#leatherstock

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

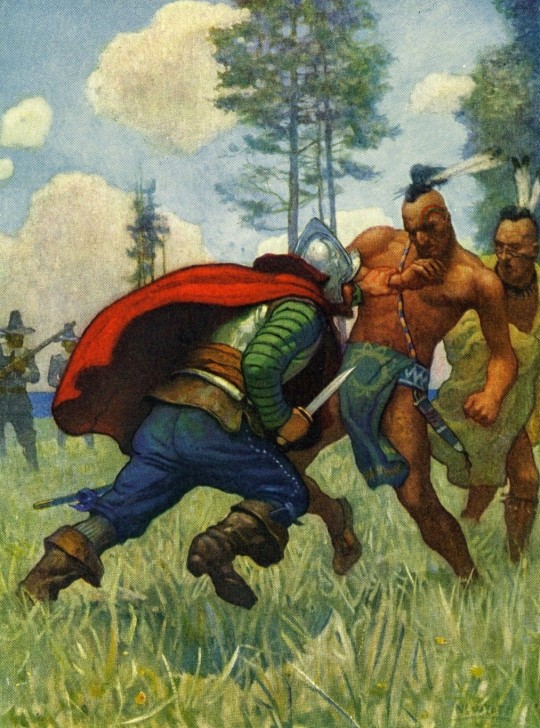

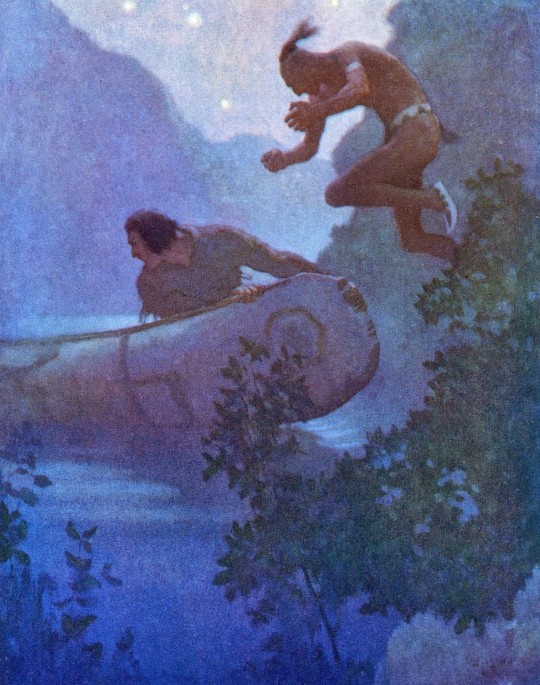

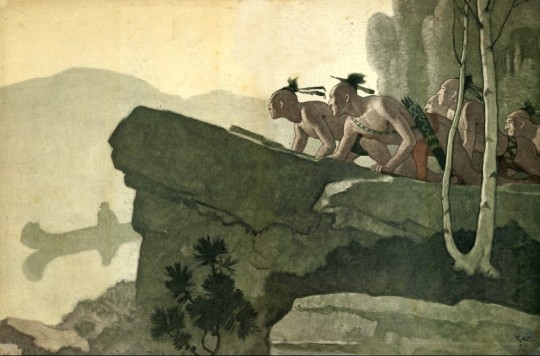

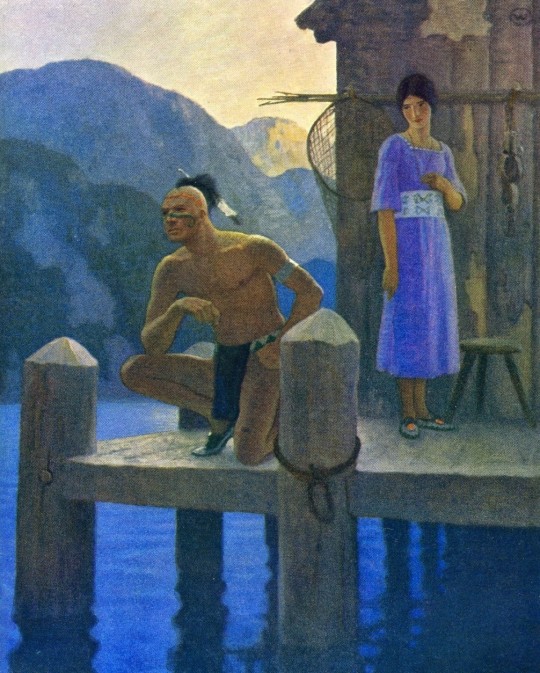

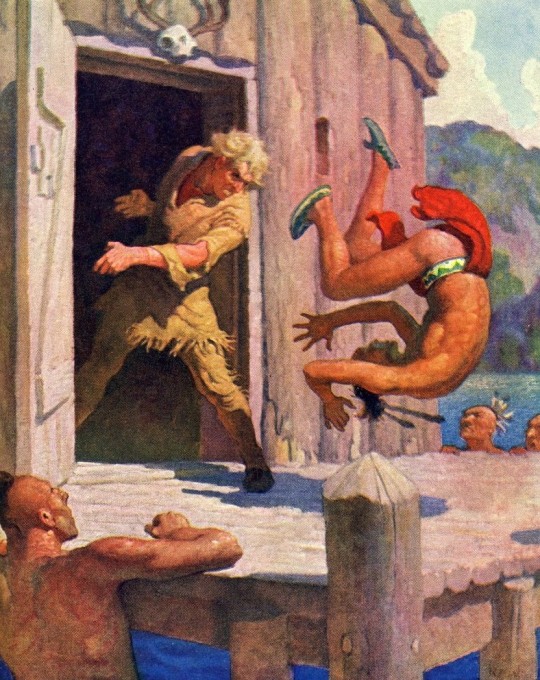

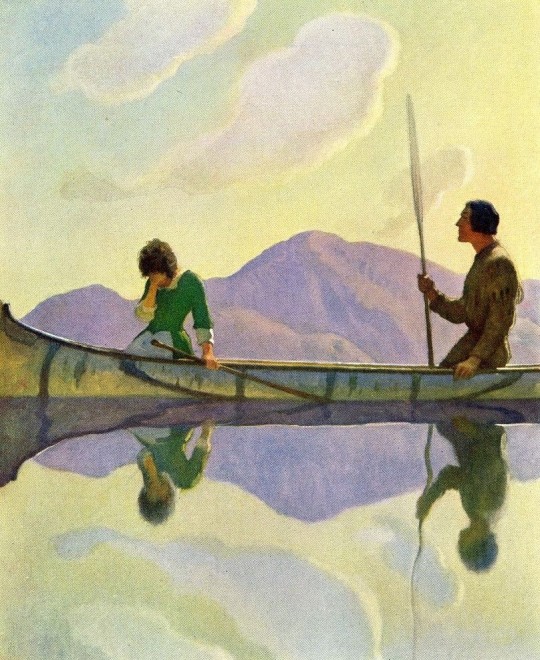

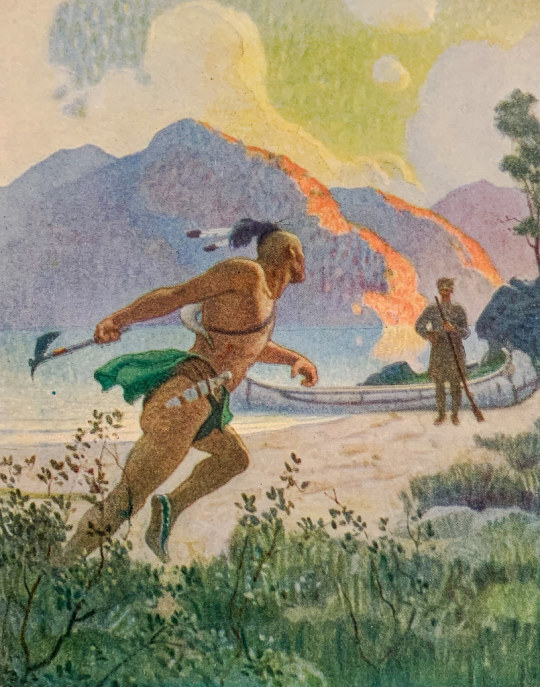

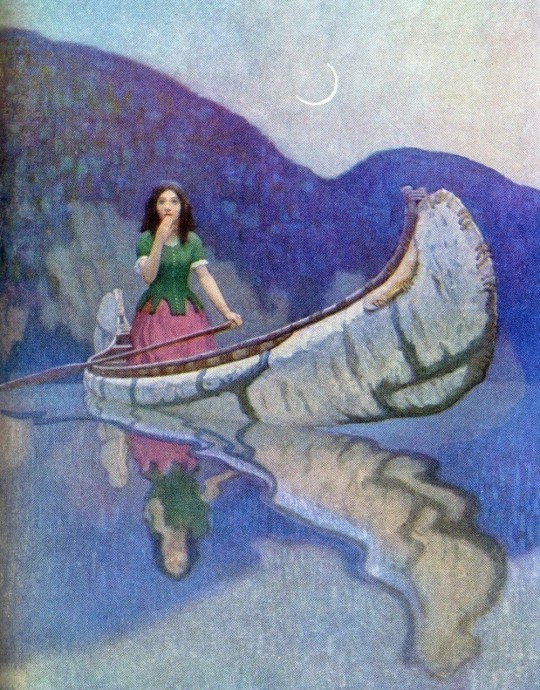

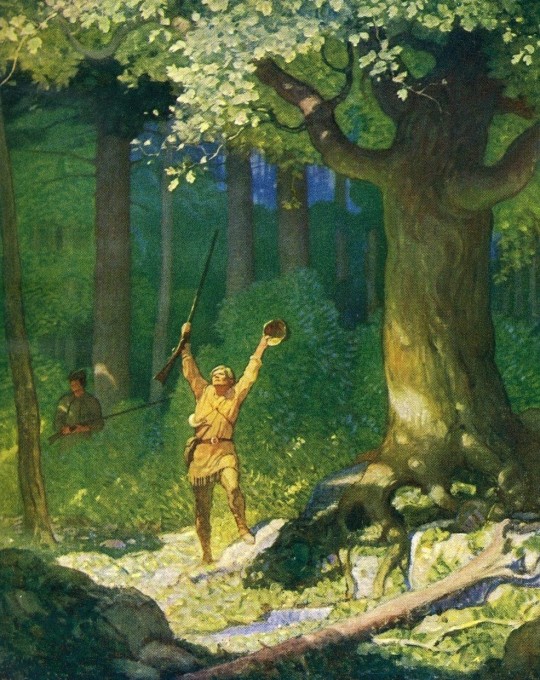

The Deerslayer - art by N. C. Wyeth (1925)

#n. c. wyeth#the deerslayer#james fenimore cooper#book illustrations#adventure novels#leatherstocking tales#nathaniel bumppo#hawkeye#charles scribner's sons publisher#1920s#1925

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do American authors still write pages of one unbroken paragraph or was that more a 19th century thing? Either way, I hate it.

#henry james#james fenimore cooper#american authors#american literature#literature#books#leatherstocking tales#the pioneers#reading#booklr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm just saying, but I feel like the opening page for the Marvel Classic Comics adaptation of "The Last of the Mohicans" looks better than any poster, VHS, DVD or Blu-Ray cover for any screen adaptation. I also love how Chingachgook, who ultimately turns out to be the title character, is the American Indian character who we are drawn to first while his son Uncas, whom we are led to believe is the title character, is basically tucked away in the corner there with Cora. Then you have Hawkeye aka Leatherstocking, the protagonist of the Leatherstocking Tales as a whole, placed behind Chingachgook and that is a nice touch and does a better job than most screen adaptations, especially the 1992 film, whose posters and covers feature the protagonist, but not the title character, while here both title character and protagonist are present.

0 notes

Text

✨️obligatory 2022 reading log ✨️

yes i did give up on rating half-way through the year 💛 it's fine 😌

#i meant to read more but cooper was such a goddamn slog#and no one was making me finish it#but momma didn't raise no quitter#shout out to rae for putting up with my leatherstocking grumbling for 4 months 😬

1 note

·

View note

Text

[“A deep psychosis inherent in US settler colonialism is revealed in settler self-indigenization.

The phenomenon is not the same as the practice of “playing Indian,” which historian Philip Deloria brilliantly dissected, from the Boston Tea Party Indians to hobbyists dressing up like Indians to New Age Indians. Settler self-indigenization’s genealogy can be traced to the period of the mid-1820s to 1840s, what historians call the Age of Jacksonian Democracy, marked by, among other phenomenon, the blossoming of US American literature.

The giants of the era are well known to every US high schooler who has had to suffer through American Lit classes—Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman, Longfellow, Hawthorne, and dozens of others. Among them was James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851), who conjured the United States’ origin story in his Leatherstocking Tales, made up of five novels featuring the hero Natty Bumppo, also called variously, depending on his age, Leatherstocking, Pathfinder, Deer-slayer, Hawkeye. Together the novels narrate the mythical forging of the new country from the 1754–1763 French and Indian War to independence to the settlement of the plains by migrants traveling by wagon train from Tennessee. At the end of the saga, Bumppo dies a very old man on the edge of the Rocky Mountains as he gazes east. But it is The Last of the Mohicans, subtitled A Narrative of 1757, that relates the self-indigenization myth that has endured. The Last of the Mohicans was a best-selling book throughout the nineteenth century and has been in print continuously since, along with a half dozen Hollywood movies, the first in 1911, plus several television series made in the US, Canada, and Britain. The most recent Hollywood production was a blockbuster that appeared in 1992, the Columbus Quincentenary.

Cooper conjured the birth of something new and wondrous, literally, the US American race, a new people born of the merger of the best of both worlds, the Native and the European, not a biological merger but something more ephemeral involving the disappearance of the Indian. Cooper has Chingachgook, the last of the “noble” and “pure” Natives, die off as nature would have it, handing the continent over to Hawkeye, the indigenized settler and Chingachgook’s adopted son. The publication arc of the Leatherstocking Tales parallels the Jackson presidency. For those who consumed the books in that period and throughout the nineteenth century—generations of young white men mainly—the novels became perceived fact, not fiction, and the basis for the coalescence of US American settler nationalism, the settler ideology that justified the fiscal-military state.”]

roxanne dunbar-ortiz, from not a nation of immigrants: settler colonialism, white supremacy, and a history of erasure and exclusion, 2021

#roxanne dunbar ortiz#lesbian literature#history stuff#cw genocide#essential for understanding American literature and ESPECIALLY American fantasy literature

127 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Old Leatherstocking - O Death (Conversation With Death)

21 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Old Leatherstocking - Death and the Lady

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#QSLfriday WRUN signed on April 24, 1948, under the ownership of the Rome Sentinel newspaper. The Sentinel was concerned that local radio did not adequately serve the Utica-Rome area. WRUN, with a 5,000-watt signal, had a more regional reach.

One of its announcers during WRUN's early days, in his first job as a broadcaster, was a young radio announcer named Dick Clark, whose father was the manager of WRUN. He was known on-air as "Dick Clay," to avoid confusion with his father, who had the same name. The young Dick Clark would move to television, as anchor of the evening news program on WKTV, in 1951.

The station became WUTI in 2008 and was last owned by Leatherstocking Media Group, Inc. It was simulcast with WFBL in Syracuse until it went off the air in 2013.

Committee to Preserve Radio Verifications | Tumblr Archive

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Was The Real Calamity Jane? Historians Search For An Answer.

Her exploits became the stuff of legend, glamorizing life in the Old West. But Martha Jane Canary’s real life story bears little resemblance to the fictional heroine.

— By Heather Mundt | March 12, 2024

Calamity Jane — Born Martha Jane Canary — Is a Legend of the American West. But was she a gunslinger? An Army scout? A rider for the Pony Express? After a century of half-truths and fabrications, historians are still struggling to separate fact from fiction in her life story. Photograph By Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images

You would be forgiven in describing Calamity Jane as an iconoclast whose flouting of 19th-century female mores launched her into exceptional fame and fortune in a male-dominated American West.

It’s true the woman behind the fictional heroine—born Martha Jane Canary—was a buckskin-clad, gun-slinging, foulmouthed cowgirl whose affinity for alcohol was legendary, even among men. But that’s where facts diverge significantly from fiction.

Historians have spent decades trying to find her—methodically unraveling a century of mistruths, half-truths, and full-blown fabrication, many of them introduced by Calamity herself. She was also illiterate, leaving no letters or journals for analysis, not even a signature. So who was the real Calamity Jane?

The Creation of a Myth

“People, largely, are still in love with a romantic Old West," says Richard W. Etulain, former director of the Center for the American West at the University of New Mexico who’s written two comprehensive books on Martha Jane Canary.

It's been part of the country’s literary tradition from its inception around the early 19th century, he says. James Fenimore Cooper created the early framework for the Western as a genre in his groundbreaking Leatherstocking Tales, a five-novel frontier series that includes his famous 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans.

These were masculine stories featuring females as love interests, providing a formula for the early paperbacks called dime novels. Emerging around the start of the Civil War, the cheaply printed books sold on newsstands for no more than a dime.

With simple plots placing a hero or heroine in a dilemma, they were the perfect vehicle to spread myths about the real-life personalities of the American West—including Calamity Jane.

A Calamitous Early Life

Born around May 1, 1856, near Princeton, Missouri, Martha Jane Canary was the oldest of three children. Around 1863, the family sold their farm and headed west toward Montana, ostensibly drawn by the booming mining towns.

She told of the five-month overland journey in her autobiography, Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane, a rare kernel of truth in what’s considered an exaggerated work of semifiction.

“I was at all times with the men when there was excitement and adventures to be had,” she said. “By the time we reached Virginia City, I was considered a remarkable good shot and a fearless rider for a girl of my age.”

The Trek Ended in Heartache.

Both of her parents died within four years of the move and, by 1867, her siblings were allegedly sent to live with Mormon families in Utah. Not yet a teenager, Etulain writes in The Life and Legends of Calamity Jane that she was adrift in a pioneer man’s world.

Calamity Jane lived a nomadic life, taking jobs for a few weeks at a time before heading to the next spot whim took her. And that’s where her story begins to blend into myth.

Dime Novel Fame

By the time she’d reached age 20, Martha Canary was already well known in the “rough and ready settlements of the western plains for dressing in men’s clothes, a taste for liquor and wanderlust, and a tendency to shoot off her mouth and her guns,” writes historian Karen R. Jones in The Many Lives of Calamity.

Tthe genesis of her nickname is unclear. What is clear is that she was already known as Calamity Jane in the summer of 1876 when she sauntered down the dusty main street of Deadwood, South Dakota, on horseback in a suit of buckskin alongside Wild Bill Hickok.

Calamity Jane gained fame in the 1870s after arriving on horseback in Deadwood, South Dakota, alongside Wild Bill Hickok. The two were likely mere acquaintances but dime novels and sensational newspaper stories published many a tall tale of their dubious exploits together. Photograph By Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images

She was traveling with the most famous gunman and lawman of the West, Etulain writes, having joined his wagon train of gold seekers as it headed north toward the Black Hills.

“Calamity Jane has arrived!” local newspapers proclaimed. From that moment, her name would be intertwined with Wild Bill’s in Old West lore. The news stories that followed, embellished and sensationalized in the era of yellow journalism, flung her into stratospheric fame.

She would be forevermore the wild woman of the West, often cast in dime novels as the love interest of notorious gunslinger Wild Bill. She was also often linked with another famous Bill—Buffalo Bill Cody, whose prowess in slaughtering buffalo had become dime novel legend. Stories abounded of her performances in his famous stage show, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

In her semifictional 1896 autobiography Life and Adventures of Calamity, Calamity also described herself as a rowdy plainswoman who rode for the Pony Express and served as General Custer’s scout.

For more than a century that followed, the depictions of Calamity Jane in media would make it even more difficult to unravel the truths of her life. In Cecil B. DeMille’s 1936 movie The Plainsman, she was a rip-roaring cowgirl who fought Native Americans alongside Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill. Some 70 years after that she was portrayed as the bawdy friend of Wild Bill and town drunk in HBO’s Western series, Deadwood.

The Real Calamity Jane

Many of the tall tales surrounding Calamity’s life are rooted in fact.

She may have served as an Army scout, her biographers found—just not for General Custer. Calamity did know Wild Bill, but not as his romantic partner. In fact, they would have been little more than acquaintances. (Hickok was assassinated at a poker game shortly after the group’s arrival in Deadwood.)

Calamity Jane was also cast in traveling shows but not Buffalo Bill’s Wild West production, says Jeremy M. Johnston, the Tate endowed chair of Western history at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, which houses what’s believed is her only remaining buckskin suit.

She was legally married once in 1888 but did shack up with several men whom she called "husband” along the way. She also gave birth twice: first in 1882 to a son, who died shortly after his birth, and in 1887 to daughter, Jessie Elizabeth. (However, whatever happened to her daughter remains debatable.)

Tales recounting Calamity’s nursing skills are also well-documented. “She really took care of anyone who was sick,” Johnson says. “Anyone who needed anything, she would step up and help them through their troubled times.”

Johnston’s own grandmother used to tell the story of Calamity Jane helping their family recover from an illness. To thank her, his great-great grandmother made Calamity a nice shirt. A few days later, however, onlookers found her in the streets intoxicated with the shirt covered in mud.

The Death of Calamity Jane

In fact, alcoholism was constant refrain throughout her life, McLaird writes, perpetuating her lifelong poverty. “Sadly, after romantic adventures are removed, her story is mostly an account of uneventful daily life interrupted by drinking binges,” he writes.

For the last seven-plus years of her life, Etulain writes in Life and Legends, she earned money as a performer and roaming saleswoman, peddling her autobiography and photos.

Calamity Jane poses at the grave of Wild Bill Hickok in Deadwood, South Dakota, in this photograph taken by J.A. Kumpf circa 1903. The famous gunslinger died that year and was buried in the same cemetery. Photograph By Graphicaartis, Bridgeman Images

She died penniless at age 47 on August 1, 1903, likely from effects of alcoholism. She’s buried near Wild Bill in the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood—and the misinformation that pervaded her life has followed in her death, Etulain writes, as even her tombstone displays an incorrect name, birthdate, and age.

But though her real life may have been more tragedy than adventure, Etulain argues that she remains an illuminating example of grit and determination.

“The loss of her parents before her teen years, the lack of education, and the downward push on many frontier women in the late nineteenth century—Calamity rose above these challenges as a young woman of energy, endurance, and fortitude.”

#History#Historians#Search | Answer#The Real Calamity Jane#Myth Creation#Early Life#The Death | Calamity Jane#Old West#Cowboys#Legends#Mythology#Women#History & Culture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS is the kind of stuff I was looking for in the old German film mags!

LEATHERSTOCKING (1922)- And that's Bela Lugosi as Chingachook!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

📘𝐃𝐔𝐒𝐓𝐈𝐍𝐆 𝐎𝐅𝐅 𝐓𝐇𝐄 𝐂𝐎𝐕𝐄𝐑📘: Thursday – January 17, 2017 – The Deerslayer

0 notes

Text

i love the leatherstocking tales, have since i read them at 11, and i havent read them in years. started the audiobook for deerslayer and uhhhhh. well. so far its been an hour of "well this is so beautiful, it proves theres a god" "yeah well [racism]" "hold on now, god made everybody the way he made them and also morality is defined by your culture" "[racism] [lust]" "okay but have you considered that theres good and bad people everywhere and saying any specific race is bad or stupid is equivilent to spitting in gods face" "[atheism]" "look. we're white, which means its traditional to believe in god. the tribes dont believe in god but thats because theyre not white so its okay, its not their tradition. but you and i are white so we're gonna believe in god and fucking well like it"

#leo.txt#god. its sooooo#natty bumpo is so fun though#hes like yeah ive never killed a man. im not an asshole<3 and his buddy goes well IM not an asshole and i like killing people. i do it all#the time. sooooooo

1 note

·

View note

Text

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was a prolific and popular American writer of the early 19th century. He is best remembered as a novelist who wrote numerous sea-stories and the historical novels known as the Leatherstocking Tales, featuring frontiersman Natty Bumppo. Among his most famous works is the Romantic novel The Last of the Mohicans, often regarded as his masterpiece.

I Write Like

0 notes

Text

Watch Old Leatherstocking - Death and the Lady on YouTube Music

youtube

0 notes