#law of 22 prairial

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What is the whole story of the law of 22 prairial? Who wrote it in the first place? Because I've learned that Georges couthon is the one who wrote it and not robespierre so I just wanna know everything and the background of this.

Tell me about it if you can, and what was the consequences of that law that came after?

The law of 22 prairial has always been a hot topic of debate for historians, both when it comes to who exactly worked it out, as well as what the intended and actual consequences for it were.

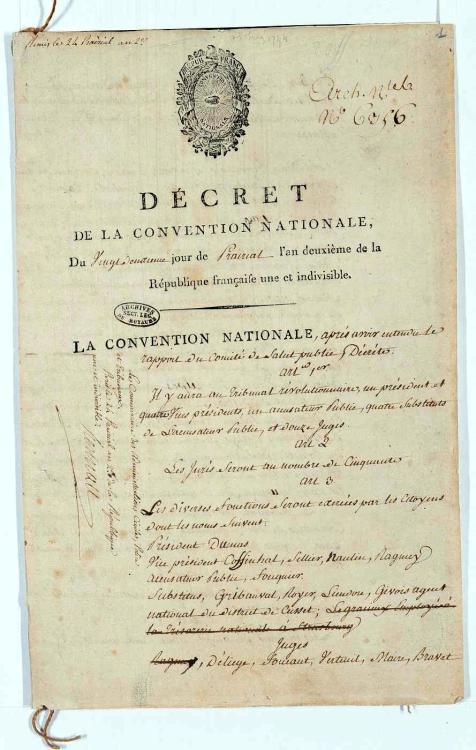

If we start with the first of these questions — who was involved in the creation of the law? — it can be observed that the draft of it is in Couthon’s handwriting. This makes him the only person where any direct involvement in the development of the law can be truly established.

Today, this draft is apperently being kept at AN C 304, pl. 1126 et pl. 1127.

The law of 22 prairial does however share several undeniable similarities with the instruction decree for a commission at Orange, written on May 10 1794, exactly a month before Couthon’s draft was presented before the Convention. Below are the relevant extracts:

The decree for the commission at Orange

The duty of the members of the commission established at Orange is to jugde the enemies of the revolution.

The enemies of the revolution are all those who, by any means whatsoever and with any deeds they may have covered themselves, have sought to thwart the march of the revolution and to prevent the strengthening of the Republic.

The punishment for this crime is death.

The evidence required for the conviction is all information, of whatever nature, which can convince a reasonable man and friend of liberty. The rule of judgments is the conscience of judges enlightened by the love of justice and of the fatherland. Their goal, the public health and the ruin of enemies of the fatherland.

Law of 22 prairial

The Revolutionary Tribunal is instituted to punish the enemies of the people.

The enemies of the people are those who seek to destroy public liberty, either by force or by cunning. [there then follows a list of eleven actions that will deem you an enemy of the people]

The penalty provided for all offenses under the jurisdiction of the Revolutionary Tribunal is death.

The proof necessary to convict enemies of the people comprises every kind of evidence, whether material or moral, oral or written, which can naturally secure the approval of every just and reasonable mind; the rule of judgments is the conscience of the jurors, enlightened by love of the Patrie; their aim, the triumph of the Republic and the ruin of its enemies; the procedure, the simple means which good sense dictates in order to arrive at a knowledge of the truth, in the forms determined by law.

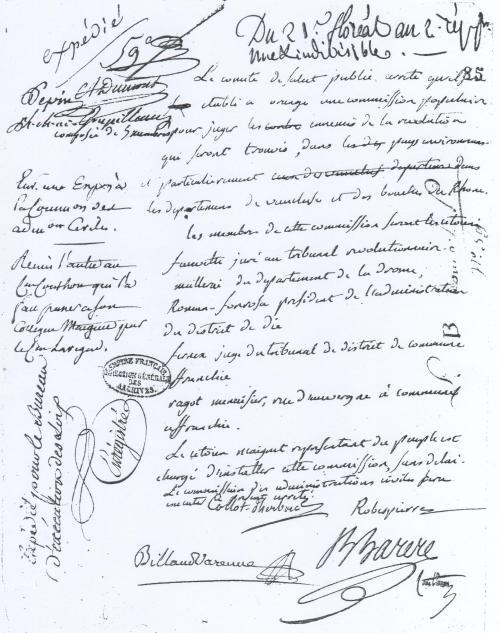

This time, the draft of the decree is in Robespierre’s handwriting (see the image below), and was signed by him, Collot d’Herbois, Couthon, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Carnot. This, together with Robespierre’s undeniable support for the law of 22 prairial, is was has led some historians to want to give him and Couthon equal responsibility for it. There does however exist no real proof for Robespierre being the actual author behind the draft for the law of 22 prairial, nor evidence that he was the mastermind behind the law and just got Couthon to write it, as stated by his enemies after his death (see for example Robespierre peint par lui-même et condamné par ses propres principes… (1794) by Laurent Lecointre).

Today kept at AN, F7 4435, p. 3, pl. 85

When it comes to the involvement of anyone else in the development of the law of 22 prairial, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Collot d’Herbois would in their Réponse des membres des deux anciens comités de salut public et de sûreté générale… (1795) claim that the law had been secretly worked out between Robespierre and Couthon — the rest of the CPS had not only had nothing to do with it, but even protested against it.

Is it not known to all citizens since the sessions of 12 and 13 Fructidor, that the decree of 22 Prairial was the secret work of Robespierre and Couthon, that it never, in defiance of all customs and all rights, was discussed or communicated to the Committee of Public Safety? No, such a draft would never have been passed by the committee had it been brought before it. […] At the morning session of 22 floréal [sic, it clearly means prairial], Billaud-Varennes openly accused Robespierre, as soon as he entered the committee, and reproached him and Couthon for alone having brought to the Convention the abominable decree which frightened the patriots. It is contrary, he said, to all the principles and to the constant progress of the committee to present a draft of a decree without first communicating it to the committee. Robespierre replied coldly that, having trusted each other up to this point in the committee, he had thought he could act alone with Couthon. The members of the committee replied that we have never acted in isolation, especially for serious matters, and that this decree was too important to be passed in this way without the will of the committee. The day when a member of the committee, adds Billaud, allows himself to present a decree to the Convention alone, there is no longer any freedom, but the will of a single person to propose legislation.

Against this be lifted the fact that Barère described the law of 22 prairial as ”a law completely in the favor of the patriots” when it was introduced (in the name of both the CPS and CGS, it might be added) to the Convention on June 10, and that both he and Billaud-Varennes stood on Robespierre’s side when the law was being criticised on June 12 (albeit this time they didn’t strictly speak about the law in itself). Furthermore, Collot d’Herbois, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Carnot, as mentioned above, had actually co-signed the decree for the Commission of Orange on May 10, which suggests that, if they had a problem with the law of 22 prairial, it’s at least unlikely it had to do with the articles it had in common with said decree. All that said, like in the case of Robespierre, there is no solid proof of anyone besides Couthon having worked on the draft.

The historian Léonard Gallois wanted in his Historie de la Convention par elle-même (1835) to give the principal authorship of the law of 22 prairial not to Couthon, but to René-François Dumas, the president of the revolutionary tribunal. This based on the fact that Dumas, according to Gallois, ”didn’t cease to explain to the Committee of Public Safety that it was impossible to legally reach all the enemies of the people and conspirators when these found defenders, allegedly mindful, who held them to ransom, or who insulted revolutionary justice.” On May 30 at the Jacobins, Dumas did indeed suggest ”not to lightly grant unofficial defenders to all those who come to ask for them” and asked ”that a decree stipulating that no unofficial defender may not be granted without the Committee having previously examined the case for which one is requested, be strictly enforced.” Fouquier-Tinville, the public prosecutor, also reported the following in his defence (1795):

On 19 Prairial, I was in the council chamber with Dumas and several jurors. I heard the president speak of a new law which was being prepared and which was to reduce the number of jurors to seven and nine per sitting. That evening I went to the Committee of Public Safety. There I found Robespierre, Billaud, Collot, Barère and Carnot. I told them that the Tribunal having hitherto enjoyed public confidence, this reduction, if it took place, would infallibly cause it to lose it. Robespierre, who was standing in front of the fireplace, answered me with sudden rage, and ended by saying that only aristocrats could talk like that. None of the other members present said a word. So I withdrew. I went to the Committee of General Security, where I was told that they had no knowledge of this work. Two days later, on the 21st, President Dumas spoke again in the council chamber of this new law which was about to be passed, and which would abolish interrogations, written declarations and defenders. That evening again I went to the Committee of Public Safety. There I found Billaud, Collot, Barère, Prieur and Carnot. I informed them of this fact. They told me that it was none of their business, only Robespierre was in charge of this work. They wouldn't tell me more. I went to the Committee of General Security where I found Vadier, Amar, Dubarran, Voulland, Louis du Bas-Rhin, Moses Bayle, Lavicomterie and Elie Lacoste. I showed them my concern. All answered me that such a law was not in the status of being adopted.

While Gallois’ account has not been repeated by other historians (seeing as, again, Couthon’s handwriting is the only one which can be spotted on the draft), it’s also not impossible pressure from people like Dumas inspired the law, especially as he was close to the robespierrists (he is listed on second place on a list of patriots written by Robespierre).

When it comes to the second question — what was the intention with the law? — the historian Annie Jourdan summarized rather neatly the different main theories that have been laid out by historians over the years in a 2016 article titled Les journées de Prairial an II: le tournant de la Révolution ? (which I really recommend for anyone wishing to learn more about all the questions asked here). Franky, I think they all are probably true to some extent, one doesn’t have to exclude the other.

The first interpretation goes that the law was a response to the two failed assassination attemps against Collot d’Herbois and Robespierre on May 22 and 23. These events, the supporters of this theory argue, rattled the Convention in general (who viewed them as part of a bigger, English conspiracy) and Robespierre in particular (see for example this speech he held about it and this letter recalling Saint-Just to Paris written in his hand, both dated May 25 and both rather panicky in tone, as well as a claim made by the deputy Vilate that Robespierre during the last months of his life could speak only of assassination — ”he was frightened his own shadow would assassinate him.”) and this ”law of wrath” to borrow an expression from Hervé Leuwers, was the response, meant to act as the ultimate instrument of defense to protect the regime. What speaks against this being the full truth is the fact that the Orange decree existed already before the assassination attempts, which, as seen, contains much of the same content.

The somewhat opposite interpretation is that the law, instead of a passionate reaction to a sudden event, was a rational response to the Parisian revolutionary justice’s ongoing development. On May 8 1794, a decree had been passed ordering all local revolutionary tribunals (with a few exceptions) be closed and all suspects tried in front of the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris. Naturally, this had caused overcrowding in the prisons of the capital a month later, and a law which speeded up the administration of justice therefore became a servicable solution. A similar line of thought is that the law was one in a series of decrees with the aim of bringing more power for Committee of Public Safety (we already have the law of 14 frimaire (December 4), the decree of 27 germinal (16 April) and the above mentioned decree of 19 floréal (8 May).

The third interpretation is that Robespierre and Couthon wanted to use the law of 22 prairial to be able to lay their hands on Convention deputies they thought needed to be purged. The law contained an article more or less stripping the Convention of its exclusive right to bring its representatives before the Revolutionary Tribunal. This was what said representatives took the biggest issue with, and on June 11,while Couthon and Robespierre were absent, they talked about scrapping it, something that however was undone the next day when the two came back, proving that that article was important to them. Historians especially sympathetic to Robespierre have argued that purging Convention deputies was his only intended purpose with the law (see for example Albert Mathiez who in his Robespierre terroriste (1920) wrote ”It therefore seems quite likely that by passing the law of 22 Prairial, Robespierre only aimed to punish five or six currupt and bloodthirsty proconsuls who had made the Terror the instrument of their crimes.”) But if that’s the case I wonder why Robespierre also personally contributed to making sure people who very clearly were not proconsuls were put under the mercy of the law (the most obvious example being his contribution to the prison conspiracies, where prisoners were brought before the tribunal in big groups to more or less be judged collectively).

A fourth interpretation goes that the reasoning behind the law was neither emotional nor practical, but ideological. Opposing the former interpretation, where it would only have been the question of using the law against only a small number of deputies, this one argues that it was aimed towards all counterrevolutionaries all over France, in an attempt to finally exterminate them all and thus create the ”virtuous republic” Robespierre talks about in his very last speech on 8 thermidor. Against this interpretation can be lifted the fact that Robespierre seemingly protests against the latest bloody developments in the same speech (though while simultaneously asking that revolutionary justice stays the way it currently is…)

Finally, when it comes to what the actual consequences for the law were, it is undeniable that it contributed to what we today call ”the great terror”, that is, the bloody parisian summer of 1794 during which, between the law’s passing on June 10 and the fall of Robespierre on July 27, 1366 people were executed. Exactly how much it is to blame has however been debated. While older historians have wanted to put all the blame almost exclusively on the law, more recent ones have argued that bickering, overlapping and rivalries between different operative bodies made the whole system work badly and that this was the true cause of the bloodletting, and that the law of 22 prairial would not have multiplied the amount of executions had only things around it worked properly.

#law of 22 prairial#robespierre#couthon#georges couthon#maximilien robespierre#frev#french revolution#ask#long post

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

ooh, this reminds me of Prieur de la Côte d’or’s testimony:

[Collot] has been strongly denounced for his conduct in Lyon, after the recapture of that city. But I was witness to the fact that he only accepted this mission with the greatest reluctance, and that Robespierre skillfully employed the strongest solicitations to persuade him to do so, alleging that he alone was capable of combining justice with the necessary firmness, that Couthon had become moved on the scene and cried like a woman; finally a host of reasons to highlight the importance of exemplary punishment against the rebels of this unfortunate city. Révélations sur le Comité de salut public (1830)

Robespierre and Couthon?

this quote from The 12 Who Ruled (pg 157) ….💔 so rude

#robespierre: ugh couthon such a softie#couthon: how about this then: *hands him the law of 22 prairial*

175 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, so um... I don't know if this is considered rude or ignorant (please feel free to yell at me if it is) but I promise I only have good intentions with this.

Okay... I just want to say that it most certainly was not Robespierre's Reign of Terror. The Reign of Terror was more of a group project and Maximilien Robespierre did not have the tyrannical power that Thermidorian propaganda often credits him with having. He was never the leader of France, rather one of twelve members of the Committee of Public Safety. He wasn't bloodthirsty, he actually hated violence and tried to have the death penalty abolished in 1790 (however the National Assembly had already accepted a different proposal a year before for a more humane form of execution, so they went with that instead). He never tried to start a cult around himself. The Festival of the Cult of the Supreme Being was more of his attempt to bring the country together in a celebration of the Revolution and denounce the hardcore atheists who called for the violent abolition of all religion. And he was nicknamed The Incorruptible for a reason, might I just add. He wasn't perfect certainly, what with the Law of 22 Prairial and I'm sure he could have done more for women's rights, but he wasn't a tyrant either. He didn't execute anyone who disagreed with him, rather that's not even how the Committee worked. They could sign arrest warrants, but their prosecution in the Revolutionary Tribunal was out of the jurisdiction of Committee members. Not to mention that Robespierre signed the least number of arrest warrants out of all 12 Committee members. Robespierre was relatively quite a decent person (as was Saint-Just), at least in comparison to say... Collot and Billaud, who were responsible for some of the worst atrocities of the Terror. After Robespierre was executed (without a trial!) by the Thermidorians, they needed to justify killing him, so the Thermidorians began spreading mass propaganda about him and used him as a scapegoat for their own crimes. (Then the White Terror happened).

Also Robespierre had autism and this is a proven fact. There is no way that fruit tart obsessed, 5'3 man didn't have autism.

Anyways, I think I'm done here. Very extremely sorry about all this but I couldn't help myself. I'm just trying to be helpful because a lot of misinformation surrounds Robespierre and it does annoy me whenever I happen across it. If you have any questions, I would be happy to answer them. Regardless, I hope you have a very wonderful day (and again, I am very sorry if this comes off as being rude or indignant).

Oh my gosh thank you so much this is very cool??? Fuck my year 10 history textbook ig 😭😭 I mean I didn't expect nuance from it but I did hope it would at least, well, have some commitment to spreading information (not sure why I expected that) (clearly it didn't)

And don't apologise 😭 I promise you that I am well aware of my lack of awareness (hehe irony) and I love finding out new stuff and this is very very cool <3

I looked it up and here's an article from Britannica if anyone wants more detail :) If you have any other information I'd love to hear it

#history#french revolution#historyblr#robespierre#weirdly specific but ok#asmi#maggots#yay information hehehe

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's always the Law of 22 Prairial this, the Coup of 18 Brumaire that... what about the Birthday of 21 Nivôse an XII (Paul Gavarni)??????

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ultimately my interest and even, I must say, admiration for Robespierre lie in literary roots, not historical ones. I am fascinated by humanness, I am fascinated by the rule of circumstances, I am fascinated by the death of the Ideal, by sublime virtue, by tragedy; I am fascinated, most of all, by the combat against the most base instincts of mankind which finds it cannot fight them without using their weapons, frightens itself, and dies a pitiful death. Nothing can remain pure, ever, but out of virtuous revolutions arise, from blood, undying hopes: that is the pitiful, scanty probity mankind can aspire to. To learn about Robespierre is to weep over our own tragedy but in doing so, expand the boundaries of both mind and empathy.

Basically, Robespierre and the French revolution are my Kantian Sublime, and that is what truly interests me, not only and primarily, say, details on responsibility in the Law of 22 Prairial. So I very much agree when Doyle and Haydon state that "the time may have come when fiction contributes as much to our understanding of him [Robespierre] as the disagreements of historians".

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry for turning your inbox into a french rev discussion but the main reason I do recommend hazan (even though ppl trash him for being biased as if not every historian of the rev is biased to some degree) is because his book does a good job contextualizing and analyzing the context surrounding the french rev events in a way that isn't always included in a lot of books.

a lot of histories of the frev will read like something along the lines of "[x] happened, because [y] happened, and then after that [z] happened." what I like about a people's history is that it takes more of the approach of "[x] happened in a way that was strongly influenced by the public perception of [y] at the time, eventually causing a shift in the cultural paradigm that then led to [z] being devised as a new course of action."

it provides context for a lot of the things that make readers today go 'what the fuck' (marat and the 500 heads, the law of 22 prairial, the fall of the dantonists, etc.) by explaining the differences in the cultural environment of france in the 1790s to the modern world. things that seem weird and off the walls to us now were seen as normal then, and vice versa. it adds that dimension that's often left out of more cut-and-dry histories and allows people to draw conclusions from a wider and more informed point. it's a refreshing technique not often seen in english french rev books (the book itself is translated as the author himself is french) and I don't think hazan having an opinion that sometimes shines through the text makes it less valid of a source, especially seeing as it's pretty easy to disregard if you don't agree with him yourself without making the book unreadable.

Based on the Goodreads reviews, the book does look interesting, especially because I am very curious about what the culture was like at the time. I have it on my list on Goodreads. I don't know how much time I'm going to invest in studying up on the French Revolution, but I certainly appreciate how passionate everyone is on the subject! I think I'm going to set the goal to at least read Twelve Who Ruled, the Tocqueville book about the French Revolution, and then your recommendation, A People's History of the French Revolution. I might listen to the podcast I was recommended first, though. Idk. It might not be as in depth or anything, but I am really clueless here and I just want to start with an easily digestible rundown of everything that happened and then get deeper into it. I really wasn't expecting all this discourse when I asked for recs😅 I'd assumed there would be a generally agreed upon introductory book on the subject. What a fool I was. Anyway, thank you for taking the time to recommend sources for me!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Journey of the Forgotten French Revolutionary Victor Bach: His Opposition to the Directory and Bonaparte, and Questions Surrounding the Mystery of His Death

Le Cœur - La mort de Victor Bach, le 18 brumaire, au pied de la statue de la Liberté, place de la Concorde - P460 - Musée Carnavalet (portrait representing the death of Victor Bach)

Before addressing the hypotheses regarding his mysterious death, it is essential to learn more about the journey of this revolutionary. Here is how he is described in the book Biographie des Contemporains (Biography of Contemporaries), written by Arnault and Jay in 1821: "Doctor in Paris, elector of the department of the Seine in (...) 1798; one of the most enthusiastic and passionate supporters of the Revolution. He was arrested by order of the Directory government and brought before a jury on charges of writing a satirical pamphlet against members of the Directory, particularly those responsible for the law of 22 Floréal, Year VII (May 11, 1799) (...). After being released, Bach continued to vehemently attack the directors and all enemies of the Revolution. In June 1799 (Prairial, Year VII), he delivered a fiery speech at the Jacobin Tribune on Rue du Bac, in which he again railed against the Directory, outlined the dangers threatening the Republic, and proposed the creation of an exclusively democratic government. He concluded his speech by reading a proposed constitution, in which he expanded the notion of democracy so much that the 1793 constitution (...) would have seemed like an aristocratic work by comparison. The revolution of 18 Brumaire, Year VIII, and General Bonaparte's rise to power as Consul, shook his already fragile mind; he took his own life at the foot of the Statue of Liberty."

Historian Bernard Gainot already notes an error in this biography. Victor Bach allegedly gave this speech at the Club du Manège, not at the Jacobin Tribune. Michaud places Bach in the political spectrum of Babouvism or neo-Babouvism, describing him as: "After the fall of Robespierre, he, in turn, was persecuted and narrowly escaped the prosecutions directed at Babeuf's accomplices and the assailants of the Camp of Grenelle." However, Bernard Gainot considers this portrait confused, as it seems to mix up the repression of Year III with the repression targeting the Babouvists from Year IV onward.

This is how Bernard Gainot summarizes this opponent of the Directory: He was born into a family of blacksmiths in Villefranche-de-Rouergue in 1764. His father was a Freemason, and his cousin played a significant local role during the French Revolution. After completing his medical studies, Victor Bach always made sure to mention his medical degree in his signature.

He was deeply committed to the Revolution. According to Gainot, documents from Year III describe him as a former police commissioner of the Chalier section. In his book Les Sans-Culottes Parisiens en l’An II, Soboul cites a denunciation by Victor Bach in Germinal, Year II, against "the wealthy members of his section who had contributed a smaller sum to a collection for saltpeter than the workers of the gunpowder workshop" (as quoted by Bernard Gainot).

Some documents present him as a supporter of Carrier. As a result, the Thermidorian period depicted him as a terrorist, even a Robespierrist (a term as confused as Hébertist, Dantonist, or even Girondin). Under the Directory, Bach remained politically active, living among the neo-Jacobins and continuing to be involved with political opponents of the Directory. He was a member of the Société Politique, where he interacted with well-known revolutionary opponents of the time, including Xavier Audouin, Felix Lepeletier, Antonelle (nicknamed "the Invariable"), Adjutant Jorry, René Vatar, and others.

Victor Bach is far from the unknown figure he is today. The speech he delivered at the Manège in 1799 was well-received within certain circles, but outside, it sparked controversies, such as Poultier’s accusation of Jacobin conspiracy, accusing him of advocating for a revolutionary system based on the suppression of private property. This provided a pretext to close the Manège.

Gainot disputes the idea that Victor Bach represented a split between radicals and opportunists.

Bach invoked the tragedies of the Revolution, not out of nostalgia, but to draw "lessons" intended to strengthen the maturity of the democratic movement. He glorified the "martyrs" of the revolutionary cause, reinforcing a cult of memory typical of revolutionary rhetoric, without necessarily advocating a return to what is sometimes called the troubled period of 1793 (I still have difficulty with the word Terror, knowing that it was coined by opportunists to rehabilitate their political reputations, though I accept it more than the silly term Reign of Terror).

Bach particularly stood out for his emphasis on progressive taxation, which he saw as a key tool for social redistribution and the consolidation of the Republic. This set him apart from other reformers of the time, like Félix Le Peletier, whose proposals, though converging on certain points, lacked the same programmatic coherence. Bach’s program reflected a socially oriented vision, deeply concerned with economic justice, as evidenced by his proposals for public assistance, education, and support for the disadvantaged.

Gainot also highlights that, while Bach aligned himself with the Constitution of Year III, his discourse was perceived as a threat by conservatives. They quickly exploited some of his proposals, particularly the idea of citizens' "co-ownership," to discredit his program by equating it with extreme revolutionary ideas, such as agrarian law or the abolition of private property. However, Gainot demonstrates that Bach was not advocating for the abolition of private property but for extending political rights to a broader segment of citizens. Unlike figures like Babeuf, Momoro, or Jacques Roux ( Jacques Roux who encroached on property during food store pillages), Bach was one of those republicans who believed in the sanctity of property rights.

In a broader perspective, Gainot connects Bach to other republican figures of the time, such as Bernard Metge (a staunch opponent of Sieyes and Bonaparte, as well as an adamant adversary of Babouvism) and François Dubreuil, who shared similar concerns about pauperism and the defense of republican principles. However, these militants, though active in the democratic opposition, were unprepared for the repression that followed under the Consulate, leading to their marginalization or political disappearance.

The article shows that Bach’s trajectory, and that of the neo-Jacobins in general, is emblematic of the tensions between pursuing revolutionary ideals and the reality of a republican regime in transition, seeking to stabilize while fighting internal and external threats. Bach, though aware of the dangers, seemed to believe in the continued existence of an open public sphere where democratic debates could still take place.

I appreciated Bernard Gainot's comparison of the similarities and differences between Victor Bach and Felix Le Peletier. Both were fervent republicans who sought to regenerate the Republic and combat corruption, particularly by defending the principle that civil servants should be held accountable, transparently revealing their income, for example. Both believed in the right of association, albeit for different reasons—one to defend political freedoms, the other to maintain contact with the people, who would be a key element in the struggle.

They sought to punish traitors and embezzlers and defended a social-economic program. But Victor Bach was more radical than Felix Le Peletier. He placed even greater emphasis on proposals such as progressive taxation and assistance to the poor, whereas Felix Le Peletier, though he mentioned these issues in his speeches, was more cautious, likely out of tactical prudence given that they were a minority facing the Directory.

Bach aimed his message more at the neo-Jacobins who would recognize themselves in his discourse, while Felix Le Peletier sought to appeal to a broader audience, including republican notables or part of the Legislative Body.

Now we turn to the circumstances of Victor Bach's death. Traditionally, he is seen as a republican who, upon witnessing all his fears materialize in the form of a military dictator and the destruction of the Revolution, killed himself with a pistol on 18 Brumaire at the foot of the Statue of Liberty when Bonaparte took power. However, this theory is challenged by several pieces of evidence. At that time, the press was not yet fully censored, and if a well-known figure like Victor Bach had committed suicide under such conditions, it would have been reported in the press at least. A man did indeed commit suicide on 3 Frimaire, Year VIII (November 24, 1799), but this man was named Carré and did so at the foot of the Statue of Liberty.

So, what happened to Victor Bach? Bonaparte had not forgotten him, as we know he used the machine infernale incident perpetrated by royalists as an opportunity to eliminate opposition from the left, sending some people he knew well (notably Giuseppe Ceracchi, tortured for false confessions and sent to the guillotine, among others) to their deaths.

Bach was listed for deportation, yet his name was later altered with the claim that he had committed suicide on June 5, 1800, in the Bois de Boulogne. However, this body turned out to be that of a certain Arson. So, what happened? What are the exact circumstances of Victor Bach's death?

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the Bois de Boulogne was a known location for duels. Gainot puts forward three hypotheses: Le Journal des Hommes libres reports that during the period of Year VIII, disputes escalated into duels, with one side consisting of democratic supporters and the other of those aligned with Sieyès. Victor Bach, being an opponent of Bonaparte, may have been involved in such a duel and died as a result. His body could not be identified, even though it was said that he died in the Bois de Boulogne.

However, there is another, more troubling hypothesis raised by Gainot: it is possible that an agent (perhaps acting under Fouché’s orders) secretly eliminated Victor Bach to rid themselves of a troublesome and well-known political adversary. This is plausible, as Bonaparte (or his advisors like Cambacérès, Fouché, Talleyrand) broke many legal norms. The fact that no evidence has surfaced could support the idea of the destruction of compromising documents. Given Bonaparte's history of eliminating bodies, as seen with the former slaves, rebels, and even innocent Black individuals drowned by Rochambeau and Leclerc under Bonaparte’s orders, one might wonder if such methods were employed against Bach. But in 1800, in metropolitan France, why would they do this to Bach and not extend the same treatment to other Bonaparte opponents like Buonarroti? And what would Bonaparte (or Fouché, Talleyrand, or Cambacérès) gain from such an action? Moreover, the surprise surrounding Bach's death seems genuine, as he had been on the deportation list, and it was only when his death was learned that a modification had to be made.

The third hypothesis is that of suicide. It is suggested that Bach might have taken his own life after Bonaparte’s victory at the Battle of Marengo (June 1800), which solidified the latter’s power and dashed the hopes of the republican opposition. However, his body mysteriously disappeared, leading to speculation that his friends may have discreetly buried him, or that the police erased all traces of his death. On the other hand, Victor Bach comes across as a fighter, an authentic revolutionary who did not waver even during the harshest periods of the Directory. But this hypothesis remains more plausible than the second. Personally, I lean toward the first hypothesis, but if that were the case, why was his body never found for identification, especially since he had family he was constantly in contact with, as well as colleagues nearby? Why didn’t they reported his death? I understand the part where they might have wanted to bury him in secret to ensure his body was treated with respect, but not to mention it at all seems odd. This whole affair is quite mysterious.

In any case, it seems safe to say that he died before the roundup of Jacobins for deportation or execution, and that’s likely the only certainty we will have. However, we can still remember his revolutionary work, both for the good he accomplished and for what he may be criticized for. We should strive to bring him out of the obscurity into which he has fallen, considering that he was well-known during his lifetime.

I end with some extracts from Victor Bach's speech qu'il a adressé au Directoire.

"… calculate, if you can, the sum of the vices, the crimes, and the evils of all kinds that have emerged from the cavern of the overthrown Directory, like another Pandora's box; count, if you can, the number of families they have plunged into misery, divided, decimated, or annihilated; measure, if possible, the tears and blood they have caused to be shed! The blood of several million men, the tears of almost all the peoples of both hemispheres, condensed on their sacrilegious heads, form a black, dark, thick cloud, from which the thunder will inevitably strike to crush them sooner or later. Illustrious spirits of the victims of Vendôme, sacrificed by Viellard on the altar of the bloodthirsty gods who desecrated Luxembourg! Revered spirits of the overly trusting republicans massacred at Grenelle, no less precious spirits of the democrats of Switzerland and Italy! And you, generous and immortal spirits of our heroes, reduced to every kind of deprivation, and sacrificed in the hospices and in battle to satisfy their insatiable thirst for blood and riches, who undoubtedly delight in soaring over this cradle of liberty—take back for a moment your bloodied bodies, gather your scattered limbs, rise from your graves, stand up, and come with us, with your mutilated comrades, with your widows and orphans, your fathers, mothers, sisters, and mourning brothers! Come, come demand with us from the Legislative Body full justice and swift vengeance!" ( I think that it is Victor Bach who make this speech)

Those are definitely from him: When he warns against impulsiveness: "It is certainly good and useful to have confidence in one's abilities and resources; but this commendable presumption, without which one cannot hope for victory in battle or in politics, has its limits. If these limits are exceeded, it becomes nothing more than recklessness, powerless bravado, a ridiculous boastfulness that turns the laurels, which one was certain to win, into cypress, had one only listened to the humble voice of wisdom and prudence…"

When he addresses the members of the Directory by name: "Yes, guilty as you may be, Reubell, Merlin, and all of you legislators, directors, or ministers who may be their accomplices! I do not wish for your death, but rather that you be sentenced to sweep the streets of Paris, dressed in those grand costumes that gave you the pride, greed, and cruelty of the kings you sought to imitate."

Rest in peace Victor Bach.

Sources: Albert Soboul Biographie des Contemporains (1821) by Arnault and Jay Michaud Journal des Hommes libres Bernard Gainot’s investigation into the "suicide" of Victor Bach, extracted from Annales historiques de la Révolution française

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Robespierre support the 22nd Prairial law? wasn't that reckless, given that it compromised his own immunity? Do we know what the thinking behind that was? it's weird to me that he'd support something so clearly unpopular and which ALSO put him in personal danger

OK, full disclosure: I am not that knowledgeable about the Prairial law, so I don't know details on what was going on in the background. (I am not even sure anyone knows?) We know that the law was written by Couthon, and it is assumed that Robespierre not only supported it but encouraged it (if not co-written it). However, I am not sure how solid those sources are.

This post goes into more detail about this mess: https://anotherhumaninthisworld.tumblr.com/post/726620864864452608/what-is-the-whole-story-of-the-law-of-22-prairial

We know that everyone tried to wash their hands off the Prairial law after Thermidor, and the legacy of it became "Robespierre's murderous attempt to murder everyone", but while I do think Robespierre supported the law, I don't know who else supported it (future Thermidorians, too?) or what was the intended purpose of it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who lies more: Charlotte, Fouché or Barère?

Frankly I know way too little about both Fouché and Barère to be able to say something really concreate about how much they lie (@tierseta @kocokoala anyone? would you mind adding what you know?) All I really have is that what Barère wrote in his memoirs regarding the way Collot d’Herbois returned from Lyon does not seem to line up with what better, more contemporary sources have to say. In Réponse des membres des deux anciens comités de salut public et de sûreté générale… (1795) Barère, Collot and Billaud-Varennes also claim that the law of 22 prairial had been worked out in secret between Couthon and Robespierre, while the rest of the CPS had had nothing to do with and even protested against it. Only on June 10 1794, when the law was introduced to the Convention, Barère is recorded to have called it ”a law completely in favour of the patriots.”

For Charlotte, I know of the following things, which all originate from her memoirs:

Charlotte writes that before the revolution her older brother gave up his functions as a judge after having had to sentence a man to death. But according to Robespierre (2014) by Herve Leuwers, he actually never resigned from this position.

When writing about having dated Fouché, Charlotte claims this happened during the revolution, which can hardly be accurate given the fact Fouché was already married by then.

Charlotte declares a letter written by her to Augustin dated July 6 1794 had had apocryphal parts inserted into it when it got published after their death. In an inserted footnote, Laponneraye writes that”this letter […], I am convinced, was for Charlotte Robespierre an object of constant torment; the idea that someone could have thought she could have written it the way it is, and that it had really been adressed to Maximilien Robespierre, tantalized her. All the times I saw her, she spoke to me about it. One day we read it together, and I asked her to indicate which passages she hadn’t written and where infamous falsifications had been added; I publish this version in the Pièces justificatives section.”However, an encounter with the fac-simile shows that no alterations has been made to the letter, which is entirely in Charlotte’s hand.

When describing her arrest right after thermidor, Charlotte writes that she, after having been insulted and struck by guards at the Conciergerie on 10 thermidor for begging to see her brothers and been led away by some people moved to pity, she completely loses her reason and doesn’t come back to herself until a few days later, finding herself in prison with a woman who, after yet another few days, convinces her to sign a letter she has written, the content of which Charlotte doesn’t look at (and if even real, has never been found). The letter is sent off, and the next day both are set free. A story which doesn’t line up completely with what official documents tell us about Charlotte’s arrest, which according to them took place on 13 thermidor. An interrogation of Charlotte was held the very same day, in which she disowns both her brothers and the Duplays, denounces a man named Didier and claims she had almost been the victim of the Revolutionary Tribunal. For some reason or another she also gave her age as 28 when interrogated, which is obviously false… The circumstances regarding Charlotte’s release from prison are however dubious here as well, as no order for it appears to exist…

Charlotte claims to have been witnessed meetings both Marat and Pétion had with her older brother. But in both cases, the meetings she alludes to appear to have played out before she even came to Paris in late September 1792…

She also writes that her brother went to visit Desmoulins in prison once he ”learned of” his arrest, but that the latter didn’t want to see him, something which I found unlikely given the fact Robespierre had both already signed Desmoulins’ arrest and prepared his indictment, while Desmoulins in a prison letter to his wife reveals that he is writing to Robespierre, meaning he shouldn’t have repulsed him was he to come visit.

Like I have already written here, I also doubt Charlotte actually tells the whole truth regarding the things she was up to during the revolution and what it was that caused a split between her and her brothers, even if the things she does say about them do not have to entirely dismissed.

It wouldn’t surprise me if Barère and Fouché lie about more/more serious things compared to Charlotte. Though I guess the reveal of fabrications/alterations in her memoirs is still more surprising given the fact Fouché and Barère didn’t really have the reputation of being honest men/reliable narrators to begin with… Then there’s of course also a discussion to be had regarding how much of what they’ve written that is blatant lies and what is simply a partial telling/personal conception of the full truth or honest misremembering.

#charlotte robespierre#bertrand barère#joseph fouché#ask#frev#french revolution#lies lies and more lies

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robespierre: Georges come over

Couthon: I can’t

Robespierre: I’m depriving traitors the aid of counsel and witnesses for their defense

Couthon:

#french revolution#france#frev#robespierre#danton#reign of terror#french#history#marie antoinette#desmoulins#maximilien robespierre#georges couthon#terror#Law of 22 Prairial#loi de la Grande Terreur#la terreur

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

From this law [the law of 22 Prairial], too, sprang the “Great Terror” which, in Paris, accounted for nearly 1,300 of the guillotine’s 2,600 victims.

George Rudé, Revolutionary Europe 1783-1815

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think you're confusing the actual text of this post with what you think people are saying about major social change/revolution in general.

This post is specifically about the fantasy of a Glorious Violent Revolution. The noble and "righteous" Guillotine revolution. This isn't about the concept of revolution in general. This isn't about denying the current status quo is violent. It's also not stating that what exists now is immutable, unchangeable, or human nature. It's not a defense of capitalism.

It's a criticism of bloodthirsty violent fantasy (and imo that fantasy IN LIEU OF genuine reform, revolution, or social change). It's a criticism of the spectacular and bloody imaginings that get glorified because people are idiots who only care about the Guillotine Killing The Rich Like The Glorious French Revolution and don't bother to consider small details like The September Massacres, The Terror, the White Terror, how many people in the National Convention were executed, imprisoned, or committed suicide, or the fact that one of their most well known leaders was also ultimately executed. y'know — basically the thousands of people who died and weren't the aristocracy but instead also revolutionaries, or non-political prisoners, or anyone "suspicious," per the Law of 22 Prairial.

The big fantasy of the guillotine is about feeding an impulse for violent, gladiatorial drama for the masses, it's a fantasy that speaks to people whose grasp of the reality of a "revolution" is basically the just theatrical release of Les Mis.

It's not a criticism of the idea that we should demand and agitate for large-scale and necessary change. This seems fairly obvious.

“LOL. You think your vote matters? ROFL and LOL.” Yes, I am aware my vote carries less and less relative power the more people I’m voting with, but unlike your glorious violent revolution, it actually exists.

#i used to find guillotine jokes amusing and nonserious but now im convinced#people just talk about the guillotine revolution because a) they have nothing of substance to contribute to meaningful change#and b) theyre completely ignorant of the history of the most infamous guillotine revolution being a massive shitshow#people want blood and spectacle and i frankly can't trust this wouldn't end up different from public lynchings#just because it's not The State or the Ultra-Rich killing people doesnt make mass executions Good#ive literally got multiple ancestors who fought in multiple different national revolutions#one of them was alive in my grandparent's living memory#but like i doubt they treated The Revolution like it was some kind of magnificent game

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been so absorbed into the history of french revolution lately, and I grew to love and empathise with Robespierre more than I thought. But sources about him are so contradicting or lacking that a newbie of history like me hard to tell what is true.

Did he propose for or against execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoniette? Some said he thought let the treacherous king live brings danger to the republic, other said he against the death penalty but got rejected@_@

Did he and Couthon reenact the Law of 22 Prairial, which tripped off one right for a fair trial before execution, 2 days after the festival of Supreme Being? If so then why did he do that, so odd of his character and policy? Was it out of desperation to get his enemies condemned quickly, or was it out of physical illness and mental exhaustion, or both?

Also what exactly happened between him and Desmoulins and Danton? Im so confused of why the Convention executed them@@

I would hugely appreciate to be enlightened in these matters. ☺️

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello citizen do you know what was the real point of the law of Paririal? It seems so out of character for Couthon (who was very soft with repression when he was in Lyon) and Robespierre (who was so appaled by bloodshed) to draft and support it.

Dear Citizen Anon, I am so sorry for my late reply! In part, it was because of a busy schedule, but tbh, also because I did not know how to answer this. The truth is: I don't understand the Prairial law. Like, at all.

I mean, I understand its basics, but not what they thought they'd achieve with it. It is baffling to me in many ways. And not just in ethical terms; I mean it in purely logical sense.

I do think I can (partially) answer why Couthon, though: SJ was in the army. Though I also think SJ was involved in this mess, because he was in Paris at one point, just not when it was presented.

I am sorry I cannot give a better answer; I will try to gather more info and discuss it. In the meantime, here is an article I found on the subject. I am still to read it in full, but looks like it might answer some questions:

If someone can explain this in more detail, please share! I am always looking for more info on the Prairial law.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

context for earlier tags. thomas paine, defending his fellow prisoner from accusations of spying for robespierre post-thermidor:

We found ourselves in entire agreement in the horror which we felt for the character of Robespierre, and in the opinion which we formed of his hypocrisy, particularly on the occasion of his harangue on the Supreme Being, and on the atrocious perfidy which he showed in proposing the bloody law of the 22 Prairial [June 10, 1794]; and we communicated our opinions to each other in writing, and these confidential notes we wrote in English to prevent the risk of our being understood by the prisoners, and for our own safety we threw them into the fire as soon as read.

quoted from MD Conways collection which is ancient but online for free here: https://books.google.com/books?id=wZ8rAQAAMAAJ&pg=PR15#v=onepage&q&f=false

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

In your last reply you mentioned that knowing exaclty which deputies Robespierre was referring to in his speech is a question for another day. I take the opportunity to ask it to you now! Are there some primary sources stating the exact names and if not who do you personally think they were? I initially thought he was referring to the deputies on missions that committed many atrocities, but this post of yours ("Robespierre — ”horrified” by excessive Representatives on Mission?")made me skeptical about it.

Nope, no complete list of name was ever found, so figuring out exactly who Robespierre was gunning for is entirely up to speculation. Personally, I think the best way to do it would be looking over several pieces dating back to the months/weeks surrounding thermidor, and the more places a person’s name shows up on, the more likely they are to have been on the menu.

We can start off with Robespierre’s 8 thermidor speech and the people that he does mention by name in it. This gives us above all Cambon, Ramel and Mallarmé:

The counter-revolution lies in the administration of finances. It is all about system of counter-revolutionary innovation, disguised under the appearance of patriotism. It seeks to foment agiotage, to weaken the public credence by dishonouring the French loyalty, to favour the rich creditors, to ruin and to discourage the poor, to multiply the number of unhappy ones, to deprive the people of the national goods, and to imperceptibly bring the ruin of the public fortune. Who are the supreme administrators of our finances? Brissotins, Feuillants, aristocrats and known rascals. Who are the supreme administrators of our finances? Brissotins, Feuillants, aristocrats and known rascals; these are the Cambons, the Mallarmés, the Ramels; these are the companions and the successors of Chabot, of Fabre and of Julien de Toulouse.

In a struck out part he also openly denounces Amar and Jagot from the Committee of General Security:

Amar and Jagot, having seized the policing, have more influence alone than all the members of the Committee of General Security: their power is still based on this army of clerks of which they are the bosses and the generals; it is they who are the principal architects of the system of divisiveness and slander.

Finally, in one version given of the speech he also explicitly denounces Fouché for his role in the dechristnanization process — ”No Fouché, death is no eternal sleep.”

Other than that, no names are mentioned, but we do learn about other elements regarding the conspiracy — its members have sought to ruin the revolution through excess on one side and indulgence on the other, some of them are advocates of atheism, and all of it can be traced back to British Prime minister William Pitt, the duke of York and ”all the tyrants that are armed against us.” More importantly, it includes deputies of both the Convention, the Committee of Public Safety (CPS), the Committee of General Security (CGS) and agents of this latter committee. For the CPS, Billaud-Varennes is indirectly denounced: ”Why do those who told you once : I tell you that we are walking on volcanoes, believe that they only walk on roses today?” This is confirmed by the speech Saint-Just tried to hold the following day — ”Billaud often repeats these words with feigned fear: We are walking on a volcano.” The CGS is in its turn distincly denounced for the so called Catherine Théot affair (which I wrote about more at length here). While again no specific names are mentioned, the committee member most implicated in said affair was its president, Vadier, who was the one who read aloud the report regarding it to the Convention on June 15.

Second of all, we can take a look at these notes on ”suspect” deputies found among Robespierre’s papers, written by him sometime after the passing of the law of 22 prairial. On the list is Dubois-de-Crancé, held suspect for behaving like a counter-revolutionary while on mission and having been closely linked with the Duke of Orléans, Delmas, suspect for being a former noble and a ”mad intriguer”, behaving ambiguously at the army of the North and having been allied with the Girondins and then the dantonists, Thuriot, for being an ally of Orléans, having quited down after the death of Danton, going to dinners held by the latter and Delacroix and while there having made ”an attempt to stop the revolutionary movement, by preaching indulgence under the name of morality, when one delivered the first blows to the aristocracy” and trying to arm the National Convention against the CPS when Saint-Just read out the report against the dantonists, Bourdon de l'Oise for throwing orgies and killing voluntaries with his hand while on a mission, making a motion to no longer pay direct taxes which would remove the resource of fish, speaking out against the law of 22 Prairial when it was first introduced, being a fierce defender of the system of atheism and dismantling the decree proclaiming the existence of the Supreme Being, making sarcastic remarks during the festival of the Supreme Being, threatning a young girl with a pair of pistols and saying that, if he were to shoot himself, she would be accused of murder and guillotined, having written a letter to counter-revolutionary saying that the prisoners would soon be released and those responsible for their arrest put in their place, and walking ”with the appearance of an assassin who contemplates a crime,” and finally Léonard Bourdon, suspect for having been a ”despised intriguer all the time,” one of the principal accomplices of Hébert and Cloots, composing a counter-revolutionary, hébertist, opera that was shut down by the Committee of Public Safety, enlarging the number of his lodgers, trying to solicit the liberty of a Dutch banker and then denying it, as well as speaking without taking his hat off and wearing ridicolous clothes at the Convention.

This list also implicates Carnot, who brought a clerk Bourdon d’Oise presented into his offices (a clerk that was later dismissed upon the repeated proposal of Robespierre) and is often communitating with Delmas, as well as Dufourny, denounced as a friend of both Danton and Dubois de Crancé.

Third, we can look at the people Robespierre openly denounced in the weeks right before thermidor. Here we find Pille, denounced by Robespierre on July 16, saying that his conduct ”deserves the most serious attention,” Fouché, expelled from the Jacobins by Robespierre on July 14 for his conduct while on mission and having since become ”the leader of the conspiracy which we have to thwart,” Dubois-Crancé on July 11, accused of showing weakness in the taking of Lyon by Robespierre and expelled from the Jacobins on the initiative of Couthon, and Tallien on June 12 who Robespierre claims ”is one of those who speak incessantly with terror, and publicly of the guillotine, as something that concerns them, to debase and disturb the National Convention.”

If we back a few more months we find Amar, called out on March 16 for his report on the East India company scandal by Robespierre and Billaud-Varennes, who both consider it too narrow. The same day Robespierre also openly opposes a motion from Léonard Bourdon, who, he says, ”it is not yet proven doesn’t belong to the conjuration,” and finally, on April 5 Dufourny is expelled from the Jacobins by Robespierre as a friend of Danton.

We also have an unfinished, undelivered speech Robespierre wrote somewhere in February-March 1794, before the purge of the hébertist and dantonists. Among the by now executed men, we also find a few that have escaped procecution:

And who are the authors of this system of disorganization? […] It’s Dubois-de-Crancé, accused of having betrayed the interests of the Republic before Lyon. It’s Merlin (de Thionville), famous for the capitulation of Mayence, more than suspected of having received the prize; It’s Bourdon de l'Oise; it’s Philippeaux; it’s the two Goupilleaus (Jean-François Goupilleau and Philippe-Charles-Aimé Goupilleau) both citizens of the Vendée; all needing to throw back on the patriots who hold the reins of the government the multiplied prevarications of which they were guilty during their mission of the Vendée; It is Maribon-Montant, once a minion and declared partisan of the former Duke of Orléans, the only one of his family who has not emigrated, formerly as proud of his title of marquis and his financial nobility as he is now bold to deny them; serving as well as he could his friends at Coblenz in the popular societies, where he recently condemned to the guillotine five hundred members of the National Convention; seeking to avenge his humiliated caste by his eternal denunciations against the Committee of Public Safety and against all patriots.

It can finally also be observed that in his notes jotted down against the dantonists, Robespierre writes that Danton’s influence can be spotted in the writings of Bourdon (he doesn’t specify which one). Robespierre’s ally Claude-François Payan (put on third place on a list of patriots written by Robespierre) did in his turn call for the overthrow of ”Bourdon and his accomplices” in a letter to Robespierre dated June-July 1794.

We can also look at which deputies Robespierre’s collegues after thermidor said he wanted proscribed. These pieces should of course be treated with more caution given the time they were written, but they do still come from people who would have been in the right place to know and most were reported not that long after the fact.

The deputy Joachim Vilate reports in his Causes secrètes de la révolution du 9 au 10 thermidor (published October 1794) to have talked to Barère right after Robespierre had read his speech on 8 thermidor. The conversation, he claims, went as follows:

After a few minutes of silence I asked [Barère] this: ”Who might [Robespierre] have reason to attack?” ”This Robespierre is insatiable,” said Barère, ”since we won’t do everything he wants, he must break the glass with us. Had we been talking about Thuriot, Guffroy, Rovère, Lecointre, Panis, Cambon and this Monestier, who has offended my entire family, and the whole aftermath of the dantonists, and we would also understand him asking for Tallien, Bourdon de l’Oise, Legendre, Fréron, in due time…, but Duval, but Audouin, but Léonard Bourdon, Vadier, Vouland, it is impossible to consent to that.”

Barère himself, along with Billaud-Varennes, Collot d’Herbois and Vadier, reported the following when defending themselves against Laurent Lecointre’s charge of having been Robespierre’s ”accomplices” in 1795:

They are strange accomplices of Robespierre, those who, against his will, made a political report on the religious troubles, sheltered from all research in this matter the representatives of the people sent on mission in the departments, defended Tallien, Dubois-Crance, Fouché, Bourdon de l'Oise, and other representatives whom he relentlessly pursued. […] One day, we read letters and information sent to the Committee of General Security: Robespierre demanded immediate arrest for the two deputies denounced in these letters: the arrest of Dubois-Crancé was discussed and rejected: that of Alquier was strongly advocated by Robespierre who accused us of softening against the culprits and thus losing the public sake.

They also share an anecdote where Carnot would have called Saint-Just and Robespierre ”ridiculous dictators” during a committee meeting in May-June, after Saint-Just had threatened him with the guillotine. This incident is probably what Robespierre is referring to when he on July 1 said: ”In London I am denounced as a dictator, the same slander has been repeated in Paris: you would tremble if I told you where.”

They also write that during a CPS meeting on June 11, its members, with Billaud-Varennes in the forefont, loudly accused Couthon and Robespierre of having written and pushed through the Law of 22 Prarial without anyone else in the committee having been involved, and that the session after that got so stormy that the windows had to be closed.

In his memoirs, however sketchy those may be, Barère also claimed to have remember Robespierre showing a list to the CPS. ”It contained the names of 18 deputies [Robespierre] wanted to indict for going beyond their merit and exercising tyranny in the departments to which they had been sent. I remember a few of these names: Tallien, Fréron, Barras, Alquier, Dubois-Crancé, Monestier du Puy-de-Dôme, Prieur, Cavaignac.”

As for the representatives on mission, I think it’s rather clear Fouché was among the people Robespierre was after (you don’t exactly get called ”the leader of the conspiracy” for nothing). And as can also be seen, Fréron and Barras they too appear, if not in Robespierre’s own papers and speeches, at least on lists given after the fact by people who worked close to him. However, if it can be established that Robespierre possibly targeted these three, I don’t think it can be pinned down that he did so precisely for the excessive violence they exercised in the departments as the story often goes. Like I wrote in the post you cited, judging by what Robespierre says to Fouché when denouncing him, I think it sounds more like he’s accusing him of dechristnanization and falling out with Lyon’s local jacobins than he is of executing too many people (on July 11 he does after all say that national justice in Lyon ”wasn’t executed with the degree needed. The temporary commission initially showed energy, but soon gave way to human weakness which too soon tires of serving the fatherland.”)

For Carrier, I can find absolutly no mention of him in either Robespierre’s speeches and papers or lists given after the fact. The only person pointing him out as someone Robespierre had a problem with that I know of is Charlotte Robespierre in her memoirs — ”Many times [Maximilien] asked, in vain, for Carrier, whom Billaud-Varennes protected, to be recalled.” Charlotte already makes other claims regarding her brother’s supposed moderation that get more dubious when you look closer at them, and in this case we even have a different statement to counter it with. It comes from the deputy Laignelot who during the trial of Carrier had the following to say:

Before Carrier was denounced, I had told this fact to several of my colleagues. I went to see Robespierre; I described to him all the horrors that had been committed in Nantes; he replied: “Carrier is a patriot; that was needed in Nantes.”

Judging by when Laignelot says this, it can’t exactly be treated as hard evidence either, but I think it is enough to get Charlotte’s claim locked in a word against word duel. It must on the other hand be observed that all the lists from right after thermidor were written after Carrier had been either arrested or executed, and that it therefore doesn’t sound impossible the author would have cleaned up his name would it be true he was on there, but then there’s no way to prove that was the case either.

I will say I think you can still build a functioning thesis that Robespierre was aiming at the representatives on mission, and this for having been too excessive with the amount of executions. However, with so many others deputies explicately named by Robespierre himself, I find it hard to believe they were the prime targets, which is why it’s so strange to me that some historians still portray it that way.

Given the things written above, my own guess as to which deputies Robespierre was targeting would go a little like this:

Likely on the list: Cambon, Ramel, Mallarmé, Amar, Jagot (openly denounced in Robespierre’s thermidor speech), Bourdon de l’Oise (brought up 6 times) Dubois-Crancé (5 times), Fouché (3 times), Léonard Bourdon (3 times) Delmas, Thuriot (appear on a list of suspect deputies).

Possibly on the list: Tallien (3 times), Fréron, Alquier, Monestier, Billaud-Varennes, Vadier, Carnot (2 times), Barras, Pille Merlin de Thionville, Jean-François Goupilleau, Philippe-Charles-Aimé Goupilleau, Maribon-Montant, Thuriot, Guffroy, Rovère, Lecointre, Panis, Duval, Audouin, Vouland, Prieur, Cavaignac (1 time).

60 notes

·

View notes