ran the session was the central hub.”

What does a producer do in a session?

Facilitating creative relationships is the core of a music producer’s work. Most of it happens during the session itself.

On a recording date, the producer has to organize and direct everyone on the project to keep things running smoothly.

Getting good results from a diverse group of people in a high pressure environment with the clock ticking on an expensive session is an art. For Levine, the key to success is a solid foundation of good social skills.

Good people skills are what separates the wheat from the chaff. 80% of the job is dealing with people and 20% is the technical part. We can all buy the same gear—to a certain degree—but how we use that gear and how we communicate with artists is what sets successful producers apart.

Maintaining these sometimes delicate interpersonal dynamics while still keeping an eye on the technical details is a balancing act. At the end of the day, the producer has to deliver solid tracks to the mix engineer to make the project a success.

Every session is unique, but Levine maintains that the most stubborn technical issues a producer encounters are common across many types of music. Experience, intuition and strong instincts are what it takes to overcome it.

For Levine, that experience is the key ingredient for a successful session.

“Most of the problems that sessions encounter are the same regardless of genre. The same technical problems could happen on a hip-hop track or an indie track on a folk track or even a jazz track. A producer that can manage those problems doesn’t necessarily have to be pigeonholed in one genre.”

“When a session goes smoothly, it’s like a swan gliding across a pond. It takes a lot of experience to get to that level. When things go wrong you start to see how much experience matters.”

An evolving role

The producer���s role continues to evolve with modern developments in music.

In R&B and hip-hop, the term producer most often refers to the person who created the beat the artists are singing or rapping over. In EDM the words “producer” and “artist” are often used interchangeably, with most artists producing their own material.

Levine has seen these developments first hand as music production work becomes more distributed and accessible.’

“Today it’s not unusual to have a producer that just does the beats or vocals on a track. A studio might produce the backing track with one team of people, a top line would be written and someone else would produce the vocals. And of course in the dance world the producer might have had nothing to do with the original sessions whatsoever. They act as a remixer and could do anything from adding new drum tracks to reinventing the whole thing.”

Collaboration and results

No matter what genre you work in, productive sessions are a team effort.

Bringing out everyone’s best work and playing each collaborator to their strong points is crucial for a producer.

As Levine is quick to note, each contributor has strengths and weaknesses. It’s up to the producer to recognize them and act accordingly.

That mix of factors can make the end result pretty unpredictable. Even with the best intentions and preparation, not every set of collaborators are perfectly matched.

“It’s impossible to be a master of every discipline in music. As a producer, collaboration is still something that I really champion—even if it’s virtual. Someone else can reinterpret your ideas or bring something to the party that you haven’t even thought of. That’s extremely valuable.”

No one sits down and says, “let’s make the worst record we possibly can!” Most people want to create their best work from the start, but so many things can weigh on a project—lack of money, lack of time, lack of talent… “

That’s why connecting with the right people is just as important as any other phase in the development of a song. Choosing the right producer is no different. LANDR Network connects you with top tier producers who know how to get the job done.

Be adaptable

A great producer has to stay focused on the human element, but there’s no substitute for solid technical skills.

For Levine, the development of technology and music production are deeply intertwined.

But the changes brought about by modern tech aren’t limited to developments like DAWs and VST plugins.

“I’m one of the group of producers who had their success during the massive change in technology in the 1980s. I had to navigate the switch from analog tape machines to digital recording and analog synthesizers to digital synthesizers—with all the processes involved there. Many of the producers of my era grew up with technological change so modern tech is second nature.”

Technology is changing the fabric of collaboration itself, and producers need to be ready.

As more and more work moves online, marketplaces like LANDR Network are carving out a space in the conversation.

“Until now there hasn’t really been a home for professional work online. There are plenty of places where people can exchange ideas, but the quality isn’t always there. I think now the opportunities are much greater.”

For Levine, it’s about creating a hub for trust and quality.

Network is where top tier talent and aspiring artists collide, levelling a playing field that was once restricted by gatekeepers.

The post What is a Music Producer? Culture Club Producer Steve Levine Explains appeared first on LANDR Blog.

from LANDR Blog https://blog.landr.com/what-is-a-music-producer-steve-levine/ via https://www.youtube.com/user/corporatethief/playlists from Steve Hart https://stevehartcom.tumblr.com/post/623808915910590465

0 notes

Text

The 1st Funding Proposal I worked on and wrote...

Funding proposal for the Start with Art Project

Objectives of the Start with Art Project

To enable up to 100 young people in care in, aged 8 -16, to participate in art workshops based in their residential children’s units in Glasgow. Professional artists, trained in working with care experienced young people, will run the workshops and enable young people to gain confidence and better self-esteem.

About Articulate

Established in 2016, Articulate’s vision is to fill the gap in the national arts education landscape with provision designed and delivered inclusively with our beneficiaries at the heart and helm of our endeavour.

Articulate aims to positively impact on the life choices and chances of care experienced young people by helping to unlock their creative potential; using artistic processes and practices. We aim to support them to feel empowered to recognise and claim a creative and cultural identity and to make positive progress in learning, in life and in preparation for the world of work, where the value of creativity is on the rise in the predicted workforce of the future.

The Need

Every year Government spends vast sums in the care system and yet the 15,000 Scottish children and young people in residential, kinship or foster care still have:

• High rates of suicide

• Poor mental health and physical well-being

• High rates of teenage pregnancy

• Poorer access to continuing and higher education or training

• High unemployment and homelessness

• Higher chance of being incarcerated

These young Scots, through no fault of their own, have some of the worst social, emotional, educational and economic outcomes in the country.

On the other hand, the creative industries are on an upward spiral of growth, buoyancy and are anticipating skills shortages in key areas. It’s a regularly quoted statistic that 60% of the jobs our children will be doing in 2030 have not yet been invented. We also anticipate that, due to digitisation, a disproportionate number of jobs realised will be in the creative industries and 87% of these new jobs will be at low or no risk of automation, compared with 40% of jobs in the UK workforce as a whole (Bakhshi et al, 2015).

Children’s residential houses in Glasgow were consulted in 2017 about their need for and confidence to deliver creative activity for the young people in the care of the city. Almost all staff consulted confirmed that they knew their young people would benefit but had little idea where or how to start, how to signpost interest or talent, or how to generate or develop creative ideas. Start with Art aims to enable young people in care to overcome these barriers and to help them tap into their huge capacity for creativity and artistic expression.

The Project

The first year of the Start with Art project (2017/18) concentrated on providing a framework for art activities in residential units. Working primarily with training the residential care staff, Start with Art sought to establish the where, how and why of doing art workshops in these residential units. During this year the Start with Art project was able to fund storage units for art materials for each of the 18 residential children’s homes in Glasgow. These storage units and materials brought a completely new resource into these homes, one which previously had not existed. Managers in some residential units began to buy more art materials to top-up those provided by Start with Art. During this first year of working with residential staff, some units identified a time of day - just before dinner - as a key time in which to come together and be creative, and many staff have come to understand the benefits of doing art activities at the kitchen table, where mess can be encouraged!

All the children's residential units have now established a safe space in which young people can create, experiment and play with art materials. This meant that young people now had a shared space in which they can find respite, solace and encouragement, and ultimately making the units more fun and creative places and spaces.

In the second year of the project (2018/19), 17 of the 18 residential units took up the offer of an art workshop and the artist worked directly with the young people. 59 young people engaged throughout the year. Many of these young people were keen to do more and we knew that this is a model of work that we can expand. Lead artist Jenny Hunter said,

“For 2020 it would be good to work over longer periods of time with some units, rather than just one- off workshops. In some places the young people are desperate to do artwork and ask when I am coming back. They would love more engagement with creative people.”

Now, for 2020, we want to build on the success of the project so far and expand the number of workshops offered to young people in each unit. In 2020 we will work with 10 residential units and offer each a series of 6 workshops across the year. The 2020 project will also offer a one year art workshop apprenticeship to one young person with very recent or current experience of living in care. This young person will help deliver the art workshops alongside the professional artists.

All the young people involved in the project will be consulted at the outset about what they would like to create during the workshops at their unit. They will also be asked to feedback on the workshops produced and on new ideas for workshops as they emerge, through the course of the year. Previous year’s workshops have included, printmaking, animation, comic creation, photography, graffiti art, willow weaving, and marbling with inks amongst many other things.

Start with Art will also facilitate exhibitions of the art work made by the young people. In 2018/19, an exhibition was mounted in the window of the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration office in Bell Street, Glasgow, with great success. Jennifer Orren, Participation Officer told us, “The feedback has been amazing and people are stopping daily to look at the display and admire it!”

Benefits and Outcomes

Young people in care all experience barriers to accessing and participating in art activities. But through the Start with Art programme we hope to break these down. Start with Art will use the proven benefits of arts participation to influence the life choices and chances of care experienced young people by providing visual arts workshops to build confidence and improve creativity. Between April 2020-April 2021 it is expected that:

· 10 residential children’s units in Glasgow will have each hosted 6 art workshops by professional artists for young people in care

· 75-100 young people will have increased confidence, self-esteem and learned creative skills

· 1 care experienced young person will have had the opportunity of a paid apprenticeship as an arts workshop assistant.

What Young People Say

“I was first introduced to Articulate through my past social worker, who told me how I'd benefit from being a part of Articulate. The highlight of my time working with them was getting the chance to have experiences that I wouldn’t have had before. Drawing is my passion - I have a love for storytelling, and I'm planning on working in the animation industry, doing some work in comics and eventually going freelance.”

Wali

“I first became involved with Articulate 2 years ago. They were running a photography project - it was right up my street at the time. In the 2 years working with Articulate the highlight has definitely been meeting everyone. I have met talented artists, people who inspire me daily and friends for life. I’ve learned so much from them and I hope they have learned something from me as well.”

Nicole

What Our Supporters Say

“Start with Art has been a valuable programme in relation to bringing creative practices to children living in Glasgow’s Residential Homes. By engaging and bringing news skills to residential staff through their art training workshops, Articulate have succeeded in tackling one of the major barriers. Staff within residential units are the gatekeepers to accessing new experiences - and if they lack confidence in the use of creative modes of engagement this can result in young people missing out. Staff have actively engaged and delighted in their own creative development and have transferred these skills to the young people. Supplying materials and on-going in house workshops has built on the interest raised and we would welcome a continuation of this approach”

Clare Macaulay, Social Work Department, Arts in the City project, Glasgow City Council

0 notes

Text

The Art of Reading Indie

Can anyone be beautiful if someone doesn’t say to them, “I think you’re beautiful”? Can anyone be intelligent if the results of a test don’t confirm: “you’re a genius”? And more pertinent to our discussion, can any book be good if not validated by a 4 or 5 star review? Can a book without reviews at all be good in any sense of the word? Doesn’t someone need to tell us it is? Otherwise, isn’t beauty, intelligence, and artistic worth a relative term, utterly meaningless without a verifiable source?

When you browse the shelves of a bookstore or library, you implicitly know that these books have been curated for you by the experts. Not only publishers, but booksellers, sales charts, award committees, and librarians have each had their say, and personally picked through the debris of literature to offer these chosen gems: these are good and worth your time, they seem to say. So even if you take a book and decide it’s not for you, the reason isn’t that the book itself is bad, or comes from an inferior pen; it simply wasn’t your cup of tea, or what you were in the mood for. You don’t take it personally (or most of us don’t).

The same certainly isn’t true for an indie writer, whose book is usually curated by the writer’s discretion alone. Such a book has no publisher or librarian standing behind it; it merely says why not give me a chance? But there’s no guarantee that if will be well-written. It may even be ungrammatical. Chapters might break off without development. Characters might be crude caricatures, dialogue a mannequin’s attempt at small talk. The story might betray its origins as a half-baked excuse for conflict. It might outstay its welcome by the second chapter. For these reasons and many more, some readers avoid them entirely, or at least approach them with considerable skepticism. Why read indie books when there are thousands—millions!—of properly curated books waiting to be found?

Perhaps the answer lies in those very “millions.” If there are millions of curated books, each one backed by a publishing company or an agent, can every one of those millions be a unique work of art? To have a publishing industry, in fact, you not only need a standardized measure of quality, but a product. In short, you have to produce many of the same kinds of books on a predictable schedule. If every book tried something new or innovative, the industry would falter. Money would be lost. Careers would go down the drain. In point of fact, doesn’t it take someone coming from the outside—an indie, so to speak—to reinvent the wheel? (and in art, the wheel could always run a little smoother).

Indie books have the potential to be true game changers in the industry. They don’t have to follow market trends; they don’t have to play by established rules; they can mimic old forms while boldly striving for something new; and most of all, they can question common sense advice about what makes writing and stories “good”. A team of gatekeepers, from agents to editors to CEOs will all have an opinion on this and will make sure a given book conforms to these models. Not that these people are Philistines with no taste…but they do have to make money. An indie writer would love to make money, too, but he/she (probably) has another source of income. His or her entire income probably isn’t riding on the success or failure of this novel (and if it is, maybe he/she should take up a more stable profession). The freedom of being able to publish a novel without scrutiny while following your own aesthetic leads to a classic Scylla and Charybdis situation: on one side, malicious indifference and anger to your ‘new’ book, and on the other, the chance of writing something slapdash that hasn’t undergone the proper vetting/editing process to make it worth reading.

And it’s true: so many indie books probably shouldn’t have been published. The authors might not have the skills or the patience to write a good book; or they might possess these talents, but the enticement of publishing on demand tempted them to release a product too quickly, selling a glorified rough draft as a slick, $15.99 novel. Given these realities, should we, as readers, become the gatekeepers these authors avoided? Should we read them with dark brows and clicking tongue, lashing every spelling error and grammatical lapse? Should we really expect them to be the equal of traditionally published novels? And what penalty should we exact upon them when they fail to meet these expectations?

My answer to these questions are relatively simple: you have to read them differently. They’re not ‘normal’ books. Lest this sound condescending, consider that I, too, am an indie writer. And I honestly hope that readers don’t read my books like the latest bestseller (which is why I only charge the Amazon minimum for each one, 99 cents). I write books that follow many traditional hallmarks of the fantasy genre, but I’m also aware that I can re-write or re-fashion the rules on a whim. And so I do. I write the fantasy novels that Jane Austen might have written, which means (I think) that I try to look at a familiar genre from an unfamiliar perspective. I love old books, books that are two-hundred, three-hundred, even a thousand years old. But I also love where books have ended up, and what’s happening to them today. When I try to write books from both perspectives, agents and publishers tell me I’m wrong; we don’t write like that anymore, the kids won’t understand it, your writing is stiff and you use too much punctuation. In short, it’s not a product they can successfully market and curate on the shelves with their other ‘millions.’

That’s why I chose, at first reluctantly, but now by choice, to self-publish my novels. I want to mix and match, to bend and twist, to mold the fiction into a new shape that resembles (without mirroring) the books that I love. I want to take chances. And most importantly, I want to amuse myself. I don’t see a lot of joy and gusto in publishing today, largely because it’s become so safe and predictable. Indie writing doesn’t have to be safe or predictable. What they have to do is be themselves—not according to a formula, but according to the inner logic of the story itself.

Of course, that requires readers who are willing to follow along. Readers who don’t mind the occasional spelling mistake or story lapse, but who are willing to take the stories for what they are: bold experiments by lone visionaries who don’t have the backing of a major publishing house or team of editors and curators behind them. These are people pursuing a dream against all odds, and it’s a dream no one particularly wants them to follow. For that reason we need to read these books not like the next Steven King novel or the latest Neil Gaiman installment. Experience them like a strange new language, one that takes time to translate and to understand properly. And if, in the end, the story turns out to be a dud, to require more time to rebuild and reshape—what then?

That’s the unique beauty of indie writing: you can then tell the author. Communicate your concerns and misgivings to them rather than simply lobbing off another 1-star review. Don’t look at indie writing as a finished product. Rather, it allows you, the reader, to be a co-creator, an editor, a quality control expert. Chances are, the author is waiting desperately in the wings to hear something, anything, about his or her novel. And the chances are, your insights and criticisms will be like manna from heaven, reminding authors that someone is listening—someone is reading their work. A single good reader makes any writer, no matter how accomplished, a better one. So doesn’t it behoove us to read as many indie books as possible, to find the gems, and encourage these writers—good and bad—to ruthlessly pursue their art? For writing is an art first and foremost (sorry marketers!), and only artists will help us adapt it for the ideas and individuals of the 21st century.

�6�a�C�

0 notes