#like I had a friend tell me recently. after I successfully identified a car: ‘I could never see you as a car guy. You hate manual labor.’

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

^Slightly confused by this but decided to add it a n y w a y s

still so fucking weird to go from real life, where a cis man being flamboyant/effeminate/camp is judged like 70+% by how he speaks and carries himself, to online queer communities, which often seem to have no concept of male gender non-conformity that doesn’t involve wearing a skirt

#This is what I was talking about!#I mentioned to a moot the other day#that before transitioning— when I was a gnc ‘girl’ in men’s clothing#people perceived me as masculine#I remember my own mother seeing me one morning in my outfit for the day#and telling me I looked ‘butch’ and that no guy would ever like me or want to date me#because they’d assume I’m a lesbian#I was perceived as masculine because my clothes and attitude transgressed the feminine ideal#but after transitioning#people perceive me in the opposite direction#my style hasn’t changed. neither has my attitude#but my demeanor and attitude aren’t ’masculine enough’#to the point that it affects people’s perceptions of me#like I had a friend tell me recently. after I successfully identified a car: ‘I could never see you as a car guy. You hate manual labor.’#and I blinked. I hate going to public gyms. Because bathrooms. And people. I also hate running because my knees#but I used to dig holes for my father#(literally. my summers consisted of working in a gravel lot. no shade. digging holes for my dad)#and I also spent those summers working on my grandmother’s farm helping my grandpa out#a childhood of manual labor is why I’m shaped like a square today#and I volunteered to help out. I wanted to#even the slightest transgression against the masculine ideal—forget not being straight or cis—invalidates your manhood & masculinity#it’s fucking wild#<prev tags. Holy shit

102K notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Scams The Scammers? Meet The Scambaiters

Police struggle to catch online fraudsters, often operating from overseas, but now a new breed of amateurs are taking matters into their own hands

— Amelia Tait | Sunday, 03 October 2021 | Guardian USA

‘My computer’s giving me the worst vibes,’ began Rosie in Kim Kardashian’s voice. Illustration: Pete Reynolds/The Observer

Three to four days a week, for one or two hours at a time, Rosie Okumura, 35, telephones thieves and messes with their minds. For the past two years, the LA-based voice actor has run a sort of reverse call centre, deliberately ringing the people most of us hang up on – scammers who pose as tax agencies or tech-support companies or inform you that you’ve recently been in a car accident you somehow don’t recall. When Okumura gets a scammer on the line, she will pretend to be an old lady, or a six-year-old girl, or do an uncanny impression of Apple’s virtual assistant Siri. Once, she successfully fooled a fake customer service representative into believing that she was Britney Spears. “I waste their time,” she explains, “and now they’re not stealing from someone’s grandma.”

Okumura is a “scambaiter” – a type of vigilante who disrupts, exposes or even scams the world’s scammers. While scambaiting has a troubled 20-year online history, with early forum users employing extreme, often racist, humiliation tactics, a new breed of scambaiters are taking over TikTok and YouTube. Okumura has more than 1.5 million followers across both video platforms, where she likes to keep things “funny and light”.

“I waste their time and now they’re not stealing from someone’s grandma.” — Rosie Okumura

In April, the then junior health minister Lord Bethell tweeted about a “massive sudden increase” in spam calls, while a month earlier the consumer group Which? found that phone and text fraud was up 83% during the pandemic. In May, Ofcom warned that scammers are increasingly able to “spoof” legitimate telephone numbers, meaning they can make it look as though they really are calling from your bank. In this environment, scambaiters seem like superheroes – but is the story that simple? What motivates people like Okumura? How helpful is their vigilantism? And has a scambaiter ever made a scammer have a change of heart?

Batman became Batman to avenge the death of his parents; Okumura became a scambaiter after her mum was scammed out of $500. In her 60s and living alone, her mother saw a strange pop-up on her computer one day in 2019. It was emblazoned with the Windows logo and said she had a virus; there was also a number to call to get the virus removed. “And so she called and they told her, ‘You’ve got this virus, why don’t we connect to your computer and have a look.” Okumura’s mother granted the scammer remote access to her computer, meaning they could see all of her files. She paid them $500 to “remove the virus” and they also stole personal details, including her social security number.

Thankfully, the bank was able to stop the money leaving her mother’s account, but Okumura wanted more than just a refund. She asked her mum to give her the number she’d called and called it herself, spending an hour and 45 minutes wasting the scammer’s time. “My computer’s giving me the worst vibes,” she began in Kim Kardashian’s voice. “Are you in front of your computer right now?” asked the scammer. “Yeah, well it’s in front of me, is that… that’s like the same thing?” Okumura put the video on YouTube and since then has made over 200 more videos, through which she earns regular advertising revenue (she also takes sponsorships directly from companies).

“A lot of it is entertainment – it’s funny, it’s fun to do, it makes people happy,” she says when asked why she scambaits. “But I also get a few emails a day saying, ‘Oh, thank you so much, if it weren’t for that video, I would’ve lost $1,500.’” Okumura isn’t naive – she knows she can’t stop people scamming, but she hopes to stop people falling for scams. “I think just educating people and preventing it from happening in the first place is easier than trying to get all the scammers put in jail.”

She has a point – in October 2020, the UK’s national fraud hotline, run by City of London Police-affiliated Action Fraud, was labelled “not fit for purpose” after a report by Birmingham City University. An earlier undercover investigation by the Times found that as few as one in 50 fraud reports leads to a suspect being caught, with Action Fraud frequently abandoning cases. Throughout the pandemic, there has been a proliferation of text-based scams asking people to pay delivery fees for nonexistent parcels – one victim lost £80,000 after filling in their details to pay for the “delivery”. (To report a spam text, forward it to 7726.)

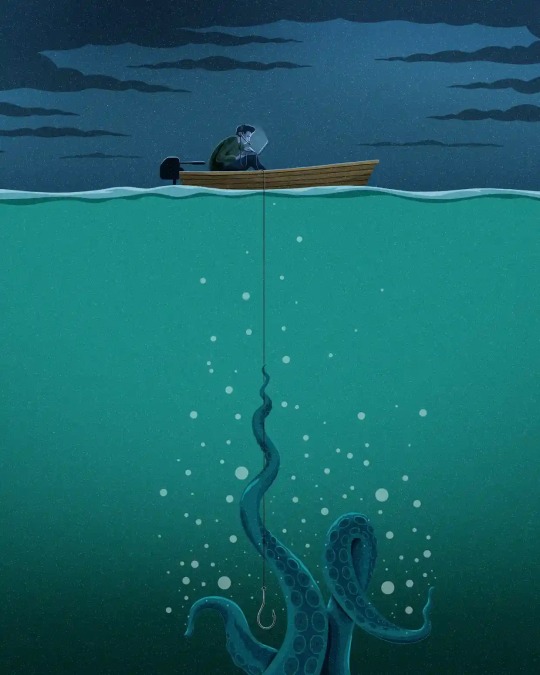

Hook, line and sinker: the scambaiters. Illustration: Pete Reynolds

Asked whether vigilante scambaiters help or hinder the fight against fraud, an Action Fraud spokesperson skirted the issue. “It is important people who are approached by fraudsters use the correct reporting channels to assist police and other law enforcement agencies with gathering vital intelligence,” they said via email. “Word of mouth can be very helpful in terms of protecting people from fraud, so we would always encourage you to tell your friends and family about any scams you know to be circulating.”

Indeed, some scambaiters do report scammers to the police as part of their operation. Jim Browning is the alias of a Northern Irish YouTuber with nearly 3.5 million subscribers who has been posting scambaiting videos for the past seven years. Browning regularly gets access to scammers’ computers and has even managed to hack into the CCTV footage of call centres in order to identify individuals. He then passes this information to the “relevant authorities” including the police, money-processing firms and internet service providers.

“I wouldn’t call myself a vigilante, but I do enough to say, ‘This is who is running the scam,’ and I pass it on to the right authorities.” He adds that there have only been two instances where he’s seen a scammer get arrested. Earlier this year, he worked with BBC’s Panorama to investigate an Indian call centre – as a result, the centre was raided by local police and the owner was taken into custody.

Browning says becoming a YouTuber was “accidental”. He originally started uploading his footage so he could send links to the authorities as evidence, but then viewers came flooding in. “Unfortunately, YouTube tends to attract a younger audience and the people I’d really love to see looking at videos would be older folks,” he says. As only 10% of Browning’s audience are over 60, he collaborates with the American Association of Retired People to raise awareness of scams in its official magazine. “I deliberately work with them so I can get the message a little bit further afield.”

Still, that doesn’t mean Browning isn’t an entertainer. In his most popular upload, with 40m views, he calmly calls scammers by their real names. “You’ve gone very quiet for some strange reason,” Browning says in the middle of a call, “Are you going to report this to Archit?” The spooked scammer hangs up. One comment on the video – with more than 1,800 likes – describes getting “literal chills”.

But while YouTube’s biggest and most boisterous stars earn millions, Browning regularly finds his videos demonetised by the platform – YouTube’s guidelines are broad, with one clause reading “content that may upset, disgust or shock viewers may not be suitable for advertising”. As such, Browning still also has a full-time job.

YouTube isn’t alone in expressing reservations about scambaiting. Jack Whittaker is a PhD candidate in criminology at the University of Surrey who recently wrote a paper on scambaiting. He explains that many scambaiters are looking for community, others are disgruntled at police inaction, while some are simply bored. He is troubled by the “humiliation tactics” employed by some scambaiters, as well as the underlying “eye for an eye” mentality.

“I’m someone who quite firmly believes that we should live in a system where there’s a rule of law,” Whittaker says. For scambaiting to have credibility, he believes baiters must move past unethical and illegal actions, such as hacking into a scammer’s computer and deleting all their files (one YouTube video entitled “Scammer Rages When I Delete His Files!” has more than 14m views). Whittaker is also troubled by racism in the community, as an overcrowded job market has led to a rise in scam call centres in India. Browning says he has to remove racist comments under his videos.

“I think scambaiters have all the right skills to do some real good in the world. However, they’re directionless,” Whittaker says. “I think there has to be some soul- searching in terms of how we can better utilise volunteers within the policing system as a whole.”

At least one former scambaiter agrees with Whittaker. Edward is an American software engineer who engaged in an infamous bait on the world’s largest scambaiting forum in the early 2000s. Together with some online friends, Edward managed to convince a scammer named Omar that he had been offered a lucrative job. Omar paid for a 600-mile flight to Lagos only to end up stranded.

“He was calling us because he had no money. He had no idea how to get back home. He was crying,” Edward explains. “And I mean, I don’t know if I believe him or not, but that was the one where I was like, ‘Ah, maybe I’m taking things a little too far.’” Edward stopped scambaiting after that – he’d taken it up when stationed in a remote location while in the military. He describes spending four or five hours a day scambaiting: it was a “part-time job” that gave him “a sense of community and friendship”.

“I mean, there’s a reason I asked to remain anonymous, right?” Edward says when asked about his actions now. “I’m kind of embarrassed for myself. There’s a moment where it’s like, ‘Oh, was I being the bad guy?’” Now, Edward doesn’t approve of vigilantism and says the onus is on tech platforms to root out scams.

Yet while the public continue to feel powerless in the face of increasingly sophisticated scams (this summer, Browning himself fell for an email scam which resulted in his YouTube channel being temporarily deleted), But scambaiting likely isn’t going anywhere. Cassandra Raposo, 23, from Ontario began scambaiting during the first lockdown in 2020. Since then, one of her TikTok videos has been viewed 1.5m times. She has told scammers her name is Nancy Drew, given them the address of a police station when asked for her personal details, and repeatedly played dumb to frustrate them.

“I believe the police and tech companies need to do more to prevent and stop these scams, but I understand it’s difficult,” says Raposo, who argues that the authorities and scambaiters should work together. She hopes her videos will encourage young people to talk to their grandparents about the tactics scammers employ and, like Browning, has received grateful emails from potential victims who’ve avoided scams thanks to her content. “My videos are making a small but important difference out there,” she says. “As long as they call me, I’ll keep answering.”

For Okumura, education and prevention remain key, but she’s also had a hand in helping a scammer change heart. “I’ve become friends with a student in school. He stopped scamming and explained why he got into it. The country he lives in doesn’t have a lot of jobs, that’s the norm out there.” The scammer told Okumura he was under the impression that, “Americans are all rich and stupid and selfish,” and that stealing from them ultimately didn’t impact their lives. (Browning is more sceptical – while remotely accessing scammers’ computers, he’s seen many of them browsing for the latest iPhone online.)

“At the end of the day, some people are just desperate,” Okumura says. “Some of them really are jerks and don’t care… and that’s why I keep things funny and light. The worst thing I’ve done is waste their time.”

0 notes

Text

Abortion by Telemedicine: A Growing Option as Access to Clinics Wanes

Ashley Dale was grateful she could end her pregnancy at home.As her 3-year-old daughter played nearby, she spoke by video from her living room in Hawaii with Dr. Bliss Kaneshiro, an obstetrician-gynecologist, who was a 200-mile plane ride away in Honolulu. The doctor explained that two medicines that would be mailed to Ms. Dale would halt her pregnancy and cause a miscarriage.“Does it sound like what you want to do in terms of terminating the pregnancy?” Dr. Kaneshiro asked gently. Ms. Dale, who said she would love to have another baby, had wrestled with the decision, but circumstances involving an estranged boyfriend had made the choice clear: “It does,” she replied.Now, the coronavirus pandemic is catapulting demand for telemedicine abortion to a new level, with much of the nation under strict stay-at-home advisories and as several states, including Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas, have sought to suspend access to surgical abortions during the crisis.The telemedicine program that Ms. Dale participated in has been allowed to operate as a research study for several years under a special arrangement with the Food and Drug Administration. It allows women seeking abortions to have video consultations with certified doctors and then receive abortion pills by mail to take on their own.Over the past year, the program, called TelAbortion, has expanded from serving five states to serving 13, adding two of those — Illinois and Maryland — as the coronavirus crisis exploded. Not including those new states, about twice as many women had abortions through the program in March and April as in January and February.To accommodate women during the pandemic, TelAbortion is “working to expand to new states as fast as possible,” said Dr. Elizabeth Raymond, senior medical associate at Gynuity Health Projects, which runs the program. It is also hearing from more women in neighboring states seeking to cross state lines so TelAbortion can serve them.As of April 22, TelAbortion had mailed a total of 841 packages containing abortion pills and confirmed 611 completed abortions, Dr. Raymond said. Another 216 participants were either still in the follow-up process or have not been in contact to confirm their results. The program’s growth is significant enough that Republican senators recently introduced a bill to ban telemedicine abortion.The F.D.A., which has allowed TelAbortion to continue operating during the Trump administration, declined to answer questions from The New York Times about the program.The F.D.A. rules, however, do not specify that providers must see patients in person, so some clinics have begun allowing women to come in for video consultations with certified doctors based elsewhere. TelAbortion goes further, offering telemedicine consultations to women at home (or anywhere), mailing them pills and following up after women take them.In interviews, seven women who terminated pregnancies through TelAbortion described the conflicting emotions and intricate logistics that can accompany a decision to have an abortion, and their reasons for choosing to do it through telemedicine.Ms. Dale, a single mother, was about to start a job at a storage center when she became pregnant last year. She would have had to fly to Honolulu, incurring expenses for travel and child care.“The alternative would be to wait for a doctor to come to my island in three weeks,” Ms. Dale, 35, told Dr. Kaneshiro during her consultation, which she allowed a Times reporter to observe. By then, she would be too pregnant for a medication abortion.But many TelAbortion patients live near clinics. Shiloh Kirby, 24, of Denver, who said she had become pregnant after being raped at a party, chose TelAbortion for convenience and privacy. She conducted her video consultation while sitting in her car in the parking lot of the hardware store where she worked.Dawn, 30, a divorced mother of two who asked to be identified only by her first name, was terrified that the debilitating postpartum depression she experienced after her children’s births would return if she continued her pregnancy. And she worried protesters at her local Planned Parenthood in Salem, Ore., might recognize her.“I just don’t want to deal with that ridicule,” she said.

Expanding across the country

Based on state laws governing telemedicine and abortion, Dr. Raymond estimated TelAbortion might be legal in slightly over half of the states, including some conservative ones. It now serves Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Oregon and Washington.The doctors (and nurses or midwives in some states) who do TelAbortion’s video consultations must be licensed in states where medication is mailed, but do not have to practice there. Likewise, patients do not have to live in the states that TelAbortion serves; they just have to be in one of them during the videoconference and provide an address there — that of a friend, relative, even a motel or post office — to which pills can be shipped.“We have had patients who cross state lines in order to receive TelAbortions,” Dr. Raymond said. More are expected to do so during the pandemic. This month, a woman from Texas drove 10 hours in snowy weather to New Mexico, where she stayed in a motel for her videoconference and to receive the pills.The organization that provides TelAbortion services in Georgia, carafem, has expanded recently to Maryland and Illinois, and it is running digital ads that are expected to reach women in some nearby states like Missouri and Ohio, which have more abortion restrictions, said Melissa Grant, carafem’s chief operations officer.In May, shortly after Georgia’s governor signed one of the country’s strictest abortion laws (which is now being challenged in court), Lee, 37, who lives near Atlanta, discovered she was seven weeks pregnant.Lee, who asked to be identified only by a shortened version of her first name, said the pregnancy had shocked her because she took birth control pills regularly. She decided to terminate the pregnancy because she had recently cut ties with her boyfriend after he was arrested on drug charges, she said.She kept her decision from her family members, who she said were strongly against abortion. And she feared protesters would castigate her if she visited an abortion clinic.“No one goes through life saying, ‘I’m going to grow up and get an abortion,’” Lee said. “So you’re already struggling with that and then to have someone tell you that you’re going to hell or that you’re killing babies, it’s horrible.”She found carafem, and videoconferenced in her office at lunchtime with a doctor in another state.During such consultations, doctors explain that most women do not experience discomfort from mifepristone, which blocks a hormone necessary for pregnancy to develop. Cramping and bleeding, resembling a heavy period, occur after the expulsion of fetal tissue caused by the second drug, misoprostol, which is taken up to 48 hours later. After several hours, bleeding dwindles but might continue for two weeks. In rare cases, women can develop fevers, infections or extensive bleeding requiring medical attention.Lee received a package marked only with her name and address; it contained the pills, tea bags, peppermints, maxipads, prescription ibuprofen and nausea medication.“Just everything you could need,” she said. “It was so comforting.”TelAbortion reports that of the 611 completed abortions documented through April 22, most were accomplished with only the pills and without complications. In 26 cases, aspiration was performed to finish the termination.Dr. Raymond said 46 women went to emergency rooms or urgent care centers with issues that appear just as likely to have occurred if the women had followed the common practice of visiting abortion clinics for consultations, taking the first medication there and the second at home. Two women went before receiving the pills and two before taking them, either because of morning sickness or because they thought they were miscarrying. Fifteen ended up needing no medical treatment. Some were given medicine for pain or nausea.Three were hospitalized, all successfully treated: two women had excessive bleeding, and another had a seizure after an aspiration, Dr. Raymond said.Eleven women decided not to have abortions and did not take the pills they were sent. Another woman continued her pregnancy after the medication failed, as did another after vomiting the mifepristone. Sixteen women have undergone two telabortions, Dr. Raymond said.Of the women The Times interviewed, only Dawn, who said she has anxiety, called the 24-hour TelAbortion line for emotional support.“It was after I took the pills,” Dawn said. “I felt like my body, my hormones essentially crashed. And because I suffer from mental health issues, just everything was just kind of out of whack and I started really panicking bad. I called the nurse and she just sat on the phone with me.”

Complex decisions

TelAbortion typically charges $200 to $375 for consultations and pills. Women must also pay for an ultrasound and lab tests, obtained from any provider. During the coronavirus pandemic, TelAbortion may waive its requirement for an ultrasound to gauge the gestational age of the pregnancy if women are unable to visit a doctor to obtain one, Dr. Raymond said. In some states, some or all of the costs are covered by private insurance or Medicaid. For women facing financial hardship, like Ms. Kirby in Denver, the program taps abortion grant networks.Some patients said the teleconsultations helped them navigate the complex feelings that abortion can evoke.Leigh, a 28-year-old construction inspector in Denver, who asked to be identified only by her middle name, said she considered herself “totally pro-life.”But, she said, she also has depression, which became so severe after she had a baby two years ago that she sometimes felt suicidal. Doctors, she said, “didn’t trust me alone with my baby.”Last March, after discovering she was pregnant and consulting her fiancé, she called Planned Parenthood. “I said, ‘I don’t want to be this person, but I need to abort this pregnancy,’” Leigh said.She chose the TelAbortion option. After taking the first medication, she attended a previously scheduled photo shoot for engagement pictures with her fiancé, then took the second medication that evening.Conducting her follow-up call from a field on a job site, Leigh told the doctor, Kristina Tocce, medical director of Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains, that she felt compelled to abort “no matter how much I hate myself.”When she sees a baby now, she says she still sometimes wonders, “‘Did I make the wrong choice?’”“I wanted to keep my baby, but I just couldn’t,” she said.During Ms. Dale’s videoconference in Hawaii, Dr. Kaneshiro spoke calmly.“It is pretty normal to pass some blood clots that maybe are even the size of a quarter,” she said.“I’m prepared because I actually had a miscarriage last year at four months along,” Ms. Dale replied.“This will not be that bad — I mean, at this stage of pregnancy, the actual embryo is smaller than the size of a grain of rice,” Dr. Kaneshiro said. “It’s very unlikely to see anything that’s recognizable as a pregnancy.”“OK, that’s good,” said Ms. Dale, then eight and a half weeks pregnant.“It doesn’t affect future pregnancies, so it doesn’t have any long-term effects,” Dr. Kaneshiro said.“OK, that was one of my questions, thank you,” Ms. Dale said.“Mommy, mommy!” called her daughter, Sophia, bouncing into the living room from a bedroom filled with Legos and a pop-up castle.“She’s beautiful,” Dr. Kaneshiro said.Ms. Dale’s consultation and lab tests were covered by Hawaii public assistance. The pills, which cost her $135, arrived by certified mail. She placed them on a table near two pregnancy ultrasound photos.“OK, this is happening,” Ms. Dale said she told herself. “I’m doing this.”Her reasons partly involved disagreements with her estranged boyfriend, the father of Sophia, now 4. Their strained relationship made Ms. Dale believe she would have to raise their second child alone.“I’ve got a beautiful daughter and I’d really love to have another one,” she said. “But it’s just not feasible for my sanity, and I feel like I’d basically be guaranteeing us to live in poverty.”On the back of an ultrasound picture, she wrote: “Never forget why you had to make the hard decision to let this baby go.” She swallowed the pill.She had Sophia stay at her mother’s house and took the other tablets, which she said felt like chalk in her mouth. To distract from seven hours of cramping and heavy bleeding, she watched back-to-back “Matrix” movies.“It’s not like it was easy,” she reflected later, “but at the same time it’s pretty clearly the right choice.” Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover http://www.nature-business.com/nature-a-year-after-hurricane-harvey-houstons-poorest-neighborhoods-are-slowest-to-recover/

Nature

HOUSTON — Hurricane Harvey ruined the little house on Lufkin Street. And ruined it remains, one year later.

Vertical wooden beams for walls. Hard concrete for floors. Lawn mowers where furniture used to be. Holes where the ceiling used to be. Light from a lamp on a stool, and a barricaded window to keep out thieves. Even the twig-and-string angel decoration on the front door — “Home is where you rest your wings” — was askew.

Monika Houston walked around her family’s home and said nothing for a long time. Tears streamed down her cheeks. She and her relatives have been unable, in the wake of the powerful storm that drenched Texas last summer, to completely restore both their house and their lives. Ms. Houston, 43, has been living alternately in a trailer on the front lawn, at her family’s other Harvey-damaged house down the block, with friends and elsewhere. Outside the trailer were barrels for campfires, set not to stay warm but to keep the mosquitoes away.

What help Ms. Houston’s family received from the government, nonprofit groups and volunteers was not enough, and she remains in a state of quasi-homelessness. She pointed to the dusty water-cooler jug by the open front door; inside were rolls of pennies, loose change and a crumpled $2 bill.

“That’s our savings,” she said as she picked up the jug and slammed it down. “We’ve never been in a position to save. We’ve been struggling, trying to hold onto what we have. This is horrible, a year later. I’m not happy. I’m broken. I’m sad. I’m confused. I’ve lost my way. I’m just as crooked as that angel on that door.”

Image

Monika Houston, 43, has been living in a trailer in front of her flooded and gutted home.

Houston and other Texas cities hit hard by Harvey a year ago have made significant progress recuperating from the worst rainstorm in United States history. The piles of debris — nearly 13 million cubic yards of it — are long gone, and many residents are back in their refurbished homes. Billions of dollars in federal aid and donations have helped Texans repair, rebuild and recover.

But this is not uniformly the case, and the exceptions trace a disturbing path of income and race across a state where those dividing lines are often easy to see.

A survey last month showed that 27 percent of Hispanic Texans whose homes were badly damaged reported that those homes remained unsafe to live in, compared to 20 percent of blacks and 11 percent of whites. There were similar disparities with income: 50 percent of lower-income respondents said they weren’t getting the help they needed, compared to 32 percent of those with higher incomes, according to the survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Episcopal Health Foundation.

In many low-income neighborhoods around Houston, it feels like Harvey struck not last year but last month. Some of Houston’s most vulnerable and impoverished residents remain in the early stages of their rebuilding effort and live in the shadows of the widespread perception that Texas has successfully rebounded from the historic flooding.

In the poorest communities, some residents are still living with relatives or friends because their homes remain under repair. Others are living in their flood-damaged or half-repaired homes, struggling in squalid and mold-infested conditions. Still others have moved into trailers and other structures on their property.

One 84-year-old veteran, Henry Heileman, lived until recently in a shipping container while his home was being worked on. The container, which had been transformed into a mini-apartment with a bathroom, bed and lattice-lined foundation, was roughly 42 feet long and 6 feet wide.

The recovery has been problematic for the African-American and Hispanic families who live in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods for several reasons. The scale of Harvey’s devastation and the depths of the social ills that existed in the Houston area before the storm played a role. So did a scattershot recovery that saw some people get the government aid and charity assistance they needed, when they needed it, while others had more difficulty or became entangled in disputes and complications with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“Everything always hits the poor harder than it does everybody else,” said John Sharp, the head of the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas, which is helping to coordinate the state response to Harvey and to assist local officials and nonprofit groups.

These residents have not struggled in isolation. They have been assisted in the past year by officials and volunteers, but their repairs and recovery stalled for different reasons. Some of them no longer seek out help and suffer privately, ashamed of their living conditions but unable to move forward with their lives. Their housing issues are one of many problems they are confronting post-Harvey. Some are disabled, ill, unemployed or caring for older relatives. Some said they or their relatives are taking medication or undergoing counseling to cope with post-Harvey stress.

“In New Orleans, you could see the remnants of Katrina by the markings of FEMA spray paint on people’s homes, and you could see those waterlines,” said Amanda K. Edwards, a Houston city councilwoman who has led an effort to identify and knock on the doors of low-income flood victims who have stopped answering phone calls from those trying to assist them. “Those types of visuals are not present here. So it is difficult for people to really appreciate how difficult of a time people are having.”

Image

Amanda Edwards, 36, a Houston city councilwoman, drives through neighborhoods that were badly hit during Hurricane Harvey.

Days after the one-year anniversary of Harvey’s Texas landfall on Aug. 25, Ms. Edwards drove to the home of a victim in the Houston Gardens neighborhood. She parked in the driveway of a flood-damaged home that, from the outside, appeared in good condition. Ms. Edwards was told that the African-American man inside lives in his home without electricity. As Ms. Edwards stood on the man’s doorstep, he called out to her with the door closed, telling her he did not want any visitors.

Nearby, Ms. Edwards was given a tour of Kaverna Moore’s gutted home. Ms. Moore, 67, lived in her home for months after Harvey and finally moved in with her son in March. Her repairs stalled after she was denied disaster assistance by FEMA.

She sorted through her papers and pulled out the FEMA denial letter. It was dated September 23, 2017, and stated that she was ineligible because “the damage to your essential personal property was not caused by the disaster.” The letter baffles her. She lost her furniture, her carpet, her shoes and her appliances when about 2 feet of floodwater inundated her home. A contractor’s estimate to repair the damage to the physical structure, including replacing the sheet rock and installing new doors, was $18,605. She appealed the FEMA denial but never heard back.

She said she has no idea when she will be back in her home. She was waiting for Habitat for Humanity to work on the house.

“I miss my house,” Ms. Moore said. “I miss it a whole lot. I come by every day. Check my mail. Sometimes I come and sit on the porch.”

Image

Kaverna Moore, 67, was living in her gutted and moldy house until March, when she had to have surgery and moved in with her son.

Image

Patricia Crawford waits, too.

Ms. Crawford’s house remains under repair while she undergoes cancer treatment. Ms. Crawford, 74, went to live with a friend after Harvey. She moved back into her house — the house she grew up in — in June, before it was ready, then moved out after a few days. Her house remains a work in progress, with unpainted walls and construction padding on the floors, the rooms strewn with power tools. Her bed is still tightly wrapped in plastic.

She received some money from FEMA but was denied other assistance. So she waits, living with another friend and counting on help from relatives and nonprofit groups like the Fifth Ward Community Redevelopment Corporation.

“It’s been hard,” Ms. Crawford said one afternoon as she sat on a sofa at her half-finished house. “Have you ever felt like you were just lost? Well, that’s the way I feel. I feel lost. My doctor told me that if I didn’t stop grieving, she was going to put me in the hospital. But I’m doing better.”

Image

Patricia Crawford, 74, visits her home in the Kashmere Gardens neighborhood of Houston.

No local, state or federal agency has been tracking how many people remain displaced after Harvey. It is unclear how many residents are struggling to complete repairs or have had their recovery stall. In the Kashmere Gardens section of northeast Houston — the low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhood along Interstate 610 where Ms. Houston and Ms. Crawford live — Keith Downey, a community leader, estimated that at least 1,500 Harvey victims in the area were not back in their homes.

In the Kaiser and Episcopal survey, based on phone interviews with more than 1,600 adults in 24 Harvey-damaged counties in June and July, three out of 10 residents said their lives were still “very” or “somewhat” disrupted from the storm.

The race and income disparities identified in the survey are likely a result of what existed before the storm, said Elena Marks, president and chief executive of the Episcopal Health Foundation and a former health policy director for the city of Houston. “If you went into the storm with relatively few resources, and then you lost resources, be it income or property or car, it’s going to be harder for you to replace it,” she said. “The farther behind you were before the storm, the less likely you are to bounce back after the storm.”

Local, state and federal officials expressed concern for low-income Harvey victims, but they were unable to explain why so many of them continue to struggle. City officials say there has been no shortage of resources and services for poor residents affected by the storm, including the 14 neighborhood restoration centers the city opened, mostly in low-income areas. FEMA said it has put $4.3 billion into the hands of affected Houstonians.

“There are thousands of families who live in low-income communities, who already were operating at the margins before Harvey, and the storm pushed them down even further,” the mayor of Houston, Sylvester Turner, said in an interview. “We want to reassure them that they have not been forgotten.”

Mr. Turner, who visited Kashmere Gardens and other neighborhoods to mark the anniversary of Harvey, described the problem as a federal and state issue, citing the $5 billion in federal Community Development Block Grant disaster-recovery funds that were approved for Texas, but that Houston has yet to receive.

“We know that the city is going to receive $1.14 billion dollars in C.D.B.G. funding for housing,” Mr. Turner said. “But you can’t disperse what you don’t have.”

Kurt H. Pickering, a spokesman for FEMA in Texas, said the agency had seen no evidence that low-income areas were receiving less support from the agency. He said that federal assistance was designed not to make a person whole after a disaster, but to help start the recovery process. “FEMA does everything possible to assist every family in every way,” within the bounds of its regulations, Mr. Pickering said.

In Kashmere Gardens, Ms. Houston ended the tour of her house on Lufkin Street after a few minutes.

“I can’t stay in here too long because I start coughing,” she said.

She spoke of the past 12 months as a series of disputes and broken promises. She said she felt abandoned by FEMA, contractors, reporters and celebrities who visited the neighborhood and failed to follow up on repairs. “We’re no more than 15 minutes from River Oaks,” she said, referring to one of the wealthiest areas of Houston. “It’s not just the government. Don’t nobody care.”

Ms. Houston, a former truck driver, walked to the middle of Lufkin and turned around to face the house. The yard with the trailer was cluttered, but the house appeared normal.

“When you stand here, you would never know what lies behind those walls,” she said. “Look at it. You don’t even know how broken it is. That’s the sad part.”

Image

A portrait of Patricia Crawford’s parents still hangs in her home, although she is unable to move back.

Michelle O’Donnell contributed reporting from Houston.

Manny Fernandez is the Houston bureau chief, covering Texas and Oklahoma. He joined The Times as a Metro reporter in 2005, covering the Bronx and housing. He previously worked for The Washington Post and The San Francisco Chronicle. @mannyNYT

A version of this article appears in print on

, on Page

A

9

of the New York edition

with the headline:

1 Year Later, Relief Stalls For Poorest In Houston

. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Read More | https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/03/us/hurricane-harvey-houston.html | http://www.nytimes.com/by/manny-fernandez

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover, in 2018-09-03 14:40:36

0 notes

Text

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover https://ift.tt/2PsaEO0

Nature

HOUSTON — Hurricane Harvey ruined the little house on Lufkin Street. And ruined it remains, one year later.

Vertical wooden beams for walls. Hard concrete for floors. Lawn mowers where furniture used to be. Holes where the ceiling used to be. Light from a lamp on a stool, and a barricaded window to keep out thieves. Even the twig-and-string angel decoration on the front door — “Home is where you rest your wings” — was askew.

Monika Houston walked around her family’s home and said nothing for a long time. Tears streamed down her cheeks. She and her relatives have been unable, in the wake of the powerful storm that drenched Texas last summer, to completely restore both their house and their lives. Ms. Houston, 43, has been living alternately in a trailer on the front lawn, at her family’s other Harvey-damaged house down the block, with friends and elsewhere. Outside the trailer were barrels for campfires, set not to stay warm but to keep the mosquitoes away.

What help Ms. Houston’s family received from the government, nonprofit groups and volunteers was not enough, and she remains in a state of quasi-homelessness. She pointed to the dusty water-cooler jug by the open front door; inside were rolls of pennies, loose change and a crumpled $2 bill.

“That’s our savings,” she said as she picked up the jug and slammed it down. “We’ve never been in a position to save. We’ve been struggling, trying to hold onto what we have. This is horrible, a year later. I’m not happy. I’m broken. I’m sad. I’m confused. I’ve lost my way. I’m just as crooked as that angel on that door.”

Image

Monika Houston, 43, has been living in a trailer in front of her flooded and gutted home.

Houston and other Texas cities hit hard by Harvey a year ago have made significant progress recuperating from the worst rainstorm in United States history. The piles of debris — nearly 13 million cubic yards of it — are long gone, and many residents are back in their refurbished homes. Billions of dollars in federal aid and donations have helped Texans repair, rebuild and recover.

But this is not uniformly the case, and the exceptions trace a disturbing path of income and race across a state where those dividing lines are often easy to see.

A survey last month showed that 27 percent of Hispanic Texans whose homes were badly damaged reported that those homes remained unsafe to live in, compared to 20 percent of blacks and 11 percent of whites. There were similar disparities with income: 50 percent of lower-income respondents said they weren’t getting the help they needed, compared to 32 percent of those with higher incomes, according to the survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Episcopal Health Foundation.

In many low-income neighborhoods around Houston, it feels like Harvey struck not last year but last month. Some of Houston’s most vulnerable and impoverished residents remain in the early stages of their rebuilding effort and live in the shadows of the widespread perception that Texas has successfully rebounded from the historic flooding.

In the poorest communities, some residents are still living with relatives or friends because their homes remain under repair. Others are living in their flood-damaged or half-repaired homes, struggling in squalid and mold-infested conditions. Still others have moved into trailers and other structures on their property.

One 84-year-old veteran, Henry Heileman, lived until recently in a shipping container while his home was being worked on. The container, which had been transformed into a mini-apartment with a bathroom, bed and lattice-lined foundation, was roughly 42 feet long and 6 feet wide.

The recovery has been problematic for the African-American and Hispanic families who live in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods for several reasons. The scale of Harvey’s devastation and the depths of the social ills that existed in the Houston area before the storm played a role. So did a scattershot recovery that saw some people get the government aid and charity assistance they needed, when they needed it, while others had more difficulty or became entangled in disputes and complications with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“Everything always hits the poor harder than it does everybody else,” said John Sharp, the head of the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas, which is helping to coordinate the state response to Harvey and to assist local officials and nonprofit groups.

These residents have not struggled in isolation. They have been assisted in the past year by officials and volunteers, but their repairs and recovery stalled for different reasons. Some of them no longer seek out help and suffer privately, ashamed of their living conditions but unable to move forward with their lives. Their housing issues are one of many problems they are confronting post-Harvey. Some are disabled, ill, unemployed or caring for older relatives. Some said they or their relatives are taking medication or undergoing counseling to cope with post-Harvey stress.

“In New Orleans, you could see the remnants of Katrina by the markings of FEMA spray paint on people’s homes, and you could see those waterlines,” said Amanda K. Edwards, a Houston city councilwoman who has led an effort to identify and knock on the doors of low-income flood victims who have stopped answering phone calls from those trying to assist them. “Those types of visuals are not present here. So it is difficult for people to really appreciate how difficult of a time people are having.”

Image

Amanda Edwards, 36, a Houston city councilwoman, drives through neighborhoods that were badly hit during Hurricane Harvey.

Days after the one-year anniversary of Harvey’s Texas landfall on Aug. 25, Ms. Edwards drove to the home of a victim in the Houston Gardens neighborhood. She parked in the driveway of a flood-damaged home that, from the outside, appeared in good condition. Ms. Edwards was told that the African-American man inside lives in his home without electricity. As Ms. Edwards stood on the man’s doorstep, he called out to her with the door closed, telling her he did not want any visitors.

Nearby, Ms. Edwards was given a tour of Kaverna Moore’s gutted home. Ms. Moore, 67, lived in her home for months after Harvey and finally moved in with her son in March. Her repairs stalled after she was denied disaster assistance by FEMA.

She sorted through her papers and pulled out the FEMA denial letter. It was dated September 23, 2017, and stated that she was ineligible because “the damage to your essential personal property was not caused by the disaster.” The letter baffles her. She lost her furniture, her carpet, her shoes and her appliances when about 2 feet of floodwater inundated her home. A contractor’s estimate to repair the damage to the physical structure, including replacing the sheet rock and installing new doors, was $18,605. She appealed the FEMA denial but never heard back.

She said she has no idea when she will be back in her home. She was waiting for Habitat for Humanity to work on the house.

“I miss my house,” Ms. Moore said. “I miss it a whole lot. I come by every day. Check my mail. Sometimes I come and sit on the porch.”

Image

Kaverna Moore, 67, was living in her gutted and moldy house until March, when she had to have surgery and moved in with her son.

Image

Patricia Crawford waits, too.

Ms. Crawford’s house remains under repair while she undergoes cancer treatment. Ms. Crawford, 74, went to live with a friend after Harvey. She moved back into her house — the house she grew up in — in June, before it was ready, then moved out after a few days. Her house remains a work in progress, with unpainted walls and construction padding on the floors, the rooms strewn with power tools. Her bed is still tightly wrapped in plastic.

She received some money from FEMA but was denied other assistance. So she waits, living with another friend and counting on help from relatives and nonprofit groups like the Fifth Ward Community Redevelopment Corporation.

“It’s been hard,” Ms. Crawford said one afternoon as she sat on a sofa at her half-finished house. “Have you ever felt like you were just lost? Well, that’s the way I feel. I feel lost. My doctor told me that if I didn’t stop grieving, she was going to put me in the hospital. But I’m doing better.”

Image

Patricia Crawford, 74, visits her home in the Kashmere Gardens neighborhood of Houston.

No local, state or federal agency has been tracking how many people remain displaced after Harvey. It is unclear how many residents are struggling to complete repairs or have had their recovery stall. In the Kashmere Gardens section of northeast Houston — the low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhood along Interstate 610 where Ms. Houston and Ms. Crawford live — Keith Downey, a community leader, estimated that at least 1,500 Harvey victims in the area were not back in their homes.

In the Kaiser and Episcopal survey, based on phone interviews with more than 1,600 adults in 24 Harvey-damaged counties in June and July, three out of 10 residents said their lives were still “very” or “somewhat” disrupted from the storm.

The race and income disparities identified in the survey are likely a result of what existed before the storm, said Elena Marks, president and chief executive of the Episcopal Health Foundation and a former health policy director for the city of Houston. “If you went into the storm with relatively few resources, and then you lost resources, be it income or property or car, it’s going to be harder for you to replace it,” she said. “The farther behind you were before the storm, the less likely you are to bounce back after the storm.”

Local, state and federal officials expressed concern for low-income Harvey victims, but they were unable to explain why so many of them continue to struggle. City officials say there has been no shortage of resources and services for poor residents affected by the storm, including the 14 neighborhood restoration centers the city opened, mostly in low-income areas. FEMA said it has put $4.3 billion into the hands of affected Houstonians.

“There are thousands of families who live in low-income communities, who already were operating at the margins before Harvey, and the storm pushed them down even further,” the mayor of Houston, Sylvester Turner, said in an interview. “We want to reassure them that they have not been forgotten.”

Mr. Turner, who visited Kashmere Gardens and other neighborhoods to mark the anniversary of Harvey, described the problem as a federal and state issue, citing the $5 billion in federal Community Development Block Grant disaster-recovery funds that were approved for Texas, but that Houston has yet to receive.

“We know that the city is going to receive $1.14 billion dollars in C.D.B.G. funding for housing,” Mr. Turner said. “But you can’t disperse what you don’t have.”

Kurt H. Pickering, a spokesman for FEMA in Texas, said the agency had seen no evidence that low-income areas were receiving less support from the agency. He said that federal assistance was designed not to make a person whole after a disaster, but to help start the recovery process. “FEMA does everything possible to assist every family in every way,” within the bounds of its regulations, Mr. Pickering said.

In Kashmere Gardens, Ms. Houston ended the tour of her house on Lufkin Street after a few minutes.

“I can’t stay in here too long because I start coughing,” she said.

She spoke of the past 12 months as a series of disputes and broken promises. She said she felt abandoned by FEMA, contractors, reporters and celebrities who visited the neighborhood and failed to follow up on repairs. “We’re no more than 15 minutes from River Oaks,” she said, referring to one of the wealthiest areas of Houston. “It’s not just the government. Don’t nobody care.”

Ms. Houston, a former truck driver, walked to the middle of Lufkin and turned around to face the house. The yard with the trailer was cluttered, but the house appeared normal.

“When you stand here, you would never know what lies behind those walls,” she said. “Look at it. You don’t even know how broken it is. That’s the sad part.”

Image

A portrait of Patricia Crawford’s parents still hangs in her home, although she is unable to move back.

Michelle O’Donnell contributed reporting from Houston.

Manny Fernandez is the Houston bureau chief, covering Texas and Oklahoma. He joined The Times as a Metro reporter in 2005, covering the Bronx and housing. He previously worked for The Washington Post and The San Francisco Chronicle. @mannyNYT

A version of this article appears in print on

, on Page

A

9

of the New York edition

with the headline:

1 Year Later, Relief Stalls For Poorest In Houston

. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Read More | https://ift.tt/2wz3ctK | https://ift.tt/2wFyRtg

Nature A Year After Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s Poorest Neighborhoods Are Slowest to Recover, in 2018-09-03 14:40:36

0 notes

Text

Task 1: Where do I live?

I’ve lived in many communities over the past few years, I’ve linked my families nomadic tendencies to our mostly first generation immigrant status. The person in charge of all the major stuff i.e. our survival would be my dad due to my father’s continuous status of being the biggest portion of my families revenue. My family is led by a patriarch like most of the families in today’s Western society a trend which is changing. My father is in charge of every decision made for the benefit of my 5 person blended family constituting my Step-Mother, Step-brother, Half-Brother, Dad and I. I moved around a lot while I was growing up, 4 times to be exact, 3 times in high school, within these different communities there were many similar traits as well as differences within the individual communities that molded me into becoming the person I am today.

Coming from another country, Jamaica, my dad and I came to Canada with the hopes of socioeconomic prosperity like most immigrants to the humble home of my Step-Mother. It was located in a really bad neighborhood, by the name of Notre-Dame-de-Grace in Montreal, Quebec. This community was actually filled with other new immigrants trying to move up the socioeconomic pyramid as well with entry level job’s like my dad. Luckily, Notre-Dame-de Grace had a population of mostly English Speaking citizens so it wasn’t difficult to integrate, but on the other hand I was forced to attend a fully French school where I suffered educationally, because of the lack of sympathy and patience beyond the 1.5 years of “welcome class” or “accueille”. In the end of grade 5 and grade 6 i received the nearly 2 frustrating years in which I wasn’t taught much standard math or science because I couldn’t speak or understand the language. Teachers were only focused on teaching me how to be as French Canadian as possible. Montreal’s school system didn’t have much sympathy or patience for immigrant kids with non-french backgrounds, but I made it work somehow, graduating from elementary school. I tried entering an English High-School but wasn’t granted permission because of strict admission laws. I was forced into entering a fully French High-School and not the “special” High-school the unfortunate few who didn’t excel became students of due to the disturbingly huge language barrier faced by the “accueille kids”. Eventually this became a cultural barrier and I saw my fellow classmates from elementary school being ridiculed for a lack of education caused by a faulty educational system. I ended up leaving Montreal in Grade 9 because my father had finally gotten an opportunity to become a supervisor at another store in Ontario, where My siblings and I could pursue a greater education and where my step-mother a first generation immigrant, as I am could go back to school. Now, through observation I witnessed that most of my monolingual French classmates attended post secondary institutions while the majority of my “accueille” classmates entered the working class, full-time, right after High-School.

After moving to Hamilton I was finally at the school of my dreams, a French-Immersion school in which I could learn to the best of my abilities in both English and French. It was also in that school where I picked up academic courses, in which I could finally complete my school work in a reasonable amount of time and without much hassle allowing me to be confident in myself. I learned how to socialize at a much more effective degree through my community, where I became involved at the community center, playing basketball on the weekends with the kids in my lower-class neighborhood. But mostly at school where I could develop relationships with a wider range of students as well as teachers due to the elimination of the language barrier I faced in Montreal. I was able to become apart of my school’s community even more by joining the school’s football team and representing them at games. My experiences in Hamilton taught me a lot about Canadian culture and enabled me to enjoy the integration process immigrants face rather than the forced assimilation by the government of Quebec. Through education I was also enlightened on the darker side of Canadian as well as North American culture stemming from oppression, apartheid and xenophobia, faced by my fellow black people. This helped me develop a cultural identity, one that I could finally call my own this was the beginning of the end of a quest of integration that I and many other black immigrants in my community had to face. At school I also became aware that most minorities lived in or near my lower class neighborhood, I also witnessed higher homicide-rates and drug-addiction rates compared to the middle and upper class neighborhoods around my city in which most of my Caucasian friends inhabited. Sadly I even got the chance to witness racism and the pleasure of enduring some of it, once having a young man once tell me he was surprised I could get a better grade in math than he could because of my ethnicity. But although there were some rocky times in Hamilton, I couldn’t have become the person who I love today without the experiences acquired from the teachers, students and the members of my community.

Presently, I live in Mississauga making it the school in which I finished my last year of High School resulting a victory lap. The city of Mississauga is the city in which I went to prom, found a girlfriend, bought a car and am presently trying to get into University, The culmination of everything in my life has led me to this city. I am now in the early stages of adulthood and through a few online courses I’ve been able to become even more educated on societal matters as well as develop a more informed worldview. I still live in a low income building, but my neighborhood is better I can still see evidence that those from immigrant backgrounds make up the majority of the people living in my lower-class apartment complex as well as the one beside me. In certain cases those who’s families have been here for more than a generation are still socioeconomically stagnant, I believe this has come from a cycle entailing a lack of opportunities for past generations of visibly minority immigrants to be enrolled in post-secondary institutions, due to xenophobia and racism. Because of a neighborhood in which there are some middle-class families and the rare upper-class families on the outskirts I’ve had a chance to interact with people of a higher socioeconomic status and many people who aren’t visible minorities with 45.8 percent of the population identifying as non-visible minority, including my friend's dad, a business owner who showed me how to do my taxes rather than have to pay hundreds to get it done. In turn I was able to help all my friends who lived in my lower-class area to do their taxes and hopefully have them in turn teach someone from their group, mostly constituting lower-class young adults to do their taxes. Living in a better neighborhood where the effects of poverty were less prevalent gave me opportunities that I didn’t have before due to the socioeconomic rift between the rich and the poor in the neighborhoods in which I had resided previously. It was also easier to find an entry level job for an aspiring student such as myself because of all the local businesses that were willing to hire me which weren’t present in Hamilton. The lack of a forced language barrier such as the french one in Montreal also facilitated my success. These opportunities allowed me to purchase a car and acquire another job which in turn will help me pay for university. Successfully breaking the cycle that many visible minority immigrants have to be apart of.

The neighborhoods in which I have lived in thus far in Canada haven’t changed much in the last few years according to recent census research. The data gathered to make these points were gathered in 2016 for Montreal, 2011 for Mississauga and in 2015 for Hamilton. I have been in each of the 3 cities explored in previous paragraphs in the past year and the data gathered from the “Statistics Canada” website as well as the data acquired from “The City of Montreal” website during those 3 separate years accurately reflect the demographics consisting of the socioeconomic status, ethnic diversity, and crime rates of these cities in the present day to a veracious degree. The debate of nature vs nurture is one that scientists still can’t fully grasp, the question asking if rather than our genetics we are products of our environment is one that has no concrete answer for now. Although my experiences in these different neighborhoods have led me to believe that if I hadn’t been exposed to all three communities throughout the entirety of my childhood I would have been a completely different person today

0 notes

Photo

The AlexWorldClub interview

By Dimitra Moutzouris

Alexandra Gravas, a European with a Greek heart!

Alexandra Gravas was born in Offenbach, a small German city on the south side of the river Main, Frankfurt, but her family roots go back to Asia Minor. Her parents were immigrants from Greece and Alexandra grew up under the influence of two different cultural environments, by the melodies of Greek songs at home and with German classical music at school. Maybe that is why in her ten years career Gravas seeks to create cultural bridges threw her work and refuses to restrict her voice into one music style. Her repertoire is impressively wide (opera roles, oratorio solos, classical, traditional and contemporary song, poetry set to music ) and she had successfully performed all over the world (Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Belgium, Austria, Holland , Spain, Israel, Sweden, Cyprus, Hungary, Italy, USA, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Malaysia, Japan). The professional success and international recognition that Gravas enjoys today are only results of her hard work and persistent effort. She was sixteen years old when she lost her voice due to a disease in her vocal cords, but her health adventure, lasted two painfully silent years, had only made her passion for singing stronger. After finishing her studies in Musicology, German Literature and Philosophy at the Goethe University of Frankfurt, Alexandra studied song next to the renowned teachers Loh Siew Tuan and Vera Rosza in London. In 2002 she made her debut at the City Opera of London, where she remained for three years, and at the same time she worked with Mary King in the English National Opera Studio. She has premiered works of internationally acclaimed composers such as Mikis Theodorakis, Demosthenes Stephanidis, Mimis Plessas, Alexandros Karozas, Francis James Brown, George Tsontakis, Achim Burg, Harue Kunieda, Constantine Caravasilis, Dante Borsetto, Jonnusuke Yamamoto, Otto Freudenthal and her recordings of “Bitter Tears” by Demosthenes Stephanidis had won the first prize of the 2004 Tomos Contemporary Music Editions Prize Competition in the USA. Restless spirit and creative soul Gravas has been actively involved in the production of her music projects. She is the founder and leader of the London based orchestra Orama Ensemble, while together with Dr. Pantelis Polyxronidis and Prof. Vasilios Lambropoulos conceived the ‘C.P.Cavafy in Music, a recital of songs and reflections’, an international music project that she had successfully performed in Europe and USA. Alexandra Gravas represents through her work Greek music, poetry and soul all over the world. In 2004 she had been invited to give the final concert, that marked the closing of the prestigious Frankfurt Book Fair, at the Alte Oper of Frankfurt, and in 2007 she appeared at the opening recital of the famous London Song Festival accompanied by its founder, pianist Nigel Foster. In December of 2013 the tenor Plácido Domingo invited her to sing at an event at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Gravas has a strong sense of social responsibility and had generously served with her voice several charity causes such as the Greek SOS Children’s Villages, the Doctors without Borders and the 12 Hours for Greece Project. Today she is the cultural ambassador of the Greek island Rhodes for its nomination for the title of the European Capital of Culture of 2021. A role that suits perfectly to her. After all, the mezzo soprano identifies herself as ‘a European with a Greek heart’!

Meet the Artist:

1. Which were your first musical hearings and what kind of music have you grown up listening to? My mother and my father were always singing at home or while driving the car. Singing was a very natural thing to us all in the family, although nobody ever had studied music except me later on. Both of my parents had very good and versatile voices and I remember how fascinated I was listening to them. As a teenager I was listening to anything ‘en vogue’ at the time…I was (and I still am) a huge ABBA fan. 2. You come from a family with no professional relation to music. When did you first realize your talent in singing and what emotions did that realization caused you? As my mother told me later on, I was always singing. Nobody told me to. Singing was just natural to me! I was able to immediately copy melodies and to sing them correctly. Once that had been discovered in kindergarten and later in school, I realized that I somehow could turn all the attention of my friends and surroundings to me…how great was that! It made me feel like a princess. I guess a child can feel the admiration as much as an adult. I realized that with my voice people would be nicer to me and put me to a privileged position. 3. At the age of 16 you have ‘lost your voice’ due to a pharyngitis disease and you remained silent for almost two years. Where did you draw strength to carry on your efforts for a career in singing? Strength comes from within, when you don’t know that it has to come from there…The only thing I knew was that there was no way I would not become a professional singer. Although there had been a handful of stupid doctors at the time, who told me, that I would not be able to ever sing again and even speak properly, I was convinced that I would be healed and sing again. In those years the process of discovering my body and soul had been fully active. I was entering new worlds of self-consciousness, various “why me”. My self-healing efforts accompanied with the help of a great phoneatric doctor, who had finally diagnosed my vocal problem and found the cure, led me to the path of healing. Looking back today, it could have not been differently. 4. Do you believe that classical music or poetry set to music requires a well educated audience in order to be understood and appreciated? No! What does it mean to be “understood” and “appreciated”? These words belong to musicologists. Full stop. I refuse to go to this path of thinking. When I first listened, at the age of 12, to the Greek song “Sto Perigiali/At the sea shore” by the Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis, I was fascinated. I could not understand a word of the Greek lyrics…I was a little girl then, born and raised in Germany with no Greek school education. I did not know that Theodorakis had set the wonderful poetry of the Greek noble prize winner George Seferis into Music. It was the song that made me want to understand Greek, to sing Greek and since then, it is the love of my life! Let’s get back to our senses and trust them. The Ear hears and the Heart feels…Music is the key to opening up the heart. Whether classical or not, traditional or pop, if music has something to tell you, then the intellectual borders lose their place.

5. From opera songs to Madonna’s Frozen you seem to move with remarkable convenience through different music styles. Do you have any special preference? Where do you feel most ‘at home’? I am truly interested in many music styles and I am always looking for the next challenge. Singing for me is not just interpreting but creating something. Creation is a part of me. My family roots come from Asia Minor. It seems they have inflicted on my DNA lots of their musical preferences. The Greek language and its songs are “home” to me. 6. Is Music an international language? Thank God that music is universal and will always be as long as it comes from the heart. No matter if it is sung in Mexico or in Athens. 7. You have participated in several charity concerts. Have you ever felt that talent comes together with a responsibility? I would not talk about responsibility. For me it is a ��human must’ to help when I can. To combine your art with helping is a wonderful thing. Putting people together for a good cause and being a part of it, is indeed special. I have given, but at the same time I have received back lots! 8. Which have been the most exciting or touching moments in your ten years career so far? My first professional Liederabend in the Mozart Saal of the Alte Oper Frankfurt, where people who knew me from the “silent phase” saw me sing for the first time. Pure emotions! 9. People tend to believe that talent is the only prerequisite for success. What advice would you give to a young artist? Find the best teacher in your field to teach you and work very hard. Learn the required technique and what your teachers want from you. Never stay to long with them. And then break out of the educational cave of the past and try to find your own path and your own creative world. That in particular needs courage…Tons of courage! 10. What’s your favorite song at the moment or the song you listen on repeat? At the moment it is my 5 years old son’s favorite song from “Lillypoupouli”and it goes like that: “to hondro bizeli horevi tsifteteli, horevi tsifteteli sto horo ton bizelion”.

Living in Greece:

1. You have recently moved with your family to Athens, Greece, at a very difficult financial and social period for the country. What has led you to take that decision? My mother died and I came to Greece to organize what needs to be organized. It took longer than I thought and I stayed longer and longer. So now I have decided to stay a little bit more. It is time to discover my motherland. 2. What do you love most / less about living in Greece? I love the sun and the heat! I discover something new every day. Greece is like a candy store with much to taste… sweet and sour. 3. Do you believe that Athens is a creatively inspiring city? Greeks are very talented people…I meet them all the time! The musicians are of the finest here in Athens and I love to work with them.

You have been travelling with your voice Greek music, poetry and soul all over the world. What is the dominant picture of modern Greece abroad right now and in what ways could we improve it? I have been very lucky to travel the world with what I love doing most: performing my own projects. They are my babies! I have been welcomed with overwhelming love from my audiences everywhere spanning the globe, from Tokyo to Mexico. People are interested to discover new horizons, which I offer them with my performances. I always try to combine the Greek culture with the cultures I am visiting in order to make my Greek concert themes accessible to non-Greek speakers. It is about making cultural bridges and the result has to be always a creative challenge!

0 notes