#like a person shaped rock with moss and lichen on it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Meat Forest

A story about a normal forest and it's normal bounty that I wrote earlier this year. It and others can be found in my substack.

There is an oddity known to few who live in safety in the towns and cities of civilization. The seemingly mythical place is less of a secret to those who live closer to it but no one is asking them and they’re not volunteering the information either. What is important to know is that all who know about the living sin, without council or collaboration, agree individually that this should be kept secret. Rarely if ever is it spoken about between two who are cursed with it’s knowledge, because to talk of it is to acknowledge to another living person that you both accept that something like it can and in fact does exist in this material world and not just in the lands of dreams.

This is the abhorrent ecosystem known simply as the Meat Forest. Some hidden occult texts once deciphered may call it Hell’s Larder, the Great Wet One, the ArborMeatum, Fleischwald or even the Growing Temple-Of-Earth’s-Flesh. But they all mean the one and only Meat Forest, a fleshy dark spot on the notions of natural world in the collective psyche. A sprawling place similar to the wild woods far from the hands of lumberjacks and human interference only that in single aspect is a recreation rendered in living apparently healthy flesh.

Tall bony trees; draping branches of fleshy leaves shading all below in a canopy of skin; open meadows of delicate grass-like feathers prickling up in goose bumps in the breeze; boulders of skin sporting soft, downy hair like mosses and lichen; sprawling vines of toothed tentacles tangled into thick brambles; and delicate orchids like blooming organs and open eyes. Somewhat confusedly the denizens that call the Meat Forest home share it’s odd configurations, creatures you would recognise as deer crested with proud antlers shaped like grasping human skeleton hands; in place of its pelt a skin like that of a new born baby. Hairless primates, their translucent skin displaying the riotous colours of their internal organs, swing hand over hand through the boughs of the bony trees searching for fruit reminiscent of human anatomy. A small hairy spider perches on a toughened web of extruded sinew and watches for prey with it’s eight upsettingly mammalian eyes. Even the tiny ants march to and fro, their carapaces gone, instead an army of little skin tags in the shape of an ant tend to their young and seek food. Interestingly the only creatures native to this land that resemble their non-meat forest counter parts are worms, they are still as squishy and wriggly as they ever were though some species are significantly larger and parasitise the land itself. Which brings us to the land itself: the meat forest doesn’t sit atop a top soil as would a natural wood. No, instead and unsurprisingly, it’s meat, seemingly as far down as a person could manage to dig before the hole filled with slowly seeping bright red blood. There is periflesh boundary to the forest; if one were so inclined you could walk out from the forest and watch as the flesh underneath becomes more interspersed with dirt and rocks until you were at its very edge and there you could, with some assistance, observe as little tendrily fingers groped their way through the grains of soil and slowly grew and thickened.

There are those who, despite the unspoken taboo, wish to actively engage with the Meat Forest and covet the smallest parts of it to keep as their own. It calls to them in their weakest moments like a bad friend who knows you’re vulnerable and wants to lead you to ruin. These people know it’s not to trifled with, best left alone and forgotten; that a vigorous walk followed by a nice quiche would be infinitely better than being shuttered away applying cypher after cypher to banned texts trying to glean just a little more information. Within that vanishingly small group of people in the know there’s a smaller cohort, those who have managed to touch a fraction of the bounty.

Some years ago, during a gruelling drought that gripped the continent, parts of the meat forest were dried out and died, a swathe of bony trees, their leaves hanging limply in the harsh sunlight, crusted with sweat and oils from the dying marrow within their branches. A similar fate befell an oak stand nearby, though it had succumbed much sooner, and one day as luck would have it a bolt of lighting obilerated an oak tree exploding it in a hail of fire and thus the trees began to burn. Smoke blanketed the area as the lazy breeze did nothing to blow it away, only spread it around and put the finishing touches on the meaty leaves curing in the smoke. By sheer fluke a traveller had become lost in the smoke trying to navigate through the oak trees and encountered the charcuterie hanging like ripe fruit. Not knowing better and somewhat delirious with heat they picked bushel after bushel thinking they had come across a wood camp of some hunters preserving their kills. This misunderstanding only lasted a few days after the traveller was rescued from dehydration and revealed their haul to their benefactors who, appalled at this transgression, attempted to persuade the traveller to burn the meat to cinders and bury the ashes. They explained, as much as they were able and willing, the wicked blasphemy that was the unspoken forest. The confrontation grew heated as the traveller was suddenly unwilling to give up this miraculous haul. In the end there was violence and staggering off with a broken shoulder and new pony was the traveller. In time they made it home however they died shortly after and their bag of meats vanished.

For the better part of two years the depraved individuals with enough wealth or power to afford the insane cost would hunch over a small cooking fire with a grill and watch with shivering breath as the bacon danced and sizzled over the coals. Hearts pounding in their chests and their sweat hissing as it dripped on to the grill, they would experience a sensation akin to religious ecstasy as they took hold of the profane meat this focus of their desire. Any attempts at self discipline to savour and enjoy this sin for as long as possible evaporated. Their bodies told the story of their weakness, burns on their fingers from reaching in to directly touch the meat, blisters on their tongues and mouths deadening the flavours as the agonisingly hot grease burnt them as they bit into the rashers. The days that followed were hollow and cold, full of regret at rushing through a hurried and shameful morsel, despair that they did not experience it properly because of the burns on their tongues, impotent fury they did not have the means or ability to get more, for the price is just so steep. A deep soulful yearning for more, to know more about the place the brought this obscene delight into being.

Because of the nature of the crime, each sinner in this cabal knew nothing of the others, not even how many there were or how to contact the seller, known only as Them. They would come to you when they knew you had enough to barter with to obtain another serving. No one knew how They found who would be amenable but certainly no one publicly had spoken out about this sinister door-to-door delicatessen so presumably everyone who approached was interested and was interested in keeping quiet. Then one day it stopped.

The flesh had run out. There wasn’t that much to begin with and even with diligent slicing with the sharpest of blades there were only so many servings that could be stretched out. Enough money and power had changed hands to fund and run a small nation, but even with all that it still had run out. Some buyers, strung out and desperate, assumed the experience could be recreated with other sinisterly obtained meats and turned to cannibalism but this was not remotely the same. This eventually led to a number of executions and questions from society as to why several seemingly unconnected people had been caught committing such a depraved act, whilst those in the know learnt of the names of others sharing their predilection. More must be sought out for They so enjoyed the wealth and power it brought, and so a team was dispatched by Them. Ignorant of the pain that is to come and the spiritual damage that will be done to them, these happy and brave friends march out clutching a series of sealed orders and directions content with the assurances of their rich rewards upon their return and the incredible care and wealth given to their families in the mean time paid in trust.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love nature. I think nature is epic. I think as a whole nature is much better than people as a whole. Here’s what I mean. I just spent six days looking at nature. I drove from my home in the middle part of the Midwest to the southwest. (I drove through Kansas, a tiny bit of Oklahoma, a tiny bit of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado.) While I did exit the vehicle and take some pictures, mostly I drove...alone. It was great being alone because I could just focus on the things that I wanted to see. I didn’t have to worry about anyone else’s needs. I didn’t have to ask. I didn’t have to try to figure out if they lied about their answer. But I digress. I drove through plains, farmland, mountains, canyons, mesas, etc. Very little of my travel was on interstate highways, which was great. Two-lane blacktops put you in the middle of nature. National parks let you get up close and personal with nature. (I didn’t cuz it’s January. Also while I might drive around alone, I don’t think hiking alone is terribly smart.) But back to nature. I saw cactus, who traditionally like dry, warm areas, living next to moss or lichen, who traditionally love cool, wet places. (don’t @ me. I’m not a botanist.) They just hung out together like it was great. If a cactus-equivalent person and a moss-equivalent person lived in that close proximity, it’s quite possible that cops would be involved. Not in nature, though. In Zion National Park, there’s this amazing tunnel. It’s just over a mile long. The mountains on one side of the tunnel look completely different from the mountains on the other side. (Again don’t @ me...not a geologist either) You only need to be slightly observant to see how different the rocks that make up those portions of the same mountains look. How often is that a problem with humans?? The number of cool shapes that have been sculpted by wind and rain, over time is just amazing in this portion of the country. Monument Valley in Arizona is stunning as are all the other examples of mesas, buttes, and other formations that I saw on my trip. What do humans do when someone’s sculpture doesn’t exactly match the “norm?” The other really cool thing is the lighting that nature provides. For reasons, I got to see Zion National Park twice. Once on a cloudy, drizzly day and the next morning with clear skies. Every rock formation looked different in the different light. I had several spectacular sunsets which made landscapes even more amazing. The shadows and light flares that sunset brings add so much to the view. I took some pictures with my phone and shared with my friends. But so many of the cool things I saw happened because I paused long enough to let the light change. Humans don’t often pause long enough to let anything change.

0 notes

Text

Ecology

Ecology is the study of how organisms interact with each other, and their environment.

Population- A group of individuals of a single species living in 1 area who can interbreed and interact with each other

Community- All of the organisms living in one area

Ecosystem- All of the organisms and the abiotic factors with which they interact

Abiotic factors- Nonliving factors like temperature, weather, water, wind, rocks, and soil.

Biotic factors- The organisms with which an organism might react, like birds, insects, predators, and prey

Biosphere- The global ecosystem

Niche- What an organism eats, and needs to survive

Properties of Populations

Properties are defined by size, density, and dispersion.

Size

The total number of organisms in a population. Births, deaths, immigration, and emigration limit the size of the population.

Density

The number of individuals per unit area or volume. Density is an extremely hard property to calculate, so ecological scientists use sampling techniques and estimate the number of organisms living in an area. Marking and recapture is an example of one of these techniques.

Dispersion

Dispersion is the pattern of which individuals are spaced within the area. Clumped is the most common pattern of dispersion, for example, fish swim in schools. Some organisms, like specific plants, live in a uniform pattern. These plants secrete toxins that keep other plants within a certain distance from them. Random spacing happens when there are no attractions or repulsions.

Population Growth

All populations have biotic potential. The biotic potential is the maximum rate at which a population could increase given ideal conditions. Some factors that influence biotic potential are:

Age when reproduction begins

Life span during which the organism is able to reproduce

Number of reproductive periods

Number of offspring an organism can have at 1 time

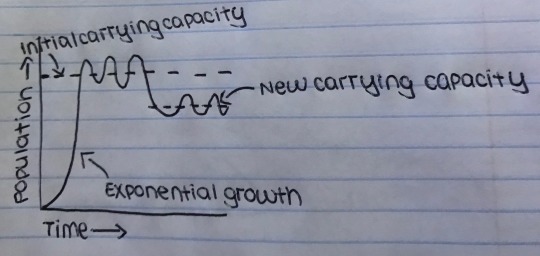

Some characteristics of growth are common with all organisms. Growth begins slow, then it explodes in a period known as exponential growth. Once the organisms reach carrying capacity, they will either become stable, rising and falling consistently or enter a death phase, where their population will crash. This may be caused by competition, waste, or predation, for example.

Fun fact: The human population has been in its exponential growth phase for 300 years.

The carrying capacity (K) is the limit to the number of individuals who can occupy an area at one time. Carrying capacity does not stay the same. It changes as environmental conditions change.

Reproductive Strategies

Organisms who are opportunistic, and reproduce rapidly when the environment is uncrowded and resources are plentiful are called r-strategists. Rodents are r-strategists.

K-strategists, however, do what they can to maximise their population size near the carrying capacity for the environment. Elephants and monkeys are K-strategists.

r-strategists have many small young, while K-strategists have few, large young

r-strategists provide little to no parenting, while K-strategists provide intensive parenting.

r-strategists mature rapidly, while K-strategists mature slowly

r-strategists reproduce once, while K-strategists reproduce many times.

Limiting Factors

Limiting factors limit population growth. There are two kinds:

Density-dependent factors: These are factors like competition for food, the buildup of waste, predation, and disease, that increase as the population increases

Density-independent factors: These are factors whose occurrence have nothing to do with the population size, such as earthquakes, storms, and volcanic eruptions.

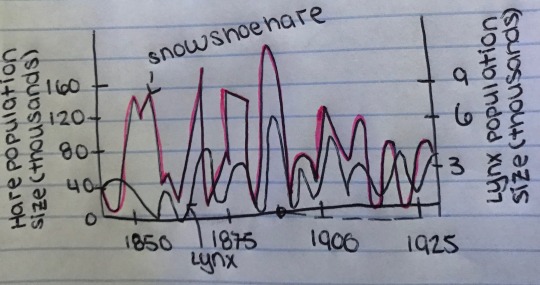

The Hare and Lynx Study

The Hare and Lynx study is a very famous study on population growth. It follows the population of snowshoe hares and lynx at the Hudson Bay Company from 1850 to 1930 and shows connected fluctuations between the two animals populations.

The Lynx’s cycle is caused by cyclical fluctuations in the hare’s population while the hare’s cycle is likely caused by the presence of resources

Community Structure and Population Interactions

There are 5 main categories of interaction: competition, predation, parasitism, mutualism, and commensalism.

Competition

G.F. Gause developed the competitive exclusion principle after he studied the effects of competition within a lab.

Gause studied the species Paramecium caudatum and Paramecium aurelia. When cultured separately, they both grew rapidly and levelled off at carrying capacity. When the cultures grew together. P.aurelia drove the other species to extinction. His conclusion was that: Two species cannot coexist if they share the same niche.

If two organisms share a niche in the same area, either 1 organism will be driven to extinction, or it will adapt to exploit different resources. This is known as resource partitioning.

Something similar to resource partitioning happened with the Galapagos finches. As they were isolated, adaptive radiation occurred, changing the shapes of their beaks so that they could exploit the most available resources. This divergence in adaptation is called character displacement

Predation

Predation either occurs when an animal eats another, or an animal eats a plant. Animals and plants have evolved defences like poison, and camouflage to avoid predation. Passive defences are characteristics like cryptic colouration and do not expend energy, while active defences, like fleeing or hiding, expend energy.

Aposematic colouration- Bright colouring found on poisonous animals warning predators to stay away

Batesian mimicry- When a harmless animal mimics the colouration of a poisonous one, such as the viceroy butterfly who looks similar to the monarch butterfly

Mullerian mimicry- When two or more poisonous species resemble each other to gain safety in numbers.

Feeding

Herbivores eat plants, carnivores eat meat, and detritivores are also known as scavengers. They are organisms like hyenas and vultures, who feed on the dead organic matter known as detritus

Mutualism

This is a symbiotic relationship where both participants benefit, such as bacteria in the human gut microbiome. The bacteria live in the intestine and produce vitamins that the host needs.

Commensalism

This is a symbiotic relationship where one organism benefits and one is neither helped nor harmed, for example, barnacles live on whales, giving them access to food. The whale is unbothered by their presence.

Parasitism

This is a symbiotic relationship where one organism benefits and one is harmed. Mosquitoes drink other animals blood. They get food, while the organism loses blood and an annoying allergic reaction that drives people crazy.

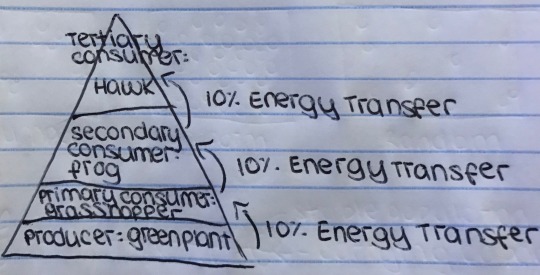

The Food Chain

The food chain is the pathway that energy is transferred from one trophic or feeding level to another. Only 10% of the energy from one trophic level is usable for the trophic level above it. So if at the beginning of the food chain, there is 1000g of plant matter (producers) the food chain can support 100g of primary consumers (herbivores) 10g of secondary consumers (carnivores) and 1g or tertiary consumers (carnivores)

In an environment, food chains link together to form complex food webs. Animals can occupy different trophic levels as a result. For example, when a person eats vegetables, they are a primary consumer, but when they eat steak, they are a tertiary consumer.

Producers

Producers are able to convert light energy into chemical bond energy. They have the greatest biomass of the trophic levels. They include plants, diatoms, and phytoplankton. Diatoms are photosynthetic algae that live in the ocean. Phytoplankton and diatoms make up the majority of producers in marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Primary Consumers

Primary consumers eat producers, and are herbivores, for example, grasshoppers and zooplankton

Secondary Consumers

Secondary consumers eat primary consumers and are carnivores. Frogs and small fish are secondary consumers.

Tertiary Consumers

Tertiary consumers eat secondary consumers and are at the top of the food chain. They have the least biomass and are the least stable trophic level. Some examples are hawks or sharks.

Energy and Productivity in Food Chains

Productivity is the rate at which organic matter is created by producers. Gross primary productivity is the amount of energy converted into chemical energy by photosynthesis per unit time in an ecosystem. Net primary productivity is the gross primary productivity minus the energy used by the primary producers for respiration.

Biological Magnification

Organisms in higher trophic levels have a greater concentration of accumulated toxins. This is called biological magnification. This nearly killed the bald eagle, due to a pesticide Americans were using in the 50s.

Decomposers

Not included in the pyramid are decomposers, usually bacteria and fungi who break down dead material so it can be used in the soil by plants. (It’s the circle of life)

Ecological Succession

Communities are not stable. Major and minor disturbances constantly cause fluctuations in population size. Sometimes, large disturbances, called blowouts like volcanic eruptions can completely destroy a community, or in some cases, a whole ecosystem. What follows is ecological succession. If the rebuilding takes place on an area where even the soil is gone, it is primary ecological succession, as the soil must be made first. The first organisms to live in a barren area are pioneer organisms. These are most often lichens. Lichens are symbionts made of algae and fungi, but also mosses, who arrive by spores. Grasses begin to grow, then bushes, and then trees.

When the soil is left intact, secondary succession will take place. This often happens after forest fires and is much faster.

Biomes

Biomes are large regions of the earth whose distribution depends on rainfall and temperature. Biomes are separated by these abiotic factors, but also by the vegetation and animals who live there.

Changes in altitude produce changes similar to changes in latitude. The Appalachian Mountains, and the Rockies, and coastal ranges in the west have similar trends in their biomes.

Marine

This biome is the largest. It covers 3/4 of earth’s surface

It is the most stable biome, with very little temperature fluctuation due to waters high specific heat.

Provides most of Earth’s food and oxygen

Subdivided into regions based on the sunlight they receive, distance from shore, water depth, and whether it is the open ocean or ocean bottom.

Open oceans are nutrient-poor

Tropical Rain Forest

Found near the equator with a lot of rainfall, stable temperatures, and high humidity

Cover 4% of Earth’s land surface and account for more than 20% of the earth’s net carbon fixation (food production)

It has the greatest species diversity. It has 50x the number of species of trees than a temperate forest.

Dominant trees form a dense canopy preventing rain from falling directly onto the forest floor.

Many trees are covered in epiphytes. These are photosynthetic plants that grow on other trees.

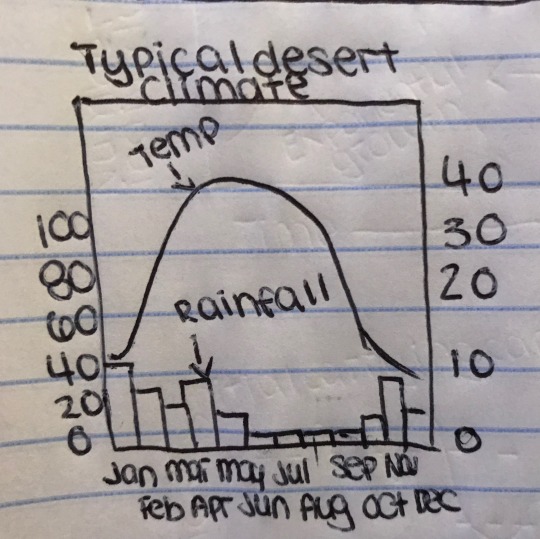

Desert

A desert receives less than 10 inches of rainfall per year and is too harsh for grass.

It experiences the greatest temperature fluctuations. During the day, the surface can be as hot as 70 degrees celsius, however, heat is rapidly lost at night.

Plants like cacti evolved shallow roots to collect as much water as possible.

Some plants evolved to grow only after hard rains. These plants will germinate, send up shoots and flowers, and die after a few weeks

Most desert animals are nocturnal or crepuscular. They burrow themselves or hide in the shade during the day.

A cacti’s spines are modified leaves.

Temperate Grasslands

Cover huge areas in both the temperate and tropical parts of the world

Low total annual rainfall, with the uneven seasonal occurrence of rain, preventing forests from growing.

Bison and antelope tend to live here.

Temperate Deciduous Forest

Found in the northeast of North America, south of the taiga. Trees here drop their leaves during the winter.

More plant variety than in the taiga

Has vertical stratification of plants and animals. Some live on the ground, some live on low branches, and some live in the treetops.

Rich soil because of decomposing leaf litter.

Conifer Forest-Taiga or Boreal Forest

Found in Northern Canada, much of Europe, and Russia

Dominated by conifer forests like spruce

The landscape is dotted with lakes, ponds, and bogs.

The abundance of rain, allowing trees to grow

Very cold winters

The largest terrestrial biome

Heavy snowfall, trees have downwards pointing branches to keep snow from acumulating

More species variety than in the tundra

Large temperature range

Tundra

Located in the far north of North America, Europe, and Asia

Called the permafrost, due to its permanently frozen subsoil in the farthest point north

Called the frozen desert, little to no rainfall

Appears to have gently rolling treeless plains with lakes, ponds, and bogs

Birds migrate during the winter

Low species diversity

Chemical Cycles

Water Cycle

Water evaporates from the earth, condenses to form clouds, then rains over the oceans and the land. Some of the rainwater percolates through the soil deeply enough that it enters a river or stream and returns to the sea. A lot of water evaporating from earth transpires from plants

The Carbon Cycle

Cell respiration by animals and bacterial decomposers add carbon dioxide to the air as a waste product.

When fossil fuels are burnt, they add carbon dioxide to the air as a byproduct

Photosynthesis uses carbon dioxide from the air and produces oxygen as a waste product.

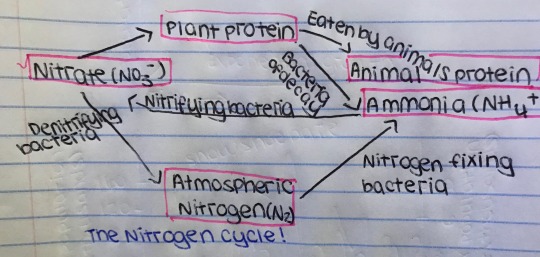

The Nitrogen Cycle

Very little nitrogen enters ecosystems directly from the air. Most comes as a result of bacteria.

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria live in the nodules of legumes and convert free Nitrogen (N2) into the ammonium ion (NH4+)

Nitrifying bacteria convert the ammonium ion (NH4+) into nitrites (NO2-) and then into nitrites (NO3-)

Denitrifying bacteria convert nitrates (NO3-) into free atmospheric nitrogen (N2)

Decomposers break down dead organic matter into ammonia (NH4+)

Humans and the Biosphere

As humanity has grown in size, we have begun to cause massive amounts of damage to the ecosystem. We deforest millions of acres of land, destroy wetlands, cause groundwater contamination and depletion, eliminate habitats, and have caused the extinction of countless species.

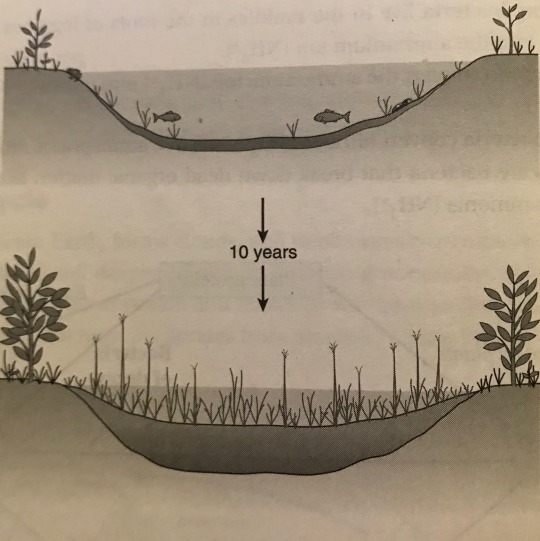

Eutrophication of Lakes

Eutrophication is caused by runoff from sewage and manure from pastures. These products increase the nutrients in the water, causing excessive growth of algae and other disruptive plants. Shallow areas become choked by the excess growth of weeds. This kills the photosynthetic organisms of the lake to die, reducing the depth of the lake and detrivores deplete oxygen in the lake as they break down the dead organisms. This vicious cycle continues until life in the lake has gone extinct.

Acid Rain

Acid rain is caused by pollutants in the air from fossil fuel combustion. Nitrogen and sulfur pollutants mix to create nitric, nitrous, and sulfuric acids which drops the pH of rain to around 5.6.

Toxins

Toxins from industry farming enter the food chain. Antibiotics found in beef and chicken have been found to have nasty effects on the people who eat them, as some may be carcinogens or teratogens.

Global Warming

Burning fossil fuels has released large amounts of CO2 into the air. This causes the greenhouse effect, where the excess carbon dioxide in the air absorbs the infrared radiation reflecting off of the earth, raising the average temperature. If the earth’s temperature were to increase by 1 degree, the polar ice caps would melt, causing mass flooding, massive weather fluctuations, and an increase in tropical storms.

Depleting the Ozone Layer

Our use of chlorofluorocarbons, which are chemicals used as refrigerants and in aerosol has created a hole in the ozone layer, allowing more UV radiation to enter the atmosphere, increasing the rate of skin cancer worldwide.

Introduction of Invasive Species

There are many cases where humans accidentally bring nonnative species to new environments. Because of their lack of predators, these species outcompete the native species, leading to massive consequences. For example, the African Honeybee was brought to Brazil in 1956, and have been making their way through the Americas. These bees managed to kill 10 people by 2000.

Pesticides v. Biological Control

Farmers use pesticides to keep pesticides from eating and ruining their crops. These chemicals increase food production, however, they may also be exposing humans to nasty carcinogens. It also causes the development of resistant strains of pests. Along with that, they travel up the trophic levels and may cause harm to species who are essential to their environment.

Biological control may be a safer alternative to pesticides. Some of these methods are crop rotation, introducing natural enemies of the pest, natural plant toxins instead of synthetic ones, and insect birth control.

#ecology#ecological science#ecology studyblr#studyblr#biology studyblr#biology#sat biology#sat subject tests#global warming#climate change#acid rain#ozone layer#invasive species#population#nitrogen cycle#water cyctle#carbon cycle

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro to Old Pepper Place

Hello all! I did some backtracking recently and wrote an introduction to Old Pepper Place starring Chloe Pepper, the person who sells the house to my girl Maya. I hope you like it!

The sun was at its midday zenith when Chloe Pepper stepped off the train. Not that she could see it. It was hidden behind a thick layer of clouds and had resigned itself to showering the ground with weak, watery rays. Her weathered hiking boots crunched on the gravel, wet from the rain that had peppered the windows of the Emerald Express for her entire ride. It was a passive, ambient sort of rain, best described by the phrase ‘there was rain’ because ‘it was raining’ sounds much too noticeable.

As the brilliant green and gold train chugged off behind her, Chloe began trudging toward the house. The path was slightly overgrown, and Chloe had to push past overhanging honeysuckle boughs to get through. After thoroughly soaking herself on the waterlogged branches, she took the last few steps and emerged in the front yard. The yard was even more overgrown than the path, but the house seemed just as it had on the many times Chloe had visited as a child. It was the same peeling paint, same haphazard layout, and same rickety front steps. But that’s not why she came.

Turning away from the house, Chloe set off into the woods. She’d walked these paths thousands of times before, and no longer needed the glow of stardust and the blanket of night to guide her way. The earth was soft underfoot, and her hiking boots left distinct boot-shaped imprints in the forest floor that quickly filled with water. Looking at the trail of puddles she was leaving behind, Chloe sighed, and thanked the stars that she didn’t care about being followed.

By now there was no doubt that her presence had been noticed. The rustlings in the trees and ferns behind her were undoubtedly dozens of creatures, curious as to where she was going, and why she’d returned after so many years. Reaching the Heart of the Forest, Chloe slowed her pace. She stood on the edge of the clearing for a second, drinking the place in. Oh, how she’d missed it. It was a clearing at the center of the forest, where the trees around the edges grew tallest and the moss on the ground grew thickest. In the clearing, moss mixed with grass and ferns to create a soft, intricate tapestry of greenery that made an almost perfect circle. Spring’s first flowers were beginning to sprout up around the Heart, snowdrops and crocuses adding bright pops of color to the otherwise emerald carpet. At the center of the clearing lay the Heart of the Forest, a hulking granite monolith, plopped in the middle of the woods by some long gone glacier. It was covered in moss and lichen, and worn smooth by years of weathering and tiny feet. A bell was nestled snugly into a nook on the side of the Heart, almost hidden by its moss bed.

Chloe took a deep breath and stepped into the clearing. She strode calmly and confidently, trying her best to hide her anxiety. Upon reaching the Heart, she grabbed the bell and clambered up the side of the rock. It was a feat she’d seen done many times, but one she herself had done only once before. Standing on the Heart of the Forest was a real experience. The sense of history that flowed through the rock was incredible. Chloe was overwhelmed just thinking about how many creatures had stood on this exact spot over the hundreds of years the forest had been here. She closed her eyes, breathed in the breeze as it played with her hair, and rang the bell.

The sound was just as Chloe remembered it. It was deeper than the size of the bell would make you believe, and it rang with an ancient tone that reverberated through the damp trunks and quivering leaves. The forest instantly sprang to life.

The rustling noises that had followed Chloe from the house stepped into the clearing, confirming her suspicions. But more creatures also came forth, scurrying, running, lumbering, and flying in from every direction. Grumpy owls blinked sleep from their eyes, perched on the highest branches of the surrounding trees. Squirrels leapt through the trees, stopping in the boughs of a particularly old maple to Chloe’s left. On the exact opposite side of the clearing stood the chipmunks, angrily tittering amongst themselves. Fairies flitted into the clearing on glowing wings, carefully settling down in the flowers and fiddleheads of the clearing. At this point in the year they were spring fairies, dressed in pastel greens, pinks, and blues. Out of the forest trundled their seasonal brethren, the hardy flower gnomes proudly showing off their trademark conical hats, wreathed in all the flowers they could find this early in the season. More and more creatures came, piling into clearing or standing halfheartedly at the forest’s edge. Chloe spotted a few trolls amongst the trees, and two forest guardians had also bothered to make an appearance. A number of spirits materialized from the morning steam and forest shadows, floating and gliding noiselessly among the gathered creatures. For a second, she could have sworn she saw the bark coated tail of a woad dragon swishing about in the rainy gloom.

When the majority of the forest’s residents had jostled their way into the clearing, Chloe began her speech.

“Hi everyone, long time no see.”

Dead silence.

“You’re probably wondering why I’m here.”

Dead silence.

“Ok, maybe not then. I’m going to tell you anyway.” A squirrel tittered. Chloe glared at it. “I’m here because we sold the house.”

The crowd erupted into noise. The trolls grumbled, the fairies chirped, the gnomes yelled, the spirits stayed silent, and one of the forest guardians walked away.

Not entirely sure of what to do, Chloe waved her arms about wildly and yelled “Settle down, settle down. You all knew this was coming. My grandparents have been gone for over a year now. This was inevitable.”

A particularly snotty gnome piped up. “Why does anyone have to live in the house at all?”

Chloe gave him a look that could have shattered glass. “You know just as well as I do that someone always needs to be in Old Pepper Place. There’s far too many secrets lying in that house to let it fall to ruin. And besides, the forest needs a problem solver.”

“But why does it have to be a human?” This time it was a rock golem, calling in its gravelly voice from beneath a poplar tree.

Chloe bit her lip. “Humans are the best at problem solving. We may not be the best at…other things-”

“Like caring about anything but yourselves.” The remaining forest guardian had spoken up, always happy to guard the forest with the power of snark.

Chloe shot it another glare and continued with a new edge to her voice. “Look, you all know me. And you’ve known my family for centuries. We’ve always helped the forest. We’ve always helped all of you. And the new person will do the same. But you will have to treat her kindly, and maybe help her out a little if she needs it. It’s going to be a steep learning curve.”

There was mixed grumbling from the audience, but nobody seemed to have a real problem with anything Chloe had said. She began to climb off the Heart. As she jumped onto the springy ground, a troll rumbled off a question. “So who is this new person?”

Chloe grimaced, and sped up her walk off into the woods. Over her shoulder she called “I’m not entirely sure, someone I sold it to online. She seems nice enough.”

The crowd was immediately riled up again, and the cacophony of voices rose up out of the clearing. Chloe, however, was already gone. She slipped off into the woods, but instead of heading back to the house or the train tracks, she found her way to what was usually a dried up creek bed. Today though, a thin stream of water trickled through, birthed by the morning’s rain. She followed the creek bed through the forest, the damp stones clacking under her feet all the way.

After about half an hour of walking beneath the sunlit treetops and towering ferns that grew from the dusty banks, the vegetation opened up to reveal Chloe’s destination. It was a lake, grey as the sky. Birches and poplars crowded its banks, their leaves shimmering in the stiff breeze that swept over the valley’s leafy ceiling. A dozen yards to Chloe’s left stood a wooden dock, its planks sun bleached but sturdy, and its pilings coated in algae but still standing. As she stepped onto the dock the boards creaked, but held fast. Stepping gracefully as to not make too much noise, she made her way to the end of the dock.

She dipped her hand in, the freshly melted frost giving the calm water a bit of a bite. Why am I so nervous, she thought to herself. I’ve done this dozens of times. Taking a deep breath, she called out, “Hey. It’s me. Can I come in?”

A lone bubble rose to the surface, letting out a loud “glorp” sound as it burst against the still air. Chloe smiled, leaned forward, and fell in.

While the water had sufficiently chilled her hand, the sensation was intensified a hundred fold over her entire body. It felt like she was entering the home of a snow spirit, or diving into the maw of an alpine dragon. She floated suspended in the frigid water for a few seconds, briefly wondering if the bubble had been a coincidence and she wasn’t coming.

But in a rush of water and fins Chloe’s fears evaporated, and she was hurled to the surface of the lake. Her legs were straddling the thick, slippery body of a lacus, or lake serpent. Lake serpent wasn’t a very accurate name, as while the creature had the long rope-like body structure found in snakes, it had smooth skin closer to that of a dolphin than the scales of a snake. Its long, horse-like face gazed down at her with enormous watery brown eyes, and two tendrils which sprouted from the area just behind its nostrils tasted the air around Chloe. The lake serpent was a deep greenish-brown color, with hints of grey and blue sprinkled in, especially on its head and the tip of its tail. Six leathery fins grew at even increments along the lacus’ body, making it look almost as if three different whales had been fused together to create it. After wiping away the water on her face, Chloe looked up at the enormous creature and screamed.

��Ronia! It’s so good to see you, it’s been too long!”

The lacus responded by nuzzling her with its large head, almost throwing her off with the force of the gesture.

Chloe laughed, and said, “Easy girl, easy. I know, I’m happy to see you too.”

Ronia pulled her head away, and gave Chloe a playful poke with one of her slender tendrils.

“Oh so that’s how you want to play it, huh? Well take that!” With this cry, Chloe reached down and threw a handful of water at the lake serpent.

Barely fazed by this attack, Ronia slapped one of her six fins against the grey surface of the lake, sending a deluge of water flying in Chloe’s direction. She had already been incredibly wet from the rain and her dive into the lake, but this splash really added insult to injury. After she recovered from her sputtering, the lacus gestured towards its neck.

“You really think I’m going to play with you after you did that? Really?”

Ronia gave Chloe a long, sad look with her giant brown eyes.

“Okay fine, but I’m not going to be happy about it.” Chloe locked her arms around the creature’s neck. It was the only place on its body skinny enough for her to fit her arms around, aside from the tip of its tail.

As soon as her hands locked together, Ronia was off. Fast as lightning, she leapt beneath the lake’s surface, dragging Chloe with her. The lake serpent’s six fins and large paddle-shaped tail worked in unison to propel the duo through the water at an incredible speed. After doing a lap around the bottom of the lake in a matter of seconds, Ronia raced towards the surface and leapt into the air, a jump high enough for her entire body to leave the water and for Chloe to make a water-logged scream before being plunged beneath the surface once again. This went on for quite a few minutes, with Ronia whipping through the depths of the lake while Chloe clung on for dear life and was swept through patches of lakeweed and clouds of mud, only for Ronia to jump out of the water long enough for Chloe to catch a ragged breath, and then the cycle would begin again.

Eventually Ronia grew tired, and she slowed her pace, coming to a stop in front of the wooden dock. A shaken, drenched Chloe dragged herself onto the dock, and lay there gasping for breath.

“Wow, you never get used to that,” she said, laughing and coughing up water at the same time. Chloe had been riding Ronia since her arms had been long enough to reach around the creature’s neck, but the heart pounding, water inhaling ride never got old.

Ronia paddled over slowly, arching her neck to look down on Chloe. She wiped a wet tendril across the girl’s face in concern.

Chloe giggled. “I’m alright girl, don’t worry. That ride was incredible, I just need some time to recover. You really pulled out all the stops for our last run.”

At the mention of last run, Ronia’s eyes grew big, and she drew back her head.

Seeing this, Chloe sighed. “Oh. You thought I was back.”

Ronia let out a noise that sounded like a bubble popping mixed with a horse’s whinny.

Chloe bit her lip. “No, I’m not back. I just came for a really quick visit to tell everyone about the new girl. I didn’t even have time to tidy up the house. Gosh, I hope it’s not too dusty in there. Anyways, I came to say goodbye. I’ll try to come back sometimes, but it’s a really long drive and I don’t have much vacation time and I have Tess and we don’t even own the property anymore and I have to take care of grandma and grandpa and …” She sniffed. “I’m going to miss you so much. I already did, when I was away.”

Ronia whinnied again, and swung her head around so it was resting on Chloe’s stomach.

“Promise me that you’ll be good to the new girl, okay? She’s going to have a really hard job, and I don’t think anybody up there,” she gestured to the forest with the arm that wasn’t pinned down by Ronia’s massive head, “is going to help much. Promise?”

Chloe held up her hand, with pinky extended. Ronia carefully wrapped a tendril around the finger, and they shook. Chloe beamed, then sighed.

“I have a train to catch. I’m sorry.” Ronia lifted her head, and Chloe stood up. “Come here.” She hugged the lake serpent’s great big head and sniffled. “I love you so much. Stay safe. Stay smart.” She began walking back along the dock, and toward the trail. Looking backward, she saw that Ronia was still watching. “And remember to help Maya!” she called over her shoulder, before walking into the forest once again, pretending that the wetness in her cheeks was from the rain.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There have been strange stories that I have heard from time to time during my travels, and one of the bizarre ones is the mention of "living rocks." People speak of stones and boulders that move on their own, without the hand of man or beast. Entire landscapes will change overnight, and rock formations will seemingly disappear without a trace. Some say it is the act of ghosts and spirits, those who died on mountains or in canyons. Others suggest a godly force, though this omnipotent being's motive is quite unknown. Regardless of what they believe, they shall speak wonders about these supposedly "living rocks" and will puzzle over them as if they were a great mystery. Whenever I hear this, I immediately bring up the fact that there are at least a dozen species of animals that look like rocks, and another dozen or so that wear rocks like armor. That is not even mentioning golems, who are quite literally piles of stone that can walk on their own. For changing landscapes and vanishing boulders, I would direct my suspicions towards trolls. A hungry troll in search of tasty minerals can easily knock things around or just pick up a slab of rock and wander off into the night. It's just one of these bizarre moments where it seems like nobody even thinks about things for more than a second, or bother to even learn about the world around them. When it comes to mountains and canyons, there are numerous species that look to disguise themselves with the scenery, and that often means looking like a rock. It would make much more sense that a Hammerbird was nesting somewhere during the first viewing and then ran off in search of food before the second! Why must we immediately jump to the mystical and magical? It frustrates me, but that is not what I am going to be ranting about in this entry. Instead, this tantrum of mine is supposed to lead to one of the major culprits of these tales: Stone Chimneys. Funny enough, these creatures are probably going to be the closest anyone gets to a "living rock" (save for golems, but those are artificially made), as their bodies are made of collected stone chunks and are capable of slithering across the landscape. How is this possible? Why, it is because of the Slime that dwells within the core of this structure! Like any "subspecies" that involves Slimes, Stone Chimneys are not actually a unique species. Rather they are just Slimes that have taken on a certain lifestyle. If you were to peel off all the stone pieces, you would just get a plain old Slime. These variations arise mainly in rocky areas, like mountains, canyons and cliffs. They can be found in hot and cold environments, though they tend to avoid places that experience freezing temperatures at a frequent rate. The creation of a Stone Chimney begins with a Slime collecting pieces of rock in their pseudobody and using it to build a makeshift shell. Their gooey parts will help stick the chunks together and hold them in place, eventually creating a solid piece of armor. As they collect and build, their pseudobodies will be buried beneath the stony exterior. The only place you will notice their slime is near the bottom, as they create a "foot" that they use to slither and crawl on. Near this base is where tendrils can emerge, working as simple arms to grab new rock pieces or fleeing prey. The term "Stone Chimney" comes from the shape these variations often take. For whatever reason, they seem to always go for a tower-like formation, building upward into a single stony column. Other shapes have been seen, but they are quite rare. Perhaps they do this to look big and intimidating? Or maybe tower height is important when it comes to mate selection? No one is sure at the moment. I did try asking a few of them, but many don't bother with chit-chat and simple talk. The best answer I got from a non-Stone Chimney Slime was "well, it looks pretty cool." While I do agree with them, I find that answer a bit lacking. After a Stone Chimney has built up their armored tower, they shall slither across the land in the ceaseless pursuit of food. "Pursuit" may be the wrong word, as Stone Chimney's move quite slow. They are kind of like giant, rocky snails, as they seem to always be crawling at a constant, but sluggish, pace. This slow speed does not hinder them in any way, though, as Stone Chimney's often feed on immobile food sources. The main staples of their diet are lichens and moss, common things that grow on the boulders and rock that litter the landscape. As they slither along, they shall steer themselves so that their paths go over large patches of these growths. When their foot comes in contact with these foodstuffs, their slime will rip them up and scour the surface clean. They are then drawn up into the tower where they are ground up and digested. The nutrients are transferred to the heart and the Slime enjoys a nice meal! During their travels, Stone Chimneys will happily accept other sources of food, like carrion or live prey. While the mention of carnivory may cause one to worry about the safety of their own skin, you need not fret. Stone Chimneys mainly eat small critters that hide in burrows or under rocks. When they crawl over a hole in the ground, a bit of slime from the pseudobody will slither down to investigate. If there is a meaty morsel hiding within, it shall nab it and pull it up to the surface. If a marmot or skink tries to flee an approaching Stone Chimney, it shall launch out its tendrils in hopes of grabbing them in a sticky mitt. They do not seek large prey during their hunts, as they prefer the kind that are already dead. That, however, does not mean they won't eat something that died when they tried to defend themselves.

Though slow and lazy looking, Stone Chimneys should be treated with care. Like any animal, they do not like to feel threatened and they are quite wary about predators. Their layers of rock are already a sign of their caution, as they hide their vulnerable hearts deep within this armor. When a threat is detected, the Slime will retract its foot and seal itself within the tower structure. Every crevice will be locked shut so no predators or parasites may reach their slimy parts. If the attacker is large, the Stone Chimney may chose to fight back. If one gives their chimney a close look, you may notice various openings that dot its exterior. These mouth-like holes can be opened and sealed at will, and many believe they are used as sensory organs. When under attack, though, these openings can be used as a defense. By building pressure up within their pseudobody, Stone Chimneys can launch chunks of rock from these holes with devastating force. These goo wrapped missiles can hit like they were fired from a slingshot and can easily break bone. If fired at one's head, it can knock you out cold or give you one heck of a headache! This method of defense is often aimed towards larger attackers, and is commonly used against trolls. These giant geophages tend to be curious when they notice their food moving, so they come in for a closer look. Not wanting their armor to be ripped off and eaten, the Stone Chimney will spit at them to drive them away. Though dangerous to us folk, such attacks are mere annoyances to the burly trolls. In fact, trolls are often spooked by this display and will scamper off with little more than a faint bruise. What also helps with scaring off trolls is the gooey remains that are left behind after the spitting. When the troll regains its composure, it may grow curious about the rock the...rock spat at them. Their first thought will be to taste it and it will give them a mouthful of bitter slime. The foul taste will further deter the troll from trying to eat the Stone Chimney, as it will find it to be quite gross. Due to their slow lifestyle and simple diet, Stone Chimneys are often seen as part of the landscape rather than a separate creature. People note them like you would a thorny bush or poisonous flower: an interesting sight, but one you should keep a safe distance from. That, however, has not stopped people from trying to make use of them! Apparently, there are tales of certain folk who tried to use Stone Chimney's as treasure chests. A thickly armored creature that spat rocks at foes and didn't understand the concept of money, the perfect guard (that's what they were thinking, not me. I am quite aware how dumb this idea is)! So these people would take their sacks of gold, cover it in moss pieces and plant them in the path of a crawling chimney. The treasure would be sucked up and stored inside, as the Slime would first try to eat it and then would keep it as a neat trinket. The person would then mark the chimney in some way so they could tell which one had their gold. At first this seemed like a great idea, as the Stone Chimney attacked those who tried to steal the treasure and kept it safe beneath its rocky armor. Unfortunately, as time went on, people began to realize the problem with this method. The main one was retrieving said treasure, as the Stone Chimney didn't care about who rightfully owned the gold. Any who approached got a rock to the face. In other cases, the Stone Chimney would shed or replace the piece that held the identifying mark, causing the owner to lose track of which Slime had their treasure. Lastly, and a bit more amusing, was the random chance that the Slime would use the sack of gold as a projectile when it came to self-defense. Thieves, owners or even the occasional troll could possibly get the horde of treasure spat at their face at lightening speeds! Talk about a speedy return! You better hope your money isn't launched at a troll, as then you have to try to get that sticky gob off the hide of a frightened giant! That would be a hoot to see! Outside of that poor idea, Stone Chimney's have also been the star of some interesting stories. One was the tale of a great ruler who wished to have a "walking castle." He wanted a fortress that could march across his kingdom, allowing him to survey his land and befuddle attackers. He turned to the Stone Chimneys to achieve this dream, as they were already living towers. Legends say he gather hundreds of them together and built special shells for them to wear. When combined, they would make a castle that could move on its own, or that was at least the theory. Turns out that Stone Chimneys aren't social creatures, and they don't like being packed close to one another. One can't have a mighty fortress when every piece of it is trying to go in a different direction. Depending on who you ask, the story as a different ending. In one variation, the ruler was humiliated by this attempt and fled to the unknown to hide his shame. Others say he scaled down the project and tried to build a single massive tower. These stories claim that he finished this tower and walked inside so he could ride his creation. Unfortunately he failed to realize that when you cause dozens of Slimes to link up with one another, they grow into one massive amalgamation. At that size, their stomachs tend to seek larger prey than marmots and lizards. They say the tower still roams the land to this day, devouring any who seek shelter within it. On the note of towers and building, certain cultures believe that ancient Stone Chimneys taught humanity how to build the impressive castles and walls they have today. It was through their knowledge that humanity learned the ways of architecture and engineering. While I do admit that humans build some amazing structures, I chalk that up to their ingenuity and intelligence. I am not saying Slimes are dumb, but I don't think they taught humans how to build such things. I mean honestly, why would humans need some ancient, wizened species to teach them how to stack rocks? Chlora Myron Dryad Natural Historian ----------------------------------------------------- More Slime variations! What fun!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The trail starts out wide. A road really. Big enough for both of us to walk side by side. —– The night before, Alexis and I camp at Deep Creek, packed in among families with their mountain bikes and barbecue grills and behemoth tents and their hammocks stacked three-high celebrating Labor Day. We haul out our packs and shift gear around on the picnic table in the dark: sleeping pads and bags, camp stove and pots, emergency first aid kits, camel baks, rope, binoculars. Noted chronicler of Appalachian customs, Horace Kephart, says that “to equip a pedestrian with shelter, bedding, utensils, food, and other necessities, in a pack so light and small that he can carry it without overstrain, is really a fine art.” As connoisseurs of fine art and as people unaccustomed to camping in bear country, Alexis and I sit there looking at the bear canister wondering how to fit a week’s food supply into its small, plastic body. Canister is a deceiving term; it’s more a barrel-shaped lunchbox, smaller than those igloo contraptions your dad took to work throughout your childhood. But by the evening’s end, after all the arrangements, our packs seem lighter and emptier than they should, maybe because we’re not hiking in the desert and we don’t have to carry our water supply. We sleep, hoping that we are pedestrians soundly equipped. After morning coffee, we drive up from Bryson City with fog and mist blanketing the Great Smoky Mountains and shrouding the beginning of the hike in mystery, like a gift waiting to be opened -Alexis and I giddy children. —– The trail starts out wide. A road along a stream. We walk side by side. There is a newness, an excitement. It’s been months since I’ve seen her. But there is also a simple familiarity. We descend a short ways before starting a gradual two day climb towards Clingman’s Dome, the highest point in Tennessee, followed by another three days alongside Forney Creek. Alongside us Noland Creek drops pleasantly over boulders covered with moss and lichen, a background noise that a Texas boy like myself equates more to a waterfall than a creek, as most of the creeks I knew growing up were seasonal at best. It’s late summer in the Smokies and Noland roars softly, like a highway in the distance. We reacquaint ourselves to the rhythm of conversation, to a cadence particular to those who share intimacy. We fall into step. We adjust our packs at the shoulders, on the hips, at the chest, and try to ease out the kinks in our knees, on the lower back, near the nape of the neck. Some conversations are like a collision of atoms. I think that’s what drew me to Alexis in the first place, the way conversation would bounce between topics and stories and big ideas, whirling and spinning closer and closer to answers or revelations, the way talking with her would make my skin feel alive. It’s like that again. And the trail is wide. A road really. We walk side by side and point out the fungi here, a red flower over there, the way the light hits the water through a gap in the trees, the way the rocks make the stream look like blown glass. We hurl atoms step by step. —– Horace Kephart has sad, deep eyes, like a bloodhound, and (at least in most of the pictures that remain of him) a thick mustache. He is thin and wiry, the embodiment of an outdoorsman at the turn of the 19th century, replete with the independent spirit that only a checkered bandana, a short brimmed mountain hat, and a wooden pipe can instill. I first ran into Kephart when reading John Graves’ Goodbye to a River, a wonderfully meandering account of a canoe trip down the Brazos and one of the finest pieces of nature writing that Texas can claim. Graves simply calls him “Ol Kep”. Kephart, a man of dual lives, is probably best remembered for his writings about camping and for advocacy efforts to create what is now known as Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Camping and Woodcraft (1906) is still considered by many as the encyclopedia on outdoor excursions; if you’ve ever wondered about how well certain woods burn, Ol Kep provides a hierarchy for the burn-ability of soft-woods and hard-woods in relation to dryness; if you’ve ever pondered the difference between types of tent canvas, he’ll let you know when to use duck, sea island, or egyptian cotton - he’ll also let you know their respective weights; if you’ve ever debated how to cook possum, he’s got an opinion on that too. Buried within arcane and detailed observations of outdoor living, Kephart also embeds gems of wisdom, truths about the human condition which are still relevant today. —– Along Noland Creek the sun breaks through the trees in rays and makes the leaves glow electric and yellow among the green. We lay out on the rocks in the middle of the stream like lizards soaking it up. We hammock in the afternoon and gather firewood for the evening. Later we eat ramen, and later still we fall asleep to the sound of water rounding out the edges of stone, softening the corners and turning millions of tiny, round rocks into even smaller grains of sand, carrying them to the oceans and blowing them into the deserts across the world. —– Prior to becoming an expert on wilderness places and peoples, Ol Kep was mostly a bookworm. After being the librarian at Cornell, Kephart moved to Italy to purchase and catalog books for a wealthy collector. Somewhere along the way he met and fell in love with a woman from New York and exchanged letters with her. Eventually he moved back to the states, married Laura Mack, had six children with her, became the head librarian at both Yale and in Saint Louis, made advances in classification and library organization, published articles in a myriad of magazines, and had a nervous breakdown. It was the nervous breakdown that led him to western North Carolina, “looking for a big primitive forest where [he] could build up strength anew and indulge [his] lifelong fondness for hunting, fishing and exploring new ground.” Sometimes escape comes at a price, though. He’d never see his wife or children again. But he would know the woods. And he’d know the bottom of a moonshine bottle, which may be what drove him to the woods anyways; it’s hard to predict which way the wind will blow a man, or what path he’ll walk down to find a bit of solace. —– Day two is the longest and hardest of our hike. After climbing to the lookout tower at Clingman’s dome to peer into a fog that covers the 360 view, we start the three and a half miles down to our campsite. The trail grows narrower and rockier as we descend, rock-scree rolling beneath our feet. Darkness falls fast, and clouds darken. We pull out our tarps as the rain falls, at first a gentle pattering, soon a thunderous downpour. We give up on dry shoes and yell out plans for setting up camp in the rain. At our campsite, plans become obsolete. Dinner is abandoned. We try to keep things dry as best as possible, then settle into our tent and wait till morning. We have fifteen hours to go. Grey in the tent slowly becomes black, like a world where color has been drained by an unseen hand turning down a dial, like a plug being pulled in a tub of murky water. —– When Alexis and I met, both of us were going through divorces. Conversation erupted. We talked about relationships and what happened with them when they fell apart. We talked about what it was like to see the person you married and feel like they were a stranger. About how suddenly you feel adrift in something that used to seem so good. She hopped on the back of my motorcycle and we’d go swim or get BBQ. There were things I could share that I couldn’t with anyone else, things that people who aren’t looking at the inside of a crumbling marriage can’t possibly understand and don’t usually want to talk about anyways. It’d be like trying to hang out with a bunch of Red Sox fans and strike up conversations about the Yankee’s bullpen - they’d have opinions and know a lot about baseball, but they’re primarily rooting for the other team. Nobody wants to see a marriage fail, so when it does, it’s hard to find people who want to hear you belabor the finer points of love’s dissolution. Not that my friends aren’t wonderful, they truly are. But I’d already been through several separations with Sarah, already had some of those conversations. But with Alexis, it was more than that. It was intimacy. Not a physical one, nor like the head-over-heels love of the movies. It was the discovery of a shared experience. It was finding someone who was walking through the same thing as you, and who could help you see that it would be okay. It wasn’t always pretty. She was there for long walks with me when the anxiety set in, when I felt my heart rising in my chest, trying to strangle me from within. I was there for her when she couldn’t find the strength to eat, when food seemed strange and alien. There were tears sometimes. There were questions that had no answers: How come you can love someone and then not love them? Is love even supposed to last forever? Who are we anyways and why are we here? Questions that I imagine are a far cry from most first dates, the usual lists of hobbies and favorite movies and where one went to school. But questions that helped me know it was alright. That helped me see the world was still a wonder waiting to be unfurled. That the world would always be a wonder, and that it mattered not if the questions had answers, but only that we asked them. It was also magic. We climbed a hill at my friend’s ranch, a 12 pack of Lone Star in tow, and watched the Persied rain down meteors. We danced in the honky-tonks because sleep wouldn’t come. We walked the streets and felt the lightning in our teeth, in our bones, and we looked for that same light in the hills and the the stars and the flowers and in the water as clear as glass. We jumped in and swam with reckless abandon because it felt good to be alive again. We woke again every day to the newness of it all. And soon, we found that the water was all around us, that wonder had encircled us like a secret cocoon, like a blanket on a winter’s day or a soft breeze in the heat of the afternoon. Link Wray says that living is better than dying, and food tastes better than gold. I still think he’s right. —– Most of Kephart’s life revolved around the corresponding rhythms of writing and booze, with the woods being his sanctuary for both. He worked tirelessly to push for the creation of a National Park in the Appalachians, writing about the people and places that make the region so uniquely fascinating. He became the foremost expert on how to live in those woods, and he championed the simple, yet profound ways that the locals had been living in that region long before he came along. Nestled among bits of information about how to hike or navigate or clean a fish, he fashioned philosophical gems to remind his readers that nowhere, absolutely nowhere, is a man as free as when he lives simply, with a few meager provisions and the willingness to go where the day beckons. Or that man can never truly be lost, as long as he doesn’t lay expectations to where he’ll end up, instead exploring with purpose the path ahead. Kephart lived out his days exploring the woods, finding out everything he could about the world around him. Cataloging because it’s what he did best. Organizing hierarchies and making lists and asking questions about the woods. A cut of the same cloth as Muir or Thoreau or Emerson, climbing trees in a thunderstorm to feel what a tree feels, trying to wrestle life itself out of the chaos of living. Kephart would eventually die in a car wreck on a moonshine run along with a fellow passenger. The driver lived, only to die on the same stretch of road ten years later. —– As Alexis and I walk along Noland Creek, along Forney Creek, in the same woods that Kephart loved, I wonder if the ruins beyond the creek are remnants of one of his makeshift cabins. If that giant elm near the campsite was brought down by a thunderstorm that made ol Kep shudder in his bones. I wonder how many times Kephart, too, marveled at the way the light hits the water and explodes into a thousand tiny suns. After the storm, the sun comes out again. Alexis and I stop in the places where the light lingers through the trees and let the warmth seep into our skin. We traverse several stream-crossings, the water running higher from last night’s rain. The water reaches our calves, our thighs, but we don’t topple. We find sticks that other travelers before us have used to ford the stream, and we reach for each other when the sticks don’t seem to be enough. We reach camp midday and make a clothesline with some paracord that was left at a previous campsite by an accidentally generous occupant. Our clothes and sleeping pads and bags and tents and pillows get strung up to dry. We do yoga and stretch out along the creek, dipping down into the cold water and coming up feeling alive and new, drying out like lizards on the rocks. The following day dawns the same but new: sun among the trees and a slow awakening. The trail ends much like it began, slow and wide. A road really. Big enough for both of us to walk side by side. There is a tunnel that leads back to the road where our car is parked. Inside the tunnel it is cool and dark, and the end of the tunnel frames the woods, making brilliant the greens and browns that we’ve been walking in for the past five days. It’s good to feel Alexis’s hand in mine again. It’s good to see a new road in front of me. It’s good to feel the change of seasons and feel the wind on my face. And it’s fitting that I have a Kephart quote running through my brain: “It is one of the blessings of wilderness life that it shows us how few things we need in order to be perfectly happy.” ------------------------------------------------------ *I’m no historian; this is a rough sketch of Kephart’s life at best. For more info, go here: https://www.wcu.edu/library/digitalcollections/kephart/aboutproject.htm

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

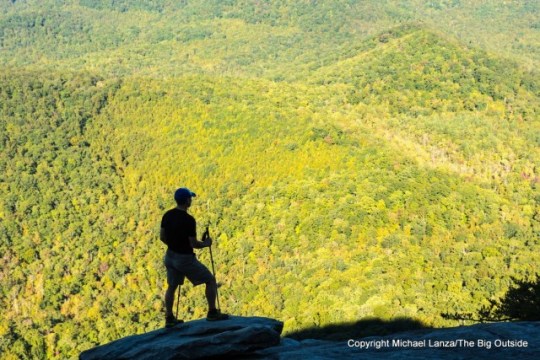

A hiker atop Looking Glass Rock, Pisgah National Forest, N.C.

By Michael Lanza

Warm rain drums lightly on the lush deciduous forest around me as I walk up a long-abandoned dirt road that has narrowed to a trail with the gradual encroachment of vegetation. The wind assaults the treetops, the outer edge of a hurricane hitting the Southeast coast right now; but here, far from the storm, it sounds like waves rhythmically lapping up onto a beach and retreating. It’s a gray, early evening in mid-October in the basement of a compact valley in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina—a valley that, due to its tight contours, sees precious few hours of direct sunlight at this time of year—and the daylight has filtered down to a soft, dim, tranquil quality.

A bit more than a half-mile up this quiet footpath, I reach my destination—and unconsciously catch my breath at what must be one of the most lovely cascades in a corner of North Carolina spilling over with waterfalls.

Roaring Fork Falls tumbles through a series of a dozen or more steps, each several feet high, before coming to rest briefly in a placid, knee-deep pool at its bottom. Beyond the pool, the stream continues downhill at an angle only somewhat less severe than the cascade above. In sunshine or warmer temperatures, I’d be tempted to wade in and sit in that pool. Now, I just stare at it, all but hypnotized.

Roaring Fork Falls, Pisgah National Forest, N.C.

I’m on the last, short hike of a day filled with beautiful waterfalls along the Blue Ridge Parkway, in the heart of one of America’s hiking and backpacking meccas: western North Carolina. I’ve come to spend a week chasing waterfalls, fall foliage color, and classic Southern Appalachian views while dayhiking in the mountains surrounding Asheville and backpacking in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Unlike soaring, jagged Western mountain ranges such as the Tetons, High Sierra, or North Cascades, the Appalachian Mountains are lower and mostly forested from bottom to top, their once-sharper angles of ancient epochs worn rounder and softer by erosion and time. (It happens to all of us.) From a high point like Looking Glass Rock, Black Balsam Knob, or any of numerous turnouts along the Blue Ridge Parkway, the mountains here resemble a roiling, green sea of trees.

The West has big vistas; the Appalachians have big vistas, too, but mostly small, more intimate scenery, the kind that you can literally reach out and touch. Here, you don’t just look at the scenery; you’re in it.

In a sense, I went to North Carolina to reconnect with my hiking roots. I became a hiker, backpacker, and climber in the northern reaches of the Appalachian chain—in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and on many other wooded, rocky, rugged, little mountain ranges that pepper the Northeast. I discovered as a young man that I really liked the arduous nature of hiking in the Northeast, the craggy, windblown summits, and the fullness and deep silence of the forest in all seasons.

In North Carolina’s mountains, I rediscovered the pleasure of walking a footpath with last year’s dead leaves crunching underfoot; passing shallow streams that speak in some unknown tongue as they chug over and around stones; standing on summits overlooking seemingly endless rows of green or blue ridges fading to far horizons.

But I also discovered the unique qualities of the Southern Appalachians. They are not as steep and rocky (or as hard on ankles and knees) as their northern cousins. They’re not as crowded as one might be led to believe. They harbor hundreds of waterfalls, possibly the richest stash of falling waters in the country.

And these woods are quite simply a very good place to help a person remember what’s most important in life.

Find your next adventure in your Inbox. Sign up for my FREE email newsletter now.

Looking Glass Rock

The dry, crisp air of early morning raises goosebumps on my bare legs and arms as I start chuffing uphill in the woods of the Pisgah National Forest, a short drive out of the pleasant, small town of Brevard, where I’m spending a couple of nights while exploring the area’s trails. One of western North Carolina’s most recognizable natural landmarks, Looking Glass Rock (lead photo at top of story), leads my list of hikes today, which explains why I’m on the Looking Glass Rock Trail shortly after 7 a.m.

Brevard happens to be the seat of Transylvania County, a place relevant to hikers because the county receives over 90 inches of rain annually—making it the wettest county in North Carolina—and has over 250 waterfalls. I’m visiting several of them on dayhikes this week along the BRP, in the Pisgah, and in Gorges State Park.

youtube

The Big Outside thanks musician Greg Bishop for the use of his music in the above video. Find more at https://store.cdbaby.com/artist/gregbishop and on iTunes.

The trail rises at a gentle angle at first; but as I climb higher, it grows steeper. In this quiet forest, with little variation in the scenery as I walk uphill, it’s easy to get lost in thoughts; and in a world where we’re almost constantly receiving texts and checking email, getting lost in your thoughts has become a rare joy.

After a few miles of steady uphill climbing, I step out of the forest onto a sloping, sprawling granite slab at the top of Looking Glass Rock—atop the cliffs that millions of tourists photograph from turnouts along the Blue Ridge Parkway every year. The morning sun hasn’t yet reached these slabs, but it throws a warm spotlight on gentle waves of hills rolling out a carpet of dappled green for miles in all directions before me.

If every person could start each day this way, I gotta think the world would be a more peaceful place.

Hi, I’m Michael Lanza, creator of The Big Outside, which has made several top outdoors blog lists. Click here to sign up for my FREE email newsletter. Subscribe now to get full access to all of my blog’s stories. Click here to learn how I can help you plan your next trip. Please follow my adventures on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Youtube.

Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway isn’t a highway you take when you want to get somewhere quickly; it exists for just the opposite objective: to get nowhere slowly. A narrow, two-way road snaking along the Blue Ridge from Shenandoah National Park in Virginia to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in western North Carolina, this 469-mile-long corridor through Eastern deciduous forest is, in many respects, America’s country road.

Begun in 1935 and finished more than half a century later with the completion of an engineering marvel, the Linn Cove Viaduct—an S-shaped bridge that hugs the side of North Carolina’s iconic Grandfather Mountain—it ranges in elevation from 600 feet to about 6,000 feet above sea level. From numerous places along it, one overlooks deep valleys in more shades of green than we have names for, steep-walled mountainsides draped in dense forest, and one overlapping mountain ridge after another.

The BRP also spans a wide range of habitats and supports more plant species—over 4,000—than any other park in the country. If you’re into fungi and look really, really hard, you’ll find 2,000 kinds of them, as well as 500 species of mosses and lichens. There are more varieties of salamander than anywhere else in the world. Wet, warm, and fertile, the Southern Appalachians are like a big orgy of photosynthesis that almost shocks the optic nerves, lasting for several months a year. Most of us rarely see such a conspicuous eruption of greenery.

With more than 100 trailheads and over 300 miles of trails scattered along its length, the BRP forms the spine of one gem of a trail system. (See my story “The 12 Best Dayhikes Along North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Parkway.”) That’s why, with a week to play on the trails of western North Carolina, I essentially made the Blue Ridge Parkway my base of operations.

Want to read any story linked here? Get full access to ALL stories at The Big Outside, plus a FREE e-guide. Subscribe now!

Moore Cove in the Pisgah National Forest, N.C.

Moore Cove

Millions of people live within driving distance of the parks and forests of the Appalachian Mountains. With over 15 million visits annually, the Blue Ridge Parkway ranks number one among all National Park Service sites for visitors, while Great Smoky Mountains National Park occupies the third spot on the list, with nearly 11 million visits a year. Not surprisingly, escaping the throngs in much of the Appalachian Mountains presents a formidable challenge—especially during fall foliage season.

But sometimes you just get lucky.